Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Third Editions

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

That was the only target set for those 20 or so young, ambitious, hilarious and unkempt creators.

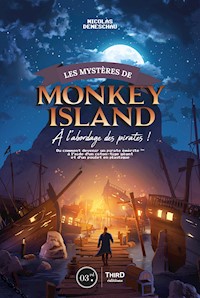

Lucasfilm Games™, soon to be LucasArts™, would become a legendary developer, not least because it was within its walls that The Secret of Monkey Island™ was created in 1990. The best-known of the Point & Click adventure games, Monkey Island earned its reputation from its world of colorful, delightfully anachronistic pirates, its trademark Monty Python-style humor, and, quite simply, the fact that it revolutionized a genre. This book is an homage to the adventures of Guybrush Threepwood™, pirate extraordinaire. But it also aspires—quite ambitiously—to explain why Monkey Island marks a pivotal milestone in the way stories are told through video games. It’s also an opportunity to look back at the tumultuous history of LucasArts and Telltale Games, to discover some voodoo grog recipes, to learn interactive pirate reggae songs, to impress at a party of 40-year-old geeks, and to discover one-liners as sharp as a cutlass (great for duels and birthdays).

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 595

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover

Title page

This book is dedicated to all those who are still, to this day, enthralled by a bunch of pixels.

To Bret Barrett and Martin “Bucky” Cameron. To Stan, who suffered the collateral damage of a corrupt system.

Foreword

Monkey Island Meanderings

A little more than 20 years ago I was offered the chance to co-direct the next Monkey Island game with Jonathan Ackley. The series felt like the heart of LucasArts, the big personality of the studio, the crazy thing that everyone points to when asked, “What are you guys all about?” When I started at the company, I was still getting used to the idea of getting paid to make art and probably would have been happy painting George Lucas’ house. The last computer game I’d played featured ASCII characters as protagonists,1 so seeing cartoons I could control in The Secret of Monkey Island was a revelation. I went on to work as an animator on Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge, then finally got my chance to dream up Guybrush’s next adventure in The Curse of Monkey Island.

It felt a bit surreal, like your parents handing you the keys to their Mercedes and saying, “Now, be careful with this. It’s really valuable, and everyone will be looking at you. But we trust you.” We were momentarily intimidated. “What if it’s too much for us? On the other hand, it’s just been sitting there… Someone should be using it.” Of course, after our initial concept pitch, management said, “What were you thinking?! Maybe you aren’t ready for something this nice.” And we may have been grounded for a while, but eventually we got things all patched up and… now I’m realizing I really should have used a pirate analogy here.

We knew we had inherited this amazing franchise, but the challenge was trying to figure out where to take it next. Creator Ron Gilbert and writer Dave Grossman were no longer with the company, so we couldn’t pick their brains. Writer Tim Schafer certainly gave us some fun suggestions and encouragement, but didn’t have any big Monkey Island secrets to spill. It’s possible he never knew Ron’s big plan for the series in the first place. Or maybe he just kept it to himself thinking that was Ron’s direction and we should find our own.

So, we had to do a little detective work and a bit of winging it. Luckily, we had a good treasure map in the first two games to point the way (there we go, back on track with a pirate analogy!). Those games were rich in characters, locations, puzzles, and humor and told us most of what we needed to know. Sure, there may be details some fans will argue about (I’ve heard Ron said that Elaine would never marry Guybrush), but then the world of Monkey Island can be full of surprises. And part of the surprise is where the monkey muse will take each game’s creator.

Everybody thinks they know Guybrush, but he seems to evolve in interesting ways with each outing. He’s a loveable universal avatar, the put-upon everyman pirate who’s a little too plucky for his own good, always ready with a sarcastic quip when his enthusiastic naivete walks him to the edge of the plank. Plus, he’s got really deep pockets. He’s a character with a voice all his own (although often provided by actor Dominic Armato), one that takes over when you write and design for him. You just can’t help but channel cartoon pirates when you work on the Monkey Island franchise.

Those animated scalawags drive the jokes, inspiring sea shanties and insults, wayward musings of priceless jewels. When we were working on the proposal scene in The Curse of Monkey Island, I was simultaneously shopping for an engagement ring for my soon-to-be wife. Sometimes I wondered whether it was me or the game at the helm. Thankfully, that ring wasn’t cursed. Although, now that I think of it, my wife and I both lost our rings a while back. We’re just waiting on some buried treasure, a rediscovered old royalty check, or a high-paying offer to make The Curse of Monkey Island: Remastered in order to replace them.

Plus, gamers like being Guybrush. They want to swashbuckle with him (although there was technically never a “swash” verb in the interface of the first two games). They like making him poke the surly pirate, deliver the witty comeback, and try to use strange inventory items together. He’s someone they can relate to and express themselves through. It’s the same with those of us who’ve worked on the series. I have no idea what Ron intended for Monkey Island 3 (although I’d love to see it someday), but I do know that the early pitch for The Secret of Monkey Island had a different tone than the final game. And I even heard tell around the office poop deck that Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman just wrote a bunch of silly jokes as placeholders while wiring up the game functionality, but Ron liked it so much he told them to keep at it. That may not actually be what happened, but since it’s now in a book, it’s part of history. Also, while I’m at it, all the good ideas in The Curse of Monkey Island were mine.

The series has actually evolved significantly to reflect the perspectives of all the people who worked on it. The franchise that Ron created and generously shared with others has turned into a vessel of crazy rogues, from the hapless hero, the heroine who’s out of his league, and the constantly transforming villain to an ever-expanding cast of supporting characters whose very concept elicits laughs. In what other world could a throwaway line from an undead skull inspire a recurring demonic antagonist that became a fan favorite?

The different designer’s and writer’s voices have allowed for a treasure trove of ideas, other interpretations of what Monkey Island is, and other attempts to drive that expensive Mercedes (uh-oh, the weird car analogy is back). What did Ron have planned at the end of LeChuck’s Revenge? Who knows? I certainly don’t. What I do know is we’ve dug up decades of comedy gold in the meantime sailing around the cartoon seas in search of the secret of Monkey Island. Whether we ever find it I don’t think matters. I say, “Big Whoop.”

