Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: DSP Publications

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

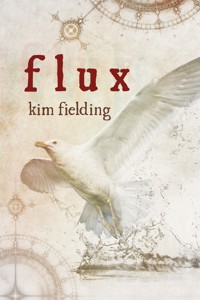

Ennek Trilogy: Book Two Ennek, the son of Praesidium's Chief, has rescued Miner from a terrible fate: suspension in a dreamless frozen state called Stasis, the punishment for traitors. As the two men flee Praesidium by sea, their adventures are only beginning. Although they may be free from the tyranny of their homeland, new difficulties await them as Miner faces the continuing consequences of his slavery and Ennek struggles with controlling his newfound powers as a wizard. Now fugitives, Ennek and Miner encounter challenges both human and magical as they explore new lands and their deepening relationship with each other.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 359

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Flux

By Kim Fielding

Ennek Trilogy: Book 2

Ennek, the son of Praesidium’s Chief, has rescued Miner from a terrible fate: suspension in a dreamless frozen state called Stasis, the punishment for traitors. As the two men flee Praesidium by sea, their adventures are only beginning. Although they may be free from the tyranny of their homeland, new difficulties await them as Miner faces the continuing consequences of his slavery and Ennek struggles with controlling his newfound powers as a wizard.

Now fugitives, Ennek and Miner encounter challenges both human and magical as they explore new lands and their deepening relationship with each other.

For Allison and Quinn, who are already writing their own stories.

chapter one

THERE WAS a pattern in the wood grain on one part of the ceiling: a knothole and some curved lines. The more Miner looked at it, the more it looked like a whirlpool, the sort rumored to swallow entire ships. He tried not to look at it at all, but that was difficult when he spent so many hours confined to the tiny compartment and when there wasn’t much else to see.

He didn’t have to stay inside; he could have wandered the decks as Ennek often did. Like Ennek, he might have found a way to help out, to coil ropes or swab decks or whatever sailors on the Eclipse did at sea. He could have kept his slave collar covered in the thick scarf his lover had given him and nobody would have thought anything of it, because the weather remained cold and blustery and clammy in a way that seeped into his bones and made them ache. And really, he should have yearned to go outside, to have open skies above him for the first time in three hundred years.

But he didn’t go above deck, at least not often, because then he would inevitably see the water tossing and foaming beneath them. And despite the angry words he muttered to chastise himself, he couldn’t face the ocean without trembling in fear.

Ennek spent hours up above, returning to their small space with hot drinks and spicy stews and hunks of dry bread, his black curls wild and his skin smelling like salt. But he seemed very understanding of Miner’s terror, and perhaps he tried to tamp down his enthusiasm over their adventure, instead drawing Miner against his muscular body and telling small tales of the day’s occurrences.

And sometimes after the sun had set, when only a few other men remained awake, Ennek would persuade Miner to climb the ladder to the top deck, and Miner would stand with his back to the railing—even though it was too dark to see the water well—and he’d breathe in some fresh air and try not to tremble noticeably.

“I won’t let anything hurt you,” Ennek told him one night in a low voice. “Not again. Thelius is… gone… and this is only water, no more dangerous than a bathtub.”

Miner had been afraid of the bathtub too, at first. He didn’t remind Ennek of that, but only nodded. “I know. I’m sorry. It’s just….”

Ennek set his hand on Miner’s shoulder. “I understand. What those bastards did to you, it was hell, and for so long…. You’re not going to get over it right away. We’ll give it time, all right? And anyway, we’ll be on dry land in less than a week, and then I promise you, we can stay far away from the ocean.”

“Thank you,” Miner replied. He knew Ennek didn’t fully grasp his fear—couldn’t. After all, Ennek had practically grown up on the water, had spent the best times of his life puttering around the bay in his little catboats or stomping about the great sailing ships as portmaster. The sea had been his lifeblood even before he’d learned he was a wizard with the element of water at his command.

“Do you want to walk around a little? I could show you how the steering works, or maybe you want to take a look at the aft rigging? It’s just a bunch of strings, but it’s so ingenious—”

“I think I’d like to return below.”

Ennek nodded. “Okay. I’m kind of worn-out anyway.”

