Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: 16Lives

- Sprache: Englisch

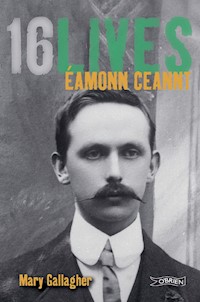

The son of a Head Constable in the Royal Irish Constabulary, by the age of twenty-five, Éamonn Ceannt was married with a young son. He played the uilleann pipes and was passionate about the Irish language. His commitment to a politically independent, Gaelic-speaking Ireland led him from the classrooms of the Gaelic League to the National Council of Sinn Féin and the senior ranks of the Irish Volunteers. He was a member of the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which planned and carried out the Rising of Easter 1916, outright rebellion against the world's biggest imperial power. During Easter week 1916, he was Commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Irish Volunteers and a signatory to the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. His severely depleted battalion held the strategic South Dublin Union until ordered to surrender. He was executed by firing squad on 8 May 1916. 'an epic new series of books' - RTE Guide on 16Lives

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 483

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The 16LIVESSeries

JAMES CONNOLLY Lorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLIN Brian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETT Honor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALY Helen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTON John Gibney

ROGER CASEMENT Angus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADA Brian Feeney

THOMAS CLARKE Helen Litton

ÉAMONN CEANNT Mary Gallagher

THOMAS MACDONAGH Shane Kenna

WILLIE PEARSE Roisín Ní Ghairbhí

CON COLBERT John O’Callaghan

JOHN MACBRIDE Donal Fallon

MICHAEL O’HANRAHAN Conor Kostick

THOMAS KENT Meda Ryan

PATRICK PEARSE Ruán O’Donnell

Dedication

For my family and friends

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Honor O Brolchain for introducing me to Michael O’Brien, who trusted me to write this biography of my grand-uncle, Éamonn Ceannt. I am equally grateful to my editor, Ide Ní Laoghaire, who rescued my initial draft from the byways of historical context and family anecdotes. Lorcan Collins and Ruán O’Donnell, the series editors, together with Emma Byrne, Nicola Reddy and the team at O’Brien Press, were always helpful and supportive.

My thanks are also due to the archivists and staff at the National Library of Ireland, National Archives of Ireland, the Bureau of Military History, the Archives Department of University College, Dublin, the Allen Library, the Royal Dublin Society, Dublin City Library and Archive, and South Dublin County Libraries. They were unfailingly helpful and courteous. I am particularly grateful to the librarians in my local library, Ballyroan Library, who acquired many of the books and references I needed. On-line access to original sources made my life immeasurably easier. The ability to search for the unusual name of Ceannt gave me access to a wide range of sources I might otherwise have missed. They include the Census of Ireland 1901 and 1911, the witness statements from the Bureau of Military History, the Irish Court of Petty Sessions Court Registers at findmypast.ie and a wide range of national and local newspapers at Irish Newspaper Archives Online.

When William Henry wrote the first biography of Éamonn, Supreme Sacrifice: The Story of Éamonn Ceannt: 1881–1916, (2005), he approached my late sister, Joan, and myself for assistance. We were delighted to help but came to recognise the limitations of our knowledge. In the past few years I have had the opportunity to rectify that and I hope William will forgive any shortcomings in the information with which we then provided him.

Before attempting to write Éamonn’s life story, I had the great pleasure of returning to my alma mater, University College Dublin. My thanks are due to the School of History and Archives, in particular Professor Michael Laffan, Dr Lindsey Earner-Byrne, Professor Diarmaid Ferriter and their colleagues. I am also grateful to my fellow students, particularly Margaret Ayres, Tom Burke, Declan O’Keefe and Conor Mulvagh. My thanks are similarly due to Sean Murphy and my fellow students in the certificate course in Genealogy and Family History for a thorough grounding in genealogical research methods.

Éamonn naturally wrote many of his letters, diaries and articles in his beloved Irish, and I am particularly grateful to Siobhán Ní Mhathúna and my cousin, Tuhye Gillan, for their help in translating them.

My thanks are also due to Dr Joe McPartlin, Trinity Centre, St James’s Hospital, who organised a seminar, ‘Easter 1916 at the South Dublin Union’, in April 2014. Dr Patrick Geoghegan, Trinity College, chaired and the speakers were myself, Prof Davis Coakley and Paul O’Brien. Prof Coakley very kindly showed me around the site of the SDU at St James’s Hospital.

Finally, I want to place on record my deep gratitude to my family – living and departed. My late grandfather, Michael Kent, wrote our family story in his diaries from 1911–1920. His daughter, Joan Kent, preserved them, tenderly wrapped in brown paper and hidden away on top of a wardrobe. She also kept Bill Kent’s letters to Michael, from the Boer War to Flanders, and many other family photographs and memorabilia. My sister, Nora Sleator, her husband Louis, and my nieces Niamh and Clodagh have supported me patiently throughout the long months of research and writing, as have the extended Ceannt, Gillan and Sheehy families. My equally patient and supportive friends regularly ask, ‘how’s Éamonn getting on?’ I hope this book will answer their question!

16LIVES Timeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers are founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Constance Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelor’s Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eoin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand in Kerry. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork harbour.

1916, 22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt Rock.

10pm. Eoin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) meets to discuss the situation, since MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Irish Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVES Map

16LIVES - Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell, 16 Lives Series Editors

Contents

Chapter One

• • • • • •

1881–1899

A Constabulary Childhood

When Éamonn Ceannt (Edward Thomas Kent) was born in Ballymoe, County Galway, on 21 September 1881 to Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Constable James Kent and his wife, Johanna, few could have imagined that he would live to become Commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Irish Volunteers, that he would sign the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and that he would be executed by firing squad following a hastily convened field court martial on 8 May 1916.

