Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Spellmount

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

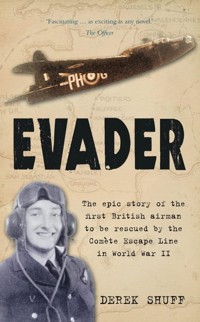

In 1941 air gunner Sergeant Jack Newton's Wellington is hit by flak on his first bombing raid over Germany. Miraculously, the skipper makes an emergency landing on a German-occupied Belgian airfield, narrowly avoiding Antwerp Cathedral. Having torched the plane, the crew give the unsuspecting Germans the slip and are hidden by the Resistance. Hoping to make it to the coast and back across the Channel, the airmen are surprised when the 23-year-old female leader of the Comete Escape Line, Andree de Jongh – codenamed Dedee – has other plans for them. Full of terrifying and humorous moments, this is the story of the epic journey of the first British airman to escape occupied Europe during the Second World War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 397

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

EVADER

EVADER

The epic story of the first British airman to be rescued by the Comète Escape Line in World War II

DEREK SHUFF

First published in 2003

This edition published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Derek Shuff, 2003, 2007, 2010

The right of Derek Shuff to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5149 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Dedications

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

I

The Early Days

II

Doing the Business

III

Dropping in on Antwerp

IV

Tangle with the Enemy

V

Train Trip Trouble

VI

‘Little Mother’

VII

Mary’s Love Diary

VIII

Walking with the Enemy

IX

Can I Cross the Pyrénées?

X

Bitterness of Failure

XI

Rickety Rope Bridge

XII

Safely Delivered

XIII

Smuggled into Gibraltar

XIV

Back Home!

Conclusion

Why it is Lucky 13 for me …

Dedications

To Flight Lieutenant Roy Langlois DFC who saved my life; to Countess A. de Jongh, who gave me those extra years of freedom. And to my wife, Mary, who never gave up hope.

Jack Newton

To the Jack Newtons of World War II who willingly took a step into hell that the rest of us would live in peace and freedom. To my mother, Hilda Shuff, who braved Hitler’s wrath throughout the duration of the war by carrying on living and working in South Godstone, Surrey, underneath the skyway used by Nazi bombers, flying bombs and rockets. To bravery with honour wherever it is found.

Derek Shuff

Acknowledgements

Jack and Mary Newton, for their many memories and their unstinting help (along with many cups of tea and fruit cake!); Countess Andrée de Jongh (Dédée), for making this book possible; to her companion, Thérèse de Wael, for her patience with my questions. To Peter Presence, for his early cooperation; Richard ‘Tich’ Copley, for his graphic recall of being ‘on the run’ in Brussels, and to his wife, Betty, who collated his material. I am indebted to Airey Neave’s Little Cyclone which featured the heroes and heroines of the Comète Escape Line, many of whom, between them, saved Jack’s life and, in turn, helped me to convey the horror of the events through which they lived and, in some cases, died, and to Betty Ames, who provided the watercolour painting used on the front cover. In fact, my thanks to all those who assisted in even the smallest way.

Preface

by Countess Andrée de Jongh, GM

(Dédée)

I could not accept that a race, because of its blond hair and blue eyes, that this type of people would consider itself to be superior to all others, that it would rule, and that all other races would be considered sub-human. Could one passively allow such a thing to happen? No, it is better to die fighting than to accept such horrors … even if some of us had to lose family, or friends. Such commitment goes hand-in-hand with great sacrifice, and those of us in the Comète Line had more than our share of personal misery.

For nearly four years we fought our underground campaign to rid our beloved homeland of the German invaders and occupiers. What made our motivation stronger was the privilege of guiding among the escapees so many very young airmen full of courage and so eager to reach Gibraltar in order to return to the battle. And when the Germans finally succumbed, we knew our blood, sweat and many tears had been worth it, even though, in my case, I lost my beloved father who helped me set up the Comète Line. He was executed by a German firing squad in March 1944, sadly just a few months before Belgium was liberated. Many other helpers also gave their lives saving the lives of those like the first English airman I helped, Jack Newton, Royal Air Force, whose story is the subject of this book. Now it is up to present and future generations to ensure that Europe is never again blighted by the cancer of race domination, but this calls for extreme and constant watchfulness.

Enough blood has been spilled. Enough unhappiness unleashed on so many innocent peoples. The future must be paved with tolerance and, above all, with happiness.

As for those of us who helped create this brighter future, I can only add: Don’t thank us, we had the joy of fighting, without striking a blow.

