Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

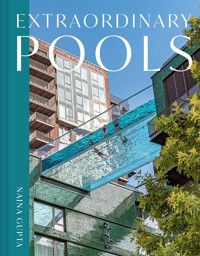

A visual feast of 49 weird, wonderful and architecturally astounding swimming pools from around the world. This book is a sumptuous celebration of swimming pools as playgrounds of pioneering design and architectural excess. Banish memories of crowded leisure centres and sun lounger-clad lidos, these are pools designed for pleasure, not purpose. Swimming pools are no longer simply places to swim, they are versatile sites of activity and excess. They can be vital lifelines providing communities with safe access to water, domestic symbols of affluence, and the avant-garde spectacle of hotel developers. Naina Gupta uncovers some of the most spectacular swimming pools from around the world, including Berthold Lubetkin's modernist Penguin Pool at London Zoo, the world's largest infinity pool at Marina Bay Sands, Ricardo Bofill's blood-red garden pool in Spain, and London's unparalleled Sky Pool. Extraordinary Pools also includes 4 extended essays on various aspects of pool culture, such as the use of empty swimming pools in California by skateboarders. Illustrated throughout with awe-inspiring colour photography, Extraordinary Pools is a mosaic of exceptional public and private pools, reasserting the protean quality of the swimming pool as a space of activity, pleasure and excess.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 158

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Phantom Pools, Naina Gupta

1. Progressive Visions

2. A Matter of National Importance

Mussolini’s Boys:Muscles, Messages and Mosaics

3. A Pool with a View

Deep Diving:Half Air, Half Water, A Fantasy

4. A Very Private Affair

5. ‘Natural’ Pools

6. Free Form, Free From

Concrete, Tiles and Coping:How Skateboarders Fell in Lovewith the Swimming Pool

7. Pool Culture

8. In Suspension

Domestic Monument

Where to find the pools

Index

Further reading

Acknowledgements

Picture credits

Phantom Pools

Naina Gupta

The architectural historian Thomas van Leeuwen observes that swimming is possibly the closest a human being will come to experiencing the sensation of flying. Swimming is a learned movement – it is different from what we consider our natural stance to be. Therefore, the question then arises: how does swimming inform the design of the space and in turn, how does the space enable and enrich this way of moving? What is the role of architecture in swimming pools? The projects that have been profiled in this book have in different ways contributed to these questions. Swimming allows one to move in ways that are simply not possible on land. Moving in water – skimming or floating on the surface; suspended in it with a ‘frog’s-eye’ viewpoint of the world; penetrating it as one dives in; or piercing through it underwater – at the least fosters new ways of exploring space physically, visually and textually. The potential that it opens is what I believe makes for extraordinary pools in architecture. Even after being contained, water is anything but predictable. The nature of water as a material, as an effect and as an inhabitable space, fires the architectural imagination where reflection, transparency, fluidity and immersion continually birth new ways of interacting with the space. In this introduction, I am going to talk about the relationship between the swimmer and the architecture of the pool, using examples of some of the pools – real and imagined – that exert their presence phantom-limb-like on the architectural history of swimming pools.

On the surface, a pool is a deceptively simple object – a shaped hole in the ground. One of the more legendary swimming pools in architecture was exactly this – a circular hole in the ground that was an afterthought. In 1937, Moscow announced Boris Iofan’s winning design for the towering Palace of the Soviets. Construction stopped in 1941 and did not resume after the war. Instead, in 1958, the 130m (426ft) diameter hole was filled with water, creating a sport and recreation destination simply called the Moskva Pool. The pool was divided into wedges that were segregated by sex. An Olympic set-up graced its centre, which included a soaring A-shaped diving structure that framed views across the diameter, most likely axially with the bridge across the river. There are just enough people outside the Soviet Union who have swum in this pool to help to keep its mythical status intact. One of the beautiful stories I heard was about a swim enveloped in rising steam and falling snow in the bitter Moscow winter. Today, the pool has been replaced by the Christ the Saviour Cathedral.