Miner led the way back down the ladder and through the cramped corridor. Their room was actually a storeroom of sorts, and it smelled strongly of the spices that had been transported during the ship’s voyage to Praesidium. The low ceiling prevented Miner from standing up straight, and the floor space barely allowed for the mattress—so small they had to squeeze together, although neither of them minded that. Miner was happy the room didn’t have portholes. All in all, the room offered a serviceable means of escape and privacy.

As soon as they shut the door, they shed their damp clothing, piling it in a heap up against one wall. All that movement in the cramped space was awkward, and Miner knocked into the hanging lamp with his elbow, sending shadows careening crazily about. The dancing light revealed Ennek’s broad shoulders and the dark curls on his chest.

Ennek reached over to steady the lamp. He smiled shyly at Miner as they stood there in their woolen underpants. He was still timid about nudity and about the way they shared their bodies. Miner found it endearing.

“You must be going crazy locked up in here all the time,” Ennek said softly.

“But I’m used to it. Besides, I have my books. My reading’s getting much better.”

Ennek smiled again. “So why don’t you read to me tonight?”

They arranged themselves on the mattress with two or three thick blankets to keep out the chill. Miner reached into the canvas bag that contained all his worldly belongings and pulled out a volume with a slightly battered blue cover. He didn’t know whether Ennek had chosen this particular book on purpose when they’d fled the polis or whether it was the closest one at hand, but either way, Miner liked it. It contained a series of morality tales and was clearly meant for children, but Miner was able to puzzle out most of the words himself, and there were line drawings to help when he got stuck.

They leaned their backs against the wall, cushioning their skin from the splintery wood with two pillows, and Ennek snuggled in against Miner’s chest. Miner wrapped one of his long arms around Ennek and opened the book to the page where he’d left off. He’d marked it with a white-and-gray gull feather that Ennek had brought him a few days before.

“The Tale of the Cat and the M-Mouse,” he began, stumbling a bit. “There once was a mouse who lived in a great c… cas….”

“Castle,” Ennek prompted.

“Castle. The mouse lived in the scull… scullery?”

“That’s it.”

“Scullery wall, and he ate the… the crumbs of fine food that the cooks per… pre….”

“Prepared.”

“Prepared for the king. And the mouse th…. What’s that word, En?”

“That’s a tricky one. Thought.”

“And the mouse thought he was very fine indeed.”

Ennek turned his head and kissed Miner lightly on the cheek. “Your reading really is improving.”

Miner blushed a little under the praise. He continued the story, Ennek patiently helping him with a word now and then, until the mouse allowed his pride to make him foolish and the cat, naturally, ate him up. Miner was going to continue on into the next story, “The Tale of the Miller’s Daughter,” but the feel of Ennek’s skin against him proved too distracting. He abandoned the book and they made love in their quiet, sweet, still slightly fumbling way, until they fell asleep in each other’s arms.

ENNEK LOOKED slightly worried as he brought Miner some lunch the following afternoon. “The weather’s iffy,” he said. “Captain Eodore says it’s too early to tell if we’re in for a bad storm. Could be just a little bit of a blow.”

Miner nodded and wondered whether he was going to be able to eat at all with that new worry gnawing at him, making his stomach tighten and roil. But Ennek handed him a cup of grassy-smelling tea. “Drink this. It has some herbs in it that Cook says help with seasickness. Just in case. I think it has some lambs-ease in it, and maybe some spineroot. Thelius had those in his jars, and when I was cataloging, I read that they ease nausea. It’s relaxing too. Slightly sedative.”

“Thank you.” Miner took the mug and warmed his hands around it for a moment. It was thick and gray and not very well made, as if the potter were new at his craft. But it was heavy and sturdy, and he supposed it worked well enough for on board a ship. He sipped cautiously. It didn’t taste much better than it smelled, but someone had added a little sugar to it, and that made it slightly more palatable.

Ennek took a big bite of his bread, which had been soaking in the cup of meaty-smelling soup. “Look, if we do get a storm, stay in here, all right? You don’t want to be underfoot when everyone’s rushing around, and things can get pretty… exciting up there.”

“The last place I want to be during a storm is above deck.”

“Yeah, I know.”

Ennek slurped down the last of his food and rose. “I’m going back up. There’s a lot of preparation to be done, just in case. You’ll be all right down here?”

“I’m fine. I’m going to find out what sort of trouble the miller’s daughter gets into.”

Ennek bent down for a quick kiss, which eased Miner’s worries more than the tea ever could. It still surprised Miner when Ennek showed these momentary sparks of affection, and it pleased him as well, because he knew that showing how he felt didn’t come easily to Ennek.

