16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

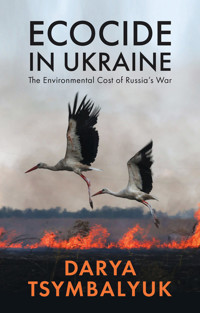

Russia’s war on Ukraine has not only destroyed millions of human lives, it has also been catastrophic for the environment. Forests and fields have been burned to the ground, animal and plant species pushed to the brink of extinction, soil and water contaminated with oil products, debris, and mines. On a single day in June 2023, the breached Kakhovka Dam flooded thousands of kilometres of protected natural habitat, as well as villages, towns, and agricultural land. The devastation of biodiversity and ecosystems across Ukraine has been immeasurable, long-lasting and its consequences stretch beyond national borders.

In this poignant book, Ukrainian researcher Darya Tsymbalyuk offers an intimate portrait of her beloved homeland against the backdrop of Russia’s war and ecocide. In elegant and moving prose, she describes the damage to the country’s rivers, the grasslands of the steppes, animals, insects, and colonies of birds, as a result of Russia’s ground and air operations. Alongside the everyday experiences of people in Ukraine living with the environmental consequences of the war, we share Tsymbalyuk’s own reckoning with the changing nature of cherished places and the loss of familiar worlds caused by the ongoing Russian invasion.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Table of Contents

Biography

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Note on Transliteration

Preface

Notes

Chronology

Map

1. Water

Waterflows

The other death of a flagship

Pieces of the world

Living and dying in the water

The weight of water

Swimmers

Notes

2. Zemlia

Zemlia: land, soil, earth, ground

The meanings of bread

The life of bread

After the occupation

A landmine detonates in the woods

Architecture of survival

A birch mouse in the steppe

Notes

3. Air

The smell of the war

Air quality

Climate crisis

Living in the air

Shelters

The sky above Ukraine

Notes

4. Plants

Horse chestnuts in spring

Vegetal cultures

The list

Meeting on the edge

Entangled extractions

Sheltering life

Inhabiting destruction

Black dead trees standing

Horse chestnuts in autumn

Notes

5. Bodies

Bodies as finitude

Frontline encounters

Cats, dogs, and other nonhuman companions

Bovine stories

Askania-Nova

Horses in Avdiivka

The great flood

Endangered and endemic

Beasts of war-time tales

Sediment of stress

Bodies loved, bodies remembered

Violets

Notes

6. Energy

Targets

Coal is the heart

Half-life of nuclear colonialism

Buh carnations

Joy and grief of the river

Lifelines

Notes

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Biography

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Note on Transliteration

Preface

Chronology

Map

Begin Reading

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

ii

iii

iv

v

vi

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

49

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

89

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

185

186

187

188

Darya Tsymbalyuk is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Chicago. Her work explores narratives about environments, multispecies worlds, war and displacement, embodied knowledge, and the entangled colonial histories of Ukraine. Tsymbalyuk’s writing has appeared on the BBC Future Planet and openDemocracy platforms, among many other publications. In addition to research and writing, she also works with images through drawing, painting, collage, and video essays.

Ecocide in Ukraine

The Environmental Cost of Russia’s War

Darya Tsymbalyuk

polity

Copyright © Darya Tsymbalyuk 2025

The right of Darya Tsymbalyuk to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2025 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6251-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024946046

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Dedication

For my parents, Victoria and Anatoliy

Acknowledgements

I wish the subject of this book and the need to write it had never existed. The book is a response to violence. The idea of writing it grew unexpectedly after an email from Inès Boxman, then an Editorial Assistant at Polity Press, and the manuscript would not have come into being without Inès’ understanding of what I was trying to articulate in my stories. When leaving Polity, Inès kindly placed me in the care of Louise Knight and Olivia Jackson, to whom I am grateful for their thoughtful guiding of the book to completion.