Brussels

Introduction

Since the first publication of Evader I have made many new friends, both in Britain and abroad. But I have since lost the closest one of them all – my dear friend Jack Newton whose courageous World War II story I was privileged to be able to tell. Sadly, Jack died peacefully in The Conquest Hospital, Hastings, on 27 January 2004 after a short illness. He was aged eighty-four. The one consoling factor being that when I set out to write Jack’s extraordinary wartime experiences, the first thing he said to me was, ‘I do hope I live long enough to see my story in print!’ Well, he did and I will never forget the look of pride on his face when he took delivery of the first copy of his book. His happy, smiling face told it all.

Even so, it was a very difficult time for Jack’s wife, Mary, who had always been by his side through thick and thin, but her strong and supportive family helped her through. The fact that Evader was a huge success also proved a comfort, and brought new friends into Mary’s life, too.

I was inundated with letters, phone calls and emails from readers who simply wanted to say that they found Jack Newton’s story so inspiring. Many older readers also enriched my life by telling me of their own wartime experiences. One man contacted me to say that he and his wife were so inspired by the book that they planned to spend their summer holiday travelling along the precise route that Jack Newton took, from Belgium, through France, across the Pyrénées to the British Embassy in San Sebastian. Only, of course, their journey, unlike Jack’s, was to be in a free Europe, and not under German occupation as it was in 1941 when it took Jack many months, rather than a two week’s sightseeing holiday trip that it would be today! Happily, I can record that at the time of writing Dédée (Countess Andrée de Jongh) is still alive and well, apart from her failing eyesight.

I first saw Jack on television. He was being interviewed in connection with his visit to Brussels for the last reunion meeting of the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society and the Comète Escape Line. Queen Fabiola was there to pay tribute to her country’s Resistance movement and to the Royal Air Force escapers. As one of Belgium’s best-known and most decorated members of the Resistance, Andrée de Jongh was at this last reunion, too.

I heard how Jack’s Wellington bomber had forced landed in Belgium, that he had been saved by Andrée de Jongh, who had been honoured with the title of Countess for wartime services to her country. That she had been instrumental in getting the young airman, Jack Newton, safely back to Britain. But how? And what had happened between Jack’s untimely appearance in Belgium, then under Nazi occupation, and his return to London, via Spain, some five months later? I had to find out!

One phone call and I had an invitation to the Newton home in Broad Oak, ironically barely three miles from my own home in East Sussex. A couple of days later, Jack gave me a shortened account of his amazing story, accompanied by several cups of tea and slices of fruit cake, served up by his equally involved wife, Mary.

Tea at the Newtons’ was to be the beginning of our collaboration on Jack and Mary’s story. ‘Let’s hope I am around long enough for you to finish it,’ said the sprightly 82-year-old former air gunner, one of the so-called ‘tailend Charlies’. There didn’t seem to be much doubt that he would be. Jack Newton was still focused, energetic and enthusiastic about the part he played in evading the Nazis whose nationwide dragnet across France failed to catch him. And his recall of those 1941 events remains as crystal clear as the water of the fast flowing Bidassoa river that was nearly his final downfall.

Of Dédée, Jack said he owed her his life. He told how living on the very edge of life and death for so many weeks created a bond like no other. A bond that survived up to his death. Dédée was to suffer inhumanely at the hands of her German captors, but somehow she bravely survived all the horrors of internment and, in 1946, renewed contact with Jack Newton, ‘My brave young airman’, as she liked to call him. Being the first British airman to evade capture in German-occupied Europe in the Second World War, he had remained rather special to Dédée, and they maintained personal and monthly telephone contact with each other for most of the time up to Jack’s death.

Jack liked to tell how he had been blessed with two wives – Mary, the woman he married some twelve weeks before he flew to Aachen on that ill-fated raid, and Dédée, to whom he stressed he owed his life. He said he loved them both.

When Jack Newton and those brave souls such as Dédée were existing under Nazi rule, with discovery and death just a bullet away, I was a 6-year-old schoolboy living in South Godstone, Surrey, totally oblivious to the dangers that confronted those given the task of facing and beating the enemy.

So, I hope that Jack Newton’s story, and the story of the many brave people who helped to save him, will never be forgotten. And if a book like this helps to keep those memories alive, then the sacrifices of so many dedicated men and women have not been in vain.

Having spent many hours talking to Jack Newton, and researching and writing his story, one question still remains. That is: why was Jack Newton’s courage never officially recognised? Others involved in his story rightly received the highest honours the British government could bestow on them when the war was over. But for the first airman to make it back to Britain … nothing. Not even a letter of commendation. Even the efforts of Naval Lieutenant Commander Grisar, who knew what Newton had been through, came to nothing. ‘At the time, the Air Ministry simply said I had done nothing out of the ordinary!’ said Jack, a little sadly. ‘It would have been nice to, at least, have had an official letter, or something. I was the first, and it wasn’t exactly a joyride. But I think such personal achievements, especially in the beginning of the war, were largely lost in the increasing momentum of the war effort.’

