11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

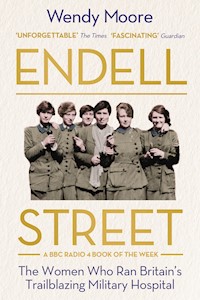

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A BBC RADIO 4 BOOK OF THE WEEK When the First World War broke out, the suffragettes suspended their campaigning and joined the war effort. For pioneering suffragette doctors (and life partners) Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson that meant moving to France, where they set up two small military hospitals amidst fierce opposition. Yet their medical and organisational skills were so impressive that in 1915 Flora and Louisa were asked by the War Ministry to return to London and establish a new military hospital in a vast and derelict old workhouse in Covent Garden's Endell Street. That they did, creating a 573-bed hospital staffed from top to bottom by female surgeons, doctors and nurses, and developing entirely new techniques to deal with the horrific mortar and gas injuries suffered by British soldiers. Receiving 26,000 wounded men over the next four years, Flora and Louisa created such a caring atmosphere that soldiers begged to be sent to Endell Street. And then, following the end of the war and the Spanish Flu outbreak, the hospital was closed and Flora, Louisa and their staff were once again sidelined in the medical profession. The story of Endell Street provides both a keyhole view into the horrors and thrills of wartime London and a long-overdue tribute to the brilliance and bravery of an extraordinary group of women.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Wendy Moore is a freelance journalist and author of four previous non-fi ction books on medical and social history. Her second book, Wedlock, was a Channel 4 TV Book Club choice and a Sunday Times number-one bestseller. She lives in London.

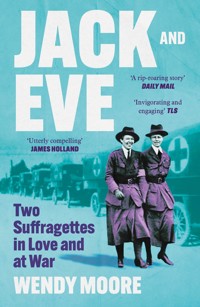

ALSO BY WENDY MOORE

The Knife Man

Wedlock

How to Create the Perfect Wife

The Mesmerist

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.This paperback edition fi rst published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books

Copyright © Wendy Moore, 2020

The moral right of Wendy Moore to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.Every eff ort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 585 3Ebook ISBN: 978 1 78649 586 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Jennian

Guide, mentor and friend

And for all the women who worked at Endell Street and

all the men and women who were treated there

Contents

Arrivals

1: A Good Feeling

2: A Sort of Holiday

3: Sunshine and Sweetness

4: Good God! Women!

5: Serfs and Slaves

6: Almost Manless

7: Pioneers, O Pioneers!

8: The March of the Women

9: Darkest Before Dawn

10: Full of Ghosts

11: The Soft Long Sleep

Acknowledgements

Notes

Select Bibliography

Picture Credits

Index

Arrivals

Covent Garden, London, 1915

IT WAS LIKE slipping into a dream. Or waking from a nightmare. They had grown used to the constant thunder of shelling, the crackling of rifles and machine guns, the screams and groans of their comrades. Now all they could hear was the gentle thrum of the city at night as they rumbled through dark, deserted streets. For months they had known only the rural landscape of France and Flanders, where every living thing had been crushed and obliterated into the mud of the trenches and shell holes. Now they found themselves being driven down a narrow street of tall buildings which blotted out the night sky. They had been living in a world peopled by men. Now they entered a world run solely by women.

They did not know how to react. Most of them were young men in their twenties and thirties; some were just boys in their late teens. Officially they were meant to be at least nineteen to be sent overseas to fight but some had lied about their age. Many had signed up in bands of friends in a fit of patriotic zeal or shown up shamefaced at a recruitment office after being challenged with a white feather by a stranger in the street. For some of them, being injured had come as a blessing – a ‘Blighty wound’ that allowed them to escape the death and devastation of war. For others, their injuries meant a new kind of terror and fear for the future: the prospect of never working, perhaps never walking, again, the possibility of perpetual pain, of permanent disfigurement. They had suffered long and agonizing journeys, having been scooped up from the battlefield by regimental stretcher-bearers, sometimes after lying abandoned for hours in ‘no man’s land’, before being shuttled back to casualty posts in tents and dugouts for basic first aid, a shot of morphine and, perhaps, a hurried operation. They had been transported in ambulance trains to one of the French ports, crammed into hospital ships to cross the Channel, then packed into Red Cross trains bound for London. Arriving at one of the mainline stations, they had been collected by volunteers who drove them in ambulances or private cars across town. If they asked their drivers where they were being taken, they were told to ‘the best hospital in London’.

When they pulled up outside the old workhouse building in Endell Street, in the heart of London’s theatreland, the great black iron gates were opened by a woman in a military-style jacket and ankle-length skirt. The ambulances juddered to a halt in the dimly lit courtyard and then women stretcher-bearers, wearing the same military-style uniform, carried the men to a lift. When they arrived on one of the wards, they saw a room bright with coloured blankets and fragrant with fresh flowers. While faces stared at them from crisp white pillows, they were lifted onto coarse blankets protecting the beds from their muddied and bloody uniforms. They were surrounded, naturally enough, by female nurses, orderlies and clerks. Then the doctors arrived. And all of these were women too. From the physician who assessed their condition to the surgeon who inspected their wounds, from the radiologist who ordered X-rays to the pathologist who took swabs, from the dentist who checked their teeth to the ophthalmologist who tested their sight, every one of the doctors was female. With the sole exception of the burly policeman at the entrance and a handful of male orderlies who were too old or too infirm for combat, the Endell Street Military Hospital was staffed entirely by women.

For some of the men who arrived at Endell Street on one of those dark nights, with their uniforms stinking of the trenches, entering this female world was a blessing. It was a glorious relief to be surrounded by women after all the hell that was being unleashed by men in France and beyond, a comforting reminder of their old lives with their mothers, sisters and sweethearts. For others it was a threatening, shocking, even distressing experience. Women nurses were one thing. Many of the men had already had their wounds dressed by female nurses in field hospitals and on ambulance trains. Women doctors were something else entirely. None of them had ever been treated by a female doctor in civilian life – the idea of women providing medical care to men was simply unheard of – and they knew full well that women doctors were not ordinarily employed in the army. Some of the men had wounds in intimate places, while others had contracted venereal diseases after sexual encounters with women in France. A few were convinced they had been sent to Endell Street to die, that they were hopeless cases. For why else would the army despatch them to a hospital run solely by women and not just any women but suffragettes, former enemies of the state? Indeed, one young soldier who had panicked on finding himself surrounded by women on arrival at Endell Street requested a transfer elsewhere. But he just as quickly changed his mind – and asked his mother to plead for his return.

