18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

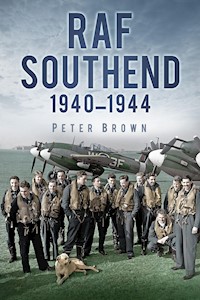

RAF Southend focuses on the airport's role in the Second World War, between October 1940 and August 1944, from when it became a fighter station in its own right, until it became an armament practice camp later in the war. It describes the manning and maintenance of the forward fighter station, often under attack, and follows the varying fortunes of the staff and personnel who were posted there, and the highs and lows of the events, occasionally tragic, that occurred on and around the aerodrome. It also gives in-depth details of the numerous defensive and offensive operations carried out by the various RAF fighter squadrons during their time based at Southend. Through interviews with ex-staff and eyewitnesses, and the meticulous cross-referencing of original material, this book makes will make a fascinating read for anyone with an interest in local, aviation or military history. Author Peter Brown is an established local historian, with many years of research in the Southend area.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

To my wife Karen for her devotion and patience

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword

Introduction

1. 1940

2. 1941

3. 1942

4. 1943

5. 1944

Epilogue

Glossary

Plate Section

Copyright

FOREWORD

War not only brings out the worst in us – it also encourages our better qualities. We never really know what is in us until tested; sometimes literally to destruction. Such was the Battle of Britain, in which RAF Southend helped to defend one of our most crucial sectors.

When I listened to Neville Chamberlain make his historic broadcast at 11 a.m. on 3 September 1939, I was a child of 10; perhaps a little precocious. We had all been expecting the worst. I received my own gas mask the previous year, read about Guernica, was warned that ‘the bomber would always get through’ and the need to create a refuge room. We had already floored out wet cellar as an air-raid shelter and made a pathetic attempt to camouflage the roof, due to our proximity to the aerodrome.

After the autumn and winter calm of the Phoney War while Hitler was getting his forces into position, the spring of 1940 brought a dramatic and disastrous change. First the loss of Norway, then the Blitzkrieg through the Low Countries and France, when Hitler made, in less than four weeks, conquests that had taken the Allies over four long years in the First World War.

We had not been wholly idle locally. There was a new searchlight in the field opposite our entrance, with a sandbag-encircled Lewis gun – the workings of which were explained to me. Just to our north at Canewdon, I used to cycle around some strange high wooden towers, subsequently joined by metal grid-like pylons. No one had yet told us about radar.

Our tranquil home was rapidly transformed as Southend Aerodrome became much closer to the enemy in flying time. Previously the aerodrome had been occupied by a few enthusiastic amateur pilots. There was also an Air Ferry with a twenty-minute flight across the Thames to Rochester. Suddenly we had become a front-line fighter station, the tip of the Hornchurch sword.

Our peace was shattered. Wing Commander Basil Embry, having just escaped from captivity in France, descended upon the aerodrome to knock it back into instant shape as a fighter station.

This included the requisitioning of our home as the Officers’ Mess. We were given forty-eight hours to get out (fortunately stretched to seven days) but my parents still regarded Basil Embry as a charming gentleman! We moved into our rather basic lodge, without electricity, which had just been vacated by a platoon of the Black Watch, with their Bren carriers parked outside.

The pilots and their back-up quickly moved in. Nissen and wooden army huts with ablutions were built for the support staff, the stable yard was covered with camouflage netting and defences quickly emerged nearby. A troop of four 25-pounders was emplaced at Gusted Hall, a mile to the west, with their command wires running through our ditches. Anti-glider scaffold tripods sprouted in our open field (still there), facing down the road to the aerodrome. We all felt a little more secure.

The aerodrome was also getting its act together. It included a flak tower along the Eastwoodbury Lane with Bofors, more guns on the airfield, small boxes with rockets trailing wires in the path of attacking planes, strategically placed pillboxes around the perimeter and horseshoe-shaped revetments to protect the Spitfires on the ground.

I spent my school holidays at our lodge, in a cupboard-size bedroom, but loved every moment of it. We were guests at The Lawn for their ‘Guests Nights’, which were positive feasts, as the mess could fly in from far and wide food beyond our meagre rations. Understandably parties got a bit noisy later, when we discreetly departed. Our large dinner gong was used for revolver practice; a pilot was placed in the flowerbed without socks and then up-ended to walk over the ceiling, and there were the usual mess high jinks, all of which my parents philosophically tolerated. When sitting in the garden of our lodge, we used to see the dispersal trucks go down to the airfield, full of pilots. Sadly they did not all return.

Recently we received a knock on the door from an ex-pilot who had come 12,000 miles from Australia to look at his old billet. He immediately identified his old bed place. He had just returned from Holland, where his Spitfire had crashed in 1943 and recently been excavated – and he was very proud of the souvenir he was given for it.

I was fortunate enough to enjoy my first flight when Squadron Leader Valance, the CO, took me up for a twenty-minute flip in an Air Speed Oxford (a general workhorse) and had the exhilaration of taking the stick.

Looking back, one began to tolerate the war almost as a way of life. We were never actually frightened and certainly not even hungry. I think the war rations were brilliantly done and actually we were healthier on the wartime food than today. It also gave me an excuse at boarding school to come home early, where we had been sleeping in the shelter, to an even more dangerous area of our home under the blast path of the V1s and V2s.