Larry Ahern, co-director of The Curse of Monkey Island.

Note: This foreword was written for the French release of this book, before Return to Monkey Island was announced.

1 The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) is a computer encoding standard for characters, first issued in the 1960s. It offers a simple way to encode nearly all the characters appearing on a keyboard. In the early days of computers, the graphics of certain games were made up of ordinary letters, numbers, and symbols (like a smiley).

Preface:Adventure by LucasArts

THERE ARE DIFFERENT ways to approach games, particularly video games. A child grabs a ball and has fun knocking it around to get it into a goal, defeat an enemy, or create some sort of competition. Others imagine that the ordinary ball is actually a priceless treasure stolen from a bloodthirsty intergalactic mercenary. You have games and you have imagination. Play of any kind becomes part of a child’s world; it allows the child to use various connected forms of expression to bring to life their internal universe, with their most personal interpretations blending experience with creativity. As the ultimate synesthetic activity, calling on multiple senses all at once, video games have a power that no other game before them has possessed, being at once creative, directive, and stimulating. Video games enable both competition and storytelling, provided that the creators and the systems they establish are finely tuned. When video games first appeared–emerging as a minor form of popular art, much like film about a century ago–they were criticized for being too literal and for being dumbed down for children. It took a number of brilliant gems to prove, as we now know, that those early issues were just the result of youthful folly and the technical limitations of a new medium and new artform. Being the visionary that he is, George Lucas, the genius creator of the film sagas Star Wars and Indiana Jones, began to believe in this new form of artistic expression, seeing in video games the potential to stimulate the imagination with at least as much power as he had recently achieved on the silver screen.

In the early 1980s, Lucas gave a handful of young creators a level of freedom that would never again be seen in video game history. He gave them free rein with time and resources to invent a new mode of storytelling. The result was an incredible series of absolute masterpieces: Maniac Mansion, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, Loom, Day of the Tentacle, Sam and Max Hit the Road, Full Throttle, The Dig, Grim Fandango, and, of course, the Monkey Island series… Ask around: for anyone in the Western world who was a teenager with a computer in the 1990s, at least one of those names will undoubtedly bring back fond memories. From melodies that have become classics to lines with some real zingers, for over a decade, the “adventure games” produced by LucasArts deployed their universes, making their mark on an entire generation of players. That generation invariably continues to cite those games as untouchable classics, unrivaled models, and sources of inspiration. There are probably as many ways to explain the impact LucasArts’ games have had on our collective imagination as there are ways to experience said games, but nonetheless, we’ll do our best…

There is a mythical, almost palpable aura around this generation of games, and The Secret of Monkey Island in particular. More than just a genre, “point & click” or, more plainly, adventure games have been able to distinguish themselves and stand the test of time, in spite of a certain rigidity and harshness of opinion tending toward snobbishness. Adventure games offer a different way to view the video game medium. An adventure game is all about a special connection with the story, characters, places, ambiance, and message. As the adventure game deviated from its cousins, the platform games and action games, it exposed its gameplay as being its greatest flaw. The point & click player unconsciously develops an unprecedented temporal link with the pixel-based backgrounds appearing before them. On a long summer night, with the windows wide open in hopes of catching a breeze, or on a rainy Saturday afternoon at home, lulled by the creaky hum of the hard drive and the noisy blowing of the PC tower, that player would spend hours searching every nook and cranny of the backgrounds, rummaging, combining, experimenting, chatting, and drawing on every possibility offered by the game. That rhythm–that slowness, that temporal aspect–is particular to the adventure game genre. Each “screen” calls you on an adventure and immerses you in a world. Moreover, the adventure game genre can legitimately claim to have offered the best graphics in its heyday. The backgrounds were teeming with details, bringing the game’s world to life and establishing the models defining the limits of gameplay for each player. Environmental storytelling first earned its spurs with the backgrounds of works by Lucasfilm Games. The mouse becomes an extension of the player’s body, directly connected to their vision. The cursor hesitantly sweeps over the screen, thoroughly searching through the masses of pixels. The immersion becomes total thanks to the musical ambiance, with themes that have become classics.

The works of Lucasfilm Games, and later LucasArts, are also renowned for their humor. After all this time, we can say that they are the zaniest games ever created, using physical comedy, deliberately stupid anachronisms, ludicrous situations, and off-the-wall characters. Naturally, they appear to be directly inspired by Monty Python2 and Terry Pratchett,3 with very specific visual references to what would later be known as pop culture, as well as featuring a very clear cultural, postmodern artistic erudition that tugs at the player’s curiosity. For gamers in the ‘80s and ‘90s, occasions for a good laugh while playing were few and far between, and games like Monkey Island, Day of the Tentacle, and Grim Fandango offered their young players cynicism without malice, soft immorality, and perhaps even provocation without darkness or venom.

The Secret of Monkey Island stands out from the studio’s other productions because, indeed, it gave rise to an entire series. And that series has carried on through the years and bears all of the markings of video game production over the last three decades. From a stylistic revolution invoking simplicity and stripped-down representations, to the artistic profusion of the unfinished original trilogy, to a brilliantly produced gem of an episode that calls you on an adventure and serves as the swan song for 2D, to the cursed children of 3D, to the episodic format, the series provided equal measures of upheaval and hijinks for the creators who toiled over it. It underwent just as many mutations as its nascent cultural industry, falling victim to a fatalistic duality balancing profit with artistic dalliance. The series is a fascinating subject of study that this book will humbly attempt to elucidate.

Finally, what makes the work of Ron Gilbert so important is the impressive finesse of his writing, its intelligence, and the hidden subtlety of its thematic vagaries. Indeed, while the author’s main idea is purposefully hidden from the player to become the titular “secret” of Monkey Island, the theme that emerges over the course of the first two installments, and which remains maddeningly incomplete, leaves no doubt in anyone’s mind today. The series’ kaleidoscopic universe and colorful characters exude wistfulness for childhood. Ron Gilbert’s Monkey Island is quite simply a work of nostalgia, a daydream that connects directly to the imaginary worlds of a child, the child who we once were and who curiously resonates with the player who dives back into the game over 30 years later, filling their eyes and ears with the memories of a distant past. A past era made up of “chip tunes,” EGA graphics in 16 colors, floppy disks, midnight snacks, and parents yelling up the stairs for the umpteenth time: “Dinner’s ready!!!”

