25,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

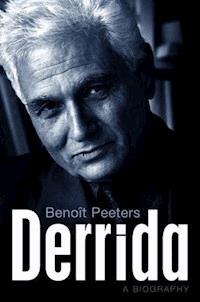

This biography of Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) tells the story of a Jewish boy from Algiers, excluded from school at the age of twelve, who went on to become the most widely translated French philosopher in the world – a vulnerable, tormented man who, throughout his life, continued to see himself as unwelcome in the French university system. We are plunged into the different worlds in which Derrida lived and worked: pre-independence Algeria, the microcosm of the École Normale Supérieure, the cluster of structuralist thinkers, and the turbulent events of 1968 and after. We meet the remarkable series of leading writers and philosophers with whom Derrida struck up a friendship: Louis Althusser, Emmanuel Levinas, Jean Genet, and Hélène Cixous, among others. We also witness an equally long series of often brutal polemics fought over crucial issues with thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, John R. Searle, and Jürgen Habermas, as well as several controversies that went far beyond academia, the best known of which concerned Heidegger and Paul de Man. We follow a series of courageous political commitments in support of Nelson Mandela, illegal immigrants, and gay marriage. And we watch as a concept – deconstruction – takes wing and exerts an extraordinary influence way beyond the philosophical world, on literary studies, architecture, law, theology, feminism, queer theory, and postcolonial studies.

In writing this compelling and authoritative biography, Benoît Peeters talked to over a hundred individuals who knew and worked with Derrida. He is also the first person to make use of the huge personal archive built up by Derrida throughout his life and of his extensive correspondence. Peeters’ book gives us a new and deeper understanding of the man who will perhaps be seen as the major philosopher of the second half of the twentieth century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Derrida

DerridaA Biography

Benoît Peeters

Translated byAndrew Brown

polity

First published in French as Derrida © Flammarion, 2010

This English edition © Polity Press, 2013

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press350 Main StreetMaiden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-7456-6302-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

PART I JACKIE 1930–1962

1 The Negus 1930–1942

2 Under the Sun of Algiers 1942–1949

3 The Walls of Louis-le-Grand 1949–1952

4 The École Normale Superieure 1952–1956

5 A Year in America 1956–1957

6 The Soldier of Kolea 1957–1959

7 Melancholia in Le Mans 1959–1960

8 Towards Independence 1960–1962

PART II DERRIDA 1963–1983

1 From Husserl to Artaud 1963–1964

2 In the Shadow of Althusser 1963–1966

3 Writing Itself 1965–1966

4 A Lucky Year 1967

5 A Period of Withdrawal 1968

6 Uncomfortable Positions 1969–1971

7 Severed Ties 1972–1973

8 Glas 1973–1975

9 In Support of Philosophy 1973–1976

10 Another Life 1976–1977

11 From the Nouveaux Philosophes to the Estates General 1977–1979

12 Postcards and Proofs 1979–1981

13 Night in Prague 1981–1982

14 A New Hand of Cards 1982–1983

PART III JACQUES DERRIDA 1984–2004

1 The Territories of Deconstruction 1984–1986

2 From the Heidegger Affair to the de Man Affair 1987–1988

3 Living Memory 1988–1990

4 Portrait of the Philosopher at Sixty 417

5 At the Frontiers of the Institution 1991–1992

6 Of Deconstruction in America 451

7 Specters of Marx 1993–1995

8 The Derrida International 1996–1999

9 The Time of Dialogue 2000–2002

10 In Life and in Death 2003–2004518

Notes

Sources

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

I can never thank Marguerite Derrida enough for placing her confidence in me, without which the present work would have been unimaginable. She gave me free access to the archives and answered my countless questions with patience and precision. I am also extremely grateful to Pierre and Jean, the sons of Marguerite and Jacques Derrida, as well as to René and Évelyne Derrida, Janine and Pierrot Meskel, Martine Meskel, and Micheline Lévy.

Many of Derrida’s archives are kept at IMEC, the Institut Mémoires de l’Édition Contemporaine, at the Abbaye d’Ardenne. It was a particular pleasure to work there. Thanks are due to the whole of the team, in particular to Olivier Corpet, the general director, to Nathalie Léger, deputy director, to Albert Dichy, literary director, and to José Ruiz-Funes and Mélina Reynaud, who are in charge of the Derrida collection and his correspondence. Their friendly assistance and their competence have been of the greatest value to me. I must also thank Claire Paulhan, who suggested more than one fruitful path for me to follow.

The other part of Jacques Derrida’s public archives is preserved in the ‘Special Collections’ of the University of California, Irvine. Thanks to Jackie Dooley, Steve McLeod, and their whole team for their great efficiency.

Particular thanks must also go to Patricia de Man, Jacqueline Laporte, Dominne and Hélène Milliex, Christophe Bident, Éric Hoppenot, Michael Levinas, Avital Ronell, Ginette Michaud, Michel Monory, Jean-Luc Nancy and Jean Philippe, as well as to Marianne Cayatte (archives of the Lycée Louis-le-Grand), André Vivet (Association des Anciens Élèves du Lycée Montesquieu in Le Mans), Françoisé Fournie (archives of Gérard Granel), Myriam Watthee-Delmotte (Henry Bauchau collection in Louvainla-Neuve), Catherine Goldenstein (Paul Ricoeur collection in Paris), Bruno Roy (archives of Roger Laporte), Claire Nancy (archives of Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe), and to all those who have enabled me to find rare letters or documents.

A huge thank you to those who have helped me, with their advice, their remarks, or their encouragements: to Valérie Lévy-Soussan, first and foremost, for lending me her ear, her advice, and her support every day, but also to Marie-Françoise Plissart, Sandrine Willems, Marc Avelot, Jan Baetens, Jean-Christophe Cambier, Luc Dellisse, Archibald and Vladimir Peeters, Hadrien and Gabriel Pelissier. Thanks also to Sophie Dufour, who transcribed several quotations, with both care and enthusiasm. And particular thanks to Christian Rullier: he knows why.

To Sophie Berlin, director of the Human Sciences department at Flammarion, I am immensely indebted. Without her, I would never have had the idea of embarking on this project, nor the energy to bring it to completion.

Translator’s Acknowledgements

Thanks to Benoît Peeters for replying so readily to my questions and generously providing me with original source materials. Thanks also to Jean-Pacal Pouzet, Chloé Szebrat, and Jane Horton for help and advice. And thanks, most of all, to Justin Dyer for his scrupulous copy-editing and ability to track down the most recalcitrant translations of Derrida and company into English. All mistakes are my own (toutes les erreurs me sont propres). A few further reflections on Derrida and biography can be found at http:IIbenequildatuit. blogspot.co.uk.

