Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

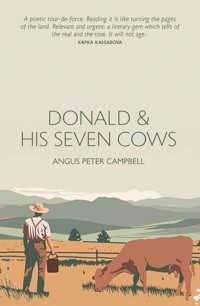

- Sprache: Englisch

Perhaps Donald Michael MacDonald invented the round mile, all 2,240 yards of it. Donald and his seven cows, walking the same steps each day through the past and the future, the fairy knoll and the poison pool, the eternal truths and the unknowable possibilities. Rarely does Donald venture beyond the round mile, for he has no need to: all of history can be found on his land. Yet the wind farms, the spaceport, and the American billionaire with his Big House all threaten the peace Donald has cultivated and guarded as fiercely as he protects his animals. He loses a part of himself – and most of his herd – before an unexpected old friend helps Donald and his seven cows to reclaim their path, even as their island is transformed by a new age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 265

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ANGUS PETER CAMPBELL is from South Uist. He went to Garrynamonie Primary School and Oban High School, where his English teacher was Iain Crichton Smith. After graduating in Politics and History from the University of Edinburgh he has worked as a kitchen porter, tree planter, builders’ labourer, lobster fisherman, journalist and writer.

A beyond-wonderful book.—DR JOHN DEMPSTER, Inverness Courier

A wonderful novel.—NICHOLAS COLLOFF, Director, Argidius Foundation, Geneva

An absolutely brilliant read, but also a very illuminating insight into the Gaelic psyche.—ROB MACNEACAIL

One of the most beautifully written books I’ve ever read, (and one of the two books I’ve ever read that I will re-read).—MICHELLE, on Goodreads

You can almost hear the waves crashing on sand, the cries of seabirds and cows grazing on seaweed in this entrancing yet urgent tale of a lost past and a worrying future. South Uist author Campbell gives us a day in the life of Donald who, with his cows, walks the same ‘round mile’ on the land of his forebears. But his peace is threatened by ‘progress’ – wind farms and a spaceport. Poetic and important, it is a modern classic.—SUNDAY POST

Almost every novelist of modern times has been touched by the literary genre of magical realism. Other than Louis de Bernieres, it is difficult to think of a British writer who has explored the form more fully, and with such increasing authority, than Angus Peter Campbell… A clever, beautiful and important book.—ROGER HUTCHINSON, West Highland Free Press

A marvel: an astounding piece of writing.—DR IAIN MACKINNON, Cultural Scholar, Isle of Skye

By the same author:

The Greatest Gift, Fountain Publishing, 1992

Cairteal gu Meadhan-Latha, Acair Publishing, 1992

One Road, Fountain Publishing, 1994

Gealach an Abachaidh, Acair Publishing, 1998

Motair-baidhsagal agus Sgàthan, Acair Publishing, 2000

Lagan A’ Bhàigh, Acair Publishing, 2002

An Siopsaidh agus an t-Aingeal, Acair Publishing, 2002

An Oidhche Mus Do Sheòl Sinn, Clàr Publishing, 2003

Là a’ Dèanamh Sgèil Do Là, Clàr Publishing, 2004

Invisible Islands, Otago Publishing, 2006

An Taigh-Samhraidh, Clàr Publishing, 2007

Meas air Chrannaibh/ Fruit on Branches, Acair Publishing, 2007

Tilleadh Dhachaigh, Clàr Publishing, 2009

Suas gu Deas, Islands Book Trust, 2009

Archie and the North Wind, Luath Press, 2010

Aibisidh, Polygon, 2011

An t-Eilean: Taking a Line for a Walk, Islands Book Trust, 2012

Fuaran Ceann an t-Saoghail, Clàr Publishing, 2012

The Girl on the Ferryboat, Luath Press, 2013

An Nighean air an Aiseag, Luath Press, 2013

Memory and Straw, Luath Press, 2017

Stèisean, Luath Press, 2018

Constabal Murdo, Luath Press, 2018

Tuathanas nan Creutairean, Luath Press, 2021

Constabal Murdo 2: Murdo ann am Marseille, Luath Press, 2022

Electricity, Luath Press, 2023

Eighth Moon Bridge, Luath Press, 2024

First published 2025

Reprinted 2025

ISBN: 978-1-80425-262-8

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 12 point Sabon by Main Point Books, Edinburgh

© Angus Peter Campbell 2025

Contents

Introduction by Angus Martin

Donald & his Seven Cows

Acknowledgements

Introduction

WHEN ANGUS PETER CAMPBELL asked me if I would read and comment on a book he had written, I was slightly apprehensive because it was a work of fiction and I hadn’t read a novel or short story since last century.