Postscript, 2010

It is with deep regret that I have to record the deaths of the two women who featured so prominently in Jack Newton’s lifetime. They are Jack’s wife Mary and Countess Andrée de Jongh who, as the Comète Line resistance leader codenamed Dédée, gave hundreds of Allied servicemen like Jack many extra years of freedom.

Countess Andrée de Jongh died in Brussels on 13 October 2007, aged ninety.

Mary Newton died in St Michael’s Hospice, Hastings, on 17 November 2007.

I

The Early Days

Jack Lamport Newton was born in a hayloft on 4 February 1920, although the hayloft had long since been converted into a cosy flat, and the stables below it into a garage where chauffeur John Lamport Newton kept and looked after the guvnor’s cars. They lived there for twenty-five years in a very smart part of Hampstead, in north London, through the generosity of John’s employer, Mr Johnson, of Johnson and Johnson, the famous baby powder company, who provided his chauffeur with the courtesy flat, and £5 a week wage.

It was in this atmosphere of gracious living, stylish and fast cars, as well as a lifestyle that must have been the envy of his school pals, that young Jack and his elder sister, Babs, spent their formative years enjoying the many benefits and privileges which came their way at 13 Lancaster Mews. Mr Johnson was a kindly man who loved expensive cars, and being well able to afford them, the ‘shop’ – the family’s pet name for the garage – was filled with some of the choicest models around at the time. Cars such as the 90 horse power Fiat, and the superb Issota Frashini, to name just two. A stable once filled with horses was now full of high horse power cars. The irony was not lost on Jack. He became nearly as obsessed with the sleek and beautiful horseless carriages as his father, and Mr Johnson, too. Mr Johnson’s cars were his pride and joy, and when he could take a couple of weeks away from his business he liked nothing more than to have chauffeur Newton drive him off to Spain where the roads were long, straight and empty. ‘Come on, dear chap, put your foot down. Open up. Let’s see what she can do,’ he’d say encouragingly, as John put the powerful Fiat through its paces.

On one such trip, the two of them fell foul of some Spanish brigands. Up in the hills around Granada, old Mr Johnson and his chauffeur were suddenly confronted by a gang of ruffians who stood across the road waving guns, hoping to stop the car. Their intentions were pretty clear. ‘Go through them, Newton. Drive on …’ ordered the old man, as though he was leading a cavalry charge. The two men put their heads down, and drove straight at the gang who had to throw themselves either side of the road to avoid being run down. Shots were fired as the car raced away, one missile hitting John Newton in the wrist. Even so, he kept control of the vehicle and continued driving until they reached safety – and a hospital.

John’s favourite snack was dripping on toast. He loved it. Gus, as his wife was nicknamed, made him lightly browned toast, and John piled the dripping on so thick it fell off the sides. Then he would cut each slice into four, pop a quarter into his mouth at a time, and savour the flavour for as long as possible before swallowing. After that, he popped in the next piece, and the next until it was all consumed. Jack would watch mesmerised. He recalls:

Mum was one of six sisters who all came from Fareham, in Hampshire. Mum’s father, Granddad Lamport, was a local butcher, which must have been where dad got his taste for fresh dripping. Each weekend we always had a package from our own family butcher consisting of a couple of pounds of sausages, some pieces of meat, some bacon, and some things unheard of now called chitlings. Also, there would be black pudding and dad’s tub of dripping. All delivered promptly on the same day to Lancaster Mews.

We lived in Hampstead until I was about 11, then we moved to what we called the backside of Mr Johnson’s house, which was on Avenue Road, St John’s Wood. It was quite near to Primrose Hill and Regent’s Park. Mr Johnson had a very large garden, with a sizeable plot of undeveloped land one side, and on the other was a little yellow brick house. It was on the plot of vacant land that Mr Johnson had the house built for Dad; our new home, 30-2 Townshend Road, St John’s Wood. The big, detached house with two garages and huge glass awnings over both garages, cost about £3,000 in those days. I cannot imagine what it would go for today. But the great thing about living on Townshend Road, I went to Barrow Hill Road School, in St John’s Wood High Street, which was barely three minutes’ walk away.

By this time Dad chauffeured Mr Johnson around in a Le Mons 3.5 Bentley, as well as an Armstrong Siddeley, both kept and cared for in our double garage. The son had a Lancia, and Dad kept that up to scratch, too. When I bought my favourite little MG, Mr Johnson gave me permission to keep it in one of the garages.

Considering we lived rent free, my Dad’s fiver a week take home pay allowed us to live well. We had a wonderful time. On top of that, we had a family holiday in Bournemouth once a year.

