13,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

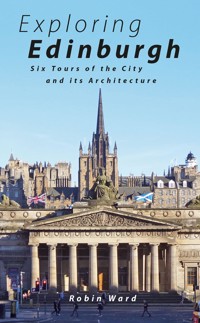

Exploring Edinburgh is an expansive and stylishly formatted guide to the best of Edinburgh's architecture. Not only does it give a brief history of each architectural site but also includes easy to understand maps and suggested walking routes. It also explores locations outside the centre of Edinburgh for those with more time to explore the rich architectural landscape of Scotland's capital.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 251

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Robin Ward is a writer, graphic designer and architecture critic, born and raised in Glasgow. He took a gap year to the Canadian north, as a fur-trading clerk for the Hudson’s Bay Company, and travelled across Canada before returning to Scotland to study at Glasgow School of Art. His interest in architecture was inspired by a high school trip to Basil Spence’s Coventry Cathedral, study at the Mackintosh Building at the GSA and a post-graduate scholarship to Italy. He wrote and illustrated a column for the Herald (Glasgow), worked in London as a designer with the BBC and relocated to Vancouver in 1988. He has travelled widely in Canada, Europe and South-east Asia (he married into a Thai family). For 10 years, he was the architecture critic at The Vancouver Sun. He has received awards for design, illustration and journalism, including a Heritage Canada Achievement Award and a prize in The Architectural Review Centenary Drawing Competition. He is based in Edinburgh.

Other books by this author:

Exploring Glasgow: The Architectural Guide 2017

Exploring Bangkok: An Architectural and Historical Guidebook 2014

Exploring Vancouver: The Architectural Guide (as co-writer) 1993; 2012

Echoes of Empire: Victoria and Its Remarkable Buildings 1996

Robin Ward’s Heritage West Coast 1993

Some City Glasgow 1982; 1988

Office pods for Members of the Scottish Parliament mimic the crowstep gables in the Old Town.

First published in 2021

ISBN 978-1-910022-33-7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset in Myriad Pro by Robin Ward.

Robin Ward’s right to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Text, photographs (except as indicated below) and maps copyright © Robin Ward 2020.

The following copyright © images are reproduced courtesy of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body, entry 3 (aerial photograph); Page\Park Architects, photographer Andrew Lee 128, 265 (Rosslyn Chapel interior); Elder & Cannon Architects 256 (school); Porta Ward 101 (soldier), 102, 110, 111 (lane), 112, 116, 117 (statue), 132, 134, 269.

Contents

Introduction

1 Holyrood & the Old Town

2 Calton Hill, Princes Street & the New Town

3 The West End & Inverleith

4 The South Side

5 Newhaven, Leith & Portobello

6 Out of Town

Acknowledgements, References

The West Front, St Giles’ High Kirk decorated with gargoyles and statues of Scottish monarchs and clergymen. Above the door is St Giles, Edinburgh’s patron saint, with the deer he saved from hunters.

Introduction

Around 1830, St Giles’ High Kirk, Edinburgh’s ‘mother church’, was given a Gothic Revival facelift. Only the 15th-century crown steeple was untouched. In 1884, the west front was rebuilt in medieval style. The kirk’s authentic medieval appearance, weathered over centuries, was wiped away.

Like St Giles’, much of the Old Town is a Victorian fantasy, with buildings designed in the romantic Scots Baronial style. The main street is the Royal Mile – Castlehill, the Lawnmarket, High Street and the Canongate – arrow-straight from Edinburgh Castle to the Stuart dynasty’s palace in Holyrood Park. From 1860 to 1900, two-thirds of the Old Town’s medieval buildings were torn down for slum clearance and civic improvement; only 78 pre-1750 survive. Of 200 or so closes – the shadowy alleys and entrances to tenements – around 80 remain. They branch off perpendicular to the Royal Mile, some precipitous. Many are named after their builders or residents: for example, Advocates’, Brodie’s, Lady Stair’s, or for their commercial links – Fishmarket, Fleshmarket, Sugarhouse. Their medieval pattern is unchanged. Some are said to be haunted.