In her initial email to me Inès mentioned a short essay on mushroom picking and landmines I wrote for IWMpost in 2022, following my short visiting fellowship at the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna in August–September that year. From that moment on, the support of IWM has been central to my ability to work on this book. In summer 2023, I received funding from the ‘Documenting Ukraine’ scheme at IWM, which allowed me to spend three months in Ukraine, conducting interviews and visiting the places I was writing about. The manuscript then was completed during a visiting fellowship at New Europe College, Bucharest, funded by ‘IWM for Ukrainian Scholars’. I am especially grateful to Katherine Younger and Mariia Shynkarenko at IWM for having faith in my research and in this book in particular over the past two precarious years.

The book would not have been possible without two short fellowships: an Early Career Fellowship, ‘Inclusion, Participation and Engagement’, at the School of Advanced Study, University of London (October 2023–February 2024), and the already mentioned visiting fellowship at New Europe College, Bucharest (March–July 2024). These fellowships not only allowed me to fully focus on writing the manuscript but also helped me to sustain myself as a migrant early career scholar. The fellowship at the School of Advanced Study focused on pushing the boundaries of disciplines, and I am grateful to the School for its openness to and encouragement of my writing practice, as well as to the readers of parts of my first chapter, especially Kevin Amoke, Helen King, and Charlotte Rudman, for their generous feedback. I am also grateful to New Europe College for supporting me in the completion of the manuscript and discussing parts of it during one of the College’s weekly seminars.

Academic fellowships allowed me to focus and reflect, but at the heart of the book lie the months I spent in Ukraine. I am grateful to so many people there: Inna Tymchenko and Maryna Romanenko for welcoming me in Mykolaiv and introducing me to environmental networks; Halyna Drabyniuk at Yelanets Steppe Nature Reserve for allowing me to experience and understand the steppes more deeply; Kostiantyn Redinov at the Kinburn Spit Regional Landscape Park for making me travel to the Kinburn spit in my imagination and introducing me to the love of birds through his books and stories; Natalia Korinets at the Askania-Nova Biosphere Reserve for her stories of the Kherson steppes and the animals who inhabit them; Inna Tymchenko, Diana Krysinska, Oleh Derkach, and Natalia Iemeliantseva for taking me on a once-in-a-lifetime trip to meet voloshka pervynoperlynna, a plant endemic to the steppes of Mykolaiv; Oleksii Vasyliuk at the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group for helping me understand the most pressing concerns of environmentalists today; Sofia Sadogurska and Bohdan Kuchenko for welcoming me at Ecoaction; Tetiana Topalova for taking me around the Mykolaiv ecostation; Ivan Rusev at the Tuzly Lagoons National Nature Park for his stories about dolphins and porpoises; Serhii Vasylenko, Olena Sychuhova, Iulia Zavods’ka, and Father Taras Mel’nyk for helping me to search for stories all over Ukraine; Nadiia Ivanova, Olena Korsuns’ka, and Hryhorii Tkachenko for helping me understand the hardships of farming during the war; Borys Dudenko, diadia Tolia, the workers of Mykolaiv Vodokanal, and Dmytro Myroshnychenko at the Mykolaiv Combined Heat and Power Plant for allowing me to see the hard work of maintaining critical infrastructure; Viacheslav Pluhovyi, Ievhen Honchar, Natalia Bratus’, Tetiana Zaiets’, Volodymyr Vendriukhovskyi, pani Oksana, and pani Tetiana at Snihurivka and Ivano-Kepyne for sharing their poignant stories of the Kakhovka disaster; Natalia Kushnirenko for showing me her house and precious tomatoes; Liudmyla Opanasiivna at the library of the Hryshko National Botanical Garden for helping me to trace steppe plants in books; Serhii Koriaka for taking his time to speak to me on the phone about demining; Inna Kryvko for sharing reports of environmental destruction; Bohdan Hrytsevych and Tetiana Koval’chuk for showing me Buh carnations and other inhabitants of Buzkyi Gard; Oleh Dudkin for talking to me about bird conservation efforts across Ukraine (and who sadly will never see this book); Olha Stepanenko for stories of vulnerability and resistance; Victoria D. for the beautiful map; and all the drivers of buses, minivans, and trains that carried me across the land, all the critical infrastructure workers for making water in the taps run and electricity light the bulbs, and the Ukrainian Armed Forces for continuing to keep people and places safe in the darkest hour. While I have not directly reached out to Serhii Lymanskyi in relation to this manuscript, the memories of my trip to Kreidova Flora Nature Reserve in 2019 continue to shape my understanding of the environmental impact of the war.