When Ennek left, Miner read for a while. But the tea made him sleepy and he found it hard to concentrate on the words—the print seemed to squirm and crawl like insects—so eventually he gave up and tucked the book away. He briefly considered bringing out his drawing things, but then his jaw nearly unhinged itself with an enormous yawn and he lay down, inhaling the scents of Ennek and himself as he drifted off to sleep.

Pounding footsteps and rough shouts woke him. It must be the storm, he thought sleepily, not as alarmed as he might have been. Perhaps the effects of the tea still lingered. But then it occurred to him that if they were caught in a storm, he would surely feel it; and now all he felt was the normal pitch and sway of the sea, a more or less gentle motion that seemed to have settled permanently in his body.

Miner scrambled inelegantly to his feet, getting tangled up in the bedclothes as he did, and then stood there, rocking slightly, his heart beating so rapidly it was difficult to hear anything but the blood rushing in his ears. But he did hear things: more footsteps, several thundering crashes, frantic yelling, and one piercing scream.

Miner had learned to fight when he was young. His father had taught him basic swordsmanship when Miner was barely old enough to hold a weapon; everyone assumed that Miner, like his father and his father’s father, would join the guard when he reached adulthood. Of course he had, and although he never became a stellar fighter, he managed well enough with a variety of weapons and even with his bare hands.

But that had been so long ago—over thirty decades!—and Miner wasn’t the same man he had been then. The last time he had wielded a weapon was when, overcome with rage and stupid grief, he had tried to assassinate the Chief, the father of his dead lover, Camens. The Chief had survived and Miner had been punished, and now he was weak and scared and unarmed.

So he simply crouched uncertainly in his hiding space, much like the mouse in the story he’d read the night before. But the mouse had been eaten by the cat, and now loud voices resounded in the passageway outside Miner’s room. The voices were calling to one another in a language he didn’t recognize, something guttural and consonant-rich. Miner looked around the small cabin frantically, searching for something he might use to defend himself.

But before he could think coherently, the door crashed open. Two men crowded through the opening. They were tall and wiry and wild-eyed, with dark beards tied up in knots and strange, colorful clothing. They carried swords, and they looked surprised to see him.

One of them, the one with the billowy scarlet shirt, shouted something unintelligible at Miner.

Miner stood as straight as the low ceiling permitted and tried not to appear terrified. “I don’t understand you,” he said. It was the first time he had spoken to anyone but Ennek or Thelius in three hundred years.

The man growled something at his companion, who jabbered excitedly back. They both looked at Miner again, this time more slowly, and their lips curled up into smiles as they focused on Miner’s neck above the blue-green sweater he wore: at the heavy slave collar, permanently attached.

“Come here!” demanded the shorter of the two men, whose shirt had broad vertical stripes of emerald and gold. His accent was very thick.

Miner took a step backward, which meant he was pressed up against the wall. “Bugger off,” he said. And then, because he felt like he had nothing to lose at this point, and because he was horrified to think about what had become of his lover, he yelled, “Ennek!” But there was no answer. Miner ducked and tried to slip past the men, knowing it was hopeless but preferring a quick death to the alternatives. But these men were well practiced at such maneuvers, it seemed. The red-shirted one slashed at Miner’s upper arm, not very deeply but enough to hurt, causing Miner to instinctively duck away. And when he did so, the man in the striped shirt caught him, dropping his sword so he could hold Miner’s arms behind his body. Miner squirmed and kicked. He had a moment of savage glee when his bare foot connected with Red Shirt’s groin and the man grunted in pain and doubled over. But then Stripes locked a strong arm around Miner’s neck, choking him, and Red Shirt recovered enough to stick the tip of his blade directly underneath Miner’s left eye.

“No move!” said Stripes, letting go of Miner’s neck. Miner remained motionless as he listened to Stripes rustling around, out of his line of sight. Then Stripes seized Miner’s arms and tightly bound his wrists behind him with fabric. Red Shirt sheathed his sword and, with a savage grin, brought his knee up between Miner’s legs. Miner collapsed and then lay on the floor, retching miserably.

The men laughed and hauled him to his feet. With one of them in front and one behind, he was dragged and pushed down the passageway toward the ladder. Additional bearded men in gaudy colors squeezed past, their arms full of boxes; one of them elbowed Miner in the side and cackled excitedly before his colleagues urged him forward.