For as they soon discovered, from talking to the other patients on their homely wards, or in the recreation room stuffed with books, or in the courtyard filled with plants and striped umbrellas, the ‘Suffragettes’ Hospital’ as it was commonly known, or the ‘Flappers’ Hospital’ as it was sometimes nicknamed, was universally popular. Endell Street Military Hospital, as it was formally titled, was indeed – they all agreed – the best hospital in London.

CHAPTER 1

A Good Feeling

Victoria Station, London, 15 September 1914

LOUISA GARRETT ANDERSON and Flora Murray waited impatiently to board their train. Tall, slim and erect in the midst of the fourteen younger women who were going with them, they exuded calm authority. Everyone had come to see them leave – family, friends and comrades from the suffragette movement – and to ply them with gifts. One well-wisher had arrived with three boxes packed with provisions for the journey while others brought fruit, chocolates and flowers. Surrounded by their hand luggage, the women looked awkward in their stiff new greyish-brown uniforms, their ‘short’ skirts just covering the tops of their ankle boots, their belted tunics buttoned firmly up to their necks. Their main luggage had already been stowed and would be waiting for them on arrival – or so they thought.

Victoria Station was bustling. In the six weeks since war had been declared, the railway terminus had been transformed. Among the commuters pouring off the trains for their daily drudgery in the city, there were Belgian refugees who had fled from the invading German Army with their pitiful bundles of belongings and frightened children in tow. Traumatized and bewildered, they were met by women volunteers who had set up emergency canteens on the concourse. There were British travellers too, who had found themselves stranded in Europe and further afield when war broke out, and were only now straggling home.

Departures were relatively few. Thousands of soldiers had already passed through Victoria on their way to France and Flanders. Weighed down by kitbags and buoyed up by patriotic songs, they had exchanged farewells with families and sweethearts before boarding their trains. One traveller, aware that many who said their goodbyes would never see each other again, called Victoria the ‘Palace of Tears’. Many more would follow. While the soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force, made up of the regular army and reservists, were already mired in the thick of battle on the Western Front, hundreds of thousands more men had since enlisted in response to the ‘call to arms’ declared by the new Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener. So far, at least, the casualties that had already begun to stream back from the first battles had been arriving at London stations under cover of night. Many, indeed, had never arrived back at all since the army’s medical services had been so overwhelmed by the sheer scale and severity of injuries with which they were dealing that thousands had perished before they could be treated.

Yet for all the fearful arrivals and sorrowful departures the atmosphere at Victoria Station that morning was predominantly cheerful – especially among the party of women waiting to board their train for France. For them one war had ended as another had begun.

JUST AS POLITICIANS of all colours had buried their differences to fight the common enemy on the outbreak of war, so a truce had been declared between women and men. After years of escalating militancy in the battle for votes for women, the leaders of the suffragists and suffragettes had put aside their demands immediately war began. Millicent Fawcett, president of the non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), had led the way by calling on her supporters to offer their services to their country within days of war being declared. ‘Women, your country needs you,’ she exhorted her members, even before Kitchener’s iconic poster made the same appeal to men. Emmeline Pankhurst, the steely matriarch of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), had followed her example a few days later, urging her militant suffragettes to suspend all activism and divert their energies and organizational skills into supporting the war effort. In return the government had announced an amnesty and released all suffragettes from prison – some several hundred women – within a week of declaring war.

Although some stalwarts of the women’s movement had joined pacifist campaigns, most women threw themselves into the new cause in a rush of patriotic fervour. One group of suffragettes had already launched the Women’s Emergency Corps to recruit women into jobs left vacant by men who were now enlisting. Women had flocked to its headquarters to sign up as drivers and motorcycle despatch riders or to run soup kitchens and refugee shelters. Aristocratic women and society ladies, until recently some of the loudest voices demanding the vote, were now offering their grand townhouses as convalescent hospitals for the wounded and raising funds to send medical units to France. And women everywhere, whether they identified themselves as suffragists or not, were signing up to play their part as volunteers at home and overseas.

Waiting to board their train at Victoria that morning, Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray had been among the first to recognize the unique opportunity that war presented to women. They knew that as well as posing a terrifying threat to the nation, war with Germany offered women a once-in-a-lifetime chance. Both qualified doctors, they were no longer in the first flush of youth. Louisa, forty-one, was a surgeon and Flora, four years older, a physician and anaesthetist. Yet despite more than ten years’ experience apiece, neither had enjoyed a significant spell of work in a major general hospital. Since hospital appointment boards were almost entirely controlled by men, women doctors were effectively excluded from training or working in mainstream hospitals or attaining high-status medical positions. Women were likewise barred from becoming army doctors regardless of the current pressing need. Although their medical qualifications were exactly equivalent to their male colleagues, Flora and Louisa had been restricted to treating women and children. Through necessity as much as desire, therefore, they worked in hospitals run by women for the treatment of women and children alone.

War had changed everything. Despite their complete lack of experience in treating men, or dealing with war injuries, the two women had decided to set up their own emergency hospital to treat wounded soldiers plucked from the battlefields in France. Gathering together a team of young recruits, including three more women doctors, eight nurses, three women orderlies and four male helpers, they were bound for Paris. It was a gamble. They were not only heading for unknown dangers in a war zone with eighteen young people under their command but their medical inexperience meant they were seriously unprepared for the challenges ahead. As committed to the women’s cause as they were to each other, Murray and Anderson saw the unfolding drama in France as their first chance to prove that women doctors were equal to men.

FOR LOUISA, ENTERING medicine had always seemed a foregone conclusion. Born in 1873, the eldest child of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman to qualify in Britain as a doctor, and James Skelton Anderson, a Scottish shipping owner from a family of medics, Louisa had grown up in a world suffused by medicine. Although she had been looked after by a nanny for much of her childhood, Louisa had vivid memories of riding in her mother’s carriage – holding out her hand to catch raindrops – when her mother made her doctor’s rounds from their house in London’s West End. On occasions she had even accompanied her mother to the New Hospital for Women, which her mother had founded in a poor part of Marylebone, where Louisa had romped on the beds. A younger sister had died from meningitis when Louisa was a toddler, then a brother, Alan, arrived when she was nearly four. A lively and imaginative child, Louisa was described by her mother as a ‘bright, skipping little creature, full of character and intelligence’.

