Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

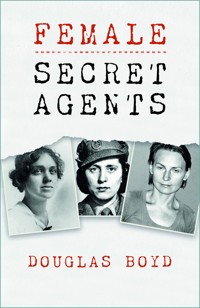

Forget the adventure stories of James Bond, Kim Philby, Klaus Fuchs and co. – espionage is not just a boys' game. As long as there has been conflict, there have been female agents behind the scenes. In Belgium and northern France in 1914–18 there were several thousand women actively working against the Kaiser's forces occupying their homelands. In the Second World War, women of many nations opposed the Nazis, risking the firing squad or decapitation by axe or guillotine. Yet, many of those women did not have the right to vote for a government or even open a bank account. So why did they do it? Female Secret Agents explores the lives and the motivations of the women of many races and social classes who have risked their lives as secret agents, and celebrates their intelligence, strength and courage.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Douglas Boyd

Histories:

April Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine

Voices from the Dark Years

The French Foreign Legion

The Kremlin Conspiracy: 1,000 Years of Russian Expansionism

Normandy in the Time of Darkness:Life and Death in the Channel Ports 1940–45

Blood in the Snow, Blood on the Grass:Treachery and Massacre, France 1944

De Gaulle: The Man who Defied Six US Presidents

Lionheart: The True Story of England’s Crusader King

The Other First World War: The Blood-SoakedRussian Fronts 1914–22

Daughters of the KGB: Moscow’s Cold War Spies,Sleepers and Assassins

Novels:

The Eagle and the Snake

The Honour and the Glory

The Truth and the Lies

The Virgin and the Fool

The Fiddler and the Ferret

The Spirit and the Flesh

Cover images, from left: secret aents Agnes Smedley, Andrée Borrel and Cynthia Murphy.

First published 2016 as Agente: Female Secret Agents in World Wars, Cold Wars and Civil Wars

This paperback edition published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Douglas Boyd, 2016, 2023

The right of Douglas Boyd to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75096 953 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

1 The Perfect Cover for the Perfect Spy

2 Handmaidens of the Red God

3 Born in Bessarabia, Buried in Beijing

4 The Women Who Did Not Talk About It

5 Women Against Hitler

6 The Human Submarines

7 When the Men are Away …

8 SOE SOS

9 Heroine or Liar?

10 Rape as a Tool of War

11 The Whore of the Republic

12 Sayonara, SIS

13 Two Daughters of Israel

14 The Pearl in the Lebanese Oyster

15 Dutch Courage

16 Condemned for Mercy

17 Death Behind Bars

18 Women in the Cold War

19 Women in the War Between the States

20 ‘Intrigues Best Carried On by Ladies’

21 Strange Ladies Indeed

22 Sex and the Secretary of State

23 The KGB is Dead. Long Live the SVR!

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Notes and Sources

Introduction

What makes a woman volunteer to become a secret agent, knowing that, if caught by the enemy, she risks sexual violence in addition to the injuries, imprisonment and tortures that may be inflicted on male comrades? If she is a mother, she also may be putting her children at horrific risk. Yet some women are courageous enough to do that. Espionage has been described as ‘the second oldest profession’ and the anger of the men they outwitted has often had these courageous women labelled whores. It is an age-old sexist slur, sadly given modern currency by misogynist Islamic fundamentalists, but some were indeed whores. Three-and-a-half millennia before Mata Hari, the history of women agents goes back to the Old Testament Book of Joshua, which records how Rahab, a ‘harlot of Jericho’ – that most ancient of cities – risked her life to hide two Hebrew spies during Joshua’s conquest of Canaan c. 1400 BCE.

If female agents have generally received less acclaim than their male counterparts, this is because spying is widely and wrongly treated in fact and fiction as ‘a boys’ game’. Even if those agents were also ladies of the night and used their feminine wiles and sexual favours to obtain information, or escape capture, is that wrong? If a woman beds several men in the course of her clandestine life, is that somehow reprehensible when a James Bond in fiction or a Sidney Riley in fact treated women as tools of the trade or toys for their pleasure, and are heroes?

This book is not just about women who spied and their motivations for doing so. It also looks at other clandestine work that is better done by women, partly because of their personal qualities and partly because, even today, her male enemies are still less suspicious of a woman apparently going about her daily business than of a man in the same place at the same time. A friend of the author who was a teenage girl during the German occupation of France recounted how, when transporting incriminating material in the basket of her bicycle, she talked her way through several checkpoints by flirting with the sentries checking her papers, to distract them. Polish countess Krystyna Skarbek, alias Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent Christine Granville, outwitted Germans troops hunting her in the Alps during 1944 by dressing as, and pretending to be, a simple Italian peasant girl. She also had the nerve to reveal her true identity to a Gestapo officer when bluffing him into releasing her boss and lover Francis Cammaerts, just hours before he was to be shot during the US–French invasion of southern France in August 1944.

Much has been written about the women agents of SOE. Yet, in a debate in the House of Lords on 6 June 2011, Baroness Crawley of Edgbaston urged the government to make a gesture commemorating all the women sent into France by SOE. Her speech included the following:

Apparently, they had each been told when recruited that there was only a 50 per cent chance of personal survival. Yet, to their eternal credit, off they went. Some were already mothers; some just out of their teens. In France, they often had to travel hundreds of miles by bike and train, protected only by forged papers and, as they went about their frequently exhausting work they were under constant danger of arrest by the Gestapo. Some were even exposed to betrayal by double agents and turncoats. The story of what happened to those women is often unreadable and, in twenty-first century Britain, is perhaps too easily under-remembered.1

One hundred years before the Second World War, during the American Civil War, 17-year-old Belle Boyd (no known relation of the author) and Rose Greenhow flirted with Union officers and reported their plans to Confederate general ‘Stonewall’ Jackson after a fast ride on horseback through the battle lines. Known as la belle rebelle, Boyd was arrested six times before escaping to Britain. In the same conflict, Quaker-educated anti-slavery activist Elizabeth van Lew spied for the Union.