They had to pull Miner up the ladder by his armpits, and as soon as he was above deck, they threw him down. He rolled to his knees, groaning, and looked around.

Much of the noise had abated; the fight was over. The ship’s crew were seated in a huddle on the deck, wrists tied behind them. A few men—one in purple, one in sky blue, and one, surprisingly, in white—stood guard over the crew, swords swinging loosely in their hands. More of the pirates hurried back and forth, carrying boxes and bundles to the railing and tossing them to men who waited on a ship tethered alongside the Eclipse. The pirates were jovial, shouting and laughing and singing snippets of songs.

Miner turned and twisted on his knees, frantic for any sign of Ennek. His heart leaped into his throat when he saw three bodies alongside the railing, each sprawled in a puddle of blood, unmoving. He couldn’t see their faces. One of them had Ennek’s build—broad and not very tall—but the unmoving man’s head was obscured by the torso of another of the victims. He was coatless, and his rough brown shirt was identical to those Ennek and many of the sailors wore. It was impossible to tell the man’s identity.

“Ennek!” Miner shouted, earning a heavy blow to the head from Red Shirt. Knocked off balance, Miner fell; when he righted himself, he saw Captain Eodore among the captive sailors, sadly shaking his head and then gesturing with his chin at the railing opposite the pirate’s ship.

No! Miner refused to accept that. “Ennek!” he called again, his voice breaking.

Red Shirt hit him again, harder, and this time Miner stayed down. The rough planks were wet and the splinters dug into his cheek. “He’s gone, son,” the captain said.

After that, things became fuzzy and sounds were muted, as if Miner were watching the ships from very far away. He could barely feel it when he kicked out at any pirate who came within range, when his foot connected with shins and knees but not hard enough to do any harm, when Red Shirt dealt him a third blow to the head and then used a length of rope to bind Miner’s ankles and tie them to his wrists.

Some immeasurable time later, a particularly large pirate with a bald head and complicated beard grabbed Miner and heaved him onto his shoulder. He began to stride toward the railing.

“No!” Captain Eodore called. “We surrendered and you agreed not to harm any more of my men. Take the blasted cargo but leave him be.”

“He not you man,” replied one of the pirates, this one slightly older than the others and wearing a black shirt with large silver buttons. “He slave.”

“No, he’s a free man now. Let him go!”

The pirate pointed at his own neck. “Slave. Cargo.” Then he said something to the man who was carrying Miner, and the man continued walking until he reached the railing.

As the pirates handed him precariously over to their comrades on the other ship, Miner wasn’t even afraid of the gray water beneath him. In fact, he wiggled as best as his bindings allowed, hoping he’d squirm free and fall into the ocean and drown. At least then he’d be joining Ennek in the sea’s cold embrace.

But he didn’t get free, didn’t fall, and soon his captors dropped him unceremoniously to the deck of the pirate ship among the piles of their other loot. Someone grabbed his knees and dragged him away from the railing. His sweater bunched up against his chest, and Miner buried his face in it. It smelled of Ennek, who had given him the sweater as a gift. It was warm and soft and finely made, and it must have cost a fortune. More than that, it was deeply symbolic. The afternoon Miner had received it, Ennek had blushed and smiled after Miner pulled it on. That was when Miner had begun to believe that Ennek truly cared for him.

Ennek had loved him, in fact. Miner knew that now. Ennek had risked everything, had given up his entire life for Miner’s sake. And look where that had gotten him—dead at the bottom of the sea. As dead as Camens, the only other man Miner had ever fallen for, the man who was also a Chief’s younger son and who had been executed at his own father’s orders.

Miner vowed that as soon as he could manage it, he’d be dead as well.

chapter two

IT SEEMED to take the pirates a long time to unload the cargo from the Eclipse and bring it on board their own ship. Perhaps they weren’t in any hurry with the Eclipse’s crew subdued.