There was little crime, except for the black market. Its proceeds were chicken feed to the spoils legitimately earned in today’s financial markets. Generally we enjoyed a happier social climate, because everyone mucked in and helped each other. We also had a better social conscience and greater sense of discipline. National Service, which I thoroughly enjoyed, maintained this spirit through the 1950s.

Perhaps the heroism and self-sacrifice of the few had helped subconsciously to imbue us with a higher moral purpose.

David Keddie, 2012

INTRODUCTION

The Mass Evacuation of Southend

On 30 May 1940 the Southend Standard reported that the government had decided that in light of the fact that Holland and parts of Belgium and Northern France were in enemy occupation the following towns on the south-east coast were declared evacuation areas: Great Yarmouth, Lowestoft, Felixstowe, Harwich, Clacton, Frinton and Walton, Southend, Margate, Ramsgate, Broadstairs, Sandwich, Dover, Deal and Folkestone. Arrangements were made for those children whose parents wished them to be sent from these areas to safer districts in the Midlands and Wales.

On 6 June 1940 the Southend Standard reported that the first of Southend’s 8,500 children to be evacuated were on their way to their schools and later, at half-hourly intervals from 7 a.m., long heavily laden trains steamed out of the central LMS station on route to the Midlands.

Tiny tots struggled with rucksacks or suitcases and junior boys and girls, high school and technical students in long ‘crocodiles’ marched from the marshalling ground in the station yard to the barriers and then along the platform as each train drew in. A ceaseless procession of Westcliff motor buses carried the children from the schools to the station where members of the Education Department, nurses, first-aid party workers and helpers shepherded them from their allotted places. The whole evacuation was a triumph for local organisation and with the railway staff carrying out their share so smartly the trains were always ready to leave at the scheduled time. With the majority of the pupils and the whole of the teaching staff away, the schools were closed.

A public poster dated 30 June 1940 was displayed:

PLEASE CONSIDER THIS: If evacuation of this town is ordered it may not be possible for you to take your pet animals in the train. Animals will be painlessly destroyed by competent persons.

This poster not only caused much alarm and distress to the owners of animals but frightened hundreds, if not thousands of people out of the town with their pets.

On 17 October 1940 the Southend Standard reported that there was no ‘Intention of Re-Opening Southend’s Schools’. It was definitely stated at the meeting of Southend Town Council that there was no intention of bringing the evacuated schoolchildren back to the borough and no possibility that any schools would be opened at Southend for the education of the children still in the town. The Probation Office had been urged to address the problem of hundreds of children running around the streets in this town with no provision whatsoever for their education.

Vulnerable Targets

THE EKCO WORKS

In August 1939 there was the usual throng of thousands of holidaymakers visiting Southend for a walk along the 1¼-mile-long pier, delighting in the amusement arcades, sampling the many public houses along the seafront, visiting the Kursaal, enjoying ‘Old Leigh’ and its many cockle sheds or simply relaxing on the miles of beach. In another part of the town, EKCO was busy with last-minute preparations for the annual Radiolympia exhibition where the company had high hopes for the show, especially since they were planning to exhibit along with their radios, for the first time on any scale, their full range of television sets; they hoped that a good show would provide continuity of employment for the 3,000 or so people working at the site in Priory Crescent.

Alas, during the course of the Radiolympia show, with the dark clouds of war gathering, the government announced that due to the international situation television broadcasts were being suspended with immediate effect and ten days later war was declared. This not only drove away the visitors from Southend but meant that EKCO, almost overnight, voluntarily ceased domestic radio and television work and made its entire production capability available to the government, which accepted the offer with thanks. Thus, in short order the company found itself manufacturing military Type 19 tank radios.

At the same time, the site at Southend was prepared for war with surface air-raid shelters being built at various locations around the site, including one long slit trench down the length of the site, these complementing the deep shelters, which had already been built under the buildings erected in 1938 in accordance with the Air Raid Precautions Act (1938). Very quickly the roofs of all the buildings were painted in camouflage paint and security barriers erected at all the entrances to the site.

Even during the Radiolympia show plans were made to purchase a secure site known as Cowbridge House, deep in the countryside of north Wiltshire for the top-secret work on airborne radar and VHF communications for the RAF.

Not all production moved away from Southend, however; the large plastics moulding machinery could not be moved, nor was the lamp manufacturing unit moved, which covertly had been turned over to the military valve manufacturers, whose products included the very specialised ‘radar valves’. The plastics plant found itself working 24 hours a day making a wide variety of products, ranging from small Bakelite knobs to practice bombs.

At the time of Dunkirk (late May/early June 1940), with the Nazis having overrun Belgium and France (meaning that German aircraft could easily reach Southend which was only 100 miles away or less than half an hour flying time), the order was given by the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) to evacuate the whole of the works and disperse the work to safer sites away from the risk of being bombed.

Canewdon Chain Home Radar Station

Radar, which was to play such a vital part in Britain’s defence throughout the Second World War, but particularly during the Battle of Britain, had been developed in great secrecy during the mid-1930s at Canewdon, and was operational in 1938 as part of the country’s Chain Home Station System.

