Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

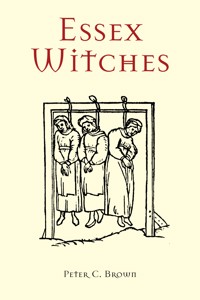

Medieval folk had long suspected that the Devil was carrying out his work on earth with the help of his minions. In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII declared this to be true, which resulted in witch-hunts across Europe that lasted for nearly 200 years. In 1645, England – and Essex in particular – was in the grip of witch fever. Between 1560 and 1680, 317 women and 23 men were tried for witchcraft in Essex alone, and over 100 were hanged. Essex Witches includes biographies of many of the local common folk who were tried in the courts for their beliefs and practice in herbal remedies and potions, and for causing the deaths of neighbours and even family members. These unfortunate citizens suffered the harshest penalties for their alleged sorcery and demonic ways, and those punishments are recorded here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 263

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

© Jasmine Hurst, Julie Chirila, Bernard Browne

CONTENTS

Title

Introduction

One England After the Tudors

Two What is Witchcraft?

Three Witches or Cunning Folk

Four Familiars and Witches’ Marks

Five Potions and Remedies, Spells and Incantations

Six The Acts upon Witchcraft

Seven The Assizes

Eight Mathew Hopkins – The Witch-finder General

Nine Confession and Torture

Ten The Accused

Eleven Witches and Halloween

Twelve Dispelling the Myth

Glossary

Credits

Bibliography

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

Medieval folk had long believed that the Devil was carrying out his evil work on earth with the help of his minions, and in 1484 Pope Innocent VIII declared this to be the truth in his papal bull Summis Desiderantes, which promoted the tracking down, torturing and executing of Satan worshippers. However, it was perhaps the reign of the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, James VI of Scotland and I of England that could be described as the ‘age of witchcraft’ in Great Britain. During the Tudor and Stuart period, Essex was an extremely religious county, and everyone – including the great, the wise and the learned – believed in witches. James VI of Scotland was a staunch Protestant who had narrowly escaped death in the winter of 1589 during strong winds and huge waves that severely buffeted his ship while on the North Sea. He believed, having been exposed to witch-hunting while in Denmark, that he was the target of a satanic conspiracy by sorcerers and witches who used black magic because of the way the ship behaved in the storm.

Upon his return to Scotland, James put into effect the practices carried out in Denmark and most of the Continent, namely the witch trials, and so began the wholesale persecution of witches.

As his paranoia about the Devil’s plot to kill him grew, James personally interrogated witches from the town of Trenton, including Geillis Duncane, Agnes Sampson of Paddington, Agnes Tompson of Edinburgh, James Fian (alias John Cunningham), Barbara Napier and Effie MacClayan, all of whom he believed to be Satan’s students. On his orders they were tortured to confess their part in plotting his demise. Following this he wrote a three-part working of his studies titled Daemonologie, which was published in 1597 and became something of a handbook for witch-hunters for identifying and destroying witches.

In 1604 he repealed the statute introduced by Elizabeth I, under which hanging was the punishment for those convicted of causing death by witchcraft, and replaced it with a more severe charter, that simply the practice of witchcraft was enough to cause a person to be hanged. Between 1603 and 1625 there were about twenty witchcraft trials a year in Scotland – nearly 450 in total. Half of the accused were found guilty and executed.

The legacy of James’s Daemonologie continued throughout the seventeenth century and led to the torture and execution of hundreds of women in a series of infamous witch trials. No one knows exactly how many died during this period, such as at the Pendle trial of 1612, or how many others were killed in cases that never came to court.

The fear of witches as the allies of Satan and his demons grew because of the hatred between the rival factions within the Church, when the Protestants and Catholics were literally at each other’s throats. The urge to eliminate evil spread very rapidly across Western Europe, and in France and Germany tens of thousands were sentenced to a terrible death. Witch-hunting was also widespread across Scotland and England, but most notably in Essex, which became the hub of witchcraft activity. Between 1560 and1680 there were over 700 people involved in cases of witchcraft in Essex, either as a suspect or a victim, and of these over 500 were prosecuted at the assizes, quarter sessions, or ecclesiastical courts. In 1645 alone, there were thirty-six witch trials in Essex.