No one will ever know the secret from which I write and the fact that I say it changes nothing.

Jacques Derrida, ‘Circumfession’

Algiers, early twentieth century.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Jackie Derrida, aged two.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Sitting on the car with his father, his mother, and his brother René.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Family group: Jackie is in the middle, on his mother’s knees.

(Derrida: personal collection)

At the primary school in El Biar, 1939. Jackie is in the second row (second from right).

(Derrida: personal collection)

At the Lycée Ben Aknoun in 1946 (third row, third from left). In the second row, the blurred face is that of Jackie’s friend Fernand Acharrok.

(Derrida: personal collection)

In El Biar with his friends in the football club (Jackie is in the second row, smiling).

(Derrida: personal collection)

With his mother, summer 1950.

(Derrida: personal collection)

In an Algiers street, shortly before his departure for Paris.

(Derrida: personal collection)

At the wheel of his father’s car.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Jackie at fi fteen. The photo is dedicated to one of his girlfriends.

(Derrida: personal collection)

At the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, fi rst year of khâgne (1949–50), wearing the grey boarders’ overcoat.

(Derrida: personal collection)

The three boys from Algiers in khâgne. From left to right: Derrida, Jean Claude Pariente, and Jean Domerc.

(Derrida: personal collection)

1950–1, second year of khâgne. Jackie is in the third row, third from right. On his right, his friend Michel Monory. The teacher is Roger Pons.

(Derrida: personal collection)

1951–2, third year in khâgne. Jackie is in the front row, fourth from left.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Masters and friends

Edmund Husserl c. 1920.

(© La Collection/Imagno)

Martin Heidegger in 1960.

(© Ullstein Bild/Roger-Viollet)

Antonin Artaud in 1947.

(© Ministère de la Culture/

Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Dist. RMN-Denise Colomb)

Jacques Lacan in 1967.

(© Botti/Stills/Gamma)

Jean Genet in 1956.

(© édouard Boubat/Rapho)

Paul Celan.

(© Photo Gisèle Celan-Lestrange/Fonds Paul Celan/Archives IMEC)

Michel Foucault.

(© Bettmann/CORBIS)

Philippe Sollers in the early 1960s.

(© AFP)

Emmanuel Levinas in 1988.

(© Ulf Andersen/Gamma)

Paul Ricoeur in 1970.

(© Yves Leroux/Gamma)

At the corner of the Boul’Mich and the rue Souffl ot, the favourite cafés of Derrida and his friends in the early 1950s.

(Private collection)

The École Normale Supérieure in the rue d’Ulm (© Jean-Philippe Charbonnier/Rapho) at the period when Louis Althusser (above) was teaching there.

(© Fonds Louis Althusser/Archives IMEC)

Jacques Derrida, c. 1960, in Prague, in Marguerite’s family.

(Derrida: personal collection)

On the ship Le Liberté taking Jacques to the United States for the fi rst time with Marguerite, in 1956.

(Derrida: personal collection)

With his sons, Pierre, born in 1963 (right), and Jean, born in 1967 (below).

(Derrida: personal collection)

On Le France in September 1971 with his niece Martine Meskel.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Tableau vivant of the painting The Massacre of the Innocents, c. 1975, in the house of the Adamis in Arona. In the foreground, Jean, Marguerite, and Jacques Derrida. On the right, Camilla Adami; in the background, Valerio Adami.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Cerisy-la-Salle: the Nietzsche conference in 1972. From left to right: Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, Maurice de Gandillac, Pierre Klossowski, Jacques Derrida, and Bernard Pautrat.

(© Archives de Pontigny-Cerisy)

Cerisy-la-Salle, 1975, with Francis Ponge.

(© Archives de Pontigny-Cerisy)

The sisters Sylviane (on the left) and Sophie Agacinski, Paris, July 1966.

(© Rue des Archives/AGIP)

Photo booth, 1970s.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Letter from Jacques Derrida to Gérard Granel, sent from Nice, 29 December 1989. Most of Derrida’s correspondents found his handwriting extremely diffi cult to decipher.

(Derrida: personal collection)

In June 1979, at the Estates General of Philosophy held in the main ‘amphi’ (amphithéâtre or lecture hall) of the Sorbonne (© Marc FontaneL/Gamma), there was a brief altercation between Jacques Derrida and Bernard-Henri Lévy.

(© Marc Fontanel/Gamma)

With Paul de Man, in the United States, towards the end of the 1970s.

(Derrida: personal collection)

‘The Prague Aff air’: the front page of Le Matin on 2 January 1982. At that time, the press had no decent photos of Derrida.

(private collection)

Gare de l’Est: on his return from Prague, Derrida, with his wife Marguerite on his left, replies to journalists’ questions.

(© Joël Robine/AFP)

Travelling in Cotonou towards the end of the 1970s.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Conference on ‘The Ends of Man’, Cerisy, 1980. From left to right, on either side of Derrida: Jean-Michel Rey, Sarah Kofman, and Daniel Limon.

(© Archives de Pontigny-Cerisy)

With Jorge Luis Borges, in 1985.

(Derrida: personal collection)

In Dublin, next to the statue of James Joyce.

(Derrida: personal collection)

In Heidelberg, in 1988, with Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Hans-Georg Gadamer.

(Derrida: personal collection)

With François Châtelet and Pierre Bourdieu.

(Derrida: personal collection)

At Laguna Beach, California.

(Derrida: personal collection)

With Geoff rey Bennington, at the time of writing ‘Circumfession’.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Visiting Louis Althusser at the clinic of Soisy-sur-Seine.

(© Fonds Jacques Derrida/IMEC)

Serving the tea. Hôtel Saint-Georges, Algiers, 1984.

(Derrida: personal collection)

In Beijing, in September 2001.

(Derrida: personal collection)

1991, the photographer Carlos Freire followed Jacques Derrida in his day-to-day life: above, at his seminar at the École des Hautes Études en sciences sociales.

(© Carlos Freire)

At the café. (© Carlos Freire)

In his offi ce in Ris-Orangis. (© Carlos Freire)

In the converted loft in Ris-Orangis. ‘My sublime,’ Derrida sometimes called it.

(© Carlos Freire)

With Hélène Cixous, 2003.

(© Sophie Bassouls/Sygma/Corbis)

With élisabeth Roudinesco, 2001.

(© John Foley-Opale)

Jacques and Marguerite at Cerisy.

