Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: DSP Publications

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

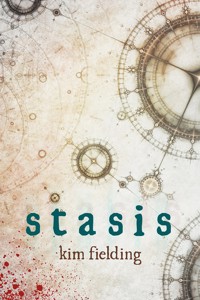

Ennek Trilogy: Book One Praesidium is the most prosperous city-state in the world, due not only to its location at the mouth of a great bay but also to its strict laws, stringently enforced. Ordinary criminals become bond-slaves, but the worst punishment—to be suspended in a dreamless frozen state known as Stasis—is doled out by the wizard and reserved for only the most serious of traitors. Ennek is the youngest son of Praesidium's strict Chief. Though now a successful portmaster, Ennek grew up without much of a purpose, unable to fulfill his true desires and always skating on the edge of the law. But he is also haunted by the plight of one man, Miner, a prisoner for whom Stasis appears to be a truly horrible fate. If Ennek is to save Miner, he must explore Praesidium's deepest secrets as well as his own.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 350

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Stasis

By Kim Fielding

Ennek Trilogy: Book One

Praesidium is the most prosperous city-state in the world, due not only to its location at the mouth of a great bay but also to its strict laws, stringently enforced. Ordinary criminals become bond-slaves, but the worst punishment—to be suspended in a dreamless frozen state known as Stasis—is doled out by the wizard and reserved for only the most serious of traitors.

Ennek is the youngest son of Praesidium’s strict Chief. Though now a successful portmaster, Ennek grew up without much of a purpose, unable to fulfill his true desires and always skating on the edge of the law. But he is also haunted by the plight of one man, Miner, a prisoner for whom Stasis appears to be a truly horrible fate. If Ennek is to save Miner, he must explore Praesidium’s deepest secrets as well as his own.

For Dennis, who cheered me on.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Mabel Marsters for reading my draft and giving me helpful comments and to Karen Witzke for her eternally patient assistance. My family and friends may have thought I was crazy to try to write a novel during the single month of November, but they were also very supportive and tolerant of my (temporary) insanity. I’m grateful to the NaNoWriMo organizers for giving me the motivation to write this. And special thanks to all of you who have read my writing and encouraged my muse with your kind and encouraging comments!

Prologue

THIS FAR down, he didn’t so much hear the waves as feel them patiently pounding against the stone foundations, rumbling and crashing without rest. It was disconcerting. Ennek felt as if the building could give way any moment, tumbling him and everything he knew into the unforgiving brine. At the same time, though, the battering of the sea comforted him, because it was as if the ocean was alive. Certainly it seemed more alive than the body now stretched before him, pale as marble, suspended in a webbing of ropes.

Ennek stood next to the wizard, Thelius, who ran his fingertips over the arm of the inert man. It reminded Ennek of the way his father, the Chief, would stroke absently at his big oak desk, worrying at many decades’ worth of gouges and scratches and dents. Thelius’s motion made Ennek’s stomach churn uncomfortably, and the Chief noticed and scowled at him. But Thelius only inclined his head a little and kept on speaking.

“So you see,” the wizard said, “they remain like this until their sentence is completed.”

Ennek’s brother lifted his hand as if he meant to touch the prisoner, then let it drop.

“Oh, it’s quite all right, Larkin. Feel if you like.” When the Chief’s older son didn’t react, Thelius gently grasped Larkin’s large hand in his bony one and set it on the prisoner’s unmoving chest.

“It’s cold,” Larkin said in a near whisper.

“Yes. They remain at room temperature, as their hearts no longer pump blood through their bodies.”

Ennek had taken a half step back, as if he might be forced to touch the man as well. “Do… do they dream?” he asked.

The Chief made a rumbling sound of disapproval deep in his throat, but Thelius only shook his head. “No, young man, they do not. They’re not asleep. They don’t breathe, they don’t eat or drink, they don’t age, they don’t sense anything around them, and they don’t think. It’s as if they are frozen in a single moment, you see?”

Ennek nodded, but his stomach felt no better, especially when Thelius’s fingers made another proprietary little motion across the white skin.

Larkin’s hand was still on the man’s chest. “How long has he been like this?” His voice was calm, almost disinterested, but Ennek knew his brother well and could tell by the slight flush in his cheeks and the way his breathing had become a little too rapid that Larkin found the concept of Stasis interesting, exciting even.