The process of writing this book was anxious and intense, and I am especially grateful to El Crabtree and Anu Nael, as well as the two anonymous reviewers, for taking the time to read the first draft and provide me with generous comments. I would also like to thank Olga Voinalovych for her feedback and encouragement. I am deeply grateful to my partner Ahmed Abouzaid for his patience and support in reading a dozen drafts and for repeatedly persuading me that I could tell this story. Finally, I am indebted to my mother, Victoria Tsymbalyuk, for documenting how beautiful the spring in Kyiv is even during the Russian invasion, for always carrying food for birds, cats, and dogs, for teaching me how to listen to the river, and for being the most amazing companion on my trips across Ukraine; and to my father, Anatoliy Tsymbalyuk, for joining me on my first trip to a nature reserve to study the environmental impacts of the war back in 2019, for sending me photos of a rooster living next to him, of (often burned) forests and fields, and of his newly found friend Dyvan the dog, and for making me realize how much love I will always have for the south.

Note on Transliteration

Transliteration of Ukrainian and Russian languages follows the Library of Congress romanization table, unless there are established spellings of certain proper names, i.e. cities (Yuzhne, Yuzhnoukrainsk, etc.) and authors (Yevhenia Podobna, etc.)

Preface

I was not in Ukraine when, on 24 February 2022, Russia escalated its almost eight-year-long war on Ukraine to a full-scale invasion. When I finally returned to see my family for the first time since the invasion, crossing from Poland on a night train to Kyiv, I could not stop looking out of the window. I wanted to imprint in my memory every little tree, every bird echoing a cloud, every glimpse of the river which kept disappearing all too quickly. Nowhere do I experience such shimmering joy just by looking at things, just by being in a place, as I do in Ukraine these days.

It is from this place of love that my sorrow comes too. Out of the train window, villages were disappearing too quickly for me to be able to read their names and I kept turning my head in hope of deciphering them. While writing this book, I thought a lot about how we learn about things only when they disappear, and the deep injustice of such learning. In the book, I call this process an episteme of death. The episteme of death put a morbid spotlight on certain species endangered by the war, on habitats and ecosystems, and on Ukraine’s communities overall.

When the environmental cost of Russia’s war on Ukraine is discussed domestically and internationally, it is often engaged through the lens of ecocide, which is also reflected in the title of this book. While today the term ‘ecocide’ is being applied to a wide range of crimes of environmental destruction, it originally emerged in the context of US herbicide warfare in Vietnam.1 In 2021, an Independent Expert Panel at Stop Ecocide International, a global campaign fighting to amend the Rome Statute at the International Criminal Court, defined ecocide as ‘unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts’.2 The Ukrainian state is also working on adding ecocide to the Rome Statute as a fifth core international crime.

On the domestic level, Ukraine is one of little more than a dozen countries in the world that have an article for ecocide in their criminal code (Article 441). In 2021, just before Russia escalated its war to a full-scale invasion, the Specialized Environmental Prosecutor’s Office was established in Ukraine. Today, this Office investigates cases of ecocide, and it served its first notices of suspicion in February 2024. Among the cases that the Office works on, perhaps the most well-known is the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, which, according to Jojo Mehta, co-founder of Stop Ecocide International, is ‘a textbook ecocide case’.3 In the last couple of years, ecocide has become central to Ukraine’s understanding of the war’s environmental impact as entangled with other war crimes committed by Russia, as well as to Ukraine’s understanding of justice. The evidence for ecocide in the country is painstakingly collected by prosecutors, investigators, forensic specialists, and environmentalists, often in life-threatening circumstances.

