13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

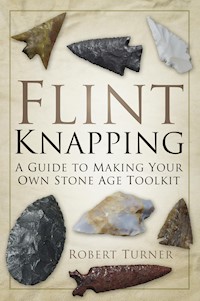

Flint knapping, which is the shaping of flint or other fracturing stone to manufacture tools, was one of the primary skills used for survival by our prehistoric ancestors. Early mankind once made and used these implements on a daily basis to hunt, prepare food and clothing, to farm, make shelters, and perform all the other tasks required for Stone Age existence. A material that has been with us since earliest times, flint still plays a part in our lives today: it is used in cigarette, gas and barbeque lighters; in some parts of Britain it is a major building material; and many of our beaches have shingle which is just flint by another name. In this informative and original guide, expert Robert Turner explains how flint was used, what tools were made and what they were made for, and provides detailed instruction of how to make them, enabling the reader to replicate their own Stone Age toolkit. Illustrated throughout, Flint Knapping is a journey of archaeological discovery through the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

To my wife, Gillian Turner, who puts up with my flint knapping, puts up with my writing and then proofreads my work for me.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

An Introduction to Knapping

1 Understanding Which Rocks to Use

2 The Conchoidal Fracture or How Knapping Works

3 How to Get Started and the Tools you Will Need

4 Making a Hand Axe

5 Making a Blade Core

6 The History of Knapping

7 Metal and Modern Tools

8 Pressure Flaking

9 Another Viewpoint on Starting to Flint Knap

10 A Further Look at How you Hit Rocks: The Levallois Reduction

11 A Core Tool and a Blade Tool

12 Let’s Make a Thin Biface

13 Let’s Make an Arrowhead

14 An Introduction to American Knapping

15 American Time Periods and Types of Points

16 Is There a Connection Between European and American Knapping?

17 UK Flint Mines and USA Flint Mines

18 Let’s Make an American Point

19 Further Knapping Techniques (Heat-Treating)

20 Summing It All Up

21 Illustrating Your Flints

Bibliography

Glossary of Terms

Plate Section

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Especial thanks to:

James Turner, my son, for the photographs in this book; D.C. Waldorf for kind permission to reproduce the drawings of the late Val Waldorf.

My thanks to the following people for help, guidance, contribution and permissions:

Bob Wishoff; Bobby Collins; Brian Thomson; Chris Chitwood; Derek Mclean; Dick Grybush; Ed Thomas; Jack Hemphill; Jerry Marcantel; Kurt Phillips; Larry Kinsella; Mark Ford; Pat Jones; Philip Churchill.

AN INTRODUCTION TO KNAPPING

If you have even a passing interest in archaeology then you will soon become acquainted with stone tools. At one time our ancestors made and used these implements on a daily basis to hunt, prepare food and clothing, to farm and make shelters and all the other tasks required for Stone Age existence.

In many parts of the world the most readily available material was flint or chert, which is SiO2 or silicon dioxide, which is why this art is commonly called ‘flint knapping’. Even in igneous rich parts of the world where obsidian, or volcanic glass, is readily available, this terminology can persist.

One of the properties of silicon is that it will carry a shock wave that allows a splitting of the material to be directed along a chosen plane. When you hit a piece of flint, a shock wave travels through the material that causes a fracture along the line of wave. If the impact is sufficiently powerful, this will follow a fairly straight line and parallel the contour of ridges already in the rock. In this way early knappers learned that they could direct the splitting of the rock to achieve a desired shape for severing, cutting and piercing tools.

Flint and chert are what is termed cryptocrystalline, meaning that there is no grain or sheer planes in the rock. The material is sedimentary and was formed in chalk and limestone when these beds were first laid down. Flint which was formed in chalk is varied in colour from white through shades of grey to black, but sometimes it can take on a brown or reddish hue, especially if contaminated by iron. Chert, which is usually a product of limestone, can be a far greater range of colours again dependent on the impurities it acquires. Some of the very best flint can be almost translucent but the rest of the material group is predominantly opaque.