‘Chain Home’ was a network of coastal stations which at that time was the most advanced early warning system in the world. By 1939 its coverage stretched from the Isle of Wight to the Scottish border, and it gave Fighter Command advanced warning of enemy aircraft approaching the English coast, making it possible for fighter aircraft to be guided to intercept them.

The station at Canewdon was sited in an area of 18 acres on the edge of the village off Gardeners Lane, which was acquired by the Air Ministry and was the fourth such station to be built in Britain. It comprised both a receiving and transmission site; the receivers were set in earth-covered concrete bunkers a few hundred yards north of the 360ft-tall triangular transmitter masts. It was a vulnerable target for aerial attack, and in an area of less than 1 square mile, at least twenty-one pillboxes and machine-gun emplacements were constructed to defend against an airborne assault.

Southend Aerodrome

The airfield was established as a landing ground for the Royal Flying Corps during the First World War. It was decommissioned in 1919 and the site reverted to farmland. The site reopened in 1935 as a civil airport. At the outbreak of the Second World War it was again requisitioned by the Air Ministry, and by 1940 it had become an important advance fighter station within 11 Group for RAF Hornchurch. The airfield was still grass surfaced, and was equipped with a mixture of Bellman and Blister aircraft hangars.

It was not a particularly good area to defend from enemy paratroop attack and aerial bombing. ‘A’ Infantry Coy covered the area surrounding the airfield from New Road to Warner’s Bridge inclusive, and ‘B’ Infantry Coy covered from Avro Road exclusive to New Road inclusive.

The RAF Ground Defence Squadron consisted of LAA (Light Anti-Aircraft) Flight, AFV Flight, and PAC (Parachute and Cable) Detachment: the LAA troops were under the command of the anti-aircraft defence commander to engage enemy aircraft and in a secondary role to engage ground targets; the AFV Flight came under the direct command of the local defence commanders (LDCs) to engage and destroy enemy troops observed in the vicinity of the aerodrome; the PAC Detachment was prepared to fire rockets at enemy aircraft making low-level attacks on the aerodrome.

An RAF ‘backers-up’ squadron consisted of seven rifle flights and one Smith Gun Troop flight, which covered Warner’s Bridge exclusive to Avro Road inclusive. ‘F’ Flight (backers-up squadron) came under command of ‘A’ Infantry Coy on ‘Attack Alarm’, and ‘G’ Flight (Smith Gun Troop) came under the direct command of the LDC.

Adjacent troops were the Reserve Battalion: 2 Platoon ‘D’ Coy (HG) and 9 Platoon ‘B’ Coy (HG) Essex.

Anti-aircraft defences on the aerodrome consisted of one troop of Light Anti-Aircraft (Royal Artillery) manning four Bofors guns.

Off-station, there were more than seven heavy anti-aircraft gun batteries around the area: Fisherman’s Head, Ridgemarsh Farm and New Burwood on Foulness; and guns at Great Wakering and Sutton, Hawkwell and Rayleigh.

Troops under the command of the Reserve Battalion Area Command consisted of 1 Infantry Battalion, ‘A’ Battery of the Royal Artillery, and Rayleigh Coy, 1st Essex Battalion (HG).

Their Primary Defence Instructions on ‘Stand-to’ was the centre of the aerodrome. The intention was to defend it to the last, and if and when the aerodrome became in imminent danger of capture it would be destroyed and the troops would then be withdrawn under orders from the Reserve Battalion area commander.

The flying field had ten lines of pipes, five running east–west and five north–south. Each line had a number of intermittent lengths of pipes, each 60ft long, laid just below the surface and terminated at the surface at intervals of 85ft. The pipes were filled with blasting gelignite, and at each terminal point they were fixed with a short length of pipe set vertically in the ground and covered at ground level with a wooden tile painted white. A short length of waterproofed cortex with a detonator would make contact with the explosive and at the free end a paper clip was provided to connect the cortex lines. There were four igniting points (IPs), one at each corner of the flying field, and each IP had a wired electric detonator and primer, through which an electric current was introduced by exploders. The exploders would be carried into slit trenches about 100 yards away from the nearest pipe line. The cortex lines, which could not be used whilst the field was in use as it constituted an obstruction, would be run out and connected only on orders from higher authority if and when instructions were received to demolish the airfield.

Secondary to this were the areas in the south and west-north-west of the aerodrome, Rochford Hall and church, Doggets Farm, the west edge of the woods, and road junctions west and north-west of Rochford.

9 Platoon ‘B’ of Southend Coy (HG) Essex Regiment were posted to defend the east and south-east approaches to the aerodrome (and thus the EKCO Works) from Fleet Hall at Cuckoo Corner. At ‘Action Stations’ 33 Section would take up its position at Cuckoo Corner; 34 Section at New Hall; 35 Section at Temple Farm; and 36 Section at the rectory, with standing patrols in Temple Lane, the east of Sutton Road, and Sutton Hall.

Fifty pillboxes had also been constructed to protect the aerodrome, and three Picket Hamilton forts were sunk into the grass within the area of the landing strip. These were designed to be lowered to ground level while aircraft were operating, but to be raised when necessary by means of a hydraulic mechanism. The fort was manned by a crew of two with light machine guns.

The underground rooms of the Battle Headquarters, from which the defence of the airfield was coordinated, are still there today.

