14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

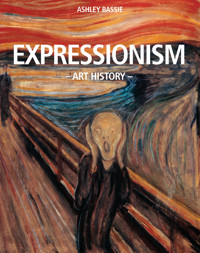

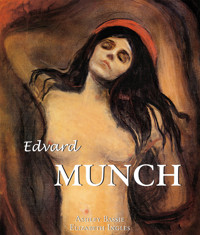

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), a Norwegian painter involved in Expressionism, was so attached to his work that he called his paintings his children, which is rather unsurprising given that they were deeply personal. Indeed, Munch expressed much of his own inner turmoil through his art, particularly in the earlier part of his career. He painted not what he saw, but what he felt when he saw it, allowing his morbidity and illness to imbue his paintings with a sombre tone. These darker paintings, including his famous The Scream, endured and would greatly influence German Expressionism.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 143

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Authors:

Ashley Bassie and Elizabeth Ingles

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-68325-636-6

Ashley Bassie and Elizabeth Ingles

Contents

What is Expressionism?

The Body and Nature

The Self and the Psyche

The Metropolis and Modernity

Vision and the Spirit

The End of Expressionism?

Edvard Munch

Biography

List of Illustrations

Landscape. Maridalen by Oslo, 1881. Oil on wood, 22 x 27.5 cm. Munch-museet, Oslo.

What is Expressionism?

Expressionism has meant different things at different times. In the sense we use the term today, certainly when we speak of “German Expressionism,” it refers to a broad, cultural movement that emerged from Germany and Austria in the early 20th century. Yet Expressionism is complex and contradictory. It encompassed the liberation of the body as much as the excavation of the psyche.

Within its motley ranks could be found political apathy, even chauvinism, as well as revolutionary commitment.

Expressionism’s tangled roots range far back into history and across wide geographical terrain. Two of its most important sources are neither modern, nor European: the art of the Middle Ages and the art of tribal or so-called “primitive” peoples. A third has little to do with visual art at all – the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. To complicate matters further, the word “Expressionism” initially meant something different.

Until about 1912, the term was used generally to describe progressive art in Europe, chiefly France, that was clearly different from Impressionism, or that even appeared to be “anti-Impressionist.” So, ironically, it was first applied most often to non-German artists such as Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse and Van Gogh. In practice, well up to the outbreak of the First World War, “Expressionism” was still a catch phrase for the latest modern, Fauvist, Futurist or Cubist art. The important Sonderbund exhibition staged in Cologne in 1912, for example, used the term to refer to the newest German painting together with international artists.

In Cologne though, the shift was already beginning. The exhibition organisers and most critics emphasised the affinity of the “Expressionism” of the German avant-garde with that of the Dutch Van Gogh and the guest of honour at the show, the Norwegian Edvard Munch. In so doing, they slightly played down the prior significance of French artists, such as Matisse, and steered the concept of Expressionism in a distinctly “Northern” direction. Munch himself was stunned when he saw the show. “Here is collected the wildest of what is being painted in Europe,” he wrote to a friend, “Cologne Cathedral is trembling to its very foundations.”

More than geography though, this shift highlighted Expressionist qualities as lying not so much in innovative formal means for description of the physical world, but in the communication of a particularly sensitive, even slightly neurotic, perception of the world, which went beyond mere appearances.

As in the work of Van Gogh and Munch, individual, subjective human experience was its focus. As it gathered momentum, one thing became abundantly clear – Expressionism was not a “style.” This helps to explain why curators, critics, dealers, and the artists themselves, could rarely agree on the use or meaning of the term.

Nonetheless, “Expressionism” gained wide currency across the arts in Germany and Austria. It was first applied to painting, sculpture and printmaking and a little later to literature, theatre and dance.

It has been argued that while Expressionism’s impact on the visual arts was most successful, its impact on music was the most radical, involving elements such as dissonance and atonality in the works of composers (especially in Vienna) from Gustav Mahler to Alban Berg and Arnold Schoenberg. Finally, Expressionism infiltrated architecture, and its effects could even be discerned in the newest modern distraction – film.