The lens of ecocide sets the frame of my work. However, I am not a legal scholar, and my intention in this book is not to provide evidence of the crime of ecocide in specific cases. Here, my focus is on tracking how experiences of witnessing and living through ecocide change one’s understandings of environments and one’s home(land). I argue that the impacts of ecocide spill beyond specifically designated (legal) cases, into the most intimate and everyday realities. As a result, places which were once familiar now hold danger. To very different degrees of violence, the war displaces everyone, not only the people who have fled from it. Even if you do not evacuate but remain in your hometown, suddenly you find yourself in a different world, where the river stores unexploded bomblets, and the forest trail might be mined. I have been in a privileged position, living abroad in places removed from direct danger and unaffected by severe shortages of water and electricity. Yet, even at such a distance, the Russian invasion also changed my understandings of environments. Shelterbelts, skies, corridors, and walking paths feel different. It is these re-mapped spatial relations that I trace in this book. What are the changing meanings of water, bodies, air, land/ground/soil, plants, and energy? How does the war disrupt, violate, and condition life and survival? What places could serve as potential places of shelter? What is this changing world of ‘home’? I also argue that only through an environmental lens can we begin to comprehend the scale and anguish of the devastation, the loss of whole worlds inhabited by plants, animals, rocks, people, and others, caused by Russia’s war.

In Ecocide in Ukraine, I do not aim to provide an exhaustive overview of the environmental destruction in Ukraine and beyond its borders. Such a comprehensive account would be impossible, as the data are often scarce, and, most importantly, the war is not over. In the future, other scholars will take on this task and will be better equipped to write an overview from a position of analytical and historical distance. Instead, I invite you to approach Ecocide in Ukraine as a situated account that speaks among other voices and does not aim to represent but, in the words of Trinh T. Minh-ha, ‘speaks nearby’.4 Here, the act of writing is a process of understanding and of piecing the fragments together, not necessarily to make sense – it is impossible to make sense of war – but to pause and think, and to invite readers to pause and think with me.

These days Ukraine is frequently featured in the news through horrific images of violence, and these experiences are at the heart of this book too. Yet, here, I also want to tell you about Ukraine as a place which is loved, about Ukraine as a home, for humans and other species. While based on research, this book is also an imperfect and personal document, and my knowledge is rooted in places familiar to me. This past year of working on the manuscript ironically marks my life as divided into two exact parts: the one that I lived in the south of Ukraine, and the one that I have lived between many other places away from the south. Russia’s war deepened the pull of home for me; it made me constantly think of disrupted living patterns and of the many returns – of people, water, birds, and stories. Hence, I write more about the south of Ukraine than about other regions.

Yet, I do not intend the personal to be exclusive. As we know all too well, environmental destruction is not contained by regional or national borders: the rain that fell from the radioactive Chornobyl clouds contaminated lands a long way from Kyiv Oblast, the epicentre of the 1986 nuclear catastrophe. The impacts of Russia’s war on Ukraine are also felt across the globe, from food shortages to the loss of biodiversity and the pollution and militarization of the Black Sea. Ukraine’s contribution to the international legal campaign to amend the Rome Statute will have implications in places and contexts far beyond Ukraine too. Finally, experiences of living in war ecologies are not unique to Ukraine, and while writing this book I have been following with horror the multitude of past and present stories from other places devastated by wars and violence.