Old Edinburgh was nicknamed ‘Auld Reekie’, a reference to the stink before modern sanitation was introduced, and smoke from coal fires that once lingered like fog above the tenements. Robert Louis Stevenson described them, in Edinburgh, Picturesque Notes, as ‘smoky beehives, ten stories high’. They were a response to topography: the Old Town tumbles down a steep-sided volcanic ridge on which the only way to accommodate the growing population was to build high.

By the mid 18th century, this dense, overcrowded environment was unsustainable. Lord Provost George Drummond visualised a new town and promoted a design competition for it. The New Town Plan of 1767 showed a rational grid of spacious streets, subsequently lined with Georgian architecture – an alternative, for those who could afford it, to the Old Town where rich and poor scurried around amidst opulence and squalor.

The New Town Plan was a symbol of the Age of Enlightenment, the revival of classical culture in which Scotland played a significant role. More than any other European city, Edinburgh expressed the Enlightenment in architecture. The design of the National Monument (to the fallen of the Napoleonic Wars) on Calton Hill was copied from the Parthenon; the Royal Scottish Academy and the National Gallery on The Mound are also Greek Revival in style. The city acquired a new nickname – the ‘Athens of the North’.

The Old and New Towns are separated by a glacial valley drained of its Nor (North) Loch and landscaped in the 19th century to create Princes Street Gardens, one of the world’s great urban parks. Railway tracks to Waverley Station were laid in the 1840s, hidden from view in a cutting below Castle Rock. The station was named after the Waverley novels of Walter Scott. His monument, a fantastic Gothic pinnacle, punctuates the park. This terrific townscape – Castle Rock, the Old Town, Calton Hill, the New Town and Princes Street Gardens – was declared in 1995 a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Edinburgh’s narrative of enlightenment and cultural heritage ignores many ghosts. Those at Sugarhouse Close are from the slave trade – sugar produced by African slaves on colonial plantations in the West Indies was processed at a refinery in the close. Many of the plantations were owned by Scottish merchants. Glasgow’s complicity in transatlantic slavery is acknowledged. Edinburgh has recently been forced to face up to its involvement.

Slavey in English (later British) colonies gained royal patronage in the 1660s when Charles II granted a charter to (and invested in) what became the Royal African Company. The trade continued until 1807 when the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed. Ownership of slaves was not abolished until 1833, and then only because the British government agreed to compensate not the slaves but their owners. The payout was £20 million (40 percent of the Treasury’s annual budget at the time). Around half of the claimants in Edinburgh gave addresses in the New Town. Profits from plantations and participation in British imperialism bankrolled modern Scotland, but the stain of slavery and its architectural legacy, unlike the medieval fabric of St. Giles’, cannot be easily scrubbed away.

Exploring Edinburgh features the best of the city’s world heritage architecture; also historic sites and buildings in the hinterland where suburbs absorbed rural villages in the 19th and 20th centuries. The book’s six tours are organised for walking, cycling, public transport or car. Entries are numbered and keyed to maps; many are near bus and tram stops. Each tour can be done in a day, longer at leisure. Buildings featured can be entered or viewed from the street. Each entry records the building’s name, location, the architect(s) where known and the date of completion (and start dates where construction was lengthy). Artists, sculptors, structural engineers and landscape designers of interest are noted; also monuments and sculpture, especially in the city centre where, if you look up, 19th-century classical and Renaissance-style statues stare out from façades everywhere.

The World Heritage Site contains some 1,700 buildings of interest listed by Historic Environment Scotland. Exploring Edinburgh is a portable guide, so not all could be included. Those featured have been chosen variously for their social, cultural and political histories, and architectural quality. Modern buildings are noted, but not many because most are unworthy of the city and its World Heritage Site. Some buildings certified BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Methodology), meaning ‘green’, eco-friendly are featured. The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS) and other organisations give annual design awards; some of special interest are mentioned.

Doors Open Days, the annual opportunity to see inside buildings not normally open to the public, are recommended. Some properties are only open in season and not all are mobility-friendly (check their websites). Entries are indexed, not by page but by the entry numbers under which they can be found. The opening page of each tour lists those not to be missed.