(Derrida: personal collection)

On the beach at Villefranche-sur-Mer, with his brother René and his sister Janine.

(Derrida: personal collection)

Part of Jacques Derrida’s last library at Ris-Orangis.

(© Andrew Bush)

At Cerisy in 1992 for the conference on ‘Crossing Frontiers’. From left to right: Marie-Louise Mallet, Jacques Derrida, Michael Levinas, and Michal Govrin. (© Archives de Pontigny-Cerisy)

With Avital Ronell, in 2003 or 2004. (Derrida: personal collection)

Cerisy-la-Salle, summer 2002. 15 July was the birthday of both Daniel Mesguich (fi rst left) and Jacques Derrida. Also visible, from left to right: René Major, édith Heurgon, and Maurice de Gandillac.

(© Archives de Pontigny-Cerisy)

In Cerisy again, conference on ‘The Democracy to Come’, with Jean-Luc Nancy, in 2002. (Derrida: personal collection)

May 2002. (© Serge Picard/Agence Vu)

Introduction

Does a philosopher have a life? Can you write a philosopher’s biography? This was the question raised, in October 1996, at a conference organized by New York University. In an improvised statement, Jacques Derrida began by saying:

As you know, traditional philosophy excludes biography, it considers biography as something external to philosophy. You’ll remember Heidegger’s reference to Aristotle: ‘What was Aristotle’s life?’ Well, the answer lay in a single sentence: ‘He was born, he thought, he died.’ And all the rest is pure anecdote.1

However, this was not Derrida’s position. Already, in a 1976 paper on Nietzsche, he had written:

We no longer consider the biography of a ‘philosopher’ as a corpus of empirical accidents that leaves both a name and a signature outside a system which would itself be offered up to an immanent philosophical reading – the only kind of reading held to be philosophically legitimate [. . .].2

Whereupon Derrida called for the invention of ‘a new problematic of the biographical in general and of the biography of philosophers in particular’, a rethinking of the borderline between ‘corpus and body [corps]’. This preoccupation never left him. In a late interview, he again insisted that ‘the question of “biography”’ did not cause him any worries – indeed, one might say that it was of great interest to him:

I am among those few people who have constantly drawn attention to this: you must (and you must do it well) put philosophers’ biographies back in the picture, and the commitments, particularly political commitments, that they sign in their own names, whether in relation to Heidegger or equally to Hegel, Freud, Nietzsche, Sartre, or Blanchot, and so on.3

Within his own works, Derrida himself was not averse, when discussing Walter Benjamin, Paul de Man, and several others, to bringing in biographical material. In Glas, for example, he frequently quotes Hegel’s correspondence, referring to his family and his financial worries, without considering these texts to be minor or extraneous to his philosophical work.

In one of the last sequences of the film on Derrida made by Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering Kofman, Derrida went even further, replying provocatively to the question of what he would like to discover from a documentary about Kant, Hegel, or Heidegger:

I’d like to hear them talk about their sexual lives. What was the sexual life of Hegel or Heidegger? [. . .] Because it’s something they don’t talk about. I’d like to hear them discuss something they don’t talk about. Why do philosophers present themselves in their works as asexual beings? Why have they effaced their private lives from their work? Why do they never talk about personal things? I’m not saying someone should make a porn film about Hegel or Heidegger. I want to hear them talking about the part love plays in their lives.

Even more significantly, autobiography – that of others, Rousseau and Nietzsche mainly, but his own too – was for Derrida a fully fledged philosophical object: both the principles underlying it and the details contained in it were worthy of consideration. In his view, autobiographical writing was even the genre, the one which had first given him a hankering to write, and never ceased to haunt him. Ever since his teens, he had been dreaming of a sort of immense journal of his life and thought, of an uninterrupted, polymorphous text – one that would be, so to speak, absolute:

Memoirs, in a form that does not correspond to what are generally called memoirs, are the general form of everything that interests me – the wild desire to preserve everything, to gather everything together in its idiom. And philosophy, or academic philosophy at any rate, for me has always been at the service of this autobiographical design of memory.4

Derrida gave us these Memoirs that are not Memoirs by disseminating them across many of his works. ‘Circumfession’, The Post Card, Monolingualism of the Other, Veils, Memoirs of the Blind, Counterpart* and many other texts, including many late interviews, as well as the two films about him, add up to an autobiography that is fragmentary but rich in concrete and sometimes quite intimate details: what he on occasion referred to as an ‘‘ autobiothanatohetero-graphical opus’. I have drawn a great deal on these invaluable notes and sketches, comparing them with other sources whenever possible.

In this book, I will not be seeking to provide an introduction to the philosophy of Jacques Derrida, let alone a new interpretation of a work whose breadth and richness will continue to defy commentators for years to come. But I would like to present the biography of a philosophy at least as much as the story of an individual. So I will mainly focus on readings and influences, the genesis of the principal works, their turbulent reception, the struggles in which Derrida was engaged, and the institutions he founded. However, this will not be an intellectual biography. I find this label irritating for several reasons; mainly the exclusions it seems to involve: childhood, family, love, material life. For Derrida himself – as he explained in his interviews with Maurizio Ferraris – ‘the expression “intellectual biography’” was in any case deeply problematic. Even more so, a century after the birth of psychoanalysis, was the phrase ‘conscious intellectual life’. And the boundary between public life and private life seemed just as fragile and wavering to him:

At a certain moment in the life and career of a public man, of what is called – following pretty hazy criteria – a public man, any private archive, supposing that this isn’t a contradiction in terms, is destined to become a public archive if it isn’t immediately burned (and even then, on condition that, once burned, it does not leave behind it the speaking and burning ash of various symptoms archivable by interpretation or public rumour).5

So this biography has refused to exclude anything. Writing the life of Jacques Derrida means writing the story of a Jewish boy from Algiers, excluded from school at the age of twelve, who became the French philosopher whose works have been the most widely translated throughout the world; the story of a fragile and tormented man who, to the end of his life, continued to see himself as ‘rejected’ by the French university system. It means bringing back to life such different worlds as pre-independence Algeria, the microcosm of the École Normale Supérieure, the structuralist period, and the turbulent events of 1968 and afterwards. It means describing an exceptional series of friendships with major writers and philosophers, from Louis Althusser to Maurice Blanchot, and from Jean Genet to Hélène Cixous, by way of Emmanuel Levinas and Jean-Luc Nancy. It means going over a no less long series of polemics, waged over serious issues but often brutal in tone, with thinkers such as Claude Lévi-Strauss, Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, John R. Searle, and Jürgen Habermas, as well as several controversies that spilled over from academic circles into a wider audience, the most celebrated of them concerning Heidegger and Paul de Man. It means retracing a series of courageous political commitments in support of Nelson Mandela, illegal immigrants, and gay marriage. It means relating the fortune of a concept – deconstruction – and its extraordinary influence that went far beyond the philosophical world, affecting literary studies, architecture, law, theology, feminism, queer studies, and postcolonial studies.