I agreed, because for many years Angus Peter, whom I have never met, has publicly endorsed my work in both poetry and history, and I’d be a liar if I claimed to be immune to appreciation, since the subjects I choose to write about have never attracted a wide readership. He, as a writer, is perhaps in a similar position, because much of his work has been published in his native Gaelic.

We were both born in 1952, two months apart. His earliest years were spent in South Uist and mine in Kintyre: geographically far apart but once connected by a common language and heritage. A cultural gap between these two communities opened in the nineteenth century. The last Gaelic speakers in my family were John Martin and Sarah Campbell, great-grandparents. When I attended secondary school in Campbeltown in the 1960s, some of the pupils from North Kintyre had native Gaelic-speaking grandparents, but before the end of the century these Gaelic speakers had all died and taken the language with them.

That irreversible force of attrition has now visited the remotest parts of the Gàidhealtachd which had seemed safest. The Uist Angus Peter Campbell grew up in – with Gaelic-speaking crofters on the machair lands, planting and weeding and harvesting and tending their stock – now seems to him like a ‘dream’, and I think that Donald & His Seven Cows is essentially about travelling through the landscapes of that dream and back to a beginning which is also – as cycles dictate – an end.

Many of us whose childhoods were happy – or happy enough, I should say – increasingly return in memory, as we age, to the formative places and people of the past. There is now, however, a great difference in the character and degree of that nostalgia, because social and cultural and environmental changes have accelerated at such a rate in the past fifty years that one can almost stand in a long-familiar place, look around and ask, ‘Where am I? What has happened?’

Some of us know, and fear, what has happened. There has been a terrible disconnect from the natural world and fewer and fewer people work the land and the sea.

When I grew up in Campbeltown, the fishing industry was thriving and there was a fishing community within the wider community: families which had intermarried for generations, with sons following their father to sea. Most of these boys, unless they were exceptionally academic, didn’t consider any other future. But overfishing ruined the herring and white fish industries, and the continuity was broken. The relatively few boats which now work from Kintyre ports are catching shellfish species which, aside from lobster, were dumped over the side as unmarketable a hundred years ago. Instead of a healthy fishing industry, we have miserable fish caged offshore in pollutant ‘farms’.

It is the same with agriculture: the community has dwindled; most farmers work the land alone or with a few family members; and old arable fields are rank with rushes or choked with bracken. Alien conifers cover the uplands, with giant wind towers sprouting among them, and the latest gimmick is ‘carbon offsetting’: the ploughing of good farmland to plant woodland, which, when the time comes that farmers are again needed to do what they always did best, will stand, tree by uneatable tree, as testimony to political ineptitude and capitalist greed.

That’s a little of what I know about Kintyre. About the Uist of Angus Peter Campbell’s childhood, I know nothing from personal experience, but this book has stories to tell, not only of an inevitably lost childhood but also of a lost community, with its ancient language and culture sacrificed on the altar of ‘progress’. The ‘ceilidh house’ has been replaced with a big television screen on a wall and computers and mobile phones have ushered in a multitude of phantom communities and unmet ‘friends’ to replace the real community which exists minutes away from the locked door and its blinding ‘security light’.

This book is essentially about a day in the life of Donald, who accompanies his seven dairy cows around the croft. In reality, it is unlikely he would have dedicated entire days to the herding of cattle; yet the buachaille (herd) of history did just that. He, or she, was usually a child sent out with the cows to keep them from straying on to neighbouring grazings or into fields of growing crops (this at a time when fencing was rudimentary or non-existent).

The reader is witness to a ritualistic round of visitations – transmuted from the Stations of the Cross in Catholic worship – as Donald moves, in his leisurely way, into and out of the past, remembering the dead and meditating on change. Places, naturally, are intrinsic to the journey – as to any journey – but his travels are confined within a small space, and the sights he sees are so familiar to him that he claims to know ‘every blade of grass’. An impossibility, to be sure, but one with its roots in truth, for those of the past who worked the land had intimate knowledge of its every feature, and had names for these features: fields, rocks, knolls, ridges, ravines, hollows, springs … everything. And the names had stories behind them, some forgotten, some obscure, and some remembered.

As I know, from having collected the lore of my native Kintyre from the last tradition-bearers, since the mechanisation of farming and the exodus from the land, most of these minor place-names have died with the families which preserved them. I quote from my book Kintyre Places and Place-Names, its source that gloomy memoir, Night Falls on Ardnamurchan:

The poet Alasdair Maclean gave eloquent expression to that loss [of place-names]. As a boy in the township of Sanna, Ardnamurchan, he roamed all over the neighbourhood, sometimes accompanied by his grandfather, who had a name for ‘every least hillock, every creek and gully’. Maclean felt that such knowledge set his grandfather apart, invested him with a ‘form of spiritual privilege’, so that he ‘lived in a different landscape from me, seeing it in a different way and – I came to feel – being seen differently by it’.

I admitted at the start that I hadn’t read fiction since last century but didn’t give a reason. Here is my attempt at an explanation (not that it should matter to anyone else, except in the frame of this undertaking): perhaps because I’ve spent most of my life researching and writing social history and reconstructing real lives (as far as ‘reality’ can be perceived or trusted), I tired of artificial stories and stopped reading them.

Angus Peter Campbell’s story is certainly a species of fiction, but the elements of history and folklore and cultural memory kept me interested to the end, and, increasingly, the strange atmosphere of the story put me under its spell.

I suspect that it is not a narrative that will entertain a reader in search of conventional plot development and gratuitous excitement. Rather, it is the diffident, rambling testimony of a man – an amadan (fool) in the eyes of his neighbours – who is voluntarily trapped in the past and unwilling to engage with the present or surrender to the future.

Donald & His Seven Cows has perhaps not been written for a mass readership – the title itself is defiant in its mundanity – yet I wish Donald and his little herd well in their journey to the outer world. They carry messages from the past to inform readers in the future that there were (and are) other ways of living and thinking, tried and tested by millennia of down-to-earth experience and supernatural engagement.

Angus Martin

Campbeltown, Kintyre, June 2025

1

I KNOW THIS mile so well. It’s a round mile. Like the full moon. Two thousand two hundred and forty yards, by the Gaelic way of counting, beginning from the end of the byre where I walk the cows from every morning round our world. We stop twelve times. Every two hundred and twenty-four steps. These are places where we spend our days.

I know they say a mile is one thousand seven hundred and sixty yards. But not here. They told me that official measure when I went to school but I didn’t believe the teacher, because I’d paced it out every day before school with my grandfather and it was two thousand two hundred and forty yards of his steps and four thousand four hundred and eighty yards of mine. I had to take two steps for every one of his, but now that I’ve walked like him for the past fifty years I can assure you it’s two thousand two hundred and forty yards. Even if I have to stretch a bit now to make them. A ceum (step) here is two-and-a-half feet.

Maybe I invented the mile. I don’t know, for no one else knows it exists. They just see me wandering about as if the cows are leading me, haphazardly, to where grass and more grass is. But no, it’s not like that. We lead each other, for we all now know the route, and where the puddles are, and the stones to avoid, and that little stream which freezes over in the winter and the hollow green shade where we all rest in the summer. We go where we all agree to go. The ground is good and solid under my feet. It makes me feel secure. If it didn’t, I would just rise and fly off into the air and Maisie and the herd might look at me ascending for a moment and then resume their grazing. Or they might fly off with me and join the great Fingalian cows of the sky that scholars call the Milky Way. The cows are greater than me in so many ways. Stronger. Patient. More productive.

Looking up and looking down are two different things. I tend to look down to see the marks the cows’ hooves make in the earth and the way the bell heather is already beginning to bloom though it’s hardly beyond the Feast of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, and I have to remind myself to look up to see the flecks of cloud now in a dragon shape on top of the hill and the way the sky is already bright blue far to the north-west. It’s a puzzle solved every day. You only see what’s there when you’re not really looking for it.

It’s not that we walk a trail every day, or a marked path. There’s liberty. The cows can wander where they want, but over the years they’ve come to know where they should go, the rocky bits to avoid and where the pastures green lie. By now I’m into the fiftieth generation, so they’re born with that knowledge. They move slowly because they have all the time in the world. It takes the full day to travel a mile. We walk sunwise. East, north, south, west. Eternity will be a quiet joyous day like this, herding. Breathing slowly.

It hasn’t been easy. For them or me. For me especially, because I’ve had to mould and shape the mile without leaving any signs, any clues that it’s a carefully worked out path. For next thing other people might start using it, and then Morrison the Council Officer will be round with his Jeep putting signs up telling everyone about it. Do Not Enter. Danger This Way. All these signals folk need to have to know what’s safe and what’s not. A few months ago he asked me to start cleaning up the cows’ dung on the round mile because all that dirt would spoil the official walk they’re planning to build. It’s the future. A walking path without any beasts spoiling their shoes. Once I go, there will be no more cattle. Half the mile with shit bags to keep things tidy. Poop bags, they call them on the notices with those little red boxes for collecting them.

‘This place belongs to the herd,’ I told him. ‘Without them, the earth will die.’

Sometimes I think they’re the ones making the earth as they go along, leaving their hoof marks in the grass and mud, chewing up everything that is in front of them and fertilizing it at every second step as they plod forwards. On rare windless days they swing their tails as they graze, to get rid of the flies.

I’ve had to be careful not to go mad. One year I twisted my knee and went to see Nurse MacLeish and after she examined me, she asked me if I was anxious. I didn’t really know what that meant, so I asked her.

‘Do you worry about things?’ she said.

‘Not much,’ I said.

‘What kind of things?’ she asked.

‘My cows,’ I said. ‘That they won’t grow properly.’

She left it at that, but it made me anxious, if that’s what it was. For she went on and talked to me about a disease called OCD which meant that people (and I knew fine she meant me) repeated things over and over again because they then feel safe, but the danger is that if the pattern is broken then their whole world falls apart. The knife to the right of the plate, the fork to the left, and the spoon above, or everything is chaos.

That’s me all right, but as far as I can make out everyone is like that. Every morning down the road I hear Janet Smith singing and talking to her hens. And every morning in the same order.

‘Dearg, tha thu an sin!’ (‘Red, you’re there!’)

‘Buidhe – ciamar a tha?’ (‘Yellow – how are you?’)

‘Gorm, a ghaoil!’ (‘Blue, my darling!’)

‘Ugh an-diugh, Uaine?’ (‘An egg today, Green?’)

‘’ille Dhuibh, robh thu modhail an-raoir?’ (‘Black lad, did you behave last night?’)

Every day like a liturgy, and each one cackles back to her in time. Miss Smith is very pious and goes to all the services, even when they’re not on Holy Days of Obligation. Whenever she visits anyone she always knocks three times on their door in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, to bless the house and the people in it. I rarely visit anyone, but for a while I also took to knocking three times at the byre door in the morning to bless Maisie and the herd, my beloved treasures. I didn’t want to be like Janet though, so I began doing it seven times, adding the names of saints Peter and Paul and Mary and Joseph. Thing is, the herd then took to lying-in and not stirring until they were blessed the seven times, when they’d rise in unison. So I stopped it, knowing they’d be blessed anyway, innocent creatures as they are.

During weekdays Miss Smith walks with one hand over her shoulder as if she’s always carrying a sack of potatoes. Her parents and grandparents were potato-merchants, forever transporting tatties on pack-horses from the fields out to the steamship for sale on the mainland. Every day is like a mystery story. How is it that Janet always manages to say the same things, in exactly the same tone of voice, while the hens all cackle back in different ways? I think it depends on the weather. They sound mournful when their feathers are all soaking wet.

And the schoolteacher. I see him driving past every morning, his right hand nonchalantly holding the wheel and his left a cigarette. When the weather is fine, he has the car window open, and I can hear music. It’s always the same too: operatic singing, I think they call it. He’s also an artist. Converted his old father’s byre into a studio and works there after school and sells his paintings on Saturdays. They’re all about the sea, painted in a bright blue colour I’ve never seen in any water. There are no people or cows or sheep or dogs in his pictures. I suppose everyone wants a life free of bother. We know so little about anyone. They hide whole worlds.

Mind you, it’s good we’re not all the same. Just like Maisie and the herd. They all have their different ways. Not one face or foot or moo is like another’s, though people just call them all ‘cows.’ Maisie slow and gentle, and the younger ones gobbling up the grass impatiently as if it might suddenly run out at the next chew.

We all have our dreams and ways, don’t we? I would like to have a ranch with a thousand head of cattle and hundreds of wild horses. Our hopes prepare us for the day ahead. Otherwise we wouldn’t know what to do when we meet our hens or cows or neighbours. It would be like the first time we saw them and we wouldn’t know what to say or do. When we do meet we talk about the weather, which gives us the choice of talking about everything or nothing. Sometimes I think the day has happened already before I wake up.

I always hear the herd when lying in bed in the morning. I sleep well enough, from dark to dawn, summer and winter. Like a bear. It’s all the same to me, though I hear folk complaining how different the two seasons are. Of course they are. I know that. It’s all light during the summer and the grass grows and the cows feed on it so well. The mile journey takes longer then, because they spend so much time enjoying the clover, munching away to their hearts’ content. I don’t hurry them. Why would I? We have all day long to circumnavigate the world. Whether a long sunny summer’s day or s short stormy winter’s one makes no difference. We spend it together.

I like that. Summer. Sometimes I stand around resting my chin on my hand on my stick on the ground watching them eating up all that goodness. Buttercups and daisies and orchids and thistles. My mouth waters. They enjoy it so much. It’s good to see them happy. I keep one good inbye field as green as I can until late autumn to fatten them up before market time. They look at it yearningly all year long, and when I open the gate around the Feast of the Assumption, they run in like little children unsure for a while where to start eating. Pudding Field, I call it, because it reminds me of myself as a child when Mum made the best pudding in the world, rhubarb crumble with custard, on Friday nights when I came home from school. After dinner she used to sit in the warm corner by the stove, eyes screwed up, pins in her mouth, sewing. She was forever patching up Grandfather’s clothes, as well as her own tweed skirts and, once, she knitted me up a teddy bear from the remnants of Grandfather’s old tweed jacket which had gone beyond repair. His head was a mix of blue and green, his body grey, one leg white and one leg black. I stuffed him with sheep’s wool and she stitched him all together. I named him Patch.

I suppose you have to name a thing before you know what it is. A dog. A stone. A hill. A river. Otherwise you wouldn’t know what it was. It would just be a thing. A lump. Strange, though, that the thing remains itself no matter what you call it. Because I call a dog a cù in Gaelic. And a stone is a clach and a hill a beinn and a river an abhainn, though they still remain what they were no matter the language. I wonder if I’d be the same if I was called Angus or Murdo or Calum. I don’t suppose so, because then I would have heard things differently when I was in the cot and wouldn’t know myself if I was called by someone else’s name. We used to sing and pray in Latin before they changed it all to Gaelic though I can still say it all as it was from the beginning when the priest made the sign of the cross saying In nomine Patris et Filii et Spirit Sancti Amen Introibe et altare we’d all say Ad deum qui laetificat juventutem meam. It was the same then as it is now though the words sounded all different. Older.

In the winter, the mile journey is so different. I leave them to find the scraps of grass and drops of unfrozen water as I follow along. Maisie looks up at me now and again, as if to say, ‘Donald, can we just go back home? Please? And it’s not because I’m a coward. It’s because I’m wise.’

But I don’t let them. Not because I’m cruel, but because I love them. I suppose I love them more than anything else in the world. For what else is there to love? And what a word that is anyway. I never hear anyone use it, except the priest on Sunday when he speaks about it. It’s easy then.

The herd need to learn that winter can be enjoyed as much as summer. That after we do our mile-long circuit in snow and wind and rain, the reward is lying in their warm byre while I sit by the fire with my tea. We’ve endured. We’ve done it and survived once more! And enjoyed it too! O, I know that takes a while to achieve, because at first it’s really depressing, first thing in the morning, watching the wind and rain sweeping in horizontally from the north and knowing fine that sleet and hailstones will follow, and that it will be all dark and getting darker as the day goes on, but once I’ve put my long johns and semmit and long woollen socks and my everlasting moleskin trousers on I’m ready for anything. We don’t wish the rain or the winter away. We just prepare for it, as we do for sun and summer. Fresh straw in the byre. Those holes in the wall filled in. Gates and loose things tied down. Extra peats in by the fire. But I tell you, none of these practical measures take as much strength as believing in our daily walk.