During the Algerian war of independence French communists known as les porteurs de valises literally carried suitcases full of money across the Mediterranean to finance the Armée de Libération Nationale fighting the French armed forces. When several of these couriers were caught, tortured and killed by their compatriots in uniform fighting a dirty war with the ALN, female comrades volunteered to replace them, thinking they were less likely to be detected. They too were tortured and killed. After suffering multiple rapes, their bodies were dropped from helicopters into the sea.

Hiding wounded combatants from those who would kill them, running an underground railway to help Allied soldiers or black slaves to freedom, or caring for children whose parents have been arrested by an occupying army are just a few of the clandestine acts better done by women. Communist Litzi Kohlman married Kim Philby to save her life in strife-torn Vienna, but went on with Austrian-born photographer Edith Taylor-Hart to talent spot British traitors for Stalin. Berlin-born GRU colonel Ursula Kuczynski was ordered by Moscow to divorce her Soviet husband and marry British communist Len Beurton as cover. She later said that the nappies on her washing line and a pram in the garden threw MI5 officers completely off her scent during the period when she was transmitting thousands of messages to Moscow from Soviet agents in the UK, including Tube Alloys atomic bomb project spy Klaus Fuchs, recruited by her brother. Also spying at Tube Alloys was Lithuanian-born Melita Norwood – dubbed ‘the Red Granny’ when blown by renegade KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin in 1989. Croatian–American Frieda Truhar spent the 1930s travelling the world as a Communist International (Comintern) courier, carrying huge sums of Moscow’s cash stitched into her corselette. She risked arrest by the British police in Shanghai hunting communist agents, but her most pressing problem was an American male comrade who thought her body was common property.

This book explores why female agents from all social backgrounds and many different countries volunteered over the centuries for this dangerous life, how effective they were and what training, if any, they were given. Were the odds against them in the field better or worse than for men, given that some were apparently regarded as disposable assets by male spymasters? Some of these regarded them as inherently unreliable because they might fail to kill when necessary or were prone to form emotional attachments in the field, and even change allegiance for a lover.

In fact, the list of achievements of these courageous women is long and their many motivations fascinating: political or religious belief, love, patriotism, revenge, anger and compassion. Their achievements deserve not to be forgotten because, as Mathilde Carré, who betrayed her Resistance comrades to the Gestapo, said at her post-war trial, ‘It is different for the women.’

1

The Perfect Cover for the Perfect Spy

In May 1907 a daughter was born to economist Robert Kuczynski and his artist wife Berta, who moved shortly afterwards to the pleasantly wooded suburb of Schlachtensee, south-west of Berlin, near the Havel lake. Named Ursula Ruth, this girl attended the prestigious Lycée Français and afterwards served a two-year apprenticeship as a bookseller, which was a respectable profession for the daughter of a middle class intellectual Jewish family. Already at the age of 17, her politics were far left, as were those of her parents. Whereas they hid their sympathies, she did not, joining the Allgemeiner Freier Angestelltenbund, or Union of Free Employees, and the Kommunistischer Jugendverband Deutschlands, which was the German Young Communist League. She was also appointed leader of the Propaganda Section of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD), after which time her political activities took up so much time that her ‘day job’ with the major publishing house Ullstein Verlag was lost for lack of application.2

With her father Robert and older brother Jürgen – both already working as agents of Soviet military intelligence Glavnoe Razvedyvatelnoe Upravlenie (GRU) – Ursula moved to New York in 1926, using the cover of her father’s work as an economist. While there, she seems to have worked in a bookshop for some months before returning to Berlin and marrying Rudolf, or Rolf, Hamburger, who was a qualified architect and also a GRU agent. In July 1930 the couple moved to China, where Rudolf had been offered a job with the Municipal Council of Shanghai, a city then enjoying a construction boom. His salary, augmented by the funds supplied by GRU, enabled them to mix with the prosperous foreigners of the international settlements. The city was a hive of espionage with several high-ranking Comintern agents, including Elise and Arthur Ewert, whose paradoxical brief at the time was to muzzle the Chinese communists because Stalin then wanted Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek as his ally.3 Within a few months of the Hamburgers’ arrival, their son, Michael, was born. By that time, Ursula had already been introduced by US journalist and Comintern agent Agnes Smedley to German expat Richard Sorge, a senior agent of GRU, and was using the name of Sonya4 Hamburger, to dissociate herself from her overt political work as Ursula Kuscynski in Germany. For two years – whether or not with Rudolf’s knowledge – she and Sorge had an affair under the cover of his training her in espionage techniques. Smedley, too, played an important part in her life, coaching her in journalism for the worldwide communist press.

In late 1933 Sonya was ordered to Moscow for seven months’ training in tradecraft, microphotography, Morse code, cryptography and the building, operating and repairing of radio transmitters. During this time, her son was sent to live with his paternal grandparents in Czechoslovakia, so that he did not happen to pick up any Russian words and blurt them out afterwards. She was then posted to Mukden – modern Shenyang – in north-east China, which was an important centre of Japanese expansion. Her official job there was working for an American book publisher, but this was just cover for her activities as a channel between GRU in Moscow and the Chinese partisans fighting the Japanese in Manchuria. Shortly after arriving in Mukden, she became pregnant by a top Soviet agent, cover name ‘Ernst’, who may have been US diplomat Noel Field.5 In August 1935 she was ordered to leave China after the arrest in Shanghai of Sorge’s replacement there. Since the prosecution of communist agents was one of the few areas where the Western police forces in the international settlements collaborated with the Chinese police – the latter using torture routinely – Moscow’s fear was that he might disclose details of other agents while undergoing interrogation.