Political and religious chaos reigned throughout the period of the English civil wars (1642–51) and it was against this background of religious upheaval, caused in part by the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, that the previously unheard-of Mathew Hopkins of Manningtree assumed the title of Witch-finder General in 1645. Witch-hunting throughout England was a judicial operation, but occasionally agitated villagers would take justice into their own hands, executing suspected witches in a vigilante style. However, after Hopkins took on the witch hunts, this rarely happened. His reputation spread far and wide and he had a profound impact on those around him. No one was safe from an accusation of witchcraft and marginalised women bore the brunt of it. Hopkins made a very lucrative living from it.

Note on the text: I have used the term ‘English civil wars’ in the plural in this book because although it is recognised as one war, between 1642 and 1651 there were, in fact, three separate wars. The 1642–46 and 1648–49 wars pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the supporters of the Long Parliament, and the conflict of 1649–51 saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II and those of the Rump Parliament.

ONE

ENGLAND AFTER THE TUDORS

The Stuart period of British history refers to the period 1603–1714 in England (in Scotland it began in 1371). Elizabeth I, the last of the Tudor monarchs, died on 24 March 1603. Having never married, she had no descendants and so her two kingdoms of England and Ireland were left to be ruled by her closest heir, the Scottish king James VI.

James’s greatest fear in life was a violent death. His childhood and adolescence were unhappy, abnormal and precarious; he had various guardians, whose treatment of him differed widely. Though his education was thorough, it was heavily weighted with strong Presbyterian and Calvinist political doctrine, and although he was highly intelligent and sensitive, he was also shallow and vain. In 1582, he had been kidnapped by Scottish nobles and only escaped the following year. This kept James’s fear for his life at the forefront of his mind.

A suitable queen was found for James in Anne of Denmark, and they were married by proxy in July in 1589. Arrangements were then made for the new princess to come to England, but as she set out, she was detained on the coast of Norway by a violent storm. James sailed to Upsala, and, after a winter in the north of the Continent, brought his bride to Scotland in the spring of 1590, but not without encountering more rough weather.

There were rumours that plots had been made against James over his alliance, and witches were accused of attempting to drown him by calling up a storm while he was at sea with his new wife. Several people, most notably Agnes Sampson, were convicted of using witchcraft to send storms against James’s ship. James became obsessed with the threat posed by witches and, inspired by his personal involvement, in 1597 he wrote the Daemonologie, a tract that opposed the practice of witchcraft.

King James I of England and VI of Scotland, by John De Critz the Elder.

The infamous Gunpowder Plot to blow up the House of Lords during the State Opening of England’s Parliament on 5 November 1605 further endorsed his fear and paranoia, and he signed an order that the captured conspirators should endure the minor tortures first and that the torturers should then move on to the more extreme measures to extract a confession. The public execution of those conspirators who were caught was a stern reminder of what would happen to anyone else foolish enough to involve themselves with treason.

The Stuart period was the beginning of a dramatic gap between the rich and the poor in England. At the top of society were members of the nobility, who owned huge amounts of land and commanded a lot of political power and influence because the government could not keep up with the rising costs of the civil wars, so had turned to them for support. The rents from royal lands could only be raised when the lease ended, which placed MPs in the position of refusing to raise money unless the king bowed to their demands.

Written by King James I and published in 1597, the original edition of Daemonologie is widely regarded as one of the most interesting and controversial religious writings in history.

The situation was further complicated by religion. The English Puritans were pleased when James I took the throne, for he had been brought up in Scotland by strict Protestants, men like themselves. They hoped that he would ‘purify’ the Church of England of its remaining Catholic elements, but no changes were made. Although he was a Protestant, James disagreed with many of their views, believing in the divine right of kings, and that God had chosen him to rule. Although he was willing to work with Parliament, he believed that ultimate authority rested with him.

THE ENGLISH HIERARCHY SYSTEM

Below the nobles of society were the lords of the manor (or gentry) and the rich merchants, who became steadily richer as trade and commerce became an increasingly important part of the English economy. These gentlemen owned large amounts of land and they were usually educated and had a family coat of arms. The monarchy relied on them to keep law and order, and they would sit as judges in the local courts. They would also control food prices and collect the taxes that were used to help the poor, although it was beneath their dignity to do any manual work. In the sixteenth century there was no National Health Service and no old age pension. Nor was there unemployment or child benefit. Instead, each town had almshouses and hospitals to look after the old and sick. Rich merchants often left money to almshouses in their wills.