So… why this book?

A bit more than an homage, the author of this book (yours truly) and, especially, its august publisher felt that it was important to go beyond the nostalgic desire to talk about the good old days when a handful of pixels could knock our socks off. This book’s composition will invite you to discover the rise and fall of the legendary Lucasfilm Games studio, as well as the juiciest details and secrets of the making of each game in the Monkey Island saga. To do just that, we will need to take another look at the rest of LucasArts’ productions and immerse ourselves in the day-to-day experiences of the studio’s handful of talented swashbucklers. Meticulously but, I sincerely hope, not too academically, he chapters of this book will take the time to describe more specifically why each of the games in the series has such a distinct personality and holds a crucial place in video game history. We will travel from island to island, from one era to the next, to retrace a three-decade chronicle of video games.

As you will see, the pages of this book are studded with quotations and references, but they also offer a few snippets obtained directly from some of the creators, and I would like to personally thank, in particular, Peter Chan, Steve Purcell, Dave Grossman, Mark Ferrari, Tim Schafer, Khris Brown, and Larry Ahern, who graciously sat down with me to recount their old anecdotes from their buccaneering days. I was not surprised to discover that, in addition to being talented artists, they are also great people. Finally, there’s a good chance that you may have bought this book in hopes of finally discovering the secret of Monkey Island. Well, after much searching, I will save you a lot of trouble: it is my pleasure to reveal to you that, in fact, the notorious secret closely guarded by Ron Gilbert is…

… oh! Look behind you! A three-headed monkey!!!

About the Author: Nicolas Deneschau

An eclectic connoisseur of Kaiju-Eiga, sci-fi films in black and white, and pirate novels, Nicolas is still trying to find his rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle. Having done a stint writing about films with Cinegenre.net, then taking his writing talents to Merlanfrit, today he collaborates with Third Éditions. Notably, he is the co-author of the book The Saga Uncharted: Chronicles of an Explorer.

2 A famous British comedy troupe that was most active in the 1970s, with the television series Monty Python’s Flying Circus and the films Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), Life of Bryan (1979), and The Meaning of Life (1983).

3 British author of the Discworld book series.

Introduction

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…

Before we discuss the adventures of Guybrush Threepwood, mighty pirate, or dive into the creation of the games, we should first look at the destiny of a man without whom this series of games that dazzled players in the early days of video game history would never have become reality. Our story begins in 1944 in the small California city of Modesto.

George Walton Lucas, Senior, and his wife, Dorothy Ellinore Bomberger, had four children: three girls–Ann, Kathleen, and Wendy–and a scrawny little boy named George Walton, Junior. Let’s set the scene: Modesto was a sleepy little city between Sacramento and San Francisco, and the Lucas family, as devout Lutherans, maintained a strict, religious lifestyle. George Walton, Jr., was a delicate boy. Bullied by his classmates, he spent much of his time devouring the classic adventure stories of Robert Louis Stevenson (Treasure Island) and Daniel Defoe (Robinson Crusoe), as well as collecting numerous comic books (notably Flash Gordon). Illness kept his mother bedridden most of the time, and his father was often absent as he worked to provide for his family. As such, George was more or less left to his own devices and was a mediocre student at best. In the late 1950s, muscle cars became all the rage in California, and young people liked to blast rock ‘n’ roll music while flying down the highway. George Lucas, fascinated by this aesthetic and world of cars, became a fan of automobile racing and pushed his modest studies to the side in hopes of becoming one of the most talented drivers to grace American speedways. However, his dream was short-lived and came to a definitive end when he crashed his Autobianchi Bianchina into a tree at full speed on June 12, 1962. Miraculously, George was ejected from the vehicle, of which all that remained was a burning wreck. The accident made headlines in the local news. That was very nearly the end of the story and you would have been very unhappy to have spent a few dollars on this book.

While he recovered, lucky to be alive, George Lucas decided to get his act together and rededicate himself to school. He attended Modesto Junior College, where he managed to earn a two-year degree. But he also found a new passion: telling stories with the help of a camera. Encouraged by his longtime friend Haskell Wexler, an already experienced cinematographer, George enrolled at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts in Los Angeles. In his class, he made friends with a man named John Milius,4 who introduced him to the work of a popular Japanese director, Akira Kurosawa. Lucas was immediately entranced by the virtuosity of the Japanese master. He praised the incredible potency of Sanjuro and Throne of Blood, and he watched Seven Samurai dozens of times to learn every shot. He discovered the power of images and looks, as well as the science of editing in Kurosawa’s films. The chaining of action shots went on to have significant influence on young George, who appreciated the very particular sense of rhythm capable of masquerading as popular film to more effectively transmit a deeper message… In any case, this new passion seemed more promising than car racing. Lucas’ first films as a student were well received, even acclaimed, like his science-fiction short film Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB, which took first prize in the 1967 National Student Film Festival. That same year, George completed a six-month internship at Warner Bros., where he met another up-and-coming director, Francis Ford Coppola, who would become a friend. Coppola was finishing up filming of a musical starring Fred Astaire and Petula Clark called Finian’s Rainbow.

The two buddies became inseparable, and Lucas got his start as a full-fledged director by creating a documentary about the filming of Coppola’s latest movie, The Rain People. Lucas and Coppola were young idealists filled with new ideas, while the society of the late 1960s clamored for fresh blood to ride the New Wave of cinema coming out of France. So, together, they decided to found their own production company, American Zoetrope, in 1969. In doing so, they hoped to be able to get their respective film projects off the ground while maintaining total creative control. Producer John Calley of Warner Bros. then proposed that George Lucas should adapt his successful short into a feature-length film for theatrical release, dubbed THX 1138.

