92,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

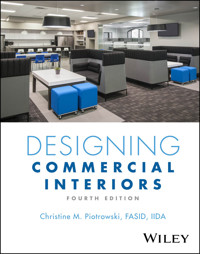

Practical, comprehensive resource for commercial interior design, covering research, execution, safety, sustainability, and legal considerations

Designing Commercial Interiors explores the entire design process of commercial projects from planning to execution to teach the vital considerations that will make each project a success. This book delivers a solid understanding of the myriad factors in play throughout designing restaurants, offices, lodging, retail and healthcare facilities.

Updates to the newly revised Fourth Edition include changes to office space design to promote flexibility, post-pandemic considerations for work and interior design, the latest industry certification requirements, sustainable design considerations. and safety/legal codes. Updated supplemental instructor’s resources, including a revised instructor’s manual with sample test questions and exercises are available on the companion website. A list of terms fundamental to each chapter has also been added at the end of each chapter.

Other topics covered in Designing Commercial Interiors include:

- A thorough review of relevant design and research skills and methods

- How the global marketplace shapes designers’ business activities

- Product specification principles, WELL, and LEED certification and credentials

- Accessible design in facilities, elements of evidence-based design, and adaptive reuse

- Project manager responsibilities, working with stakeholders, and special considerations for executive-level clients

- Project delivery methods, including design-bid-build, design-build, and integrated design

Designing Commercial Interiors is an authoritative and complete reference on the subject for university and community college students in programs related to interior design and those preparing for the NCIDQ exam. The text is also valuable as a general reference for interior designers less familiar with commercial interior design.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1212

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Disclaimer

Preface

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER 1: Commercial Interior Design

Historical Overview

Understanding the Client’s Business

Working in Commercial Interior Design

Where the Jobs Are

Professionalism

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

CHAPTER 2: Forces that Shape Commercial Interior Design

Cultural Sensitivity

Global Marketplace

Sustainable Design

Security and Safety

Codes

Accessible Design

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

Note

CHAPTER 3: Research in Interior Design

Research Methodologies in Design

Evidence-Based Design

Problem Solving in Design

Project Goals and Concept Development

Design Process

Programming Elements

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

Note

CHAPTER 4: Project Management

What Is Project Management?

Role and Responsibilities of the Project Manager

Working Relationships with Stakeholders and Team Members

Project Delivery Methods

Building Information Modeling (BIM)

Project Process

Adaptive Reuse

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

CHAPTER 5: The Office

Historical Overview

Issues Impacting Office Design

An Overview of Office Operations

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

CHAPTER 6: Office Interior Design Elements

Types of Office Spaces

Planning and Design Elements

Design Applications

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

Notes

CHAPTER 7: Lodging Facilities

Historical Overview

Overview of Lodging Business Operations

Types of Lodging Facilities

The Changing Lodging Guest

Planning and Interior Design Elements

Design Applications

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

CHAPTER 8: Food and Beverage Facilities

Historical Overview

Overview of Food and Beverage Business Operations

Types of Food and Beverage Facilities

Planning and Interior Design Elements

Design Applications

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

Note

CHAPTER 9: Retail Facilities

Historical Overview

Overview of Retail Business Operations

Types of Retail Facilities

Planning and Interior Design Elements

Design Applications

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

CHAPTER 10: Healthcare Facilities

Historical Overview

Overview of Healthcare/Medicine

Types of Healthcare Facilities

Planning and Interior Design Elements

Design Applications

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

Notes

CHAPTER 11: Senior Living Facilities

Historical Overview

Overview of Senior Living Facilities

Types of Senior Living Facilities

Planning and Interior Design Elements

Design Applications

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

Note

CHAPTER 12: Recreational Facilities

Overview

Types of Recreational Facilities

Fitness Center

Day Spas

Golf Clubhouses

Auditoriums

Key Terms

Bibliography and References

Appendix

Trade Associations

Periodicals

Glossary

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

Chapter 1

Table 1-1 Common Specialties in Commercial Interior Design

Chapter 4

Table 4-1 Sample Milestone Chart

Chapter 6

Table 6-1 Area Ranges for Support Spaces

Table 6-2 Office Lighting Levels

Chapter 7

Table 7-1 Common Lodging Facilities

Table 7-2 Guest Space for Different Types of Lodging Properties

Table 7-3 Typical Space Allowances for Guest Rooms

Chapter 8

Table 8-1 Space Estimates for Kitchen Functional Areas

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1-1 High-limit area. Casino at the Venetian Resort, Macao.

Figure 1-2 Employee lunch areas are often places for teamwork and collaborat...

Figure 1-3 Millwork drawings are one type of design document that is commonl...

Chapter 2

Figure 2-1 Gifts of the Raven gift shop. Vancouver, Canada.

Figure 2-2 Grand Lobby, the Palm Resort, Atlantis, Dubai.

Figure 2-3 Sustainable materials were used in the design of this restaurant ...

Figure 2-4 Accessible single-user unisex restroom showing plan when door swi...

Figure 2-5 Accessible toilet facilities for multiple users. Plan example sho...

Chapter 3

Figure 3-1 Conceptual floor plan for a law office. Plan shows proposed locat...

Figure 3-2 Schematic sketches are used to graphically explain design concept...

Chapter 4

Figure 4-1 Refurbishment projects require careful attention to detail. This ...

Figure 4-2 Sample floor plan for a professional office, showing partitions a...