The year 1881 started badly in the west of Ireland with an exceptionally hard winter. Although the deprivation was not comparable with the period of the Great Famine, well within living memory, hunger was widespread and starvation was an ever-present threat. But for James and Johanna Kent the situation was less bleak than for many of their neighbours. James had a good pensionable job with regular pay and subsidised accommodation.1

James Kent had been born on 14 July 1839 in Rehill, near Mitchelstown, County Cork.2 He joined the RIC on 15 January 1862.3 His family farmed in Lyrefune, a townland of Ballyporeen, County Tipperary.4 When he joined the RIC he gave his occupation as ‘labourer’ and was recommended as a young man of good character and a suitable member of the RIC by his parish priest. Like most of his contemporaries, he had received an elementary education in reading, writing and arithmetic.5 A tall, well-built man, he was in excellent health and easily met the physically demanding conditions for the force. For a landless younger son like James, the RIC presented a welcome opportunity for improvement.6

His wife, Johanna, was from Buttevant, County Cork, and they met when he was posted in nearby Kanturk. By the time Éamonn was born in 1881, they had been married for nearly eleven years.7 Although money would have been tight in the early years of their marriage, James was now approaching the maximum salary of £70 per annum for a constable with nearly twenty years’ service.8

Like many of her contemporaries, Johanna spent the early years of her married life caring for their young children. At the start of 1881 they had five children under the age of eleven: William Leeman (Bill), John Patrick (JP), Ellen (Nell), James Charles (Jem) and Michael (Mick). Their fifth son, Edward Thomas (Ned) – who was subsequently to adopt the Gaelic translation of his name, Éamonn Ceannt – was born in September that year and their youngest son, Richard (Dick), two years later. Even if she had the time or inclination, the regulations of the force prevented Johanna from taking up any occupation for profit outside the home, such as dressmaking, nor could she take in lodgers.9

As for James, he was part of a quasi-military force of men whose daily lives were highly regulated. They were always ‘on duty’ and were expected to be available at all hours. They could not serve in their own home localities or those of their spouses. When they were assigned to a new location, their priority was to get to know their new community. As a young recruit, James would have received training in the elements of police duties, including proficiency in ‘the use of arms and military movements’, and would have operated under a Code of Regulations that required him to know his neighbours, including their political views.10 Like most of his contemporaries, James’s duties entailed collecting information, patrolling the countryside, and acting as an officer of the courts, reporting such things as prosecutions for allowing two donkeys to wander on the public highway,11 or for having a dog without a licence,12 or for being drunk on the public street.13 Until the late 1870s the Irish countryside had been quiet, from a policing point of view, and the life of a policeman a ‘rather mundane and tedious occupation’.14 Such evictions as took place were the responsibility of the sheriff and his bailiffs, with little police involvement.15 In the early 1880s the environment within which James Kent and his RIC colleagues worked changed irrevocably. The Land League, set up by Michael Davitt in Mayo in 1879, was soon established as a national movement under Charles Stewart Parnell and, although the League was committed to peaceful means, agrarian strife was on the increase, putting considerable strain on the RIC.16 The effectiveness of the new tactics of the ‘boycott’, in which landlords or their agents were shunned by whole communities, did not stop some of the extreme agitators from resorting to the old agrarian tactics: haystacks were burned and the lives of landlords and their agents were sometimes at risk. In 1880, at the height of the land war, over two thousand families were driven from their homes and ‘outrages’ totalled 2,590.17

In this tense climate, the role of the RIC became increasingly politicised and their duties multiplied to include keeping evicted farms under observation to prevent trespass, attending and recording public meetings, protecting individuals thought to be at risk and arresting and escorting prisoners. All of these extra duties, while making the members of the force unpopular with their neighbours, also led to significant extra work, ‘without the least compensation or consideration’.18

During these difficult times in the west of Ireland, the mighty British Empire was at the height of its power. The evolving technologies of steam and telegraph made it possible to control an ever greater proportion of the global land mass and to dominate world trade. Yet in one small corner of the Empire the seeds of its future decline were being sown. The ultimate success of the Irish National Land League would lay the foundations for a movement that, with Éamonn as one of its leading members, would shake the Empire to the core.

A month after Éamonn’s second birthday, his father was promoted to Head Constable and, in December 1883, was transferred from Ballymoe to County Louth, where the family was initially based in Drogheda. Just 56km from Dublin and 120km from Belfast, Drogheda was a thriving port with a strong industrial base. This move, from the heart of impoverished rural Galway to the relatively prosperous east coast, must have been both exciting and stressful for them, and indeed, Éamonn’s brother Michael remembered that shortly after they arrived in Drogheda, the toddler, Éamonn, ‘wandered and was lost for part of a day and night!’ Éamonn started in the Christian Brothers’ School at Sunday’s Gate, Drogheda, around the age of five. He got homesick the first day and was sent home with Michael. Their mother was astonished when she saw them playing happily in the garden.19 Éamonn was a sensitive child – ‘a little oddity’, according to Michael – and he had quite a temper. His mother was known to call him a ‘little weasel’ when he was in bad form. The family later moved out to the country district of Ardee20 and Éamonn attended the De La Salle Brothers’ School there.