Growing up with all the comforts of middle-class Victorian life, Louisa had enjoyed an idyllic childhood. While their parents worked long hours in London, Louisa and Alan ran wild in the sprawling grounds of their family home near the seaside town of Aldeburgh in Suffolk, albeit with Nanny keeping a close eye on the pair. In summer they bathed in the sea and sailed paper boats in the rock pools and in winter they skated on frozen ponds. From the age of eight Louisa wrote fond letters to her parents, nicknamed ‘Moodle’ and ‘Poodle’, relating tales of derring-do and make-believe while lamenting how much she missed them. The carefree childhood nurtured a rebellious streak so that ‘Louie’, as she was known, became quietly determined to get her own way in stubborn opposition to her mother, who fussed and worried over her children’s health.

After being tutored at home and briefly attending a girls’ day school in London, Louisa had been sent to a girls’ boarding school, St Leonard’s in St Andrews on the east coast of Scotland, at fourteen. One of the first public schools for girls, St Leonard’s modelled itself on the country’s top boys’ schools. Although the girls wore demure long skirts and long-sleeved blouses, they learned Greek, Latin, French and mathematics, and played cricket and tennis, just as their brothers might do at Eton or Rugby. Clever and bookish with a pretty face, pale complexion and long auburn hair, Louisa made friends easily and chafed at her mother’s fretting. ‘I must really expostulate against these sudden outbursts of excitement,’ she replied pompously when her mother feared she was ill. At first Louisa had been drawn to the arts: she edited the school magazine and took lead roles in school plays. Yet despite her displays of independence, by the age of seventeen she had decided to follow in her mother’s footsteps and embark on a career in medicine. This, even for the daughter of Britain’s most famous medical woman, was no small feat.

LOUISA’S MOTHER, ELIZABETH Garrett Anderson, had succeeded in becoming the first woman qualified in Britain to join the Medical

Register through a combination of iron will and stealth. In the mid-1800s, when Elizabeth was growing up, the daughters of middle-class families were raised with one ambition: to marry well. Since women were regarded as physically, intellectually and emotionally inferior to men, a serious education was seen as not only unnecessary but decidedly unfeminine. Most girls from well-to-do families were allowed only rudimentary tuition at home, followed by a few years at boarding school if they were lucky, to prepare them for married life. If they remained single over thirty, women were written off as ‘old maids’ and regarded as a financial burden on their fathers or brothers. The only routes to paid employment for middle-class women were becoming a governess or a lady’s companion – both widely despised as scarcely above the rank of a servant. It was understandable perhaps, as Louisa would remark when writing her mother’s biography, that Florence Nightingale ‘longed to die’ before she reached thirty.

Louisa was well aware of the obstacles her mother had battled. Born in 1836 into the prosperous Garrett family in Suffolk, Elizabeth had enjoyed just two years of formal education at a girls’ school in London from the age of thirteen. Condemned to remain at home until marriage, she had become bored and frustrated. So in her early twenties she fixed on the idea of becoming a doctor after meeting Elizabeth Blackwell, an Englishwoman brought up in America who had obtained a medical degree in 1849 at Geneva Medical College in the state of New York. When she returned briefly to England in 1858, Blackwell had become the first woman to enter her name on the newly established UK Medical Register. In a pattern that would become wearily familiar to women who dared to follow in her footsteps, this door was immediately closed as the General Medical Council (GMC) ruled that doctors who qualified overseas were ineligible for the register. When Elizabeth Garrett announced her ambition, her mother shut herself in her room crying. Her father, initially repulsed by the idea, became one of her strongest allies.

Over the next six years Elizabeth had battled every possible medical organization and educational institution in her mission to achieve her aim. Initially she trained as a nurse for six months at London’s Middlesex Hospital, where she persuaded the hospital apothecary to accept her as a pupil and even attended medical lectures until she angered the male students by answering a question nobody else could answer, at which point she was barred from future classes. One by one, every medical school and university in England and Scotland refused to admit her. But after completing her five-year apothecary apprenticeship, in 1865 she passed the examination of the Society of Apothecaries and in that way added her name to the Medical Register, thus becoming the first woman qualified in Britain to do so. Needless to say, the society amended its rules to prevent other women following her example.

Having qualified to practise as a doctor in Great Britain, Elizabeth had also obtained a medical degree in Paris – the first woman to do this – then slowly built up a viable practice in London. She even managed to join her local branch of the British Medical Association (BMA), the doctors’ professional organization, in 1873. Two years later shockwaves ran through the BMA’s annual conference when delegates realized to their horror that one of their members was wearing a crinoline and – in typical form – barred women from future membership. Elizabeth would remain the only female member of the BMA for the next nineteen years.

When Elizabeth had married Louisa’s father, James Skelton Anderson, a partner in the Orient Steamship Line, friends assumed she would give up her career. Far from surrendering her independence, Elizabeth not only continued her private practice but opened ten beds above the dispensary she had founded in Marylebone, creating the New Hospital for Women, to treat poor women in the district as well as providing clinical experience for other would-be female doctors. Yet since every door that Elizabeth had levered open had been just as quickly slammed shut by the male medical establishment, other women who aspired to study medicine had been barred from following her – despite determined efforts.

Seven women who had initially been permitted to enrol as medical students at Edinburgh University in 1869 were pelted with mud and bombarded with sexual abuse by male students when they arrived for an anatomy exam the following year. The attack may well have been incited by some of the university’s professors. A legal ruling then declared that the women should never have been admitted to the university in the first place and they were therefore refused their degrees. Some women, meanwhile, obtained medical degrees at universities on the Continent which were gradually opening their doors to female students, though this did not permit them to practise in Britain. Refusing to be defeated, one of the Edinburgh women, Sophia Jex-Blake, founded a medical school exclusively for women, the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW), in 1874. Despite personal differences, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson joined the teaching staff, which was otherwise entirely male. Still none of the nineteen medical examining bodies would accredit the school for teaching. A debate at the GMC the following year on the ‘special difficulties’ of allowing women to become doctors raised concerns about the smaller size of the female brain and the indelicacy of allowing male and female students to mix in the dissecting room.