Miner had heard stories of pirates back when he was a guard, and he knew wise captains would hand over their goods instead of risking death for all. Sometimes it meant financial ruin, but in most cases the shipment was insured. And the pirates themselves rarely used more violence than necessary, because if they did, the polises would gather warships against them or, more simply, place tempting prices on their heads. When Miner was very young—perhaps seven or eight—all of Praesidium had been humming with news about a pirate named Ran Ao Liu who had been terrorizing ships all up and down the coast. Several of the polises had, for once, set aside their differences and promised a bounty large enough to make an entire ship’s crew incredibly wealthy. Many merchants had abandoned their regular shipping routes and taken up arms, and Ran Ao Liu was caught within months. His crew members became bond-slaves in Praesidium and Olicana and Vinovia, but Ran Ao Liu himself was executed painfully in front of cheering crowds at the Keep. Miner’s father had been there to see it but Miner, thankfully, had not.

Miner didn’t know whether methods of managing pirates had changed much over the past centuries, but he had the feeling they hadn’t. The small part of his mind that wasn’t completely numb was pleased about that, because Captain Eodore had been kind to him and Ennek and, even after seeing the collar on Miner’s neck, had tried to save him. Miner hoped the captain came to no harm.

As for himself, Miner no longer cared what happened. His limbs were cramped from the uncomfortable manner in which he’d been bound, his head ached from the repeated blows it had received, and his arm stung from the shallow slash of the blade. But all of those pains were trifles compared to the tearing agony in his heart.

He’d only just gotten Ennek, and now Ennek was gone. Everything else was immaterial.

The sky had grown dark by the time a group of pirates took any notice of him. By then, they’d stowed most of the stolen goods below the decks, and he could hear some of them off somewhere in the ship, drunkenly celebrating their victory. But four of them remained to loom over Miner, rumbling and spitting at one another in their strange tongue. He now knew how a steer must feel when taken to market.

After a while one of the men—his old friend Red Shirt—hunched down and cut the rope that attached Miner’s ankles to his wrists. Miner groaned as the men straightened his bent legs and then twisted him around until he was flat on his back, his arms still tied uncomfortably behind him.

“How many old you?” asked one of them. The one with the black shirt who, Miner suspected, was the captain.

Miner didn’t answer at first, but then Red Shirt kicked him savagely on the bicep, just where the sword had cut him. Miner hissed and then set his jaw. “Three hundred and twenty-six,” he said, more or less accurately.

The captain frowned, clearly trying to translate the numbers in his head. When he finished his calculations, his scowl deepened and then he kicked Miner as well, aiming for Miner’s side instead. “How many?” he demanded.

What difference did that make, Miner wondered. Perhaps it affected his sales value. “Twenty-six,” he said.

That made the pirates jabber at one another for several minutes. Then the captain looked down at him again. “What you bad?”

Miner stared at him blankly.

More slowly and very loudly, as if Miner was some sort of dim child, the captain repeated, “What you bad? You slave. Why?”

Oh. “Treason,” Miner replied.

He wasn’t surprised when the captain frowned again. “What?”

Miner sighed. “Treason. I… I tried to kill the Chief.”

That produced an animated reaction from the pirates, although Miner wasn’t certain whether they were angry or impressed. In any case, they dragged him across the deck until he was sitting near one of the masts. One of the pirates trotted away and came back a few moments later with chains in his hands. They cut the fabric that bound Miner’s wrists—he saw with a sharp pang that he’d been tied with one of Ennek’s blue socks—and instead brought his wrists forward and clapped them into irons that allowed him to separate his hands by only a few inches. They hobbled his ankles as well, although the chain there was long enough that he could have managed a halting walk. Red Shirt ran a longer chain from Miner’s wrists and around the mast itself so he would have a few feet of movement. Not enough to reach the railing, yet enough to see the waves below.

Another of the pirates—this one hardly more than a boy and with his beard barely sprouted—dropped a metal bucket next to Miner and, with a series of gestures, made clear that it was for Miner to relieve himself. The youth also plopped a blanket into Miner’s lap. It was moth-eaten and ragged and crusted with the gods-knew-what, but at least it was thick and warm.

After several more minutes of unintelligible discussion and a few prods of their boots, the pirates went away. A few men remained above deck (the night watch, he supposed) but they left him alone. He collapsed onto his side and huddled under the reeking blanket and closed his eyes, hoping he’d never wake up.

BUT HE did wake up, of course.

Several times over the course of the night, in fact, as he shivered on the damp planks and tried to cushion his sore head on his uninjured arm. He would eventually fall back asleep, but then he’d dream of Stasis, and there was no Ennek to soothe him out of those nightmares. Or he’d dream of Ennek instead, floating beneath the waves, his eyes an opaque white, his mouth open in a final silent scream, his curls floating like tendrils of seaweed.

