13,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Updated & revised edition of the history of todays illegals drugs. The text of Emperors of Dreams has been revised, updated and with new material added, it paints a fresh and startling picture both of today's illicit drugs and of the nineteenth century in general. Essential reading for anyone interested in the history of drugs and drugs policy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

“Jay is a valuable specimen of an unusual breed: a well-organised bohemian. He does not disdain conventional drug history, but he has absorbed it into a work that is literary in the broadest sense – rich in sociology and politics as well as in poetry and letters. In doing so, he has built a necessary bridge between scholarship and the illicit enthusiasm of drug culture.”

Marek Kohn in The Independent

“Emperors of Dreams should be mandatory reading for anyone concerned with drug legislation…Focusing on six drugs – nitrous oxide, cocaine, ether, opium, cannabis and mescaline – Jay builds up a picture of a world where drugs were much more freely available, but where problems associated with them were much less evident.”

Julian Keeling in The New Statesman

“Until a century ago, people had been able to go to the chemist for any number of pick-me-up or put-me-down potions, tonics and powders, containing various concentrations of opium, cocaine or cannabis…What this excellent book does is tell us how we got from there to here; and also how we got there in the first place…if you are not quite familiar with the subject, you really should read it.”

Nick Lezard’s Pick of the Week in The Guardian

“Splendid…shows how a huge cast of doctors, poets, authors, painters and even the odd Satanist experimented with everything from nitrous oxide (laughing gas) to cannabis and ether…Jay is particularly good on the predecessors of the campaigns that would culminate, in the late 20th century, in a hugely expensive and spectacularly unsuccessful War on Drugs.”

Joan Smith in The Independent on Sunday

“Intelligent and urbane…the first attempt to survey the nineteenth-century drug scene at large. Jay documents the prevalence of narcotics consumption (in those days, perfectly legal)…not only could poets wax lyrical about their properties, but distinguished public figures such as Willam Wilberforce were known to have an opium habit.”

Roy Porter in The Times Higher Educational Supplement

“Meticulously researched, compulsively readable and unfailingly fascinating…Jay uncovers the roots of 21st century psychoactive hedonism, and brings fresh insight to well-thumbed accounts of cannabis and opium use by such 19th century giants as Baudelaire and Coleridge.”

Gary Lachman in Fortean Times

The Author

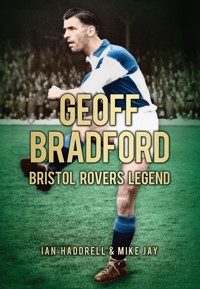

Mike Jay has written extensively on the history of science and medicine, and is a leading specialist in the study of drugs across cultures and throughout history.

His books on the subject include the anthology Artificial Paradises: A drugs reader (1999); The Atmosphere of Heaven (2009), which tells the story of the discovery of nitrous oxide; and High Society: Mind-altering drugs in history and culture (2010), which accompanied a major exhibition he curated at the Wellcome Collection in London.

His critical writing on drug literature and history has appeared in The Guardian, Telegraph, London Review of Books, Boston Globe and Notes and Records of the Royal Society. He is a trustee of the Transform Drug Policy Foundation and sits on the editorial board of the addiction journal Drugs and Alcohol Today.

His web site is http://mikejay.net

Contents

Title

Quotes

The Author

Preface to the New Edition

Introduction

‘O! Excellent Air Bag’: Nitrous Oxide

The Black Drop: Opium

The Seraphim Theatre: Cannabis

Attack of the Vapours: Ether and Chloroform

‘Watson, The Needle!’: Cocaine

A New Artificial Paradise: Mushrooms and Mescaline

Ardent Spirits: Temperance and Prohibition

Appendix: Selected Texts

Bibliography

Index

Copyright

Preface to the New Edition

This book was one of my first forays into the history of drugs. In the decade since it appeared I have returned to the subject many times, and I have taken the opportunity to revise the text in light of my subsequent studies. I have corrected errors of fact, lightly filled in some more social and biographical context, and qualified some of its judgements. Most of these changes are minor but their cumulative effect is (for me at least) a more satisfying read. I have also added new material that has come to light in the meantime: some of it from my own researches and some from the work of others, much of it outstanding, that has emerged over the last ten years. The cultural and literary history of drugs has been illuminated in important ways during this time: many new areas of enquiry have been opened up, and many paradigms shifted. I have indicated some of these new sources in an expanded bibliography.

Developments in contemporary drug culture have also thrown new light on the past. Patterns of drug use have become more complex, and new substances have proliferated through an increasingly globalised and informed subculture. In the last decade, for example, nitrous oxide has become established as a recreational drug in ways that recapitulate its use in the ‘laughing gas’ frolics of the early nineteenth century; the emergence of ketamine, a dissociative anaesthetic now widely adopted for non-medical purposes, suggests new perspectives on the experimental use of ether and chloroform in the Victorian era. Such fast-moving developments in the present are a reminder that our view of the past is in constant need of refocusing.