Figure 4-3 Demolition and construction plan for the project shown in Figure ...

Figure 4-4 Sample bar or Gantt chart.

Figure 4-5 Sample CPM diagram.

Figure 4-6 Alaskan Neurology Center sleep lab. A major renovation of a books...

Figure 4-7 Alaskan Neurology Center MRI suite; an adaptive reuse project....

Chapter 5

Figure 5-1 Quickborner office landscape project depicting the layout of the ...

Figure 5-2 Action Office workstation from the 1960s with the use of panels a...

Figure 5-3 Floor plan indicates closed office stations, as well as collabora...

Figure 5-4 Collaborative work areas in a corporate office facility.

Figure 5-5 A sample corporate organizational chart.

Figure 5-6 Traditional executive offices are large and include more seating ...

Figure 5-7 The Redwood Trust’s office workstations are designed to provide a...

Figure 5-8 Reception area for Steelcase Worklife Center, New York City. The ...

Figure 5-9 The reception area for a small corporate office facility helps to...

Chapter 6

Figure 6-1 Floor plan of a corporate office group. Plan shows integration of...

Figure 6-2 This project refurbished a commercial laundry facility into graph...

Figure 6-3 Private office for an upper-management employee that was designed...

Figure 6-4 Floor plans representing typical furniture layouts for various jo...

Figure 6-5 Modified open plan using open office products that create various...

Figure 6-6 Systems furniture floor plan indicating angled circulation paths....

Figure 6-7 Typical case goods office furniture. Sizes noted in figure are th...

Figure 6-8 Typical file cabinet units (vertical files on left; lateral files...

Figure 6-9 Typical office seating units in traditional and contemporary styl...

Figure 6-10 The Aeron chair is a popular ergonomic–style office chair. It is...

Figure 6-11 Product specification using open-plan systems furniture with a c...

Figure 6-12 Action office is one of the original open plan products. It reta...

Figure 6-13 Office designed using a frame and tile product.

Figure 6-14 Floor plan showing a variety of uses for workstations and compon...

Figure 6-15 Plans of two managers’ offices showing savings in square footage...

Figure 6-16 Methods of connecting electrical service to open office panel sy...

Figure 6-17 Professional office with systems furniture and conventional clos...

Figure 6-18 Entry lobby for luluemon athletica. Note the textural difference...

Figure 6-19 Entry lobby for a small accounting office. This office for W.H. ...

Figure 6-20 Floor plan showing the executive office suite.

Figure 6-21 Florida Business Interiors conference room. Boardrooms are desig...

Figure 6-22 Executive office highlighted with a custom-designed desk.

Figure 6-23 Floor plan shows many types of conferencing arrangements.

Figure 6-24 Employee break room.

Figure 6-25 Collaboration takes place in many areas of the office, including...

Figure 6-26 Floor plan of small professional office. Notice the mix of case ...

Figure 6-27 View of work area and private offices in a design office.

Figure 6-28 Home office highlighted by custom cabinets.

Chapter 7

Figure 7-1 The Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, Michigan.

Figure 7-2 The Ayres Fountain Valley hotel lobby was designed with the clien...

Figure 7-3 Guest master bedroom suite at Caesar’s Octavius Tower Resort.

Figure 7-4 Conference center hotel meeting room.

Figure 7-5 The upper lobby of the Lied Lodge & Conference Center in Nebraska...

Figure 7-6 Layouts of guest room configurations.

Figure 7-7 Clubhouse lobby at the Boulders Resort hotel. Notice the variety ...

Figure 7-8 Lobby space of the MGM Macau hotel showing materials features. No...

Figure 7-9 The design of the Ayres Hotel Orange lobby blends contemporary de...

Figure 7-10 Furniture floor plan of the Ayers Hotel Orange.

Figure 7-11 Floor plan of the upper-level lobby and registration, Lied Lodge...

Figure 7-12 Lobby of the InterContinental Hotel in New York City.

Figure 7-13 A guest room with two beds. This room in a sustainably designed ...

Figure 7-14 Floor plan for a common double-bed guest room.

Figure 7-15 Floor plan for a typical king-sized bed guest room.

Figure 7-16 A luxurious suite bedroom with king-sized bed in the French styl...

Figure 7-17 This floor plan shows one typical way to plan a guest room suite...

Figure 7-18 A contemporary and elegant suite at the Sofitel Nusa Dua Beach r...

Figure 7-19 Luxury suite bathroom in a French style at Caesar’s Octavius Tow...

Figure 7-20 Suite space showing eating area and bedroom area. Ritz Carlton D...

Figure 7-21 Accessible guest room floor plan. Note the required turnaround s...

Figure 7-22 Floor plan shows the prefunction corridor and common plans for t...

Figure 7-23 Spa with a view into the massage room.

Figure 7-24 Floor plan of a restaurant in a hotel showing its relationship t...

Figure 7-25 Elegant lobby bar and seating area at the JW Marriott, New Delhi...

Figure 7-26 Suite space with a winter sports theme at The Cottage Inn.

Figure 7-27 Themed guest room at The Cottage Inn.

Chapter 8

Figure 8-1 Restaurant and home bakery first constructed in the late 1800s an...

Figure 8-2 The Windows on the World Restaurant (1976–2001) was located at th...

Figure 8-3 Main dining room at the Adrift restaurant at Marina Bay Sands....

Figure 8-4 Floor plan of the Ceiba Restaurant, Washington, DC.

Figure 8-5 View of the Ceiba Restaurant, Washington, DC, showing tables set ...