Beneath their shadowy depths, swimming pools conceal a powerful space of imagination where spatial, socio-political, physiological and psychological constructs are being continually constituted and challenged. Where does a pool begin? Is it at the surface of the water or the edge of the basin? Or perhaps it begins at the point where one gets the faint but distinctive whiff of chlorine? The key elements that constitute a pool include the basin, the changing rooms, diving structures, ladders and, to a lesser extent, depending on the type of pool, tiled surfaces, the black line and a clock. This already rich palette is compounded by minute, even invisible, textural qualities that incessantly calibrate the way that our body moves and perceives space. The near-naked swimmer’s skin is in direct contact with and sensitive to materials, temperature, vibrations, colour, sound and smell – all of which are intertwined, leading to a feeling that every pool is unique, and every swim is slightly different. Swimmers have favourite pools and pools that they do not return to. Some swimmers swim only in ‘their’ pool, content with the novelty that each day brings. For others, pool hunting and all the physiological and psychological response that it incites is part of their swim make-up. Most swimmers lie in between those two extremes. Then there is the category of the non-swimmer pool hunters – the Insta swimmers – who play an equally important role in swimming pool architecture: they motivate innovation and, inadvertently, support architecture.

There is an almost childlike sense of wonder and exploration in swimming – the colours of sunrise and sunset on water, swimming in the moonlight, looking a duck in the eye or hovering above a city – which provokes an equally playful response in the architect/artist, where small inclusions, changes, tweaks and innovations build upon known experiences to create new ones, which in turn are complemented by material advancement and technical expertise. The richness of the palette – materially, experientially and as a social project – is an essential part of the fantasy of designing a swimming pool.

An empty pool is a sad object. Of course, one cannot swim without water, but it is more than that. What is a pool without water? It is surely not a hole. A hole implies that it can be filled, though there have been many attempts to fill an empty pool with other functions; however, its emptiness shadows everything else that is there, except in the rare example, when it births something else such as skateboarding or, perhaps, ice skating. Water gives a pool a function, it gives it colour, and it brings the composition together. Moreover, it gives it a scale – the tiles in a pool are scaled in consideration of a swimmer’s speed, gaze and body. Water connects and separates a pool from nature. Azure, the infamous abandoned pool deep in the heart of the nuclear disaster zone in Pripyat in Chernobyl (pictured opposite) was potentially an extraordinary pool. Its yawning jaw-like concrete building opened the swimming hall to natural light and vegetation. Twelve years after the disaster, the pool was finally abandoned when the liquidators left the site – a void in the fabric of the world symbolized by the void of the pool that is slowly being overtaken by nature.

In plan, swimming pools are organized as concentric rings with numerous one-way paths designed to keep ideas of cleanliness and social propriety intact. The architecture marks a sequence of movement, space and behaviour – dry to wet, clothed to swim-suited, closed to open – that is reversed as one leaves the space. The centrality of the pool encourages seeing and being seen, which over the decades has included portholes pierced below the waterline or completely glass-fronted pools that instantly transform the swimmer into a mythologized Mer-person. In 1925, Adolf Loos met Josephine Baker in Paris and, unsolicited, drew up a plan of his fantasy house for her. The house is pierced by a double-height, top-lit pool that is surrounded by low passages fitted with glazed panels through which a spectator (he) might catch a glimpse of Baker as she glides past in the water. There is the play of exhibitionism-voyeurism in the design that Loos assumed that Baker would willingly partake in.

There is something intimate and vulnerable about immersing oneself in a shared body of water that does not translate quite the same way in most other spaces. Therefore, pools are spaces with some of the more problematic segregationist policies related to gender and race, which in turn is what makes them vital as they unveil unresolved conflict, forcing society to reconsider its outdated and unhelpful norms. Otto Koenigsberger, a Jewish-German émigré to India, designed a municipal pool in Bangalore in 1940. It was one of his first projects in the country. It is a simple, functional project that is a scaled down version of the lidos that were built in England in the 1930s. There is very little mention of this building in his portfolio, and few images of the project survive in his archives, though he did write to his mother about it; nonetheless, the legacy of this pool in the city cannot be overstated. Housed in the heart of the city close to Cubbon Park, the pool was in use until the 1990s, after which it was demolished. Interestingly, Bangalore is peppered with municipal pools, which is not typical for an Indian city. Now, while the relationship between Koenigsberger’s pool and the swimming culture in the city cannot be ascertained, nevertheless, concluding that there is a connection between the two is surely within reason. Koenigsberger’s pool was most likely designed as the counterpart to the pools in the many clubs in the city. While the club pools were meant for the people of the empire and, in the words of Salman Rushdie, the ‘better sort of Indian’, Koenigsberger’s municipal pool was meant for the people of the colony.