The two bituminous runways, 06/24 (1,605 × 37m) and 15/33 (1,131 × 27m), were laid using the method of soil stabilisation in 1955–56.

Acknowledgements

Station Logs and Squadron Operations Records Books consulted at the Public Record Office at Kew.

Bob Cossey (74 (F) Tiger Squadron Association)

Tom Dolezal (The Free Czechoslovak Air Force)

Geoff Faulkner (264 Squadron)

Aldon Ferguson (611 Squadron Association)

Major Jay S. Medves, MB, CD (Canadian Forces)

Captain Morgan Jones (402 Squadron, RCAF)

Valerie Cassbourn, Director, Histoire et Patrimoine

Bob North & Brian Rose (81 Squadron Association)

Derek Rowe (Southend Aircrew Association)

Henry Skinner (1312 ATC Squadron)

Jim Bell

Rob Bowater

Zdenek Hurt

David Keddie

Robert Ostrycharz

Chris Poole

Terry F. Smith

Robin McQueen

Special thanks to Dee Gordon for her advice and assistance.

1

1940

OCTOBER

28 OCTOBER

RAF Rochford, a satellite aerodrome of RAF Hornchurch in 11 Group, Fighter Command, was renamed as RAF Southend today, although Fighter Control remained with Hornchurch. (War Establishment No. WAR/FC/218 dated 28 October 1940.)

On formation of the Station Headquarters, Wing Commander B.E. Embry, DSO, AFC was posted to command (he had recently escaped capture after he was shot down in a Bristol Blenheim bomber over France). Flying Officer E. Dodd and Flying Officer A. Cairnie (attached from RAF Hornchurch) carried out administrative duties. Flight Lieutenant W.H.A. Monkton, MM and Pilot Officer E. Thursfield (attached from RAF Hornchurch) carried out duties of intelligence officer and ground defence officer respectively. Flying Officer R.L.G. Nobbs carried out medical duties on the station.

29 OCTOBER

264 Squadron arrived for night-flying duties; ‘A’ Flight flew in from RAF Martlesham Heath, and ‘B’ Flight from RAF Luton. They had suffered huge losses over the past months and their Boulton-Paul Defiants, which were no match for the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt Me 109s, were withdrawn from front-line operations.

Sergeant Alexander MacGregor (109895) of 19 Squadron, from RAF Duxford, made a forced landing in Spitfire P7379.

30 OCTOBER

Personnel from various units began to arrive to complete the establishment. These airmen were accommodated in requisitioned houses in the locality. The Station Headquarters offices and station stores were situated on the aerodrome.

31 OCTOBER

The Battle of Britain is officially regarded as having come to an end on this date but it actually proved to be one of the quietest days in four months. It was ironic that the aeroplane, an offensive weapon, should win its first and greatest battle as a defender.

Throughout the day from 07.30hrs until dusk, reconnaissance and scattered bombing raids were made over East Anglia, Kent, Sussex, South Wales, Hampshire and Lancashire. Bombs were dropped on the airfields of Bassingbourne, Martlesham and Poling with further targets in the Monmouth and Newport areas also being attacked.

Without victory, the Second World War would have taken a different course; with air supremacy the German Army could have landed and the odds are that it would have succeeded as the British Army had not yet recovered after the Dunkirk evacuation. Britain could not have been the base for either the Allied air offensive against Germany or the Normandy landings that led to the liberation of Europe in 1944–45. The Battle of Britain was, therefore, not just a local, territorial success over the south of England in the summer of 1940, but one of the most significant conflicts of the Second World War and the only major, self-contained and absolutely decisive air battle in history.

The battle was over. The war was just beginning.

NOVEMBER

1 NOVEMBER

Group Captain Murlis Green, DSO, MC arrived for several days on duty in connection with Night Operations.

This station was in the process of formation. Flight Lieutenant Monkton was posted in for intelligence duties, and Pilot Officer A.D. Rutherford-Jones reported on posting for equipment duties.

2 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officer William Moore (77947) returned to 264 Squadron after a visit to Messrs Boulton & Paul and Lucas in connection with the manufacture of power-operated gun turrets.

4 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officer Gillespie joined the 264 Squadron on posting from 614 Squadron.

5 NOVEMBER

At 16.15hrs, Pilot Officer František Hradil (81889), a Czechoslovakian pilot of 19 Squadron, was shot down in flames during combat over Canterbury by a Bf 109E of I/JG26. His Spitfire (P7545) crashed into the sea close to Southend Pier. His body was found on 7 November and he was buried on 12 November in Sutton Road Cemetery (Plot R, Grave 12160), Southend-on-Sea. He was 28 years old.

6 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officers Kenwyn Sutton (36282), Eric Barwell (77454), Richard Gaskell (42832) and Peter Bowen (42481) of 264 Squadron carried out night patrols and Pilot Officer Hughes carried out a dawn patrol the next morning.

7 NOVEMBER

In the late afternoon, while on convoy protection, a Me 110 was sighted and destroyed 10 miles north-east of Rochford by a flight from 603 Squadron (operating from RAF Turnhouse).

9 NOVEMBER

One section – Pilot Officers Hugh Percy (74688) and Desmond Kay (42006), and Sergeant Arnold Lauder (48822) – of 264 Squadron carried out patrols in the morning, and Sergeant Cyril Ellery (78747) arrived to join the squadron on posting from 150 Squadron.

