8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

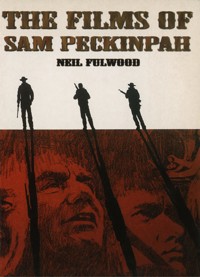

A detailed look at the work of one of America's great film directors. Sam Peckinpah helped to redefine the Western, clearing the board of genre cliches in order to present an intelligent examination of the motivation behind, and effects of, violence. The accusations against Peckinpah for making violent films, both Westerns and non-Westerns, for the sake of it as well as misogyny have become cliches themselves. Like their creator, the men who walk or ride through Peckinpah's films are deep, complex and often flawed. Technical accomplishment and the ability to draw out great preformances from his actors are only part of what sets Peckinpah's Films apart. It is their depth and intensity that make them unique. This book takes an in-depth look at the man, his early work for television, and all his films. It covers the critical reception of his films, Peckinpah's approach to film direction, his on-set behaviour, and studio interference during editing. An Appraisal of the iconography of his films plus an analysis of recurring themes and pre-occupations show that his best work was the most personal.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 412

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

THE FILMS OF SAM PECKINPAH

NEIL FULWOOD

CONTENTS

Filmography

Introduction: Bloody Sam

Chapter One: Redefining the Western

Chapter Two: The Wild Bunch

Chapter Three: Relocating the Western

Chapter Four: Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid

Chapter Five: Cross of Iron

Chapter Six: The Later Films

Chapter Seven: ‘Don’t Put Me Down Too Deep’

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

FILMOGRAPHY

TELEVISION

• The Rifleman series (1958–59). Story consultant on the first series. The episodes listed are those he wrote, co-wrote or directed: ‘The Marshall’,‘ The Home Ranch’, ‘The Boarding House’, ‘The Money Gun’, ‘The Babysitter’.

• The Westerner series (1960). Producer. ‘Jeff’, School Day’, ‘Brown’, ‘Mrs Kennedy’, ‘Dos Pinos’, ‘The Courting of Libby’, ‘The Treasure’, ‘The Old Man’, ‘Ghost of a Chance’, ‘The Line Camp’, ‘Going Home’, ‘Hand on the Gun’, ‘The Painting’.

• Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theater (1959). Director. ‘Trouble at Treces Cruces’ (the pilot episode for The Westerner), ‘Miss Jenny’, ‘Lonesome Road’.

• The Dick Powell Theater (1962). Director. ‘Pericles on 31st Street’, ‘The Losers’.

• ABC Stage 67 (1966). Director. ‘Noon Wine’.

• Bob Hope’s Chrysler Theater (1966). Director. ‘That Lady is My Wife’.

FILM

• The Deadly Companions (1961).

• Ride the High Country, a.k.a. Guns in the Afternoon (1962).

• Major Dundee (1965).

• The Wild Bunch (1969).

• The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970).

• Straw Dogs, a.k.a. Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971).

• Junior Bonner (1971).

• The Getaway (1972).

• Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973).

• Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974).

• The Killer Elite (1915).

• Cross of Iron (1977).

• Convoy (1978).

• The Osterman Weekend (1983).

MUSIC VIDEO

• Julian Lennon, ‘Valotte’, ‘Too Late for Goodbyes’ (both 1984).

INTRODUCTION

‘BLOODY SAM’

It’s an unfair epithet, conjured up by critics who mistakenly thought he was no more than a director with a flair for violence. He was considerably more complex than that. Moralistic but not judgmental, tough but vulnerable, sensitive but stubborn. His sense of artistic integrity flew in the face of commercialism. Pressured to reduce the depth and thematic density of his work by studio executives who answered to the dollar, he stuck to his guns. As a result, he was removed from projects, locked out of post-production, his preferred cuts butchered. Almost every film he made was subject to interference. But damned if he didn’t fight for his artistic vision.

Bloody Sam? Bloody-minded Sam, more like.

It’s said that life imitates art. His life and art merged from the start. Whatever line might have been drawn between events behind the camera and the vision he forged in front of it, by the end that line had been worn away by booze and cocaine and a life spent living it like he told it.

Sam Peckinpah made films about men. Men who ride together. And he made them in collaboration with men whose loyalty to him was unchallenged. Actors Warren Oates, L Q Jones, Strother Martin, John Davis Chandler, R G Armstrong, Dub Taylor, Ben Johnson and Slim Pickens, cinematographers Lucien Ballard and John Coquillon, composer Jerry Fielding, editors Louis Lombardo, Robert L Wolfe and Roger Spottiswoode. They were his posse and he the last outlaw, a renegade, a desperado, outliving his time even as he cut a swathe through Hollywood, redefining the way that films would be made.

Maverick that he was, star names would be drawn back to him: James Coburn, David Warner and Kris Kristofferson each notch up three appearances in Peckinpah films, Steve McQueen and Ernest Borgnine two apiece. Even actors who only worked with him the once – William Holden, Robert Ryan, Dustin Hoffman, Al Lettieri, Stella Stevens, Susan George – give tour de force performances that it can be argued remain unmatched by anything else in their respective filmographies.

Part of Peckinpah’s genius was that he could tap into other people’s talent. Take Lucien Ballard. Outside of Sam’s oeuvre, he lensed somewhere in the region of one hundred films, including The Parent Trap, Hour of the Gun, the Elvis Presley vehicle Roustabout, and Breakheart Pass. Undistinguished, all. The best that can be said is that they are nice looking. But on Ride the High Country, The Wild Bunch and The Ballad of Cable Hogue, his technical ability and eye for composition, allayed with Peckinpah’s artistic vision and poet’s soul, transcended nice visuals and took cinematography into the realms of art. Coquillon, too: Michael Reeves’s Witchfinder General(1) was perhaps the only non-Peckinpah project he worked on that demonstrated the clarity of vision of Straw Dogs, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Cross of Iron.