Broader social attitudes, too, have changed significantly. When this book first appeared, the history of drugs was largely written by doctors and historians with little curiosity about their subjective effects or the cultures that formed around them. Non-medical use was typically framed as ‘drug abuse’, and viewed either as pathology (‘addiction’) or a criminal and public health problem. As a result, I felt obliged to argue with the orthodox history in ways that now feel gratuitous. These older attitudes (now referred to by some academics, with splendid disdain, as ‘the twentieth century’s narcophobic discourse’) have been substantially overwritten by new work that is more interested in the drug experience, and informed by a wider public scepticism about the anti-drug pieties and propaganda of our contemporary politics. If this revised text feels slightly less polemical, it is not because my views have softened; they have simply become more commonplace.

September 2011

Introduction

Like most people, I grew up believing that drugs were a subject without a history. Almost everything I was taught, or read, or saw on television, implied that they were something new, a plague introduced into society by hippies in the 1960s. Occasionally the curtain was pulled a little further back to reveal glimpses of Victorian opium dens, or perhaps the use of toxic and stupefying plants by primitive people. But the implication was still that drugs, even if they’d been present in history, had always been illegal – at least as soon as societies had evolved far enough to make sensible laws. These substances had only ever existed in the shadows of civilisation, and no respectable person had ever been interested in them, with the exception of the doctors and police whose job it was to deal with them.

Since the sixties, this orthodoxy has been robustly challenged by revisionist views, but the alternative history they have generated tends to focus on the distant past: attributing the exclusion of drugs from Western culture to the efforts of the Catholic Church or the alcohol-fuelled warriors of the Roman Empire. Yet there is another history far closer to hand which shows that the very idea of drugs being illegal is an extremely recent one, dating back less than a century. In 1900, any respectable person could walk into a chemist’s in Britain, Europe or America and buy cannabis cigarettes, or tinctures of hashish premixed with opium extracts; they could choose cocaine either pure or in heavily-marketed product ranges of pastilles, lozenges, wines or teas; they could order exotic psychedelics such as mescaline or buy morphine and heroin over the counter, complete with hand-tooled syringes and injection kits.

Within the span of history this was only yesterday, and yet we hear very little of this recent story from either side of the highly polarised drug debate. For the sixties counterculture – or at least its cheerleaders and evangelists – it was important to stress that theirs was the first generation to discover drugs, and that this discovery marked an unprecedented, even evolutionary shift in human consciousness. Their opponents across the barricades were more than happy to collude in this rhetoric of novelty: it enabled them to stress the unprecedented threat that drugs represented, and the urgent need to commit suitable budgets and enforcement measures to turning back the tide.

And yet, throughout the reign of Queen Victoria and the height of Empire – an era regarded by many as the golden age of our civilisation – the West was awash with these substances; in fact, it was only when the dream of Empire began to fail that the movement to question their legitimacy began. In 1800, Humphry Davy’s reports of his experiments with nitrous oxide marked the beginning of the modern drug experience, and by 1821 Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater had brought the exploration of their effects into mass popular culture. Yet it was only after 1900 that efforts to prohibit drugs began to take hold at an international level, and not until 1921 that these efforts were fully enshrined in British law. The century in between, typically regarded as an era of moral probity and social control, could also be billed as ‘Drug Legalisation: The First Hundred Years’.

This is the century on which this book focuses, and its aim is to trace the origins of the drugs that appeared in the West during that time. How did these substances, now an illicit, multi-billion-dollar global phenomenon, first arrive in the modern world? Who were the first people to experience their effects, how were these effects originally interpreted, and how did they spread into the broader culture? My primary motive for this enquiry is simply amazement that these pioneer stories are so rarely told: this is the first volume in English to relate them all together in any detail. Not only are these early encounters crucial to our understanding of what these drugs are and how and why people use them, but they also plumb a fabulously rich vein of explorers’ tales, secret histories and weird scenes that combine to assemble a hallucinatory alternate narrative of the nineteenth century itself.

I have traced these stories with the drugs in question as the protagonists, following their arrival and picaresque progress through a world that was as new to them as they were to us. In the period from 1800 to 1900, the discovery of drugs continually mirrored other transformations in art, science, commerce and society, and vigorously encouraged them with new and mind-expanding experiences which – farcical or profound, courageous or deranged – demonstrated repeatedly that human consciousness might include dimensions previously undreamed of. Most historical work on drugs in the nineteenth century to date has shown little interest in the visions and subcultures they generated, concentrating instead on processes such as their supply, commoditisation, public perception or statutory control. These are all important elements of the story, but my aim here also includes building up a picture of the subjective world opened up by each drug and its meaning for those who took it. Without this dimension, the responses of the drugtakers of the nineteenth century are too easily dismissed as self-indulgent, aberrational or pathological; with it, we begin to sense the courage – or hubris – that was required not to dismiss these novel states of consciousness but to explore them further, to attempt the task of explaining them to the sober world, and to seek new roles for them – scientific or poetic, medical or social – within it.