10 NOVEMBER

Night patrols were carried out by Squadron Leader George Garvin (34237), Flying Officer Ian Stephenson (72010), Pilot Officers Gerald Hackwood (42217), Richard Stokes (42027), Terence Welsh (42033), Flight Sergeant Edward Thorn (46957) and Sergeant Endersby of 264 Squadron.

12 NOVEMBER

Flying Officer D. Edwards arrived for engineering duties, and Flying Officer (Acting Squadron Leader) Harold ‘Flash’ Pleasance (37914), DFC was posted here for operations duties.

Night patrols were carried out by Squadron Leader Garvin, Flight Lieutenant Smith, Flying Officer Stephenson, Pilot Officers Robert Young (NZ40197) and Welsh, Flight Sergeant Thorn and Sergeant Endersby of 264 Squadron. Pilot Officer James Melvill (74681) carried out two night patrols.

14 NOVEMBER

Flying Officer Edwards (Engineering) was granted the acting rank of flight lieutenant. Flight Lieutenant Ernest Campbell-Colquhoun (39301) left 264 Squadron on posting. Squadron Leader Garvin carried out a test of experimental exhausts. Night patrols were carried out by Pilot Officers Melvill and Young; one patrol was carried out by Flight Lieutenant Edward Smith (90093) and Sergeant Godfrey Smith (1223091), Flying Officer Stephenson, Pilot Officers Welsh, Hackwood and Kay, and Flight Sergeant Thorn with Sergeants Endersby and Lauder.

15 NOVEMBER

Squadron Leader A.T.D. Sanders was posted in for operations duties. Flying Officers K.L.S. Nobbs and R. Cargill were posted here for medical duties, and Acting Flight Lieutenant E. Dodd was posted here from RAF Hornchurch for duty as adjutant. Pilot Officer Stokes left 264 Squadron on posting.

At 18.30hrs, Flight Lieutenant Samuel Thomas (42029), and Pilot Officers William Knocker (74333) and Bowen of 264 Squadron took off for night patrols. Knocker’s aircraft, Defiant N1547, caught fire in mid-air and, after an unsuccessful attempt to land down wind before another attempt could be made, hit a tree and crashed on Rochford golf course, adjacent to the aerodrome. The wrecked aircraft burst into flames, but Knocker managed to crawl away quickly from his blazing cockpit whereupon he then passed out. His gunner, Pilot Officer Frank Albert Toombs, was trapped inside the gun turret. Two soldiers in the vicinity ran up to the crashed aircraft and reportedly could see Toombs struggling inside the gun turret as flames from the fire licked around him, but did not attempt to rescue him.

Many more minutes were to pass before the station medical officer (SMO) arrived on the scene to find the air-gunner still trapped within the gun turret, and that he was now hideously burned.

Showing commendable bravery the SMO pulled Toombs from the inferno and dispatched him with haste to hospital where medical staff worked frantically to treat his terrible burns. Sadly, Frank succumbed to his wounds and died two days later.

18 NOVEMBER

‘The Lawn’ in Hall Road, Rochford, was requisitioned by the RAF as the Officers’ Mess.

19 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officer Rutherford-Jones was promoted to flying officer. Pilot Officer Hughes and Sergeant Lauder of 264 Squadron carried out a night patrol.

20 NOVEMBER

Flight Lieutenant Smith of 264 Squadron carried out two night patrols. Flying Officers Stephenson, Young, Welsh, Melvill and Haigh carried out one patrol, as did Flight Sergeant Thorn and Sergeant Endersby. Pilot Officer Hackwood and his gunner, Pilot Officer Alexander Storrie (43641), were killed shortly after taking off on patrol when their Defiant (N1626) crashed east of Blatches Farm, Rochford.

21 NOVEMBER

Flight Lieutenant Smith, Flying Officer Stephenson, Pilot Officers Young, Welsh, Haigh, Melvill, Flight Sergeant Thorn and Sergeant Endersby of 264 Squadron carried out night patrols.

22 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officer C.H.B. Bassett was posted here for accounting duties.

23 NOVEMBER

Acting Pilot Officer H.M. Friend was posted here for equipment duties. The Station Headquarters moved to the offices in ‘Greenways’ in Hall Road, Rochford.

Squadron Leader Phillip Sanders (36057) arrived to assume command of 264 Squadron.

Flying Officer Sutton and Pilot Officers Gaskell, Frederick Hughes (74706), Percy, Barwell and Curtis of 264 Squadron carried out night patrols. Pilot Officer Hughes observed a searchlight intersection in the vicinity of Braintree and climbed to 7,000ft to investigate. When approaching he noticed at the exact height but 50 yards ahead of the intersection the exhaust flames of a Heinkel III. He engaged it at once as the enemy aircraft was travelling at a much greater speed than his Defiant, and a two-second burst by his gunner Sergeant Fred Gash (146840) destroyed one engine, but unfortunately the turret jammed and at that moment the Defiant was illuminated by three searchlights. At a range of 50 yards from the enemy aircraft Hughes instructed Sergeant Gash to press the trigger while he attempted to manoeuvre the machine so that incendiary bullets struck the Heinkel. In this manoeuvre the aircraft almost collided. The enemy aircraft was again engaged as it crossed the coast and was seen to be losing height rapidly.