Éamonn loved the countryside and, with his brothers, enjoyed ‘rolling hoops, fishing, rambling over the bog, and hailing with joy the occasional circus and the crowds that came to the Mullacurry Races’.21 Still, life for Éamonn and his family would have been quite regulated as Constabulary wives and children were expected to behave in accordance with Constabulary regulations.22

After three decades in the RIC, James Kent retired from the force in 1892, aged fifty-three.23 He was entitled to take voluntary retirement after his thirty years’ service, with a pension based on his full salary. Like many of his contemporaries, however, this was not the end of his working life. Also, the influence of the RIC on its retired members did not conclude upon their departure from the force. With no absolute ‘right’ to a pension, they could find their income cancelled for improper behaviour over the remaining years of their lives: ‘in the case of retirees, it was a matter of – once a policeman, always a policeman’.24

James was ambitious to see his children educated and able to better themselves in life, and in 1892 the family moved to Dublin. The eldest, Bill, stayed in Drogheda with the Christian Brothers25 and JP had already followed in his father’s footsteps and joined the RIC at the age of eighteen.26 James still had a young family, however. Richard, the youngest, was only nine years of age, and Éamonn was just about to start secondary (Intermediate) school.

The years during which the Kent family had lived in County Louth coincided with the strengthening of the Home Rule movement as Charles Stewart Parnell turned his attentions from land reform, where the battle was almost won, to building a disciplined party structure for the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) in Westminster in pursuit of Home Rule.

The move to Dublin brought the Kent family to the most wealthy and influential part of Ireland. Dublin was the capital city and Dublin Castle represented British rule in Ireland. The city was an important administrative and commercial centre with a population of about 350,000. Politically, however, it was a ‘Deposed capital, a city bereft of its parliament, a backwater in Irish politics’.27 Nonetheless, the city was changing. While the wealthy areas of Rathmines and Pembroke on the south side still housed the Protestant ascendancy and the wealthy professional classes, and the city’s teeming tenements had the dubious distinction of being among the worst in Europe, Dublin also had a growing Catholic middle class that was beginning to make its mark on the city’s commercial and cultural life.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the number of people who moved to Dublin from rural Ireland was insignificant compared to the numbers who left Ireland altogether, and most long-term migrants to Dublin, like the Kent family, had a reasonable degree of financial security.28 The move to Dublin presented James Kent with the opportunity to supplement his pension within a more prosperous environment while, at the same time, giving his growing family access to improved educational and career prospects. Living in an imperial port city also enabled the young Kents to glimpse the wider world outside Ireland. In an echo of the day on which James Joyce’s young Dubliner and his pal Mahony skipped school to watch graceful three-masted schooners on the Liffey discharge their cargo and to examine ‘the foreign sailors to see had any of them green eyes’,29 Éamonn and his friend Jack O’Reilly ‘used to go down to the quays when a foreign boat came in, to converse with the sailors’.30

The family’s first home was 26 Bayview Avenue, Fairview, a brick-fronted one-storey-over-basement house between Ballybough Road and North Strand Road. It was just twenty minutes’ walk from the centre of Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street).31 Also a short walk away from the family’s new home was the Christian Brothers’ O’Connell School, North Richmond Street, where Éamonn and the younger brothers of the family resumed their education. The school had been established in 1829 by Edmund Rice, the founder of the Christian Brothers, and named after Daniel O’Connell, who laid the foundation stone.

‘North Richmond Street, being blind, was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian Brothers’ School set the boys free’,32 so wrote one of Éamonn’s contemporaries in the school, the young James Joyce, who attended O’Connell’s School for a few months in 1893 before moving on to the Jesuit Belvedere College. Another contemporary in the school was Sean T O’Kelly (Ó Ceallaigh), later President of Ireland.33 Éamonn and Sean’s paths would cross many times in later years. Other near contemporaries, whose fates would closely echo that of Éamonn, were Sean Heuston and Con Colbert. Colbert would fight in Éamonn’s 4th Battalion Irish Volunteers during Easter Week 1916 and the two men, together with Sean Heuston, would all die by firing squad on the same day, 8 May 1916.

Theirs was the first generation of poorer Catholic boys to have the opportunity to receive a secondary, or, as it was called at the time, Intermediate, education. Throughout the last two decades of the nineteenth century, there had been growing pressure to provide a competitive examinations system in Ireland that would open up access, for Catholics in particular, to jobs in the civil service and to professional careers. The Intermediate Education (Ireland) Act had been passed by Parliament in 1878. The Act established an examining board with an annual sum of £32,500, which was distributed by way of money prizes for pupils and results fees for schools.34

Valuable ‘Exhibitions’, worth up to £50, were awarded to students with the highest marks. From the start, Éamonn’s school results were excellent. In the Preparatory Grade Examinations of 1894, ‘Edward T Kent’ was awarded an Exhibition of £20, tenable for one year – one of fourteen such awards to the O’Connell School that year. Since they were paid directly to the family, the Exhibitions made a significant contribution to the family finances. He also received a Composition Prize of £2 in French.35 Although the curriculum included the Celtic language, Éamonn didn’t study the subject – there may have been a pragmatic reason for his decision, as the weighting for marks allocated to subjects varied, with the classics (Latin and Greek), together with English and mathematics, each being worth 1,200 marks; German and French, 700; while Celtic (i.e. Irish) was worth only 600.36 The following year he was less successful, being awarded a Third Class Book Prize (£1).37 During that year, however, tragedy had struck the Kent family when Johanna, Éamonn’s mother, died on 6 February from acute phlebitis (blood clots in the leg) at the age of fifty-four.38 Éamonn was only thirteen at the time, while Dick, the youngest in the family, was eleven and was just joining Éamonn at the O’Connell School. Éamonn, always a shy, reserved boy, received the news of his mother’s death with ‘silence and immobility’.39

In spite of his loss, Éamonn kept his attention on his studies in the year ahead, and in 1896 he was again awarded an Exhibition – Junior Grade – of £20, tenable for three years. Getting a good education remained a priority for the Kent family. In his notebook for that year, Éamonn wrote that:

a good school education is the all important thing for a young person about to embark on his fortunes in the world and is absolutely essential to succeed. Fathers who are careful for the interests of their children are often sorely perplexed in looking about for their future state in life. Even when no state has been definitely decided upon they take as their motto – education first – employment after … We must read if we wish to acquaint ourselves with the doings of the world – we must write if we wish to express our opinions or communicate with friends … The more we know, the more we wish to know: we are never tired getting additional knowledge – after our school days are over.40

These were far-sighted words from a young boy who, in later life, was renowned for never going anywhere without a book in his pocket and for haunting the National Library of Ireland for material on his researches into Irish music, language and culture.

