10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Emil Nolde, E.L. Kirchner, Paul Klee, Franz Marc as well as the Austrians Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele were among the generation of highly individual artists who contributed to the vivid and often controversial new movement in early twentieth-century Germany and Austria: Expressionism. This publication introduces these artists and their work. The author, art historian Ashley Bassie, explains how Expressionist art led the way to a new, intense, evocative treatment of psychological, emotional and social themes in the early twentieth century. The book examines the developments of Expressionism and its key works, highlighting the often intensely subjective imagery and the aspirations and conflicts from which it emerged while focusing precisely on the artists of the movement.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 239

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Author: Ashley Bassie

© 2023, Parkstone Press International, New York

© 2023, Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Max Beckmann Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Otto Dix Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Hugo Erfurt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Conrad Felixmüller Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Art © George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

© Alfred Hanf

© Erich Heckel Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Alexeï von Jawlensky Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Wassily Kandinsky Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

© By Ingeborg & Dr. Wolfgang Henze-Ketterer, Wichtrach/Bern

© Paul Klee Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Oskar Kokoschka Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Pro Litteris, Zurich

© Käthe Kollwitz Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Ludwig Meidner

© Kunstsammlungen Böttcherstraße Bremen, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum

© Otto Mueller Estate / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Edvard Munch Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ Bono, Oslo

© Gabriele Münter Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Heinrich Nauen Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Emil Nolde Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

© Max Pechstein Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Christian Rohlfs Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Karl Schmidt-Rottluff Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Foto : Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus München

© Sprengel Museum Hannover, Photo: Michael Herling/Aline Gwose

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-326-3

Ashley Bassie

Contents

WHAT IS EXPRESSIONISM?

“GERMAN” ART?

Expressionism’s Origins and Sources

THE BODY AND NATURE

THE SELF AND THE PSYCHE

THE METROPOLIS AND MODERNITY

VISION AND THE SPIRIT

WAR AND REVOLUTION

THE END OF EXPRESSIONISM?

MAJOR ARTISTS

MAX BECKMANN (1884 Leipzig – 1950 New York)

OTTO DIX (1891 Untermhaus bei Gera – 1969 Singen)

GEORGE GROSZ (1893 Berlin – 1959 Berlin)

WASSILY KANDINSKY (1866 Moscow – 1944 Neuilly-sur-Seine)

E.L. KIRCHNER (1880 Aschaffenburg – 1938 Frauenkirch)

PAUL KLEE (1879 nr. Berne – 1940 Muralto)

OSKAR KOKOSCHKA (1886 Pöchlarn an der Donau – 1980 Montreux)

FRANZ MARC (1880 Munich – 1916 Verdun)

EMIL NOLDE (1867 Nolde-1956 Seebüll)

EGON SCHIELE (1890 Tulln – 1918 Vienna)

Bibliography

Index

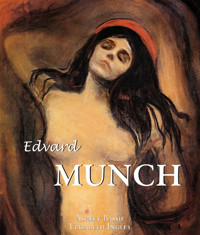

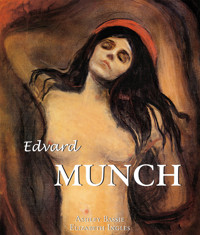

Edvard Munch,Madonna, 1893-1894.

Oil on canvas, 90 x 68.5 cm.

Munch-museet, Oslo.

WHAT IS EXPRESSIONISM?

Expressionism has meant different things at different times. In the sense we use the term today, certainly when we speak of “German Expressionism”, it refers to a broad, cultural movement that emerged from Germany and Austria in the early twentieth century. Yet Expressionism is complex and contradictory. It encompassed the liberation of the body as much as the excavation of the psyche. Within its motley ranks could be found political apathy, even chauvinism, as well as revolutionary commitment. The first part of this book is structured thematically, rather than chronologically, in order to draw out some of the more common characteristics and preoccupations of the movement. The second part consists of short essays on a selection of individual Expressionists, highlighting the distinctive aspects of each artist’s work.