Very loosely yet clearly inspired by George Orwell’s 1984, the film used a script, originally written by Matthew Robbins and Walter Murch, set in a dark, uncompromising future in which humanity lives in a sedated state and suffers under the yoke of a totalitarian power. A worker, THX 1138, and his partner, LUH 3147, after having unauthorized sexual relations, are sentenced to prison. THX ends up escaping from that white hellhole, while LUH is executed. Lightyears away from the George Lucas universes much more familiar to us today, THX 1138 is a dark, pessimistic, anxiety-inducing film. Still, the movie is striking for its original aesthetic approach and its sense of rhythm, which prominently features both long silences and action sequences. The movie was released in American theaters in March 1971, but its performance was decisively bad: it was a critical and commercial flop. However, its visual choices and uncompromising nature earned it a solid reputation in the years that followed, particularly among young directors whose names you may or may not know: Spielberg, Scorsese, Carpenter, Darabont, etc.

In spite of its undeniable artistic and visual strengths, the poor box office performance of THX 1138 left American Zoetrope and Francis Ford Coppola deep in debt. Coppola decided to take on a project that Paramount Pictures was pressing him to direct, a little film called The Godfather, which, in spite of being a choice made out of desperation, proved to be a good one. Lucas, meanwhile, was upset about the lack of support he was receiving from his fellow director in talks with Warner Bros. He also sensed that their personality differences risked causing permanent damage to their friendship. George distanced himself from American Zoetrope and began working on a small-budget film for Universal Pictures called American Graffiti. At the same time, he decided to create his own modest production company, Lucasfilm Ltd., which we will get back to before long. With the encouragement of his wife, film editor Marcia Lucas, George decided to set aside his philosophical ambitions and deliver a movie that would be lighter and less visceral, fresher and more sincere. The result was an homage to the carefree attitude of 1960s America, in which a group of teenagers leave their worries behind for an evening as they cruise around in gleaming muscle cars while listening to rock legends like Chuck Berry and Fats Domino. Lucas filmed the movie in 29 days with a modest budget, creating a fresh, cheerful film offering nostalgia and catharsis for a society entangled in both the Vietnam War and an economic crisis. American Graffiti was a surprising blockbuster. The movie was released in summer 1973 and was a huge success. On an original budget of $777,000, by the end of its run, the film had brought in $115 million and earned Lucas independence beyond his wildest dreams. What’s more, the movie’s success launched the careers of a number of young actors you may have heard of, including Ron Howard,5 Richard Dreyfuss,6 and Harrison Ford.7 It also gave birth to an all-time classic TV series, the aptly named Happy Days.

Coppola and Lucas finally reunited and buried the hatchet. For Coppola, the massive success of The Godfather allowed him to undertake many other projects; for Lucas, the commercial success of American Graffiti restored his reputation. Coppola asked Lucas to direct a film that was particularly near and dear to his heart, based on a script by his friend John Milius: Apocalypse Now. However, George declined. He secretly dreamed of adapting for the big screen one of his favorite series from his childhood: Flash Gordon. However, the owners of the rights to the pulp franchise featuring intergalactic adventures weren’t willing to hand them over so easily. So, George Lucas would have to create his own universe.

November 1973. The movie studio 20th Century Fox, led by Alan Ladd, Jr., agreed to finance George’s next project, a science-fiction film given the grandiloquent title The Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller.8The project was ambitious and would likely require the development of an unprecedented number of special effects. So, Lucas decided to found the studio Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) within his production company, Lucasfilm Ltd., so that he could retain total creative control over the visual aspects of the film. However, above all, George Lucas aimed to invest in special effects, which he foresaw as being an essential element for big-budget movies to be produced in the years to come. He installed the pioneering John Dykstra at the head of ILM, with support provided by model designer Colin Cantwell and the brilliant conceptual artist Ralph MacQuarrie.

Casting for the film began in August 1975 at the offices of American Zoetrope. Director Brian de Palma9 assisted George with this task. While famous actor Toshiro Mifune10 was for a time considered for the role of Obi-Wan Kenobi, he was ultimately replaced by veteran actor Alec Guinness. Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, and Mark Hamill were then hired to play the leading roles. Cunning as ever and possessing an unparalleled sense of business, Lucas obtained from Fox the rights to all future merchandizing tied to the saga. This bold move would pay off big time. Filming of Star Wars began on March 22, 1976, in Tunisia, then continued in London, finishing on July 23 of the same year.

The first cut of the film was a complete disaster: it was flat, boring, and totally conventional… Everything that Lucas wanted to avoid, as he was mainly targeting the movie at a teenage audience. Even though the rushes were then placed in the capable hands of George’s wife, Marcia Lucas, and editor Paul Hirsch, the release had to be pushed back to summer 1977. The extra 10 months this gave them were dedicated exclusively to creating the complex special effects needed for the film’s various scenes. In October 1976, Lucas collapsed in the middle of the studio from what he thought was a heart attack. But the doctors diagnosed the cause as acute stress, and they encouraged him to rest. However, the countdown had started, and Lucas only had a few months remaining to finish his film. He put all his energy and money into the project, about which Fox executives were starting to have doubts.

John Dykstra proved to be crucial to the success of the film’s technical aspects. He was probably one of the first people to buy into the idea that computers had a major role to play in helping create shots that were too complex or costly to be filmed using traditional techniques. His vision was likely a key element for the future creation of video games. Dykstra proceeded to invent the Dykstraflex system by mounting a large camera on a rig whose movements were controlled by a series of computers. Remember that in the 1970s, all of this was very experimental, and a machine with the power of a simple pocket calculator occupied the space of a large antique wardrobe. With the camera controlled by computers, it was able to carry out very precise, rotating shots of fixed objects such as models, creating the illusion of movement.

The final cut incorporating all the post-production effects was finally finished on time after a lot of painstaking work. The soundtrack by John Williams exceeded all of Lucas’ expectations and enhanced the entire production, resulting in the film we know and love today. In a few words: a new kind of film that was gripping, epic, well-paced, and visually extraordinary. From the start, Lucas imagined a coherent universe based on the serials11 of his childhood, and he convinced Fox to produce two additional movies. You can feel this in the construction of the original episode, with the unprecedented depth of its universe.