Social ideas about comfort, disease, safety and ecology are often at odds with each other and contribute to the early demise of the building – pools have notoriously short life spans. Chlorine and condensation eat at the structure; sunscreen plays havoc with the mechanical and biological filtration systems of pools. To boot, diving structures are increasingly being decommissioned in public pools, limiting diving to a spectator sport. The architecture of diving was a space ripe for experimentation that was intimately connected to the development of the skill. Compositionally, its verticality balances the horizontality of the surface of water, creating a volumetric reading of the pool. Its only role is to support a series of platforms at different heights from which people could spring off into the water below. The variations are infinite – a structural and aesthetic problem waiting to be solved. Springboards still feature in pools deep enough for them, but pools are increasingly becoming shallow, in many ways. In a few decades, we are possibly going to be seeing a generation of swimmers who have never catapulted themselves cannonball-like into a pool or belly flopped painfully on its surface – thereby, learning an invaluable lesson.

Rem Koolhaas and Madelon Vriesendorp were living in New York in the 1970s when they wrote ‘The Story of the Pool’ (1976). The young couple had a bulletin board populated with postcards of swimming pools. It is likely that many of the pools on that board, built in the 1930s as part of the New Deal, were closing or were in a deplorable condition. In the story, the floating pool in its ‘ruthless simplicity’ represents the remaining vestige of radical vision in architecture, which by the end of the story suffers a fatal end.

1

PROGRESSIVE VISIONS

Badeanstalten Spanien

Spanien 1,8000 Aarhus,Denmark

The ‘Spanien’ was designed by city architect Frederik Draiby in 1933 in the then novel Nordic Functionalist style (funkis). Spanien was then one of the four swimming pools in the country, and was equipped with state-of-the-art technology that included purified salt water in the pool, an artificial rain shower above the pool that was fragranced with the smell of pines, and a solarium, to mention a few. It has been renovated twice in the last decade to modernize its facilities; nevertheless, it retains its 1930s charm.

Externally it is a four-storey unadorned brick building that is divided into two wings on either side of a water tower, which is embellished with a neon sign that is integrated into the façade – a signal of modernity when electricity was new. While the bathing wing is punctuated with square windows, the swimming hall on the other hand has vertical fenestrations that fill its cavernous volume with daylight. A gallery divides the hall vertically into two halves. The lower half is painted green, which continues as tiles cladding the swimming basin. The upper half is painted yellow, which changes into a deep blue on the ceiling, complementing the pool below. The bright contrasting colours liven the otherwise stark interiors.

In the 1930s, the gallery led to a diving board that sat in front of the windows silhouetting the divers; however, today it has been replaced by a viewing deck that juts out over the pool, creating the feeling of standing at the bow of a ship. A circular copper clock with disks that mark the hours adorns the wall opposite the viewing deck. This circular motif is repeated in the porthole windows pierced in the copper-clad room on the top floor of the water tower that looks upon the rapidly changing gritty industrial city and its harbour.

Spanien is a listed building and a treat for both architecture and swim lovers.

The Berkeley City Club Pool

Berkeley City Club,2315 Durant Avenue,Berkeley,CA 94704,USA

In 1929 Julia Morgan was commissioned to design the Women’s City Club in Berkeley, which opened its doors to men for the first time in the 1960s when it rebranded itself as the Berkeley City Club. The pool is a Morgan ‘original’ that is open to members and hotel guests. Phoebe Appleton Hearst’s early support of Morgan’s architecture fostered two diverging interests that occupied Morgan for the most part of her active career – William Randolph Hearst’s fantasy projects, and the YWCAs, women’s clubs and community projects along the west coast. The club was one of the few places where a woman could access a swimming membership that spanned the entire year in the early 20th century.