Drugs, both in their externally observable form as exotic commodities and their private role as agents of altered consciousness, attached themselves to many of the nineteenth century’s great themes. As science evolved, they offered new tools to explore the mysteries of the mind, and new dangers as medicine struggled with sinister paradigms of mental illness and degeneration. Drugs discovered in the process of colonial expansion became global economic forces, devastating weapons in the free trade wars and, increasingly, symbols for the fear that the cultures subjugated by the West might find ways of turning the tables and enslaving their captors. Within the worlds of art and thought, drugs emerged from an Enlightenment quest to understand the workings of the mind into a Romantic or Transcendentalist search for subjective truth beyond the measurable, and eventually into a fin-de-siècle celebration of the irrational and the forces of the unconscious. Consequently this is not exactly a history of science, nor a work of literary reference, nor a social history, but a combination of these and other investigations swimming within a broader current of evolving ideas.

The eventual prohibition of drugs gives many (though not all) of the stories in this book a classical three-act dramatic structure. In the first act, the drug is discovered and its novelties and benefits celebrated; in the second act, it escapes from the laboratory and makes its idiosyncratic journey through the byways of nineteenth-century society; in the third act, the powers that be unite in their attempt to extinguish it. It is, of course, the narrative of Frankenstein. But the terminal destination is by no means the whole journey, and in itself this conclusion tells us little about the extraordinary story of the century before. During the nineteenth century drugs were hailed by scientists as the crowning glories of the modern age, and praised by artists and philosophers as the keys to transcendental realms beyond religion; promoted by doctors as the solution to the crises of modern life, and demonised by politicians as the agents of sinister conspiracies against civilisation itself. Above all, then as now, they were increasingly passed around among ordinary people, along with a gradually evolving lore of their pleasures and pains, their uses and abuses, and with an ever-watchful eye on a state that, as its powers grew, sought to control and eliminate them.

I’d like to thank many people for their time, encouragement and help with notes and queries, including: Miranda Bennion, John Birtwhistle, Mike Blackburn, Sam Bompas, Louise Burton, Paul Cheshire, Bal Croce, Edward Featherstone, Juri Gabriel, Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Anthony Henman, Robert Irwin, Jimmy Kempfer, Danny Kushlick, Gary Lachman, Eric Lane, Marie Lane, Howard Marks, John Marks, Antonio Melechi, Barry Milligan, Michael Neve, Russell Newcombe, Charles Peltz, Steve Rolles, Richard Rudgley and Sophie Stewart.

‘O! Excellent Air Bag!’

Nitrous Oxide

On Boxing Day of 1799 the twenty-year-old chemist Humphry Davy – later to become Sir Humphry, inventor of the miners’ lamp, President of the Royal Society and domineering genius of British science – stripped to the waist, placed a thermometer under his armpit and stepped into a sealed box specially designed by the engineer James Watt for the inhalation of gases, into which he requested the physician Dr. Robert Kinglake to release twenty quarts of nitrous oxide every five minutes for as long as he could retain consciousness.

The experiment was taking place in the lamp-lit laboratory of the Pneumatic Institution, an ambitious and controversial medical project where the young Davy had been taken on as laboratory assistant. It had opened the previous month in Hotwells, a rundown spa settlement at the foot of the Avon Gorge outside Bristol. Originally set up to rival nearby Bath, Hotwells had dwindled to a downmarket cluster of cheap clinics and miracle-cure outfits offering hydrotherapy or mesmerism to those in the desperate last stages of consumption; but the Pneumatic Institution was a new arrival with revolutionary ambitions. Its founder, the brilliant but maverick doctor Thomas Beddoes, believed that the new gases with which he and his assistant were experimenting had the power to put the treatment of this most lethal of diseases onto a proper scientific footing for the first time, and in the process to transform the art of medicine.

In the centre of the laboratory, Davy had set up a chemical reaction: nitrate of ammoniac bubbled in a heated retort, and the escaping gas was being collected in a hydraulic bellows before seeping through water into a reservoir tank from which the sealed box was being filled. After an hour and a quarter, by which time he estimated that his system was fully saturated, Davy stepped out of the box and proceeded to inhale a further twenty quarts of the gas from a series of oiled green silk bags.