24 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officer Gillespie left 264 Squadron on posting and was replaced by Pilot Officer Hallet.

25 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officer J.S. Wood was posted in for code and cypher duties.

26 NOVEMBER

Flight Lieutenant Smith of 264 Squadron carried out two night patrols; Flying Officer Stephenson, Pilot Officers Young, Haigh, Melvill, Curtis, Flight Sergeant Thorn and Sergeant Endersby carried out one patrol.

27 NOVEMBER

264 Squadron left for RAF Debden, continuing their night patrols.

28 NOVEMBER

Pilot Officer T.F. Frost reported for account duties on posting with effect from (w.e.f.) 18 November 1940. He was granted the acting rank of flight lieutenant.

29 NOVEMBER

Acting Pilot Officer C.F. Colyer was posted here for administrative duties with R & R Section. Pilot Officers B. Hale and T.J. Moffatt arrived for defence duties.

DECEMBER

1 DECEMBER

Pilot Officer (Acting Flight Lieutenant) E. Thursfield was posted in from RAF Hornchurch. Wing Commander Embry visited RAF Castle Camps to inspect the aerodrome and accommodation.

3 DECEMBER

Acting Squadron Leader Pleasance, DFC attended a conference at Headquarters, 11 Group.

4 DECEMBER

603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron arrived from RAF Hornchurch, with operational and flying practice starting the following day. This continued until the 13th, when the squadron was moved to RAF Drem. However, they left without Sergeant Pilots Stone and Strawson, who were admitted to Southend Hospital as a result of a motorcycle accident.

5 DECEMBER

603 Squadron carried out operational and practice flying every day until the 13th.

6 DECEMBER

Wing Commander Embry was posted to Headquarters, 12 Group, for Air Staff Night Operations. Pilot Officer A.L. Clow was posted here for duty as adjutant.

13 DECEMBER

At 20.00hrs, officers and around twenty airmen from 611 Squadron arrived by road in private vehicles from RAF Digby. Pilot Officer Clow was posted to 66 Squadron.

The main party of 603 Squadron moved out by train late in the evening to RAF Drem.

14 DECEMBER

At 01.00hrs, a special train carrying the ground party for 611 Squadron arrived at Rochford. Billeting had been organised in empty houses in varying distances up to 3 miles away from this station.

At 13.00hrs, seventeen Spitfires of 611 Squadron landed here, and transport aircraft and five 10-ton trucks arrived during the afternoon carrying more airmen and stores.

Pilot Officers William Assheton (41979), Donald Stanley (83271), and Sergeants Reginald Breeze (516456) and Dudley Gibbins (754428) reported to 611 Squadron on posting from 222 Squadron.

15 DECEMBER

A heavy mist grounded all aircraft today.

16 DECEMBER

Another misty day with no operational flying. 603 Squadron aircraft were also still weather-bound. Pilot Officer Smith re-joined 611 Squadron from sick leave and Flight Sergeant Venn and sixteen others of the rear party arrived by train from RAF Digby, completing the move of the squadron, apart from a few men still on sick leave. Squadron Leader Frederick Hopcroft reported on posting (supernumerary) from 57 OTU, Hawarden.

17 DECEMBER

A fine day today; 603 Squadron finally left for RAF Drem. Two patrols were carried out by 611 Squadron; all aircraft returned without incident.

18 DECEMBER

A misty day; no flying.

19 DECEMBER

A fair day but with a good deal of cloud. One long patrol was carried out in the afternoon by 611 Squadron, above the clouds, on which Blue Section landed at RAF Manston for fuel before returning. Spitfire X4589, recently damaged at RAF Sutton Bridge and repaired there, was collected by one of the pilots, bringing the complement to eighteen aircraft.

20 DECEMBER

An air-raid alarm sounded in the morning; gun posts were manned and opened fire on a lone Dornier which appeared below cloud at about 1,000ft for a few seconds. One aircraft from 611 Squadron went up on a short local patrol afterwards, returning with nothing to report.

Flight Lieutenant A. Cairnie left on attachment to the Officers School at RAF Loughborough.

21 DECEMBER

At 10.40hrs, 611 Squadron took off to rendezvous with 64 Squadron from RAF Hornchurch, and patrolled over the Maidstone patrol line. One section was detached to chase a Dornier over the Thames Estuary, and in fact the whole of the two squadrons intercepted and gave chase. Several pilots landed elsewhere for fuel before returning home, but not all without incident: Pilot Assheton, in Spitfire P9335, taxiing after refuelling at RAF Lympne, sank in a soft patch in a filled bomb crater, damaging the propeller. Flight Lieutenant Barrie Heath (90818) in Spitfire X4644 was about to make an emergency landing in a field near Rye with only 3 gallons showing on his fuel gauge when his engine packed up. He had to land, wheels down, in a ploughed field, but overturned after hitting a bump. The aircraft was severely damaged. Both pilots returned to Southend by train. As if by providence, Spitfire X4662 had been delivered to the squadron the same day by a ferry pilot.

Pilot Officer J. McCubbin was posted here for defence duties.