In order to carry out this project, I have of course embarked on as complete as possible a reading or rereading of an oeuvre which is, as everyone knows, very prolific: eighty published works and innumerable uncollected texts and interviews. I have explored the secondary literature as much as possible. But I have relied mainly on the considerable archives that Derrida has left us, as well as on meetings with a hundred or so witnesses.

The archive was, for the author of Paper Machine, a real passion and a constant theme for reflection. But it was also a very concrete reality. As he stated on one of his last public appearances: ‘I’ve never lost or destroyed anything. Not even the little notes [. . .] that Bourdieu or Balibar used to stick on my door [. . .] I’ve got everything. The most important things and the most apparently insignificant things.’6 Derrida wanted these documents to be openly accessible. He went so far as to explain:

The great fantasy [. . .] is that all these papers, books or texts, or floppy disks, are already living after me. They are already witnesses. I’m always thinking about it – about those who will come after my death and have a look at, for example, such and such a book I read in 1953 and will ask: ‘Why did he put a tick by that, or an arrow there?’ I’m obsessed by the structure of survival [la structure survivante] of each of these bits of paper, these traces.7

The major part of these personal archives is gathered in two collections, which I have methodically explored: the Special Collection of the Langson Library at the University of California, Irvine; and the Derrida collection at the IMEC – the Institut Mémoires de l’édition Contemporaine – at the Abbaye d’Ardenne, near Caen. I’ve gradu- ally familiarized myself with a handwriting that all of Derrida’s friends knew was difficult to decipher, and I was lucky enough to be the first person to be able to measure the incredible sum of documents accumulated by Derrida throughout his life: school work, personal notebooks, manuscript versions of books, unpublished classes and seminars, the transcriptions of interviews and debates, press articles, and, of course, his correspondence.

While he scrupulously preserved the least little letter that he was sent – and was still regretting, a few months before he died, the only correspondence that he had destroyed* –, Derrida only rarely made drafts or copies of his own letters. So considerable research has been necessary to track down and consult the most significant of these exchanges: for example, those with Louis Althusser, Paul Ricoeur, Maurice Blanchot, Michel Foucault, Emmanuel Levinas, Gabriel Bounoure, Philippe Sollers, Paul de Man, Roger Laporte, Jean-Luc Nancy, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, and Sarah Kofman. Even more valuable are certain letters sent to friends of Derrida’s youth, such as Michel Monory and Lucien Bianco, during his formative years. Many others cannot be located or have been lost, such as the great number of letters sent by Derrida to his parents.

One far from negligible detail is that I embarked on this biography in the immediate aftermath of Derrida’s death, just when we had barely started to enter into ‘the return of Jacques Derrida’, to quote a phrase of Bernard Stiegler. Begun in 2007, it was published in 2010, the year when he would have been eighty. So it would have been absurd to draw only on written material when most of the philosopher’s associates were potentially accessible.

The trust placed in me by Marguerite Derrida has been exceptional. She has allowed me access to the full set of archives, but has also granted me several interviews. Meetings, often long and sometimes repeated, with witnesses from every period have been essential. I have been lucky enough to talk to Derrida’s brother, sister, and favourite cousin, as well as many fellow-students and companions of his youth, who shed light on what he once described as a thirty-two-year-long adolescence. I was able to question a hundred or so of his associates: friends, colleagues, publishers, students, and even some of his detractors. But I have not, of course, managed to make contact with all the potential witnesses, and some did not wish to meet with me. A biography is also constructed from obstacles and refusals, or, if you prefer, resistances.

More than once, I have felt giddy at the extent and difficulty of the task on which I had embarked. It probably needed a certain naïvety, or at least ingenuousness, to get such a project off the ground. After all, Geoffrey Bennington, one of the best commentators on Derrida’s work, had sternly dismissed the possibility of a biography worthy of the name:

It is of course to be expected that Derrida will some day be the subject of biographical writing, and there is nothing to prevent this being of the most traditional kind [. . .]. But this type of complacent and recuperative writing would at some point have to encounter the fact that Derrida’s work should at least have disturbed its presuppositions. I would hazard a guess that one of the last genres of academic or quasi-academic writing to be affected by deconstruction is the genre of biography. [. . .] Is it possible to conceive of a multiple, layered but not hierarchised, fractal biography which would escape the totalising and tele-ological commitments which inhabit the genre from the start?8

Without denying the interest of such an approach, I have sought, in the final analysis, to write not so much a Derridean biography as a biography of Derrida. Mimicry, in this respect as in many others, does not seem the best way of serving him today.

The faithfulness that counted for me was of another kind. Derrida had accompanied me, beneath the surface, ever since I first read OfGrammatology, in 1974.1 got to know him a little, ten years later, when he wrote a generous piece on Right of Inspection, a photo album that I produced with Marie-Françoise Plissart. We exchanged letters and books. I never stopped reading him. And now, for three years, he has occupied the best part of my time and has even slipped into my dreams, in a sort of collaboration in absentia*

Writing a biography means living through an intimate and sometimes intimidating adventure. Whatever happens, Jacques Derrida will now be part of my own life, like a sort of posthumous friend. A strange, one-way friendship that he would not have failed to question. I am convinced of one thing: there are biographies only of the dead. So every biography is lacking its supreme reader: the one who is no longer there. If there is an ethics of biographers, it can perhaps be located here: would they dare to stand, book in hand, in front of their subject?

_________________

* In most cases, especially for his first works, Derrida preferred to go against common use and avoid capital letters in the French titles of his books. ‘I agree – L’écriture et la différence [ Writing and difference]’, Philippe Sollers wrote to him in a 1967 pre-publication letter. [Sollers’ point is that the French title would more usually be L’écriture et la différence. Derrida’s – inconsistent – practice cannot always be followed in the English translations, nor of course, a fortiori, in German. – Tr.]

* ‘I once destroyed a correspondence. With grim determination: I crushed it – it didn’t work; burned it – it didn’t work ... I destroyed a correspondence that I should not have destroyed and I will regret it all my life’ (Rue Descartes no. 52, 2006, p. 96). There are several indications that this destruction occurred at the end of the 1960s or the beginning of the 1970s.