Expressionism’s tangled roots range far back into history and across wide geographical terrain. Two of its most important sources are neither modern, nor European: the art of the Middle Ages and the art of tribal or so-called “primitive” peoples. A third has little to do with visual art at all – the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. To complicate matters further, the word “Expressionism” initially meant something different. Until about 1912, the term was used generally to describe progressive art in Europe, chiefly France, that was clearly different from Impressionism, or that even appeared to be “anti-Impressionist”. So, ironically, it was first applied most often to non-German artists such as Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse and Van Gogh. In practice, well up to the outbreak of the First World War, “Expressionism” was still a catch-all phrase for the latest modern, Fauviste, Futurist or Cubist art. The important Sonderbund exhibition staged in Cologne in 1912, for example, used the term to refer to the newest German painting together with international artists.

In Cologne though, the shift was already beginning. The exhibition organisers and most critics emphasised the affinity of the “Expressionism” of the German avant-garde with that of the Dutch Van Gogh and the guest of honour at the show, the Norwegian Edvard Munch. In so doing, they slightly played down the prior significance of French artists, such as Matisse, and steered the concept of Expressionism in a distinctly “Northern” direction. Munch himself was stunned when he saw the show. “There is a collection here of all the wildest paintings in Europe”, he wrote to a friend, “Cologne Cathedral is shaking to its very foundations”. More than geography though, this shift highlighted Expressionist qualities as lying not so much in innovative formal means for description of the physical world, but in the communication of a particularly sensitive, even slightly neurotic, perception of the world, which went beyond mere appearances. As in the work of Van Gogh and Munch, individual, subjective human experience was its focus. As it gathered momentum, one thing became abundantly clear – Expressionism was not a “style”. This helps to explain why curators, critics, dealers, and the artists themselves, could rarely agree on the use or meaning of the term.

Oskar Kokoschka,Dents du Midi, 1909-1910.

Oil on canvas, 80 x 116 cm.

Private collection.

Nonetheless, “Expressionism” gained wide currency across the arts in Germany and Austria. It was first applied to painting, sculpture and printmaking and a little later to literature, theatre and dance. It has been argued that while Expressionism’s impact on the visual arts was most successful, its impact on music was the most radical, involving elements such as dissonance and atonality in the works of composers (especially in Vienna) from Gustav Mahler to Alban Berg and Arnold Schoenberg. Finally, Expressionism infiltrated architecture, and its effects could even be discerned in the newest modern distraction – film.

Historians still disagree today on what Expressionism is. Many artists who now rank as quintessential Expressionists themselves rejected the label. Given the spirit of anti-academicism and fierce individualism that characterised so much of Expressionism, this is hardly surprising. In his autobiography, Jahre der Kämpfe (Years of Struggle), Emil Nolde wrote: “The intellectual art literati call me an Expressionist. I don’t like this restriction”.

Egon Schiele,Autumn Sun I (Rising Sun), 1912.

Oil on canvas, 80.2 x 80.5 cm.

Private Collection.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner,Street, Dresden, 1907-1908.

Oil on canvas, 150.5 x 200.4 cm.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Vast differences separate the work of some of the foremost figures. The term is so elastic it can accommodate artists as diverse as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Egon Schiele and Wassily Kandinsky. Many German artists who lived long lives, such as Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Otto Dix and Oskar Kokoschka, only worked in an “Expressionist” mode – and to differing degrees – for a small number of their productive years. Others had tragically short careers, leaving us only to imagine how their work might have developed. Paula Modersohn-Becker and Richard Gerstl died before the term had even come into common use. Before 1914 was out, the painter August Macke and the poets Alfred Lichtenstein and Ernst Stadler had been killed on the battlefields. Another poet, Georg Trakl, took a cocaine overdose after breaking down under the trauma of service in a medical unit in Poland. Franz Marc fell in 1916. In Vienna the young Egon Schiele did not survive the devastating influenza epidemic of 1918, and Wilhelm Lehmbruck was left so traumatised by the experience of war that he took his own life in Berlin in 1919.

It is easier to establish what Expressionism was not, than what it was. Certainly Expressionism was not a coherent, singular entity. Unlike Marinetti’s Futurists in Italy, who invented and loudly proclaimed their own group identity, there was no such thing as a unified band of “Expressionists” on the march. Yet unlike the small groups of painters dubbed “Fauves” and “Cubists” in France, “Expressionists” of one hue or another, across the arts, were so numerous that the epoch in German cultural history has sometimes been characterised as one of an entire “Expressionist generation”.

Edvard Munch,Evening on Karl Johan Street, 1892.

Oil on canvas, 85.5 x 121 cm.

Bergen Art Museum,

Rasmus Meyers Collection, Bergen.