At the age of fifteen, Éamonn was already thinking about his future career. His friend Peter Murray was advising him on the ‘true road to civil service success’,41 while his own notebook records his thoughts on ‘Why I should not like to be a soldier’. It’s likely that the idea of a career in the army was a topic of conversation for the Kent family as Éamonn’s eldest brother, Bill, joined the Royal Dublin Fusiliers shortly afterwards. Éamonn, on the other hand, was already clear that taking the queen’s shilling would not figure in his plans. With no Irish army in prospect in 1896, he wrote, with some maturity, if not foresight, that he did not want to be a soldier:

because the paths to glory lead but to the grave;

because I consider the pen is far mightier than the sword;

because I am Irish and no Irishman should serve in a foreign army;

because as much honour and eminence may be gained in a civil profession;

because I have no desire to be a target for foreign adversaries;

especially because I am Irish and no Irishman can serve his country while in a foreign service.42

In spite of his academic achievements, Éamonn was a normal teenager. In his school diary he recorded the events of his sixteenth year. Éamonn started the school year that September by getting up every morning at 6.15am to get organised for the day though moaning about having to go to school on a ‘regular wintry morning, dark, gloomy and cold’.43

With a bright future ahead of him, it was only occasionally that he gave a thought to Irish history. The Christian Brothers were exceptional during the nineteenth century for teaching Irish history as a subject in its own right. They did so from their own textbooks, which highlighted the themes of ‘Irish resistance to English invasion; of Irish suffering resulting from English persecution; of Irish struggle against English oppression’. Moreover, they stressed the splendour of the old Gaelic civilisation which the arrival of the English had gradually suppressed and displaced.44 Éamonn’s teacher, Mr Maunsell, tended to ‘wax enthusiastically about love of country’, but it was not sufficient to generate much enthusiasm from the young Éamonn. On 6 October 1896, he mentioned in his notebook only that it was the ‘anniversary of a man named Parnell’s demise’. Éamonn was far more interested in the fact that he ‘made [his] first debut as an orator today before an audience of two in the drawing school’. He was practising for a speech that his teacher Mr Duggan had asked him to deliver at the school prize-giving banquet the following day. To his own surprise, not to mention that of his family, he made an excellent speech. He called it ‘a very pleasant evening. I perpetrated a – a speech …’

In the new year, 1897, Éamonn was back into the school routine – though, as for many adolescents, early rising had become more of a problem. In January, he admitted that ‘I have got into the fashion of late rising and nothing can induce me to rise before it is absolutely necessary.’ All in all, life in January that year was a bit bleak. The school was gloomy, with snow lying on the roof and thick on the ground. The journey home was beset with snowball fights and, while he ‘eluded the gang in Richmond Cottages’, he was obliged to ‘run the gauntlet for the Sackville Avenue crowd’ – and run he did. He remarked in his diary that ‘he that fights and runs away, will live to fight another day!’

Things only got worse in February. ‘Me miserum! Alas and alak! Misfortune never came singly,’ he moaned as the boys were prohibited from playing football, causing Éamonn to wish, ‘may it always thunder, rain, hail or snow when the originator of this barbarous scheme walks out!’ On top of that, he was finding lessons ‘simply dreadful’ and ‘the leather [for corporal punishment] on the point of being used’, which would have been unusual in his case.45

There were some bright spots that term, however. In March the comic Chums notified Éamonn that he had been awarded a prize of an illustrated volume in their pocket-money competition.46 His brother Michael also won a prize. The prizes were a copy of Fame and Glory in the Soudan War and a ‘chivalrous narrative entitled Under Bayard’s Banner’. Both arrived in the post on St Patrick’s Day, and both would influence Éamonn in later life, although not in the way their authors had intended.

The following month, April, Éamonn tried out his name in Irish in his school diary – ‘Eamun Tomas Ceannt’. By this stage in the school year, exams were looming. The summer term meant cramming for the exams and Éamonn hoped that ‘eleven hours a day, three days a week, and nine and a half hours the other three’ should leave him in ‘a pretty fair condition to spout our knowledge in seven weeks’ time’.

In spite of his fears before the exams, Éamonn’s academic success continued and he was again awarded a Middle Grade Exhibition of £30 for two years. The school year came to an end and the summer holidays began. The following day the Kent family left Bayview Avenue and moved to their new home at 27 Fairview Avenue, Clontarf.

In 1898 Éamonn was awarded a Retained Senior Grade Exhibition of £30, allowing him to progress through to final exams.47 Not many of his contemporaries were as fortunate. Most boys in the Intermediate education system benefited only from its early stages, and just 4.4% of the total number of students examined in Éamonn’s final year progressed to senior level.

Like many of his later associates in the Irish–Ireland movement and in the republican movement, Éamonn left school and set out on life as a typical example of a Christian Brothers’ boy. He was well tutored, academically bright and ambitious. The question was, how would he put this to use?

Ireland was no meritocracy at the start of the twentieth century, and in spite of their education and the opening of access to jobs in the public sector and local government, many young Catholic men from poorer and lower middle-class backgrounds found their expectations frustrated.