As Davy had been seated in the box, breathing deeply, he had felt the effects of the gas that had become familiar from his many previous experiments since he had discovered it in April of that year. The first signature was its curiously benign sweet taste, followed by a gentle pressure in the head as he continued to inhale. Within thirty seconds the sensation of soft, probing pressure had extended to his chest, and the tips of his fingers and toes. This was accompanied by a vibrant burst of pleasure, and a gradual change in the world around him. Objects became brighter and clearer, their perspectives quietly shifting, the sense of space in the cramped box expanding and taking on unfamiliar dimensions.

Now, under the influence of the largest dose of nitrous oxide anyone had ever taken, its effects were accelerating to levels he had never imagined. His hearing became fantastically acute: he could distinguish every sound in the room and, as he concentrated on the echoing babble, he began to sense that he was hearing sounds from far beyond the room – a vast and distant cosmic hum, the vibration of the universe itself. In his field of vision, the objects around him seemed to be teasing themselves apart into shining packets of light and energy. He felt the gas diffusing inside him, inflating him to something far beyond the man he had been an hour before. He was rising effortlessly into new worlds, whose existence he had never suspected. Somehow, the whole experience was irresistibly funny: he had ‘a great disposition to laugh’, as all his senses competed to exercise their new-found freedom to its limit.

As these new realms of experience opened up before him, Davy suddenly ‘lost all connection with external things’, the forces erupting within his mind eclipsing the two-dimensional shadowplay of the laboratory. Here, thoughts and ideas played across his consciousness at lightning speed: ‘vivid visible images’ presented themselves to him in rapid succession, illuminating patterns and connections previously unimagined. Flashes of insight broke like thunder and lightning around him, ideas crackling across spark-gaps to illuminate an understanding of the universe vaster than either his science or his poetry had ever conceived. To breathe the gas was, simply and literally, inspiration.

After an eternal moment Davy felt the bag being removed from his lips and became aware of Dr. Kinglake leaning over him with a physician’s solicitous manner. The sight of his colleague, coming as it did at the peak of his cosmic journey, struck him forcefully with a combination of emotions. First, indignation that this mere mortal had made the decision to remove the air-bag – a decision taken in ignorance of the uncharted landscape through which Davy was travelling. Next, an irresistible superiority to this comical functionary fiddling with gas-bags and medical apparatus without the faintest idea of the brave new world at whose portals he was officiating. As his situation impressed itself upon him, he cast around for a sentence to encapsulate what he had experienced in the impossibly short time he had been away. It was like trying to cram an ocean into a teacup: the more he tried to formulate what he had seen, the more he felt it ebbing away, back into the dimension from which he was returning. Davy paced, ignoring everything, trying to take a grip on the essence of what had happened to him before it slipped away entirely. After a minute or so he turned to Kinglake and addressed him with ‘the most intense belief and prophetic manner’ he could muster:

‘Nothing exists but thoughts!’ he pronounced. ‘The Universe is composed of impressions, ideas, pleasures and pains!’

For many pioneers of science, the ‘eureka moment’ on which their fame rests is an artefact of hindsight, a neat tale confected only after the import of their discovery had been recognised. Not so for Humphry Davy. His nitrous oxide experiments, culminating in the final days of the eighteenth century, had opened up a new method of scientific enquiry, and had been rewarded with a vision that would transform science in the century to come.

Mind-altering drugs were not new: at the time when Davy performed his experiment, people had been taking intoxicating plants for this purpose since time immemorial. In Mexico, the Huichol were making their annual migration to gather the peyote cactus; in Africa, the Bwiti cult were initiating their young men with the ibogaine root; across the Arctic north, from Lapland to Siberia, shamans were employing the fly agaric mushroom in their ecstatic spirit-journeys. But Davy’s experiment marks a radically new approach to drugs and their transforming effects on the mind. Pure nitrous oxide, a substance not found in nature, had only existed for a few years, its effects on consciousness entirely unknown. Never before had a mind-altering chemical been deliberately ingested, first by its discoverer and then by a brilliant circle of scientists, philosophers and poets, in a systematic exploration of its effects. In the same way that the material world was being remade by scientific progress, they were claiming that science could also remake the parameters of human possibility from the inside out.

However intoxicating the destination, Davy had reached it by following the sober path of science. The study of drugs had, until this point, been a miasma of facts and fancies, tales of dreams and visions, illusions and madness, secrets and potions, compendia of poisons and herbal lore, morality plays of the devilish and the divine. But he and Thomas Beddoes had isolated the gas by the empirical method: observation, repetition, the careful whittling away of extraneous factors until the skeleton of cause and effect was rendered clearly visible. They had synthesised it under controlled conditions, and rigorously tested its properties and nature: on dead and living tissue, on animals, and finally on themselves. When Davy had first inhaled it from his silk bag, he had shifted the arena of his research from the chemical apparatus in front of him to the inner laboratory of his own mind. But to make this leap required a combination of at least three disciplines, all of which both Beddoes and Davy happened to possess to a high level: chemistry, medicine and poetry.