Below the gentry were yeomen and craftsmen. Yeomen were the better-off villagers who owned their own pieces of land. Often able to read and write, they could also be as wealthy as gentlemen. They would pay labourers to work their farms, but would also work alongside them.

Then there were the tenant farmers, who owned no land of their own, but would lease strips of land from the rich to grow their own produce while earning a wage working for the lords or the yeomen. They were often illiterate and very poor, and life for them was very hard, with around 50 per cent of them living at subsistence level – having just enough food, clothes and shelter to survive.

Labourers were at the bottom end of the scale. They worked full time for landowners for very meagre wages and could afford to eat meat perhaps three or four times a week, the very poor perhaps only once a week. For at least part of the time they had to live on poor relief, which came after assessment by overseers or parish officers. In the villages, their homes were simple shacks made of clay, with wooden walls and a thatched roof. They could keep a cow or sheep on the common land, and their income would be supplemented by their wives, who would spin wool or churn butter as a way to pay rent and buy bread.

Farming in medieval England was very crude and hard, but it was critically important to a peasant family. The farmers had to carry out specific tasks throughout the year to ensure the best possible yield from the land they worked, which was invariably owned by the lord of the manor. There was plenty of land around the villages and the farmers grew crops needed to supply the towns in exchange for money they had to pay in rent of the land and taxes to the church, called a tithe, which was approximately ten per cent of what they earned. It was the tithe tax that was very unpopular, and it meant the difference between living and just about surviving after their dues were paid. What was left over could be kept, although the seeds for the following year’s crop had to be purchased.

Sheep, cattle, oxen and pigs were kept on many holdings, and these animals were invaluable to the farmer. In fact, they were more important to them and their day-to-day existence than their children; the loss of one animal would have been catastrophic. The animals were kept indoors at night because, if left outside, they would have just wandered off or been stolen. This made for a very unhygienic environment as there was no running water, toilets or a bath, but despite disease being common, it kept the animals safe.

The towns of the Stuart period were dirty, unsanitary and crowded, with the constant odour of rotting vegetables and effluent from the horses that drew carriages and carts. Water was usually obtained from wells, and some towns had conduits that brought in water from the countryside for the public to use. Houses were packed together in narrow lanes, and people were packed into the houses; ten to a room was not uncommon. There were no sewers and no drains, and offal and dirty water were thrown into the streets, providing perfect breeding places for black rats. The fleas that lived on the rats carried bubonic plague, which would quickly kill the people it infected. At night, carts would make their way through the streets and you would hear the mournful cry, ‘Bring out your dead.’ The plague was not over until 1665, when it was found that brown rats, whose host pests did not carry the disease, could drive the black rats from the towns.

The implementation of the Poor Law, which was the system for the provision of social security in operation in England and Wales from the sixteenth century, specifically defined the ‘poor’ and categorised them into three groups. These were ‘the impotent poor’, who could not work and provide for themselves, ‘the able-bodied poor’, those who were capable of labour but who could not find work, and ‘the vagrants’ – the beggars.

The Poor Law made provisions to offer relief and to provide materials to these people, of whom there were a significant number, and the resulting social improvements would have been a contributing factor in the decline of witch hunts as England, and indeed much of Europe, made the transition from early modern to modern times.

AGRICULTURE, FARMING LIFE AND WORK

Almost all farmers kept pigs, and most also owned a few cows and goats for milk and cheese, and sheep for their wool, grazing the animals on common land if permission was granted by the lord of the manor. Chickens were also kept for their eggs, and when the livestock came to the end of its effective productive life – when the number of eggs declined and the quality of the milk or wool became poor – it was slaughtered, salted and stored. This was usually done in the autumn because during the winter months the family and the animals had to try to survive on whatever food could be saved through a non-growing season.

The farmers also grew crops on arable land for their own food, and a small amount extra to take and trade in the town markets. This enabled them to buy from craftsmen what they could not make themselves, such as boots, hats, pots and pans, and harnesses for the livestock they used to plough the land. Daily life on the farm was a hard grind, and routines were dictated by the weather and the seasons, influencing the amount of daylight available for farming work. A field rotation system was used for growing wheat, oats and rye for cereals and breads, and, when mixed with vegetables, a dish called ‘pottage’ – a staple diet of the poor. Barley was grown for making beer. The water in this time period was so unsafe that beer was a very common beverage drunk by nearly all – children included. Life expectancy during this period was forty years.