Obsidian, which is a metamorphic rock formed in volcanic action, can also take on a range of colours. Unfortunately, there is no quality, knappable Obsidian found in Britain, but many other parts of the world, especially the USA, have a range of rhyolites that can take on beautiful banded and coloured forms, which make knapping a wonderful art form.

Many people want to ‘have a go’ at knapping but because they are unable to know how to start, attempts are usually a disappointing failure. The image of Stone Age man making and using stone tools is one we are all familiar with and as they were our ancestors, there is always a certain amount of attachment to those far-off days. Flint, however, is still all around us, in cigarette lighters and gas and barbeque lighters, all of which carry that small bit of the material. In certain parts of the country flint is a major building material and many of our beaches have shingle, which is just flint by another name.

Go back a hundred and a bit years and gun flints were used all over the world, most of them made in Britain. The gun flint industry was vast and in one year alone, just before the Crimean War, Turkey ordered 11,000,000 flints of various sizes from Britain. Millions were sold to the American and African markets and over a five-year period to 1885 one manufacturer alone, R.J. Snare and Co., produced 23,165,200 gun flints. It is not recorded who counted them but suffice it to say that flint is a material that has been with us since earliest times and still plays a part in our lives today.

Knapping has been carried out for millions of years from the first Hominids through Homo Erectus, Homo Heidelbergensis, and Neanderthals to Homo Sapiens or modern man. In Britain, we date flint tools back almost a million years as ‘people’ came and went between ice ages. Our modern period started some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago following the end of the Devensian Ice Age and flint tool finds are in profusion, ranging from the Upper Palaeolithic through the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age. Especially in the South of England on any fieldwalk you will be able to find worked flint of one sort or another, where flint is common. There is no evidence, currently, of a flint technology in the Iron Age. They may still have used flint tools, we just do not know.

So what are we trying to achieve in these pages? An understanding of how flint was used, the tools that were made and what they were made for, how to make the tools, and detailed instruction of how, with practice, you can replicate the toolkit of your ancestors.

Before we go further, I must make time for the dreaded Health and Safety rules which are totally necessary in knapping. Firstly, flint is sharper than steel and cuts, I am afraid, are a common occurrence. Gloves, or a single glove, are a good idea but thin leather like a golfing glove is far better than the traditional thick gardening type that can inhibit your knapping.

The most important item is eye protection and any form of glasses is a necessity. Your local DIY store will sell a cheap plastic pair of glasses for a few pounds and the outlay is well worth it. Flying bits of flint are rare but do not take the chance. Likewise, when you knap you quickly collect a small pile of shards on the ground around your feet, so do wear suitable shoes. A flint shard will go straight through a thin sole if stepped upon.

Robert Turner, 2013

1

UNDERSTANDING WHICH ROCKS TO USE

The answer to the question ‘what can I knap?’ is very simple, it depends where you live. You need to gain some information of the local geology to ascertain if anything around you will be suitable for knapping and the local reference library will provide all you need. Even if you live in an area that is poor in knapping quality rock, your house still has many things that you can practise on.

The easiest things to use are the bottom of a glass bottle, reasonable thick sheet glass (window glass is too thin) and many ceramic materials. The old kitchen sinks that you find in the scrapyards will work quite well, insulators from electric wire carriers and glass and ceramic tiles from your nearest DIY shop can also work. Some of the rocks sold for tropical fish tanks, especially chalcedony (pale blue rock), will knap and all glass-like materials are worth trying.

If you are lucky enough to live in a chalk or limestone area, flint and chert are for the picking up, but many other materials will knap. All you do is get a small sample and fracture it to see if it will take a conchoidal fracture.

Firstly then, we need to understand what a conchoidal fracture is and what it looks like. If you have ever chipped a glass you will have made a conchoidal fracture, as it will have made a small, almost circular or elliptical scar on the glass edge. The word comes from the Greek meaning shell and radiates out from the point of impact in ripples, looking very much like a mussel shell.

A conchoidal flake.