Historians still disagree today on what Expressionism is. Many artists who now rank as quintessential Expressionists themselves rejected the label. Given the spirit of anti-academicism and fierce individualism that characterised so much of Expressionism, this is hardly surprising. In his autobiography, Jahre der Kämpfe (Years of Struggle), Emil Nolde wrote: “The intellectual art literati call me an Expressionist. I don’t like this restriction.”

Vast differences separate the work of some of the foremost figures. The term is so elastic it can accommodate artists as diverse as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Egon Schiele and Wassily Kandinsky. Many German artists who lived long lives, such as Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Otto Dix and Oskar Kokoschka, only worked in an “Expressionist” mode – and to differing degrees – for a small number of their productive years.

Others had tragically short careers, leaving us only to imagine how their work might have developed. Paula Modersohn-Becker and Richard Gerstl died before the term had even come into common use. Before 1914 was out, the painter August Macke and the poets Alfred Lichtenstein and Ernst Stadler had been killed on the battlefields. Another poet, Georg Trakl, took a cocaine overdose after breaking down under the trauma of service in a medical unit in Poland. Franz Marc fell in 1916. In Vienna the young Egon Schiele did not survive the devastating influenza epidemic of 1918, and Wilhelm Lehmbruck was left so traumatised by the experience of war that he took his own life in Berlin in 1919.

Akerselva, 1881. Oil on cardboard, 23 x 31.5 cm. Private collection.

Garden with Red House, 1882. Oil on cardboard, 23 x 30.5 cm. Galerie Ars Longa, Vita Brevis collection, Oslo.

Garden with Red House, 1882. Oil on cardboard, 46.5 x 57 cm. Galerie Ars Longa, Vita Brevis collection, Oslo.

Old Aker Church, 1881. Oil on canvas, 16 x 21 cm. Munch-museet, Oslo.

It is easier to establish what Expressionism was not, than what it was. Certainly Expressionism was not a coherent, singular entity. Unlike Marinetti’s Futurists in Italy, who invented and loudly proclaimed their own group identity, there was no such thing as a unified band of “Expressionists” on the march.

Yet unlike the small groups of painters dubbed “Fauves” and “Cubists” in France, “Expressionists” of one hue or another, across the arts, were so numerous that the epoch in German cultural history has sometimes been characterised as one of an entire “Expressionist generation”.

The era of German Expressionism was finally extinguished by the Nazi dictatorship in 1933. But its most incandescent phase of 1910-1920 left a legacy that has caused reverberations ever since. It was a period of intellectual adventure, passionate idealism, and deep yearnings for spiritual renewal. Increasingly, as some artists recognised the political danger of Expressionism’s characteristic inwardness, they became more committed to exploring its potential for political engagement or wider social reform.

But utopian aspirations and the high stakes involved in ascribing a redemptive function to art, meant that Expressionism also bore an immense potential for despair, disillusionment and atrophy. Along with works of profound poignancy, it also produced a flood of pseudo-ecstatic outpourings and a good deal of sentimental navel-gazing.

Some of the most stunning products of German Expressionism came from formal public collaborations as well as intimate working friendships. There were elements of both in the groups most important for pre-war Expressionism, the Brücke (Bridge) and Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider), for instance. Fierce arguments were conducted and common ground was staked out in journals such as Der Sturm (The Storm) and Die Aktion (Action), as well as in the context of numerous group exhibitions. Others came from introspective loners working in relative isolation.

Crucially, this was also an age shattered by the crisis of a devastating technological war and in Germany, its most debilitating aftermath. The conflict and trauma of the period is inseparable from the forms Expressionism took, and ultimately, from its demise.

Girl Lighting a Stove, 1883. Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 66 cm. Private Collection.

The Author August Strindberg, 1892. Oil on canvas, 122 x 91 cm. Gift of the artist, 1934, Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

From Maridalen, 1881. Oil on cardboard, 20 x 30 cm. Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo.