Figure 8-6 A relaxing design for the Garden Café...

Figure 8-7 The Timber dining room at Lied Lodge & Conference Center.

Figure 8-8 Floor plan of the Mystic Dunes Restaurant and food facilities....

Figure 8-9 Dining room layout indicating typical traffic aisle spacing betwe...

Figure 8-10 Typical spacing when planning booth and banquette seating.

Figure 8-11 Restaurant seating area at the Decatur Country Club. The wood ch...

Figure 8-12 Floor plan of the Bai-Plu Restaurant and Sushi Bar. It is intere...

Figure 8-13 Dining room and sushi bar at Bai-Plu Restaurant and Sushi Bar. T...

Figure 8-14 A private dining room at the Ritz Carlton Dove Mountain.

Figure 8-15 Coffee shop area at Breathing Space Yoga and Fitness Center.

Figure 8-16 The bar integrated into the dining room of a restaurant at Ritz ...

Figure 8-17 Detailed drawing of a back bar and a curved bar.

Figure 8-18 Lounge at the restaurant and bar at the Adrift resort, Marina Ba...

Chapter 9

Figure 9-1 Mixed-use shopping center development.

Figure 9-2 Retail specialty store. This store uses rescued furniture items f...

Figure 9-3 Note the different kinds of shelving and display cases in this sp...

Figure 9-4 Mannequins in lifelike poses are often used to display merchandis...

Figure 9-5 Schedoni, a small retail store in Coral Gables, Florida. Lighting...

Figure 9-6 Floor plan shows functional divisions of a shop for customer area...

Figure 9-7 Floor plan using the boutique system.

Figure 9-8 A builder’s showroom displays architectural finish choices in cus...

Figure 9-9 The Something Blue bridal shop was designed in a former bank, cre...

Figure 9-10 Interior of the remodeled Mills clothing store. Note the contemp...

Figure 9-11 View into the Exploration gift store at Vancouver International ...

Figure 9-12 This is the merchandising floor plan for the Gift of the Raven g...

Figure 9-13 Jewelry stores require custom cabinets along with critical light...

Figure 9-14 Holly Hunt showroom. Notice the two different vignettes in this ...

Chapter 10

Figure 10-1 The design of this hospital lobby brings the outdoors in and cre...

Figure 10-2 The High Point Regional Cancer Center, High Point, North Carolin...

Figure 10-3 Floor plan for a small medical office suite for an endocrinologi...

Figure 10-4 Floor plan for a primary care physician.

Figure 10-5 Reception and waiting area at the Cosmetic Dermatology offices o...

Figure 10-6 Floor plan of a single practitioner family practice office.

Figure 10-7 Signage at the entrance to a large medical facility aids patient...

Figure 10-8 Family waiting area with view to outdoor garden. Yale New Haven ...

Figure 10-9 Radiology department reception area. Scottsdale Shea Medical Cen...

Figure 10-10 Floor plan for a pediatrics medical office suite.

Figure 10-11 Waiting room at Atlanta Women’s Obstetrics and Gynecology, PC....

Figure 10-12 Sample floor plan of a typical physician’s suite exam room.

Figure 10-13 Examination room in the Contra Costa Regional Ambulatory Care C...

Figure 10-14 Sample floor plan of physician’s private office.

Figure 10-15 Floor plan of a physical therapy specialist.

Figure 10-16 Chemotherapy infusion suite at George Washington University Med...

Figure 10-17 A section of the lobby of the High Point Regional Medical Cente...

Figure 10-18 Floor plan for the shared entry between the University Medical ...

Figure 10-19 Floor plan of a private patient room in Alegent Lakeside Hospit...

Figure 10-20 A typical hospital private patient room.

Figure 10-21 QC chair used in hospital patient rooms for patient and visitor...

Figure 10-22 The medical/surgical visitors’ waiting area at Sentara Northern...

Figure 10-23 Nurses’ station on a medical/surgical unit. This renovation cre...

Figure 10-24 Floor plan of the Brookdale Urgent Care Center.

Figure 10-25 The reception area and lobby at Brookdale Urgent Care Center....

Figure 10-26 Floor plan of children’s dental office. The openness of the pla...

Figure 10-27 Waiting room in a children’s dental office. The open receptioni...

Figure 10-28 Contemporary dental operatory. Windows provide daylight and ret...

Figure 10-29 Four plans for dental operatories.

Chapter 11

Figure 11-1 Reception area and lobby of the Carlsbad by the Sea active-senio...

Figure 11-2 Floor plan of the assisted-living wing for the Homeplace at Midw...

Figure 11-3 Floor plan of an Alzheimer’s unit. Note how corridor allows move...

Figure 11-4 Floor plan of the main level of the K.C. Wanlass Adult Day Care ...

Figure 11-5 Living room area of the Carlsbad by the Sea Senior Living Facili...

Figure 11-6 Notice the screened-porch areas and centrally located kitchen in...

Figure 11-7 Corridor treatment at the Alta Vista assisted-living facility in...

Figure 11-8 Dining room design uses easy-to-move chairs on casters. The artw...

Figure 11-9 The flooring used in the fitness room at Generations is designed...

Figure 11-10 View of the family room in the Shaker-style assisted-living fac...

Figure 11-11 A variation in the design planning of a dining room in an assis...

Figure 11-12 Example of a large one-bedroom unit within an assisted-living f...

Figure 11-13 Resident room in a skilled care center.