Hostility to the idea of women becoming doctors intensified during the 1870s. One prominent doctor declared that he would rather follow his only daughter to the grave than allow her to study medicine. The British Medical Journal feared the ‘Temple of Medicine’ was ‘besieged by fair invaders’ while The Lancet warned of a potential ‘invasion of Amazons’. Finally the barriers were breached when Parliament passed the Medical Act of 1876 which enabled – though it did not compel – universities to admit women. That same year the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland agreed to recognize the LSMW and examine its students, providing them with a route to qualify for the Medical Register. A year later the LSMW struck a deal with the cash-strapped Royal Free Hospital to provide its students with clinical experience on the wards in return for handsome fees. Soon after, the school was incorporated as a college of the University of London. Other British universities slowly followed suit in admitting women as medical students, although Oxford and Cambridge would continue to bar women from studying medicine even in 1914.

The battle for women’s entry into medicine had been won. By the time Louisa Garrett Anderson set her sights on becoming a doctor in 1890, women were theoretically permitted to study medicine and qualify to practise – albeit chiefly through the LSMW. Some one hundred women doctors had added their names to the Medical Register by 1891. Obtaining postgraduate training and hospital experience was another matter. The route for men who wished to climb the medical career ladder was generally smooth and straightforward. After training at a reputable medical school they would normally be offered a junior post in the hospital attached to that school and – given the right connections and patronage – progress to a senior post in a specialty such as surgery or gynaecology. Hospital jobs were honorary and unpaid – hospitals were charities which treated only the poor while wealthier patients were attended at home or in private nursing homes – but they usually led to lucrative private practice in the chosen field. With no access to these male networks this route was denied to women.

None of the major medical schools accepted women students and the royal medical colleges in London and Edinburgh barred women from taking the specialist examinations required to progress up the surgical and medical ladders. Apart from at the Royal Free and one or two hospitals elsewhere, women were simply never considered for junior hospital posts by the all-male appointment boards. Effectively blocked from working in surgical or medical specialties, and likewise prevented from treating men, women were unable to take the first step on the career path leading to prominent hospital positions and successful private careers. Women doctors therefore had little option but to take low-paid and low-status jobs as medical officers in schools, prisons and asylums, or head overseas for jobs men did not want in medical missions – about a third of LSMW graduates went abroad – or else work in hospitals set up and run by women to treat women and children. Committing herself to medicine at the age of seventeen, Louisa therefore knew that the obstacles would be considerable and the opportunities few.

LEAVING ST LEONARD’S at eighteen, Louisa had enjoyed a holiday in Paris with her mother and brother then stayed on alone with a French family to brush up her French. Her mother was still fretting about her daughter’s health, remarking: ‘She will turn into a sweet, delightful woman if she lives, but I should much like to see her stronger.’ Clearly more robust than her mother believed, Louisa survived her French leave and spent the next year at the women-only Bedford College in London studying the sciences in preparation for medical school. The following year, in autumn 1892, she enrolled at the LSMW, where her mother was now dean, along with thirty other women students. She worked hard, winning several prizes, to qualify as Bachelor of Medicine at the end of the five-year course and Bachelor of Surgery the following year. Now legally entitled to practise as a doctor, she faced the scramble for her first hospital job.

Since there was no point in applying to a major general hospital, Louisa took junior posts at two charitable hospitals in poor areas of south London in 1898 and 1899. She gained her MD in medicine from London University in 1900, aged twenty-seven. Already she had determined on becoming a surgeon. Her mother had never enjoyed operating, Louisa would later say, but the young Louisa was inspired by another woman doctor, Mary Scharlieb, who had worked in India. Watching her perform complex abdominal surgery at the New Hospital, Louisa was awed at seeing ‘her slender hands seeming to go everywhere with marvellous speed’. The following year, when the Royal Free designated two of its six junior doctor posts for women, Louisa was appointed house surgeon there, becoming one of the first women to obtain a junior post in a general hospital albeit still only on the women’s wards and for just six months.

Eager for wider clinical experience she was forced to look overseas. Earlier in 1901 she had spent a few weeks with a friend in Paris attending anatomy lectures and even assisted at an operation – ‘both of us dressed up in Frenchman’s operating pinafores’, she told her mother. Then in December she and another friend sailed for the United States to attend lectures at two of America’s most prestigious medical schools.

Arriving in Baltimore, Louisa enrolled as a postgraduate student at the Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Medicine, which admitted women students on the same basis as men. Though she found Baltimore a ‘sleepy’ town, she was impressed by the school’s professor of medicine, Dr William Osler, who emphasized the importance of listening to patients – a novel concept – in forming a diagnosis. It was a practice Louisa would take pains to follow. Moving on to Chicago, she was shocked at the ‘bustling and dirty’ city with its seventeen-storey ‘houses’, but the clinical lectures of Dr Nicholas Senn, professor of surgery at Rush Medical College, made it all worthwhile.

Crammed into the lecture theatre with up to 500 other students, Louisa was transfixed as Senn exhibited some thirty patients in turn, then – after downing a glass of milk and beaten eggs – performed five or six major operations and the same number of minor ones. Having served as a surgeon in Cuba in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, Senn was an expert in military surgery and wound management. It is possible he instilled an appetite in Louisa for war surgery too. Her American experience confirmed her ambition to become a surgeon yet she was no nearer a permanent hospital post. In London, Paris and Chicago she had watched operations on men, women and children, and even assisted at a few, but she lacked direct experience of performing operations herself.

RETURNING TO LONDON in 1902, as the Victorian era gave way to the twentieth century, Louisa’s prospects were not promising. Her brother Alan had followed their father into the family shipping firm after studying at Eton then Oxford. Getting married in 1902, Alan’s future livelihood and career path were assured. Still living in the family home in London, Louisa enjoyed a generous private income from her parents. Yet although her training and experience were equal to those of her male contemporaries, she had no chance of securing a post as a consultant surgeon in a major hospital to provide the professional status she craved. There were now more than 200 women doctors on the Medical Register but almost all of them worked in women-run hospitals or dispensaries treating only women and children. One enterprising female doctor ran two sanatoria which treated both men and women for TB and a handful of medical women had West End consulting rooms where they attracted society ladies who chose to be examined by a woman rather than a man. Such a preference was not only regarded as eccentric but was fiercely opposed by male consultants eager to protect their profitable gynaecological practices. Attitudes towards ‘lady doctors’ were as hardened as ever. Louisa therefore had no option but to take a post in a women-run hospital treating women and children.