By springtime, most people were on restricted rations of a very monotonous diet. Early garden vegetables were considered a great treat, but a bad storm or lack of rain at the wrong time could seriously reduce the crops available. The vegetables that would have been grown included carrots, parsnips, onions, and beetroot (turnips were not widely used until around the 1750s).It was here that the farmer, his wife and older children had to be multi-skilled, and they relied heavily on sharing the work with neighbours and hired labour, especially at harvest and market time. Foods, both vegetable and animal, were available only at certain times of the year.

Potatoes had become available, but were not trusted by the farmers; this ‘new’ vegetable was considered to be downright evil and was believed to cause leprosy, narcosis and early death. It took nearly 200 years before it was widely accepted as a beneficial vegetable. Even in Europe potatoes were regarded with suspicion, distaste and fear. Generally considered to be unfit for human consumption, they were used only as animal fodder and sustenance for the starving. Tomatoes, too, were treated with suspicion by farmers. Despite having been introduced to England around the 1590s, they took a long time to be accepted into rural farming communities as they were believed to be poisonous (they belong to the nightshade family of plants).

The wife’s lot was no less than the farmer’s. She would bake bread, make pickles and conserves from preserve vegetables, brew beer, and if they were as wealthy as yeomen, keep bees for honey.

BELIEFS AND MODERN SCIENCE

The class system was thought by all people to have been formed by God and that he had given it his blessing. Parents also believed that the word of the Bible provided instructions for taking care of their children. Another widely held opinion was that if you were unmarried, you were living in sin, which is why girls were married off at a very young age. However, fear of the unknown, moral panic, and belief in magic created many superstitions, many of which are still used today. For example, saying, ‘God bless you’ after someone sneezed derived from people’s belief that the Devil could enter your body when you sneezed, and that those words warded it off. A black cat crossing your path is thought to be unlucky because of the belief of their association with witches. Walking under a ladder is also considered unlucky; in the sixteenth century it reminded people of the gallows and executions. Breaking a mirror would bring bad luck for seven years because mirrors were considered to be tools of the Gods. Subsequently, ideas of witchcraft as heresy found a very receptive audience who believed that certain people, such as shamans, medicine men and women, sorcerers and witches, could intervene with the forces that controlled the world, and that these people could use magic to make things happen, controlling both the good and the bad in their lives. Scientists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries endeavoured to show that the world, and, indeed, the universe, were governed by discernable laws, but this would have little impact on the everyday lives or thoughts of the British and European masses.

Advances in biology and medical theory also did little to sway the prevailing belief. Bloodletting using leeches was the long-standing practice of trying to return the balance of the fluids to equilibrium, thus warding off illness, and remained so despite new and compelling theories about the body’s construct. Given the widespread illiteracy and ignorance in society, it was an unshakable set of beliefs and rituals that gave believers a sense of control over things that were seemingly uncontrollable.

TWO

WHAT IS WITCHCRAFT?

It is beyond the scope of this book to begin with the archaeological discoveries that have confirmed that the origins of our belief system can be traced back to the Palaeolithic peoples who worshipped a Hunter God and a Fertility Goddess.

What we refer to here as witchcraft dates back to the ancient Celts and Druids, although ever since humans started banding together in groups there have been practices of casting spells in order to harness occult forces; this was originally a nature-based belief wherein people gave reverence to the elements for the animals and vegetables they ate.

The Celts were a force in Britain by 480 BC, and occupied lands stretching from the British Isles to Galatia (modern-day Turkey), controlling most of Central Europe. By 700 BC they had forged themselves into parts of northern Spain. They were a deeply polytheistic people for whom superstitious belief was a way of life, and this belief was gleaned from their surroundings and stories that were passed from generation to generation.