She departed with Rudolf, using his contractual entitlement to home leave, for London, where Sonya’s father was living under the cover of lecturing at the London School of Economics, having taken advantage of the influx of Jewish immigrants after Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933. Also staying with Sonya’s parents was her old nursemaid, Olga Muth, who took charge of Michael and Nina, the daughter of Ernst, when Sonya and Rudolf were assigned to Poland by the GRU. In June 1937 Sonya was recalled to Moscow, where so many of her fellow agents had been liquidated in Stalin’s purges for real or imagined failings, or simply to keep them from talking about their work. In her case, it was to be invested with the Order of the Red Banner and promoted, which makes it clear that she had already accomplished important clandestine tasks.

The purges had killed off the main players in the GRU network in Switzerland, which Sonya was now appointed to rebuild, settling with Muth and her two children in a mountain village near Montreux in September 1938. It was during this period that Rudolf had had enough of their relationship and was posted at his own request back to China, his place in Sonya’s bed being taken by Alexander Foote, a British veteran of the Spanish Civil War, recruited as her clandestine radio operator by Sonya’s sister, Brigitte, living in London. When Foote arrived in Switzerland, to take up his GRU duties, life for him and Sonya was very comfortable thanks to money supplied from Moscow, laundered through the Irving Bank in New York and passed on to them by Swiss lawyer Dr Jean Vincent, who had been working for the Comintern in China.6 Although Sonya was regarded as the head of the new Swiss network, she claimed to have been ordered in December 1939 – this was during the phoney war – by her Russian superior Maria Polyakova to hand her network over to Alexander Rado, head of the Lucy network, also called ‘the Red Orchestra’. Whatever blow this might have dealt to her professional ego was salved by her sister Brigitte, acting as a GRU talent spotter in London, sending out another British survivor of the International Brigades in Spain named Len Beurton,7 who replaced Foote in her bed and affections from his first night in Switzerland.8

In fact, the apparent demotion was part of a convoluted GRU plot to move Sonya into position for even more important work without the knowledge of any of her current GRU and Comintern comrades. Many loyal Party members all over the world, who had believed they were fighting fascism in all its forms, were deeply disillusioned that the Nazi–Soviet Non-Aggression Treaty signed by Molotov and von Ribbentrop in the previous August had allied the Soviet Union with the most extreme fascist government in Europe. Thousands tore up their Party membership cards. It was therefore quite credible when Sonya began complaining that the Treaty had shattered her belief in Stalin and communism, also that she was afraid Hitler would shortly invade Switzerland and liquidate her and her children, together with all the other Jews in the country. As a result, she said, she wanted out of her clandestine life before it was too late.

The truth was that the GRU was playing a very long-term game, in which she was required for a deep cover operation in Britain, which needed her to obtain British nationality by divorcing Rudolf Hamburger and marrying Foote. Unworried by this order from Moscow, Sonya chose instead to marry Beurton and received a British passport as his wife. The fly in the ointment of this neat arrangement was the nursemaid Muth who, being German, would have been an embarrassment in Britain at war. Distraught at the prospect of losing all contact with the two children whom she loved, Muth headed for the British consul in Montreux to denounce Sonya as a Soviet agent.9 What action he took, if any, is unknown, but the news apparently never reached London.

Travel in Europe was already complicated in late 1940 with many people stranded in countries they wanted to leave, but Sonya was more than equal to this. She and her children managed to reach Lisbon and take a ship for Liverpool, where they arrived in mid-February 1941, leaving Len behind in Switzerland to avoid him being called up in Britain. Playing the part of a distressed Jewish refugee, Sonya was invited to stay in a vicarage near Blenheim Palace, to which much of the British counter-espionage organisation MI5 had been evacuated from bomb-damaged London. It was in Blenheim Palace that her first agent was working, so she rented a bungalow in nearby Kidlington and commenced clandestine radio communications with Moscow. This agent may have been Roger Hollis, later director-general of MI5, who had been a freelance reporter in Shanghai at the same time at Agnes Smedley and was often seen there in her company. Since both were journalists, their association may have been entirely innocent but it is a coincidence that he lived in the same village, less than a mile from Sonia and her father, both of whom lived within easy distance of a dead letter drop in the graveyard of St Sepulchre’s cemetery. Hollis was also in charge of an MI5 section charged with watching Soviet and other spies in Britain. When Sonya’s deeply encrypted messages were picked up by the Radio Security Service operating under MI5 section MI8c, it was up to Hollis to decide whether or not to use direction-finding vans to track down the transmitter. He decided not to.10

With Sonya’s brother, father and sister all working for GRU, Britain thus had accepted as refugees four GRU agents from one family working for the USSR, an ally of the Axis enemy. She bought a bicycle for apparently innocent rides through the countryside in this time of severe petrol rationing; her motive was not fitness but visiting this and other dead drops serviced by her agent in Blenheim Palace to collect his or her material for transmission to Moscow. Len Beurton was finally ordered by the GRU to join her in Britain in July 1942 and was drafted, some months later, into the RAF, where his time was not wasted. He obtained and gave to Sonya copies of technical drawings of the latest British aircraft and, in various postings, contacted men who had been communists before the war, and now had specialist military or political knowledge, whom he enlisted as additional sources. Technical drawings, whether from Len or Fuchs, presented a problem, which was solved by Sonya passing them to a man in London, whom she knew only as ‘Sergei’ – presumably via a dead letter drop.11 This was Simon D. Kremer, a member of the military attaché’s staff at the Soviet Embassy in London, who was also a GRU officer.

The far-sightedness of the GRU’s move in bringing Sonya to Britain was clear when Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa on 22 June 1941, with Stalin unwilling for several days to believe this was more than a local incursion despite clear warnings from Churchill and Sorge, working under cover in the German embassy in Tokyo until he was arrested and garroted in a Japanese prison. It was Sonya’s transmitter that sent the top level news to Moscow that the British War Cabinet did not intend to supply materiel to the USSR because it considered the Soviet defences would collapse in a matter of weeks, such was the initially rapid progress of the Axis onslaught. Her source for this intelligence was most probably her father, who was frequently consulted as an economist by Marxist politician and former ambassador to Moscow, Stafford Cripps, a member of the War Cabinet.