Star Wars premiered on 37 screens in the United States on May 25, 1977. Audiences fell head over heels for it. While Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, released the previous year, set a new standard for blockbusters, Star Wars became the quintessential example. Everyone wanted to see it; the theaters were packed day after day. Fox’s stock price doubled in record time. Lucas, meanwhile, took a well-earned vacation one week after the film’s release. On a beach in Hawaii, his friend Steven Spielberg confided in him that he wanted to direct a new James Bond. Lucas stopped him there and told him he had a better idea: a movie about an adventurer in the 1940s who goes off in search of mysterious artifacts while fighting the Nazis… The rest is history.

With the success of Star Wars under his belt and confident in his universe, George Lucas decided to produce the sequels on his own. Going forward, Fox would simply serve as the distributor of the films in American cinemas. However, Lucas found that he couldn’t handle everything singlehandedly, so he decided to entrust the directing of The Empire Strikes Back to one of his former university professors, veteran director Irvin Kershner.12 Filming lasted through all of 1979, for a theatrical release on May 21, 1980. It was another massive success. Americans flooded the theaters; the famous paternal twist13 stunned the media and fans worldwide.

While work on the Star Wars saga was underway, the script for Indiana Smith, who would later become Indiana Jones per the wise advice of Steven Spielberg, was close to being finished by Lawrence Kasdan. Lucas would be the producer and his friend Spielberg would direct the film. Raiders of the Lost Ark was released on June 12, 1981, and was wildly successful with both critics and audiences. George Lucas was officially crowned the independent film king of Hollywood. Additionally, during this same period, Lucas produced one of the greatest Akira Kurosawa films, Kagemusha. George had never ceased to be an admirer of the Japanese director.

While the sequel to The Empire Strikes Back was being prepared, Spielberg worked on The Temple of Doom, the second installment in the Indiana Jones series, which was in the writing process.

But Lucas didn’t want to stop there. He fully understood the magnitude of the universes he had created and their success with young fans. Movie merchandise took off, more and more films were produced with special effects,14 Sony launched its CDP-101, the first audio CD player, and the American youth spent much of their time and money at gaming arcades. What’s more, Lucasfilm was earning wild levels of profit and was thus threatened with heavy taxes. To minimize that financial hit, there was one solution: invest in new technologies. This convergence of facts gave Lucas the brilliant idea to create a new team within his special effects company ILM, which he did on May 1, 1982. Thus, the Computer Division was born.

4 Who, a few years later, went on to write Apocalypse Now and direct the equally popular Conan the Barbarian.

5 Who directed Apollo 13, Willow and, as it turns out, Solo: A Star Wars Story.

6 An actor who appeared in Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

7 An actor who needs no introduction: Blade Runner, Star Wars, Indiana Jones, etc.

8 An early version of the name Luke Skywalker, after the original name Mace Windy.

9 Who was also doing auditions for his next film, Carrie.

10Seven Samurai by Akira Kurosawa.

11 Serials were episodic films based on serialized novels that were particularly popular from the 1930s to the 1950s.

12Eyes of Laura Mars, RoboCop 2, Never Say Never Again.

13 “I am your father!”

14 In 1981, E.T., Blade Runner, and Tron all became milestones for this category.

Part 1

Chapter 1: Lucasfilm Games™

The number-one objective of the Computer Division wasn’t to work on video games specifically, but rather to master the production of digital special effects for feature-length films and various other audiovisual productions. The team’s first success was integration of the “Genesis effect” into the movie Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan, directed by Nicholas Meyer (1982), an animation meant to reconstruct landscapes in the form of fractal images. Having secured its budget, the team was able to dive deep into research and development to come up with new possibilities for digital imaging.

Before long, Atari, which at the time was the biggest player in the American video game industry, set its sights on the work accomplished by ILM and proposed a collaboration with Lucas. The CFO of Lucasfilm Ltd. managed to convince Atari to pay the modest sum of $1 million in exchange for a vague “see what you can do!” Ed Catmull was officially the first employee of the Computer Division. Promoted to the rank of director, he was in charge of establishing the scope and goals for his division, as well as selecting the team with which he’d collaborate. He told Rolling Stone magazine that George wanted them to make games… and by the end of the year, they had a game designer!15 Lucas said “jump” and Ed Catmull said “how high?” He quickly hired Peter Langston, an ultra-talented Unix developer, who he poached from a Wall Street firm (remember this name, we’ll come back to him later on in this book…).

Of course, we have to remember the context: the Computer Division had to invent something; it had to start from scratch and imagine what the future of video game creation might look like. As such, it’s no surprise that the team that formed was a motley crew of different talents. Langston was the very first employee of the Lucasfilm Games Group within the Computer Division: “In May of 1982, The Computer Division of Lucasfilm Ltd. hires me to start a new project in electronic and computer games, and I move from New York City to Marin County, California, and I start hiring staff, and we sign a profitable licensing agreement with Atari, and I give a lot of interviews,”16 he remembers with a laugh. He then established the basis of game design for the team’s future productions. David Fox, Rob Poor, and David Levine soon joined him. They all worked tirelessly to come up with the technology capable of supporting George Lucas’ new ambitions. Their only instruction? “Don’t touch Star Wars!” That was a big disappointment for David Fox: “We were told right up front that we were not allowed to do Star Wars titles. I was really upset–I had joined the company because I wanted to be in Star Wars!” And Steve Arnold adds: “We were creating a culture that was designed around innovation… We had the brand of Star Wars, the credibility of Star Wars, and the franchise of Star Wars, but we didn’t have to play in that universe. We were a group that lived inside a super-creative, technologically astute company and we got to do our own invention… We got to make up our own stories and call them Lucasfilm.”17

The advantage of such a small team, given total freedom, was that they could weave their way through the tentacular organization that was ILM. The team was able to take advantage of the most powerful graphics machines on the market, used by the Film Division. They were even able to procure the services of the graphics team to work on their preliminary visuals or simply have the studio’s specialized teams create sound effects for them. This flexibility allowed them to spend their first several months focusing solely on game design while bearing in mind that they needed to contend with the enormous technical constraints of the machines available on the at-home gaming market at the time.