—Robin Ward, Edinburgh 2020

The view from Castle Rock

Scotland’s capital city is unique for its layers of historic buildings on a volcanic landscape eroded by an Ice Age glacier. No other city shows its social and topographical development as dramatically. There are panoramas, perspectives and sudden vistas – where turning a corner high up in the medieval Old Town will reveal the New Town, suburbia and the North Sea spread out like a map. An extinct volcano, Arthur’s Seat, looms above everything.

This was the landscape Scottish monarchs beheld until the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when James VI became James I of England and moved the court from Holyrood Palace to London. Scotland’s Parliament was dissolved in 1707 by the Act of Union, creating the British state. Scots lost their independence. Edinburgh became, in the words of poet Edwin Muir, ‘a handsome, empty capital of the past’. The void was partly filled when the Scottish Parliament was revived in 1999. Its members meet in a landmark new building at the foot of the Royal Mile.

1

Holyrood & the Old Town

Holyrood Abbey—Palace of Holyroodhouse—Scottish Parliament—Canongate Tolbooth—Museum of Edinburgh—Moray House—Trinity Apse—The Scotsman Building—St Cecilia’s Hall—Surgeons’ Hall—Old College—National Museum of Scotland—Greyfriars Kirk—George Heriot’s School—Central Library—The Grassmarket—Edinburgh Castle—Scottish National War Memorial—Ramsay Garden—Riddle’s Close—The Writers’ Museum—St Giles’ High Kirk—The Thistle Chapel . . .

1

Holyrood AbbeyPalace of Holyroodhouse, Holyrood Park

Legend has it that King David I, deer-hunting in Holyrood Park, was attacked by a stag. He grabbed its antlers. They were transformed into a crucifix. To give thanks he founded in 1128 the Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood (Holy Cross). It was the most prestigious ecclesiastical structure in Scotland (twice the length of the ruin today). Excavations in 1911 proved the nave had been extended with a choir and north transept, and towers flanked the west door.

During the Wars of Independence, the abbey was looted by Edward II’s army. In 1385, it was set ablaze – along with Holyrood Palace and the town – by Richard II, and desecrated again by the English in 1540s. The monastic regime was ousted during the Protestant Reformation of 1560. The grounds remained a sanctuary for debtors – cobblestones on Abbey Strand show where the boundary was; the crowstep-gabled building here (c. 1500) was an almshouse, originally perhaps the abbot’s dwelling.

In 1633, the partly ruined abbey was repaired for the Scottish coronation of Charles I (the traceried east gable is from that time). James VII, the last Stuart monarch, made the nave the Chapel Royal, before he fled to exile in France in 1688. In 1758, it was roofed with stone slabs which collapsed ten years later. The wreckage was abandoned to erosion and decay, Victorian artists and writers were drawn to its sublime quality. It remains as they saw it.

2

Palace of HolyroodhouseHorse Wynd, Holyrood Park

16th century; William Bruce ‘Surveyor-general and overseer of the King’s Buildings in Scotland’ & Robert Mylne ‘King’s Master Mason’ 1671–8

The official residence in Scotland of the reigning British monarch, who visits annually. Honours are granted. There is a garden party. But behind the ceremony and decorum there is a dark and bloody history.

Construction was started by James IV. James V added the double-barrelled North-west Tower, styled like a Loire château. It survived when Edinburgh was attacked by the English in the 1540s – the ‘rough wooing’, an attempt by Henry VIII to have his son Edward marry Mary Queen of Scots. She is the most romantic and ill-fated royal associated with Holyrood. It was here, in her apartments in the Northwest Tower in 1566, that her private secretary David Rizzio was stabbed to death by assassins. A stain on the floor is said to be his blood.

In 1603, James VI became James I of England and took the Royal Court to London. The palace was revived by Charles II, who rebuilt it copying James V’s tower to create a symmetrical west front. Its monumental Roman Doric gateway leads to a Renaissance-style courtyard. During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Bonnie Prince Charlie held court here. George IV, who visited the palace in 1822, ordered it be repaired and Queen Mary’s apartments ‘preserved sacred from every alteration’. King George is still here, dressed as a Highland chieftain in a portrait by David Wilkie in the Royal Dining Room. In the Long Gallery are portraits of Scottish monarchs, commissioned by Charles II.