In late 1941 Sonya’s brother, Jürgen, was approached by the socially inadequate but intellectually brilliant theoretical physicist Klaus Fuchs, another of the 400-odd KPD members living as refugees in Britain.12 Employed on British nuclear research, which was still in its early stages, Fuchs offered to pass top secret material to Jürgen, for him to send on to Moscow. Jürgen handed Fuchs over to Kremer, who was known to Fuchs only as ‘Alexander’. They had four meetings over a period of six months in a safe house near Hyde Park, with Kremer trying and failing to instil the rudiments of tradecraft, and was understandably alarmed when Fuchs called openly at the embassy to make sure ‘Alexander’ was genuine! Starting in autumn 1942, Fuchs was instructed to pass material to Sonya or leave it in a dead letter drop near her home in Oxfordshire when visiting his refugee parents, who had moved there from London – ostensibly as evacuees but perhaps as accessories. To begin with, Fuchs handed over only his own research, feeling that he should not ‘betray’ his colleagues by stealing theirs, but this qualm of conscience was eventually overcome by Marxist ‘logic’, leaving him free to pass over everything to which he had access.13

In late summer 1943 a son was born to Sonya and Len Beurton, whom they named Peter. The ‘happy event’ did not long interrupt her clandestine work, transmitting to Moscow material from several agents including Fuchs and Lithuanian-born Melita Norwood, working as a secretary at Tube Alloys – a lowly position that nevertheless enabled her to read top secret material passing through her office. Working with Jürgen in London was another top flight GRU agent, who had been allowed to enter Britain as a German refugee from Nazi Germany’s anti-Semitic laws. This was Spanish Civil War veteran Erich Henschke, using the cover name Karl Kastro, whose penetration of the fledgling American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), created in June 1942, ensured that many of the émigré Germans parachuted as agents behind the battle lines into the Third Reich during the war – in an OSS operation code-named Faust in reference to Goethe’s character who was avid for all knowledge – were more loyal to Moscow than to Washington. Handling material from all these sources, Sonya was the most important GRU asset in Britain, beautifully concealed from suspicion by her role as a housewife and mother. With two young children playing beside Peter’s pram in the front garden and a row of nappies on the washing line, who could suspect her? This was a cover identity no man could have equalled.

It was through Fuchs that she was able to pass on to Moscow in 1943 news of the UK–USA agreement to pool nuclear research. When he was transferred to work on the Manhattan Project in the USA, she handed Fuchs over to USSR consul-general Anatoli Yatsov, also using the name Anatoli Yakovlev, who was the senior GRU officer in the United States.14 Although Fuchs’ traffic no longer went through Sonya, her transmissions to Moscow of material from other sources continued; in November 1944 ‘Sergei’ conveyed the appreciation of GRU Moscow Centre and handed her a more efficient and smaller transmitter, after which she dismantled the one she had built, keeping the parts as standby in case of need.15 After the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, Fuchs returned to Britain to occupy an important post in Harwell nuclear research station, from where he continued to feed highly secret information to Moscow via Sonya. At the end of the war, Sonya, Len and the children moved to Great Rollright in Oxfordshire, which became the family home, so to speak, with both Sonya’s parents eventually buried in the local churchyard. It was here in 1947 that she was twice visited by MI5 officers and admitted her communist sympathies, while denying that she had ever been a spy. Also living in the house at Great Rollright was an English couple named Greathead. Madeline, the wife, afterwards recalled that Sonya asked her to help with the housework while she spent hours each day at her typewriter, carefully burning every page at the end of the day. A photograph Madeline took of Sonya shows a laughing young mum apparently without a care in the world except for mumps and whooping cough. Madeline was also asked to look after Sonya’s children during their mother’s frequent visits to London, but she and her husband were not allowed to use the cellar, where Sonya’s transmitter was concealed.

The Western world was staggered by the explosion on 29 August 1949 at the Semipalatinsk testing ground in Central Asia of the USSR’s first nuclear bomb, which was not surprisingly a near copy of the Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki. This was several years earlier than the USSR would have been able to produce a nuclear device without the material from Fuchs and other Soviet spies working on the Manhattan Project. To prevent further leaks, the FBI in America and MI5 in Britain made it a top priority to identify by whom and how the top secret documentation and samples of plutonium had been passed to Moscow. Fuchs’ eventual undoing came through the Venona programme of decryption of encoded spy traffic from the USA to Moscow, conducted by the male and female code-breakers of the US Army’s Signals Intelligence Service at Arlington Hall in Virginia. This led to his arrest in January 1950, shortly after which Sonya decamped with the three children to Soviet-controlled eastern Germany, newly constituted as the German Democratic Republic, telling them that they were going on holiday. It was a great disappointment for the children when they discovered they were never going home to Great Rollright again and were stuck in a grim, war-damaged country whose language they could not speak. Len had recently broken a leg and followed as soon as he was fit to travel. It is thought by some people in the Intelligence community that Sonya may have been warned by none other than Roger Hollis, then a rising star inside MI5, of the risk of her being implicated in the Fuchs investigation.