What you are seeing is the scar of the shock wave which has a pronounced first wave, called the bulb of percussion, and then a series of smaller waves as the shock progressed through the material. If the rock just breaks with a flat surface, this will not be suitable for knapping, so if you are buying, never invest in a quantity of any material until you have firstly tried it out.

Concentrating on flint, you will also find that lots of nodules are not suitable as they have been on the surface too long and have become impregnated with water, so over the years with successive freezing and thawing they have internally fractured. The thing to do is have a small hammer or a flint pebble and hold up the nodule and then tap it. If it gives a dull thud then this bit is rejected but if it rings it will probably be good, so try to knap off a small section as this will not only tell you if the flint is good but it will also show you the interior of the nodule. This testing will be invaluable as, if you find a flint supply, you can spend time and effort retrieving nodules that are very heavy, only later to find they are useless for knapping.

Flint was laid down in chalk during the last period in the Cretaceous, 85,000,000 to 65,000,000 years ago. The chalk when it was forming (at a rate of about one inch per thousand years) was, on its topmost surface, a mixture of decaying animals and plants. As sea life died it dropped to the undersea surface and rotted away, leaving behind the remnants that will become 98 per cent pure calcium carbonate, the pure white chalk that Dover is famous for.

For those who like the technical details flint is formed as follows …

During the breakdown of siliceous organisms in the top 5m from sponges, spicules, radiolarian and diatoms we get a deposit of biogenic silica and this supersaturation will precipitate at the oxic-anoxic boundary about 10m down. As the material rots it forms hydrogen sulphide H2S, the stuff of stink bombs (the rotten egg smell). The H2S rising within the sediment, from the zone of sulphate reduction, is oxidised to SO4 and liberates H+ as a by-product. The free H ions lower the pH factor and this results in a calcite dissolution and high concentrate of HCO3 ions liberated, which act as a seeding agent for precipitation of silica.

The fact that flint forms in bands reflects the cyclic nature of chalk sedimentation and short (in geological terms) pauses halt upward movement of the boundary and encourage flint formation.

Over the aeons the flint nodules will form a crust, called cortex. That requires removal to get to the pristine flint below. As the formation of flint is in a stratum that is also full of animal and plant debris, it can contain fossils and detritus material that affect the shock wave travel when knapping. If, when a flint is struck, it has impurities within it, this will deflect the fracture sideways in what is known as a step fracture. Fissures and flaws will also do this, so the only real way to determine if a flint is sound is to start knapping. Many times you start to work a flint nodule only to discard it after several strikes because you discover impurities or fossils within the flint.

The cortex on the outside of the nodule will absorb energy so it can be difficult to get a flint ‘started’ when you first strike it. Once you have broken through the cortex, then the knapping becomes much easier.

When flint forms, it is filtrated through the surface material and the further down it sinks in the formation layer the more pure it becomes, so the best flint is always at the bottom of the flint-producing layers. Early man realised this and when mining for flint would dig down through flint layers to get to the best quality. Layers of flint in flint mines are given the terminology of ‘top stone’, the layer nearest the surface; ‘wall stone’, intermediate layers; and ‘floor stone’, the best quality. This is beautifully shown at Grime’s Graves, Harrow Hill, Church Hill and many other flint-mining sites.

Very good knappable flint can be recovered from beaches but again test first to decide what is suitable.

Many chalk quarries discard flint as a nuisance when recovering chalk for cement manufacture, but be aware that flint only forms in quantity at the bottom section of the Upper Chalk so not all chalk quarries have flint. Limestone quarries can also have chert suitable for working but take heed that many aggregate quarries may look to have good material but do not have flint or chert of knappable quality. Aggregate deposits are either from ice sheet action or re-deposited by water action so they can be full of flaws – again, a test is required.

Other rocks like dolerite and basalt were used, as was granite, but they do not fracture easily and are very hard to work. Quartz has been used throughout the ages but many of these types of rocks are ground rather than knapped. There are many rocks that are knappable as follows to name a few: calcite, chalcedony, magnesite, jasper, olivine, opal or potch, orthoclase, quartzite, rhodonite, serpentine, sraurolite, onyx, uraninite, zircon and man-made ceramics. Added to this are dozens of rocks that will conchoidal fracture but are very brittle and therefore are not the most suitable choices.