Notes

1 Elizabeth Malcolm, The Irish Policeman (Dublin, 2006), p129.

2 National Library of Ireland (hereinafter NLI), Papers of Éamonn and Áine Ceannt, and of Kathleen and Lily O’Brennan (hereinafter Ceannt Papers), MS 41,479/8, Transcript of Shorthand Notes taken down by Michael Kent.

3 National Archives of Ireland (hereinafter NAI), RIC General Register of Service, James Kent, Number 27,415.

4 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 41,479/8, Transcript of Shorthand Notes taken down by Michael Kent; NLI Ceannt Papers MS 41,479/8, Irish Press, May 1932, Letter from James G Skinner, Clonmel, Co Tipperary; NAI Census of Ireland 1901 and 1911.

5 James Kent was fortunate to be part of the first generation of Irish children to benefit from the establishment of the national school system in 1831, see John Coolahan, Irish Education: Its History and Structure (Dublin, 2005), p58.

6 Thomas Fennell, The Royal Irish Constabulary ed. Rosemary Fennell (Dublin, 2003), p9.

7 Marriage Certificate of James Kent and Johanna Gallway.

8 Fennell, The Royal Irish Constabulary p9. For purposes of comparison, had James remained a farm labourer, he would have earned between 9s to 12s per week (c. £26 per annum), H D Gribbon, Economic and Social History, 1850-1921 in W E Vaughan Ed. A New History of Ireland VI, Ireland under the Union 1870-1921, (Oxford, 2012), p319.

9 Fennell, The Royal Irish Constabulary, p40. This ban was lifted following the 1882 Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Royal Irish Constabulary (1883) – see Elizabeth Malcolm, The Irish Policeman, (Dublin, 2006), p135.

10 Fennell, The Royal Irish Constabulary, pp8, 14 and 15.

11 Petty Sessions Order Books CSPS 1/4988, 24 October 1872 and CSPS 1/2325, 22 September 1877, www.findmypast.ie accessed 15 October 2012.

12 As above.

13 As above.

14 Malcolm, The Irish Policeman, p95.

15 Fennell, The Royal Irish Constabulary, p89.

16 Malcolm, The Irish Policeman, p94.

17 F S L Lyons, Ireland since the Famine (Glasgow, 1973), p165.

18 Fennell, The Royal Irish Constabulary, p98.

19 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 41,479/8, What I remember about Éamonn by Michael Kent.

20 Áine Ceannt, BMH WS 264.

21 Kent-Gallagher Family Papers, Draft Article by Lily O’Brennan – possibly the basis for an article in the Limerick Leader, Saturday 14 July 1934.

22 Elizabeth Malcolm, The Irish Policeman, p170.

23 NAI RIC General Register of Service, James Kent, Number 27,415.

24 Elizabeth Malcolm, The Irish Policeman, p212.

25 Kent-Sheehy Family Papers, Kent Family, Short Biographical Details by Rónán Ceannt, 25 January 1973. This family tree, compiled by Rónán, is known to be inaccurate in some respects so cannot be entirely relied upon. It is the only surviving record, however, of Bill Kent’s life before he joined the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

26 NAI RIC General Register of Service, John Patrick Kent, Number 54068.

27 Mary Daly, Dublin: The Deposed Capital, A Social and Economic History 1860–1914 (Cork, 1984), p1.

28 Daly, Dublin: The Deposed Capital, p16.

29An Encounter, in James Joyce, Dubliners, Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1993, London, p10.

30 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 41,479/8, Transcript of Shorthand Notes taken down by Michael Kent.

31 Thom’s Directory of Ireland, 1895–1914; Death Certificate of Johanna Kent, 16 February 1895.

32Araby, in James Joyce, Dubliners, Wordsworth Editions Ltd (London, 1993), p18.

33 Sean Ó Ceallaigh, BMH WS 1765.

34 Coolahan, Irish Education, p61. These prizes were initially intended only for boys but were, following pressure from a delegation led by Belfast womens’ rights campaigner Isabella Tod, extended to include girls.

35 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 13,069/44.

36 UCC Multitext project in Irish History, http://multitext.ucc.ie, accessed 24 July 2014.

37 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 13,069/44–45.

38 Death Certificate of Johanna Kent, 16 February 1895.

39 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 41,479/8, What I remember about Éamonn by Michael Kent.

40 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 13,069/44 – this appears to come from notes for an essay or a debate on the merits of education.

41 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 13,069/44, draft letter to a friend.

42 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 13,069/44.

43 Allen Library, Ceannt Collection. E Ceannt Handwritten School Diary.

44 Barry M. Coldrey, Faith and Fatherland; The Christian Brothers and the Development of Irish Nationalism, 1838–1921 (Dublin, 1988), p113.

45 Allen Library, Ceannt Collection. E Ceannt Handwritten School Diary.

46Chums was a British boys’ weekly newspaper that had gained in popularity after serialising Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson in 1894.

47 NLI Ceannt Papers MS 13,069/44–45.

Chapter Two

• • • • • •

1900–1905

A Busy and Enquiring Mind

As the new century opened, the prospect of Home Rule for Ireland seemed far away. The British Empire was fighting the Boer War in South Africa, and Eamonn’s brother Bill was out there, fighting on the British side. Young Éamonn, however, showed his emerging independence of spirit when he persuaded their sister, Nell, to make a Boer flag for him, which he hoisted on a tree at the end of the garden. It remained there until his father saw it and ordered it to be removed.1 Showing his true colours already, Éamonn would, as an adult, oppose recruitment into the British Army with every fibre of his being.