He gave up on sleep altogether when the sun rose. Several of the pirates wandered over to stare curiously at him, but when one of them reached over to touch him, another man with an air of authority yelled at him, and he backed away, grumbling. Miner was forced to use the bucket with a laughing audience, and he drank the cup of tepid water the boy from the previous night brought him, but he refused to eat the cold, lumpy porridge. The boy yelled at him about it for a few moments, then shrugged and took the bowl away.

Mostly Miner hunched against the mast, staring blankly at nothing. If he moved even a little, his chains clanked loudly.

The pirates seemed sluggish that morning as well. Too much drink the night before. Or maybe they were always like that, spending long periods of time at the railings with mugs of hot tea or lazily sitting around carving shapes out of chunks of wood or, in the case of two of the men, knitting complicated sweaters from wool dyed bright orange.

Later the boy appeared again, this time with a crust of bread and more water. Again Miner drank—his tongue felt rough and furry—but he wouldn’t reach out for the food, and when the boy dropped it in his lap, Miner kicked it away. It rolled across the deck and then under the railing. “Fish food now,” Miner said to the uncomprehending boy. “Like my Ennek, you son of a bitch!”

He leaped to his feet and lunged for the youth, but the boy simply hopped backward, just out of reach. Miner jerked at his chains, and although he knew on some level that it was useless, he couldn’t help himself: his rage and grief made him roar and struggle until his wrists were bloody and his body exhausted. He’d accumulated quite a crowd by then—not that it mattered—and he collapsed very suddenly and hid as much of himself as he could under the blanket.

He might not be able to stop the pirates from hearing him sob, but at least they wouldn’t see his face.

AROUND MIDAFTERNOON the ship began to pitch. He pulled his head out from under the blanket and looked cautiously around. He hadn’t noticed the sky earlier, but now it was hard to miss: charcoal clouds piled ominously above, the sun blotted out so completely it was almost dark as night.

The pirates’ lethargy had vanished and now they rushed about, furling sails, securing anything that could move, coiling and uncoiling ropes in some pattern he was sure had purpose, although he couldn’t fathom what.

The temperature had dropped, and although it was not yet raining, Miner fancied he could smell fresh water. A stiff wind made the pirates’ billowing clothing flutter and snap.

The waves must have intensified, because now even these seasoned sailors were having trouble keeping their footing. They staggered here and there with faces drawn tight with worry, paying Miner no mind at all.

The first raindrops pattered against the deck. They were fat and cold, and although Miner pulled the blanket over his head and he still wore Ennek’s sweater, the wetness very swiftly soaked him to the skin, making him shiver violently. His stomach lurched and rolled, and he was very glad he hadn’t eaten anything that day. But he wasn’t afraid. If the worst has already happened to you, what is there left to fear?

The rain swept across the ship in sheets, and Miner kept his head down. The sea grew rougher and the ship creaked and groaned in protest. The pirates ran around even more frantically, their shouts torn away by the wind. Somewhere something snapped with a blast like cannon fire, but Miner twisted his body and wrapped his arms around the mast to keep himself from sliding too much. He lost his grip on the blanket and it flew away. He barely noticed—he was vomiting up bile and trying hard to breathe properly in the downpour.

The ship’s bow rose high into the air, sending everything that wasn’t tied down skittering and rolling to the stern, and then the ship dove downward. A wave crashed over the railing, and for a moment Miner was certain he would be washed out to sea, but the chains held him fast. Perhaps some of the pirates weren’t so fortunate—he thought he heard an anguished cry.

Miner had barely regained his breath when the ship yawed violently to starboard, the deck at such a steep angle that he was nearly hanging from the mast by his wrists. A truly horrible sound came from below decks, a sort of inanimate screech, and just as suddenly as it had tipped, the ship righted itself. Miner swung back into the mast, smacking his sore head. His hands were twisted and trapped beneath him, and despite the din of the storm, he heard the bone in one wrist snap. No pain accompanied it, not yet, and perhaps he’d be dead before he even felt it.

Another wave came over the railing. He didn’t catch hold of the mast quickly enough, and this wave sent him across the deck as far as his short chains allowed. When it receded, he was left flopping on his back like a fish. He rolled onto his belly and began crawling back, but there was a new wave, and then another, until he was gasping desperately, certain he was going to drown.