In writing the book I have relied on interviews, conversations, reports, journalists’ investigations, social media posts, and my journeys across Ukraine (photos from these journeys open the chapters of the book), and I am especially grateful to everyone on the ground who is documenting the Russian invasion. Most of this documentary work is done in Ukrainian, usually in life-threatening conditions, and is often not available in other languages. I build on this knowledge that shapes my understanding of the situation on the ground to share with readers who might not know much about my homeland. This book is a form of distant witnessing; not a first-hand account of events, but a re-telling, a re-piecing, and a meditation. This experience of witnessing, even from afar, is anchored in the cultural thickness of stories and images about storks, feathergrass, reedbeds, and rivulets of the Lower Dnipro. Without an understanding of the long histories of shared lives contained in these stories and images, it is not possible to comprehend the full extent of the loss caused by Russia’s ecocide; therefore, in addition to environmental reports, data, and witness accounts, in Ecocide in Ukraine I also rely on poems, films, and paintings.

The following chapters present the diverse stories I have collected, while trying to understand how my homeland is changing and how people and other species have responded to these changes. The stories are arranged thematically, but just as it is sometimes hard to tell where the aquatic worlds end and the terrestrial worlds begin, the stories in this book often flow across several chapters, with each chapter bringing different elements into focus. These stories are also often fragmented, just like the places they come from, now shattered by the war. While shattered, they are still lived places, beautiful places, and beautifully lived places.

In one of the videos from Kherson, flooded as the result of the Kakhovka Dam disaster, a woman is asked whether she will be evacuating.5 Liudmyla replies that she will be staying, using the word perebudemo, where the suffix pere- translates as over-, and budemo is a conjugation from the verb buty, to exist, to be, to stay. In Liudmyla’s answer perebuty means to wait (for something to pass), but in Ukrainian it also contains a possibility of over-staying, over-existing, over-being. It is this over-existence of all those on the ground, in the waters, and in the air of my attacked homeland that keeps those worlds living, and it is about them that I have been thinking while writing this book.

October 2023–July 2024

Notes

1.

For the history of the emergence of the term ecocide see David Zierler,

The Invention of Ecocide: Agent Orange, Vietnam, and the Scientists Who Changed the Way We Think about the Environment

(University of Georgia Press, 2011).

2.

Stop Ecocide International, Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide: Commentary and Core Text, June 2021,

static1.squarespace.com

.

3.

Anna Ackermann, ‘In conversation: Stop Ecocide co-founder Jojo Mehta’,

London Ukrainian Review

, 4 March 2024, london

ukrainianreview.org

.

4.

Nancy N. Chen, ‘“Speaking Nearby”: a conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha’,

Visual Anthropology Review

, vol. 81, no. 1, 1992, pp. 82–91.

5.

You can watch the video at the Suspilne Mykolaiv YouTube channel,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=am407edLxME

.

Chronology

Relevant key dates of Russia’s war on Ukraine (2014– )

February 2014

Start of the Russian occupation of Crimea

April 2014

Start of the war in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts

24 February 2022

Russia launches full-scale invasion of Ukraine

24 February–2 April 2022

Russian occupation of the Chornobyl Zone of Exclusion and Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant

February–May 2022

Russian siege of Mariupol

4 March 2022

Russian occupation of Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant

2 April 2022

Kyiv Oblast is fully de-occupied

September 2022

De-occupation of Kharkiv Oblast

11 November 2023

De-occupation of Kherson

6 June 2023

Destruction of the occupied Kakhovka Dam

Map of Ukraine with selected locationsMy thanks to Victoria D., who drew up the map to reflect the various locations that are relevant to the book.The map is reproduced with her kind permission.

1Water

Waterflows

In my childhood spent in and around Mykolaiv in the south of Ukraine, no matter what place we lived in, there was always water nearby. Since then, whenever I moved to a new place, locating the nearest big water was a way of making that place a home. In cities without big water, I feel disoriented, out of place. Water is a lifeline, a lifeflow of my geography.