Rebel Rescue™ & Ballblazer™

In his earliest days at the studio, David Fox spent his time with Loren Carpenter, the graphics developer responsible for the famous “Genesis effect” in Star Trek. Carpenter, who loves a good challenge, kept a curious and watchful eye on the Games Group. With Fox’s encouragement, he decided to lend them a hand. As Fox tells it: “We lent him an Atari 800 and he took it home. Within a matter of days, he learned the basics of the assembly language for the 6502 processor and understood how the Atari handled its display of graphics. Within a week he came back to the office with a functioning demo. He had created a real-time generator of fractal images within the limits of the Atari’s 48 KB of memory and primitive resolution. It was incredible! It was running at about eight to ten frames per second and was probably one of the coolest things we had ever seen on a microcomputer.”18 Upon seeing the result, being the good Star Wars fan that he was, David Fox imagined how he could employ such an engine within a game. Thus, the Rebel Rescue project was born. “Star Wars was an eye-opening experience for me. I wanted the game to take place in that universe. We didn’t have permission to use the saga’s characters, but we were able to take very heavy inspiration from the style of the ships and places in the movies. Any resemblance between the game and the scenes on planet Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back is, of course, pure coincidence…” David Fox remembers humorously. Rebel Rescue became a flight simulator in which the player controls a sort of vessel inspired by the X-Wing from Star Wars, with the goal being to save rebel pilots lost on the surface of a planet generated with fractal images. “We didn’t have a deadline, so we had plenty of time to screw things up!” jokes the game designer. “After a few months of work, you could fly and control the ship with a joystick, and it was a pretty fun game. But there was still something missing and we had to show it to other people to figure out what worked.” Charlie Kneller joined the Games Group and improved the ship’s flight dynamics. He also began optimizing the fractal engine. Meanwhile, Peter Langston continued expanding the team’s influence. He designed the music and sound for Rebel Rescue (renamed Rescue on Fractalus) and kicked off production of another game, with David Levine serving as the director. When development seemed to be reaching the finish line, the High Admiral, George Lucas, paid a single visit to the Games Group… He found Rescue on Fractalus to be pretty fun, but he was surprised by the lack of shooting on the ship. He recommended to Fox that the game should allow the player to shoot at enemies and also include bad guys pretending to be rebels needing to be saved in order to add excitement to the game. When the leader speaks, you do as you’re told, even if that means significant production delays for the game. “We secured permission from Atari–who would be publishing the game–to not mention the aliens in the manual or in any of the PR. In fact, the disguised aliens19 don’t appear though the first four or five levels of the game, so that just as you get into the habit of landing, turning off the engine, seeing a guy in a space suit, and unlocking the door for him, you might not notice that the figure approaching has a green head. If the door was open, you’d be boarded and have to fly like mad into space and hopefully expel him from the airlock. Despite Rebel’s rudimentary graphics, I recall numerous people regaling [me] with tales of falling from their chairs in fright and getting a huge adrenaline rush from the shock value,” recalls David Fox.

Meanwhile, David Levine reused Loren Carpenter’s engine to try out another design idea, a project initially named Ballblaster, then Ballblazer. Instead of aliens and space ships, the game invited two players to face off in matches of a sport similar to soccer, in which machines called “rotofoils” must get the “plasmorb” into the opposing goal. The first-person view enabled 360-degree movement over a field generated in real time. While the controls seemed quite finicky, the game nonetheless distinguished itself for being well crafted. Ballblazer even improved Loren Carpenter’s engine by integrating anti-aliasing, a revolutionary process at the time, which smoothed out the enormous pixels of the 8-bit Atari. Notably, even the game’s introductory music was randomly generated, following a tempo and rhythms to accompany the match, an idea that later gained traction, as we will see…

The two games were delivered to Atari in return for the million-dollar “see what you can do!” Steve Arnold, who was a newcomer to the Lucasfilm Games Group team at the time, remembers: “The problem was that Atari basically gave away copies of the game. The games were sent under extreme cone-of-silence, non-disclosure, eyes-only, burn-after-reading security… but still appeared shortly thereafter on the underground networks… and the pirated versions even won some awards…”20 Users of the Atari 800 at the time could take advantage of the earliest network connection modems to exchange files, and pirated copies of Rescue on Fractalus and Ballblazer were popular targets. What’s more, Tim Schafer, the master architect of Monkey Island who joined the team a few years later, shares a funny anecdote. When interviewing for the position, “I called David Fox right away […] I told him how much I wanted to work at Lucasfilm, not because of Star Wars, but because I loved ‘Ball Blaster.’ ‘Ball Blaster, eh?’ he said. ‘Yeah! I love Ball Blaster!’ I said. It was true. I had broken a joystick playing that game on my Atari 800. ‘Well, the name of the game is Ballblazer,’ Mr. Fox said, curtly. ‘It was only called Ball Blaster in the pirated version.’ Gulp… Totally busted. It was true: I had played the pirated version. There, I said it.”21

At the time, most video games stuck to a very classic structure based on difficulty, a number of lives available, and very well-established arcade routines. The Computer Division had a different approach, and David Fox offers this explanation of their philosophy: “I would say when we’re designing a game, the aim is to create some sort of an experience. […] We really want to get someone feeling like they’re in a new universe, and to create an experience of exploring a new universe. It’s the sort of thing that happens in a George Lucas film. It’s like you’ve been transported to somewhere else. Most of us like that feeling and we want to be able to transport the person to another universe too, through a game that’s really different.”22

It’s worth noting, from today’s point of view, in this era of digital media, the packaging for the games looks completely ludicrous. The boxes of both games and their contents were produced as if for a high-class feature-length film. Gary Winnick created the concept art with David Fox and David Levine for their respective titles, then life-sized models of a rotofoil and a spaceship were built by ILM to appear on the jackets and advertising materials. Finally, a photo shoot with David Fox, completely made over to look like a spacecraft pilot, provided illustrations for the game’s guide. It was Lucas-style extravagance…

