Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

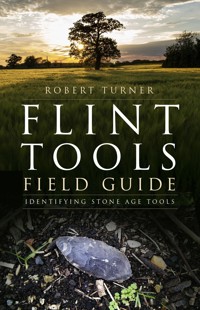

Our prehistoric ancestors used flint tools every day; they were of vital importance for cutting and scraping, used for hunting, preparing food, making clothing and building shelters, and their remnants are scattered around the countryside. Unearthing such a find is a magical moment – a direct link to events thousands of years before – but how do you identify the piece of flint you find out in the field? Is it only a lump of flint, or did it really have an important function as a tool prized by our ancestors? And how old is it, exactly? In Flint Tools Field Guide, archaeologist and flint knapper Robert Turner opens a window into prehistoric archaeology, using hand-drawn illustrations and photographs to explain how to identify tools and their uses, as well as approximate their age. This is an important insight into how people lived and worked so many years ago.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 78

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover illustrations: Landscape, courtesy of Unsplash.com; flint, courtesy of the Author.

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, Gl50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Robert Turner, 2024

The right of Robert Turner to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 712 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To my wife Gillian, without whom this book wouldnever have gone to print, and to the members ofWorthing Archaeological Society who helped.

CONTENTS

Foreword: A Field Guide to Recognising Flint Tools

Introduction

1 Basic Recognition of a Struck Tool

2 Tool Identification Information

3 Flint Tools List

4 Where to Look

5 Further Viewpoints

6 How the Tools Were Made

Glossary

Bibliography

About the Author

Type 4 Danish dagger.

FOREWORD

A FIELD GUIDETO RECOGNISINGFLINT TOOLS

A tool can be described as an object used to assist in the performance of a task. There are many examples of this in nature: an animal using a stick to winkle out a grub from a small crevasse or an otter pounding a shell with a rock to obtain a meal. Tools come in many guises but what delineates a thinking process is the actual manufacture of the tool rather than utilising a found object.

The breaking of a rock deliberately to obtain a sharp edge for the purpose of cutting appears to be the first sign of modifying an environment and goes back many millions of years. These early tools are called eoliths and were first discovered in Kent, in the south of England, by an amateur archaeologist in 1885.

The fact that eoliths were so crude led some to believe that they were actually formed naturally; however, sceptics were gradually convinced that they were man-made as more and more evidence was discovered – in particular, genuine early Lower Pleistocene Oldowan tools found in East Africa.

Oldowan tools were very basic and mainly fashioned by chipping the edges with another stone. They were used by ancient hominins (early humans) across much of Africa during the Lower Palaeolithic period, 2.6 million years ago, until at least 1.7 million years ago. These were followed by the more sophisticated Acheulean industry associated with Homo Erectus, who first appeared about 2 million years ago.

Following Homo Erectus we have a selection of hominin species including Homo Habilis, Homo Heidelbergensis, Neanderthal and, about 60,000 years ago, our species, Homo Sapiens. The final area of the Earth to be populated was the Americas following the Devensian Ice Age from 16,000 to 18,000 years ago.

Each of these groups produced stone tools but they are now identified by different names and different named periods. While the Palaeolithic appears to be a general name for before the last Devensian Ice Age, later periods tend to be named from geographical area to geographical area. For example, the USA uses Paleo-Indian; Early, Middle and Late Archaic; Early; Middle and Late Woodland; and Mississippian, while in Britain we have Early and Late Mesolithic; Early and Late Neolithic; and Bronze Age.

Another point that must be considered is latitude as ice ages have come and gone, with seven in the last million years. With these ice ages came ice sheets that scoured the land and also made huge differences in sea levels up to 140m, all of which revealed or flooded land. Where the ice did not quite reach, the land became a polar desert and thus was devoid of human life and finds during ice ages.

Stone tools can be found in most parts of the world. Some were made, used and then discarded, while others were retained; therefore, simple cutting tools and scrapers are plentiful, while others such as hand axes were retained for continuous use until worn out or broken, and so are found less frequently.

This then is the background to finding stone tools. Like finding fossils, it can be a great delight to pick up and hold something that was made thousands or tens or hundreds of thousands of years ago. Many years ago, I was working on an archaeological site on the Boxgrove horizon where we found four axe-sharpening flakes dated to 495,000 years ago. Holding something that was made and then buried half a million years ago was magic and the feeling has lived with me ever since, so I would like to share this experience.

We all take a great delight in finding things, be it at a car-boot sale or from a walk in the countryside, so this book is a guide to help with finding our past, recognising flint tools and being able to tell in what time period they were made.

INTRODUCTION

Inbuilt in all people is a liking for finding things. Haven’t we all picked up the coin we spotted on the pavement, or the seashell on the beach, or the attractive stone we saw in the countryside or field? Treasure hunting is in all of us, especially when we’re on beaches such as those in Dorset or Yorkshire where we can hunt for fossils.

We are all guilty of collecting at some stage of our life.

Everyone enjoys going to museums to view items that have been collected over the years that bring to life our ancestors: how they lived, what they wore, what they made and why their possessions were so different to ours. The further we go back into history, the greater the attraction.

In our dim and distant past we are all descended from primitive societies of hunter-gatherers and cave dwellers, and then the early farmers who signalled the beginnings of civilisation. Unless they built in stone, there are few artefacts or finds from these earlier prehistoric periods, so the older the civilisation, the less we know about it.

Natural materials like wood or bone decay and rot, leaving little trace unless conditions are conducive to preservation, and we are left with flint and other stone materials that survive virtually unchanged, so tools made by our ancestors can be found by us today.

Flint, chert, basalt and volcanic glass (obsidian) are just some of the materials called cryptocrystalline because they have no inherent structure and can pass a shock wave. This means they will split along the lines of the shock wave when struck and can be shaped with accuracy to form tools, while other stone materials like granite have to be pecked with small removals to form a shape. Obviously, Stone Age people utilised whatever stone was local and other stone materials had to be imported or traded.

A tool is something that is made to perform a specialised task, so bashing tools look different from cutting tools, as do piercing and scraping tools, with each requiring a different manufacturing process. The tools Stone Age people needed for tasks such as cutting or scraping were very easily fashioned and readily disposable, so they were made, used and then discarded, while other tools like axes were retained or kept, which may account for the numbers of each type we find. To explain this, a single strike produces a sharp blade, while to replace the edge of a dulled blade requires quite a bit of work, so it is easier to make, use, throw away and make a new one.

We can find used and broken tools by looking in places where our ancestors may have lived or for signs of tool production if we discover a manufacturing site. This book is all about how to recognise these finds, how to tell if they were man-made and to give some idea of when they were made.

How To Use This Book

After finding a flint make sure it’s clean before examining it carefully, following these steps:

1) Check its characteristics, especially the bulb of percussion and the platform (page 18).

2) Examine it closely for secondary working (retouch).

3) If it either does not have (1) or (2) or has both, it’s not a tool or debitage.

4) Try and identify it from the pictures and notes (pages 31–86)

5) Try and establish its time period from the chart (pages 25–28)

Note some tools like side scrapers are found in all periods, so more investigation will be needed, while tools like barbed and tanged arrow heads are only in the Early Bronze Age.