My sister and I loved those holidays. London was always interesting, but the sand and the fresh air in Bournemouth was something quite special. My sister’s full name is Emalia Hilda Madge Newton, a bit of a mouthful which was why we called her ‘Babs’. The Emalia was something to do with my Dad’s love of Spain, and anything Spanish. I believe he’d heard the name on one of his Spanish jaunts and when my sister came along, his firstborn, she just had to be named ‘Emalia’. Babs wasn’t impressed. She liked to be called Babs, or Madge.

There were only the two of us. Like me, Babs is still around, but she hasn’t been too well of late, having just lost her husband who was nearly 100. So, at this time of writing, she is in a nursing home in Wales. Babs is seven years older than me, so she is knocking on 90.

Life in Townshend Road was good for the chauffeur’s young son, but one day he noticed a family moving into number 42, a few houses along, and suddenly thought being there showed every sign of getting still better! Jack’s eye had caught sight of the new family’s pretty 13-year-old daughter, Mary. That evening, before bed, he asked his mother if she knew anything about the new people. ‘The husband is like your dad, he’s a chauffeur,’ she told him. ‘That’s all I know …’ Apart from the pretty daughter, Jack soon found out she had two younger brothers. Mary’s father was a dour Scotsman and a member of the Royal Scots Greys. Apart from being a chauffeur, he was already a friend of Jack’s dad.

Every Sunday, Mary and the two boys who were turned out in kilts, sporrans, and little buttoned black shoes, were taken to church. After a while, Jack and Mary began talking to each other. Then Jack plucked up courage and started calling at her house. He wasn’t always made welcome. Sometimes he would knock, and Mary’s father would tell him to ‘Go away … she’s too busy.’ ‘Yes, I’d get shooed off,’ he says. But he persevered. There was an old gas lamp-post outside, and Jack found that if he climbed to the top of it, he could see into Mary’s bedroom. When his welcome wore thin at the front door, Mary opened her bedroom window, Jack shinned up the lamp-post and they chatted until Mary was called away.

Jack was getting on well with Mary, but the more it looked that way to her father, the more he showed it irritated him. Some evenings they would take Mary’s dog for a walk, but when Jack called at her house to pick her up he was told precisely when Mary had to be back home. If it was nine o’clock, then her dad was on the doorstep waiting, looking at his watch as if he was counting down the seconds. It didn’t make courting Mary easy for the lad. But young love conquers, and Mary had conquered Jack’s heart. They became sweethearts.

I then passed one or two primary school exams and as Dad always wanted me to do something in the technical line, my parents managed to scrape enough money together to send me to the Regent Street Polytechnic. It was a sort of technical grammar school. The main school was on Regent Street and the technical side in Little Titchfield Street, alongside Broadcasting House, which was where I went each day. In four years, I did pretty well, passing most of the technical exams I sat in drawing and light engineering.

Then I applied for a job as a draughtsman at the Air Ministry. It had nothing to do with flying because the closest interest I’d shown in anything aeronautical at the time was putting together plastic model planes. Not even a plastic Wellington! Anyway, the Air Ministry didn’t want me, or more to the point, they said they hadn’t any places left to offer me. The only engineering job I could find was with the Post Office, so I was recruited into the Farm Street Exchange as a ‘Cord Boy’; this exchange being the largest in Europe. Well, it was a start.

I went to hotels and big offices to mend switchboard cords. To wire up three-pin plugs, and clean them. I was known as the visiting cord boy. The Dorchester and The Grosvenor Hotels were both in my area. I was paid one pound four shillings and sixpence a week, which was pretty good money for a civil servant in those days.

When Germany began throwing its weight around in Europe, war fever began to get a hold of everyone, and I was no exception. I had three pals; one I’d met at work and the other two were Fleet Street journalists. We agreed we wanted to become pilots, so in 1938 we trotted along to Store Street, off Tottenham Court Road, and signed on with the RAF Volunteer Reserve. We attended training lectures on Store Street, and took part in weekend camps, which included some flying. Then I was posted to the De Havilland School of Flying, No. 13 Elementary and Reserve Flying Training School, based in Maidenhead. We all trooped off there once or twice a week to familiarise ourselves with flying a couple of the aircraft they kept there – a Tiger Moth and the Hawker Hind. Both planes were painted yellow to show they were trainers.

It was there that I began to get really interested in flying. We’d go off for about half an hour, doing circuits and bumps (landing and take-offs), and a bit of cross country flying, too. I loved it, and believed I was becoming a pretty good pilot. Unfortunately, this wasn’t a view shared by my instructor, especially after I returned from an afternoon training flight and came in to land just a bit too high. I had the choice of either opening up and going round again, or desperately putting the plane down firmly on the runway and hoping for the best. Unfortunately, I made the wrong choice – I went for the landing. It was more of a crash landing. One wingtip hit the ground ahead of the wheels, and bits fell off everywhere before me and my machine came to a crunching halt.