Presented at CES in Las Vegas in 1984, the two games caught the attention of the trade show’s technophile audience. Some journalists doubted that such an engine could be real and looked for a hidden VCR that might be playing pre-recorded images on the screens. But they were indeed real-time demos of games on an Atari 800. The commercial success was relatively modest, but nevertheless, Lucasfilm now had an experienced team ready to make use of their cutting-edge technology for future games…

Koronis Rift™ & Eidolon™

Noah Falstein was the newbie on the team. Peter Langston hesitated for quite some time before hiring him: “Peter wasn’t very enthusiastic about bringing me on board because I had previously worked at Williams Electronics on the arcade game Sinistar, and nobody in the group had previous video game development experience. He was worried that I wouldn’t be able to bring in new concepts given that I was already a veteran creator, at the ripe old age of 26… However, after lending a hand on Rescue on Fractalus, I got the idea for a game with a new design called “Tanks A Lot”23 and I immediately got the green light, even before the budget and schedule had been set.”24 The new concept, which eventually took the name Koronis Rift,25 once again based on the fractal engine, put the player in control of a vehicle belonging to a futuristic treasure hunter. The goal was to discover artifacts and long-lost technologies abandoned by the ancient inhabitants of a faraway planet. It blended action with strategy and added a bit of complexity to the rudimentary concepts of Rescue on Fractalus. However, even though at the time of its release the media recognized it as being a beautifully made game, its searing difficulty leaves me unwilling to recommend it to my readers…

Also in 1985, a newcomer, Charlie Kenner, was working on another game, The Eidolon, based on the studio’s historic engine. The game propelled players into a heroic fantasy world where they had to make their way through caverns and battle creatures like trolls and gnomes to escape. As it was, the title was a likely precursor to the famous (and incredible) Dungeon Master, made by FTL Games, and perhaps even more so to Ultima Underworld by Blue Sky Prod. It was an ancestor to first-person dungeon crawlers,26 but with real-time scrolling, faithful to the Games Group’s other productions. The game is fluid, difficult, and handles well… The game design remained basic, but the concept was there and would only be improved upon in the years that followed.

Abandoning Atari, which changed hands several times during that period, Peter Langston took the opportunity to switch the studio to a new distributor, Epyx, which boosted their sales. While the two games weren’t the best produced in-house at the time, they offered the opportunity to experiment and to develop solid experience among the young developers.

Lucasfilm Games™

The year 1985 was one of change for Lucasfilm, and for the Games Group in particular. While Peter Langston continued to direct the creative side of the studio, he delegated the sales and finance aspects to Steve Arnold, who came over from Atari. George Lucas was a businessman, and Lucasfilm, even though it served as an experimental laboratory, needed to be profitable. According to Arnold, when he first joined the Games Group: “It was a bunch of hippies in Star Wars T-shirts. They started their day around 10 in the morning, but finished very late, and you could immediately feel that the environment was particularly conducive to creativity and humor.” One of Steve Arnold’s initiatives was to encourage the technical teams to come up with anti-piracy systems to prevent the distribution of illegal copies and to try to generate profit from game production. Then came the second big change for the game developer: it received a recognizable name and label. Thus, the Games Group officially became “Lucasfilm Games.” From then on, games would be produced, published, and distributed in-house under the new brand.

Alongside Lucasfilm Games, a second branch of the original Computer Division, led by Ed Catmull, was spun off. Renamed Pixar,27 its big players included Alvy Ray Smith and one John Lasseter28… Within weeks, Pixar was sold to Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple, and went on to become a massive, successful studio, reigning as the undeniable and uncontested world champion of CGI animation. They did OK for themselves, I guess.

For Lucasfilm Games, George Lucas’ instructions were clear: “Stay small, be the best, and don’t lose money!” However, Lucas rarely castigated or imposed restrictions on the video game teams. According to the director of the game Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, Hal Barwood, Lucas was like “that rich uncle who gives you Christmas gifts each year, but who you almost never see.”29 Peter Langston adds: “I think from the start, he needed us to prove that we understood the business, which is why he was as involved as he was at the beginning. He had seen what the Computer Division had done with the technology in the area that he knows about: film. And he said, ‘This is great, I want to do this more elsewhere.’ Doing it in this area that he didn’t know much about… He was proud of us, and respectful. I think maybe he even had the sense that he wouldn’t want us to come in and say, ‘this movie should have this change,’ so he wasn’t going to do that to us either.”30 According to another developer, Chip Morningstar, Lucas viewed Lucasfilm Games as the Lost Patrol:31 nobody really knew who they were or where they were, but they had to be somewhere…

In spite of impressive creativity, with the releases of PHM Pegasus, a military simulation; Labyrinth, an early graphic adventure game; the Mirage Project, a life-sized X-Wing flight simulator; and Habitat, the first true graphic-based MMORPG, Lucasfilm Games still hadn’t found its path, its trademark, its identity. Certain game publishers began to specialize–in arcade games, in shooters, in role-playing games. But at Lucasfilm Games, in keeping with the philosophy of George Lucas, the main focus was on telling stories. And while, at the time, storytelling in video games remained shaky, there was already a genre building a solid reputation in this area. A genre capable of combining the desire for a real story with unbridled creativity. A genre that was ready to explode…

15Rolling Stone, June 10, 1982.

16http://www.langston.com/LFGames/

17https://www.usgamer.net/articles/i-actually-was-hunting-ewoks-lucasfilm-games-the-early-years

18https://www.electriceggplant.com/media/RG44_RescueOnFractalus.pdf

19 The enemy aliens in Rescue on Fractalus are called Jaggis.

20Rogue Leaders, The Story of LucasArts (Rob Smith).

21https://www.apl2bits.net/2016/02/29/tim-schafer-lucasfilm-ball-blazer/

22https://www.usgamer.net/articles/i-actually-was-hunting-ewoks-lucasfilm-games-the-early-years

23 A great pun indeed!

24Rogue Leaders, The Story of LucasArts (Rob Smith).

25Koronis Rift gets its name from Noah Falstein’s college thesis entitled: Koronis Strike: A Computer Simulation Game of Mining and Combat in the Asteroid Belt.

26 The “dungeon crawler” genre is characterized by first-person exploration of labyrinthine dungeons according to the formula “door-monster-treasure.”