It is as a chemist that Humphry Davy is best known, and it is as a chemist that he enters the frame of this story. He grew up in the provincial backwater of Penzance at the tip of Cornwall, a small fishing, mining and smuggling community about as remote from the mainstream of British public and scientific life as it was possible to be. His local mentors were the conservative stalwarts of the community, for whom a medical career was the proper and realistic way of entering the professional classes; but Davy’s early aptitude lay in the groundbreaking modern discipline of chemistry, which he taught himself to a remarkable standard from a couple of basic textbooks. Here, the isolation of gases was one of the recent discoveries that was reshaping the modern understanding of the world. The French chemist Antoine Lavoisier had isolated oxygen in 1775, three years before Davy’s birth; in the process he had shown it was oxygen that caused substances to burn in the air, and made possible all the dynamic processes that sustained life.

The isolation of oxygen developed in tandem with the discovery of various other gases, including nitrous oxide, which was first isolated (though not inhaled) by the prodigious experimental chemist Joseph Priestley in 1774. It had subsequently attracted the attention of an American chemist, Samuel Latham Mitchill, who theorised that it was a dark counterpart to oxygen, a sinister substance that brought death where oxygen brought life. It was nitrous oxide, Mitchill claimed, that was responsible for the processes of disease and decay: an invisible miasma, present everywhere in small concentrations, that disintegrated living tissue and fed the process of putrefaction. He christened it ‘septon’, the ‘Great Disorganiser’ – and, in homage to the scientific poet Erasmus Darwin, described its effects in verse:

‘Grim Septon, arm’d with power to intervene And disconnect the animal machine’

Davy encountered Mitchill’s theory while still in his teens; he was immediately sceptical and set out to disprove it. He synthesised nitrous oxide, ran tests on animals and established quickly that, although nitrous oxide could not support life without oxygen, it was no more putrefying than air itself, and that air without nitrous oxide was still a sufficient medium for tissue decay. He was confident enough of his conclusions to take a small whiff of the alleged deadly poison himself, though not yet curious enough to inhale further.

It was at this point that the teenage prodigy happened to come to the attention of the only man in the area who could offer him an alternative to the solid but dull career of a provincial doctor: an engineer named Davies Giddy who had studied chemistry at Oxford under the University’s resident expert, Dr. Thomas Beddoes. Aware that Beddoes required a laboratory assistant for his new venture, the Pneumatic Institution in Bristol, Giddy recommended Davy for the post.

It was with Beddoes that the second discipline required for the nitrous oxide experiments came into play: medicine. Davy, experimenting with the gas as a chemist, had not entertained the idea of shifting the focus of his experiments to his own body. Beddoes, however, was not only a leading authority on the new chemistry but also a doctor who had been applying the recently-discovered gases to human subjects in the search for new medical treatments. For him, the new gases were as radical a discovery for medicine as they were for chemistry.

In 1793, after several years of teaching chemistry at Oxford, Beddoes had resigned his post. An outspoken political reformer, he had welcomed the French Revolution in 1789 and, just as it was descending into bloodshed and war with Britain, had written a series of pamphlets in its support that marked him, in the eyes of the Oxford establishment, as a political undesirable. But his reforming zeal was not limited to politics: indeed, its relentless focus was the medical profession. He had qualified as a physician at Edinburgh University but had developed a deep scepticism about the way the profession operated. The vast majority of doctors treated symptoms rather than researching cures, and attended the wealthy at the expense of the majority. ‘The sick and drooping poor’, as Beddoes called them, were a constant reproach to the pretensions of modern medicine, and alleviating their suffering was the only activity that deserved the name of progress.

But there was one school of medicine for which Beddoes had great enthusiasm: the ‘Brunonian’ system developed by the Scottish doctor John Brown. Brown had, like Beddoes, studied at Edinburgh, but on qualifying had dramatically rejected his schooling and devised an alternative that rendered orthodox medicine redundant. No matter how sophisticated the theories of the medical profession, they were limited by the number of effective medical treatments at their disposal, which were very few. Brown’s system reconstructed medical treatment from the bottom up by starting with the handful of therapies that actually worked, and classifying diseases accordingly. This led him to propose a scheme of the greatest possible simplicity. All illnesses, in his system, were characterised either by overstimulation or understimulation of the basic nervous system; consequently treatment should either stimulate the depressed system, or depress the overstimulated system. The classic stimulant was alcohol; the classic depressant, opium.