Morgan was intimately involved in the design of every aspect of the pool, including the seahorses on the capitals of the columns, the hanging light fixtures for late evening swims (these have now been moved to the tearoom above) and the skylights that animated the water surface when open. The pool, or the ‘plunge’ as she called it, comprised the entire east wing of the building and is wedged between the east court and the garden, allowing for ample morning light to wash the space through the triple arched windows, which are fitted with leaded glass. Morgan’s maturity as a designer is realized in the use of the water surface as part of the formal articulation of the space. A vaulted ceiling dominates the central axis of the room, terminating in a recessed spectator gallery. The concrete beams between the arches are painted a turquoise blue to match the tiles in the pool and are mirrored on the floor of the pool as yellow lines, enhancing the depth of the reflection of the vaulted ceiling on the water surface. The yellow and blue are repeated in the chevron pattern on the skirting that runs around the room and on the edges of the arches, allowing every line and surface to be clearly articulated even as it comes together as a united whole.

The symmetry of the space along multiple planes earned the pool an entry on the social media platform Accidentally Wes Anderson.

Piscine Pontoise

Piscine Pontoise,19 rue de Pontoise,75005 Paris,France

The Piscine Pontoise was designed by Lucien Pollet in 1934 and is part of a series of swimming pools that he designed for La Société des Piscines de France, which includes the Molitor that was completed a few years before the Pontoise. Pollet’s pools evoke images of ocean liners or, more historically, 18th-century floating baths that populated the Seine. The pool is housed in an intricate Art Deco brick building in the Latin quarter on the rue de Pontoise, just off the Boulevard Saint-Germain. It is one of the many jewels in this quarter that is rich with other treasures such as the Panthéon, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, the Sorbonne University and Musée de Cluny.

On entering the building, one leaves the bustling streets of the fifth arrondissement behind to immerse oneself in the swimming culture of the 1930s. In lieu of communal changing rooms, the pool is circumscribed with overhanging galleries lined with individual changing cubicles with cerulean blue doors. The blue and white nautical colour palette distinguishes Pontoise from the other Parisian pools of the era. The wrought-iron railing along the gallery echoes a subtle Art Deco pattern and is painted a darker blue that matches the band of blue-gold mosaic that runs horizontally along the gallery edge. The pool is open until midnight on weekdays and the experience of swimming in the day is diametrically different from swimming at night. In the day the 33m (108ft) long pool is washed with diffused natural light from the translucent glass roof. At night, on the other hand, the light appears to emanate from the water, which renders the hall in an ultramarine glow.

It is a blue pool, which arguably made it the ideal setting for Juliette Binoche’s nightly swims in the film Three Colours: Blue, directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski.

The pool was restored for the Paris Olympics in 2024, and is due to be reopened to the public.

Parliament Hill Fields Lido

Parliament Hill Lido,Gordon House Road,London, NW5 1LT,England

Parliament Hill Fields Lido, completed in 1938, was designed by Harry Rowbotham and T.L. Smithson, who were responsible for several LCC lidos that were built between 1906 and 1939, including Brockwell Lido and London Fields Lido. Their signature tiered fountain that was used for aerating the pool water can be seen in all these lidos, even if today they are purely ornamental and sometimes not even used. A simple brick perimeter separates the lido from the heath and contains all the functions within its depth, leaving a large open space in the centre for the pool and sundecks.

The pool is approximately 60m x 27m (200ft x 90ft). In 2005, it was refurbished to include a stunning stainless-steel cladding on the pool basin with an articulated edge detail that sits on top of the concrete, and in the summer is a welcome transition from the warm concrete pool deck into the cooler waters. During the refurbishment the depth of the lido was reduced from 2.75m (9ft) and now is only 2m (6½ft) deep at the deepest end, with a shallow end of 1m (3ft) or so for at least half of its length. This allows it to function more like an urban seascape – catering to a spectrum of people with different needs, who range from water walkers to children to lap swimmers. The star of this lido is its highly photogenic stainless-steel basin, which reflects the temperamental British weather, colouring the water in a gun-metal grey on a cloudy day or an electric metallic blue on a sunny one – hues that are unique to this pool. Swimming in these colours makes one feel like one is flying, sandwiched between layers of the blue sky. The steel contributes to the auditory experience of swimming, as one can feel its vibrations as the tumble-turners hit off the edge, especially in the shallower end, which in itself is a remarkable feat.