The young Kents were setting out on their various career paths. JP was serving with the RIC in Wicklow; Nell, who had trained as a dressmaker,2 was keeping house for her father and younger brothers in Fairview Avenue; Jem was working with his father as an assistant house agent; while Michael and Éamonn were considering their career options and Richard was still at school. Their father was supplementing his RIC pension by working as a house agent with an address at 138 Dorset Street. All members of the family living in Dublin were recorded in the 1901 census as speaking both Irish and English.3 His father’s knowledge of the Irish language had come as a surprise to Éamonn when he himself started to learn it.4

After leaving school, Éamonn considered a number of careers including that of newspaper reporter. He went so far as to do an interview with the editor of the Independent but ‘upon learning that he would be on duty by day and by night with little freedom, he changed his mind’.5 He refused to join the civil service ‘on the plea that it was British’, but later ‘consented to enter for the Corporation, remarking that the funds for the Corporation came from the Citizens of Dublin’. In the meantime, Éamonn tutored boys at Skerry’s Academy, which prepared students for civil service and university exams. 6

The enactment of legislation for the reform of local government in 1898 had transformed Dublin Corporation.7 The electorate was increased from around 8,000 to almost 38,000 and the Act removed the requirement for councillors to be property owners.8 Although the administration of local government was taken out of the control of large property owners and the local gentry, the franchise still excluded the majority of Dublin citizens who were lodgers paying less than four shillings a week in rent, and the many thousands who eked out an existence in the crowded tenements. Nevertheless, the change had an impact and, by 1900, the Corporation was dominated by the nationalist politicians of the United Irish League.9

During 1900, Dublin Corporation had decided that ‘all appointments to clerkships and kindred offices under this Corporation shall be made by competitive examination’.10 Éamonn started work in Dublin Corporation that same year and his was one of the earliest appointments under the new system. He became a clerk in the City Treasurer and Estates and Finance Office. His salary was £70 per year with an annual increment of £5, which he received regularly.11 His brother Michael followed him into the Corporation in February 1901. Both brothers soon signed up as members of the Dublin Municipal Officers’ Association (DMOA), which was set up in June 1901 for ‘the purpose of recreation and mutual advancement’ of Corporation employees.12 Éamonn was later elected Chairman of the Association and remained an active member throughout his career in the Corporation.

For Éamonn, his work in Dublin Corporation would be a means to an end. He did his work efficiently and effectively; his Constabulary upbringing and Christian Brothers education, together with his diligent personality, saw to that. Indeed, his wife Áine later recalled that ‘in the seventeen years that he worked in the Corporation, only once was he late, and that was a day on which he started from home on a bicycle and the storm blew him off it’.13

But the career opportunities available to an educated, lower middle-class Catholic in 1900 were never likely to provide enough challenge or reward for someone like Éamonn. A colleague recalled that ‘a brain such as his, always crowded with ideas, novel and interesting, seemed to chafe at the humdrum of routine and sameness’.14 He had to find his challenges elsewhere. For him, as for many of his contemporaries, that meant the nascent Irish–Ireland movement and, in particular, the Gaelic League. Before long Éamonn had developed an abiding passion for Irish language and music.

His interest was sparked by a chance visit, on St Patrick’s Day, to Gill’s booksellers in Sackville Street where he came across a book called Simple Lessons in Irish by Fr Eugene O’Growney of St Patrick’s College, Maynooth.15 This led to his joining the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge). The League had been established in 1893 by a small group of language enthusiasts that included O’Growney, Douglas Hyde, the son of a Roscommon clergyman, and Eoin MacNeill from County Antrim, then a young civil servant. The objective of the League was to revive the Irish language, which had been in decline throughout the previous century. It also aimed to foster an interest in Irish music and dance. From the beginning the League was both non-sectarian and non-political. After a slow start the influence of the League accelerated until, by 1904, there were nearly six hundred branches. Its most remarkable achievement at that time has been described as establishing ‘in the imaginations of some of the most ardent spirits of the new century, a sense of shared endeavour in the restoration of life to something precious that had come close to extinction’.16

This was certainly true as far as Éamonn was concerned. It also introduced the young man to a new circle of friends and acquaintances who would fundamentally shape his future direction in life. Among them was Frances (Áine) O’Brennan, the woman who, initially his student in the Gaelic League, was to become his wife and soulmate.

Éamonn attended his first meeting of the Central Dublin Branch of the Gaelic League on 18 September 1899 in the Rotunda. This was one of the most active branches in the League. Among the existing members were Eoin MacNeill and a young Patrick Pearse – two years Éamonn’s senior, Pearse was already a member of the Central Branch and had been co-opted onto the Coiste Gnótha (Executive Council) in 1898.17 This was heady company for Éamonn, a ‘tall, pale, serious-looking youth’ who was described by a contemporary Gaelic Leaguer as quiet, reticent and anxious to avoid the limelight.18

But from the start he was determined to master the Irish language. He initially inclined towards the Munster pronunciation but, as a contemporary recalled, ‘having paid a visit to Connaught, he adopted the standard of that province for his pronunciation and ever afterwards, Connaught had for him a strange fascination’.19 At the Feis Laighean agus Midhe for 1901, ‘There were three entries of Irish essays on “The National Festival” confined to students of not more than three years’ standing. Mr Edward T Kent carried off the First Prize.’20

He was also becoming known for his organisational skills and willingness to take responsibility for the routine work of the League. Within a year, Éamonn had been elected a member of a small sub-committee of the Central Dublin Branch, which was responsible for arranging monthly scoraíochtaí (music and dramatic events). These events had been started the previous January and ‘brought music and life from the libraries and theorists and placed it before the public … They have fought the music halls by showing that relaxation and sociability and enjoyment are possible in Dublin in a healthy natural atmosphere.’21

A contemporary on the sub-committee, Máire, recalled later that ‘when the question of programmes, posters etc. arose, the quiet voice said, “I’ll attend to that, Máire” and that work was well done. I need have no anxiety whatever about it … [Éamonn] made everything run smoothly, but never got, nor expected, the slightest thanks from anyone.’22