Cinematographer Lucien Ballard, pictured here with Ernest Borgnine on Ride the High Country – they would work together again on The Wild Bunch.

Technical accomplishment and verisimilitude of acting are only part of what sets Peckinpah’s films apart. It is their depth and intensity that make them unique. And if what Peckinpah put on screen is breath-taking, the off-camera excesses that made it possible are just as remarkable. The crazed journey into Mexico undertaken by the ramshackle cavalry outfit in Major Dundee approximates that made by cast and crew. The horror stories that surrounded the production – arduous location shooting, haemorrhaging budget, demonically driven director – precede accounts of the equally lunatic leadership on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo by more than a decade.

Giving direction to Oates, Jones, Chandler, James Drury and John Anderson, who play the Hammond brothers, the antagonists of Ride the High Country, he ordered them to stay apart from the rest of the cast and crew, and to drink and brawl together in order to find the characters’ internal dynamic. A decade later, he applied the same technique on Straw Dogs, encouraging fights and bouts of wrestling. During shooting, T P McKenna suffered a broken arm, and production was shut down for five days when Peckinpah was hospitalised with pneumonia following a marathon drinking session with Ken Hutchinson which ended with them out at Land’s End in the early hours of the morning, in the middle of a storm, singing drunkenly.

Or how about his relationship with Warren Oates? Given an ultimatum by his then wife not to accept a role in The Wild Bunch because of the ill-health he’d suffered during his previous collaboration with Peckinpah, Major Dundee, Oates made the choice between his marriage and his mentor without hesitation. He went to Mexico with Sam, made one of the greatest movies of all time, and got divorced.

Peckinpah’s life away from film-making (such as it was – his need to express himself creatively on the largest possible canvas, the big screen, was overwhelming and all-encompassing; not just a need, but a raison d’être) was often troubled and destructive. It is no coincidence that when his heroes are not indulging in what is today referred to, rather wimpily, as ‘male bonding’, they are contemplating a lonelier perspective: the mistakes they have made, the chances they have passed up, the failure of love. In Noon Wine, an adaptation of a story by Katherine Anne Porter which he directed for television while exiled by the studios in the aftermath of Major Dundee, the breakdown of a marriage, brought about by a single unpremeditated moment of violence, is charted with chilling perception. The film is heartbreaking in its sense of waste, the ending – an act of suicide – as agonising as anything in The Wild Bunch or Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

Peckinpah’s passage through life was marked by a string of twisted and broken relationships. Quizzed on how he came to understand so intuitively the psychology of his characters in Straw Dogs, he offhandedly replied that he’d simply been married a few times. If his films are anything to by (and they are, for his was a deeply personal vision), his attitude was something along the lines of ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’. His characters are either denied love because of their stubbornness or the transcience of their lifestyle, or experience love only for it to be taken away from them, usually by the intervention of death. Even the pleasant, laconic Junior Bonner unfolds against a backstory of parental estrangement.

But then Peckinpah was an intense man. Interviews with potential collaborators were often conducted to the accompaniment of knife-throwing, the door to Sam’s office scarred with more notches than Casanova’s bedpost. A disagreement with Charlton Heston on Major Dundee erupted into near-homicide when the actor, kitted out in full cavalry regalia, drew his regimental sword and charged at Peckinpah! While viewing dailies on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Peckinpah was outraged to find that a damaged flange on a camera had rendered a week’s worth of footage out of focus; he startled cast and crew by lumbering forward, unzipping, and urinating on the screen.

A man of Peckinpah’s genius can be said, for want of a more scientific explanation of where such talent derives, to have been born with an innate sense of creativity, a spark of genius. But his temperament was formed by circumstances.

He was born David Samuel Peckinpah on 21 February 1925, David after his father. In childhood his family took to calling him ‘D Sam’. By the time he was a man it was just Sam.

David Peckinpah was a successful lawyer, upstanding citizen and strict disciplinarian. He lived by the law and the Bible. Sam’s inability, in early youth, to reconcile this aspect of his father with the man who meretriciously cross-examined witnesses on the stand, building them up to knock them down, goes some way to explaining the polarities that inform the films he would go on to direct. Likewise, while the romantic disillusionment he would so often portray was mirrored in his own turbulent relationships, it has its seeds in his parents’ marriage.

His mother, Fern Church, was a highly strung woman whose betrothal to David Peckinpah was something of a second-best, occurring on the rebound from her first suitor, an apparently dubious type. Dubious enough, anyway, for Fern’s father, Denver Church, to pay him off and see him out of town rather than accept him as a son-in-law.

Throughout her marriage to David, Fern would respond to threats to her matriarchy by complaining of headaches or nerves. Silence would descend on the house; everyone would walk on eggshells around her. Anyone behaving contrary to this, or daring to answer her back, would have David to deal with. Corporal punishment was part and parcel of Peckinpah’s childhood, administered either by the hand or a strip cut from a birch tree.

With Fern’s specialist brand of silent tension suffusing the household, it is easy to see why hunting trips into the mountains became such a strong draw for the men folk. They were a quartet: Denver Church, David, Denny (Sam’s older brother) and Sam himself. The hunting trips became such a tradition that Sam continued them throughout his adult life. Still, they were a traumatic experience initially. David had seen the development of aestheticism in his son – an appreciation of poetry and art – and he and Denver decided such unmasculine qualities needed ironing out. They took him into the high country, put a rifle in his hands and told him to be a man.

It says a lot about Peckinpah’s character that this proving-ground, this wilderness setting for his rite of passage, would be a place to which he would return, year after year.