The fountain in the forecourt is a Victorian replica of James V’s original at Linlithgow Palace. The ornate gates (c. 1920), were part of a memorial to Edward VII, a statue of whom is in the forecourt. On Horse Wynd (the royal stables were here) is the Queen’s Gallery (Benjamin Tindall Architects), a Victorian church and school converted to celebrate the Queen’s Golden Jubilee 2002 and to exhibit artworks from the Royal Collection.

3

Scottish ParliamentCanongate and Horse Wynd

Enric Miralles & Benedetta Tagliabue (EMBT), RMJM architects, Arup engineers 2001–4

Scotland’s old parliament ‘voted itself out of existence’ in 1707 when the Act of Union established the British Parliament in London. Repatriation of the Scottish Parliament was approved by referendum in 1997. An architectural competition was held, won by Barcelona-based EMBT. So loaded with political and cultural ambitions was the enterprise that it became as contentious as the dissolution almost three centuries before. Costs and criticism spiralled as the design evolved, but it was a masterpiece in the making. Architect Enric Miralles died before it was done.

The organic plan (seen in this aerial image) grows out of the Old Town – a ‘dialogue across time’ Miralles said. Leaf and boat shapes symbolise the land and sea of Scotland (the leaf motif inspired by the flower paintings of Charles Rennie Mackintosh). Spatial magic inside owes much to Antoni Gaudí. The office pods on the members’ (MSP) block were conceived as ‘monks’ cells’, to encourage the politicians to think. Queensberry House, a 17th-century mansion on the Canongate, was incorporated. Also on Canongate, the Canongate Wall, a concrete bulwark decorated with a collage of poetic quotations and stones from across the nation, and a sketch by Miralles of the Old Town.

The Debating Chamber is a luminous elliptical space under steel and glulam (glue-laminated) oak trusses, which recall the 17th-century roof of Old Parliament Hall (see entry 68). Craftsmanship and detailing throughout the building are exceptionally refined. Timber, concrete, steel and granite are the primary materials. The complex is sustainable, low-energy, rated BREEAM Excellent. There are green roofs and bee hives (the beeswax is used for official seals). The landscape, biodiverse with native plants and flowers, blends with historic Holyrood Park. Above all, the architecture dignifies parliament’s purpose.

In 2005, the building won the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Stirling Prize and the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS) Andrew Doolan Award, respectively the top UK and Scottish architectural prizes.

4

Dynamic EarthHolyrood Road at Holyrood Gait

Michael Hopkins & Partners 1999

Fabric-skinned pavilion looking like some prehistoric creature, lodged in the shell of a 19th-century brewery on the edge of Holyrood Park. The brewery walls, visible from Queen’s Drive, were disguised as a castle to please Queen Victoria.

Dynamic Earth’s style is High Tech, with the roof cable-stayed from steel pylons. Inside are exhibits about the evolution of Planet Earth. James Hutton, ‘the founder of modern geology’, lived nearby. Directly south are volcanic features that inspired him, Salisbury Crags and Arthur’s Seat.

5

White Horse Close27 Canongate

Looks like a film set but the buildings are real, restored in the 1960s (Frank Mears & Partners architects). The authors of The Buildings of Scotland judged this ‘so blatantly fake that it can be acquitted of any intention to deceive.’ The picturesque 17th-century form and style – forestairs, harled walls, crowstep gables and pantiled roofs – replicated Victorian reconstruction (c. 1890) for workers’ housing by the Edinburgh Social Union, a philanthropic society created by Patrick Geddes (see 58).

The close was once famous for the White Horse Inn, a departure point for stagecoaches to London. During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Bonnie Prince Charlie’s officers lodged here when the prince occupied the Palace of Holyroodhouse. The name refers to a white palfrey (a docile horse) said to have been the mount, stabled here, of Mary Queen of Scots.