Just as her mother retired to Suffolk, in 1902 Louisa joined the staff of the hospital her mother had founded, the New Hospital for Women, which had recently moved into larger premises in Euston Road. She would work there as a surgical assistant and later senior surgeon until the outbreak of war. With forty-two beds and a busy outpatients department to run, the fourteen medical staff were in constant demand. Working-class women from all over London flocked to the New Hospital to be treated by women doctors; many were seriously ill after waiting months or years for medical aid. One patient had been in pain for four years while her male doctor insisted to her husband that she was suffering ‘hysteria’ before undergoing a successful operation at the New Hospital. By 1913, the hospital had expanded to include a cancer ward, an isolation ward – for venereal disease – and an X-ray department. That year the staff treated nearly 900 in-patients, attended 300 women giving birth at home and saw more than 32,000 outpatients.

At the New Hospital Louisa was kept busy performing gynaecological operations as well as some general surgery. She approached her work with rigorous scientific method, judging from a research paper she published jointly with the hospital’s pathologist in 1908, which analysed 265 cases of cancer of the uterus over the previous twelve years. The paper, which included results from some of her own operations for hysterectomy, not only emphasized the importance of following up patients after their operations to assess which surgical method was most successful but stressed the need for surgeons to work closely with pathologists. Meanwhile, she set up consulting rooms in a house her father had bought her in Harley Street – London’s most popular medical address – in 1903. The family name drew some prominent patients; in 1910 she signed the death certificate of Florence Nightingale.

Yet despite the family connections, Louisa was completely blocked from advancing in surgery so long as men still held the keys to all the major London hospitals and specialist positions. While her mother’s generation – the pioneer women doctors – might be happy to accept their confinement to women-only hospitals, Louisa and her contemporaries – the second generation of medical women – were not.

IT WAS LITTLE wonder, given the injustice and discrimination she faced, that Louisa Garrett Anderson had been drawn to the battle for women’s rights. Here too she was following in family footsteps since her mother had supported women’s suffrage from its earliest days. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson had jointly presented a petition to Parliament demanding votes for women as far back as 1866. But it was Louisa’s aunt, her mother’s younger sister Millicent Garrett Fawcett, who had taken up the banner for women’s votes most forcefully. Aunt Millie had become founding president in 1897 of the NUWSS, which campaigned for the vote through democratic means. By the time she was thirty, in 1903, Louisa was active in several organizations affiliated to the NUWSS. But by 1907 she had become impatient with the suffragists’ moderate tactics, which had achieved nothing but lip service from the Liberal government. So she joined the newly formed and much more confrontational WSPU – the suffragettes – led by the formidable Emmeline Pankhurst and her charismatic daughter Christabel. Compared with the demure earnestness of the suffragists, the suffragettes provided a far more exciting and glamorous prospect. Hearing Christabel speak, one recruit declared ‘it thrilled me through and through’. Louisa made large donations to the WSPU and joined its protest rallies, speaking at several meetings and leading women medical graduates on one of its marches.

As the protests escalated, with mass arrests of women who chained themselves to railings and ambushed election rallies, Louisa applauded the WSPU’s policy of civil disobedience and even tried to persuade Aunt Millie to join forces. Exasperated at the slippery twists and turns of the Liberal Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, in 1908 Louisa urged her aunt to support the WSPU in ‘more militant action’. Despite two enormous NUWSS and WSPU demonstrations that summer, the government remained intransigent. ‘Surely we must do something,’ she told Aunt Millicent. ‘They [the WSPU] mean to protest at once & on a large scale & unless we can protest constitutionally & effectually I think it is the duty of everyone who is able to do it to join them.’ To do nothing, she insisted, is ‘really too feeble’. Her appeal was fruitless – Millicent Fawcett would become increasingly opposed to the WSPU’s uncompromising approach – but Louisa had more success with her mother. That summer Elizabeth Garrett Anderson joined the WSPU – a major coup for Mrs Pankhurst – and spoke at several rallies. A few months later Louisa was among the crowd when suffragettes attempted to invade the House of Commons and she later gave evidence in support of the action when Mrs Pankhurst was tried for incitement.

The following year, in October 1909, as suffragettes on hunger strike were being force-fed by prison doctors for the first time, Louisa hosted the inaugural meeting of the Women’s Tax Resistance League in her Harley Street house. Refusing to pay income tax on the basis that they were denied representation, its members included several women doctors. And a year later, when Asquith provoked fury by blocking a promised new bill, Louisa was ready to act on the WSPU’s motto of ‘Deeds not Words’.

After warning the New Hospital board that she might be arrested, on 18 November 1910 she joined her mother on the platform of a huge rally in Caxton Hall, central London, along with Mrs Pankhurst and other leading suffragettes. After Mrs Pankhurst spoke, the Garrett Andersons followed her out of the hall to lead 300 women in a march on the House of Commons. In Parliament Square they were met by ranks of police and hired hooligans who blocked their way. Although Mrs Pankhurst and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson were allowed to pass, other women were jostled and assaulted. ‘I nearly fainted,’ said one supporter, ‘and Louie Garrett Anderson succeeded in making them let me through.’ In the pitched battle which ensued, more than one hundred women were arrested and scores were injured and sexually molested. Louisa herself was arrested but released without charge. The day would become known as ‘Black Friday’. Undeterred by the increasing violence, two years later Louisa was prepared to take a crucial step further in support of the women’s cause.

On 4 March 1912 Louisa joined a mass protest of suffragettes who marched through London’s West End smashing windows with hammers and stones. They had been motivated by the jibes of a Liberal MP, Charles Henry Hobhouse, who proclaimed that if the suffrage campaign really enjoyed popular support then women would be breaking the law like the men who had agitated for the 1832 Reform Act. Louisa was arrested for throwing a stone through the window of a house in Knightsbridge and sentenced to six weeks’ hard labour in Holloway Prison. Pleading guilty, she said her action was a ‘political protest’ prompted by Hobhouse’s remark about the 1832 campaign and added: ‘We are fighting the same battle as was fought then, and if it is the only argument that the country can understand we are obliged to use it.’ It was a bold and dangerous step. As a doctor she was risking her reputation by engaging in militant – indeed criminal – activity. Seizing on her status as a high-profile figure, newspapers broadcast her conviction under headlines such as ‘Lady Doctor Sentenced’ – although one at least felt the need to point out that it was not her mother, who almost approached the status of a national treasure, who was in the dock. Aunt Millie was none too pleased. The Times report of Louisa’s sentence was juxtaposed with an article reporting Millicent Fawcett’s condemnation of the suffragettes’ actions.