David Peckinpah and Denver Church set themselves up as role models that Sam and Denny were expected to emulate. Denny conformed, quelling his own artistic aspirations (literary in his case) to follow his father into law. Sam took a different route. It was a journey that led from theatre to television and then to cinema. But before any of that, he made a decision that must have shocked even the machismo-laden David Peckinpah.

Just shy of his eighteenth birthday Sam joined the Marines. At Parris Island, he underwent a harsh training programme that made his father’s disciplinary excesses look like a walk in the park. The way Marines were trained during the Second World War was psychologically similar to the Vietnam-era portrayal in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Individuals were broken down, browbeaten, yelled at, punished and humiliated; then they were remoulded as a unit – a lean, effective fighting force. Peckinpah went through hell, but what he learned he would apply on film sets twenty years later. He would demand, expect and settle for no less than everybody’s absolute best. He would fire crew members indiscriminately – no warnings, no second chances. But those who were left would follow him without question and give their all.

On completion of training, he was dispatched to China. It was 1945 and the decisive bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima had ended the war with Japan. The purpose of the Marines’ presence in China was to oversee the disarmament and repatriation of Japanese troops there. Peckinpah saw the aftermath of conflict, gained experience of military procedure, and developed deeply ambivalent political views – all of which he would draw upon in Cross of Iron. He also discovered the joys of drinking and womanising. These, too, would be defining factors in his life.

His homecoming in 1946 was marked by a listlessness. His father still expected him to study law and join him and Denny in their practice. But law was conformity, and Sam wanted no part of it. He was looking for something else. He found it in the shape of the woman who would become his first wife, Marie Selland. She was studying acting. As their relationship grew, he enrolled at the same college, initially taking a history course to mollify his parents. He soon dropped out of it, his affinity for the dramatic arts proving too strong to be ignored. Marie was in love with the performing side of it, but Peckinpah’s imagination had responded to what happened before the actors stepped up on stage. Preparation, rehearsals, textual analysis of the piece they were performing: Sam Peckinpah had discovered the keystones of directing.

By the time their studies at Fresno State College came to an end, Sam and Marie had married. Marie took work, while Sam continued his studies at USC; here, too, he had the opportunity to adapt and direct plays. With the birth of their first child, Peckinpah was financially compelled to relinquish his academic lifestyle and earn a wage. His temperament made him unsuited to the nine-to-five daily grind, and his artistic impulses were still as strong as ever, so when he was offered the post of director-in-residence at a local theatre, he accepted eagerly.

The workaholic in him began to manifest here. He put in hours above and beyond the requirements of the job. Work consumed him. This, coupled with his drinking and often frightening mood swings, would eventually destroy his marriage. In his capacity as director-in-residence he had his first experience of what might politely be termed ‘creative differences’. Peckinpah wanted to direct powerful dramas by William Saroyan and Tennessee Williams. The management wanted nice, safe, inoffensive productions: drawing room comedies, or Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals. The resultant bartering, bickering, compromises and clashes of personality would recur on or behind the scenes of almost every film he made.

Peckinpah directing Cross of Iron: he drew upon his own military experience.

Long before cocaine, and while his drinking was still a social activity, Sam Peckinpah’s first addiction was to directing. And as with every form of addiction, no matter how much you get, it’s never enough. It didn’t take long for him to feel constricted by the theatre. Arranging actors on a stage had taught him the value of composition and framing, but the tableaux were static. Adapting, abridging or reconstructing extant texts had given him an understanding of structure and juxtaposition, but the words weren’t his. He needed something that was energetic and immediate, a broad visual canvas on which he could express himself. He needed something that moved.

He needed the screen.

He came to it in a roundabout manner. Some people get a foot in the door; others get their feet under the table. Peckinpah crept in through the tradesman’s entrance. In 1951, still in his mid-twenties, he took a menial job at a Los Angeles TV station. The medium was in its infancy. Ratings and advertising had yet to give the kiss of death to experimentalism. TV stations were by and large independent and willing to go out on a limb: if someone came up with an idea – what the hell! – let’s air it and see if takes. Opportunities were rife.

Nonetheless, Sam still had to start out as a stagehand.

Bearing in mind his return to television with Noon Wine following the Dundee disaster, it is a supreme irony that Peckinpah’s small screen breakthrough came as the result of his involvement with feature film production. The movie was Riot on Cell Block 11, the director Don Siegel(2). Sam was hired as ‘dialogue director’ (read cabin boy to the director). He landed the gig not through contacts at USC, friends in theatrical places or the recommendation of his bosses at the TV station, but because Denny inveigled a politico he was working for into pulling a few strings on his brother’s behalf. Consider the outraged depiction of political machinations and behind-the-scenes payoffs in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and the irony takes on a darker aspect.

Peckinpah directing The Osterman Weekend, his final film.

Still, in Don Siegel, Peckinpah found a worthy mentor. Siegel was quick to notice the younger man’s talent and encourage it. Decades later, when Peckinpah was once again in exile (this time because of his cocaine habit on Convoy) and Siegel reduced to helming the Bette Midler comedy Jinxed, Siegel had no qualms about hiring him as second unit director. Between Siegel acting once again as benefactor and Peckinpah pulling himself together and undertaking the assignment in a professional manner, he was allowed one more outing behind the camera, on The Osterman Weekend. This might not sound like much, but at least it meant that he got to go out on something other than Convoy.

Following Riot on Cell Block 11, his hands-on education in film-making progressed by degrees. Siegel hired him in a similar capacity on Private Hell 36, before giving him an altogether more tempting assignment redrafting the screenplay for Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The Siegel connection also landed him jobs on two Jacques Tourneur films, the westerns Wichita (starring Joel McCrea, who would later headline Ride the High Country) and Great Day in the Morning, as well as Seven Angry Men, Charles Marquis Warren’s biopic of slavery-abolitionist John Brown.

The rewriting that Peckinpah was permitted to do proved that he had a flair for naturalistic dialogue and an understanding of the structure and dynamics of narrative storytelling. The next step, of course, was to write his own material ... and direct it.

This meant going back to television. Again, Don Siegel played a part. CBS, who were keen to transfer the high ratings of the radio series Gunsmoke to television offered Siegel a chance to come on board. Fearing it would be perceived in the industry as a backward step, he declined, but put in a word for Peckinpah. In the meantime, Charles Marquis Warren had joined the Gunsmoke production team. Peckinpah’s associations with Siegel and Warren helped, but the quality of his writing spoke for itself. Eleven of his scripts were filmed during Gunsmoke’s first two years on air and critics were quick to pick up on his name as a guarantee of hard-edged, gritty drama.

Sometimes too gritty, as it turned out. When Gunsmoke debuted on television in 1955, the invidious tentacles of advertising were beginning to curl round the creative freedom of broadcasting – and tighten. Ratings were the bottom line. Big ratings pleased advertisers: more people watching, more products sold. TV stations were becoming reliant on advertisers to sponsor individual shows. Shows that were controversial, cynical or had unhappy endings were likely to be unpopular with audiences. If viewing figures slackened, advertisers would get cold feet and withdraw their support. To keep Gunsmoke on the air, its producers bowdlerised the darker, racier scripts (i.e. the more interesting ones). The result: mass appeal to a family audience, consistently high ratings, and mollified money-men.

Commercialism. That was how it had been with the ultra-conservative theatre management of a few years before – and how it would be with all the producers who tampered with his work in the years to come – and the result was a very frustrated Peckinpah.

True, his on-going work on Gunsmoke was providing him with a steady income, but it wasn’t enough. As much as he tried to imbue each script with his own vision of the Old West, he was hamstrung by the origins of the stories (all were adapted from the erstwhile radio episodes), as well as editorial blue-pencilling prior to filming. He wanted something over which he could exercise more control.

The opportunity came via Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theater. Peckinpah had been contributing one-offs to any number of other western anthologies, including Boots and Saddles, Tales of Wells Fargo and Broken Arrow (of four episodes written for Broken Arrow, Peckinpah had the opportunity of directing the last one, ‘The Knife Fighter’), but it was with ‘The Sharpshooter’, written for the Zane Grey Theater, that Sam’s career in television really took off. In the heyday of television, before pilots were commissioned and/or developed into fully-fledged series on the say-so of executives, a one-off drama could act as an inadvertent pilot if public or industry response were favourable. So it was that viewers were introduced in ‘The Sharpshooter’ to Lucas McCain, soon-to-be hero of The Rifleman.

Peckinpah’s hopes for the show – that he could use the character of McCain’s son as a device to strip away the myths of the western, a grittier picture emerging as the boy matures and the scales fall from his eyes – were confounded after one series by his producers (although Peckinpah was the creative force behind The Rifleman, he had only been contracted as ‘story consultant’) who inevitably opted for a toned-down, ratings-friendly approach. Friction with his producers was exacerbated when Peckinpah began to direct episodes himself. Setting the pattern for his extravagence as a film-maker, he shot more takes and demanded more camera set-ups than were conventional, pushing the budget beyond what was financially viable.

After he quit the show, he went back to writing screenplays, again for the Zane Grey Theater. This time he had Dick Powell’s assurance that if one of the scripts caught on, he would be allowed to develop it as a series and act as his own producer. This arrangement resulted, in 1960, in The Westerner, starring Brian Keith as Dave Blassingame. The character was Peckinpah’s first real anti-hero: a drifter, hard-drinking, scarred by self-doubt; a complex and flawed individual, sometimes driven by purely selfish motives, at other times capable of tenderness, his emotions underpinned by regret. In the opening episode, ‘Jeff, he suffers the frustrations of unrequited love, unable to save the eponymous saloon girl from a self-destructive lifestyle to which she has resigned herself. When he rides out of town at the end, he is every inch the loser. In ‘School Day’, he is wrongly accused of murder and targetted by a lynch mob. In ‘Hand on the Gun’ and ‘The Line Camp’, the archetypal dramatic western showdown is turned on its head, with Blassingame powerless to prevent pointless death in the former and complicit in it in the latter. ‘Ghost of a Chance’ ends with Blassingame leaving the villain of the piece to the vengeful attentions of a group of wronged women, a set-piece Peckinpah would revisit in Cross of Iron.

There were thirteen episodes in all, five directed by Peckinpah. A second series was not commissioned. Although it’s a damn shame that Peckinpah got only the one stab at it, the show was his chrysalis: he began work on it as a writer and emerged as a confident and technically accomplished director.

Peckinpah’s work for television is fascinating to examine for the glimpses it gives of the films that lay ahead. At times The Rifleman seems like an extended casting session for the rest of his career. The pilot episode features R G Armstrong and Dennis Hopper. Armstrong would notch up four film appearances for Peckinpah while Hopper, present at the outset, reappears in his last film, The Osterman Weekend. An episode called The Marshal’ again features Armstrong as well as James Drury and Warren Oates, later to reunite as two of the Hammond brothers in Ride the High Country. Katy Jurado crops up in The Boarding House’, fifteen years before her memorable turn as Ma Baker in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

The Westerner consolidated his posse: Oates and Jurado reappear in ‘Jeff’ and ‘Ghost of a Chance’ respectively, while Slim Pickens and Dub Taylor, and (behind the camera) Lucien Ballard, all make their Peckinpah debuts.

Although Brian Keith doesn’t feature in Peckinpah’s filmography to the extent of these other luminairies, he and Peckinpah established a friendship that led to the unfortunately bittersweet experience of his first movie. Keith must have thought he was doing Peckinpah the favour of a lifetime when, offered a starring role alongside Maureen O’Hara in The Deadly Companions (1961), a western produced by Charles B FitzSimons, he accepted on the condition Sam direct it. Maybe it was Keith’s insistence on Peckinpah’s involvement that stuck in FitzSimons’s craw; maybe he had overwhelming ambitions to direct; maybe he was just a control freak with a Hollywood ego. Whatever the reason, Charles FitzSimons was the first in a list spanning two decades of producers who made it their business to meddle with Peckinpah’s work. He hovered at the director’s elbow from the first day of shooting to the last, overriding his instructions on camera set-ups and dictating how all the major scenes should be staged.

Still, it gave Peckinpah his first taste of the big screen, and despite the second-rate script and less-than-ideal working conditions, his command of the medium was evident. He was soon given another opportunity. On the surface, it didn’t seem much of an improvement on The Deadly Companions: cliched script, constrictive budget. But Sam was given the chance to rewrite it. He used this creative freedom to overlay the story with personal touches, flashes of humour and moments of understated pathos. With ageing genre icons Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott on board, Ride the High Country (1962) emerged as Peckinpah’s first fully realized meditation on what would become his quintessential theme: the effect of changing times on men who belong to a different era, men whose way of life and way of doing things has become outmoded and misunderstood. But men, nonetheless, who would rather go out in a hail of bullets than go along with modernity. When McCrea and Scott face down their nemeses (younger men, superior numbers), the sentiment is clear: ‘Let’s meet ‘em head-on, halfway, just like always.’ Their final stand – against youth, against ‘progress’, against all the mistakes of the past they’ve been unable to run from – is Sam Peckinpah’s first götterdämmerung.

The shoot wasn’t entirely trouble-free – bad weather meant new locations had to be scouted – and Peckinpah found himself banished in the latter stages of post-production after spending a disproportionate amount of time in the editing suite. Fortunately producer Richard Lyons, under orders from MGM top brass to finish work on the film post haste, was perspicacious enough to maintain contact with Peckinpah clandestinely, implementing his instructions on how to put the finishing touches to it. The frequently intrusive score was beyond Peckinpah’s control and proved (no pun intended) to be the only wrong note. Otherwise, Ride the High Country is a little gem. Not that Joseph Vogel, then president of MGM, appreciated it. Disconcerted at a surreal wedding scene set in a brothel, he ordered it relegated to supporting feature in a double-bill with histrionic historical drama The Tartars. Critical reaction proved him wrong; the film was fêted, the billing eventually reversed. A slew of awards followed: the Silver Leaf in Sweden’ the Silver Goddess in Mexico, the Paris critics’ award and the Grand Prix in Belgium.

It also brought him to the attention of Charlton Heston and Jerry Bresler. Bresler was a producer working for Columbia. He was the man behind Diamond Head, an insipid adaptation of Peter Gilman’s novel, but a solid enough hit at the box office for Bresler to cast around for another vehicle for his leading man. What he settled on was a synopsis by Harry Julian Fink (later to make his name as the writer of Dirty Harry) called And Then Came the Tiger. Behind the lurid title was an epic-in-waiting. It told the story of a disgraced cavalry officer who becomes obsessed with hunting down a vicious indian war-chief. Assigned to guard a prison garrison, he recruits an army of cut-throats, bandits, rustlers and infantrymen from both sides of the civil war, and goes renegade,’ leading them further into Mexico as he pursues his quarry.

Heston saw the possibilities. Heston watched Ride the High Country. Heston knew Peckinpah was the man. Peckinpah was just as enthusiastic: he signed on without hesitation. Fink was greenlighted to write the screenplay proper. Bresler sweet-talked the Columbia money-men: big cavalry epic – big budget. Everyone was excited. Peckinpah started scouting locations.

Things started going wrong a couple of months before shooting was scheduled to start. The script that Fink turned in covered less than half of the action according to his synopsis, and it already ran to 163 pages (or two and three-quarter hours, allowing for the old rule of thumb that a page of script equates to a minute of screen time). Peckinpah was horrified. He petitioned Bresler, who managed postpone commencement of shooting for three months. Oscar Saul was brought in to lick the script into shape; he and Peckinpah worked like men possessed. Their endeavours resulted in something considerably better than Fink’s disjointed opus, but it was still far removed from a satisfactory shooting script. Despite Bresler’s reservations, Peckinpah was convinced he could pull the film together on set: it would cohere as he shot it.

But before filming could even begin, Columbia got cold feet over the kind of film they had invested in. Cavalry epic? Big budget? Not any more. A bunch of suits in a boardroom decided that it was going to be a moderately budgeted two-hour western. They summoned Bresler and put it on the line: budget and shooting schedule were to be downsized. Bresler kowtowed to his wagemasters.

In cavalier disregard for Bresler’s edict, Peckinpah led his company into Mexico and set about making the film as he envisaged it. He went wantonly overbudget and over schedule. Cast and crew members fell ill. Bresler, now siding with the suits against Peckinpah, made a location visit and tried to bully his director into a quicker, more perfunctory method of film-making: few set-ups, less footage shot. No doubt rankled at how much Bresler’s behaviour resembled FitzSimons’s, Peckinpah rounded on him, threatening that he wouldn’t shoot another frame until Bresler removed himself. Heston and his co-star, Richard Harris, stood by Peckinpah: leave Sam alone or we walk. Scared at how much more of Columbia’s money stood to be lost, Bresler beat a hasty retreat.

A further complication presented itself on set in the alluring shape of young Mexican actress Begonia Palacios, soon to be the second Mrs Peckinpah. As well as the third. And the fourth. All couples fall out; the majority make up again. Sam and Begonia took this pattern of behaviour to something of an extreme: fall out, get divorced, make up, remarry.

With their relationship in its earliest, romantic, idealised stage, Peckinpah returned from filming the now retitled Major Dundee (1965) not realising that Bresler and Columbia were ready to take their revenge on him. They waited until he had completed post-production on a two hour forty-one minute cut, then took it out of his hands, hacked it down by nearly a third, had actor Michael Armstrong Jr record a terrible voice-over track, and lumbered it with one of the most atrocious soundtracks ever composed.

When the film premiered, the critics tore it apart like vultures fighting over the newly dead. They made no allowances for Columbia’s travesty. The knives were out for Peckinpah. They stuck it in and broke it off. It was the first time they had turned against him. It wouldn’t be the last.

The stigma of Major Dundee could have been deflected had Peckinpah been able to bite the bullet on the next project he was offered, The Cincinnati Kid, and make the nobrainer that producer Martin Ransohoff wanted. As Richard Luck puts it, ‘all Sam had to do was show up on set every day, say “action”, “cut” and “print” and by the end of shooting, his career would be back on track’(3). But if ever there was a man who couldn’t bring himself to undertake banal work, no matter the industry kudos or financial rewards that might be had, it was Sam Peckinpah.

The film, as eventually directed by Norman Jewison, tells of a cardsharp (played by Steve McQueen) hustling in New Orleans against a backdrop of the 1930s Depression. The gambling is merely an excuse for the plot, and the film-makers are more interested in McQueen’s complicated romantic entanglements with an archetypal ‘nice’ girl and an equally straight-out-of-Central-Casting vamp (played by Tuesday Weld and Ann-Margret respectively). Peckinpah had no interest in these elements. He focused instead on the social and political elements of the story. Adamant that he wanted to bring the Depression from the background to the foreground, maybe even shoot the film in black-and-white, Ransohoff wasn’t having any of this and responded by firing him.

Dundee had been bad enough: the critics had turned against him. Now his standing in the industry was tarnished. 1965 to 1969 were Peckinpah’s wilderness years. He wrote scripts. He tried to get backing for adaptations of favourite novels – Max Evans’s The Hi-Lo Country and Castaway by James Gould Cozzens(4). He tried to re-establish himself. In the end, he went back to television.

The offer came courtesy of Daniel Melnick, an independent TV producer who had managed to interest ABC in a one-off drama based on Katherine Anne Porter’s Noon Wine, to be screened as part of their Stage 76 anthology series. Melnick knew from The Rifleman and The Westerner that Peckinpah was the ideal director. Bresler and Ransohoff mounted a petty little campaign to warn him off, but Melnick was resolute. Peckinpah seized the opportunity. The hour-long film he delivered was a minor masterpiece. Never mind that it was made for the small screen, the artistry and thematic depth are the equal of any of his feature films. His reputation was resurrected; the critics were back on his side again. Nominations from the Writers’ Guild and the Directors’ Guild followed. Once again, he was in demand.

Typically, though, his return to the big screen with what many would hail as his masterpiece, The Wild Bunch (1969), would be arrived at by a tortuous route. Initially, he was offered writing duties on a biopic of Pancho Villa, with producer Ted Richmond’s promise that if Yul Brynner, already signed up to play the revolutionary, approved the script, Peckinpah could also direct. Earlier in his career, before The Westerner, Peckinpah’s contribution to the Marlon Brando project The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones (adapted from the novel by Charles Neider) was deep-sixed when Brando decided to have Sam’s script rewritten(5). Now history was repeating itself: Brynner took against the screenplay (which questioned the morality of Villa’s crusade) and Peckinpah’s services were dispensed with.

The next offer came from Kenneth Hyman, head of production at Seven Arts and the man behind Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen. Keen to rush into production The Diamond Story, an action thriller intended as a Lee Marvin vehicle (one, he hoped, that would replicate The Dirty Dozen’s success), he instructed producer Phil Feldman to liaise with Peckinpah. Hyman wanted Peckinpah to rewrite the script, then direct. Peckinpah was less than impressed with the material, and he and Feldman’s attentions turned to the various properties Peckinpah owned: the rights to The Hi-Lo Country and Castaway, as well as some original scripts. Two in particular stood out: The Wild Bunch and The Ballad of Cable Hogue.

Peckinpah’s masterpiece.

What Peckinpah and Feldman liked about The Wild Bunch wasn’t so much the script itself (a sketchy affair by Roy Sickner, a former stuntman, and Walon Green) as the possibilities it presented. The story was set against the backdrop of revolutionary Mexico. After being stabbed in the back over Villa Rides (Brynner had Sam’s script rewritten by Robert Towne, brought director-for-hire Buzz Kulik on board, and the result was a melodramatic pseudo-epic), here was another chance. This time, he’d do it right.

But The Wild Bunch might well have been relegated until The Diamond Story was completed had it not been for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. William Goldman’s script was the talk of Tinseltown. Twentieth Century Fox shelled out nearly half a million for it, and assigned directing duties to George Roy Hill. Feldman realised that, with The Wild Bunch already in Peckinpah’s hands, he had a shot at producing his own blockbuster: a challenge to Butch Cassidy at the box office. If the film was put into production straightaway, they could even get The Wild Bunch out first. The Diamond Story was abruptly abandoned.

Peckinpah and Feldman worked on The Wild Bunch with fervour. Sickner and Green’s script was rewritten, something darker and more complex emerging. Locations were scouted, the cast assembled. Lee Marvin was in the frame for the role of Pike Bishop, the Bunch’s embittered leader. Hyman wanted Marvin because of their earlier hit with The Dirty Dozen; Feldman saw The Wild Bunch as a replacement Diamond Story and took Marvin’s involvement as a given. As it happened, the actor was offered Paint Your Wagon (and a paycheque for a cool million). He snapped it up, forsaking the greatest western ever made for one of the worst, and William Holden got the role.

Feldman indulged Peckinpah to the extreme, such was his faith in the project. Multiple camera set-ups captured the film’s set-pieces – the violent opening and closing shoot-outs, the train robbery and subsequent pursuit – from a variety of angles. A river bridge was built and spectacularly blown up; the river dammed upstream to compensate for its shallow waters, which would otherwise have proved perilous for the stuntmen who plunged into it. Warner Brothers, who were backing the film, would famously claim, for publicity purposes, that more rounds of blank ammunition were fired during the making of the film than live ones in the entire Mexican Revolution.

Feldman’s belief wasn’t misplaced. Peckinpah delivered a monumental work. The relationship between the two men was so productive that, with The Wild Bunch still being edited, they went into pre-production on their next collaboration, The Ballad of Cable Hogue. Things turned sour when Warners began pressing for a much shorter cut of The Wild Bunch than Peckinpah had envisioned. With his original cut clocking in at three and three-quarter hours, it was obvious that a more commercial running time would have to be arrived at. Peckinpah anticipated making certain compromises. What he didn’t anticipate was Feldman going behind his back. With Peckinpah busy filming The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), Feldman bowed to pressure from Warner executives and cut everlarger chunks, including the all-important back story of Deke Thornton’s incarceration and Pike Bishop’s ill-fated romance, bringing the film in at the two hour mark.

Peckinpah felt betrayed; his antipathy towards Feldman and Warners was very vocal and very public. Consequently, Cable Hogue was the last time he and Feldman worked together. Warners didn’t understand the film, a part-comedic/part-melodramatic little fable, and released it without a whisper of publicity. Peckinpah’s redoubled criticism of his paymasters, as well as the legal action he threatened over their duplicitous editing of The Wild Bunch, led to the cancellation of his contract with Warners. As a result, he lost out on the opportunity to direct one of the key films of the 1970s.

Deliverance would have been an ideal film for him. Four city types set off on a canoeing trip, their last chance before redevelopment alters the course of the river. Their backwater idyll turns nasty when they encounter a group of inbred hillbillies whose attitude to outsiders goes way beyond mere resentment. Beset by the forces of nature and the dregs of humanity, their holiday becomes a grim fight for survival. A character piece with terrific action scenes, the wilderness a canvas on which to paint man’s most primitive urge for survival, Sam calling the shots and the whole package wrapped up in Lucien Ballard’s expressive cinematography – it would have been something else! Peckinpah’s enthusiasm was matched by that of James Dickey. The novelist lobbied for Peckinpah as director.

William Holden in The Wild Bunch.

But with Sam persona non grata, directorial duties were assigned elsewhere. Dickey must have been as distraught as Peckinpah: with the wrong director, his novel could easily have been downgraded to a by-the-numbers actioner. Fortunately with the talents of John Boorman, Vilmos Zsigmond (Ballard’s heir apparent), a top-notch cast and some memorable banjo riffs, Dickey’s dark and complex vision got the big screen treatment it deserved. Still, as Richard Luck opines, ‘you can’t help thinking about what might have happened had Warren Oates, James Coburn, L Q Jones and John Chandler rowed off into the wilds with Uncle Sam at the tiller’(6).

Instead, Peckinpah’s next picture saw him holed up in a farmhouse in rural England, the Appalachian wilds replaced by an isolated Cornish community but the locals just as nasty. Like Deliverance, Straw Dogs (1971) has a city dweller out of his natural habitat, a gruelling rape scene (heterosexual as opposed to riverside buggery) and violent catharsis, the implications of which reverberate long after the closing credits.

Peckinpah and Dustin Hoffman on the set of Straw Dogs: Hoffman tried to have him replaced.

The film reunited Peckinpah with Daniel Melnick. The producer stuck by him as obstinately as he had on Noon Wine. Following Peckinpah’s hospitalisation, Dustin Hoffman tried to have him fired, urging Melnick to hire Peter Yates (director of Bullitt). Melnick refused to do his star’s bidding and ordered that the production be closed down until Sam had recuperated. Repaying Melnick’s faith in him, Peckinpah got it together and threw himself energetically into the project. Straw Dogs renewed the controversy over Peckinpah’s portrayal of violence. Of course, the nay-sayers overlooked the non-occurrence of it in his follow-up, the lyrical and likeable Junior Bonner (1971). Like Cable Hogue, it was the victim of studio non-comprehension: they didn’t get it, so they released it without fanfare or appropriate advertising, and even with the star presence of Steve McQueen it did little at the box office.

It did, however, land Peckinpah his next directing gig. McQueen had co-founded United Artists with Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier and Barbra Streisand. Their intent was to develop projects with more freedom than the existing studio system permitted. McQueen had bought the rights to Jim Thompson’s pulp novel The Getaway. He and Peckinpah had got on well making Junior Bonner. And the rest, to regurgitate an old cliché, is history. The Getaway (1972) is one of the highlights of McQueen’s oeuvre. It might not be top-flight Peckinpah, but it beats the hell out of most films of its ilk. And it did huge box-office. For the first time in his career, Peckinpah’s attachment to a project was commercially viable. It all bode well for his next film, a return to the western: Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973).

It turned into Major Dundee Part II. For Jerry Bresler, substitute James Aubrey. Bresler had been a producer – just one more payrollee beholden to the money-men; Aubrey was a bigger fish altogether. Aubrey was the president of MGM.

And film production was not top of Aubrey’s agenda. He was more interested in the development of an MGM hotel/casino operation in Las Vegas and cheerfully undercut the budgets of film after film in order to pump funds into it. He refused to budget PatGarrett at more than $3 million. His penny-pinching meant that the technician Peckinpah wanted on set in case inclement weather proved detrimental to the cameras was vetoed. This resulted in the aforementioned damaged-flange/urination incident. When word of it reached Aubrey, he forbade Peckinpah to reshoot the footage. With characteristic defiance, Peckinpah reshot every bit of it on the quiet.

Other problems on set paralled the Dundee farrago: sickness struck cast and crew; last-minute script doctoring resulted in weak scenes. Peckinpah’s drinking didn’t help. It has been said that he was sober for no more than four hours out of any day during filming. It shows: Pat Garrett has a washed-out, hazy look to it; characters swig from whisky bottles in every significant scene.

Things got worse in post-production. Aubrey envisaged the film as ninety minutes of gunplay. Wanting to rush-release it, he gave Peckinpah a deadline of less than three months to produce a final cut. Since most of Peckinpah’s films started out as an amorphous mass of footage that came to life during editing, a process Sam was used to spending anything up to a year on, this was effectively the kiss of death.

Peckinpah’s attempts to compromise, whittling down his hastily assembled three and a half hour rough cut to a movie of just over two hours’ duration, were in vain: Aubrey had him barred from the editing room. Pat Garrett was eventually released in a 106-minute version that retained only trace elements of Peckinpah’s vision. The critics sharpened their axes.

Frequent Peckinpah collaborator Garth Craven was still working on the editing team under Aubrey’s draconian rule when he scored a belated victory for his mentor, stealing the preview print and transporting it to Sam’s house. Realizing he had forgotten the corresponding soundtrack, he went back the following night and swiped that too. Despite the omnipresent threat of the MGM legal department, Peckinpah was able to arrange a screening some years later at his old alma mater, the USC(7).

The effect Pat Garrett had on Peckinpah can be gauged by the darkness and perversity of his follow-up, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974). A film that can only have been greenlighted by accident, it was a study in failure, impotence and self-loathing that everyone hated. It died at the box office.

A potential back-on-track blockbuster for Twentieth Century Fox, The Insurance Company, fell through when its star, Charles Bronson, refused to work with Peckinpah. Scared that Alfredo Garcia would have the same effect as Major Dundee, its critical mauling presaging an extended period of unemployment, he took the first thing that came along: The Killer Elite (1975). Not that he had any enthusiasm for the script. Staging the whole production tongue-in-cheek, the critics responded to his rubbishing of the material by rubbishing the film itself.

Still, Peckinpah retained enough clout that two major studio productions were offered to him shortly afterwards: the Dino de Laurentiis remake of King Kong, and Superman. As commercially tempting as they were, they offered no human element; no emotional core. He turned them down(8). Instead, he responded to an offer from German producer Wolf C Hartwig to direct an adaptation of a novel by Willi Heinrich. Cross of Iron (1977) was a grimly realistic war movie, epic in scope but character-driven. Hartwig, a purveyor of pornography, intended it to be his calling card as a respectable producer. He knew nothing of film-making on this scale. His budget quickly drained away. The military hardware he promised Peckinpah failed to materialise (it is one of Peckinpah’s many achievements that he managed to make three rusty old tanks look like the entire Russian army). Peckinpah stumped up $90,000 in order to complete the film.

The critics hated it. Orson Welles called it the greatest anti-war film ever made. Welles’s assessment was the more accurate.

Again, Peckinpah realized that he needed a mainstream success in order to keep him in the game. Therefore, with great reluctance, he signed up for Convoy (1978). A drinker on the scale of Dylan Thomas throughout most of his adult life, Peckinpah had by this time developed an affinity for cocaine. Throughout most of the shooting (Peckinpah exposed more film on Convoy than on any of his other films – including The Wild Bunch), he was incapacitated. Scenes were ad-libbed to the point of incoherence. Shooting went over schedule. The budget almost doubled. Pre-production was debilitating. Unable to pare the mass of footage down to anything near a commercially acceptable two hour movie, Peckinpah made no protest when EMI had him removed from the project and appointed their own editing team. After all the battles, all the editing suite lock-outs, all the interference, all the way down the line from The Deadly Companions, it was almost unthinkable: Sam Peckinpah just giving up and walking away.

A grizzled Peckinpah on the set of Cross of Iron.

This non-vocal departure could have done wonders for his career, though: EMI hacked Convoy down to an audience-friendly length, marketed it as a Sam Peckinpah film (this ploy necessitating a play-down of the director’s removal) and it was a box-office smash. There had been no behind-the-scenes skirmishes, no falling out with producers. Even the bloated budget was forgivable now the shekels were rolling in fast. But instead of re-establishing him, Convoy was his undoing. Tales of his on set drug abuse strengthened the industry view that he was a spent force. It was common knowledge that James Coburn, on board as second unit director, had called the shots on several key scenes. The Hollywood consensus was unanimous: hire Peckinpah and you’d get a drunkard and a junkie who would push your budget firmly into the red and leave you with a major post-production headache.

For all his worries over Pat Garrett and Alfredo Garcia, it was Convoy that proved to be Major Dundee revisited: Peckinpah did not work for another five years. It took Don Siegel and the aforementioned Bette Midler vehicle Jinxed for Peckinpah’s reputation to regain enough currency for another offer to come his way. The Osterman Weekend