The Body and Nature

This chapter examines the central importance, in many Expressionist works, of the relationship between man / woman and nature. The nude played a pivotal role in the Brücke’s practice, where it was often an idealised symbol of moral, physical and sexual liberation. The body and sexuality was differently cast in other Expressionist contexts, as further chapters will explore.

Expressionism is often subject to cliché and misunderstanding. It has sometimes been dismissed as an aberrant detour in the onwards march of European modernism. The influential American critic Clement Greenberg felt, for example, that Kandinsky’s work suffered as a result of the context from which it emerged: “Picasso’s good luck was to have come to French modernism directly, without the intervention of any other kind of modernism. It was perhaps Kandinsky’s bad luck to have had to go through German modernism first.”

At other times Expressionism has been over-dramatised as an irrational manifestation of a peculiarly Teutonic neurosis. More accurately, it has been described in terms of a “cultivated rebellion”. In order to understand the many forms Expressionism took in Dresden, Berlin, Munich, Vienna and numerous provincial outposts, it is useful to grasp what it was rebelling against.

In common with much of Western Europe, Wilhelmine Germany in the late 19th century was in a state of massive upheaval. The rampant effects of modern capitalism – industrialisation, urbanisation, rationalisation and secularisation – created ruptures in the social fabric that were not easily absorbed or contained. In spite of this, the process of Germany’s economic modernisation, supervised by an absolutist military state, was carried out with precision and discipline – even though these were qualities sometimes lacking in the monarch himself.

Traditional morality both relied upon and fed orderliness and the power of institutions: above all, the monarchy, the church, the family, school and the army. Paul Klee, a Swiss, satirised with cruel precision a particularly Prussian “virtue” – unquestioning obedience to authority – in an early etching. It shows a grotesquely fawning monarchist, ludicrous in his nakedness, bowing down so low before an apparition of a crown that he appears on the verge of toppling into the abyss.

Expressionism was a self-consciously youthful movement. The “Founding Manifesto of the Brücke” proclaims it clearly. It bears witness to the generation gap, which had widened to a gulf. In their age, the primary influence on young people was no longer parental, but increasingly social. The programme very clearly identifies “a new generation of creators” and “youth,” striving for “freedom of life,” as a group quite distinct from the “long-established older forces”.

Significantly, Kirchner’s call to youth was not unique. At this time, many young Germans were discovering group identities for themselves. After the turn of the century, numerous youth groups formed, the largest of which became the Wandervögel movement. Immersion in the German countryside as an antidote to the city was not just a recuperative measure. It was a whole ideology.

This encompassed urban workers’ associations seeking alleviation from city drudgery by means of invigorating country hikes, student organisations, Christian and Jewish groups, communities inspired by German paganism, ultra-nationalists as well as socialist pacifists, anarchists, vegetarians, those interested in Eastern philosophies, and all manner of others seeking reforming lifestyles. Britain’s “Arts and Crafts“ movement was a direct expression of the desire for a return to pre-industrial values, so it is not surprising that John Ruskin and William Morris were among the prophets often upheld by these groups. Jugendstil, iconographically and stylistically “youthful,” organic and anti-materialist, was often the nearest visual metaphor for this ethos.

In a large, highly stylised canvas by the eminent Swiss painter, Ferdinand Hodler (whose distinctive “parallelism” is also related to Jugendstil), the abstract concept of “truth” is given allegorical form in the figure of a gleaming female nude, whose light dazzles the draped male figures around her.

The widespread Freikörperkultur, naturism, or “Free Body Culture” movement, originated in this context. Most of these were middle-class movements, but they shared a desire to establish a principled independence from the crass materialism of modern life.

The foundation of groups such as the Brücke can be seen as part of this predominantly youthful German movement. They “belonged” to a new age that was not their parents’. This helps to account for their rejection of the public moral and spiritual values of the older generation. It also sheds light on other Expressionists’ imagery of youth.

There is more than a whiff of Nietzsche around Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s young, contemplative, ascending youth, for example. Its articulation of both the inwardness and the aspirational vitalism of the generation moved many who saw it.