Gamely resigning herself to a spell behind bars in the notorious Holloway Prison, Louisa smuggled out several letters to her mother written in pencil on tissue-thin paper. By now her mother had severed her links with the WSPU but Louisa told her she was ‘glad & proud’ of her actions because she believed that ‘this kind of fighting … is necessary to win our Cause’. Despite the hard beds, plain food and lack of freedom, she made light of her situation, likening the prison to ‘a badly kept hotel with cold monotonous food & bells that no one answers!’ In a demonstration of the stoicism that would stand her in good stead in years to come, she described her enforced break as ‘a complete holiday’.

Far from deterring her from future militancy, Louisa’s imprisonment reinforced her loyalty to the women’s cause as well as giving her a taste for being in the midst of the action. ‘This is the most wonderful experience I have ever had,’ she enthused and added, ‘it is enormous luck to be alive just now & in this thing, really in the centre of it’. The sight of desperately poor women in jail for petty theft and prostitution, some of them with babies, reduced her to tears and made her all the more determined to improve women’s lives. ‘I never knew so clearly before why I was a suffragist,’ she wrote. Through it all the camaraderie among the suffragette inmates maintained morale. While Mrs Pankhurst kept up spirits, the composer Ethel Smyth conducted the women in a rendition of the suffragette anthem by waving her toothbrush from her cell window.

One fellow prisoner described Louisa dancing a Highland fling with another inmate and organizing games of cricket with pieces of wood. ‘Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson is the leading spirit, assisted by Dr Ethel Smyth,’ she said. Another, who kept a secret diary, said of Louisa, ‘it amused me so much to see her running hard today playing … under the shadow of a high prison wall.’ Meanwhile, Louisa’s brother Alan used his business influence to persuade the Home Office to release his sister five days early on the understanding that her family would devote the time to encouraging her to moderate her rebellious ways. The Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, sanctioned her release before Easter, so she was home by the time her fellow prisoners began a hunger strike. Louisa protested at her special treatment, telling a suffragettes’ meeting two weeks later that due to her social standing ‘the Home Office found that I might like to spend Easter with my family’ while other prisoners had spent the holiday behind bars.

Although Louisa left the WSPU a few months later, along with others objecting to Mrs Pankhurst’s increasingly autocratic conduct, her prison sentence made her more radical rather than less. It was in this atmosphere of intense political agitation that Louisa had got to know Flora Murray.

BORN IN DUMFRIESSHIRE in the Scottish borders in 1869, Flora Murray was the daughter of a retired naval commander with a long Scottish heritage and a sizeable country estate. A prominent local family, the Murrays had lived at their home, Murraythwaite, for almost 500 years. Flora, the fourth of six children, had grown up in a grand mansion house amid lush gardens surrounded by farmland and woods. Yet her childhood was not without its strains. Her father, John Murray, the sixteenth Laird, had died when she was three, leaving her mother Grace to bring up her six children and manage the estate alone. Although there was income from tenant farmers and shares, there was little left for luxuries. Nonetheless Flora had enjoyed private tuition in Edinburgh and attended girls’ boarding schools in London and Germany. When home she rubbed shoulders with the local gentry at hunting events and county balls escorted by her eldest brother William, the seventeenth Laird.

Although she was four years older than Louisa, Flora had embarked on her medical career later. At twenty-one she signed up for six months’ training as a nurse at the London Hospital, Whitechapel, before deciding she wanted to become a doctor and enrolling at the LSMW in 1897, the year Louisa left, at the comparatively mature age of twenty-eight. Just over two years later, in January 1900, her second eldest brother Fergus, a captain in the Scottish Rifles, was killed in action in the Boer War, aged thirty-one. Despite being wounded in four places, Captain Murray had continued to command his troops before he finally expired. His death in battle may well have inspired Flora to serve in some military capacity. That same year she left the LSMW, perhaps to be closer to her grieving family, and finished her training at Durham University. She qualified in medicine and surgery in 1903 before gaining her MD in medicine in 1905.

Facing the usual brick wall confronting women doctors, Flora took a junior post at Crichton Royal Institution, a vast Victorian asylum near her family home, in charge of female patients. Moving to London in 1905, she had no choice but to follow the path of other women doctors in taking honorary posts in small hospitals for women and children. Flora worked as a house surgeon at Belgrave Hospital for Children in south London and assistant anaesthetist at Chelsea Hospital for Women. Taking a keen interest in children’s health and anaesthesia, she published an article in The Lancet in 1905 on the safest form of anaesthetic for infants and championed the idea of ‘health visitors’ who would offer advice on child welfare to poor mothers in their own homes.

Yet despite her personal ambitions and determination to improve healthcare, Flora was as stymied as any other woman doctor in pursuing her goals. With only a small income from private patients, possibly supplemented by an allowance from her family, she was not well off. ‘Her early life was a struggle against hard conditions and financial stress,’ Louisa would later say. The problems plainly rankled. Observing male colleagues of equal or lesser abilities rise effortlessly through the ranks, Flora grew increasingly angry. In an impassioned article in the New Statesman in 1913, she railed against the inequalities and discrimination. Women were denied entry to medical schools, blocked from postgraduate training and refused jobs in hospitals, she wrote. ‘Staff appointments are professional prizes. They are made by the council or governing body, generally consisting entirely of men, upon the advice of a medical staff composed entirely of men. They are usually given to men.’

Like Louisa, Flora had thrown herself into the battle for women’s rights, joining Mrs Fawcett’s NUWSS soon after arriving in London and later Mrs Pankhurst’s WSPU. Flora never engaged in overt militant activity or went to prison like Louisa, yet her involvement with the suffragettes was potentially far more dangerous. Not only did she speak at rallies and join marches, she organized first aid posts to treat women bloodied and battered in the clashes with police as well as tending Mrs Pankhurst and other suffragettes when they were released from prison, emaciated from hunger strikes, at a nursing home she helped to run near Notting Hill Gate in west London. Flora was regarded as ‘honorary physician’ to the WSPU and, according to Christabel Pankhurst, ‘devoted herself to the medical care of Mother and of all our many prisoners’.