22 DECEMBER

At 10.40hrs 611 Squadron was ordered to take off and patrol over the base at 10,000ft. On emerging from cloud at 5,000ft the port wing of P9429 (flown by Sergeant Peter Townsend) touched the rudder and tail fin of R6914 (flown by Flying Officer Pollard), cutting pieces off it. Both aircraft landed safely without further damage.

23 DECEMBER

A cold day with cloud. This change for the worse in the weather continued until the 27th. No flying was done.

Pilot Officer Moffatt was attached to the Anti-Gas School at Rollestone Camp for a course.

Earl’s Hall Garage, Southend, was taken over for use as the station workshops.

27 DECEMBER

After a quiet Christmas Day, two aircraft of 611 Squadron, while on practice flights, were vectored towards a raider, and Sergeant Leigh got in a shot at it, but without apparent results. At midday, the whole squadron was sent up for an hour on patrol over the area.

Pilot Officer B.C. Sparrowe was posted here for duty as assistant adjutant, and Wing Commander J.M. Thompson, DFC was posted in to command RAF Southend.

28 DECEMBER

A hazy day meant no operational flying was done.

29 DECEMBER

A clear day; 611 Squadron carried out convoy patrols during which two of the pilots shot at and damaged a Dornier. Pilot Officer Assheton left the squadron for Central Flying School (CFS), Upavon, on posting on an instructor’s course. Flight Sergeant E. Lewis (560863), who had been with the squadron since 1936, received promotion to temporary warrant officer w.e.f. 1 December 1940.

30 DECEMBER

Poor visibility; no operational flying was done.

31 DECEMBER

A few short patrols were carried out in the morning. A new War Establishment (WAR/FC/228 dated 16 December 1940) reduced the pilot establishment from twenty-six to twenty-three, and raised the ground staff from 160 to 166. The principle changes were in the Signal Section, with the introduction of electricians, radio telephony operators, and wireless mechanics, and the deletion of wireless & electrical mechanics and wireless operators. A flight sergeant equipment assistant came in and there were other minor changes.

2

1941

JANUARY

1 JANUARY

A very cold morning; one section of 611 Squadron carried out a convoy patrol at midday. A little later another section took off on an ‘X’ raid, followed by the rest of the squadron on a standing patrol over Gravesend, although nothing was sighted.

The New Year’s Honours List contained the name of the ‘old boy’ of the squadron, Squadron Leader P. Salter, who had been awarded the AFC. The CO also posted a list of nicknames that had been allocated following suggestions some months ago: ‘Charlie Two’ Hopcroft, ‘Lofty’ Langley, ‘Drunken Duncan’ (Pilot Officer W.G.G.D. Smith), ‘Tweakie’ Askew, ‘Singapore’ Stanley, ‘Tubby’ Garrett, ‘Mushroom’ (Sergeant N.J. Smith), ‘Limshilling’ Limpenny, ‘Tubby’ Townsend, ‘Dai’ Williams, and ‘Gubbins’ Gibbins.

Acting Squadron Leader Pleasance, DFC was posted to Headquarters, 12 Group, and Flying Officer Nobbs was posted to 66 Squadron.

2 JANUARY

A cold morning with a dusting of snow over the aerodrome. Two short test flights were carried out, but no other Spitfire flying took place today. Warrant Officer Lewis left the squadron to take up a posting at the Aircraft Gun Mounting Establishment at Duxford.

3 JANUARY

Another cold day. At 08.25hrs, one aircraft of 611 Squadron carried out a lone patrol, but there was no other operational flying. Spitfire X4547 was returned to the squadron after repairs carried out at RAF Digby.

Acting Flight Lieutenant D. Edwards was posted from this station to RAF Wittering, and Flight Lieutenant J.L.W. Walls (Medical) and Flying Officer J. McIntosh (Engineering) were posted in. Flight Lieutenant Walls was granted the acting rank of squadron leader upon his arrival. Flying Officer Cargill was posted to 145 Squadron.

4 JANUARY

Snow still on the ground; one section of 611 Squadron flew a patrol in the morning, and returned with nothing to report.

Pilot Officer J. Sutton (90758) joined the squadron on attachment from RAF Digby, after a period of sickness. Flying Officer J. McIntosh was granted the acting rank of flight lieutenant.

5 JANUARY

A milder morning, but no signs of a thaw yet; some practice flying was done by aircraft of 611 Squadron. Pilot Officer T.J. Moffatt returned from attachment to Rollestone Camp.

6 JANUARY

A freeze-up again followed by more snow. Two aircraft from 611 Squadron carried out a local patrol, but visibility was too bad for them to see if anything else was flying.

7 JANUARY

The sky was overcast for much of the day and no flying was done, but at around tea time, three Lewis and three Hispano guns of Ground Defence opened fire (without success) on a lone enemy aircraft as it attacked the aerodrome. It dropped eight bombs (thought to be 50kg), three of which fell on the aerodrome. There were no casualties sustained and although the attack resulted in three craters, the aerodrome remained serviceable.

8 JANUARY

Although there were signs of a slight thaw in the afternoon, no flying was done today.

9 JANUARY

A clear and bright, if somewhat cold morning; one section of 611 Squadron carried out a local patrol and later in the morning the squadron patrolled over the Maidstone line.