We then come on to the whole group of rhyolites, dacites, novaculites, obsidians and other metamorphic rocks, some of which can be improved by heat-treating. For further information go online and use your search engine for ‘knappable rocks’.

Quality knappable material can be purchased online but it is rather expensive so learn your trade first before investing. It is fair to say that when you start knapping, for a while when you are learning, you will make a considerable amount of gravel. It takes time to become proficient, as you will see further on in this book.

2

THE CONCHOIDAL FRACTURE OR HOW KNAPPING WORKS

When you hit your first flint and fracture a flake off the nodule, you hear a sharp crack that sounds different from the noise of just hitting the stone. What you are hearing is the shock wave passing through the flint; it is travelling at several thousand feet a second and it radiates in a Hertzian cone from the point of impact.

Fracture or Hertzian cone.

The wave as it commences its travel performs a diminishing sinusoidal curve with the biggest wave first.

Sinusoidal wave.

This means that when you look at the flake you have driven off, just below the place you struck, which is called the platform, there is a distinctive bulge called the bulb of percussion. The first time you strike a flake, take a close look at it and you will see at the top, the scar where you hit the flint, lower down the bulb of percussion and then a series of smaller ripples running parallel to the bulb. Sometimes the continuing ripples are not so easy to see but by running your finger down the inside of the flake you can usually feel them. Also quite often you get smaller flake scars on the bulb itself where tiny flakes have been shattered off.

Flake.

In order to be able to describe flakes, there is a set terminology that should be adhered to. The platform end of the flake, where it was struck, is called the ‘proximal’ end and the termination or feathered end is called the ‘distal’ end. Feathering is where a flake gets thinner and thinner until it terminates. The middle part of the flake is called the ‘medial’ portion. The outside of the flake, the bit you could see before you struck the flake, is the ‘dorsal’ side and the inner face, revealed by knapping, is the ‘ventral’ side. Lastly, if the flake is seen edge-on this is the ‘profile’.

To remove your first flake you require a ‘hammer stone’, a pebble about fist size and as round as possible. A beach pebble is great but if you live in an area without pebbles, your local garden centre usually have bins of them. Literally any smooth, round, hard rock will suffice.

Using a knee pad (a bit of carpet works well) hold the hammer stone in your dominant hand, hold the lump of flint on your knee with the other hand and strike with some force near the edge of the flint. Your first attempts can be a bit of a disappointment because this is one of those skills that always looks easier than it actually is, but do not give up because you need to get some experience at just hitting flint. Keep practising until you can remove a flake every time you strike. It does not matter that all you will do is turn big bits of flint into small bits of flint; you are learning a considerable amount even if you do not think you are getting very far.

Shown for a right-handed person, ensure that the workpiece is held completely still and with the correct orientation to allow the shock wave to proceed in the desired direction. When you strike, the striking arm must not be allowed to flex, thereby elongating the arc of the strike. To assist in this, the arm is in contact with the body.

When you have removed your first flake, have a close look at the lump of flint where the flake came off. This, to give it its proper title, is now your core. You will find there is a negative bulb on the flake scar that has left a tiny overhang where you struck the core. If you are taking off delicate flakes, it is quite possible that this overhang could affect further flakes being removed from the same place. This lip therefore has to be ground off before you knap again.

Go back to your flake and look at the termination or distal end. If it tapers off to a sharp cutting edge then you have your first success. If it stops with a square abrupt end this is called a ‘step fracture’, which means that you have hit a flaw or an impurity in the flint and, finally, if you have a rolled termination this is a ‘hinge fracture’, which is caused by insufficient power in the strike.

Hinge and step fractures.

You get hinges or steps when something interrupts the shock wave, or if it does not have sufficient power to complete its proper journey; then the shock wave seeks the avenue of least resistance and exits the easiest way it can find from the flint, which is usually sideways to the path of the strike.

By now you will have a sizeable pile of bits or flakes you have struck off your nodules, all of which are extremely sharp, so we need to consider what to do with this waste material that is termed ‘debitage’. You must always clear up after a knapping session as children and animals could be stepping on your waste material, so be a responsible knapper. Debitage makes wonderful hardcore for concrete paths and foundations and your local council tip will have a hardcore area. You can put it back in the sea, if it can go somewhere that people do not (remember people are on beaches quite often with bare feet) or you can dig a hole and bury it. This last disposal method has one drawback as your debitage is now indistinguishable from archaeological debitage. A flake is a flake no matter if you struck it or someone struck it 10,000 years ago. It looks the same and flint does not alter with age. It is quite possible that some archaeologist, in say 200 years time, might dig up your cache and think it’s from an earlier age. A milk bottle buried with the flint will date it and as glass is as equally long lived as flint there will be fewer problems for future archaeological research.

I wonder how many flint tools in museums are not what they are labelled to be but rather the result of Victorians replicating earlier toolkits. There is just no way of telling.

3

HOW TO GET STARTED AND THE TOOLS YOU WILL NEED

We will now go through a detailed step-by-step process of your initial knapping sessions. The first point to make is that knapping is an art that has to be learned, so there is no substitute for practice and you must not be disappointed if you do not get immediate successes. Secondly knapping takes effort and you will get tired, so do not try to knap for extended periods, as inaccuracies will multiply after prolonged and sustained effort.

Do not do a lot of knapping indoors or in confined spaces, as breaking flint causes impact dust and will damage your health if breathed continually. Outdoors is fine but again if it’s wintertime, do not get cold, especially if you are concentrating on what you are doing and not noticing your surroundings. Putting down some sort of sheet or tarpaulin to catch the bits is a good idea and many people also have a bucket between their feet, which aids clearing up. This is a good idea, especially if you are knapping on grass, but wherever you knap be sure you clear up.

Let’s now turn to equipment. You will need a stool or an upright chair and a small table makes life more comfortable, helping you keep all necessary tools within reach. First on the list is eye protection. If you knap properly flint does not readily fly upwards, but do not take the chance. If you wear glasses they will suffice but if not, your local DIY shop will sell relatively cheap plastic glasses in their tool section for use with power tools. Gloves, or a single glove, are also recommended as the bits that come off are razor sharp but you will find that thick gardening gloves can inhibit your knapping so a thinner glove is better. Having a few sticking plasters around is a good idea but if you are careful serious cuts will not happen. If you do nick a finger the strange thing is that flint cuts do not get infected, but they do become part of the knapping scene as small cuts will happen now and then.

A knee pad is required and for a starter, to save the cost of leather, a piece of old carpet works really well. Cut a square 20cm by 50cm and lay it over your knee with the tufted side down so you are working on the carpet backing. Wear proper shoes, as the flint pieces or debitage are exceedingly sharp, and sometimes quite pointed, and will go through the sole of a thin shoe. Now you should be ready to start.

Initially it is best to start with hammer stones and we will discuss other ways of knapping as we go along. You need a range of pebbles from about 4cm up to about 10cm or 12cm; these are readily available on pebble beaches or, failing that, your local garden centre will have bins full of them for sale. They need to be as spherical as possible and not have any sharp edges. Lots of materials are suitable as long as they are hard. Flint itself is good and so are granites and most igneous rocks. You can break hammer stones so it is sensible to have a couple of each size. Which size hammer stone you use is entirely dependent on the task. Fine work that does not require a lot of force needs a small tool, while hitting a big flint nodule can take the biggest hammer stone you have.

Range of hammer stones, all as spherical as possible. The bigger the task, the bigger the hammer stone needed; for fine work tiny stones are required. Any hard rock can be suitable but if you do manage to break your hammer stone discard it, as broken edges can cut into your hand as the stone makes contact.

So let’s start. If you are right-handed sit comfortably with the hammer stone in your right hand and the pad on your left knee. Hold the material you are trying to knap in your left hand on your left knee as shown overleaf (reverse everything if you are left-handed).