After the government sanctioned force-feeding of hunger-striking suffragettes in 1909, Flora had become one of the most vociferous opponents of the practice. While most of the medical profession maintained that forcible feeding was safe, she rallied sympathetic doctors who protested that it was both dangerous and inhumane. Within weeks she had organized a petition to Asquith signed by 116 doctors. She continued to campaign against force-feeding by writing pamphlets and articles which outlined the medical dangers in graphic detail. From her experience treating Mrs Pankhurst and other force-fed suffragettes, Flora declared that ‘teeth may have been broken or loosened, the body is black and blue, the marks of nails are visible on the hands and arms of the victim’. In the most serious cases a woman had contracted pneumonia after food entered her lungs and a man had become insane.

Many suffragettes would later write with fond affection of Flora Murray’s care. Kitty Marion, an actress who was force-fed 232 times, said that ‘it was a joy and comfort to be received and cared for by our own splendid Dr. Flora Murray’ at Flora’s nursing home. Frances Bartlett, a WSPU organizer who worked at the nursing home, said: ‘All the women who were being forcibly fed were brought to that house. Some were brought there on stretchers, and looked after until they were well again.’

As the government grew increasingly alarmed at the prospect of a suffragette dying and being hailed a martyr, legislation was introduced in 1913 which allowed prisoners to be released for short periods on licence to recover from their hunger strikes before being rearrested to continue their sentences. Flora was quick to condemn the law, dubbed the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, as ‘brutalising and degrading’. Writing in The Suffragette newspaper, she described how Mrs Pankhurst and others were released from prison in a precarious state of health then rearrested before they had fully recovered only to return a few days later ‘on a stretcher, half-killed’. She declared: ‘The true meaning of it all is murder – murder by Act of Parliament.’ By this point, in 1913, Flora was looking after Mrs Pankhurst and other activists on an almost full-time basis. She frequently gave evidence in court attesting to defendants’ medical conditions. When released on licence many prisoners were discharged into her care and when their licences expired the warrants for their rearrest were often issued to her. In one series of photographs Flora is pictured with Catherine Pine, a redoubtable nurse who cared for many suffragettes, accompanying Mrs Pankhurst as she was apprehended by a detective before she sank fainting into Nurse Pine’s arms. Another time Mrs Pankhurst was returning from Paris with Murray and Pine when two detectives boarded the train at Dover and arrested her. While Mrs Pankhurst and other activists were being shadowed constantly by officers from Scotland Yard, it is clear that by 1913 Murray was herself under surveillance by detectives who suspected her of aiding and abetting her patients in outwitting the police and committing further outrages.

By this stage the WSPU campaign had reached unprecedented levels of violence as private property was set on fire, chemicals were poured into post boxes and telegraph wires were cut. A cottage belonging to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, was badly damaged by explosives and a tea room in London’s Regent’s Park burned to the ground. It was ‘guerrilla warfare’, said Mrs Pankhurst. Meanwhile, the suffragettes had become adept at evading rearrest under their Cat and Mouse licences by adopting elaborate disguises and affecting ingenious getaways. One suffragette nursing home, nicknamed ‘Mouse Castle’, was besieged by detectives day and night, though this did not stop Annie Kenney, a WSPU organizer who was one of Flora’s patients, from escaping over a garden wall by dint of a rope ladder and going on the run.

Flora was plainly complicit in some of these great escapes. Kitty Marion described how a friend dressed as her ‘double’ and left Mouse Castle in a taxi to trick detectives into following her while Kitty boldly walked out minutes later and boarded a bus, having been dosed by Murray with strychnine to ‘brace me up’. At times Flora’s own house was watched by detectives and she was followed as she went about her duties. When Edwy Clayton, a chemist who supported the WSPU, was tried in 1914 for conspiracy to bomb government buildings and other targets, a detective giving evidence said he had followed Clayton to Murray’s house and kept watch for three days before Flora told police Clayton had left and the surveillance was lifted.

Colluding with the suffragettes’ increasingly violent tactics, Flora Murray was making powerful enemies in the Home Office and other authorities. By the summer of 1914 she found herself under attack within the medical profession too. Murray and a fellow physician, Frank Moxon, had accused doctors at Holloway of drugging prisoners with bromide to make them more docile for force-feeding and published results of laboratory tests on three women to back their claims. In July the Holloway doctors sued both Murray and Moxon for libel.

MIXING IN MEDICAL circles sympathetic to the suffragettes, Flora and Louisa had become friends. Before long this connection had deepened. Tall and slim with red hair, sharply defined features and a boyish figure – one friend described her as ‘flat-chested’ and ‘hipless’ – Murray, known as ‘Flo’ to her friends, was a taciturn but forceful personality who kept calm under pressure. Acquaintances regarded her as ‘cool and reserved’ – one described her as ‘very Scottish & harsh’ – but friends thought her ‘tender and gentle’ with a pervading aura of composure. One colleague said ‘even the fractious baby in a children’s hospital ceased its crying when Dr Murray spoke’. Flora found common cause with the more demonstrative, more impulsive, more gregarious Louisa. Both ambitious to succeed in medicine, they raised funds to open a tiny hospital for children in two terraced cottages in Harrow Road, a desperately poor area of west London, in 1912. Proudly brandishing their political affiliations, they adopted the WSPU slogan ‘Deeds not Words’ as the hospital’s motto.

Since hospitals for children were still a rarity, the Harrow Road outpatients department had been quickly overwhelmed by demand from needy families all over London. As many as one hundred children crowded the clinic on a single afternoon and the hospital treated more than 7,000 patients in its first eighteen months. Raising funds from well-heeled friends, Louisa and Flora expanded into the neighbouring house and opened a ward with four beds and three cots in 1913. A female journalist, shown round by Louisa in the summer of 1914, was touched by the scene. She found the wards brightly decorated with red, blue and white bedspreads and liberally supplied with toys. Louisa had ended the tour by picking up ‘a stout and aggressive toy donkey’ which she introduced as ‘Bodkin’. Others were less impressed. The Hospital magazine, which took a dim view of women doctors, thought the building ‘wholly inappropriate’ for in-patients with its primitive bathroom and tiny operating room. At the centre of this clamour, Flora is pictured in a photograph calmly writing a prescription in a crowded clinic as a mother bounces her baby on her knee and a girl holds up two dolls to the camera.