Music on Karl Johan Street, 1889. Oil on canvas, 102 x 141.5 cm. Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich.

Morning (A Servant Girl) (detail), 1884. Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 103.8 cm. Private Collection, Bergen.

Portrait of Karl Jensen-Hjell, 1885. Oil on canvas, 190 x 100 cm. Private Collection.

It was particularly through representations of the body, sexuality, and nature that many Expressionists enacted both their resistance to bourgeois culture and their accompanying search for rejuvenated creativity. In this context, the naked frolics of the Brücke artists and models on their summer excursions to the Moritzburg lakes, north of Dresden, are not the lunatic forays of decadent bohemians, but are also related to existing contemporary trends.

They went there in the summers of 1909, 1910 and 1911. Max Pechstein gave an idyllic description, recalling the spirit of their trip in 1910, when he, Kirchner and Heckel were accompanied by friends and models: “We lived in absolute harmony; we worked and we swam. If a male model was needed … one of us would jump into the breach.” The communal harmony was entirely in keeping with the utopian spirit of Gemeinschaft, or “community”.

On the 1910 trip to Moritzburg, Kirchner painted his Nudes Playing Under a Tree. This and other works, such as a woodcut showing a group of nudes playing with reeds, show evidence of Kirchner’s interest in a set of carved and painted wooden beams that he had recently sketched in the Dresden Ethnographic Museum. These carvings, from a men’s club in the Micronesian Palau Islands, depicted scenes of daily life and erotic mythology, such as a story of a native with a giant penis who was capable of penetrating his wife on another island.

Pechstein was so enamoured with his fantasy of life in the South Seas that, like Gauguin before him, he actually travelled to the Palau Islands in 1914. Kirchner’s “primitivism” too is not purely stylistic; it also involves an eroticism that is deliberately unsophisticated, “instinctive” and implicitly primeval. This would have been at odds with even the more liberated of the conservative nature-worshippers. The “primitivism” aspired to by the Wandervögel and free body cultists was essentially either pan-German medievalism or “healthy” asexual aestheticism, not liberated sexuality.

The embracing couple in Kirchner’s painting alone goes against the terms of conservative German naturism, which had a strong emphasis on health and often prescribed gender-segregated areas for its patrons. Thus, while the Brücke joined their fellow Germans in their escapes to the country, their physical and aesthetic response to nature had very little to do with intellectualised therapy or sentimental nationalism.

Back in the city, the Brücke studios in Dresden were communal, social environments for creativity and liberated nudity. A later photograph of a friend, Hugo Biallowons, dancing naked across Kirchner’s Berlin studio, although taken after the Brücke had disbanded, conveys something of this ambience. These were other “alternative” spaces, outside the norms of public life. The Brücke’s work, lifestyle and interiors are all redolent of a reaction against “civilised” sophistication and “civilised” sexual etiquette. The rough-hewn wood sculptures and woodcuts they made were part of the search for a “direct” way of working. It is also no coincidence that Kirchner painted his human subjects with pseudo-African carvings, exotic accessories or against backdrops of the murals and wall-hangings with “primitive” motifs of lovers that decorated their Dresden studios.

Late in 1909, Kirchner and Heckel began using two young girls, Fränzi and Marzella, aged somewhere between ten and fifteen, as models for numerous paintings and graphic works. They came from the local working-class district of Friedrichstadt. In the Brücke works, they sometimes appear in outdoor settings – they accompanied the artists to the lakes in 1910 – but usually they are in the studio, often nude and shown with dolls, animals or “primitive” carvings.

Adolescent subjects had provided powerful and controversial material in Germany already. Frank Wedekind’s play, Frühlingserwachen (Spring’s Awakening), written in 1890-1891, focused on the tragic fate of three adolescents for whom the onset of puberty awakens feelings and emotions that throw them into direct conflict with the structures of bourgeois morality. Breaking several taboos at once (homosexuality, suicide and abortion among them), it was banned in Germany for several years. But by the time the Brücke