And they sense it. I can hear them sniffing and snorting out in the byre as if they too are putting on layers for the task ahead, though all they have is the thick hair God gave them, and the patience and endurance handed down to them in their mother’s milk. And Angus the bull: what a fine specimen he’s been, going at it with patience and diligence over these past ten years, as was another Angus before him and Angus and Angus and Angus back through the generations. We all look forward to his arrival every year. He comes from the Department of Agriculture farm in Aberdeenshire and he moves from village to village for a whole month.

So, we all stand there in the faint morning light. The herd lined up behind Maisie who always leads and is standing mournfully in the byre door as the rain pounds the sodden yard in front of her. In the summer the light is so bright it blinds us. In the winter it’s so dark we see everything, since we look so carefully. I once had an outbreak of rats in the barn but I made an aoir (a satire) telling them to go north and they did, because a curse, like a blessing, has infinite power. They never came back.

I no longer use a stick. In the early days, after my grandfather died and I was on my own with the cows, I did. To guide and goad and push them along, but I always felt it was wrong. And they knew it: looking at me sadly whenever I hit them on the rump or prodded the stirk in front.

‘Good God. What a brute. A savage. Doesn’t he know we know?’ they all cried.

So gradually I gave the beatings up and replaced them with nods and hand-slaps and curses and words of rebuke and encouragement. They liked that. You have to let folk know how you feel, one way or the other. They like when my hand comes hard down on their back urging them on. The touch. Or the ‘Hoi’ I shout when one steps out of line, or the look I give when one barges the other. The one who had barged always looks at me then, like a sorry child. So I forgive.

‘The herd will forgive you as you forgive them,’ Grandfather said.

But especially they like it when I sing. I never used to because I always believed that was a woman’s business. My mother was a wonderful singer. She had an endless number of songs, and though her voice wasn’t that tuneful, or strong, the contents of the songs made up for everything. I only ever understood half of them when I was younger and still don’t understand them all, though I’ve remembered them and sing them myself now when I’m out on the moor and the mood strikes me.

For it has to strike you. Not like a bolt of lightning, which will kill you, but like a soft breath of wind from the west, which keeps the midges and clegs and flies away on a good summer’s day. You can hardly feel it at first, though I know the signs: the way the rushes in the river begin to bend ever so slightly, and that distant sort of hum in the air as if an oven or a door had been opened and a bit of warmth let out. Then you can feel the wind itself, as it floats across the machair and the cattle turn their heads that way, glad to be alive in the breeze.

The song thing is like that. It can happen any time. Say if I’m down on the machair digging the rigs where I’ll plant the potatoes next spring, and I hit a stone or some obstacle in the ground and it makes me think of how Bonnie Prince Charlie also met with so much opposition on his way to London. Even Clanranald himself, my chief, telling him to go home that wonderful day he arrived in Eriskay, having sailed all the way from France. What a thing to say to the heroic prince, who was setting the plough fair for his people. What a harvest they could have had.

Or poor Seasaidh Bhaile Raghnaill and her family’s opposition to her love for Dòmhnall, and how they eloped through a window and sailed for Australia. Sometimes I sing her song when milking the cows and I swear in the name of God that the milk flows sweeter and creamier when I do, because the cows are so happy that Seasaidh and Dòmhnall lived happily ever after. The only purpose of a song is to do something practical like make him fall in love with her or increase the creaminess of a cow’s milk. Otherwise there’s no point in singing it.

The thing is that the cows now look after themselves. They always have, in a way, because cattle and sheep can naturally sense where good grass lies and where fresh water is and where danger lurks, but I suppose through the generations they’ve also learned that. Genetically, I mean, because all that knowledge passes down from cow to calf, from mother to daughter, so that as each calf is born, he or she already knows the way, the mile. It’s like a song. If a mother sings her daughter a song and she sings it to hers and so on, it only takes thirty of them to sing it before you’re back a thousand years ago. I suppose they bring their own histories.

I sell the young bulls and heifers to MacTavish who comes round every year at Martinmas. The stock is kept clean from the Aberdeenshire Anguses.

I’ve had to learn it though. This mile I circumnavigate every day. I know every blade of grass and where every pebble and little stone lies and where the stream runs weak and strong and where the poisonous plants are. Nothing is hidden on it. I could walk it blindfold and know by the smell of the air and the contour of the ground where exactly I am. It’s the one thing that’s certain in our lives. And yet so much changes every day. See – that mark the hailstones made on the grass overnight, and the way the standing stone is damp this morning. The only way to see a thing is by looking at it so well you can see what you don’t expect to see.