The little man from the control tower insisted I called in with my logbook before I left the airfield. When I reached the tower I could see he hadn’t asked me over to sympathise. The little man took my logbook and endorsed it with the comment: ‘Sergeant Newton will most likely make a very efficient pilot, but not up to the standards required by His Majesty’s Air Force.’ In short, there was no way they’d take me as a pilot, though my other three chums passed. It also meant I had lost the sergeant status given to trainee pilots, being instantly demoted back to the humble rank of AC2.

That left me with only one option if I wanted to be a flyer, as I did, and that was to settle for being an air gunner.

Shortly after 3 September 1939, the day war was declared on Germany, Jack had a letter from the Air Ministry addressed to Sergeant J.L. Newton. It instructed him to go to Store Street to pick up his uniform, his three tapes and little brevet hat. He felt great, and whoopee, he was still a sergeant.

I thought they had forgotten I had smashed up an aircraft, that I had been given another chance. All my friends were thinking, ‘Jack must be jolly good. War has only just started and he’s already a sergeant!’

But the following week an urgent telegram arrived at the Newton home in St John’s Wood informing him there had been a mistake. He was told to hand in his sergeant’s tapes because he was back to being an AC2, regarded as the lowest of the low.

His employer, the Post Office, thought he was crazy to want to give up his job to fly. He was a civil servant and in a reserved occupation, so he could have seen the war out as a civilian. That wasn’t for Jack Newton, so the only chance he had to get back into the air was to take on a job that nobody else wanted – as a rear gunner, or a ‘tailend Charlie’, as they were called in those days.

His family, his friends, his girlfriend, Mary, they all suggested there might be a safer job for him to do if he really had his heart set on joining the Royal Air Force. ‘I’d been bitten by the flying bug at Maidenhead, so it didn’t bother me a damn that being a rear gunner was dangerous. Just as long as I was back in an aircraft.’

After some hanging around at home, waiting to be called up as a trainee air gunner, Jack was posted to the Eversfield Hotel, in Hastings, to do his initial training. It was the home of all the gunners and wireless operators. The next hotel along the road was for observers, and the palatial Marine Court was for pilots. ‘So, the RAF didn’t think much of us gunners, stuck in the lowly Eversfield, the worst hotel of the three!’ said Jack. He did nine months’ training without even catching sight of an aeroplane, other than the ones over-flying the town. Nor did he get his hands on a gun, not even those in the seaside town’s amusement arcades! There were plenty of lectures, aircraft recognition tests, cross country running – presumably to keep him fit – and once a week pay parades in the underground car park. When it was wet, some of the outdoor activities took place in what was called ‘Bottle Alley’, a covered walkway beneath the seafront promenade that got its name because its walls were made with broken beer bottles and glasses. And when the NCOs (Noncommissioned Officers) in charge felt really bloody minded, they sent the men to run round Warrior Square ten times before collecting their pay.

Jack Newton stuck it out for nine months. Then came the plethora of inoculations for tetanus, yellow fever, smallpox, ‘flu … everything, it seemed, except swine fever!

They gave us those at the Grand Hotel, on the seafront. I had to sit on a long form, put my right arm on my hip, leaving it there until this medic had given me the three jabs in one arm, and another two in the other arm. That was OK because they gave us our jabs on a Friday so we could have a free weekend to get over them. I made my way up through Warrior Square to the railway station to get myself back to St John’s Wood. On the way, I remember seeing quite a few AC2s hanging onto railings trying to catch their breath, groaning with their aches and pains from the effects of the inoculations!

Now for some real action. A posting to an operational training, No. 11 OTU Bassingbourn, in Cambridgeshire. Jack was able to familiarise himself with the Wellington 1c, the version with radial engines, and log a good number of hours in the process. Not too far away, in Gloucestershire, Frank Whittle was assembling his revolutionary jet engine at this time in 1940 and there were fears the Germans might parachute in saboteurs to wreck his work. Jack was one of those selected to undertake special guard duties on the site where the engine was being put together. Night fighters at Staverton, Jack’s new posting, patrolled the skies in the area ready to confront any possible German attack. Fortunately, the Jerries stayed away.

Intense training continued on the ground and in the air as Newton went from Fairey Battles to Defiants, to Wellingtons, to understand all the complexities of the weapons that might help to save his own life, and those of his crewmates when he eventually went on operational bombing raids over Germany.

Then it was celebration time once more when the Royal Air Force gave him back his three stripes. He was a sergeant aircrew again, proudly wearing his stripes and his air gunner’s winged brevet with AG embossed on it.

Aircrew were given minimum sergeant’s rank, rather than LAC (Leading Aircraftsman) because if they were shot down the Germans treated the higher rank of non-commissioned officer with more respect than an LAC.

What about Mary? Was she concerned that the man who was now her fiancé (they became engaged just before she was 18) was putting his life well and truly on the line as an air gunner?