Put on trial in January 1950, Fuchs confessed to his espionage activities in Britain and the USA. In November, having given her plenty of time to escape, he named Sonya as his GRU contact. Her cover now blown internationally, Sonya resigned from the GRU or was ‘let go’ but left at liberty, unlike so many of her fellow spies, who were ‘pensioned off ’ in a Gulag camp or shot so that they could never talk about what they had done. Immersing herself in the life of a civil servant in the rigidly controlled society of the GDR,16 she was at one point fired from the State Information Office, so it may well be that her new life was deeply unsatisfying to this woman who had spent so many years controlling important agents and outwitting the best counter-espionage brains of the free world – which could have made her a very difficult subordinate. Len, meanwhile, was working for the GDR news agency ADN. In 1956, after some intermittent journalism, Sonya published the first of her several books, which was the last time she used the name Sonya Beurton. More volumes followed from various GDR state publishing houses, some for children, but all in her new name, Ruth Werner. In 1977 her book Sonjas Rapport was a highly sanitised account of her espionage activities without mention of any colleagues who were still alive.17

This extraordinary woman, who had been twice awarded the Order of the Red Banner18 and numerous other Soviet and GDR honours, denied that she had been a spy, let alone a major spymaster, claiming, ‘Ich arbeitete bloss als Kurier.’ I was only a courier. She remained an implacable apologist for Stalin and his discredited brand of Soviet communism, even after Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciations of the former dictator at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR on 25 February 1956, listing among other crimes Stalin’s murder of ninety-eight of the 139 members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1937–38. Nor was she moved by the fate of Rudolf Hamburger and Sandór Rado, among other loyal comrades with whom she had worked who were sent to the Gulag after years of devoted service to the cause of Soviet communism. She simply said, ‘They must have made errors.’ When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 and 99 per cent of East Germans rejoiced in their new liberties, Ruth Werner pleaded publicly for the continuation of what she called ‘socialism with a human face’ – which is not how many people would have described the harshly repressive regime of the GDR.

Her source, Klaus Fuchs, was released from prison after serving nine years of his fourteen-year sentence, and also moved to the GDR. Sonya’s other source inside Tube Alloys, Melita Norwood19 was publicly outed in 1999, although MI5 had become aware of her espionage activities even before they were revealed by KGB archivist Vasily Mitrokhin in 1992. After a long struggle with Parkinson’s disease, Len Beurton died in Berlin in October 1997, followed nine months later by his wife. They were survived by three children, five grandchildren and three of the Kuczynski sisters.

2

Handmaidens of the Red God

The Cold War is often said to have started in 1945 as a consequence of the Second World War. This is wrong. It began a quarter-century earlier. The Communist International, its title generally abbreviated to ‘Comintern’, was founded in Moscow in March 1919 as a tool to subvert foreign, i.e. non-Soviet, trade unions, disseminate Soviet propaganda, finance civil and industrial unrest worldwide and exploit all the weaknesses of the so-called ‘bourgeois democracies’, to achieve a worldwide quasi-communist revolution controlled by Moscow. With all the double-talk and glib promises pared away, it was a subtle way of expanding the Russian Empire – which already reached from the Baltic to the Pacific and from the White Sea to the Black Sea – to place the whole world under Soviet hegemony.

The thousands of Comintern agents despatched into the West on these missions included many nationals of the target countries, especially women, who were in those days far less subject than their male comrades to surveillance by counter-espionage organisations such as MI5 in Britain. No one knows exactly how many non-Soviet women were devoted servants of the Comintern. What follows illustrates some of the many different ways in which they served.

Edith Suschitzky, more famous as a photographer under her married name of Tudor-Hart, was born on 28 August 1908 in Vienna, then the twin capital with Budapest of the Austro–Hungarian Empire. Her father owned a bookshop, which was a natural meeting place for academics and intellectuals, and the family had sufficient funds to send Edith to the Bauhaus in Dessau and for her to train as a Montessori kindergarten teacher. Like many other Central European Jews, the Suschitsky family was pro-communist, and Edith used her camera technique to photograph social injustice, mixing in a milieu that inevitably included Bolsheviks and other revolutionary socialists.

The capital was a fertile ground for her kind of photography, since Austria had lost both the war and its empire. Refugees, war wounded men and blind and deaf people begged openly on the streets or busked for coins if they could play an instrument. Her photographs showing adults and children in rags, some with no shoes and no access to clean water or heating in winter, remain a harrowing social document. According to historian Nigel West, in addition to being a known member of the banned Austrian Communist Party, she had been commissioned on occasion by TASS, the Soviet news agency, and undertook clandestine missions to Paris and London for the Comintern in 1929.

Aged 18, she met a British communist named Alex Tudor-Hart, who was studying orthopaedic surgery in Vienna. He had been married before and Edith was a liberated young woman. After a seven-year relationship that included the birth of an autistic son in 1927, the couple married at the British consulate in 1933 when Edith was released from jail after arrest as a highly visible left-wing agitator. The wedding enabled Alex to bring her to Britain, where she had won respect on a previous visit as an inspiring teacher of young children. With the coming to power of Hitler’s NSDAP in neighbouring Germany and growing police violence against left-wing demonstrations in Austria too, it was a good time for a woman who advocated birth control and sex education for children – and was also Jewish – to be leaving Vienna.

Edith was already working for the Comintern, having been recruited by agent runner Arnold Deutsch.20 After three years as a general practitioner in the depressed mining areas of the Rhondda Valley, Alex went to Spain, working as a surgeon for the International Brigades fighting Franco’s fascist troops in the civil war, while Edith continued her photographic career in Britain, exposing the plight of working class families in industrial areas and receiving commissions from several respected British magazines, of which the best known was the iconic Picture Post. Although 35mm cameras were cutting edge for photo-reportage, thanks mainly to the cinema industry producing vast quantities of that gauge of film very cheaply, Edith preferred using a bulkier 2¼ in square Rolleiflex both because the definition was better and because it was held at waist level, leaving her face visible to her subjects, which she thought important.