They worshipped both gods and goddesses; their religion was pantheistic, meaning they worshipped many aspects of the ‘One Creative Life Source’ and honoured the presence of the ‘Divine Creator’ in all of nature. Like many tribes the world over, they believed in reincarnation. Their priests, judges, teachers, astrologers and healers were known as Druids, and were held in very high command by political leaders because of their power and influence. It took twenty years of intense study to become a Druid. These were the peacemakers, who were able to pass from one warring tribe to another unharmed, and remained in power three centuries after the defeat of the Celts at the hands of the Romans, which had conquered the south-east of England in around AD 43.

The religious beliefs and practices of the Celts grew into what later became known as Paganism, which is a blanket term typically referring to religious traditions that are polytheistic or indigenous. The word ‘Pagan’ is derived from the Latin word ‘Paganus’, which encompassed ‘country dweller, villager, and rustic’. Paganistic beliefs, blended over the centuries with those of other Indo-European-descended groups, spawned practices such as concocting potions and ointments, casting spells, and performing works of magic. Collectively, these practices became known as witchcraft, performed by a witch. This term comes from the Celtic word ‘Wicca’, from the Anglo-Saxon word meaning ‘to twist or bend’, which is derived from the word ‘Wicce’, which means ‘wise’, and describes somebody who is believed to have received supernatural powers. The craft has been defined in historical, religious, and mythological contexts as the use of alleged supernatural or magical powers (spells) applied to practices that people believed influenced the mind, body or property of others against their will. Practitioners were referred to as enchantresses, sorcerers, or witches – the pre-scientific judgement of the time.

Belief in witchcraft was (and may still be), in certain respects, the most logical or satisfactory explanation for misfortune or strange events. There were no experts in agriculture, and there were no veterinary surgeons, and whilst there were doctors, there were not enough of them. Moreover, they could not easily be afforded, so where medicine failed to heal, and it seemed that God did not hear prayers, partial hope for recovery could be sought by countering the magic of a witch.

Texts have also described witchcraft as a pact or covenant with the Devil in exchange for the power to do evil and harm others, but all such beliefs began from their association with things such as sickness, shortages of food, bad weather and failed crops. When times were bad, shamans, medicine people, witches and other kinds of magicians would cast spells and perform rituals to harness the power of the gods.

This produced mixed results; witches, who were primarily women, were originally seen as wise healers who could both nurture and destroy; this belief in their power, however, eventually led to fear, and this often forced witches to live as outcasts.

When Christianity became the prevailing religion in Europe, many of the ancient ‘pagan’ religions still survived, and these included magic-making practices. Subsequently, sorcery came to be associated with heresy and was viewed as evil, but these sorcerers could come in many guises: a professional healer, a midwife, a maker or purveyor of herbal remedies – even a person who was deemed to have made a profit while their neighbours languished in relative squalor. Poverty, misfortune and neighbourhood tensions were leading factors in fuelling accusations and could account for a large percentage of those accused of witchcraft. Sometimes they were condemned simply because they owned land that others wanted.

The Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of (the) Witches) was an infamous witch-hunting treatise used by both Catholics and Protestants. It was written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, inquisitors of the Catholic Church. It asserts that three elements are necessary for witchcraft: the evil-intentioned witch, the help of the Devil, and the permission of God. It outlines how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch.

Although witch persecutions were not really in effect until 1563, the use of witchcraft had been deemed as heresy by Pope Innocent VIII in 1484, and from then until around 1750, it is alleged that some 200,000 witches were tortured, burned and hanged across Western Europe.

The Malleus Maleficarum is a treatise on the prosecution of witches, written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer, a German Catholic clergyman.

THREE

WITCHES OR CUNNING FOLK

The English term ‘witch’ was not exclusively attached to one who consorted with the Devil to carry out his work. There are many misconceptions about witchcraft, but whether it is good (white) or bad (black), it is, on the whole, a religion which admires and gives utmost respect to Mother Nature, and the practitioners of either craft would not cast spells or perform rituals that went against her. ‘Evil’ or ‘black magic’ is traditionally referred to as the use of supernatural powers for evil and selfish purposes through association with the Devil. Its underlying ideology is that the knowledge and physical well-being of the practitioner are more important than other concerns, theological or ethical, and it is performed with the intention of harming another being, either as a means of building the practitioner’s power or as the goal itself.