6

Adam Smith’s Panmure House4 Lochend Close, Canongate

1691; EKJN Architects 2018

Built when the Canongate was a rural, aristocratic suburb of the Old Town. The name recalls the Earl of Panmure, a Jacobite who forfeited the property to the British state after the failed rising of 1715. In 1778, Adam Smith, author of The Wealth of Nations, moved in with his mother, cousin and nephew, and 3,000 books. Among those drawn to Smith’s ‘salons’ were architect Robert Adam, chemist Joseph Black, geologist James Hutton and philosopher Dugald Stewart. Their spirit of enquiry inspired the restoration of the house by Heriot-Watt University as a forum for global economic and social debate.

7

Scottish Poetry Library5 Crichton’s Close, Canongate

Malcolm Fraser Architects 1999; Nicoll Russell Studios 2015

This was an award-winning building of exceptional clarity in an alley of mixed-up buildings (tenements, an old brewery). Outdoor steps, like a medieval forestair, were used as seats for poetry readings, an informal interface with the public realm. Unfortunately this liberating feature was lost when the interior was enlarged by pushing the ground floor out to the property line.

8

112 Canongate

Richard Murphy Architects 1999

A Saltire Society Housing Design Award winner in 2000, designed for the Old Town Housing Association. Timber siding and harled walls evoke the past, along with upper rooms cantilevered from the façade to gain floor space, a form (see 17) familiar to residents of medieval Edinburgh. Script on the steel beam, ‘A nation is forged in the hearth of poetry’, alludes to instructive texts found on Old Town architecture (see 12) and to the Scottish Poetry Library down the close.

Across the street is Dunbar’s Close Garden (Seamus Filor landscape design 1977). It was inspired by Patrick Geddes who advocated green spaces to bring nature to the Old Town’s cramped closes where most people lived. The garden was donated by the Mushroom Trust to the city in 1978.

9

Canongate Kirk153 Canongate

James Smith 1688–91

‘Canongate’ refers not to a gate, but gait, from the Norse word for ‘street’, where walked the canons of Holyrood Abbey. James VII ordered the kirk to be built for the congregation he evicted from the abbey, which he wanted for the Order of the Thistle (see 66). Funds were from monies left by merchant Thomas Moodie, noted on the façade which boasts a huge Dutch gable and Roman Doric porch. The heraldry above the rose window represents William of Orange who took the British throne from James VII in 1688. The antlers on top of the gable recall the legend of King David’s founding of Holyrood Abbey. The interior is festooned with royal and regimental banners and flags (this is the Kirk of Holyroodhouse and Edinburgh Castle).

10

Canongate Tolbooth163 Canongate

Built in 1591, this was the town hall, court house and jail of the old Burgh of Canongate which was absorbed by Edinburgh in 1856. The style is Franco-Scottish – the architecture of the Auld Alliance (see 63). The forestair from the street led to the council chamber and court room. The jail was in the tower. The old burgh’s Market (Mercat) Cross is in Canongate Kirkyard. Notable citizens buried here include Adam Smith and the prophet of the New Town, six-time Lord Provost George Drummond.

On the Tolbooth’s façade is the burgh’s coat of arms, dated 1128 when David I established Holyrood Abbey; also the stag that caused him to build it. Inscriptions in Latin read, ‘Justice, piety, truth; thus is the way to the stars’ and ‘For Native Land and Posterity 1591.’ Star and thistle finials appear above the Victorian attic windows; the clock on wrought iron brackets was installed in 1884; the tavern was established in 1820. The Tolbooth houses Edinburgh Museums’ exhibition, The People’s Story.

11

Robert Fergusson statueCanongate

Robert Annand sculptor 2004

Competition-winning effigy of poet Fergusson, striding past Canongate Kirk. He died young in the city’s Bedlam in 1774, alone except for his demons, and was buried in the kirkyard in an unmarked grave. Robert Burns, for whom Fergusson was an inspiration, found it ‘unnoticed and unknown’ in 1787 and paid for a headstone inscribed with an elegy he composed.

12

Museum of Edinburgh140–146 Canongate

‘The city’s treasure box’ is housed in several buildings, principally the gabled Huntly House, originally three adjoining timber structures, rebuilt in stone in 1570. The Latin inscriptions on the façade lent it a nickname, ‘the talking house’. There were several successive owners, and a tenuous association with the Marquess of Huntly. The house was bought by the city in 1924 and restored as a museum (Frank Mears architect 1932). Its collection is illuminating, extensive and eccentric. An upgrade, reconfiguration and redisplay (Benjamin Tindall Architects 2012) emphasised its serendipity.