Jointly running their little hospital, Anderson and Murray juggled the demands of their other medical posts as well as their suffragette activities. By this stage, they were not only partners in their medical work, they had become partners in their private lives too.

BY EARLY 1914, Flora and Louisa were living together at 60 Bedford Gardens, a semi-detached Victorian villa in Kensington which Louisa had bought the previous year. Handy for the children’s hospital and the suffragette nursing home, the house boasted four bedrooms, a library, wine cellars and a walled garden. They also jointly owned a weekend cottage they had built in the village of Penn in Buckinghamshire a few years earlier. Murray and Anderson were not unusual in setting up home together as two unmarried women in the early twentieth century. For many single professional women, sharing a house provided not only financial convenience but social independence. Styled ‘Boston marriages’ after two female characters in Henry James’s novel The Bostonians, these arrangements particularly suited medical women who valued the mutual support of working and living together in a hostile male environment. As many as 80 per cent of women doctors were unmarried in the early 1900s. Marriage and medicine ‘did not mix’, said one female doctor, who believed ‘a wedding-ring led to the graveyard of a medical woman’s ambitions’. For some women doctors – and a number of suffragettes – living together was part of a loving relationship as well as a convenient partnership. Unlike male homosexuality, lesbian relationships were not illegal, and were so little discussed they were rarely even suspected, so it was deemed perfectly respectable for two professional women to share a home without a hint of scandal. Flora and Louisa therefore made no attempt to keep their arrangement secret. Yet by 1914 it is clear they were effectively living as a married couple.

While she had been in prison Louisa had applied for Home Office permission for a visit from Flora – ostensibly ‘on business’ – a request that was refused. In later life Flora would refer to Louisa as ‘my loving comrade’ while Louisa would tell her sister-in-law ‘we hate being apart’. They wore identical diamond rings. One friend, a journalist and fellow suffragette named Evelyn Sharp, would later say she had enjoyed a close relationship with Louisa until Flora ‘came between us’ and ‘our friendship seemed broken’ just before the outbreak of war. Louisa and Evelyn had spent two summer holidays together in 1910 and 1911 at a cottage in the Scottish Highlands belonging to Louisa’s mother. Fondly remembering these trips, Evelyn described their ‘great times together climbing the easier mountains’. Writing to Evelyn after one of these holidays Louisa said their fortnight together had brought her ‘great happiness’, but she urged Evelyn not to hate the Penn cottage that she and Flora had recently bought and pledged that it ‘isn’t going to come between us’. Despite Louisa’s protestations, however, by early 1914 a rift had developed. Henry Nevinson, a veteran war correspondent and suffragette sympathizer who was devoted to Evelyn, though married, revealed that in January Evelyn had shown him ‘an appealing, passionately loving letter’ from Louisa arguing against Evelyn’s resolve not to meet. Evelyn, however, had told him the situation was hopeless owing to ‘Dr. F.M.’s bullying absorption of the other’. While Louisa seemed anxious to maintain her close friendship with Evelyn, Flora was apparently too possessive.

It is impossible to say whether Flora and Louisa enjoyed a sexual relationship – no letters between them have survived – but by August 1914, when they set off for France, they had certainly forged a lifelong loving bond. For both of them their partnership was inextricably bound up with their commitment to women’s rights and their determination to prove the worth of women doctors. The success of their medical mission to France was crucial in this cause.

THEY HAD ACTED quickly. During the summer of 1914 few people in Britain had anticipated war. Anxieties, if any, were focused closer to home on the threat of civil war in Ireland, the spate of strikes beginning to paralyse the country and the new round of vandalism being wreaked by suffragettes. Although by the end of July the tensions in the Balkans had made war in mainland Europe look increasingly likely, most people still believed this would not involve Britain. During the bank holiday weekend of 1–3 August, many Britons were enjoying seaside outings and countryside excursions under cloudless blue skies without a care in the world. As people returned to their homes that bank holiday Monday to news that Germany had declared war on France, reality began to sink in. The following day, 4 August, as Germany invaded Belgium and Britain’s ultimatum on Belgian neutrality ran out at 11 p.m., most people were still in shock. Waking up the next morning to news that Britain was at war, one prominent suffragette said that ‘the world in which we lived and dreamed and worked was shattered to bits’.

Yet within a week of Britain declaring war on Germany, as troops were being hastily mobilized for France and recruitment posters were pasted on walls, Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson had decided that they too would go to war. Just as male doctors in reserve units were being called up to serve in the army’s medical corps, so they resolved to dedicate their medical skills to the war effort. This was not only a chance to do their duty for their country, it was also a unique opportunity to gain vital surgical experience and prove that women doctors were every bit as good as men.

They did not waste time approaching the army or the British government. As suffragettes with records of political protest and criminal defiance, they were regarded in government circles effectively as public enemies. Besides, they knew there was no point in offering their services to the War Office. One fellow surgeon, the Scottish suffragist Elsie Inglis, had already volunteered her skills to army medical chiefs in Scotland and been smartly rebuffed by an official who told her: ‘My good lady, go home and sit still.’ Another woman doctor, Florence Stoney, who had set up the first X-ray departments at the Royal Free and the New Hospital for Women, had offered to take herself and her mobile X-ray unit to the front. She too had been spurned by the War Office. Instead, on 12 August 1914 – two days after the government set free all suffragette prisoners – Flora and Louisa had called at the French Embassy in London.

The two women had been received by one of the embassy secretaries in an ‘absolutely airless room’ which reeked of ‘stale cigar smoke’, Flora later wrote. In ‘somewhat rusty French’ they offered to organize a surgical unit for France. In retrospect, Flora would admit, the official had probably assumed they simply wanted to finance and equip a unit – in the manner of other women volunteers – rather than actually treat any wounded soldiers themselves. In France women doctors were no more welcome in the army than in Britain. Nevertheless, they were referred to the London headquarters of the French Red Cross who accepted their offer unhesitatingly and gave them less than two weeks to raise funds, recruit staff and marshal supplies.