Edith’s work for the Comintern at this stage is hard to evaluate. Vivacious and extravert, she did not keep the low profile of a trained agent, but played an active part in politically committed exhibitions, making no secret of where her sympathies lay. She did not even take the elementary precaution of using a code name, but was known to comrades in the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) under her own name. As another example of her imprudence, in March 1938, a Leica camera belonging to her was found during a police raid on the home of a CPGB member called Percy Glading, subsequently convicted of organising the Woolwich Arsenal spy ring for Moscow. Presumably, she had lent it to him for photographing documents illicitly borrowed from the arsenal but, when questioned by Special Branch detectives, Edith denied knowing how it came to be there. She was not charged with any offence, despite being under intermittent watch by MI5 ever since she came to Britain with her husband.

However, she did show great flair as a talent spotter for the Comintern, concentrating especially on privileged students at Oxford and Cambridge. The most famous of her finds was Kim Philby, who had married Litzi Friedman – an Austrian Jewess very active in the left struggle there – in Vienna so that she could emigrate to safety in Britain as his wife. In 1934 the two women recommended Philby to Edith’s own handler, Arnold Deutsch, then living in Britain, ostensibly as a post-graduate student of psychology.21 At a meeting in Regents Park on 1 July 1934 the two men met. Deutsch approved the choice of Philby, who had had – to put it mildly – a complicated upbringing, with his anti-British father living in Saudi Arabia with a slave-wife, given to him as a present by Ibn Saud, and his British wife in Britain kept perennially short of money. Their son’s natural talent for deceit impressed Deutsch, who was also interested in Philby’s ambitions for a career in diplomacy, journalism or the civil service. Deutsch’s training in tradecraft of this recruit was to prove so watertight that Philby betrayed Britain for more than three decades, together with the other Cambridge spies. Among other future spies Edith spotted at Oxford were Arthur Wynn and Anthony Blunt.

Under the Nazi–Soviet Friendship Pact, the USSR was an ally of Hitler for the first twenty months of the war, so the Soviet Embassy in London had to be closed down in February 1940, after which Edith acted as a go-between for the Comintern and its British agents. Later in the war, she had to give up her studio in Brixton and with it her career as a freelance photographer. After 1945 she found life increasingly difficult, with a handicapped son to bring up and a slow but steady decline in commercial interest for her kind of politically committed photography. The result was a nervous breakdown after the boy was taken into care. At one point she was employed as a housekeeper and did very little professional photography, although her pictures of children were praised, even by the Ministry of Education. In 1951, as the Cold War intensified, she took the difficult step of destroying most of her photos and negatives, from fear they would be used as evidence against her if she were prosecuted. Attempting to get back on her own feet, she opened a small antiques shop in Brighton and died in a hospice there on 12 May 1973 of stomach cancer.22

It is not easy in the second decade of the twenty-first century to understand the motivation of the thousands of women and men who volunteered through seven decades to spy on their own countries for the USSR, carry the Comintern’s orders to foreign parties, clandestinely transport vast sums of money around the world to finance the worldwide revolution planned by Lenin and, on occasion, conduct industrial or marine sabotage. A critical role was played by the couriers who could pass as citizens of Western democracies, travelling on their own or false passports. They were thus mostly not Soviet citizens and, because women were less likely to be suspected in those days, many were female. These mysterious agents of the Comintern took very real risks of arrest, and worse, in many countries. They came from rich homes and poor ones, but all thought that they were ‘making a better world’ through the imposition of Marxism–Leninism after the destruction of the status quo.

Frieda Truhar was born in 1911 to Croatian immigrants who had settled in a grim Pennsylvanian steel town after migrating from the Balkans. She grew up witnessing her father and other men doing dangerous underpaid work in steel mills and mines, where hired thugs broke up strikes and armed police put men and women in jail for demanding improved working conditions or fair wages. Her first political steps were taken at the time of the October Revolution, when she was 7 years old, distributing leaflets during the ‘Hands Off Russia’ campaign and collecting coins for ‘the starving children in Russia’. In 1919 the massive strike of United Steelworkers of America, the union to which her father belonged, closed down every steel plant in western Pennsylvania. Reprisal came swiftly in what were known as ‘the Palmer raids’. On 2 January 1920 US Attorney-General Mitchell Palmer had 6,000 union activists jailed. After twenty-two union organisers were killed in the raids, all those not arrested went into hiding, many staying in the Truhar family home, used as a safe house for comrades on the run.

At the time of the Wall Street crash of 1929, Frieda was reading economics at the University of Pittsburgh, where she earned the reputation of an outspoken socialist and feminist. Collecting money for the families of striking textile workers in North Carolina imprisoned on charges of murdering strike-breaking thugs sworn in as deputy sheriffs, she was arrested and spent her first night in jail, singing The Red Flag to keep her spirits up. Her father being unemployed like millions of other men, she had to leave college and take a poorly paid job in an engineering factory, where she met an older Scottish activist named Pat Devine, who swiftly banished her feminist ideals. As she later realised, he wanted an impressionable communist virgin who would worship him and have no previous experience with which to compare his performance in bed, while she was in love with the political hero, not the man. Despite all the talk of sexual equality between socialist comrades, ‘reality turned out to be making his meals, providing clean shirts and being available in bed when he wanted’.23

The far from feminist marriage was interrupted by Devine’s arrest for illegal entry into the United States. While he was in jail, Frieda manned picket lines and organised welfare for families of the unemployed, but felt unable to cut loose from her husband, whose imprisonment made him a martyr for the cause. On release, he was deported back to his native Britain. The marriage had been a deep disappointment for 20-year-old Frieda, its lowest point coming when she had an abortion because Pat refused to let her bear his child. When she announced that she did not intend to follow him to Britain, Frieda’s mother, who had always preached feminism, argued that a communist woman’s place was with her husband – in proof of which she herself was going to accompany her husband to Russia, where he had signed on ‘to build socialism’ as a bricklayer in a new steel town on the Asiatic slopes of the Urals.