The Brunonian system offered a root-and-branch overhaul of the emerging medical science, and one that aimed to put medical treatment back in the hands of the people. Diagnosis and prescription would become little more than common sense, and slim Brunonian manuals would take the place of the swelling ranks of doctors. To most doctors it was a disreputable anti-medical cult, but for Beddoes, despite its undoubted oversimplifications, it was the only system that offered a practical bedrock to build on. The pressing need was to extend the range of treatments: to discover more Brunonian stimulants and depressants, observe their effects and develop their applications. Beddoes had already been researching the medical use of oxygen before he left Oxford, and when he left he decided to devote himself entirely to the project.

Today, we would call the Pneumatic Institution a medical research laboratory; in 1793, it was a project without precedent. Gases, still often referred to as ‘factitious’, or artificial, ‘airs’, were a novelty and to most a mystery: invisible, intangible, and the subject of many . fantastical theories. Applying them to medicine was contentious, as was any experiment on human subjects, and the project’s Brunonian agenda made the Pneumatic Institution deeply suspect to the medical establishment. Beddoes had applied to the Royal Society for funds, but its president, Sir Joseph Banks, had turned him down, refusing to lend even the Society’s name to the scheme. In the end Beddoes’ funding and support had come not from the scientific or metropolitan elite, but from provincial industrialists, dissenters and nonconformists such as James Watt and the Wedgwood pottery dynasty.

The Pneumatic Institution was both laboratory and hospital, serving Beddoes’ primary directive of treating the poor at the same time as researching and developing new medicines and advertising the revolution in treatment it hoped to offer. Davy’s talent for chemistry was now in harness to a medical programme, where the newly synthesised gases would be tested first on animal and then on human subjects. Nitrous oxide was among the first of the ‘airs’ he produced in April 1799, repeating his earlier experiments in Penzance, but this time with a new interest in its effect on the human constitution. With his first lungful of the gas, he felt the presentiments of the intoxication to come – a ‘slight degree of giddiness’ and an ‘uncommon sense of fullness in the head’. These passed quickly, but this time they awakened a curiosity in Davy that was more than medical, and he asked Dr. Beddoes to join him for a further, more intensive trial. Filling his lungs from a green silk bag, Davy felt for the first time the ‘highly pleasurable thrilling in the chest and extremities’ that announced a rising surge of physical energy and a burst of euphoria that sent him leaping and whooping around the laboratory.

Davy’s, and Beddoes’, curiosity about the psychoactive effects of the gas had also been stimulated by their shared interest in the third discipline that would drive their experiments: poetry. Beddoes was an enthusiastic poet, an art for which his son Thomas Lovell Beddoes would become famous. He was also Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s doctor, and a contributor to Coleridge’s revolutionary journal The Watchman. Coleridge’s close friend and collaborator Robert Southey was also among Beddoes’ protégés, and had become passionate friends with Davy, for whom poetry was as intense a passion as chemistry: when not in his childhood laboratory, his greatest joy had been declaiming his wild nature verses from the Cornish cliffs and headlands. For this new generation of poets, science was a revolutionary fellow-traveller with their art, opening nature up to scrutiny in ways that paralleled their own. Coleridge in particular was fond of scientific coinings: he would describe someone in a fiery rage as ‘filled with phlogiston’, and would later attend Davy’s lectures in London ‘to replenish my stock of metaphors’. He also, more enduringly, coined the term ‘psychosomatic’, a fine description of many of his own most painful conditions.

From early in their acquaintance, Davy, Coleridge and Southey were deeply involved in subjecting the essence of nature to the twin probings of science and poetry. All had been enraptured by classical myths and The Arabian Nights as children, and all maintained their fascination with dreams and visions to the end of their lives. The poets looked to science to provide a new language for ideas previously inexpressible; Davy looked to poetry to express the sublime and complex visions that the scientific method revealed. Davy, Coleridge would later say, was ‘the father and founder of philosophical alchemy, the man who born a poet first converted poetry into science’; and Davy’s youthful poetry hymned the science that allowed him ‘on Newtonian wings sublime to soar’.

Within days of Davy’s first trial, he offered the gas to Robert Southey, whose reaction did not disappoint. His ecstatic letter to his brother after inhaling it for the first time set the tone for the explorations which were to follow:

“O, Tom! Such a gas has Davy

discovered, the gaseous oxyd! O, Tom!

I have had some; it made me laugh and

tingle in every toe and finger-tip. Davy

has actually invented a new pleasure

for which language has no name. O,

Tom! I am going for more this evening;

it makes one strong and so happy, so

gloriously happy! O, excellent air-bag!

Tom, I am sure the air in heaven must

be this wonder-working air of delight!”