27 From the nickname the employees had given to their Silicon Graphics work stations, which were digital compositing computers.

28 He went on to become the head of Pixar Animation Studios and the creator of Toy Story, Cars, etc.

29Rogue Leaders, The Story of LucasArts (Rob Smith).

30https://www.usgamer.net/articles/i-actually-was-hunting-ewoks-lucasfilm-games-the-early-years

31 A reference to The Lost Patrol, an American film by John Ford (1934).

Chapter 2: From interactive fiction to Point & Click™

Given that today’s adventure games have marginal popularity and are nowhere near as successful as the big blockbusters, it’s hard to imagine that they were once the hottest genre of video game, with each title eagerly awaited like the Messiah. From the early 1980s and for almost two decades, adventure games regularly appeared on the covers of video game magazines and provided the most celebrated sagas of the microcomputer era. Then, from the mid-1990s, the genre began to decline, to the point of becoming a retro, nostalgic pleasure, though current experiments to revive it are showing undeniable inventiveness. The adventure game offered each studio the opportunity to show off its talents, both technical–as most of the games were showpieces for graphics and audio in their day–and narrative, since the genre was one of the only ones to offer players an elaborate, well-developed scenario, whereas action games limited those aspects to a bare minimum. Before we dive into the history and creation of the Monkey Island series, we first need to go back in time and return to the origins of the genre, as well as review how it has evolved and its impact on video game history, in order to better understand what Ron Gilbert’s series represents in the hearts of so many of those who explored its tropical islands in the early 1990s.

Wander and Colossal Cave Adventure™

Colossal Cave Adventure is often cited as the very first adventure game ever. However, a very serious contender for that title was long forgotten before re-emerging from digital obscurity in 2015. The game in question was created by one Peter Langston (as you’ll remember, he was employee number one of the Lucasfilm Games Group: everything is connected), a young computer nerd who had already created Empire, the first-ever strategy game, in 1972. In 1974, he created Wander. At the time, the term “video game” didn’t really exist yet, and Langston himself referred to his software as a “tool for writing non-deterministic fantasy stories.” Langston recalls, “I came up with the idea for Wander and wrote an early version in HP Basic while I was still teaching at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. That system limited names to six letters, so: WANDER, EMPIRE, CONVOY, GALAXY, etc. Then, I rewrote Wander in C on Harvard’s Unix V5 system shortly after our band moved to Boston in 1974. I got around to putting a copyright notice on it in 1978.”32 However, Wander wouldn’t receive historic recognition until decades later. French journalist Raphaël Lucas explains: “The first amateur game developers were university professors and students; they never made the effort to preserve their video games. Moreover, on PLATO (the first networked computer system, created in the late 1960s), the servers were regularly wiped of these freeloading programs that slowed down access to the main programs, which were used to teach classes.”33Wander largely pioneered game elements that would constitute the earliest text-based adventure games. In a question-answer format, the game calls on the player to find the right responses to continue progressing through a branching story, much like in “choose your own adventure” books. The interface was rudimentary and the options were few, but the foundations were there and would be fully established a year later.

In 1975, a broken heart led William Crowther to seclude himself for a few long months in front of his PDP-10 work computer, on which he developed Colossal Cave Adventure.34 The young computer programmer, who by day worked on creating ARPANET,35 was going through a divorce from his wife, Pat Crowther, and found himself separated from his two daughters. When they came to visit him, he would amuse himself by creating for them little computer challenges that were accessible in spite of the austerity of the interface. In an interview given in 1993, he recounts: “I had been involved in a non-computer role-playing game called Dungeons & Dragons at the time, and also I had been actively exploring in caves–Mammoth Cave in Kentucky in particular. Suddenly, I got involved in a divorce, and that left me a bit pulled apart in various ways. In particular, I was missing my kids. Also, the caving had stopped, because that had become awkward, so I decided I would fool around and write a program that was a re-creation in fantasy of my caving, and also would be a game for the kids, and perhaps some aspects of the Dungeons & Dragons that I had been playing. My idea was that it would be a computer game that would not be intimidating to non-computer people, and that was one of the reasons why I made it so that the player directs the game with natural language input, instead of more standardized commands. My kids thought it was a lot of fun.”36 In Colossal Cave Adventure, the player reads little paragraphs that describe the geographic location of their avatar, as well as the choices they have before them, just like in “choose your own adventure” novels. The player can then interact by using a combination of two words that seem logical to them, like “go south” or “take sword.” In 1975, William Crowther published his game on ARPANET. In 1976, with permission from the original creator, programmer Don Woods made improvements to the game, ported it to different systems, and embellished its universe with names and places directly inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Woods continued to improve upon his new version for over 20 years. Up into the early 1980s, Colossal Cave Adventure was a major influence on budding creators, to the point of spawning its own genre known as “interactive fiction.”

Sierra On-Line™

In 1978, Ken Williams, a young, 25-year-old computer scientist living in Los Angeles with his wife, Roberta, was working on programming accounting software for a client. In order to complete development on time, he brought home a Teletype Model 33 terminal so that he could continue work outside the office. Williams was hoping to soon jump into the software market for the Apple II, but he needed an unexploited niche that would allow him to stand out from the crowd. While perusing the catalogue of downloadable programs for his machine, by chance, he came across Colossal Cave Adventure. After buying it, he suggested to his wife that they play it together. Roberta was fascinated with the universe and the endless possibilities offered by such an interface. Discovering that there wasn’t much competition in the gaming market, she decided to write the hook for a new story she called Mystery House, very loosely inspired by the Agatha Christie novel And Then There Were None. Roberta convinced her husband to spend the next two months developing the game on an Apple II lent to them by Ken’s brother. She quickly realized that the text alone might seem too austere for the mass market and that the graphics capabilities offered by the Apple computer could greatly enrich her story. So, the couple invested in a VersaWriter, a machine capable of converting line-based drawings into digital images. Coding of the game was completed on May 5, 1980, featuring over 70 illustrations. After packaging the game by hand and creating their own company, On-Line Systems, Ken and Roberta bought ad space in Micro