10 JANUARY

At 12.00hrs, 611 Squadron took off to join other fighter squadrons escorting six Bristol Blenheims on an offensive sweep behind Calais. Light anti-aircraft fire was experienced, some of which made a hole in the tailplane of Squadron Leader Hopcroft’s aircraft. ‘A’ Flight, led by Squadron Leader Ernest Bitmead (34139), put in some ground strafing near Wissant on the way home. The CO made an amendment to the list of nicknames he had posted on 1 January; against Hopcroft he deleted ‘Charlie Two’ and substituted ‘Ack-Ack Charlie’.

Flight Lieutenant Cairnie returned to the base for a ten-day attachment (until the 20th) from RAF Loughborough.

11 JANUARY

A slight improvement in the weather; thaw set in overnight and most of the snow was cleared by the morning. Two short patrols were carried out by aircraft of 611 Squadron, but returned with nothing to report.

12 JANUARY

One patrol and some local flying practice were carried out by 611 Squadron.

13 JANUARY

No operational flying was done until the 16th owing to bad weather.

14 JANUARY

Squadron Leader Hopcroft, DFC left 611 Squadron on posting to RAF Hawkinge to command 91 Squadron, latterly known as 421 Flight.

16 JANUARY

With a break in the weather, some local flying practice was carried out by 611 Squadron.

17 JANUARY

Some uneventful patrols were carried out by 611 Squadron including one over a convoy of sixty-four ships in line astern. Temporary Squadron Leader Eric Michelmore (37112) reported to the squadron on posting supernumerary for flying duties from 57 OTU, Hawarden.

18 JANUARY

More snowfall overnight meant no flying was done today.

19 JANUARY

A heavy thaw overnight with some rain; during a convoy patrol in the morning by 611 Squadron, pilots caught a glimpse of an enemy aircraft, but took no action because of dense cloud. Squadron Leader Hopcroft, DFC arrived back from RAF Hawkinge on reposting to the squadron.

20 JANUARY

Rain and thaw all day; the aerodrome had become bogged and unserviceable – no flying was done. Temporary Squadron Leader Michelmore left 611 Squadron for RAF Biggin Hill, on attachment to 74 Squadron, pending posting.

21 JANUARY

A mild day with some drizzle; 611 Squadron carried out local patrols by a succession of single aircraft. Instructions were received that the squadron would be moving to RAF Hornchurch on Monday the 27th, exchanging with 64 Squadron.

22 JANUARY

A fair day; during flying practice in the morning, Pilot Officer Smith was vectored by Operations in chase of a bandit, but did not get the opportunity to engage it. Sergeant Eric Limpenny (189635) was on his take-off run in Spitfire X4620 when it sank in a filled bomb crater and nosed up, causing damage to the propeller and one oleo leg. Sergeant Limpenny was unhurt.

23 JANUARY

Mist and low cloud limited flying; one aircraft of 611 Squadron started a local patrol, but returned at once owing to severely reduced visibility.

24 JANUARY

A heavy mist and visibility reduced to no more than 200 yards meant there was no flying.

25 JANUARY

No flying again owing to heavy mist. Sergeant Limpenny went to Halston Hospital for diagnosis.

26 JANUARY

Again a very misty day; one aircraft of 611 Squadron went on patrol and returned with nothing to report.

27 JANUARY

Four thirty-two-seater coaches and four 3-ton lorries arrived last night from the Transport Pool at Cambridge, and a similar convoy went to RAF Hornchurch. At 09.00hrs the Southend vehicles loaded up with the first road party, consisting of half of each flight and section. They arrived at RAF Hornchurch at around 10.45hrs.

Meanwhile a similar half of 64 Squadron was brought here by the Hornchurch vehicles. At 13.00hrs, each convoy was reloaded for a return journey with the second halves of the squadrons. A few extra vehicles from Station Transport assisted with baggage and gear. The move proceeded with extreme smoothness, and transporting the men in this manner, both squadrons remained fully operational throughout the move.

The dispersal points at the aerodrome were manned from dawn by personnel of 611 Squadron detailed for the second road party. They were relieved about midday by the first arrivals of 64 Squadron from RAF Hornchurch where there was a similar change over. The aircraft were changed one section at a time; flying conditions were extremely difficult. By 17.00hrs the move of both squadrons was compete. The squadron strength at the end of the month was eighteen officers and 236 other ranks.

FEBRUARY

2 FEBRUARY

At 09.30hrs, eleven Spitfires of 64 Squadron took off on patrol over the English Channel but no contact with the enemy was made, and they landed back here at 11.05hrs, but without three of their aircraft which had to make forced landings through lack of fuel. Sergeant Tony Cooper in Spitfire P4690 went down 1 mile north-west of Eastchurch, Sergeant Allan in Spitfire P4448 went down near Faversham, Kent, and Pilot Officer Percival Beake (84923) in Spitfire P4626 went down at Shepherd’s Well, Kent.

3 FEBRUARY

Eight Spitfires of 64 Squadron took off on patrol between 11.45hrs and 15.45hrs, but no contact with the enemy was made and all aircraft returned safely.

4 FEBRUARY

Spitfires of 64 Squadron carried out patrols in twos and threes between 13.50hrs and 17.50hrs, but all returned with nothing to report.

5 FEBRUARY

64 Squadron carried out uneventful patrols between 09.55hrs and 17.10hrs.