* Readers curious to know more about how this book was written, and the problems the author encountered, can refer to Trois ans avec Derrida: les carnets d’un biographe (Paris: Flammarion, 2010).

PART I

Jackie

1930–1962

1The Negus

1930–1942

For a long time, Derrida’s readers knew nothing of his childhood or youth. At most, they might be aware of the year he was born, 1930, and the place, El Biar, on the outskirts of Algiers. Admittedly, there are several autobiographical allusions in Glas and even more in The Post Card, but they are so woven into various textual games that they remain uncertain and, as it were, undecidable.

Only in 1983, in an interview with Catherine David for Le Nouvel Observateur, did Derrida finally agree to proffer a few factual details. He did so in an ironic, vaguely tetchy way, somewhat telegraphic in style, as if in a hurry to get shot of these impossible questions:

You mentioned Algeria just now. That is where it all began for you.

Ah, you want me to say things like ‘I-was-born-in-El Biar-on-the-outskirts-of-Algiers-in-a-petty-bourgeois-family-of-assimi-lated-Jews-but. . .’ Is that really necessary? I can’t do it. You’ll have to help me . . .

What was your father’s name?

Ok, here we go. He had five names, all the names of the family are encrypted, along with a few others, in The Post Card, sometimes unreadable even for those who bear these names; often they’re not capitalized, as one might do for ‘aimé’ or ‘rené’ . . .*

How old were you when you left Algeria?

You really are persistent. I came to France at the age of nineteen. I had never left El Biar before. The 1940 war in Algeria, in other words the first underground rumblings of the Algerian war.1

In 1986, in a dialogue with Didier Cahen broadcast on France-Culture (‘Le bon plaisir de Jacques Derrida’), he restated his previous objections, while acknowledging that writing would doubtless enable him to tackle these questions:

I wish that a narration were possible. Right now, it’s not. I dream, not of managing, one day, to recount this legacy, this past experience, this history, but at least of giving a narrative account of it among other possible accounts. But, in order to get there, I’d have to undertake a particular kind of work, I’d have to set out on an adventure that up until now I’ve not managed. To invent, to invent a language, to invent modes of anamnesis . . . . 2

Derrida’s references to his childhood gradually became less reluctant. In Ulysses Gramophone (first French edition published in 1987), he mentioned his secret forename, Élie,* the name that was given to him on the seventh day of his life; in Memoirs of the Blind, three years later, he described his ‘wounded jealousy’ of the talent for drawing that his family recognized in his brother René.

The year 1991 was a turning-point, with the volume Jacques Derrida coming out in the series ‘Les Contemporains’, published by Éditions du Seuil: not only was Jacques Derrida’s contribution, ‘Circumfession’, autobiographical from beginning to end, but in the ‘Curriculum vitae’ that followed Geoffrey Bennington’s analysis, the philosopher agreed to submit to what he called ‘the law of genre’, even if he did so with an enthusiasm that his co-author described, delicately, as ‘uneven’.3 But childhood and youth were by far the most heavily emphasized parts of his life, at least as regards any personal reflections.

Thereafter, autobiographical references in Derrida’s written work became increasingly frequent. As he acknowledged in 1998: ‘Over the last couple of decades [. . .], in a way that is both fictitious and not fictitious, first-person texts have become more common: personal records, confessions, reflections on the possibility or impossibility of confession.’4 As soon as we start to fit these fragments together, they provide us with a remarkably precise narrative, albeit one that is both repetitive and full of gaps. They constitute a priceless source – the main source for that period, and the only source that enables us to describe Derrida’s childhood empathetically, as if from within. But these first-person narratives, of course, need to be read, first and foremost, as texts. They should be approached as cautiously as the Confessions of Saint Augustine or Rousseau. And in any case, as Derrida acknowledges, they are belated reconstructions, both fragile and uncertain: ‘I try to recall, through documented facts and subjective pointers, what I might have thought or felt at that time, but, more often than not, these attempts fail.’5

The material traces that can be added to, and compared with, this wealth of autobiographical material are, unfortunately, few and far between. Many of the family papers seem to have disappeared in 1962, when Derrida’s parents left El Biar in some haste. I have not found a single letter from the Algerian period. And, in spite of my efforts, I have not been able to locate even the least document from the schools that Derrida attended. But I have been lucky enough to have access to four valuable witnesses from those distant years: René and Janine Derrida – Jackie’s older brother and his sister – and his cousin Micheline Lévy, as well as Fernand Acharrok, one of his closest friends from that period.

In 1930, the year of Derrida’s birth, Algeria celebrated in great pomp the centenary of its conquest by the French. During his visit there, French President Gaston Doumergue made a point of lauding ‘the admirable work of colonization and civilization’ that had been carried out over the previous century. This was seen, by many people, as the high point of French Algeria. The following year, in the Bois de Vincennes, the Colonial Exhibition received thirty-three million visitors, whereas the anti-colonial exhibition organized by the Surrealists met with the most modest of successes.

With its 300,000 inhabitants, its cathedral, its museum, and its broad avenues, Algiers, the ‘white city’ (‘Alger la Blanche’), was a kind of display window for France in Africa. Everything in it was deliberately reminiscent of the cities of metropolitan France, starting with the street names: there was the avenue Georges-Clemenceau, the boulevard Gallieni, the rue Michelet, the place Jean-Mermoz, and so on. The ‘Muslims’ or ‘natives’ – as the Arabs were generally called – were slightly outnumbered by the ‘Europeans’. The Algeria in which Jackie would grow up was a profoundly unequal society, as regards both political rights and standards of living. Communities coexisted but barely mingled – in particular, there were few mixed marriages.