Huntly House, Canongate Kirk and the Tolbooth form the largest cluster of 16th- and 17th-century urban buildings in Scotland. Among them is Acheson House in Bakehouse Close (146 Canongate). The close evokes the past so well that location scouts for Outlander found it needed little dressing as a backdrop for the TV show’s Jacobite setting. The original owner of the house was Archibald Acheson, a government minister for Charles I. In the courtyard is the Acheson crest (1633) – cockerel, trumpet, the motto ‘Vigilantibus’, meaning ‘forever watchful’, and a monogram with the initials of Archibald Acheson and his wife Margaret Hamilton.

In the 19th century, Bakehouse Close was a densely populated slum. At that time, Acheson House was a tenement and brothel, having been bought and sold several times, each transaction leading to decline. In 1924, it was bought by the city, sold to the 4th Marquess of Bute in 1935 and restored (Robert Hurd architect). Based here is Edinburgh World Heritage, for which the historic house was adapted (Benjamin Tindall Architects 2012).

13

Sugarhouse Close154–166 Canongate, 41 Holyrood Road

18th century; rebuilt 1860s; Oberlanders Architects, Will Rudd Davidson engineers 2011–14

The name sounds sweet but hides the bitter taste of Scotland’s role in the slave trade. The Edinburgh Sugar House Company opened a refinery here in 1752 (there were other refineries at the Port of Leith). The raw material came from plantations worked by African slaves in the West Indies. From 1829 to 1852, the refinery was owned by William Macfie & Co., the sugar dynasty established in 1788 at Greenock (Port Glasgow). Above the pend is a panel with the Clan Macfie lion rampant and motto ‘Pro Rege’, meaning ‘For the King’.

When the site was redeveloped as a brewery in the 1860s, the Macfie panel, the two-storey oriel window in which it is set, and the crowstep gable with a star finial were evidently retained. Remains of the brewery have been blended into ‘Sugarhouse Close’, student accommodation expressed in varied built forms sympathetic in scale, materials and linear plan to the historic setting.

14

Moray House174 Canongate

William Wallace master mason c. 1625

The finest of old Canongate’s aristocratic townhouses, designed for the Countess of Home whose coat of arms is above the corbelled balcony on Canongate. In 1643, the house was inherited by her daughter, the Countess of Moray. It bristles with chimneys, crowstep gables and wrought iron gates with spiky pillars. Inside are original plaster ceilings and painted decoration. In 1848, Moray House became a school; later a college of education, absorbed by the University of Edinburgh in 1998.

The much-diminished garden originally extended to what is now Holyrood Road. Its Summer House has acquired notoriety. According to tradition, it was where the ‘false and corrupted statesmen’ who signed the 1707 Act of Union with England ‘were obliged to hold their meetings in secret, lest they should have been assaulted by the rabble’ [of protesters]. So wrote Walter Scott in Tales of a Grandfather. Most Scots opposed the treaty but they had no vote. Robert Burns, in a poem of 1791, wrote that those who signed it had been bribed and the nation ‘sold for English gold’.

15

Bible Land183–187 Canongate

1677

Tenement built for the Incorporation of Cordiners (shoemakers) of Canongate (‘cordiner’ from the French courdouanier meaning ‘of Cordova’, from where was imported the finest leather of the time). The cartouche above the door is finely decorated with carved cherub heads, the Green Man, a crown, a cordiner’s leather-cutting knife, and an open book with an inscription from Psalm 133, hence ‘Bible Land’. Another cordiners’ plaque (1725) can been seen on Shoemakers’ Land (195–197 Canongate).

These buildings, refurbished recently by Edinburgh World Heritage, are among several Canongate tenements reconstructed (Robert Hurd & Partners 1953–64). They include Morocco Land (265 Canongate). The figure of a Moor on its wall is said to recall fugitive Andrew Gray, sentenced to death for treason after the coronation of Charles I in 1633. He escaped to the Barbary Coast where he gained favour and wealth with the Sultan of Morocco. In 1645, Gray with a crew of corsairs sailed back to Edinburgh and threatened to sack the city. He secured a pardon by curing the Lord Provost’s daughter of the plague, married her and settled here.