I don’t think she looked at it that way. Mary was happy that I was doing what I wanted to do. In any case, with war now a part of everyone’s life, we each lived one day at a time. When I saw Mary, we’d go to the cinema, take walks together, and we did a lot of cycling. I had a racing bike and Mary often came to see me speeding round the wooden race track in Paddington. Then there was my favourite MG sports car which we enjoyed taking out for a spin. Mary wrote to me every day, as she did when I was miles from her and home at Grimsby, in Lincolnshire, but there were never any recriminations in her letters at what I was doing, and the risks involved.

From gunnery school Newton was posted back to Bassingbourn around the end of 1940 and remained there training on Wellingtons. He hadn’t seen any action, as yet. That happened when he flew as air gunner in Defiants, but this turned out to be primarily defensive patrolling. There was always the chance the Jerries might send over Junkers 52, loaded with paratroopers, in which case he’d have been up there in the front line. But they got cold feet!

I can’t say I was itching to get into action. I was quite happy with what I was doing. Then at the end of 1940 I was posted to RAF Binbrook, just outside Grimsby, to be attached to 12 Squadron which was known as ‘The Dirty Dozen’, or ‘Thirteen Bar One’. The squadron emblem was a fox’s head, with the motto ‘We Lead the Field’. In fact, 12 Squadron did lead the field, too. It was the first squadron to gain VCs (Victoria Cross) on Fairey Battles and its crews bombed the Maastricht bridges on the Meuse. Tich Copley, my Wimpy wireless operator, actually bailed out of his Fairey Battle over the Meuse. The Germans sent out a team to pick him up, as did the British. Luckily for him, the Brits got to him first! So he had been in action before we got together on ‘G for George’.

The crew began operational flights littering occupied France and Belgium with thousands of leaflets to reassure the local populations the British were their friends. And fighting for their freedom.

It was the beginning of a bizarre story that was to give air gunner Jack Newton experiences he would cherish for the rest of his life. And many friends all bonded by their defiance of an enemy that tried – and eventually failed – to dominate Europe and its peoples.

II

Doing the Business

Jack Newton checks his watch. It is 2320 precisely on a blustery, moonlit night with very little left of Tuesday 5 August 1941. From his front gun turret he can see heavily broken low-layer cloud scudding across the sky, the snowy-white face of the old man in the moon popping in and out of view like the star of some heavenly peep show, and casting its reflected eerie glow on their bomber which will shortly be lined up for take-off. Binbrook’s main runway is still glistening from a heavy evening dew. Nine of the ten Wellingtons from 12 Squadron on this bombing mission have already lifted off the concrete strip and are now climbing steadily eastwards, outward bound over the surrounding Lincolnshire countryside. But ‘G for George’ is forty minutes late, delayed by a faulty rear gun turret. It is to have interesting consequences.

‘We’re off,’ says Jack to himself as skipper Roy Langlois gets the green light from the runway air traffic control caravan.

Langlois turns the ‘Wimpy’ onto the runway, and lines up ready for take-off. At 2325 it is time to go. A Verey flare, fired from the caravan, arcs high into the summer night sky. ‘Power on,’ snaps Langlois as he eases the twin throttles forward. The Wellington’s two high-performance Merlin engines roar into life, but with its brakes applied it remains restrained like a big bull elephant eager to taste freedom, yet held fast because it is still tethered to its post. Suddenly there’s a jolt as the skipper releases the brakes, unshackling the beast, allowing the huge, trembling machine to begin its lumbering take-off. From his front gunner’s turret – the ‘office’ as he likes to call his metal and plastic gun bubble — Sergeant Jack Newton has the best view of the flight ahead. But it is also one of the two most dangerous crew positions on board, the other being the rear gun turret.

His eyes scan the concrete strip. His ears tune into the healthy whine of the hardworking Merlins as they pull the heavily laden bomber faster and faster over the ground. The tail rises gracefully as though some unseen force is giving it a helping hand into the sky. There is one small bounce, and she is airborne. ‘We’re on our way … at last,’ calls the skipper cheerily over the intercom to his five other crew members. His confident and reassuring voice crackling into their headsets is now the only contact they have with their skipper, and with each other.

Langlois eases W5421G, callsign ‘G for George’, slowly into the night sky on the first leg of the flight which will take it above enemy territory for its operational bombing raid over Aachen, on the Belgian/German border, a border that Hitler’s ruthless military machine erased in a single crushing invasion on 10 May 1940. ‘Binbrook control. G for George airborne at 2330 …’. ‘Roger, G for George. Continue your climb. Call when you clear the coast off Grimsby …’. ‘Binbrook – wilco.’

Up to now. Jack and the crew have been largely engaged on leaflet raids over Paris, Brussels and Innsbruck. Not really the kind of action Jack had in mind when he signed on as aircrew, but these raids still carry considerable risk and are classed as operational. It always amuses him that he is being a bit of a litterbug, dumping thousands of leaflets over Paris on these flights. In May 1941 it is a popular form of propaganda, although by 1943 other crews are dropping what look like mini French newspapers called ‘Le Courier de l’Aire’. The Paris street cleaners must be thoroughly fed up, unless the Germans pay them overtime!

By 1941 the Battle of Britain, which came to a head on 15 September 1940, had already been won. Now it is time to take the air war increasingly to Germany to crush its industrial power. His crew training completed, Jack Newton is heading for Aachen. Instead of leaflet raids, this time the deliveries are an arsenal of bombs they hope will help blast a tyre factory and an important railway marshalling yard into oblivion. One 1,000lb general purpose bomb, three 500lb general-purpose bombs, one 2501b general purpose bomb and sixteen 25lb incendiaries will certainly bloody Hitler’s nose. But first they, and the four other 12 Squadron Wellingtons on this Aachen raid must get to their target, do the business, and make it back home safely. Another five Wimpys are on a simultaneous bombing mission to Karlsruhe. It is going to be a long night for each of them.

The heavy, sweaty odour of nervousness hangs in the air inside Jack’s aircraft. The crew’s training has been thorough and Jack hopes this is the first of many such bombing raids which will give him the personal pleasure of striking back at Jerry. He has already come to terms with the fact that front and tail gunners are the most vulnerable, with a life expectancy that at the height of the war is to become as low as five ops. This night, however, Jack should have been tucked snugly into the tailend gun pod, but for some reason – and he didn’t ask why – Doug Porteous, the crew’s usual front gunner, asked Jack to change places. The skipper had no objection so Jack happily obliged. ‘What the hell. Might as well get blasted with German cannon in the front turret as the rear one!’ But behind this skittishness he has a strange belief in his own immortality. It just never occurs to him that something so awful might really happen. Besides, he married his childhood sweetheart, Mary, some twelve weeks before, with only time for just three nights proper honeymoon together at Bourton-on-the-Water, in the Cotswolds. Then Mary came up from London to Binbrook to the rented cottage Jack had booked for them over that August Bank Holiday weekend; a two-day extension of their honeymoon that was sadly so short, but happily so sweet. That sweetness is still uppermost in his mind. During the quieter moments on the flight to Germany, his heart and head are full of thoughts of Mary, rather than of the Aachen factories and marshalling yards he knows he will have to concentrate on soon enough. In any case, Jack believes that by 0800 the following morning, ‘G for George’ will be touching down at Binbrook – its job done. Back to a huge breakfast. Back to his beloved Mary.

Right now, though, he must focus on the outward trip. It is so easy to leap ahead, make plans, but Jack knows the reality is to live each moment as it happens. This way disappointments are reduced to a minimum. War is like that. So he focuses on RAF Binbrook which is just visible down below, perched on a hilltop; the hilltop that gave 12 Squadron its nickname ‘Squadron on the Hill’. Great for flying in and out, but not so great for the guys on a pub crawl in Binbrook village, at the foot of the hill, when it is time to stagger back to camp! Having said that, RAF Binbrook is home sweet home at this stage of the war so there is considerable loyalty to its presence, and a tolerance of its shortcomings. It is where they train, eat, sleep and play. And it is where Jack and his crewmates will be expecting to return in about eight hours’ time. Good ole Binbrook. It’s no Monte Carlo, but it’s not a bad place to be stationed. Comfortable quarters. Not bad mess facilities. As well as …‘Jack, keep a look out for Jerry. You, too, Doug,’ crackles the skipper’s voice through their headsets. Both acknowledge.

Their earlier late-afternoon briefing had been interesting. And this being their first active bombing mission over enemy territory, Jack didn’t want to miss a thing. His life might depend on something that at this time could seem quite insignificant, although nobody ever thought he would be the one shot down. The one who might die in a burning plane. It always happened to the other guy.

As Sergeant Jack Newton leaves the crew briefing room, the words of Royal Air Force Binbrook’s station commanding officer still ring in his ears. ‘Your efforts tonight will bloody Hitler’s nose where it will hurt him most. At the heart of his capacity to wage war. Hit hell out of him. Good luck to you all, and get back safely.’ Stirring stuff, and it strikes a very special chord with the impressionable young Newton. It is as though the CO had stuck a picture of Adolf on the sergeants’ mess wall and challenged everyone to pepper it with darts. Only it won’t be a picture of Adolf’s face Jack and his fellow crew members will be peppering in a few hours’ time, it will be his German homeland. The ancient city of Aachen, barely seventeen miles from the Belgian border.

And the crew’s arsenal of ‘darts’ weigh up to 1,000lb apiece, along with a basket of incendiary bombs. Aachen is definitely not a place to be tonight. It also has to be said, this being Newton’s first operational sortie into Germany, it is not one he particularly relishes, although he remains unemotional about the trip ahead. He has already learned to ‘switch off’ his emotions. There is a job to be done. A flight into the unknown for him, and he has very little idea what to expect, other than that it will be a flight into hell. Certainly, it will be very different to the leaflet drops he has been making over the past few months above France and Holland, and the many hours spent on numerous training flights down to Land’s End, over Suffolk and Norfolk, designed to see if his crew can find their way back home. Cheeky! There is no way they will find their way back to Binbrook from Germany tonight if they had got lost on training flights out to Norwich! ‘Anyway, we didn’t, so there is no reason to believe it will be a problem now,’ muses Jack as many thoughts flicker through his adrenaline-pumped mind. Besides, the skipper of their Wellington, with its distinctive registration, is the equally distinctive Flight Lieutenant Roy Brouard Langlois, holder of the Distinguished Flying Cross, awarded to him before the war, though he never told any of his crew for what! He has a DFC, so he’d have earned it for something pretty sensational. Now it is his destiny to lead this new crew of young airmen, to be blooded in the Royal Air Force’s increasingly heavy and effective bombardment! Langlois, his second pilot, Sergeant Pat McLarnon; navigator Harold Burrell (nicknamed ‘Burry’); wireless operator Richard ‘Tich’ Copley; Doug Porteous, usually the front gunner, and Jack Newton, usually the rear gunner, are a great bunch of guys and Langlois is pleased to be with them, as they are happy to have him running the show at the business end of their Wimpy.

Apart from the skipper, the only other member of the crew with previous aerial warfare experience is wireless operator Richard Copley. Born in Farnborough, Hampshire, on 13 October 1919 and educated at the local Famborough Grammar School, Richard was called up on 3 September 1939 and sent straight to Hamble, in Southampton, on a radio operator’s course. He saw action soon after his posting to 12 Squadron in France on 12 May 1940. Over the next month he had logged eleven operational flights, including three during daylight. It was on his twelfth, on 13 June, that he got unlucky in his Fairey Battle. He was shot up by four marauding ME 109 German fighters over the Forêt de Gault, near Paris, as he was bombing Panzer tanks reportedly refuelling under the wooded cover there. The plane caught fire and crashed near St Barthelemy (Seine et-Marne), some twenty miles north of Provine. Of the three crew, Pilot Officer Shorthouse and LAC Copley managed to bail out, but Sergeant Cotterell, the observer, was badly hurt and died in the burning plane. Shorthouse suffered burns, but Copley got off reasonably lightly with a wounded right foot.

In his graphic official report of the incident, Copley said:

Four ME 109 aircraft attacked from the rear in line astern and slightly below. I returned fire, but German tactics were such as to deprive me of any chance of effective gunnery. Our Battle aircraft caught fire, the observer was badly hit. I stayed with him until the altimeter indicated 900 feet, then I realised the pilot had already bailed out. Unable to help the observer in any way, I bailed out. I landed in a field, approximately a quarter of a mile from a German ground gun crew engaging our aircraft, and then realised that my right flying boot was missing and my foot was bleeding badly from bullet wounds. I bound up my foot with emergency dressing and crawled away from the German ground gunners, who had not noticed me. I was picked up by French patrols and taken south to Sens, where I was put aboard a hospital train bound for Bordeaux.

Richard Copley made it safely to the south-west French port of Bordeaux, where he was transferred to a British Indies liner and taken on to Falmouth, in England. In January 1941 he was back at 12 Squadron, but this time flying on Rolls-Royce Merlin-engined Wellingtons. After a number of operational flights across the continent between February and June of that year, on 24 July under the captaincy of Wing Commander Roger Maw, he went on a daylight raid to Brest against the notorious German battleship Scharnhorst, as well as battleships Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen. The crew’s gunners shot down an ME 109. The pilot Wing Commander Maw called it ‘a dicey do’. Anti-aircraft fire was very intense, there was no fighter escort and a considerable number of aircraft and crews were lost in this operation …‘but we made it back to Binbrook in one piece,’ said the skipper, who was awarded a DFC for the crew’s successful part in the operation.

Now, on 5 August it is this fateful bombing raid over Aachen, in the company of skipper Roy Langlois, and three others, McLarnon, Burrell and Porteous, which is occupying front gunner Jack Newton’s thoughts.

Jack recalls his 21st birthday celebration, only last February, in his parents’ home in Townshend Road, St John’s Wood. How he blew out a single candle on the cake made for him so lovingly by his mum, a candle she had rustled up from one of her neighbours. It had been a small and happy family party for Jack, with his fiancée, Mary, by his side to help him through the evening’s low-key celebrations, prior to their marriage in April.