Figure 11-14 An example of a shared bedroom space in a long-term care unit....

Figure 11-15 A model plan for the bedroom space in a memory-care apartment. ...

Figure 11-16 A special-feature Memory Wall at Generations at Agritopia.

Figure 11-17 This social space in a memory-care community provides a homey a...

Figure 11-18 Resident bedroom in a skilled nursing property at the Homeplace...

Figure 11-19 Patient bedroom that is simple in design yet provides a pleasan...

Figure 11-20 Living room at Hospice of the Valley, Phoenix, AZ.

Chapter 12

Figure 12-1 Reebok Fitness Center with machines and weights areas.

Figure 12-2 Notice the different functional elements in this day spa lobby....

Figure 12-3 Furniture floor plan for Massage Experts spa.

Figure 12-4 Spa treatment room at Massage Experts.

Figure 12-5 Floor plan of the golf clubhouse at the Ritz Carlton at Dove Mou...

Figure 12-6 Bar area in a golf clubhouse.

Figure 12-7 Golf club pro shop at the Ritz Carlton Desert Mountain, Tucson, ...

Figure 12-8 Clubhouse dining room with view to patio. Ritz Carlton Tucson....

Figure 12-9 Floor plan for locker room areas at Ritz Carlton Desert Mountain...

Figure 12-10 Locker room. Ritz Carlton Dove Mountain.

Figure 12-11 Presentation theater at the Mid-Continent Regional Center for H...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

DISCLAIMER

Preface

Acknowledgments

Begin Reading

Appendix

Glossary

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

v

vii

xvii

xviii

xix

xxi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

535

536

537

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

Designing Commercial Interiors

FOURTH EDITION

Christine M. Piotrowski

Copyright © 2025 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial intelligence technologies or similar technologies.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

The manufacturer’s authorized representative according to the EU General Product Safety Regulation is Wiley-VCH GmbH, Boschstr. 12, 69469 Weinheim, Germany, e-mail: [email protected].

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Applied for:

Hardback ISBN: 9781394201686

Cover Design: WileyCover Image: Photo by Mark Boisclair, Design by Fred Messner/Phoenix Design One

I first want to dedicate this to my family and friends for all their support.

I also want to dedicate this book to all the designers and students who have made this a better world by their efforts in the design of commercial interiors.

To my parents, Casmer and Martha, for watching over me while this was written.

DISCLAIMERThe information and statements herein are believed to be reliable, but are not to be construed as a warranty or representation for which the author or publishers assume legal responsibility. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. This book is sold with the understanding that the publisher and the author are not engaged in rendering professional services. Users should consult with a professional where appropriate. They should undertake sufficient verification and testing and obtain updated information as needed to determine the suitability for their particular purpose of any information or products referred to herein. No warrant of fitness for a particular purpose is made.

All photographs, documents, forms, and other items marked “Figure” or “Table” are owned by the organization, association, design firm, designer, photographer, or author. None of the figures or tables in this book may be reproduced without the express written permission of the appropriate copyright holder. A few manufacturers and products are mentioned in this book. Such mention is not intended to imply an endorsement by the author or the publisher of the mentioned manufacturer or product.

Preface

The commercial interior design profession has changed and, therefore, this edition has been influenced by those changes. The importance of global and cultural influences on design continues to impact all types of facilities. Sustainable design and wellness are critical issues in the design of commercial interiors, whether that means specifying low-VOC paints or helping a client achieve a high level of LEED or WELL certification. Accessibility for an aging population is an ongoing concern that is an absolute necessity in planning any of the facilities covered in this book. Security and code issues continue to be of utmost importance. The health impacts of the pandemic on the design and planning of facilities may have moderated, but remain an issue for designers, property owners, employers, and users of commercial spaces. These issues and their impacts are discussed throughout the chapters.

Interior design remains a problem-solving activity for all who are or wish to be involved in the design of commercial interiors. Practitioners and students are requested to plan and specify interiors that are aesthetically pleasing, yet these interiors must also be functional and help meet the business goals of the client. No designer can solve the client’s problems without appreciating the purpose and functions of the business. An ongoing focus of this book is the importance of learning the “business of the business.” Understanding the business interests of the specific commercial facility is essential to help the interior designer make informed design decisions. Doing research about a facility before beginning to design and plan a project may not be fun, but research is an indispensable part of successful interior design practice.

The fourth edition remains a practical reference for many of the design issues related to planning a variety of commercial interior facilities. Each chapter has been revised with input provided by reviewers and practitioners on issues important to the profession to meet today’s practice standards. It retains its focus on the types of commercial design spaces most commonly assigned as studio projects and those typically encountered by the professional interior designer who has limited experience with commercial interior design. The book is organized similarly to the third edition. The subject matter can be used by professors in whatever sequences are required for their specific classes. Professionals seeking information about specific types of facilities can easily reference the relevant chapters they need.

The first four chapters provide an overview of important issues that have an impact on commercial interior design work. Chapter 1 remains an introduction and overview of the commercial interior design profession. It gives the student a glimpse of what it is like to work in the field and where the jobs are. Chapter 2 includes material concerning the critical issues of global and cultural impacts, a discussion on sustainable design, LEED certification, updated codes information, and a brief overview of product specification principles. The discussion of the fundamental issues concerning the design of accessible restrooms remains in this chapter.

Chapter 3 focuses on research and the project process. Research is an important element of the design process; by carefully studying a project, the commercial designer can develop evidence to back up any design decisions—decisions that go beyond aesthetics. Discussions in this chapter include research methodologies, problem solving, evidence-based design, and concept development. Project goals and programming are also covered in this chapter.

Chapter 4 concerns project management and its importance to understanding the whole of the design process. Many important topics in project management are included here to help the student realize that a project cannot be completed without someone managing all the parts and pieces involved. Topics included in this overview are the role of the project manager, working relationships, project delivery methods, the integrated design process, dealing with client expectations, and an overview of the overall project process. A section on adaptive reuse—previously called adaptive use—is included in this chapter. Adaptive reuse is especially important as projects frequently are in spaces that already exist and often have had a different life.

The chapters that focus on the types of commercial facilities were selected based on the comments by reviewers and suggestions by designers. They are also the most common categories of commercial facilities that a professional may encounter. These are also the categories of facilities most often assigned in studio classes. They are corporate and small offices, lodging, food and beverage facilities, retail, healthcare, senior living, and a variety of recreational facilities.

New material appears in chapters to discuss topics of interest to the specific type of facility. In addition, each of these remaining chapters also discusses topics such as sustainable design, safety, codes, space allocation, furniture, and mechanical systems. Special attention in Chapters 5 and 6 has been paid to the changes in the general philosophy of office interiors. Chapter 5 focuses on overall design topics such as collaborative office spaces, wellness, the knowledge worker, and changes in planning. Chapter 6 focuses on design elements of office facilities including the design differences in open and closed plans. Information on the changing lodging guest is included in Chapter 7. Chapter 8 looks at changes in food and beverage facilities and Chapter 9 provides an overview of retail facilities. A discussion of the forces impacting healthcare and senior living design is included in Chapters 10 and 11. Chapter 12 provides an overview of various recreational facilities. Of course, brief discussions on the impact of the pandemic on all types of commercial facilities have also been added.

The detailed “Design Applications” sections in Chapters 6 through 12 have been updated with relevant new information and are provided to clarify important characteristics in designing these facilities. A few of the “Design Applications” discussions include: basic planning and the design of any size office as well as the design of the small professional office and the home office, the full service lodging facility, full service restaurants, quick-service restaurants, generic small stores, specialized medical practices, urgent care facilities, assisted-living facilities, hospice care facilities, and fitness centers.

Color images enrich the text with examples of the work of professional interior designers. Example floor plans and additional photos enhance discussions of design detail and design applications.

Lists of key terms that are fundamental to the chapter have been placed at the end of each chapter in this edition. These terms as well as other important terms that are italicized within the text highlight important chapter terminology. All these fundamental and important terms are included in the updated Glossary. The general references and websites relevant to the chapter are updated and remain at the end of each chapter. The Appendix includes revised website addresses of trade associations affiliated with the design industry along with website addresses of relevant periodicals. With these references, readers can obtain more detailed and specific information about the many different commercial interiors discussed. This combination will make this book an important reference for all readers.

I hope that this fourth edition will be a valuable resource as you undertake the interior design of commercial facilities. Whether you are a student or a professional, I hope that it will help you enjoy this very exciting and challenging career.

Christine M. Piotrowski

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deep appreciation to everyone who has supported this book over the years and provided encouragement in the preparation of this revision. Any textbook requires the input from numerous individuals. The comments of reviewers and others have been especially helpful in developing this revision. Thank you to designers and educators for their advice. It is also very important to sincerely thank educators who recognize this book as an important reference for their students.

I would particularly like to thank the designers and photographers who have made their work available through contributions of photos and drawings. The willingness of designers and photographers to provide images and drawings has made this book special as these images help the reader understand many aspects of commercial interior design. There are too many to name individually, but I want to give sincere thanks to all. Their names and/or their company names are provided in captions throughout the book.

Every effort has been made to correctly provide the proper credit information of interior designers, architects, photographers, and others along with the projects if the client chose to be identified. We apologize for any errors or omissions that may have occurred.

I want to thank the staff at John Wiley & Sons for their tremendous support, guidance, and assistance in the production of this book. I especially would like to thank Todd Green, Executive Editor, who encouraged the revision of this book, Kelley Gomez, Editorial Assistant, and S. Indirakumari, Managing Editor. Also a big thank you to all the other production support staff who helped bring this book to reality, especially Susan Dunsmore. And as always, a big thank you to Amanda Miller, Group VP and General Manager, who, as my first editor with John Wiley & Sons has supported my work over many years.

Finally, I also want to thank my family and friends for their patience and support as I prepared this fourth edition.

Christine M. Piotrowski

CHAPTER 1Commercial Interior Design

The opportunities in commercial interior design are endless. Commercial interiors are those of any facility that serves business purposes. This includes a variety of spaces beyond the obvious restaurants, hotels, and professional offices of many kinds. A textile showroom where you might pick up samples for a client, an athletic club where you work out, or a daycare center are other examples of commercial interiors. These are businesses that invite the public in for some reason or other. Others restrict public access but are business enterprises, such as corporate offices or manufacturing facilities. Commercial interiors are also part of publicly-owned facilities, such as libraries, courthouses, government offices, and airport terminals, to name a few. All these facilities and many others represent the kinds of interior spaces created by the division of the interior design profession commonly called commercial interior design.

These interiors can be as exciting as an elegant jewelry store on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, or a casino in an international hotel (Figure 1-1) or simply a small office for an accountant. A commercial interior can be purely functional, such as the offices of a major corporation or a small-town travel agency. It may need to comfort and treat the ill, as in a healthcare facility. It can also be a place to relax, as in a spa.

There are many ways to specialize or work in interior design and the built environment industry. Of course, the built environment industry includes those professions that are involved in the development, design, construction, and finishing of any type of building. Specializing can be very sensible, as the expertise one gains in a specialty can provide added value to clients. Be careful not to create a specialty that is too narrow, as there may not be sufficient business to support the firm. Numerous specialty suggestions are listed in Table 1-1 on p. 11

While the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the overall economic impact of interior design, it showed gains post pandemic. Interior Design magazine reports on the industry’s 100 largest design firms. In the April 2023 issue, it reported approximately $4.97 billion in design fees were generated by these firms in commercial projects alone in 2022 (Zimmerman 2023, 29). This indicated growth from previous years and substantial recovery post pandemic. It must be remembered that this figure and the information in the article reflect only a portion of the total commercial interior design industry because it only relates to the top 100 firms reported by the Interior Design giants.

Figure 1-1 High-limit area. Casino at the Venetian Resort, Macao.

Reproduced with permission of Wilson Associates.

There are ever-increasing challenges to commercial interior design and the business environment in general. The ups and downs of the economy influence any type of business. Technology has impacted how many consumers use many types of businesses. Government regulations can change and have changed how interiors can be planned and specified. And, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic profoundly challenged businesses’ and the commercial interior designers’ reaction to the work that they do for clients. Understanding the challenges affecting businesses is part of the work of the commercial interior designer. These types of topics will be discussed in other chapters in this text.

These terms are relevant to discussions in this chapter and throughout the book:

Business of the business: Gaining an understanding of the business goals and purpose of the client before or during the execution of the project.

Commercial interior design: The design of any facility that serves business purposes. May be privately owned or owned by a governmental agency.

Furniture, Fixtures, & Equipment (FF&E): All the movable products and other fixtures, finishes, and equipment specified for an interior. FF&E is also called furniture, furnishings, and equipment.

Stakeholders: Individuals who have a vested interest in the project, such as members of the design team, the client, the architect, and the vendors.

Spec: This is a slang term used to indicate a building that is developed and built before it has any specific tenants. Developers of commercial property are “speculating” that someone will lease the space before or after construction is completed.

This chapter begins with a brief historical overview of the profession. An essential part of this chapter is the discussion of why it is important for the commercial interior designer to understand the client’s business. It continues with an overview of what it is like to work in this area of the interior design profession. A brief discussion of topics focused on design professionalism concludes the chapter.

Historical Overview

It is always helpful to have some historical context for a topic as broad as commercial interior design. This chapter provides a brief overview to set that context. Other chapters also include a brief historical perspective on the specific facility type. An in-depth discussion of the history of commercial design is beyond the scope of this book.

One could argue that commercial interior design began with the first trade and food stalls centuries ago. Certainly, buildings that housed many commercial transactions or that would be considered commercial facilities today have existed since early human history. For example, business was conducted in the great rooms of the Egyptian pharaohs and the palaces of kings; administrative spaces existed within great cathedrals and in portions of residences of craftsmen and tradesmen.

Another example comes from lodging. The lodging industry dates back many centuries, beginning with simple inns and taverns. Historically, hospitals were first associated with religious groups. During the Crusades of the Middle Ages, the hospitia, which provided food, lodging, and medical care to the ill, were located adjacent to monasteries.

In earlier centuries, interior spaces created for the wealthy and powerful were designed by architects. Business places such as inns and shops for the lower classes were most likely “designed” by tradesmen and craftsmen or whoever owned them. Craftsmen and tradesmen influenced early interior design as they created the furniture and architectural treatments of the palaces and other great structures, as well as the dwellings and other facilities for the lower classes.

As commerce grew, buildings specific to business enterprises such as stores, restaurants, inns, and offices were gradually created or became more common. Consider the monasteries (which also served as places of education) of the twelfth century, as well as the mosques and temples of the Middle East and the Orient; the amphitheaters of ancient Greece and Rome; and the Globe Theatre in London built in the sixteenth century. New types of interiors slowly began to develop. For example, offices began to move from the home to separate locations in a business area in the seventeenth century, and hotels began taking on their grand size and opulence in the nineteenth century (Tate and Smith 1986, 227). Furniture items and business machines such as typewriters and telephones, as well as other specialized items, were also being designed in the nineteenth century.

The profession of interior decoration—later interior design—is said by many historians to have its roots in the late nineteenth century. When it began, interior decoration was more closely aligned to the work of various society decorators engaged in residential projects. Elsie de Wolfe (1865–1950) is commonly considered the first professional, independent interior decorator. Sparke and Ownes called de Wolfe “the mother of modern interior decoration” (2005, 9). De Wolfe supervised the work required for the interiors she was hired to design. She also was among the first designers, if not the first, to charge for her services (Campbell and Seebohm 1992, 17). In addition, she was one of the earliest women to be involved in commercial interior design. She designed spaces for the Colony Club in New York City in the early 1900s (Campbell and Seebohm 1992, 7).

Although most of the early commercial interior work was done by architects and their staff members, decorators and designers focusing on commercial interiors emerged in the early twentieth century. One woman designer most commonly associated with the beginning of commercial interior design was Dorothy Draper (1889–1969) (Tate and Smith 1986, 322). She started a firm in New York City and, beginning in the 1920s, was responsible for the design of hotels, apartment houses, restaurants, and offices. Her namesake firm still exists.

There were many changes in the building industry in the late nineteenth and into the twentieth century. These changes were led by the designs of architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Charles Eames, to name just a few of these early change influencers, each having a profound impact on interior design of commercial facilities.

Commercial interiors changed for many reasons in the second half of the twentieth century. Technological changes in construction and mechanical systems, code requirements for safety, and electronic business equipment of every kind have impacted the way business is conducted throughout the world. Consumers of business and institutional services expect better environments as part of the experience of visiting stores, hotels, restaurants, doctors’ offices—everywhere they go to shop or conduct business. Interior design and architecture must keep up with these changes and demands. This is one of the key reasons that an interior designer must be educated in a wide range of subjects and understand the business operations of clients.

The interior design profession also grew in stature in the twentieth century with the development of professional associations, professional education, and competency testing. The decorators’ clubs that existed in major cities in the 1920s and 1930s were the precursors of the current two largest interior design professional associations in the United States, the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID) and the International Interior Design Association (IIDA). The Interior Designers of Canada (IDC), founded in 1972, is the professional association and advocacy group for designers in Canada. Provincial associations also exist in Canada. As interior design is a global profession, many associations are located in other countries to serve their professionals. An Internet search for “international design associations” will help you identify numerous such organizations.

Through the efforts of ASID, IIDA, and IDC a governing body was formed to administer, validate continuing education programs, and serve as a central registration body of continuing education courses. The Interior Design Continuing Education Council (IDCEC) is that organization.

In respect to professional education, competency testing, and licensing of design professionals, the most significant advances occurred in the second half of the twentieth century. Here are a few of those milestones:

In 1963, the Interior Design Educators Council (IDEC) was organized to advance education in interior design.

In 1970, the Foundation for Interior Design Education Research (FIDER) was incorporated to serve as the primary academic accrediting agency for interior design education.

In 1974, the National Council for Interior Design Qualification (NCIDQ) was incorporated to provide for competency testing.

In 1982, Alabama became the first state to pass title registration legislation for interior design practice.

In the 1990s, the Interior Design Continuing Education Council (IDCEC) was formed. The purpose of this organization is to approve and support continuing education.

In 1993, the Center for Health Design was organized for those interested and involved in designing healthcare facilities.

In 2005, FIDER changed the name of the organization to the Council for Interior Design Accreditation (CIDA).

In 2005, the Center for Health Design developed the Evidence-Based Design Accreditation and Certification (EDAC) certification.

In 2013, the National Council for Interior Design Qualification changed the organization name to Council for Interior Design Qualification (CIDQ). The examination retains the NCIDQ acronym.

Approximately in 2016, the Fitwel certification program was launched.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic began and profoundly impacted businesses—including the interior design profession—throughout the world.

2021 and after, a greater emphasis and development of e-design and virtual design techniques by interior designers.

Even when coupled with the brief history sections in other chapters, this overview does not give you a complete history of commercial interior design nor the profession. It continues to evolve with changes in technology, product design, regulations, and numerous other forces on businesses in general and the profession. However, if you would like more information, many titles are listed in the references for you to explore.

Understanding the Client’s Business

Designing any kind of commercial interior without asking questions and understanding the business of the business could lead to project failure. Consider this; would you want your doctor to diagnose an illness or pain without first asking you questions about how you feel? Of course not!

Understanding “the business of the business” refers to understanding the goals and purposes of a business. In fact, it is important to understand the business specialty even before seeking projects in that specialty. To try to acquire a project for a medical office suite, for example, without knowing something about how doctors’ offices function is a recipe for disaster. This knowledge should result in design solutions and outcomes that are functional, not solely focused on the aesthetic, and lead to more creative design concepts.

The needs of each type of client will vary by their business focus. For example, space planning and product specifications are different for a pediatrician’s suite than for the offices of a cardiologist. Planning decisions are different for a small gift shop in a strip shopping center than for one in a resort hotel. Understanding this from the outset is critical for the design firm.

Businesses seek interior design firms that are not “learning on the job” with the client’s project. Creative solutions that are aesthetically pleasing are important to many clients. However, a creative and attractive office that does not work or is not safe is not helpful to the client. Creativity alone does not mean success in commercial interior design.

Five important issues influence the design direction and eventual solutions to commercial projects. They are:

Type of facility. Each type of facility has many different requirements. Space planning, furniture specification, materials that can be used, codes that must be adhered to, and the functions and goals of the business are just some of the many factors that influence the interior design, based on the type of facility.

Location. The location of the business will relate to the client base the business wants to attract. The dollars spent on the interior may very well be different based on the project’s location. Customer expectations will be greater when the business is located in a high-end area versus a strip mall.

Target customer. When a business begins its planning, it determines a target client base. Different design decisions will be made based on that target client. For example, a hotel located along an interstate will have a different target client than those of a resort in the mountains.

The actual product of the business. Design specifications for a coffee shop will be quite different from those for a luxury full-service restaurant. The design of the office of an advertising agency will vary from that of a law firm.

The client. The client can be a sole proprietor (of any kind of commercial facility), a branch of a multilocation business, a developer, or the board of directors of a nonprofit. The client might be the board of directors and the facility manager for a major corporation, or the local jurisdictional governing body for the school district.