Only a few days before, nitrous oxide had been ‘grim Septon’, the universal toxin, agent of all pestilence and decay; now it was, in Davy’s words, the ‘pleasure-producing gas’, and as such began to make its chaotic and ecstatic inroads through the Bristol circle. Scientific self-experimentation had demonstrated, for the first but not the last time, that the theories of a substance’s likely effect, even those of its discoverer, are no match for the direct experience of the substance from within. Armed with the new gas, with dreams of a revolutionary new medicine and a passion for exploring the worlds of the imagination, Davy and his associates would attempt to weld the languages of science and poetry together to describe the indescribable.

And so, in the early summer of 1799, the nitrous oxide trials began. In the evenings, after the clinic had closed and the animal experiments were finished, the nitrate of ammoniac reaction would begin to bubble in the upstairs drawing room as the circle made repeated trials on themselves and each other: doctors and patients, men and women, chemists, playwrights, surgeons and poets. Davy was master of ceremonies and also, by his own account, inhaling the gas three or four times a day. The laboratory became a philosophical theatre in which the boundaries between experimenter and subject, spectator and performer were blurred to fascinating effect, and the experiment took on a life of its own.

Although the trials commenced within a medical framework, they came to focus increasingly on questions of philosophy and, in particular, language. Davy was struck by the poverty of the ‘language of feeling’, the awkwardness of the subjects’ attempts to put their inner revelations into words. The standard medical question, ‘how do you feel?’ in this context took on imponderable, existential dimensions. He was struck by the poverty of one of the clinic patient’s answers to this question: ‘I do not know, but very queer.’ The patients were not mentally impaired by the gas, but overstimulated beyond the reach of words themselves: as Davy himself put it, ‘I have sometimes experienced from nitrous oxide, sensations similar to no others, and they have consequently been indescribable.’ James Thompson, one of the experimental subjects, captured the magnitude of the task precisely: ‘We must either invent new terms to express these new and peculiar sensations, or attach new ideas to old ones, before we can communicate intelligibly with each other on the operation of this extraordinary gas.’

Davy instituted a loose reporting protocol, asking every volunteer to produce a short written description of their experience. Some subjects produced answers that were oblique but highly imaginative: another of the clinic’s patients answered ‘how do you feel?’ with ‘I feel like the sound of a harp’. Musical analogies emerged repeatedly, attempting to catch the aural effect of ringing harmonics that often accompanies the rush of nitrous oxide intoxication. Beddoes, emerging from a deep immersion, once shouted out the single word ‘Tones!’ This seemed to connect to sublime images that were simultaneously appearing in the poetic writings of Coleridge and his friends: the Aeolian wind-harp, for example, which is played by no one, but draws its harmonies directly from Nature herself.

One frequent, though not universal, response to the gas was the sensation of intense and voluptuous pleasure. Dr. Stephen Hammick, a surgeon from Plymouth Hospital, recorded that ‘I had not breathed half a minute when, from the extreme pleasure I felt, I unconsciously removed the bag from my mouth; but when Mr. Davy offered to take it from me, I refused to let him have it, and said eagerly, ‘Let me breathe it again, it is highly pleasant, it is the strongest stimulant I ever felt!’’ Coleridge, on his third trial, noted that ‘towards the last I could not avoid, nor felt any wish to avoid, beating the ground with my feet; and after the mouthpiece was removed, I remained for a few seconds motionless, in great ecstacy.’ How could it be that a factitious gas, unknown in nature, could so reliably, even mechanically, generate such peaks of delight?

Coleridge’s account of his compulsive foot-stamping points to another response that recurred frequently (though by no means invariably) through the trials: ‘antic’ behaviour, the acting out of bizarre and unconscious impulses. James Tobin, a local physician, recalled that, ‘When the bags were exhausted and taken from me… suddenly starting from the chair, and vociferating with pleasure, I made towards those that were present, as I wished they should participate in my feelings. I struck gently at Mr. Davy and a stranger entering the room at that moment…I then ran through different rooms in the house, and at last returned to the laboratory somewhat more composed.’ Beddoes’ father-in-law, Sir Richard Edgeworth, ‘capered around the room without having any power to restrain himself’; one anonymous young lady became a ‘temporary maniac’ who dashed out of the laboratory and into the street where she ‘leaped over a great dog in her way’. These effects sit oddly with the later application of nitrous oxide as an anaesthetic, but ‘antic’ and impulsive physical actions would would turn out, paradoxically, to be the route by which its anaesthetic properties would be discovered.