In Mykolaiv water meets water: the river Inhul and the Southern Buh river meet each other and become the Buh estuary, then becoming the Dnipro-Buh estuary or lyman as we say in Ukraine. A constant pull to the sea is inscribed in Mykolaiv’s origin story. It was strategically built as a shipyard as part of the colonization of the south by the Russian Empire. Ever since its inception, Mykolaiv has always been thinking about the sea. When I look at the giant map of Ukraine in the corridor of our apartment in Mykolaiv – the map I mostly study these days to locate villages and towns that were shelled the night before – all rivers, all water, seem to be flowing south to the Black and the Azov seas. Like the palms of two hands the seas are holding the cartographic image of Ukraine.

The south for me is this openness of space unfolding towards the water, the kind of openness that makes the windy air in my home village of Velyka Korenykha taste like apples, sweet and nourishing. Once upon a time there were vast grasslands of the steppe in the south, which were exhaustively ploughed and replaced by monocrop agricultural fields. The plains are arid, but at some point(s) in the south they meet the water plains, the seas. Following the trembling shoreline of the encounter between the land and the water on a map, I trace fickle lymans and sandy spits, charged with intense life. The Azov-Black Sea coastline has been home to more than 10,000 species of flora and fauna, and 8 million birds pass through the Azov-Black Sea migration route twice per year.1 Seeing the land from above, birds follow landmarks to find their way; they follow rivers becoming lymans and falling to the sea.

Lyman is an ecotone, an overlap of ecosystems that brings about higher biodiversity. It is also an environment that is constantly changing. I intentionally keep the Ukrainian word in this text, as it is a word that sounds salty, and a word that holds a precious promise of the south with its open and endlessly unfolding space. My wall map of Ukraine is very big, and tracing the lines on it with my hand, I linger in places, on particular lymans, holding a finger on each spot to hold it in my mind. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has rendered many lymans inaccessible and militarized, such as the Molochnyi lyman, the shores of which have been occupied and used as a training ground for the Russian military. The Molochnyi lyman is a fickle ecosystem between the river Molochna and the Sea of Azov, a home to 20,000 wetland birds.2

As with many other things, the war accentuated the waterflows in my perception and understanding of the environment. It made them more palpable, carving them deeper in my mental map of the region. War violently re-maps the space, where some territories, terrains, and nodes beat with pain or danger, or sometimes with the hope of refuge. When I am thinking of the south of Ukraine, following waterways in my imagination, these waterways ache. Many of them have been turned into borders between different kinds of killing. Hence, the left bank of the Dnipro river in the Kherson, Dnipropetrovsk, and Zaporizhzhia oblasts remains occupied by the Russian military, where people are subjected to fear, torture, and persecution, while the right bank lives under incessant bombardment from the occupied territories.

Kakhovka Dam was occupied by Russia at the beginning of the full-scale invasion in 2022, and it remains occupied to this day. In the early hours of 6 June 2023, the occupied dam breached. The Kakhovka water reservoir was one of the largest in Europe, holding 18.2 km3 of water. The water from the reservoir flooded settlements on both banks of the Dnipro, as well as on the banks of other connected rivers. According to an assessment by the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, as a result of both flooding and shallowing, the disaster impacted wildlife over an area of at least 5000 km2.3 More than 60,000 buildings were flooded.4 No independent experts have been allowed into the territory occupied by Russia to conduct on-site investigation, but a remote investigation by the New York Times suggested that the dam was destroyed by an explosion from the inside.5 In Ukraine, the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam is being prosecuted under the law against ecocide, defined in Article 441 of the Criminal Code as ‘mass destruction of flora and fauna, poisoning of air or water resources, and also any other actions that may cause an environmental disaster’.6 In the aftermath of the disaster, on the right bank of the Dnipro, which is controlled by Ukraine, volunteers helped to evacuate people and animals, navigating the streets on boats, looking for routes that would avoid submerged electricity poles or other architectural structures that were now underwater. On the occupied left bank, residents of flooded towns such as Oleshky and Hola Prystan were left on their own, and even prevented from being able to evacuate. During the first critical days there was no organized help from the Russian occupation authorities or international organizations.7 This resulted in a disproportionately higher number of deaths, though we still do not know the exact numbers. Since Russia’s occupation, the Dnipro river has become a line between different kinds of living and dying, sometimes between living and dying itself.