The era of German Expressionism was finally extinguished by the Nazi dictatorship in 1933. But its most incandescent phase of 1910-1920 left a legacy that has caused reverberations ever since. It was a period of intellectual adventure, passionate idealism, and deep yearnings for spiritual renewal. Increasingly, as some artists recognised the political danger of Expressionism’s characteristic inwardness, they became more committed to exploring its potential for political engagement or wider social reform. But utopian aspirations and the high stakes involved in ascribing a redemptive function to art, meant that Expressionism also bore an immense potential for despair, disillusionment and atrophy. Along with works of profound poignancy, it also produced a flood of pseudo-ecstatic outpourings and a good deal of sentimental navel-gazing. This book will give a wide berth to some of the murkier by-products of a genuinely radical project.

Some of the most stunning products of German Expressionism came from formal public collaborations as well as intimate working friendships. There were elements of both in the groups most important for pre-war Expressionism, the Brücke (Bridge) and Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider), for instance. Fierce arguments were conducted and common ground was staked out in journals such as Der Sturm (The Storm) and Die Aktion (Action), as well as in the context of numerous group exhibitions. Others came from introspective loners working in relative isolation. Crucially, this was also an age shattered by the crisis of a devastating technological war and in Germany, its most debilitating aftermath. The conflict and trauma of the period is inseparable from the forms Expressionism took, and ultimately, from its demise.

Edvard Munch,Self-Portrait with Cigarette, 1895.

Oil on canvas, 110.5 x 85.5 cm.

Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst, arkitektur og, design, Oslo.

“GERMAN” ART?

Expressionism’s Origins and Sources

This chapter explores the rich mixture of ideas, debates, influences and sources that contributed to the way Expressionism developed in Germany. It also introduces the two key groups of pre-war Expressionism; Die Brücke in Dresden and Der Blaue Reiter in Munich.

Art in late nineteenth-century Wilhelmine Germany was dominated by professional institutions, such as the Academy, and by artistic conventions, such as the emphasis on historical and literary subjects as those most worthy for public exhibition. The mixture of intricate realism, patriotism and cosy sentimentality in Anton von Werner’s Im Etappenquartier vor Paris (In a Billet outside Paris) exemplifies well “official” taste in the 1890s. As soon as it had been completed, it was bought for the Nationalgalerie. The painting shows a comradely group of soldiers relaxing to the strains of a Lied by Schumann, Das Meer erglänzte weit hinaus, played and sung by two lancers. The setting is a requisitioned chateau just outside Versailles during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Their bluff manliness – all muddy boots and ruddy cheeks – and wholesome love of German Kultur is very deliberately contrasted with the effete rococo fussiness of French Zivilisation in their surroundings. Von Werner was director of the Berlin Academy and the most powerful figure in the institutional German art world at the time. He was also the favourite of Kaiser Wilhelm II, himself notoriously opinionated, conservative and outspoken in his views on art.

All the more shocking, then, was the work sprung on an unsuspecting public at the newly-opened headquarters of the conservative Verein Berliner Künstler (Union of Berlin Artists) in 1892. It was by a Norwegian artist then still unknown in Germany, but who would inspire many Expressionists in the decades to follow – Edvard Munch. He had been invited to exhibit and arrived with fifty-five works, including one or more versions of The Kiss. This image re-surfaced many times in Munch’s oeuvre. For him, it was tied up with the idea of the destructiveness of passion. He meant this not in terms of its potential for social disgrace, but more profoundly: a woman’s passion had the power to enslave men, arouse jealousy and – here almost literally – eat into the strength of the individual. When Erich Heckel met Munch in 1907, Munch offered the young German artist his Strindbergian view of women: “Das Weib ist wie Feuer, wärmend und verzehrend”. (“Woman is like fire, warming and consuming”.) If we try to imagine the effect images like Munch’s had on the conservative “establishment”, we can also understand something of the sexual insecurities of the age. Critics scorned Munch’s pallid colours, likening them to a housepainter’s undercoat. But more than considerations of technique, it was the subjects of Munch’s work that offended conservative sensibilities. The writer, friend and biographer of Munch, Stanislaw Przybyszewski, articulated the most unsettling aspect of The Kiss when he noted of the figures that:

“We see two human figures, each of the two faces melting into the other. Not a single recognisable facial feature remains: all we see is that point where they melt, a point that looks like a huge ear, rendered deaf by the ecstasy of the blood. It looks like a pool of molten flesh: there’s something hideous in it”.

To the cultured men of the Verein, with their taste for heroic battle scenes and history painting, The Kiss, along with Munch’s other deeply introspective syntheses of the taboos of sex, death and intense emotion, were anathema. Add to this the howls of protest from the press and it is no surprise that the exhibition was closed after just one week. Paradoxically, the scandal did more for Munch’s career than any other event. In fact, it made his name in Berlin almost overnight. Munch wrote a letter home from Berlin to Norway:

“I could hardly have received better advertising … People came long distances to see the exhibition … I’ve never had such enjoyable days. It’s incredible that anything as innocent as art can create such furore. You asked me whether it has made me nervous. I’ve gained six pounds and have never felt better”.

The incident had far-reaching ramifications. It caused a rift between liberal and conservative members of the Verein that ultimately led to the foundation of the more progressive Berlin Secession. A decade later, Munch was to become a rich source of inspiration for Expressionist artists as they explored ways of giving form to subjective perception and emotional states, rather than mimesis and anecdote.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, two of Germany’s most distinctive and original artists were women: Paula Modersohn-Becker and Käthe Kollwitz. Kollwitz had a long, prolific career that lasted from the 1890s until her death – just days before the end of the Second World War – well after Expressionism’s demise. Like Munch, her work often deals with profound emotion, birth, suffering and death. But it is otherwise very different. His work emerged from a Symbolist, bohemian milieu, pungent with sex and decadence on the one hand, and a highly personal, subjective sensitivity to the natural sublime on the other. Hers came from a Realist tradition of humane socio-political engagement and fundamental philanthropy. Kollwitz was primarily a graphic artist, making works on paper ranging from brief, gestural drawings to numerous versions of intricate etchings, finely tuned to the effects of subtle tonal variations.

Unlike Kollwitz, Paula Modersohn-Becker died young, before “Expressionism” even came into common parlance. Groups like the Brücke in their early phases knew little or nothing of her work. Emil Nolde met her in Paris in 1900, but this was before she had developed the style on which her posthumous reputation came to rest. Nonetheless, she is an interesting precursor of Expressionism.

As a woman artist, Modersohn-Becker was not admitted to the traditional Academy. She trained instead at a single-sex school in Berlin and then at the Colarossi Academy in Paris. Her work was greatly stimulated by her first-hand experience of art in the French capital, above all by Cézanne, Gauguin, Rodin and collections of Japanese art. However, her most powerful subject-matter was drawn from the German provincial countryside. She joined the established artists’ colony at Worpswede, a small village in the marshy, moorland landscape near Bremen in the north of Germany in 1898. In so doing, she was taking part in a growing tradition of creative retreats into the countryside. Other established artists’ colonies included Pont-Aven in France and St Ives in Britain. “Going away” appealed to artists in search of uncorrupted nature, colourful indigenous traditions and close-knit community.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, 1897.

Oil on canvas, 99 x 80.5 cm.

Munch-museet, Oslo.

Paula Modersohn-Becker,Trumpeting Girl, 1903. Oil on canvas.

Kunstsammlungen Böttcherstraße,

Paula Modersohn–Becker Museum, Bremen.

Paula Modersohn-Becker,Old Woman in Garden, 1907. Oil on canvas.

Kunstsammlungen Böttcherstraße,

Paula Modersohn–Becker Museum, Bremen.

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, After the Bath, 1912.

Oil on canvas, 84 x 95 cm.

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden,

Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden.

In short, what many were seeking was life untouched by the ruptures of capitalist modernity. In fact, such artists’ colonies were themselves products of the railway age, the tastes of urban art markets and modern, exoticising fantasies about the folk cultures of distant provinces. In the case of Modersohn-Becker, the landscape, local inhabitants and fellow artists at the Worpswede colony provided her with conditions in which she was able to develop a highly personal style. Her monumental portrait of an old woman from the local poorhouse is remarkable for the strong sense of design, semi-abstract forms, and the finely tuned evocation of the shadows and fading glow of the Northern twilight. Even more striking is the sense of powerful, dignified human presence with which she has endowed the old woman.

Modersohn-Becker was often ambivalent about the Worpswede life and felt a lack of stimulation there. She married another Worpswede artist, Otto Modersohn, but her antidote to the colony’s insularity was Paris (which she called the “world”). She was a sophisticated artist, but in her drive for directness and truthfulness, she avoided sentimentalising or romanticising her subjects. This is part of what distinguishes her work from that of artists who went into the countryside looking for subjects to match their own or their collectors’ received ideas of the countryside. She died in 1907, aged thirty-one, a few weeks after giving birth to a daughter.

Another member of the Worpswede colony and a close friend, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, dedicated a requiem, full of images of life and fertility, to her:

For you that understood: the heavy fruit.

You placed it there in front of you on platters

And balanced then its heaviness with colour.

And much like the fruit you also saw the woman,

And you saw children thus: intrinsically –

Driven into the forms of their existence …

The tension between cosmopolitan modernity and indigenous nature was an important political factor in debates around Germany’s artistic heritage and future. The concept of “German Art” was controversial before, during, and after the era of Expressionism. But it was an especially contested issue in Wilhelmine Germany – from unification in 1871 until the empire’s collapse in 1918.

At that time, discussion of modern art was often tied to concerns for German national identity. Julius Langbehn’s nationalist Rembrandt als Erzieher (Rembrandt as Educator), published in 1890, became an instant best-seller. Langbehn had no qualms about defining Rembrandt as German, who, along with Goethe and Luther, constituted the “culture” that would be “the true salvation of the Germans”. His book diagnosed contemporary Germany as a culture in decline, threatened on all sides by internationalism, science, democracy – in short, by modernity. The nationalist cant of anti-modernism was taken up in the following decades by, amongst others, Carl Vinnen, a conservative painter of landscapes, also from Worpswede. He published an inflammatory collection of texts, signed by 118 artists, under the title Ein Protest deutscher Künstler (A Protest of German Artists) in 1911. Vinnen had become embittered at the purchase by the museum in Bremen of an expensive landscape by Van Gogh. In spite of his Dutch roots, Van Gogh was equated with what Vinnen saw as the “great invasion of French art”. Furthermore, “French art” soon came to stand for modernism in general, including Expressionism.

Paula Modersohn-Becker,Self-Portrait with Camellia, 1906-1907.

Oil on wood, 61 x 30.5 cm.

Museum Folkwang, Essen.

An ardent defence, in the form of a published counter-statement Im Kampf um die Kunst (The Struggle for Art) was quickly mounted by the pro-modernist camp: progressive artists, writers and collectors. They included the art historian Wilhelm Worringer, members of the emerging Blaue Reiter circle and Max Beckmann. Although Expressionist art itself was often quite strikingly apolitical, this early conflict in its history highlighted the cultural-political dimension of the issue of Expressionism in the German context. This became especially clear in the 1930s when theorists on the Left debated retrospectively the successes and failures of Expressionism, and the campaign against modernism, internationalism and Expressionism re-ignited with greater violence in the form of the National Socialists’ campaign against so-called Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art).

What became Expressionism, in the sense it has now, first began to emerge just a few years into the new century. In Dresden, a group of young architecture students at the city’s Technical University began meeting to read, discuss and work together in Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s student lodgings. Dissatisfied with conventional academic art training, they organised informal life-drawing sessions using a young model, with short poses that they were only able to capture in quick, decisive, “courageous” lines, as one of them, Fritz Bleyl, put it. This way of working liberated them from the academic practices of drawing meticulously from a model in stiff, eternal poses, working from dirty old plaster casts, or copying slavishly from the Old Masters. By 1905, they decided to formalise their independent group, chiefly for exhibition purposes. They drew, painted and made prints, first in an improvised studio space organised by Erich Heckel – it was an attic in his parents’ house in the Friedrichstadt district – and later in a series of other studios in the neighbourhood.

An important early statement of intent came in 1906. In the catalogue to their first group exhibition, held in Löbtau, Dresden, they issued their rallying cry. This was in the form of a founding “manifesto” of the Künstlergruppe Brücke (Bridge Artists’ Group). Printed in stylised, quasi-primitive lettering, the text reads:

WITH FAITH IN DEVELOPMENT AND IN A NEW GENERATION OF CREATORS AND APPRECIATORS, WE CALL TOGETHER ALL YOUTH. AS YOUTH, WE CARRY THE FUTURE AND WANT TO CREATE FOR OURSELVES FREEDOM OF LIFE AND OF MOVEMENT AGAINST THE LONG-ESTABLISHED OLDER FORCES. EVERYONE WHO WITH IMMEDIACY AND AUTHENTICITY CONVEYS THAT WHICH DRIVES HIM TO CREATE, BELONGS WITH US.

The “drive” to create came from the core members of the Brücke group: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl. Bleyl left the group in 1907 to pursue a career in architectural design. Max Pechstein and the Swiss artist Cuno Amiet joined in 1906. Upon invitation, Emil Nolde, an older artist, became a member for a short while (1906-1907) and later they were joined by Otto Mueller.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner,Dodo and Her Brother, 1908-1920.

Oil on canvas, 170.5 x 95 cm.

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton.

Wassily Kandinsky, Sketch for the cover of the Blaue Reiter almanach, 1911.

Watercolour, 28 x 20.5 cm.

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

The woodcut medium was central to the Brücke from an early stage. In painting, although there were differences between individual artists’ work, the early canvases are often characterised by intense, non-naturalistic colouring and loose, broken brushwork. They reveal a lively engagement with recent art in Europe. Kirchner, Heckel and others absorbed and worked through the implications of modern international art; of French postimpressionism – Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat and Van Gogh – and, a little later, of Matisse and Munch. These artists’ work could be seen in numerous exhibitions across Germany at the time. It was widely documented and debated in the art press and in influential books such as Julius Meier-Graefe’s monumental Entwicklungsgeschichte der modernen Kunst (History of the Development of Modern Art), published in 1904.

Jugendstil, the turn-of-the-century reform movement in the decorative arts, also made an impact on the Brücke in its infancy. The sinuous contours of the Jugendstil aesthetic appear in some early Brücke prints. More fundamental principles of the movement, such as the desire to renew the arts and break down traditional barriers between the fine and applied arts, are also echoed in some of the ideals of the emerging Expressionist movement.

Like many avant-garde artists across Europe, the Brücke discovered a new world of form, materials, imagery and symbolism in the art of non-western cultures. Their imaginative response to African and Oceanic cultures was part of the wider phenomenon of “primitivism”, often rooted in Western exoticising fantasies. But in the German Expressionist context, this was also part of a search for collective “origins”, going back to the elusive “essence” of human creativity. Many of the idealised notions of directness, instinctiveness and authenticity at the core of Expressionist ideology are related to the Brücke’s and other Expressionists’ interest in the traces of “primitive” cultures reproduced through the media of ethnography.

In an interesting variant on the Expressionist search for “authentic” origins, Mueller was drawn to the gypsy communities of Eastern Europe, travelling to Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria in the 1920s to paint and study them. He often painted his subjects using tempera on rough canvas, giving his works a “dry” and deliberately unpolished quality. Mueller seems to have felt a strong personal affinity with the gypsies he painted – his mother came from a gypsy family, but had been abandoned as a child.

Finally, Expressionism involved a unique and complex confrontation with another powerful source; that of the German artistic past. There is an intricate connection between German Expressionism and the art of the Middle Ages. In some ways, the Expressionists’ “rediscovery” of the medieval Gothic was related to the wider primitivist project – the search for what they imagined as “pure”, authentic, vital art. For many, the art of the Middle Ages possessed a powerful integrity. Its handcraft traditions and expressive, non-naturalistic forms, resonant of profound piety, were understood as the product of an intuitive tradition.

Emil Nolde, whose own politics tended towards the völkisch-nationalist, responded passionately to the art of so-called “primitive” peoples, or Urvölker, but, in keeping with Expressionism’s anti-academic stance, he was dismissive of art-historical orthodoxy. Ironically, the history of “great art” that he takes issue with was the legacy of a Prussian: the antiquarian and “father of art history”, Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768). An early draft of a book on tribal art that Nolde wanted to publish began:

“1. ‘We see the highest art in the Greeks. In painting, Raphael is the greatest of all Masters.’ This was what every art pedagogue taught twenty or thirty years ago.

“2. Some things have changed since then. We don’t like Raphael and the sculptures of the so-called flowering of Greek art leave us cold. Our predecessors’ ideals are no longer ours. We like less the works under which great names have stood for centuries. Sophisticated artists in the hustle and bustle of their times made art for Popes and palaces. We value and love the unassuming people who worked in their workshops, of whom we barely know anything today, for their simple and largely-hewn sculptures in the cathedrals of Naumburg, Magdeburg, Bamberg”.