Alongside the distractions and laughter, the gas also delivered sensations that were genuinely sublime, though profound insights would remain curiously inseparable from the ecstasy and hilarity. One of the most striking descriptions was offered by Peter Mark Roget, a young physician who was already working on lists of synonyms that would, many years later, emerge as Roget’s Thesaurus. ‘My ideas succeeded one another,’ he wrote, ‘with extreme rapidity, thoughts rushed like a torrent through my mind, as if their velocity had been suddenly accelerated by the bursting of a barrier which had before retained them in their natural and equable course.’ This metaphor of drugs flooding the brain with perceptions that are usually edited from consciousness was recapitulated in Aldous Huxley’s Doors of Perception, and modern neurochemistry suggest it may be something more than a metaphor: substances such as nitrous oxide do indeed work by flooding the brain with excitatory neurotransmitters. The ‘language of feeling’ was, perhaps, capable of generating insights ahead of its time.

As the summer wore on, the scene in the Pneumatic Institution’s laboratory came to seem less like a medical experiment and more like a sanctum for untrammelled personal freedom. Normal social rules were replaced by a code where those in the thrall of the gas were left undisturbed in their reveries, excused almost any antisocial behaviour, encouraged to express random-seeming thoughts and actions and attended to carefully as they chanelled its revelations. Despite the rubric of empirical science and the ambitions to medical therapy, observers reported scenes closer to the religious rites of spirit possession, trance, oracles or speaking in tongues. The novelist Maria Edgeworth, daughter of Sir Richard, visited to observe the ‘wonders’ at the Institution and concluded that ‘pleasure even to madness is the consequence of this draught’.

Davy also took enthusiastically to experimenting on his own. On full moon nights in particular, he would wander down the Avon Gorge with a bulging green silk air-bag and notebook, inhaling the gas under the stars and scribbling snatches of poetry and philosophical insight. On one occasion he made himself conspicuous by passing out and, on recovery, was obliged to ‘make a bystander acquainted with the pleasure I experienced by laughing and stomping’. He noted an element of compulsion in his use, confessing that ‘the desire to breathe the gas is awakened in me by the sight of a person breathing, or even by that of an air-bag or air-holder’. He began, too, to push his experiments into more dangerous territory. He tried the gas in combination with different stimulants: he drank a bottle of wine methodically in eight minutes flat, and then inhaled so much gas he passed out for two hours. He also experimented with nitric oxide, which turned to nitric acid in his mouth, burning his tongue and palate, and with ‘hydrocarbonate’ – hydrogen and carbon dioxide – which left him comatose, the air-bag fortunately falling from his lips. On recovering, ‘I faintly articulated: “I do not think I shall die’’.’

By the end of the summer, the energy of the trials was dissipating: for most of the volunteers, the novelty of the experience wore off after a few sessions. Davy’s experiments became increasingly solitary, partially focused on resolving technical questions of how much gas was absorbed into the bloodstream and whether it should be classified in Brunonian terms as a stimulant or a sedative, but also searching for a framework – scientific, poetic or philosophical – to account for its effects. In this he was encouraged by Coleridge, who returned in October from an extended visit to Germany, bringing news of the new idealistic turn in German philosophy: the theories of Immanuel Kant and the emerging Naturphilosophie that the world of ideas was the ultimate reality, and the material world only an illusion projected by the mind. The dissociative effects of nitrous oxide, with its sense that the mind was no longer anchored to the physical body, made a compelling fit with such philosophies; and Davy’s climactic revelation that ‘nothing exists but thoughts’ would echo them through the century to come.

Despite their often chaotic melange of hedonism, heroism, poetry and philosophy, Davy’s report on the trials, when it emerged, made a powerful case for their scientific worth. After his climactic Boxing Day experiment, he began writing at top speed and by Easter of 1800 had produced a 580-page monograph on the new gas and its effects. Under the businesslike title Researches, Chemical and Philosophical; chiefly concerning Nitrous Oxide, or dephlogisticated nitrous air, and its Respiration, he described the synthesis of the gas, its effect on animals and animal tissue and, in an unprecedented final section, the descriptions of the subjective effects of nitrous oxide intoxication on himself, Beddoes and another two dozen subjects, including Coleridge and Southey. It was a report that combined two mutually unintelligible languages – organic chemistry and subjective reportage – to create a new hybrid, a poetic science that could encompass both the chemical causes of the experience and its philosophical consequences.

Davy’s Researches announced him to the scientific world as an outstanding chemist, but they were less kind to the reputation of the Pneumatic Institution. His book downplayed the project’s original focus on medical treatments in favour of the quest to unravel the effects of nitrous oxide on the mind, the emotions, the senses and the subjects’ perception of the world around them. Davy’s original dedication of the monograph to Beddoes was removed just before publication, suggesting a last-minute realisation that the finished work had strayed further from the medical ambit than originally planned. The effect was that, while Davy’s career soared, the reputation of the Pneumatic Institution plummeted. Its quest to introduce ‘factitious airs’ into medical treatment was regarded as a dead end and, over the following decades, largely forgotten.