Like many Jewish families, the Derridas had come over from Spain long before the French conquest of Algeria. Right from the start of colonization, the Jews had been considered by the French forces of occupation as useful people, potential allies – and this distanced them from the Muslims with whom they had hitherto lived. Another event separated them even more markedly: on 24 October 1870, French minister Adolphe Crémieux gave his name to the decree granting French citizenship, en bloc, to the 35,000 Jews living in Algeria. This did not stop anti-Semitism from breaking out in Algeria after 1897. The following year, Édouard Drumont, the notorious author of Jewish France, was elected as député for Algiers.6

One of the consequences of the Crémieux Decree was an increase in the level of assimilation of Jews into French life. Of course, Jewish religious traditions were maintained, but in a purely private space. Jewish forenames were Gallicized or, as in the Derrida family, relegated to a discreet second place. People referred to the ‘temple’ rather than the ‘synagogue’, to ‘communion’ rather than ‘bar-mitzvah’. Derrida himself, much more attentive to historical questions than is often thought, was keenly aware of this change:

I was part of an extraordinary transformation of French Judaism in Algeria: my great grandparents were still very close to the Arabs in language and customs. At the end of the nineteenth century, in the years following the Crémieux decree of 1870, the next generation became more bourgeois: though my [maternal] grandmother had to be married almost clandestinely in the back courtyard of a town hall in Algiers because of the pogroms (this was right in the middle of the Dreyfus Affair), she was already raising her daughters like bourgeois Parisian girls (16th Arrondissement good manners, piano lessons, and so on). Then came my parents’ generation: few intellectuals, mostly shopkeepers, some of modest means and some not, some who were already exploiting a colonial situation by becoming the exclusive representatives of major metropolitan brands.7

Derrida’s father, Haïm Aaron Prosper Charles, was called Aimé; he was born in Algiers on 26 September 1896. When he was twelve, he was apprenticed to the wine and spirits company Tachet; he was to work there all his life, as had his own father, Abraham Derrida, and as Albert Camus’s father had done – he too was employed in a wine-shipping business in Algiers harbour. Between the wars, wine was the main source of revenue for Algeria, and its vineyards were the fourth biggest in the world.

On 31 October 1923, Aimé married Georgette Sultana Esther Safar, born on 23 July 1901, the daughter of Moïse Safar (1870–1943) and Fortunée Temime (1880–1961). Their first child, René Abraham, was born in 1925. A second son, Paul Moïse, died when he was three months old, on 4 September 1929, less than a year before the birth of Jacques Derrida. This would make of him, he later wrote in ‘Circumfession’, ‘a precious but so vulnerable intruder, one mortal too many, Élie loved [aimé] in the place of another’.8

Jackie was born at daybreak, on 15 July 1930, at El Biar, in the hilly suburbs of Algiers, in a holiday home. Right up until the last minute, his mother refused to break off a poker game: poker would remain her lifelong passion. The boy’s main forename was probably chosen because of Jackie Coogan, who had the star role in The Kid. When he was circumcised, he was given a second forename, Élie, which was not entered on his birth certificate, unlike the equivalent names of his brother and sister.

Until 1934, the family lived in town, except during the summer months. They lived in the rue Saint-Augustin, which might seem like too much of a coincidence given the importance that the saintly author of the Confessions would have in Derrida’s work. He later retained only the vaguest images of this first home, where his parents lived for nine years: ‘a dark hallway, a grocer’s down from the house’.9

Shortly before the birth of a new child, the Derridas moved to El Biar – in Arabic, ‘the well’ – quite an affluent suburb where the children could breathe more freely. The parents plunged themselves into debt for many years when they bought their modest villa, 13, rue d’Aurelle-de-Paladines. It was located ‘on the edge of an Arab district and a Catholic cemetery, at the end of the chemin du Repos’, and came with a garden that Derrida would refer to later as the Orchard, the Pardes or PaRDeS, as he liked to write it, an image of Paradise and of the Day of Atonement (‘Grand Pardon’), and an essential place in kabbalistic tradition.

The birth of Derrida’s sister Janine gave rise to an anecdote that was constantly being retold in the family, the ‘first words’ of his that have come down to us. When his grandparents beckoned him into the bedroom, they showed him a travelling bag that probably contained the basic implements used in deliveries in those days, and told him that his little sister had just come out of it. Jackie went up to the cot and stared at the baby before declaring, ‘I want her to be put back in her bag.’

At the age of five or six, Jackie was a very charming lad. With a little boater on his head, he would sing Maurice Chevalier songs at family parties; he was often nicknamed ‘the Negus’ as his skin was so dark. Throughout his early childhood, the relation between Jackie and his mother was particularly intense. Georgette, who had been left with a childminder until she was three, was neither very affectionate nor very demonstrative towards her children. This did not stop Jackie from completely worshipping her, almost like the young Narrator of À la Recherche du temps perdu. Derrida later described himself as ‘the child whom the grown-ups amused themselves by making cry for nothing’, the child ‘who up until puberty cried out “Mummy I’m scared” every night until they let him sleep on a divan near his parents’.10 When he was sent to school, he stood in the schoolyard in tears, his face pressed against the railings.

I vividly remember being really upset, upset at being separated from my family, from my mother, my tears, my yells at nursery school, I can still see the teacher telling me, ‘Your mother’s coming to fetch you,’ and I’d ask, ‘Where is she?’ and she’d tell me, ‘She’s doing the cooking,’ and I imagined that in this nursery school [. . .], there was a place where my mother was doing the cooking. I can remember crying and yelling when I went in, and laughing when I came out. [. . .] I went so far as to make up illnesses to get me off school, I kept asking them to take my temperature.11

The future author of ‘Tympan’ and The Ear of the Other mainly suffered from repeated attacks of earache, which aroused considerable anxiety in his family. He was taken from one doctor to another. Treatment at the time was aggressive: rubber syringes filled with warm water that pierced the eardrum. On one occasion, there was even talk of removing his mastoid bone, a very painful but in those days quite common operation.

A much more serious and dramatic event occurred during this period: Derrida’s cousin Jean-Pierre, who was a year older, was run over by a car and killed, outside his home in Saint-Raphaël. The shock was made even worse by the fact that, at school, Jackie was at first wrongly told that it was his brother René who had just died. He would always be scarred by this first bereavement. One day, he would tell his cousin Micheline Lévy that it had taken him years to understand why he had wanted to call his two sons Pierre and Jean.