16

Tweeddale Court14 High Street

Sixteenth-century courtyard, once the property of the Marquess of Tweeddale. It was a crime scene in 1806, when a British Linen Bank messenger was murdered and robbed of £4,000. The killer was not caught. The bank’s building, Tweeddale House, is still here, complete with an Ioniccolumned doorway. The name Oliver & Boyd above it recalls Edinburgh’s distinguished history of printing and publishing.

Also in the courtyard is a fragment of the King’s Wall, a fortification built by James II. Attached to it is the city’s smallest heritage-listed building, an 18th-century lean-to used for storing sedan chairs on which the well-to-do could be carried so as not to set foot on the Old Town’s filthy streets.

17

John Knox House43–45 High Street

1470; enlarged c. 1560

John Knox is said to have lived here, an association which saved the house from demolition in the 19th century. In the 16th century, it was the home of Mariota Arres whose husband, James Mossman, was goldsmith to Mary Queen of Scots. Their initials are visible outside, along with a figure (Moses, not Knox), a sundial and a carved inscription ‘Luve God abuve al and yi nychtbour as yi self.’ Mossman’s loyalty to the queen led to his execution in 1573.

Next door is Moubray House, mostly 17th century (earliest record 1477) with a forestair and overhanging gable, features once common. It was restored in 1910 by the Cockburn Association, which has an office in the cellars. Lord Henry Cockburn campaigned to prevent the Knox House being torn down. His spirit lives on in the association named after him. On the street outside is Netherbow Wellhead (William Bruce & Robert Mylne 1675).

The Knox House, a museum since 1853, is accessed from inside the Scottish Storytelling Centre (Malcolm Fraser Architects, Elliott & Company engineers 2006), the world’s first purpose built national centre for storytelling. On the wall is a plaque with the legend ‘1606, God save the King.’ This is a relic of Netherbow Port, the most impressive of the Old Town’s six gates. It was demolished in 1764 because it was too narrow for the increase in ‘wheeled carriages’ and pedestrian traffic. How it looked can be seen on a panel on the façade of the adjacent Victorian tenement. The clock from its tower was salvaged and later fitted to Dean Orphanage (see 135). Its bell, cast in the Netherlands in 1621, is housed in the Storytelling Centre’s tower.

18

Heave Awa’ HousePaisley Close, 101 High Street

John Rhind sculptor 1862

One night in 1861, a 16th-century tenement here collapsed, killing 35 of the 77 residents. In the pile of rubble the next morning, a boy’s voice was heard by rescuers, ‘Heave awa’ lads, ah’m no’ deid yet’. When the close was rebuilt, his release was honoured. His face, serene considering how he got here, is on the keystone. The tragedy and the hazardous condition of other tenements led to the City Improvement Act of 1867.

19

Trinity ApseChalmers Close

1462; reconstructed 1877

Trinity College Kirk was a unique relic of medieval Edinburgh. The North British Railway Company bought its site from the city to build Waverley Station and, in 1848, the kirk was dismantled – ‘scandalous desecration’, Henry Cockburn thundered. Its stones were numbered and stored for re-erection, to be paid for by the NBR.

Proposals to rebuild it on Calton Hill, Castle Rock or in Princes Street Gardens came and went. Other builders helped themselves to the stockpile, leaving ‘a medieval jigsaw puzzle’. In 1877, the remaining stones were used to reconstruct the apse, attached to a new church at the foot of Chalmers Close. When that church was demolished in 1964, the apse was spared. It remains a wonder of medieval masons’ craft, lofty and fan-vaulted. Numbered stones can be still be spotted. The south wall faces a garden where a few stones not re-erected are scattered – gargoyles, a monster’s feet, the Green Man.

A 15th-century altarpiece painted by Hugo van der Goes for the original kirk is in the National Gallery.

20

Old St Paul’s Scottish Episcopal ChurchJeffrey Street and Carruber’s Close

Hay & Henderson 1883