Throughout this time many of those who attended the branch meetings saw only the reserved side of Éamonn’s personality, a side of which he was well aware. But those who worked closely with him also saw his innate sense of fun. A contemporary later remembered two young men – Éamonn and Patrick Pearse – rushing to tell her an anecdote about the naming of Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street). Shy Éamonn was ‘stepping long legged over the forms towards me, and Pearse hurrying around the table’. Both young men were ‘choking with laughter’.23

On 18 November 1900, the Fairview/Clontarf Branch of the Gaelic League was established, with Éamonn as its first Secretary.24 When classes started, over ‘100 pupils attended and received tuition from Mr T O Russell, Mr E T Kent and Miss M Kennedy, B.A. … The subscription [was] one shilling per person, no charge being made for the children.’25 He was later, in 1903, elected President of the branch.26

In January 1902, Éamonn was co-opted onto the Leinster Feis Committee and was appointed, as its Secretary, to the Sub-Committee for Music and Dancing.27 In the years between 1903 and 1905 he was a regular representative of the Central Dublin Branch at the League’s annual Árd Fheiseanna. The Árd Fheis was the event at which delegates debated and decided the policy of the League and at which the Coiste Gnótha was elected. During these years Éamonn was one of the branch’s nominees for election to the Coiste Gnótha but was never elected.28

This was a very busy time for Éamonn. Not alone was he working all day in the Corporation but in the evenings he was keeping all the records of the Clontarf Branch, attending meetings of the Central Dublin Branch, writing reports for the press, teaching students and publicising the events organised by both branches. He also found time for ‘his share of hurling practice in the Phoenix Park and enjoyed many a swim at The Bull, Dollymount’.29

He had a particular talent for arranging concerts and entertainments to attract new members to the League. He designed and distributed posters to promote the entertainments. His brother Michael remembered in particular that ‘when we used to go along at night posting up the concert posters in Clontarf, Éamonn led the way with the war pipes, keeping us going with grand old Irish airs’.30

All the members of the Kent family were musical and none more so than Éamonn. Michael later remembered buying ‘a cheap fiddle (7s. 6d.) to practise on at home … Éamonn took it up and could play “St Patrick’s Day” on it before I could at all.’31 Before long, Éamonn was proficient in both the fiddle and the whistle.32

Patrick Nally, a colleague in Dublin Corporation, sparked Éamonn’s interest in the union or uilleann pipes. Éamonn described the uilleann pipes as consisting ‘of bag, chanter, drones and regulator, the wind being supplied by a bellows placed under the right arm. It is an exceedingly sweet and very perfect instrument.’33 Nally arranged for Éamonn to purchase a set of pipes, and he immediately started to study them.34

He became a member of the Dublin Pipers’ Club (Cumann na bPíobairí), established on 17 February 1900. The objectives of the club were:

1. The cultivation and preservation of Irish Pipe Music;

2. The popularisation of the various forms of Irish Pipes; and

3. The cultivation of Irish dancing in connection with Irish pipe music.

One of the important patrons and, later, President of the club, was Edward Martyn; Martyn, together with William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory, had previously established the Irish Literary Theatre. The club held public musical evenings each Friday night, promising aspiring members that:

Irish Dancing, Fiddle, Flute and Pipe-playing are practised. Pipers and other musicians visiting Dublin also attend and enliven the proceedings. Irish, the official language of the Cumann, is spoken as much as possible on these occasions and is also used largely in correspondence. Pipers, both amateur and professional, are supplied to concerts in any part of the country if reasonable notice be given to the Hon. Secretary. An index of pipers is kept, containing a record of all known pipers, at home and abroad, living and dead.35

Characteristically, Éamonn set about researching the history of the pipes and promoting them publicly by every means possible. He also gave talks, illuminated with magic lantern slides,36 and wrote a set of articles on the history of the pipes from their origins in ‘the simple reed such as children construct for themselves from the rushes that grew by the river banks’, through their development in the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.37 Éamonn did not confine his enthusiasm for the pipes to the island of Ireland. Correspondence with The Sphere newspaper in London, in December 1903, confirmed the paper’s intention to use Éamonn’s article on the Irish bagpipes and ‘to pay for it and for the photographs at the ordinary rates’.38

In the text of a pamphlet written by Éamonn, the club promised that ‘any person with good lungs and fair musical capacity can become fairly proficient in six months’.39 For those lacking Éamonn’s musicality and enthusiasm, this seems optimistic, but in his notebook, Éamonn identified the problem and set about finding a solution.

Gentlemen often expressing a desire to learn the Pipes have been prevented by not meeting with a proper Book of Instructions, which has induced the author to write the following Treatise, which, it is presumed, with the favourite Collections of Tunes added thereto, will be acceptable to the Lovers of ancient and Pastoral Music.

The unpublished text provided pages of detailed instructions on everything the aspiring piper needed to know. The Pipers’ Club itself provided tuition for student pipers and, in his address as Secretary to the AGM on 27 February 1903, Éamonn remarked that the class ‘left no excuse to those who were eternally complaining that they could not get tuition on the instrument’.40

Éamonn also put his considerable organisational skills at the disposal of the new club. As its Honorary Secretary, he organised the meetings of the club and took the minutes in Irish. ‘He was in constant demand as an adjudicator at both pipe and fiddle competitions,’ recalled his wife, Áine.

Éamonn and Áine’s growing relationship and their joint interest in the pipes was typical of the cross-fertilisation of interests between members of the Gaelic League and the other organisations committed to the preservation of all things Gaelic. In many cases interests merged as they did when, on 21 October 1901, Éamonn appeared on stage as the blind piper in Douglas Hyde’s play, Casadh an tSúgáin, in the Gaiety Theatre. The play, which was the first in Irish to be presented in a Dublin theatre, was produced by the Irish Literary Theatre.41 The tune Éamonn played during the play was ‘The Lasses of Limerick’.

The Pipers’ Club was also closely associated with the Oireachtas of the Gaelic League,42 which comprised musical and Irish-language competitions, and, on 28 May 1903, the club’s members were praised in the League’s newspaper, An Claidheamh Soluis, for ‘showing us unmistakably that the instrument and the musicians to whom Irish–Ireland owes the preservation of its best airs are not yet dead’.43

Éamonn used every opportunity to promote his interest in the pipes and his commitment to the Irish language. A colleague in the Gaelic League remembered a time, in 1902 or 1903, when ‘there were droves of young enthusiastic Gaels going off to Aran and elsewhere to “perfect themselves” in Irish’. A group of these men set off, ‘to become native speakers in a fortnight’. Sadly disillusioned with their progress, they were returning to Dublin through Galway. Hearing of their arrival in Galway, Éamonn joined them. ‘With the skirl of the pipes’, Éamonn solemnly preceded them through Eyre Square and all the way to the station. Heads were popping, children running alongside and everyone gasping at the sight. The young Irish students ‘would have been glad if the ground opened up to swallow [them], or if they could have wrung Éamonn’s neck’. At the station, Éamonn marched up and down until a cheer was raised as the train moved off.44

Although he had left County Galway while just a small child, Éamonn came to love the county as an adult. He spent many holidays in Connemara, adopted the Connaught dialect, and always thought of himself as a Galway man. In a speech he gave to the Clontarf Branch of the Gaelic League, he described his first visit to Galway as a Gaelic Leaguer. He recounted how:

Whenever a Gaelic Leaguer enters [the village of] Menlo, he finds himself surrounded by a chattering crowd of children – chiefly boys. Give one a penny and he’ll tell a story or recite a poem with an accent and pronunciation that will fill you with delight as well as envy. Someone once remarked in surprise that in France even the little children speak French fluently. Wonderful. In Menlo the little children know more Irish than all the members of the Craobh Chluaintairbh put together.

With a naïve delight, common among his fellow Gaelic Leaguers, he described how he would cycle out along the coast, calling out in Irish to all those he met. He often took the opportunity to talk to little groups of youngsters galloping up bóiríní (little roads) from the sea with loads of seaweed – ‘curious unsophisticated youngsters they are, ragged and rough and all browned by the sea and wind. Wind from the Atlantic.’

The women he met were ‘fine, stout, rosy cheeked, weather beaten dames’. He described one young woman

… as she crossed a rock bearing in her hand a pail of water from the well. Her hair and eyes were black; a small dark shawl was thrown over her blue bodice. And a pair of bare feet projected from beneath the usual red petticoat, the contrast being highlighted still more by a white apron partly tucked up round the waist. There was something gypsy-like in her love of bright colours and her taste in selecting them. It struck me at the time that many of our fine ladies could have learned a lesson in dress from that poor hard working, supple, active, graceful country woman.45

One wonders whether the gently reared and well-shod ladies in his Dublin audience would have shared his enthusiasm!

In the early years of the century, the Gaelic League and the Pipers’ Club provided their members with a very active social life filled with music, song and dance. These were ideal opportunities for young men and women to meet and develop relationships based on deep mutual interests. The League was particularly attractive to women because it accepted members irrespective of gender.

Frances O’Brennan (who adopted the name Áine) was the youngest of the four daughters of Frank O’Brennan and his wife Elizabeth (née Butler). Áine’s family had nationalist tendencies on both her mother’s and her father’s side: her father, who died before she was born, was a Fenian, and her mother’s father was believed to have been a member of the United Irishmen.46

Áine, like her future husband, was one of the new generation who benefited from the Intermediate Education Act of 1878. Although initially confined to boys, the provisions of the Act were extended to girls in the face of opposition from the IPP and the Roman Catholic bishops – this followed the intervention by a deputation led by women’s rights campaigner Isabella Tod. Among the schools to benefit from the new legislative environment was the Dominican College in Eccles Street which Áine, together with her sisters Mary, Kathleen and Elizabeth (Lily), attended. Shortly after leaving school, Áine joined the Gaelic League and it was on a League outing to Galway, when Éamonn was nineteen and Áine twenty, that they met for the first time. They journeyed back from Galway together and, not long afterwards, Áine also joined the Pipers’ Club where she became Treasurer.47

Their relationship blossomed slowly at meetings of the League and the Pipers’ Club, on walks in the country and by the seaside. In August 1903, Éamonn and Áine kissed for the first time on the strand at Shankill, County Dublin. ‘Kisses never were sweeter,’ Éamonn later remembered, as he lay on the grass with Áine looking down into his face on ‘a magnificent, warm, sunshiny August day’.48

In the manner of the time, they corresponded very regularly – and Áine kept Éamonn’s letters, although he does not appear to have kept hers! Éamonn’s letters were bilingual – frequently starting in Irish and progressing in English. That same August, 1903, Éamonn was holidaying as usual in Connaught and wrote regularly from O’Sullivan’s Hotel in Spiddal and from the Hotel of the Isles in Gorumna. Missing her, he sent her railway vouchers to join him at the Connacht Feis.

At the time Éamonn was still living in the family home in Clontarf. Áine was living with her mother and sisters off the South Circular Road, at Dolphin’s Barn, and working at Messrs Cooper and Kenny, Auditors and Accountants, in 12 College Green, just up the road from Éamonn in Dublin Corporation’s municipal buildings.49