At primary school, Jackie was a very good pupil, except when it came to his handwriting, which was deemed impossible to read, and would remain so. ‘At break, the teacher, who knew that I was top of the class, would tell me, “Go back and rewrite this, it’s illegible; when you go to the lycée you’ll be able to get away with writing like this; but it’s not acceptable now.’”12

In this school, doubtless like many others in Algeria, racial problems were already very much to the fore: there was a great deal of brutality among the pupils. Still very timid, Jackie viewed school as hell – he felt so exposed there. Every day, he was afraid that the fights would get worse. ‘There was racist, racial violence, which spread out all over the place, anti-Arab racism, anti-Semitic, anti-Italian, anti-Spanish racism . . . All sorts! All forms of racism could be encountered . . . .,’13

There were many ‘native’ youngsters at primary school, but they tended to disappear when it was time to enter the lycée. Derrida would describe the situation in Monolingualism of the Other; Arabic was considered to be a foreign language, and while it was possible to learn it, this was never encouraged. As for the reality of life in Algeria, it was kept completely out of the picture: the history of France taught to pupils was ‘an incredible discipline, a fable and a bible, yet a doctrine of indoctrination almost ineffaceable’. Not a word was said about Algeria, nothing about its history or its geography, whereas the children were required to be able to ‘draw the coast of Brittany and the Gironde estuary with our eyes closed’ and to recite by heart ‘the names of all the major towns of all the French departments’.14

However, with ‘Le Métropole’, as France had officially to be called, pupils had a relationship that was ambivalent at best. A few of the privileged ones went there on holiday, often to spa towns such as Évian, Vittel, or Contrexéville. For all the rest, including the Derrida children, France – at once close and faraway, on the other shore of a sea too deep and wide ever to be crossed – appeared like a dream country. It was ‘the model of good speech and good writing’. It appeared less as a native country than as an ‘Elsewhere’, both ‘a strong fortress and an entirely other place’. As for Algeria, they felt they knew it ‘by way of an obscure but certain form of knowledge’; it was something other than one province among others. ‘Right from childhood, Algeria was, for us, also a country [. . .].’15

The Jewish religion played a rather low-key part in the Derridas’ family life. On high days and holidays, the children were taken to the synagogue in Algiers; Jackie was particularly affected by Sephardic music and singing, a taste that would stay with him throughout his life. In one of his last texts, he would also remember the rites involving light in El Biar, starting on a Friday evening. ‘I see again the moment when, all care having been taken, my mother having lit the lamp, la veilleuse, whose small flame floated on the surface of a cup of oil, one was suddenly no longer allowed to touch fire, to strike matches, especially to smoke, or even to let one’s finger touch a light switch.’ He would also remember joyful images of Purim with the ‘candles planted into tangerines, almond guenégueletes, white flatcakes full of holes and covered with icing sugar after having been dipped in syrup then hung like laundry over a cord’.16

In the family, it was Moïse Safar, the maternal grandfather, who, although not a rabbi, incarnated the religious consciousness: ‘a venerable righteousness placed him above the priest’.17 Austere in manners, and very observant, he would stay seated in his armchair, absorbed for hour after hour in his prayer book. It was he who, shortly before his death, at Jackie’s bar-mitzvah, gave him the pure white tallith that he would evoke at length in Veils – the prayer shawl that he later said he liked to ‘touch’ or ‘caress’ every day.18

The maternal grandmother, Fortunée Safar, outlived her husband by many years. She was the dominant figure in the family: no decision of any importance could be taken without her being consulted; she stayed for long periods in the rue d’Aurelle-de-Paladines with the Derridas. On Sundays, and during the summer months, the house was filled to overflowing with people. It was the rallying-point for the five Safar daughters. Georgette, Jackie’s mother, was the third: she was famed for her bursts of uncontrollable laughter and for her flirtatiousness. And even more for her passion for poker. Most of the time, she kept a kitty with her mother, which enabled them to balance out losses and gains. Jackie himself later told how he had been able to play poker long before he learned to read; he was capable at an early age of dealing the cards with the dexterity of a casino croupier. He liked nothing better than to stay sitting among his aunts, delighting in their silly gossip before passing it on to his male and female cousins.

Georgette loved having guests, and she could also occasionally whip up a delicious couscous with herbs, but she did not much bother her head over everyday practicalities. During the week, the shopping was delivered from the nearby grocer’s. And on Sunday mornings, it was Georgette’s husband whose job it was to go to the market, sometimes in the company of Janine or Jackie. Aimé Derrida was a rather taciturn man, without much authority, who hardly ever protested against the power of the matriarchs. ‘It’s Hotel Patch here,’ he would sometimes say, mysteriously, when the women dolled themselves up a bit too much for his taste. What he liked doing was to attend the horse races on certain Sunday afternoons, while the family would go down to one of the beautiful fine sandy beaches – often the one at Saint-Eugène called the Plage de la Poudrière.19

War had been declared, though as yet without much impact on Algerian territory, when tragedy struck the Derrida family. Jackie’s young brother Norbert, who had just turned two, was laid low by tubercular meningitis. Aimé did everything in his power to save him, consulting several doctors, but the child died on 26 March 1940. For Jackie, then nine years old, this was the ‘source of an unflagging astonishment’ in the face of what he would never be able to understand or accept: ‘to continue or resume living after the death of a loved one’. ‘I remember the day I saw my father, in 1940, in the garden, lighting a cigarette one week after the death of my little brother Norbert: “But how can he still do that? Only a week ago he was sobbing!” I never got over it.’20

For several years, anti-Semitism had flourished in Algeria more than in any region in metropolitan France. The extreme right campaigned for the Crémieux Decree to be abolished, while the headlines in the Petit Oranais repeated day after day: ‘We need to subject the synagogues and Jewish schools to sulphur, pitch, and if possible the fires of hell, to destroy the Jews’ houses, seize their capital and drive them out into the fields like rabid dogs.’21 And so, shortly after the crushing defeat of the French Army by the Germans, the ‘National Revolution’ called for by Marshal Pétain found more than favourable ground in Algeria. In the absence of any German occupation, local leaders showed considerable zeal: to satisfy anti-Jewish sentiment, anti-Semitic measures were applied more quickly and thoroughly than in metropolitan France.

The law of 3 October 1940 forbade Jews from practising a certain number of jobs, especially in public service. A numerus clausus of 2 per cent was established for the liberal professions; the following year, this measure would be made even stricter. On 7 October, the Minister of the Interior, Peyrouton, repealed the Crémieux Decree. For this entire population, which had been French for seventy years, the measures passed by the Vichy Government constituted ‘a terrible surprise, an unexpected catastrophe’. ‘It was an “inner” exile, expulsion from French citizenship, a drama that turned the daily lives of the Jews of Algeria upside down.’22

Even though he was only ten, Jackie too suffered the consequences of these hateful measures:

I was a good pupil at primary school, more often than not top of the class, which allowed me to note the changes that resulted from the Occupation and the rise to power of Marshal Pétain. In the schools of Algeria, where there were no Germans, they started getting us to send letters to Marshal Pétain, to chant ‘Marshal, here we are!’, etc., to raise the flag every morning at the start of class, and they always asked the top of the class to raise the flag, but when it was my turn, they replaced me by someone else. [. . .] I can’t make out, now, whether I was hurt by this intensely, dimly, or vaguely.23

Anti-Semitic insults were henceforth authorized, if not encouraged, and they erupted at every moment, especially among the children.