Every client has different business goals, and the interior designer is challenged to satisfy all their unique demands. Thus, understanding the business of the business and its characteristics is important to understanding how to go about designing the interior. The more you know about the hospitality industry, for example, the more effective your solutions will be for a lodging or food service facility. Gaining experience and knowledge about retailing will be an advantage for you in designing any kind of retail space. In fact, the more you know about any of the specialty areas of commercial interior design, the greater your success will be in working with those clients.

Working in Commercial Interior Design

The design of commercial interiors is complex and challenging. The number of project details can be enormous, and organizing those details is of paramount concern for the designer. Commercial interior design requires the designer to be attentive to details, be comfortable with working effectively as part of a team, and have the ability to work with numerous stakeholders. He or she must also understand the client’s type of business before accepting a contract.

Often the interior designer works with employees of the business rather than the owner. However, design decisions must also please the owner. Few commercial design projects will be undertaken without the involvement of an architect. Being able to collaborate with the architect as the team seeks to meet the functional and aesthetic goals of the client is critical.

Teamwork and collaboration are necessary components in commercial design. Because projects can be very large, it is difficult for one or two people to handle all the work (Figure 1-2). Willingness to be part of the team, effectively doing one’s job, and offering to be involved are not only important in completing the project but also bode well for advancement in the firm. Whether your role is small (which will be the case at the beginning of your career) or you are the prime designer/project manager, as your experience grows, your ability to work with a team and collaborate with others is fundamental to success. So do not be surprised if project managers and senior design staff are in charge of projects rather than an entry-level designer.

Figure 1-2 Employee lunch areas are often places for teamwork and collaborative discussions.

Courtesy of Gary Wheeler, FASID. WheelerKänik, London, England.

Effective communication goes hand in hand with teamwork. Project communications occur by email, texting, telephone, written documents, and electronic means such as smartphones and laptops. These electronic devices provide many aids for designing and achieving ideas and decisions. PowerPoint presentations, Pinterest, or other computer-based media will be utilized for marketing and progress presentations. Mandatory in commercial interior design is skill with computer-aided drafting (CAD) and other graphic media.

Today’s interior designer must be tech savvy in relationship to software for the production of design documents and business management. Knowledge of CAD software is no longer a wish but a necessity. Utilization of 3D modeling software is part of commercial interior design production and marketing. Familiarization with ZOOM for video conferencing became commonplace during the pandemic and continues to be utilized in place of traveling to meet with clients. Even Virtual Reality (VR) tools help designers envision interiors and allow clients to see the possibilities. Other tools will no doubt be available as technology continues to upgrade and become part of the profession.

Verbal and written communication must be conducted in a professional manner. Whether you are standing in front of your client discussing the project, sending an email, or texting a vendor (not while you are driving!), be professional in what you say and how you say it. Older clients may not easily interpret the shorthand used by many younger designers. One more caution: Those electronic messages don’t just disappear; they are almost always archived by the client. What you say in an email must be what you can do or you could have legal and ethical problems.

A commercial design project involves satisfying individuals and groups in addition to the actual property owner or business owner. First, to be clear, there are many types of property and business owners, including:

A single business owner developing a building and needing tenant improvements

A business owner wishing to renovate or adapt a building to a new purpose

A developer having an office or retail structure built on spec

A corporation building a branch facility

A chain remodeling a property

A government entity building agency offices, schools, or the like

Of course, the property owner or business owner is the key decider. Yet there are others within and even outside the basic business whom the designer must consider in developing design concepts. Here are two key influencers beyond primary property owner that must be considered for a commercial project: employees and customers or clients.

Employees will also have an impact on and perhaps have direct input into the design of the facility. Research shows that if the facility has been designed with a pleasing and safe atmosphere as well as a functional environment, employees will work more effectively. An exciting interior for a restaurant that attracts large crowds willing to spend on food and drink will bring better-quality waitstaff to serve those customers. Unfortunately, employees don’t usually get to vote on design decisions; however, they may vote unofficially through their willingness to stay with the company and serve its clients effectively.

A third influencer is the customer who comes to the facility. In some instances, the ambience of a restaurant or the beauty of the setting influences whether a customer returns. In other circumstances, ambience plays a minimal role in this decision. The relationship of a doctor to a patient is more important than the doctor’s exquisitely designed office. If your local city government offices had marble on the walls and floors and gold faucets in the restrooms, as a citizen you might think that your tax dollars had been misspent. Designing for these various users is challenging, to say the least.

As for working on a project itself, commercial interior design projects follow all phases of the design process. Of course, the interior designer’s responsibility within each phase will vary based on the project, licensing issues, and the designer’s experience. Missing steps or doing any of the tasks halfheartedly can be disastrous. Margins for error are often nonexistent, as many projects are fast-tracked, where design plans for one phase of the project are created as construction is proceeding on another phase to ensure early occupancy. Figure 1-3 is an example of the kind of design drawings often required.

Commercial interior designers must know how to manage a project as well as design it. This task is defined as project management. Project management is a systematic process used to coordinate and control a design project from inception to completion. Project management requires leadership, planning, coordination, and control of a diverse set of activities, people, money, and time in order to accomplish the goals of the design project. Project management is primarily the responsibility of experienced designers who oversee the team of designers and others who are involved in a project.

Project delivery methods have evolved into four approaches. These will be discussed in some detail in Chapter 4. However, brief definitions are provided here to lend context to the overall scope of this chapter.

Design-bid-build. This is the traditional project delivery method, where a client hires a firm to design the project. It is then sent out for competitive bids to multiple suppliers, and a contract is awarded to the firm chosen by the client.

Construction management