I follow the Dnipro on the map – the biggest river in Ukraine, flowing from Kyiv to Kherson. In the south the Dnipro meets the Southern Buh river, and together they form the Dnipro-Buh lyman. That is how the water from the Kakhovka reservoir also reached Mykolaiv and flooded some streets in my home village located on the Buh estuary – one of the few times I have ever seen the village mentioned on the national news, the other time being when a missile hit one of its apartment blocks.

On the map, I trace the Dnipro-Buh lyman to where it connects to the Black Sea through a 4–7.5 km strait between the resort city of Ochakiv and the Kinburn spit. The Kinburn spit, a narrow sandy stretch of land and an important stopover conservation site of the bird flyway, is still occupied by Russia; it is the only part of Mykolaiv Oblast which remains under occupation. The narrow strait that carries the water into the Black Sea was once busy with ships that, among other goods for export, carried grain, grown in Ukraine and so vital for global food security. The resort town of Ochakiv and the neighbouring villages of the Kutsurub municipality are regularly shelled. Just as with other territories of Ukraine that regularly come under fire, unless someone is killed the reports of the attacks usually appear as one line on the national news, and almost never make it to the international news: the daily horror is condensed to a single line or left invisible. The intention of Russia in attacking these places is annihilation. This erasure is indirectly strengthened when even the quiet whisper about the horror vanishes into silence.

The other death of a flagship

What remains though are the missile shells and drones that fly across the lyman and the Black Sea, many of which end up in the water. Russia has extensively militarized the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. The Black Sea capes, such as the Chauda Cape in Crimea, and the military ships located in the region, are used for launching missiles and drones against mainland Ukraine. Marine biologist Sofia Sadogurska observes that these launches result in wave blasts and chemical pollution, including oil spills.8

On 13 April 2022, the Russian guided missile cruiser Moskva, the flagship of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, was sunk by the Ukrainian Armed Forces. In an ironic twist of fate, the cruiser was built in my hometown Mykolaiv in the 1970s, when Mykolaiv was one of the centres of shipbuilding in the Soviet Union. It was also repaired there in the 1990s after Ukraine had become an independent state. Mykolaiv Shipyard, where Moskva was constructed, has been extensively shelled by Russia. The shelling brought environmental destruction through debris and chemical pollution.9 When I was at home in July 2023, another missile attack was launched against the area of the city where the shipyard is located. Several residential houses were hit instead, killing two people and injuring eighteen. We heard the blasts from our corridor, the sounds travelling through the river water with a higher intensity of transmission, right into the open windows of the July heat.

The cruiser Moskva brought a lot of suffering to the world, including environmental damage. It was engaged in Russia’s imperial invasions of Georgia, Syria, and Ukraine.10 Even after its sinking, it continues to be deadly. In the north-western part of the Black Sea, at a depth of 15–50 metres, there are vast stretches of red seaweed between sand dunes. This is the world’s largest known site of the red algae Phyllophora. There, at the bottom of the sea, nest algae formations the colour of dried blood. Within them there are the shimmerings of dozens of other living beings, at least forty species of fish and approximately 100 species of invertebrates, many echoing the algae with red or purple colouring, all together forming the moving and breathing flesh of the sea bottom.11 There is a probability that the Moskva sank near this marine reserve, known as the Zernov Phyllophora Field, though only an investigation would be able to show exactly where.12

Video footage of the Zernov Phyllophora Field, which I am watching to learn more about the reserve, was made available in 2017 by the EMBLAS II project.13 Between 2014 and 2020, transnational EU/UNDP EMBLAS projects were set up to monitor the Black Sea environments and help improve their protection. I study the Summary of EMBLAS Project findings, gaps and recommendations published in April 2021 alongside other research.14 A fragile hope for the recovery of the Black Sea can be seen in these reports. According to J. Slobodnik et al., before the Russian full-scale invasion, the Black Sea beaches were the worst in Europe when it came to pollution by single-use plastic.15 The Black Sea was also dangerously polluted with pharmaceuticals. Still, the scientists reported a gradual improvement, including in the Zernov Phyllophora Field. The fragility of this hope is mirrored in the fragility of the research itself, as one realizes the impossibility of working on it today. Since the Russian full-scale invasion, transnational research and environmental monitoring of the Black Sea have been extremely limited and, in many cases, totally impossible.

Meanwhile, in the North Sea, a transnational research team studied a shipwreck from the Second World War. Edmund Maser et al. discovered that explosive substances were still leaking into the sea eighty years later, and were present in the fish and mussels that lived around the shipwreck.16 Shortly after its sinking, Ukraine recognized Moskva’s shipwreck as an underwater cultural heritage. We can only hope that one day marine biologists will be also able to monitor how the Moskva remains deadly even after its death as a Russian flagship.

Pieces of the world

Moskva might be the biggest piece of military litter in the Black Sea, but it is not the only one, as there are drifting mines, missiles, bombs, drones, and their remnants. The Kakhovka Dam disaster resulted in further significant littering of the sea, and of rivers and estuaries as well. What could be seen with a human eye from the shore was documented in several videos uploaded by the environmental organization Green Leaf, based in Odesa. The first video, published on YouTube on 9 June 2023, three days after the breach, shows houses and roofs floating in the water.17 The description says that the video was filmed near the city of Yuzhne, located north of Odesa. Another video was recorded on 11 June and features Vladyslav Balinskyi, the head of the Green Leaf organization.18 In the video, he walks along the shore of Sobachii beach in Odesa, following the broad trail of a bulky pile of driftwood and reeds scattered on the sand or floating on the water near the shore. Among the driftwood there are also pillows, doors, construction parts, buckets, the body of a dead fish, and entangled plants pulled out by their roots. All of this had been washed ashore following the collapse of the Kakhovka Dam and the subsequent flooding of villages and cities, the force of the water carrying shattered and displaced pieces of the world. One of the witness videos even documented a scared roe deer who had been carried to the Odesan shores on an island of reeds.19

In the 11 June video, as Balinskyi walks he comments on water samples he has taken and on the abnormal freshness of the sea water. He also mentions the presence of frogs. As he follows the driftwood trail, the camera catches local beachgoers, people swimming in the polluted water, which in addition to potentially dangerous organic matter also carries the risk of drifting mines. In his commentary, Balinskyi keeps repeating that what he sees are pieces of someone’s life. The pile of litter on the seashore is a temporary record of the violence against people whose lives have been shattered, against plants and animals whose habitats have been washed away, and against riparian and marine environments. In a later video by Green Leaf, posted on 16 June, we see how this organic record solidifies into litter dunes, as the water around them starts to bloom with an intense green colour in a process called eutrophication.20

After the Kakhovka disaster, some houses and their remnants drifted into the open sea, all the way down to Odesa; others did not move but were utterly devastated. I have seen some of the latter in the villages on the shores of the Inhulets river in Mykolaiv Oblast. Though many remained in place, their worlds had been hollowed out by the big water and filled with the contaminated, toxic-smelling mud that covered personal memories and family secrets, reaching every pocket, every drawer, every corner. Many of the houses flooded in the Kakhovka disaster were made from saman or adobe, a combination of uncooked clay, straw, and sand. This has been a traditional form of housebuilding in the south (and other regions) of Ukraine, as well as in many places across the world, a technique known globally as earth architecture. Raw clay, an essential component of saman, is especially vulnerable to destruction by water.