As for the word Jew, I do not believe I heard it first in my family [. . .]. I believe I heard it at school in El Biar, already charged with what, in Latin, one would call an insult [injure], injuria, in English, injury, both an insult, a wound, and an injustice [. . .]. Before understanding any of it, I received this word like a blow, a denunciation, a de-legitimation prior to any legality.24

The situation rapidly deteriorated. On 30 September 1941, following the visit to Algeria of Xavier Vallat, the General Commissioner for Jewish Affairs, a new law established a numerus clausus of 14 per cent for Jewish children in primary and secondary education, a measure that had no equivalent in metropolitan France. In November 1941, the name of Jacques’s brother René appeared on the list of excluded pupils: he would lose out on two years of study, and thought he might stop going to school for good, as did several of his friends. His sister Janine, aged just seven, was also expelled from her school.

As for Jackie, he entered the first form of the lycée at Ben Aknoun, a former monastery very close to El Biar. Here he met Fernand Acharrok and Jean Taousson, who would be the main friends of his teenage years. But if this first year at high school was important, this was above all because it coincided for Jackie with a real discovery: that of literature. He had grown up in a house where there were few books, and had already exhausted the modest resources of the family library. That year, his French teacher was a certain M. Lefèvre.* He was a young, red-headed man who had just arrived from France. He talked to his pupils with an enthusiasm that sometimes made them smile. But one day, he started singing the praises of being in love, and mentioned The Fruits of the Earth by André Gide. Jackie immediately got hold of a copy of this work and was soon ecstatically immersed in it. He would read and re-read it for years on end.

I would have learned this book by heart if I could have. No doubt, like every adolescent, I admired its fervour, the lyricism of its declarations of war on religion and families [. . .]. For me it was a manifesto or a Bible [. . .] sensualist, immoralist, and especially very Algerian. [. . .] I remember the hymn to the Sahel, to Blida, and to the fruits of the Jardin d’Essai.25

A few months later, it was another – and altogether less desirable – face of France that he would be forced to confront.

_________________

* As we discover in the following pages, ‘Aimé’ and ‘René’ (with capitals) were the proper names of members of Derrida’s family, but when used in lower case are adjectives (‘beloved’ and ‘reborn’). – Tr.

* The French equivalent of English ‘Elijah’ (and also ‘Elias’). – Tr.

* According to Fernand Acharrok, this teacher’s name was actually M. Verdier.

2Under the Sun of Algiers

1942–1949

Entry into adolescence happened all of a sudden, one October morning in 1942. On the first day of the new school year, the surveillant général of the Lycée Ben Aknoun called Jackie into his office and told him: ‘You are going to go home, my little friend, your parents will get a note.’1 The percentage of Jews admitted into Algerian classes had just been lowered from 14 per cent to 7 per cent: yet again, the authorities had outstripped Vichy in their zeal.2 As Derrida would often say, this exclusion was ‘one of the earthquakes’ in his life:

I wasn’t expecting it in the least and I just couldn’t understand it. I am striving to remember what must have been going through me at the time, but in vain. It has to be said that, even in my family, nobody explained to me why this was the situation. I think it remained incomprehensible for many Jews in Algeria, especially as there weren’t any Germans; these initiatives came from French policy in Algeria, which was more severe than in France: all the Jewish teachers in Algeria were expelled from their schools. For this Jewish community, things remained enigmatic, perhaps not accepted, but suffered like a natural catastrophe for which there is no explanation.3

Even if he refused to exaggerate the seriousness of the experience, which would be ‘offensive’ given the persecutions suffered by European Jews, Derrida acknowledged that this trauma left its mark on him at the deepest level, and contributed to making him the person he was. He wished to erase nothing from his memory, so how could he have forgotten that morning in 1942 when ‘a little black and very Arab Jew’4 was expelled from the Lycée Ben Aknoun?

Beyond any anonymous ‘administrative’ measure, which I didn’t understand at all and which no one explained to me, the wound was of another order, and it never healed: the daily insults from the children, my classmates, the kids in the street, and sometimes threats or blows aimed at the ‘dirty Jew,’ which, I might say, I came to see in myself.5

In the weeks immediately following this hardening of anti-Semitic measures, the war took a major turn in Algeria. On the night of 7–8 November 1942, American troops landed in North Africa. In Algiers, fierce fighting broke out between the Vichy forces, who did not hesitate to shoot at the Allies, and groups of resistance fighters led by José Aboulker, a twenty-two-year-old medical student. Derrida gave a detailed account of that day to Hélène Cixous:

At dawn, we started to hear gunfire. There was an official resistance on the French side, there were French gendarmes, French soldiers who pretended to be going off to fight the English and Americans coming in from Sidi Ferruch. [. . .] And then, in the afternoon, we saw soldiers deploying outside our house [. . .] with helmets like we’d never seen. They weren’t French helmets. We said to ourselves: they’re Germans. And they were Americans. We’d never seen American helmets, either. And that same evening, the Americans arrived in force, as always handing out cigarettes, chewing gum, chocolates [. . .]. This first disembarkation was like a caesura, a break in life, a new point of arrival and departure.6

This was also a turning point in the Second World War. In metropolitan France, the southern, so-called ‘free’ zone was invaded on 11 November by the Wehrmacht and became an ‘operational’ zone. As for the city of Algiers, which had hitherto been preserved from the direct effects of war, it was subjected to over a hundred bombing raids, which caused many deaths. The view from the hills of El Biar was terrifying: the sea and the city were lit up by the guns of the navy, while the sky was crisscrossed by searchlights and ack-ack fire. For several months, the sirens wailed and there was a stampede to the shelters almost every day. Jackie would never forget the panic that seized him one evening when, as so often, the family had taken shelter in a neighbour’s home: ‘I was exactly twelve, my knees started to tremble uncontrollably.’7

Shortly after being expelled from the Lycée Ben Aknoun, Jackie was enrolled at the Lycée Maïmonide, also known as Émile-Maupas, from the name of the street on which it was located, on the edge of the Casbah. This improvised lycée had been opened the previous spring by Jewish teachers driven out of their jobs in state education. While his exclusion from Ben Aknoun had deeply wounded Jackie, he balked almost as much at what he perceived as a ‘group identification’. He hated this Jewish school right from the start, and ‘skived off as often as he could. The general chaos and the difficulties of everyday life were so great that his parents seem never to have been informed of his absences. Of the few days he did actually spend at Émile-Maupas, Derrida kept a memory that he described in his dialogues with Élisabeth Roudinesco: