9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

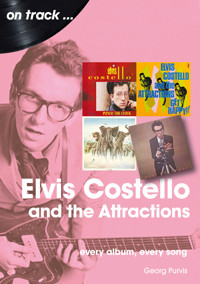

- Herausgeber: Sonicbond Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: On Track

- Sprache: Englisch

Whether you know him as Howard Coward, Napoleon Dynamite, or the Emotional Toothpaste, and are familiar with his work with The Attractions, The Confederates, or The Imposters, Elvis Costello’s career has always been about reinvention and his vast catalogue of over 30 studio albums since 1977 is a testament to his prolificacy.

However, this book focuses on his most acclaimed and accessible work, recorded mostly with The Attractions (Steve Nieve, Pete Thomas, and Bruce Thomas) between 1977 and 1986, although some other high-profile friends – Nick Lowe, Billy Sherrill, and T-Bone Burnett, among others – show up along the way. From his modest solo beginnings as a pub rocker with attitude on My Aim Is True to his cacophonous epitaph to The Attractions on Blood & Chocolate, this book follows a hectic and, at times, baffling career trajectory that often ignored commercial fame and fortune in favour of artistic freedom and expression.

Elvis Costello and The Attractions – On Track explores every album, every song, and every non-album B-side or contemporary cast-off from the band’s all-too-brief whirlwind decade of existence.

Georg Purvis is the author of Queen: The Complete Works and Pink Floyd In the 1970s. His first Elvis Costello albums were This Year’s Model and When I Was Cruel, both purchased at the same time in 2002. He has seen Elvis live about a dozen times since 2007 and is always thrilled to report that each concert had been spectacularly different from the previous one. He lives in Philadelphia with his wife, Meredith, and their two cats, Spencer and William.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 314

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Elvis Costello and the Attractions

Every Album, Every Song

On Track

Georg Purvis

For my Family.

Dedicated to David Moreau, who accompanied me to my first Elvis Costello concert at the Electric Factory in Philadelphia on 19 May 2007.

Contents

Without Whom …

Foreword

1. Introduction: Oh, I Just Don’t Know Where To Begin…

2. My Aim Is True (1977)

3. This Year’s Model (1978)

4. Armed Forces (1979)

5. Get Happy!! (1980)

6. Trust (1981)

7. Almost Blue (1981)

8. Imperial Bedroom (1982)

9. Punch the Clock (1983)

10. Goodbye Cruel World (1984)

11. King of America (1986)

12. Blood & Chocolate (1986)

Postscript: This Is Only the Beginning

13. Compilations, Live Albums, and The Attractions’ Solo’ Album

14. Resources and Further Reading

Without Whom …

This book is the culmination of nearly 20 years of appreciation, admiration, and (occasional) devotion for Elvis Costello. Thanks to Stephen Lambe for the opportunity to write this book, and for his immense passion and appreciation for good music.

Thanks to my friends and family who helped and supported me along the way: Scott Armstrong, Bob Bingaman, Noel Bartocci and Sam Costa, Raoul Caes and Jess Roth, Mark Costello, Mike Czawlytko and Julia Favorov, Jacob Carpenter, Tom Castagna, Joe and Danielle DeCarolis, Nick, Nikki and Mia DiBuono, Marissa Edelman, Rachael Edwards, Eileen Falchetta, Matt Gorzalski, Julia Green and Phil DeBiasio, Dave Grow and Michelle Scott, Betty and Chris Hackney, Jim, Louise, Penelope and Jordan Kent, Scott Koenig, JD Korejko and Su-Shan Jessica Lai, Kristen Kurtis, Steph Larson, Dan Lawler, John Malhman IV and Alessa Abruzzo, Brad McGinnis, Olivia Miller, Nick Prestileo, Billy and Annie Ransford, Patrick Remington and Beth Johnston, Heather Sailer, Kyra Schwartz and Syd Steinberg, Steve Sokolow, Eleni Solomos, John Dougherty and Valentina, Christine, Lillian and Everett Swing, Erin Tennity and Randy Richard, and Eric Zerbe. Additional thanks to Philip Brooks for advice, helping me through some tough times, and asking me if the book’s done yet!

Special thanks to:

Lori, Hugh and Edward McGovern; my father, Georg; Patrice Babineau; my mother, Lynn; and my sister, Leah. Steph Mlot, for being an eager pupil to an overzealous teacher (at least that’s how I viewed it!) – and for the Sugarcanes’ concert in Wolf Trap; Cameron Cuming, for being a willing sport and overall good egg (despite your insistence that Goodbye Cruel World is better than it actually is); Chelsea Bennett, for sharing the obsession, our many discussions on each successive EC album release and what we liked or didn’t like, and humouring my drunken rendition of ‘Beyond Belief’ at your request; and Meredith McGovern, for your eternal love and support and for being a willing participant in this hobby of mine. I love you, my funny valentine.

Foreword

I first became aware of Elvis Costello in 1999, when three of my friends and I saw Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, for my 16th birthday. I won’t pretend I didn’t find the movie hilarious, but I was going through something of a musical revelation at the time and was wildly impressed with the soundtrack: The Who, Lenny Kravitz – Green Day appealed to my teenage male sensibilities, while I harboured a secret appreciation of Madonna’s ‘Beautiful Stranger’. But it was the bizarre cameo appearance of Elvis Costello and Burt Bacharach in swingin’ London circa 1969 that grabbed me. I had been peripherally aware of Costello, so much that I knew this collaboration with Bacharach was an anomaly, but nothing had compelled me to explore his music any further.

Sometime in April 2002, while walking around a Borders book store, I came across two CDs that captured my attention. The first appeared to be two large plastic cartoon bees, perhaps a child’s toy at a carnival; the second was an intense-looking geek scowling at me over a Hasselblad camera. I bit the bullet and bought both. In my car, I put This Year’s Model into the CD player first and was disappointed that I didn’t immediately love it, having heard so much about it. I gave When I Was Cruel a chance instead, and that did it: I needed to get everything by this man. And so I did – but I wasn’t much of a concert-goer at the time, and so it took me five years before I finally witnessed Elvis and his new backing band The Imposters (two-thirds of The Attractions with bassist Davey Faragher) live. From that moment forward I vowed to see him whenever I could, and I’m glad I did, because each successive concert has been a wildly different experience – and sometimes backing band – each time. If you’re reading this and you haven’t seen Elvis live yet, you absolutely must.

I’d wanted to write an Elvis Costello book for years, but I couldn’t find the right angle. He’s already written the definitive autobiography – twice: the first was between 1993 and 2005, as Rykodisc and, later, Rhino reissued his records on CD and included extensive self-penned liner notes that got as close to an autobiography that fans would get, until he published his autobiography – Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink – in 2015.

So I chose to whittle my focus down to Elvis Costello and his time with The Attractions, though two solo albums – My Aim Is True (1977) and King of America (1986) – are integral parts of the story and so are discussed. Additionally, I’ve opted not to discuss in depth The Attractions’ brief reunion in the 1990s or the two albums they then featured on Brutal Youth and All This Useless Beauty – there’s enough meat on that bone for an eventual follow-up.

One final note: Elvis was a fan of pseudonyms and nom de plumes – famously reverting to his birth name in 1985 – the instances of which are noted throughout the text when appropriate. For the sake of your sanity and mine, I address him as Declan in the introduction and first half of the first chapter to the point he became known professionally as Elvis Costello. From there, regardless of how he was credited, I refer to him by his professional name, except in the event of a quote, song credit, or personnel credit.

Introduction: Oh, I Just Don’t Know Where To Begin…

Declan Patrick MacManus was born on 25 August 1954 to Ross and Lillian MacManus. His first record was The Beatles’ Please Please Me, purchased by Ross for the nine-year-old. The following year, Declan used his own money to acquire Georgie Fame’s Fame at Last EP.

This wasn’t young Declan’s first taste of music: his father was a trumpeter, vocalist, and bandleader; his mother, a record store manager. Throughout much of Declan’s childhood, his father was the featured vocalist for the Joe Loss Orchestra (Britain’s top big band), and a solo artist, scoring a minor hit with ‘Patsy Girl’ in Germany in 1966. Four years later, Ross – now going by Day Costello – achieved another hit single, this time in Australia, with The Beatles’ ‘The Long And Winding Road’.

Given his upbringing, Declan’s fate as a musician was a given. His first commercially available performance was on Ross’s jingle for R. White’s Lemonade, where Declan sang backing vocals and played guitar. By this point, he had formed the acoustic duo, Rusty, with his school friend, Allan Mayes, thus being exposed to the thrill of an enraptured audience, as well as the downsides of the music industry: the two might earn up to £10 a night, but it was more common that they would walk away with nothing.

By the end of 1972, Declan was living in with his mother in Liverpool and – despite recording a six-track demo with Mayes – decided that the music scene was too limited and upped sticks to London to live with his father, by now remarried. He also needed money and got a job as a computer operator at the Elizabeth Arden factory in Acton; it was menial work (‘My duties included printing out invoices for the moustache waxes of the occasional Duchess who visited the company’s West End salon. Some of the work was more tedious’), often completed quickly and without much supervision, so he spent most of his time honing his songwriting skills.

In mid-1973, Declan discovered the pub rock band Brinsley Schwarz and hit it off with two fellow fans, Mich Kent and Malcolm Dennis. The three had several common music interests (The Band, Little Feat, Gram Parsons, Grateful Dead and Joni Mitchell) and were struggling musicians – Kent a bassist, Dennis a drummer. Before long, Dickie Faulkner (congas) and Steve Hazlehurst (guitar, vocals) joined. (Dennis left in early 1975 after a punch-up with Declan; Ian Powling replaced Dennis on drums.). A name was needed, and after The Mothertruckers and The Bizzario Brothers were (rightly) rejected, Declan’s fiancé Mary Burgoyne suggested Flip City: inspired by Cheech Marin babbling away (‘Man, the chick is twisted, crazy, poop-shoobie, y’hear? Flip city!’) on the spoken word section of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Twisted’ from her Court and Spark album.

Declan took charge of the songwriting for Flip City, but it soon became apparent that his aspirations didn’t match those of his bandmates: they found Flip City to be a fun lark, but Declan was more preoccupied with making money. It’s hard to fault him: despite making a living wage at Elizabeth Arden, he and Mary, now married, were proud parents to Matthew but still found it tough to make ends meet. Instead of taking on a promotion or a better-paying job, Declan pushed ahead with his musical aspirations, though they still had to downgrade, first by taking on some roommates who were of questionable renown. The situation got so dire that they had to move in with Mary’s parents near Heathrow airport, though Declan’s commute would inspire several of his new songs.

By the end of December 1975, Flip City was no more, and Declan was ready to make a go of it on his own. Before long, he had recorded a tape full of original compositions that he was schlepping around to largely disinterested record executives, who nonetheless humoured him anyway and let him perform some of the songs in-office. After receiving little feedback from any of the prospects (and being offered a deal from Island Records, which he found so insulting that he rejected it outright), Declan read an advertisement for the newly-formed Stiff Records and its founders, Jake Riviera and Dave Robinson. Their expanding roster included The Pink Fairies, The Damned and Nick Lowe: former Brinsley Schwarz member and an early inspiration of Declan’s, so it came as a pleasant coincidence when the two happened to run into each other while he was returning from the Stiff Records offices. Though they had first met back in 1972 – when Lowe had been impressed with Declan’s musical ambitions – there hadn’t been any contact since. Four years later, the two caught up, with Declan mentioning to Lowe the tape he had just dropped off at Stiff. The two went their separate ways, but it was not to be their final meeting.

My Aim Is True (1977)

Personnel:

Elvis Costello: vocals, guitar; piano and drumstick on ‘Mystery Dance’

John McFee: guitar, pedal steel guitar

Sean Hopper: keyboards, backing vocals

Johnny Ciambotti: bass guitar, backing vocals

Mickey Shine: drums

Nick Lowe: backing vocals; bass, piano, and drumstick on ‘Mystery Dance’

Stan Shaw: organ on ‘Less Than Zero’

Recorded at Pathway Studios, London, late 1976–early 1977

Produced by Nick Lowe

UK release date: 22 July 1977

US release date: March 1978

Highest chart places: UK: 14, US: 32

Running time: 32:31

At Stiff Records, the response to Declan’s tape was promising, and he was repeatedly called in during the subsequent few weeks to meet with various personnel. He impressed the managers of the fledgeling label enough that they signed him to Stiff (as D. P. Costello: his new surname a nod to his paternal great-grandmother’s maiden name) in August 1976. At first, it was suggested that Declan only write material for other artists – primarily Dave Edmunds – but, not content with being pigeonholed as a songwriter, Declan continued to write and record demos at an alarming rate. (It was even suggested that he share an album with fellow Stiff label-mate, Wreckless Eric, though this idea was scuppered.) Finally, Riviera and Robinson were convinced that Declan should be the one to sing his own songs, and the notion of writing songs for other artists was silently put to bed.

In October 1976, Declan was introduced to the musicians who would be the backing band on his first record. Clover were a California-based band who had been coaxed over to England by Riviera. With several albums already under their belt, they proved to be the perfect musical foil for the songs that Declan was writing and helped define his early pub rock sound (though it would be completely obliterated and revamped by the formation of The Attractions the following summer). What was even more incidental was that Declan was a fan of Clover – certainly, he was drawn to their country-rock flavour, much as he was to the Grateful Dead and The Flying Burrito Brothers, among others – and had performed a handful of their songs while in Flip City. Declan and the musicians – which included John McFee on pedal steel guitar, Sean Hopper on keyboards and backing vocals, Johnny Ciambotti on bass guitar, and Mickey Shine on drums – along with producer Nick Lowe, would rehearse the songs at Headley Grange during the day, then go to Pathway Studios in Islington at night to record them. In all, the album took sixteen hours to record and five hours to mix, at a cost of less than £1,000.

‘Simplicity’ was the word of the day, and such luxuries as overdubs or elaborate arrangements were out of the question. The basic goal was to commit the songs to plastic without too much fuss or hassle. Lowe was manning the control room with Roger Bechirian engineering, and it proved to be a perfect pairing. Lowe had little technical knowledge – leaving the complicated stuff to Bechirian – preferring to capture the initial feel and raw energy of a song instead of producing it to death. This, along with the tiny confines of Pathway Studios, gave the music its distinctive gritty sound that sat neatly as a mix somewhere between pub rock and punk.

The album was finally completed in January 1977, with Declan having used up a considerable amount of sick days to record it. He couldn’t yet afford to quit his day job – and wouldn’t be able to until the summer of 1977, nearly a year after he was signed to Stiff (his signing bonus was £150, a tape recorder, and a battery-powered guitar amplifier) – but he became a kind of unofficial Stiff employee, stopping by on the way home from work to help with ad campaigns and slogans.

With the initial plan of recording a single (‘Radio Sweetheart’ backed with ‘Mystery Dance’) now pushed aside in favour of a full-length album, a drastic change was needed. The name Declan MacManus hardly threatened the newest class of musicians who had names like Rat Scabies, Captain Sensible, and Sid Vicious; D. P. Costello, the name Declan used on his demo tapes (a nod to his father and great-grandmother), was little better. His managers insisted that he change his name to something bold, drastic, guaranteed to create controversy and even incite a little bit of anger.

Elvis Presley was still very much a beloved musical icon, though, by early 1977, he was in terminal decline due to years of drug abuse. The once iconic legend was bordering on bloated self-parody, with his concerts now incoherent messes, though his irregular stream of singles still managed to perform well in the country charts. All the same, nobody had any idea how ill he was or that he would soon pass away.

Declan had adapted a confrontational approach to his own performances – a friend recalled to biographer Graeme Thomson, that ‘he was intense, utterly focused and single-minded; he didn’t suffer fools gladly’ – which Riviera and Robinson had noticed. Having already reinvented himself on his demo tapes, Declan decided to stick with Costello as his surname (insisting it was pronounced ‘COS-tello’, instead of the more familiar ‘Cos-TELL-o’; eventually, he gave in, and the latter pronunciation stuck) while Riviera insisted his new Christian name be Elvis; Clover bassist Johnny Ciambotti recalled Riviera bursting into the studio during a session and shouting, ‘Elvis! That’s it – Elvis!’, while, according to Thomson, the more accepted legend is that ‘the change of name took place during a drunken meeting in a restaurant on the Fulham Road early in 1977’. Even Costello wasn’t sure of the new name: ‘Jake and Dave would come at you like good-cop/bad-cop’, he recalled. ‘‘This’ll be great’’, Jake just said, ‘‘We’re going to call you Elvis. Ha ha ha ha!’’. And I thought it was just one of these mad things that would pass off, and of course, it didn’t. Then it became a matter of honour as to whether we could carry it off ’.

However it was decided upon, the new name was met with a mixed reaction. Charlie Gillett – the man who had played Declan’s early demos on his radio program – was furious over what he considered a betrayal. Others found it funny, while most US critics were outraged, thinking it a slight against their own beloved Elvis. ‘It wasn’t meant as an insult to (him)’, Costello explained in late 1977. ‘It’s unfortunate if anyone thinks we’re having a go at him in any way.’ Those who were quick to clutch their pearls were obviously unaware of the timeline of events: Costello’s first single, ‘Less Than Zero’, was issued in March 1977, five months before Presley would be dead in the middle of August.

With the new name change came a change of image as well: Costello was given a pair of comically oversized horn-rimmed spectacles and dressed in the finest thrift shop threads. It was an iconic image that has been preserved on the cover of his debut album My Aim Is True (titled after a key line in the torch song of the record, ‘Alison’): clutching his Fender Jazzmaster as if he were brandishing a shotgun, Costello smirks at the camera, knock-kneed and flat- footed. It wasn’t meant to be menacing, but there was something uneasy about the photo. One critic famously said about Costello; ‘This fellow looked like he’d find it hard to aim a paper airplane’.

Stiff went into Costello overdrive, with one of their marketing ploys to get him some much-needed attention: the ‘Help Us Hype Elvis’ campaign began with the single release of ‘(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes’, with the slogan etched into the A-side’s runoff groove. Stiff ’s in-house artist, Barney Bubbles, then constructed a form for the first 1,000 copies of My Aim Is True to be released in the UK, where the purchaser of the album could fill out the form, send it into Stiff Records, and a free copy would be sent to a friend. Whether it was a success has not been confirmed, though the album’s eventual success meant that some of the promotion must have worked. Besides, who doesn’t like to be threatened into liking new musicians?

The album’s release was delayed until July 1977 due to distribution disputes between Stiff and Island Records. The momentum was lost on the record- buying public, and the album’s first three singles – ‘Less Than Zero’, ‘Alison’, and ‘(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes’ – all, well, stiffed in the UK charts. The album itself performed rather well eventually, reaching number 14 in the UK (not bad for a debut), but now Elvis was ready to promote it. He just needed a band – again.

‘Welcome To The Working Week’ (Elvis Costello)

B-side of ‘Alison’, 27 May 1977.

It’s fitting that the first song on Elvis’s first album was titled ‘Welcome To The Working Week’. Written – along with most of My Aim Is True – while commuting to his day job at Elizabeth Arden, the song takes aim at the next year’s model (‘Now that your picture’s in the paper bein’ rhythmically admired’) and the shallowness of the fashion world. In a contemporary interview, he sneered, ‘There’s nothin’ glamorous or romantic about the world at the moment’, and he would view that world through the eyes of a sexually frustrated suburban working drone who doesn’t view her modelling profession as a career, but instead as a means for self-gratification.

‘Miracle Man’ (Elvis Costello)

This song found its origins in ‘Baseball Heroes’: a track Elvis wrote and recorded with Flip City in 1974, though he later admitted that writing about the primarily American pastime was out of his league and continued to tweak the words, ending up with the song’s final title by the time Flip City disbanded. Still believing the song had promise, Elvis discarded most of the original lyric – apart from the newly-written chorus: ‘You know that walking on water won’t make you a miracle man’ – and cooked up the story of a male narrator in an unhappy relationship with a verbally abusive and dismissive woman. Not only is the song about a man who’s ‘doing everything just trying to please her/Even crawling around on all fours’, but it also portrays him as sexually impotent, which the woman doesn’t shy away from reminding him about: ‘Why do you have to say that there’s someone who can do it better than I can?’.

‘No Dancing’ (Elvis Costello)

Continuing the previous song’s subject of an impotent man in a relationship with a domineering woman, ‘No Dancing’ is written from the viewpoint of a casual observer. At first, the narrator sympathises with the man – who has been made to look like a fool by his woman – but rescinds his support in the second verse upon revealing the man’s mundane life (‘He’s such a drag/He’s not insane/It’s just that everybody has to feel his pain’), almost like that of a sex- deprived Walter Mitty.

‘Blame It On Cain’ (Elvis Costello)

Live recording B-side of ‘Watching The Detectives’, 14 October 1977.

In the Bible, Cain – the first-born son of Adam and Eve – is a land cultivator, and his younger brother, Abel, is a shepherd. Angered by God’s admiration of Abel while receiving no divine acknowledgements of his own, Cain takes his brother out to a field and mercilessly slaughters him, thus becoming history’s first murderer. ‘Blame It On Cain’ has nothing to do with that; instead, Elvis’ narrator is besieged by financial woes, and he’s willing to do whatever it takes to keep himself and his partner afloat.

Another perfunctory pub rocker, ‘Blame It On Cain’ earned its wings in the live setting, though a fairly tentative version from 7 August 1977 was released on the double B-side of ‘Watching The Detectives’. (‘Mystery Dance’, from the same concert, was the other B-side.)

‘Alison’ (Elvis Costello)

A-side, 27 May 1977.

Unlike the rest of My Aim Is True, ‘Alison’ was written not on his way to work, but at home after his wife and young son had drifted off to sleep (‘I didn’t really know what they sounded like until I got into the studio’, he later wrote). As for who Alison was?: ‘I’ve always told people that I wrote the song after seeing a beautiful checkout girl at the local supermarket’, he wrote in his autobiography, Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink:

She had a face for which a ship might have once been named. Scoundrels might once have fought mist-swathed duels to defend her honour. Now she was punching in the prices on cans of beans at a cash register and looking as if all the hopes and dreams of her youth were draining away. All that were left would soon be squandered to a ruffian who told her convenient lies and trapped her still further. I was daydreaming… Again…

Elvis goes into pretty specific detail about the song in his autobiography, and it’s worth reading uninterrupted, but the most telling assessment he made was that ‘it was a premonition, my fear that I would not be faithful or that my disbelief in happy endings would lead me to kill the love that I had longed for’. Indeed, the Live Stiffs tour shortly after the release of My Aim Is True would begin the prolonged unravelling of his personal life.

Released as the second single from the album in May 1977 – with ‘Welcome To The Working Week’ as the B-side – ‘Alison’ failed to attract any attention in the charts. (The US single mix added syrupy strings, much to Elvis’s annoyance.) It wasn’t until Linda Ronstadt covered ‘Alison’ on her 1978 album Living In the USA that the song’s status finally started to rise; while Elvis was especially dismissive of her recording, he admitted in 1998 that ‘I didn’t mind spending the money that she earned me’. Funnily enough, Ronstadt understood where Elvis was coming from: ‘If you do something and then you see someone else doing it, you think like they are taking away part of your identity. It’s a sensitive reaction; I’ve done it myself. And I took it for what it was back then. But I love Elvis. He writes like an old-fashioned songwriter. His songs are so beautifully tragic and they have a lot of meaning behind them. He’s a gentleman, and he’s got a great heart’.

‘Sneaky Feelings’ (Elvis Costello)

More pub-rock-meets-Randy-Newman, ‘Sneaky Feelings’ is one of the slighter tracks on My Aim Is True, cruising along at a jaunty pace while Elvis croons about disintegrating relationships. The song is enjoyable if unspectacular, though a quicker fade-out of the final minute – which drags on while Elvis repeats ‘Oh, I’ve still got a long way to go’ – would have been appreciated.

‘(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes’ (Elvis Costello)

A-side, 7 July 1977.

On the surface, ‘(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes’ is a simple song, one that Elvis explained as being ‘written on the Inter-City train to Liverpool between Runcorn and Lime Street stations, a journey of about 10 minutes. I had to keep the song in my head until I got to my mother’s house, where I kept an old Spanish guitar that I had had since I was a kid. The lyric is a funny notion for a 22-year-old to have written’. Indeed, the complexity of the words may be overlooked upon first listen. It’s easy to imagine the narrator as Elvis himself, a pigeon-toed, geeky and gawky young guy watching the girl – with whom he came to the dance and who left him stranded – while she flirts with more attractive men.

Musically, the song owes an obvious debt to The Byrds and Graham Parker & the Rumour, with its jangly guitar intro and surprisingly atypical vocal harmonies: notably, the sarcastic response vocals in the second chorus. The final coda is exciting, with Clover raging away as Elvis half-sneers and half- croons, ‘Red shoes, the angels wanna wear my red shoes’, as the recording fades away.

Released as the third single from My Aim Is True on 7 July 1977 – merely a week before The Attractions were formed – ‘(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes’ followed the leads of ‘Less Than Zero’ and ‘Alison’ by failing to chart. Hopes that this single would be Elvis’ breakthrough chart success were dashed, but not for long; it turned out he just needed the right band to guide him there.

‘Less Than Zero’ (Elvis Costello)

A-side, 25 March 1977.

During recording sessions for My Aim Is True, Elvis happened to watch a BBC programme which interviewed ‘the despicable Oswald Mosley ... The former leader of the British Union of Fascists seemed unrepentant about his poisonous actions of the 1930s’, Elvis later seethed. Mosley had modelled himself after Benito Mussolini and took particular offence at Jewish residents of Britain, demanding that they either renounce their heritage or be deported from the country. He attempted to organise a march through an area with a high population of Jewish residents (subsequently known as the Battle of Cable Street), but thousands of protesters of Mosley’s viewpoint prevented the march from taking place. The effect was profound enough for the country to enact the Public Order of 1936, which banned political uniforms and quasi-military-style organisations.

Elvis was so disgusted with the almost romantic reminiscing that Mosley displayed that he promptly wrote a new song that ‘was more of a slandering fantasy than a reasoned argument’. Indeed, he loaded up his descriptive shotgun and blasted Mosley’s character with a laundry list of misdeeds: sadism, brutality, paedophilia, incest, salaciousness and murder. Although Mosley hadn’t been known to participate in any of these crimes – other than adultery, which was conspicuously absent from the list – Elvis cast the leader as the embodiment of corruption. Additionally, he condemned not only Mosley’s horrendous acts but also the media for glorifying them, as evidenced in the chorus: ‘Turn up the TV, No one listening will suspect’ strongly suggests that the media is ready and willing to conceal the corruption of all politicians – implying that anyone rich and powerful enough can get away with just about anything – while desensitising viewers from the harsh glare of reality. Forty years on, and not much has changed.

Bassist Johnny Ciambotti was convinced that the ‘Mr. Oswald’ referred to Lee Harvey Oswald and the assassination of John F. Kennedy: especially the line ‘A pistol was still smoking, a man lay on the floor/Mr. Oswald said he had an understanding with the law’. One night, Ciambotti explained his interpretation to Elvis, who was so inspired by this new slant, that he wrote a completely different version. Suitably known as the ‘Dallas version’ of ‘Less Than Zero’, Elvis never got around to recording it in the studio, though it supplanted the original version in the live setting almost immediately.

‘Less Than Zero’ was released as Elvis’s first single in March 1977, and while it was an ambitious and strong composition, its blatant political overtones – coupled with its controversial list of misdeeds – made it a poor choice for the hit parade. The public certainly thought so, and the single failed to chart at all in the UK.

‘Mystery Dance’ (Elvis Costello)

B-side of ‘(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes’, 7 July 1977.

More often than not, whenever Elvis sang of dancing, on My Aim Is True, it was a not-so-subtle euphemism for fornication. So it’s no surprise that having already tackled the issue of an impotent man stuck in a loveless relationship on ‘Miracle Man’ and ‘No Dancing’, he brings everything full circle with ‘Mystery Dance’, a song that sounds like a deranged 1950s rock/doo-wop pastiche that could have been covered by Elvis the first. The story is an ode to a couple’s first sexual encounter, with each as clueless about how to begin the proceedings as the other: ‘She thought that I knew, and I thought that she knew/So both of us were willing, but we didn’t know how to do it’. Fittingly, the song is over in a brief 98 seconds, making the repeated ‘I can’t do it anymore and I’m not satisfied’ all the more appropriate.

‘Pay It Back’ (Elvis Costello)

While Elvis was mostly careful to paper over his pub rock roots on My Aim Is True, he was unable to do so on ‘Pay It Back’, a lacklustre thumper written in the waning days of Flip City. At least the story is compelling: a man is trapped in a relationship because of an unexpected pregnancy, though he tries his hardest to be honest (‘I wouldn’t say that I was raised on romance/Let’s not get stuck in the past’), before exclaiming to his girlfriend, ‘I love you more than anything in the world’. Before she gets comfortable with this unexpected outburst of romance, he’s quick to deliver the killer blow: ‘I don’t expect that will last’.

‘I’m Not Angry’ (Elvis Costello)

Lazy journalism often points at ‘I’m Not Angry’ as Elvis’s first declaration of anger, but this (incorrectly) assumes that Elvis is writing about himself. In fact, fans and critics alike would often try to create parallels with characters in Elvis’s songs that were either clearly fictitious creations or fabricated and distorted truths, done so to protect the innocent and guilty alike. ‘I’m Not Angry’ falls into the former category: the narrator is left to listen to an ex- girlfriend’s romantic encounter, done so in retribution, and all he can muster is a half-hearted shrug. Then again, he sure doesn’t sound like he’s over it, with Elvis’s sneering vocal delivery (matched in ferocity by John McFee’s snaking guitar), and methinks he doth protest his lack of anger too much in the last 50 seconds as the song fades out.

‘Waiting For The End Of The World’ (Elvis Costello)

Original album closer ‘Waiting for the End of the World’ was inspired by Elvis’s daily travels to and from work on the Underground: ‘a fantasy based on a real late-night journey’. This Dylan-esque rant throws a cast of train car characters into disarray by ‘pulling the hysteria out of newspaper headlines into the everyday boredom of the commuter’. Meanwhile, Clover’s plodding arrangement – Mickey Shine’s drums alone are apocalyptic – works to the song’s benefit, as John McFee’s pedal steel guitar snakes and slithers through Elvis’ verses and choruses. A fitting conclusion, the song’s power has since been diminished with ‘Watching The Detectives’ being retroactively promoted to album closer.

Related Tracks

‘Radio Sweetheart’ (Elvis Costello)

B-side of ‘Less Than Zero’, 25 March 1977.

Originally planned as Elvis’ debut single, ‘Radio Sweetheart’ would likely have ended his career before it even started – or, more charitably, his career trajectory would have been significantly altered. ‘Radio Sweetheart’ isn’t a bad song – far from it, with its clever wordplay and sprightly arrangement – but it was so out of touch with the musical landscape of 1977 and what Elvis would go on to do with The Attractions that its eventual home as the B-side of ‘Less Than Zero’ was for the best.

‘Watching The Detectives’ (Elvis Costello)

A-side, 14 October 1977; Peak position: 15.

A clatter of drums, a dub-inspired bass line, a vaguely jerky rhythm (not quite reggae, but a white English approximation thereof) are followed by one of the most instantly recognisable guitar riffs of Elvis Costello’s career – and all in the span of twenty seconds. ‘Watching The Detectives’ has achieved wide acclaim in Elvis’ career, and in the autumn of 1977, even became his first charting single. But its beginnings were certainly inauspicious: written in his front room in Whitton, ‘fuelled by nothing stronger than a jar of instant coffee after repeatedly listening to the first album by The Clash’, Elvis marvelled at that album’s production and wanted to do something similar. ‘Somewhere around dawn, the ‘Watching The Detectives’ story came into my mind. There were no barricades to mount in suburbia, no threat of riot, no hint of discontent.’

Elvis just so happened to have this song ready during auditions for his new backing band. Having played ‘Alison’ and ‘Less Than Zero’ endlessly with each candidate, Elvis broke up the monotony by teaching his borrowed support musicians – Graham Parker’s rhythm section Andrew Bodnar and Steve Goulding – this new song. Impressed with what he heard, Nick Lowe booked a session at Pathway Studios, eager to capture the song as quickly as possible. He had his own vision for the song, and ran the mics ‘hot’ to get the massive distortion in the introduction. Elvis later noted, ‘it was obvious from the first playback of ‘Detectives’ that this song was the real beginning of making records as opposed to just recording some songs in a room’. (Newly-hired keyboardist Steve Nason was called upon for keyboard overdubs; his Bernard Herrmann- inspired Vox Continental organ stabs were exactly what Elvis was looking for.)

Released as a non-album single in October 1977, ‘Watching The Detectives’ – backed with live recordings of ‘Blame It On Cain’ and ‘Mystery Dance’ (the first Attractions performances to be released on vinyl) – soared to fifteen in the UK, rewarding Stiff Records with their first Top Twenty single chart entry.

‘Stranger In The House’ (Elvis Costello)

A-side, 17 March 1978.

This outcast from the My Aim Is True sessions snuck out as a non-album bonus single with the first 50,000 copies of This Year’s Model. While more charitable fans would contest that this was due to Elvis wanting to give an extra bang for the buck, it’s just as equally a shrewd marketing ploy on Stiff Records’ behalf to drum up more sales of the new record. As with ‘Radio Sweetheart’, ‘Stranger In The House’ was intended for his debut album, though Elvis (correctly) reasoned that ‘including a country ballad was not thought to be a smart move in 1977’.

That didn’t stop the managers of country and western legend, George Jones, from suggesting that he and Elvis record a duet, with a recording session planned for July 1978. ‘Rumour had it that he was down in Florence, Alabama, and couldn’t come into the state, as one of his more famous exes was looking for alimony’, Elvis later wrote. ‘But maybe they told me this just to give me a taste of the Nashville soap opera mythology and make me feel better about making the trip in vain.’ The two finally recorded their vocal parts eight months later, and ‘Stranger In The House’ became a highlight of Jones’s 1980 album My Very Special Guests.

‘Neat Neat Neat’ (live) (Brian James)

Live recording B-side of ‘Stranger In The House’, 17 March 1978.

Originally recorded by The Damned and released as their second single in February 1977, Elvis and The Attractions (with Davey Payne on saxophone) included a live version of this song in their setlist on 22 October 1977, dedicated to Chris Miller (real name of Damned drummer Rat Scabies) who had just gotten into a scrape in London. Much like The Who extending a gesture of solidarity toward the incarcerated Mick Jagger and Keith Richards in the summer of 1967 (by recording ‘The Last Time’ and ‘Under My Thumb’), Elvis’ intentions were good, though the song ultimately amounts to a loud- sounding nothing, bathed in echo. This performance was later released as the B-side of the ‘Stranger In The House’ free giveaway single.