Bowing to this bourgeois–communist morality, Frieda skipped bail to rejoin Devine in Britain early in 1932. It was a lonely period. Apart from brief conjugal visits, he lived his own life as a travelling activist of the CPGB. He was in jail once again when Willie Gallagher, a founder member of the party, introduced her to its secretary-general Harry Pollitt, who gave Frieda work as a secretary in the CPGB’s King Street headquarters. Before she had adjusted to life in Britain she was ordered by Devine to join him in Moscow, where he had been promoted to work at Comintern headquarters. She wrote later:

My emotions as I disembarked in Leningrad might be compared with those of pilgrims to Mecca or Rome. The briefest glimpse of the city as I drove to the station, drab streets, unpainted buildings, gold-domed churches glistening in the late afternoon sun, a sparkling river spanned by a beautiful bridge. Then the overnight train to Moscow.24

Lodged in the shabby Hotel Lux, overcrowded with other ardent workers for worldwide revolution from many countries, who included her cousin Sophie, Frieda worked in the Comintern typing pool near the Kremlin. The foreign comrades had little contact with ordinary Russians, but she could not help seeing malnourished men and women begging in the streets and the starving besprizorny – homeless orphans with distended bellies and desperate eyes, dressed in rags, pleading for food. Other Soviet citizens spent hours each day queueing outside empty stores, on the off-chance that anything might be delivered. In contrast, the Comintern workers were allowed to use the valyuta stores of the nomenklatura25 to buy luxuries never seen in ordinary shops. Even there, things such as coffee, chocolate and feminine hygiene articles were unobtainable, and were brought in by comrades returning from missions in the West, to be shared around. Occasionally, when a comrade returned from a dangerous illegal assignment abroad, there was a party with plenty to drink, but never much to eat.26

The living conditions were so appalling that Frieda joined other women in a naked protest against the inadequate and filthy showers. The Comintern staff took their meals in the Lux canteen, which was run on the basis of Orwell’s Animal Farm: all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others. Sophie and Pat were graded Class 1 employees of the Comintern and had chicken plus extra food parcels while Frieda, a Class II typist, received just one meatball for her supper. Defying their unthinking acceptance of this privilege, she divided food equally and even shared hers with other girls in the typing pool.

Devine had no place in his selfish lifestyle for paternity. When she became pregnant again because he refused to use condoms, he was furious, accusing her of being responsible for the problem. Abortions in Russia were frequent because few Russian men would use contraceptives. Devine procured a rail ticket for Frieda to visit her parents, more than 1,000 miles to the east of Moscow, so that she could have the abortion where her mother could look after her. Instead, Frieda decided to have the child, which was still-born. Back in Moscow, she received no sympathy from Devine, but her post-natal depression lifted when she was invited to the Bolshoi Theatre and met, in the former royal box that was permanently reserved for the Comintern, its boss Georgi Dimitrov:

All that evening I looked more at Dimitrov than at the performance of Othello. It was the most memorable moment of my young life and I was the envy of all my friends in the Lux.27

That meeting at the Bolshoi began Frieda’s lonely and dangerous life as an illegal courier, using the British passport that marriage to Devine had given her. She knew it all: international train journeys carrying secret documents and considerable sums of money in her clothes; secret compartments in her luggage; furtive meetings in Paris, Amsterdam, Prague, Zurich, Basel and Hitler’s swastika-bedecked Berlin with strangers who exchanged passwords and vanished into the shadows. Occasionally, she took a plane – a rare event in those days – to avoid passing through hostile countries carrying something of which the discovery would have been fatal for her. Then back to the sordid Hotel Lux, to find that Pat was sleeping in her absence with other women there, all captivated by his political record.

With all the foreigners cooped up in the Lux that was common enough. But, although it was against all the rules, Frieda had fallen in love for the first time in her life with her contact in Vienna and was impatient to be sent back there. However, her successful European missions earned her an unwanted promotion. She was 23 years old in the autumn of 1934 when ordered to take funds to China, a country torn apart by the civil war between Chiang Kai-Shek’s Kuomintang Army and Mao Tse-Tung’s Red Army, fighting its way across several thousand miles of the war-torn land in the Long March.

At this point, Stalin was still thinking he would be able to control a China emerging from the chaos of the warlords and the civil war. With the Kuomintang preventing commercial bank transfers to their enemies, Frieda’s mission was to smuggle in American banknotes worth US $100,000 – equivalent to more than $1.5 million today – to purchase arms for the Reds. She travelled to London, to obtain a new passport without all the giveaway European visas and was told by an older woman comrade to wear a full body corselette, in which to conceal the money. As the weather got hotter onboard ship in the Indian Ocean, it was an uncomfortable assignment.

In Shanghai, the squalid Chinese quarters contrasted with the luxury of the international settlement, where Chinese were admitted only as servants, and seemed to confirm her political beliefs. After handing over the cash, she was relieved at last to take off the sweaty corselette, but dismayed when ordered to remain in Shanghai and give the appearance of respectability to a safe apartment where an illegal transmitter was hidden. At the time she had no idea that the two Chinese radio operators of the Shanghai cell’s link with Comintern Centre had recently been arrested and tortured into giving away the whereabouts of their transmitter. Her most pressing problem was not the British security police searching for her, but the American replacement radio operator, who expected Frieda to service his sexual needs on demand. After several months of jamming a chair under her bedroom door handle each night, to keep him out of her room, Frieda had to leave Shanghai hurriedly when her name was placed on a British arrest list. Since the savagely repressed 1927 communist uprising in Shanghai, the Chinese, French and international settlement police forces collaborated on one thing only: hunting down communist agents. Of Frieda’s Comintern comrades, at least one had been assassinated by the Chinese police in collusion with British Military Intelligence.