In the new world of America, the most famous witch trial was conducted at Salem in Massachusetts in 1692. Witches there were considered to be only the ‘black’ (evil) type, and fear and hysteria led to trials and executions right across the province. In Britain, witches were no longer the subject of folklore or medieval myths – they were real, and a tangible representation of the Devil. They were held accountable for bad weather, failed crops and diseases of animals and people. In fact, almost anything that could be construed as just rotten luck was attributed to the diabolical acts of witches.

By contrast, ‘white magic’ was a form of ‘personal betterment’ magic, where the practitioner attuned himself or herself to the needs of human society and attempted to meet those needs by way of spells to watch over, heal, protect, bless, and to help themselves and those they supported. They intended to take over curses and hexes, reverse evil and protect against any kind of bad enchantment. White magic spells were the same thing as prayers, a vocalisation of what the witch needed, wanted or desired, and removed the middleman (God), focusing on the witch’s own personal power, their energy and the energy around them and their will to do good. These spells gave a better daily life, made wishes come true, were protective against the Evil Eye, restored friendships and were extremely powerful spells. Some of the healers and diviners historically accused of witchcraft considered themselves mediators between the mundane and spiritual worlds, roughly equivalent to shamans.

Folk magic was widely popular in Britain in the late medieval and early modern periods. While many individuals knew some charms and magic spells, the professionals – such as charmers, fortune tellers, astrologers and ‘cunning folk’ – were known to ‘possess a broader and deeper knowledge of such techniques and more experience in using them’ than the average person who dealt in magic, and it was believed that they embodied, or could work with, supernatural powers, which greatly increased the effectiveness of their business.

The Witchcraft Act of 1542 made no distinction between witches and cunning folk, and prescribed the death penalty for crimes such as using invocations and conjurations to locate treasure or to cast a love spell. The law was, however, repealed in 1547, and for the following few decades the magical practices of the cunning folk remained legal, despite opposition from certain religious authorities. In 1563, Parliament passed a law against ‘Conjurations, Enchantments and Witchcrafts’, and the death penalty was reserved for those who were believed to have conjured an evil spirit or murdered someone through magical means.

The ensuing witch-hunts largely ignored the cunning folk, and in the Essex records for the period 1560–1603, forty-two ‘cunning folk’ are mentioned, of which twenty-eight are male and fourteen are female. In answering to charges in connection with witchcraft, two of the women, Margery Skelton of Little Wakering in 1573 and Ursula Kempe of St Osyth in 1582, were found guilty and hanged. Four cunning men were also charged with witchcraft, none of whom were hanged, with two being acquitted. Throughout the early modern period the term ‘cunning folk’ was also used for practitioners of the craft who were ‘white’, ‘good’, or ‘unbinding’ witches, healers, seers, blessers, wizards, and sorcerers, although the most frequently used terms were ‘cunning men’ and ‘wise men’.

Davy Thurlowe, who was ‘strangely taken and greatly tormented,’ and whose back had twisted, was visited by Ursula Kempe, who employed a combination of counter-magic, after which he allegedly recovered from his torments. She took his hand and said, “‘A good childe howe art thou loden”, and so went thrise out of the doores, and euery time when shee came in shee tooke the childe by the hands, and saide, “A good childe howe art thou loden”.’ Kempe reassured Thurlow, firmly stating, ‘I warrant thee I, thy Childe shall doe well enough.’ Under examination Grace Thurlowe, Davy’s mother and a good friend of Ursula Kempe, told this story to Brian D’Arcy, shortly before she recounted how she and Kempe had fallen out.

In Britain, the ‘Cunnan’ – ‘cunning folk’ – were known by a variety of names in different regions, including ‘wise men’ and ‘wise women’, ‘pellars’, ‘wizards’, ‘dyn hysbys’, and sometimes ‘white witches’. They were most commonly employed to use their magic, charms and spells in order to combat malevolent witchcraft and the curses which these witches had allegedly placed upon people or their animals, or to locate criminals, missing persons or stolen property. They would also earn money fortune-telling, healing, and treasure hunting.

Some cunning folk obtained and used ‘Grimoires’ – textbooks of sorcery and magic – when they began to be printed in the English language. These tomes were displayed to impress their clients that they were all-knowledgeable, despite the fact that they may never have made any use of the magical rituals contained within them. Such books typically included instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms and divination, and how to summon or invoke supernatural entities such as angels, spirits and demons. The books themselves were said by some to have been imbued with magical powers.