But either the repeated blows to his head or the lack of oxygen must have affected him, because it seemed as if the rain stopped all at once, like someone turning off a faucet, and the wind stilled, and the ship completely stopped. Then an enormous wave rose over the railing, its sides as sleek as glass. A man dressed in tattered rags stood atop that wave like a sea god, his arms outstretched, his hair in dark ringlets, his mouth opened in a roar of fury.

Ennek.

The wave crested the ship, depositing Ennek as gently as a mother might her child. Ennek looked about, and when his eyes caught the sodden, miserable heap that had once been Miner, Ennek screamed again. He rushed forward and knelt beside Miner’s body, rolling him onto his back and searching his face. “Miner? Gods, are you hurt?”

Miner smiled woozily up at him. It was kind of the gods to let him meet his death with such a good hallucination. It was even better when he realized he could feel Ennek’s hands on his cheeks, Ennek’s skin dry and fever-hot. “I loved him,” Miner said, because those seemed like good final words.

Ennek shook his head and tugged at the chain that bound Miner to the mast. Miner hissed when the movement jostled his wrist, sending up the first bolt of pain.

“I’m sorry. Gods, I’m so sorry. I promised I’d keep you safe.” As he spoke, Ennek ran his fingers gingerly over the manacles. He muttered a few words Miner didn’t understand, and then swore. “Damned metal. So much harder to move than water, even when it’s not enchanted. Hang on while I unfasten the locks.” He mumbled again and the cuffs clicked open. Miner couldn’t help but let out a small cry when Ennek removed them, again shifting the broken bone.

But Ennek hardly seemed to notice. He bent over Miner’s feet and repeated his incantation—if that was what it was—and the ankle hobbles came loose as well. Then he looked anxiously into Miner’s eyes. “Can you walk? We have to go. The ship’s sinking.”

Miner nodded dumbly and Ennek helped him to his feet. Miner had to lean on him as they made their way across the deck. How could he lean on a hallucination? A dying mind plays strange tricks, Miner decided. But they continued aft and to the side, and then Ennek helped Miner clamber over the gunwale into a tiny boat that was tied there. Miner huddled on the floor of the little boat as Ennek untied some ropes and then climbed in himself. “Can you help me at all?” he asked Miner, pointing at the hanging end of a rope.

Miner blinked at him in confusion.

“I need you to help me lower this thing. Just pull on the rope.” Ennek sounded as if he were trying to be patient and not doing very well at it.

Miner leaned over and grasped the rope with both hands. He yelped as his wrist sent a sharp blast of pain, and then he tried to tug one-handed. It didn’t work very well, but somehow he and Ennek managed to get the vessel lowered until it was bobbing in the unusually placid water. Miner saw then that there was a great breach in the hull of the pirate ship, and the sea was lapping gently inside. Had the surface of the ocean been moving as it normally did, water would have been rushing into the ship’s belly.

Ennek detached their little boat from the ropes and, moving quickly and efficiently, assembled a single mast and sail. He frowned in concentration and a puff of wind made the triangle of fabric swell. The ocean began to move again, and Ennek guided the tiller until they were scudding swiftly away from the pirate ship. Rain began to fall again, but softly, like a gentle spring shower.

When they were far enough from the big ship that it looked like a harmless toy, Ennek let go of the tiller and stood. He faced the pirates and slowly lifted his arms until his hands were straight above his head. His jaw was tightly set, and his eyes—gods, his eyes looked like seething whirlpools.

As Miner watched, entranced, a towering wave formed on the horizon. It was taller than the Keep and just as ominous. It rushed toward the pirate ship and then, with a crash that was thundering even from a distance, crested over it.

It took a few minutes before the ripples reached their little jolly boat, and with barely enough force to rock their vessel a little. Miner strained his eyes, but there was no sign at all of the pirate ship.

chapter three

IT WAS beginning to dawn on Miner that he might truly be sharing the boat with Ennek and not a mirage.

For one thing, as soon as the pirate ship was gone, Ennek collapsed to his knees—nearly tumbling over the side of the boat as he did—and vomited several gallons of seawater back into the ocean. When his stomach was empty, he remained slumped over the side of the boat, motionless and very pale.

For another thing, Miner felt awful. His broken wrist sang with pain, his stupid head pounded, and he shivered with cold. Even the cut on his arm, which he’d almost forgotten about, stung.

Surely if he were dying and imagining a heroic rescue by his resurrected lover, he wouldn’t also imagine retching and discomfort.

Moving slowly and carefully to avoid jostling the boat, he worked his way over to Ennek. Very cautiously, he reached out and settled a hand between Ennek’s shoulders. He was relieved when he felt a solid body. “Ennek?” he whispered.

He received only a muted groan in reply.

It was awkward to maneuver Ennek in the cramped space, especially with Miner’s injured wrist, but he shifted the inert body until Ennek was seated, leaning back against one of the plank seats. His head lolled down against his chest, and Miner lifted his chin to get a better look. Ennek’s eyes were bloodshot and unfocused, and although it was hard to tell in the dimming light, Miner thought there was a greenish pallor to his face.

Ennek’s navy coat was gone, his brown shirt in tatters. Miner gasped when he examined his lover’s chest: a long, jagged scar coursed from sternum to navel. Its edges were red and inflamed-looking, but the wound was closed. Miner had been stroking and licking that chest just two nights ago, and the skin had been unblemished.

Ennek shuddered violently and began to shiver even more than Miner was. Miner gave the rest of his body a cursory inspection—shredded trousers and no shoes or socks, but no other obvious damage—and looked around for anything that he could use to warm them. He sighed with relief when he found a canvas bag tucked into the bow. It proved to contain a single thin blanket, a small dagger in a leather scabbard, and a book of matches in an oilcloth bag. Miner tucked the dagger into one of his boots and stuck the matches in his trousers pocket.

He shifted Ennek around so he lay at the bottom of the boat, curled on his side. It was a very tight fit, but Miner managed to cram himself next to Ennek. He realized the blanket wasn’t large enough to cover all of his lover’s body, so after a moment of indecision, he stuffed Ennek’s bare feet into the emptied canvas bag. Then he pulled the blanket up and wrapped his arms tightly around the big body next to him. The bench seat above them shielded their heads a little from the sprinkle of rain.

It was strange. Now that Miner was free of the pirates, now that he knew Ennek had somehow survived, now Miner was afraid. He supposed that was almost a good thing—it meant that he once again had something to lose. He should have been heartened. But adrift at sea with no food or fresh water or real shelter, and with Ennek unconscious, all Miner felt was scared and exhausted. He pressed himself against Ennek as tightly as he could and fell into a deep and dreamless sleep.

ENNEK WAS still dead to the world when Miner awoke.

The sun had risen again and the sky was a cloudless blue. The sea was calm and, to Miner’s delight, the air was slightly warm. Not hot, but balmy enough that he and Ennek no longer shivered, and he had some hope that their clothing would dry. Unfortunately his tongue felt thick and furry, and he had no idea where they were, bobbing peacefully along on the featureless expanse of water. The sail hung limply in place. The hull sheltered two pairs of oars, but he wouldn’t be able to row with his broken wrist, and in any case, he hadn’t a clue which direction to head.

Every time he moved his arm, his wrist hurt him anew. The flesh was badly swollen and ringed with purplish bruises; his hand felt stiff and clumsy. At least it was his left. He sat up and did a more careful inventory of the boat, finding a loose bit of wood that used to support one of the seats. He pried at it with the dagger until it broke free, and then with a great deal of difficulty, he tore a strip of fabric from his undershirt and used it to tie the makeshift splint to his lower arm.

And then he waited.

He checked on the other man every now and then, but Ennek continued to lie there unresponsively. It must have been the magic, Miner realized. Strong magic always wears him out and makes him ill. Although Miner wasn’t certain exactly what Ennek had done the previous days, or how, it was clear he had invoked his wizard powers.

For hours and hours, nothing happened. Miner couldn’t tell whether they were floating in one place or whether the current was taking them somewhere. He saw no landmarks at all; simply the gentle green swells of the water and, above, the flawless blue of the sky. There were no signs of life, no real movement other than the sun’s slow crawl. Ennek didn’t stir. Miner hadn’t eaten for two days, and his empty stomach joined his panoply of aches.

But as Miner sagged dispiritedly against the boat’s side, untangling Ennek’s curls with the fingertips of his good hand, two things happened. First, a bird flew overhead. It was too high for him to be sure, but he thought it might be a gull. That was heartening—Ennek had told him gulls rarely ventured far from land and sailors often kept an eye out for them as a sign that they were near to shore.