Smuggled aboard a Soviet cargo ship with a suitcase in which were concealed highly incriminating documents, she endured a typhoon in which other ships were sunk nearby and entered Vladivostok harbour behind an ice-breaker. After a week on the Trans-Siberian railway, she was back in Moscow, handing over the documents and being debriefed. Expecting high praise for the risks she had run in China and the initiative she had shown, she was allocated a dirty bedroom at the Lux and awoke covered in lice, with the house doctor mocking her fears of typhus, from which one of her friends had died in Russia. Commuting again to European capitals, carrying money and compromising documents, Frieda returned to Vienna, made more dangerous since the 1934 Austrian Nazis’ attempted coup d’état, to find that her lover had been arrested and was probably dead.

Frieda’s faith in the cause was still intact, but her mother’s socialist dreams had melted like snow on the water in the remote Urals. Having prudently kept her American passport, she left the USSR after advising her daughter to do the same by applying to rejoin Pat, who had been sent to stoke the fires of revolution in Eamonn de Valera’s Ireland, now independent of Britain. It was as well that she did, for very soon Comintern agents with Frieda’s tradecraft and knowledge were not allowed to leave the USSR, but were shot or sent to the Gulag to keep their mouths shut. Frieda’s disillusioned father, having Russian citizenship, was refused an exit visa, but Cousin Sophie’s close relationship with Dimitrov procured an impressive-looking document covered in Comintern seals that frightened the frontier guards into letting him cross the border.

Joining Devine in Ireland, she found that her new enemies were not the local fascists, but priests who inveighed against communism as the Antichrist and granted absolution to their communicants wanting to throw Devine into the River Liffey. Retreating prudently from Ireland with him, Frieda settled down to life as wife and mother in Britain, doing occasional work for the CPGB including standing outside London’s Victoria station surreptitiously handing rail tickets for Paris to British volunteers illegally heading for the Spanish Civil War. Later, as Europe headed into the Second World War, the CPGB toed an anti-Nazi line until ordered by the Comintern secretariat in Moscow to reverse its policy in accordance with the Nazi–Soviet Non-Aggression Pact. In London, Pollitt and others were incredulous that the CPGB was being ordered to support a fascist enemy, whose actions in Spain he had personally witnessed. Frieda was in the audience at a noisy meeting when party cards were torn up, with Pollitt and others made to eat crow. Later, she wrote:

Depressed by it all, I sat still, my son quiet in my arms. I felt unable to grasp this, let alone get up and challenge it. Again, that phrase, which had been dinned into us, surfaced: ‘Moscow knows best.’28

Divorced from Devine, Frieda married fellow-CPGB member Charlie Brewster and lived with him and her two children by Pat. Becoming less active in politics, but never abandoning her communist beliefs, she trained as a teacher and wrote her memoirs, entitled A Long Journey, in 1988. They were not published in her lifetime. By comparison with other internationally active Comintern agents, Frieda Truhar was extremely fortunate not to end her life labouring in the sub-zero Gulag or lying in a grave with a single 9mm bullet in the back of her skull.

One Comintern female agent who came from a different, middle class background was Margarete Thüring, whose father was a prosperous brewer in Potsdam, near Berlin. In the turmoil of post-First World War Germany, both of his daughters espoused socialism because it promised a better future than German women’s traditional lot, summed up as: Kuche, Kirche und Kinder – kitchen, church and children. Margarete’s first marriage to Rafael Buber, a member of Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD) ended in divorce, after which her ex-husband took their two daughters to live with him in Palestine, then under the British mandate. Seeking a purpose in life, she married Heinz Neumann, an MP representing the KPD, when she was 25 and he a year younger. From then on, she called herself Buber-Neumann. He edited the KPD newspaper Die rote Fahne (Red Banner), sat on the KPD Politburo and was a KPD delegate to the Comintern for the rare plenary meetings that Stalin allowed between long periods when the pretence of consultation was ignored and it was overtly controlled from Moscow in the clandestine war against the democracies.

Margarete first visited Moscow with Neumann in 1931. Like Frieda Truhar, she saw it as the Promised Land until faced with a crowd of besprizorny begging for crusts outside a bakery. Although shocked to the core by this evidence that Soviet communism was a sham, she later wrote, ‘The faithful Communist is unbelievably good at excusing negative aspects of Communism as temporary problems on the way to an all-justifying end.’29

In 1932 the Comintern ordered the KPD leadership to support the Nazis in overthrowing the Social-Democratic government of Prussia. With her husband, Margarete refused because this was bound to assist the rise to power of Hitler’s openly anti-communist party. For this disobedience, Neumann was expelled from the KPD Politburo and deliberately assigned dangerous Comintern missions in Spain and Switzerland, while Margarete also undertook courier missions that occasionally allowed the couple to meet. When both eventually returned to Moscow, most of their old friends in the bug-ridden Hotel Lux avoided them in a climate of terror quite unlike the euphoria of 1931–32. Georgi Dimitrov, still general secretary of the Comintern, employed multilingual Heinz Neumann as a translator. Margarete and he were then sent to Brazil on Comintern business, but retribution for Neumann’s disobedience followed when he was arrested on his return to Moscow. On 27 April 1937 he was tried in an NKVD court on a trumped up charge and shot the same day as just another statistic among the hundreds of thousands killed in Stalin’s purges.

Margarete was not told that he was dead. Trying to find in which prison he was being kept, she took a food parcel every day to one jail after another, knowing that the guards would accept it only if the addressee was there. In July 1938 she too was arrested. From Moscow’s grim Butirki prison she was transferred to a hard labour Gulag camp in Kazakhstan, where she would eventually have died from the work, the climate and malnutrition. From that fate she was ‘saved’ by the signing of the Nazi–Soviet Non-Aggression Treaty on 23 August 1939. One of its hidden clauses was Stalin’s undertaking to deliver to Hitler any German communists who were in the USSR. Margarete was transported uncomfortably by rail to the women’s concentration camp at Ravensbrück, known to French prisoners as L’Enfer des Femmes