“This one has been here for slightly over seventeen years. He has thirteen more years remaining.” Thelius’s dry voice crackled like old sticks.

“And when he… wakes up?”

“Then the world will have moved on, beyond whatever foolish ideas he was trying to spread. He’s been forgotten already, I’m sure. And I’m certain the Chief will find an appropriate position for him, some way for him to repay his debt to society.”

The Chief nodded gravely at this.

“How many are there?” Larkin asked.

“Not many, not anymore,” the wizard said. “Only a score. In times past, when things were rather more… chaotic… traitors were much more common. But most of them served their sentences and were released many years ago. As you know, under wiser leadership, treachery is rare.” He inclined his head a little at the Chief, and the Chief blinked back. “I’m quite certain that when it is your own turn to take the office, you will be a strong Chief as well.”

“Thank you,” Larkin said, clearly pleased by the compliment and, perhaps, even more pleased when the Chief did not contradict his wizard’s praise.

The four of them stood for several moments, looking down at the prisoner’s bare body. Ennek wondered whether he’d been that skinny before or if he’d become that way under Stasis. He’d never seen a grown man naked before and now gazed with frank curiosity at the man’s genitals. He wondered if they all looked like this, shrunken and vulnerable.

“What’s the longest any of them have been here?” It took him a second to realize the voice asking the question was his own. He hadn’t intended to speak.

Thelius gave him a long look, but Ennek couldn’t make out what the man was thinking. Finally Thelius said, “One man has been here for nearly three hundred years.”

Larkin gasped. Maybe Ennek did as well. “Why?” he said.

Thelius shrugged. It was an odd gesture on him, like watching a ladder unfold. “I suppose he did something particularly egregious. I don’t know. His sentence is one thousand years.”

Ennek tried to imagine what it would be like to awaken after such an unimaginably large amount of time. For him, just the stretch from one New Year to the next seemed like an eternity. He shuddered, catching another angry glance from the Chief.

“Can we see him?” Larkin asked eagerly. “The one who’s been here so long?”

Thelius and the Chief exchanged looks. It was the Chief who spoke. “No. This is enough. You both have studies to return to, especially Ennek, who shouldn’t have been here at all.”

Ennek bowed his head, wondering if he’d face some punishment for begging to come along. But he’d known that if he didn’t accompany Larkin now, he might never be allowed down here. After all, he wasn’t the heir. He had no need to know what was going on Under.

Almost regretfully, Larkin took his hand off the man. Thelius did not, however. He gripped the bony shoulder tightly enough to make Ennek wonder if the prisoners in Stasis could bruise.

The Chief began walking toward the door of the cell. “Come on,” he ordered. “I have work to do.”

They followed him down the stone corridor, first Larkin and then Ennek, with Thelius bringing up the rear. Their boots clomped and echoed, and the gaslights sputtered fitfully in their sconces. Ennek counted the narrow doors as they went, forty-eight by the time they came to the entrance. Forty-eight cells, each capable of holding a person trapped like an insect in a web. The Chief used one of his heavy keys to unlock the big wooden door, they filed through, and Thelius locked it behind them. They marched up the long stairway single file and through another locked door, where a pair of guards saluted the Chief smartly.

They were back above now, and again Ennek could hear the ocean, could smell salt and fish instead of just damp rocks. He would have thought he’d be relieved, and he was, a little; but as he walked away to find his tutor, numbers tumbled through his head. Forty-eight cells. Twenty prisoners. Three hundred years.

BAVELLA WAS angry with him, but that was nothing new. Her emotions toward him generally ranged from annoyed through irritated, stopping just short of enraged. Usually it was because he hadn’t done his lessons or because his mind had wandered as she droned on and she’d had to repeat herself for the third or fourth time. “Twelve years old and still cannot properly name the principal cities along the Great Road or do his sums,” she’d hiss at him. “It’s a disgrace! Your brother could do these things before he was ten.”

“My brother has to know these things because he’ll be Chief. I don’t.”

“Even a younger son should not be ignorant.”

He’d cross his arms on his chest and set his jaw. He knew what kind of future awaited him, a life very like his uncle Sopher’s. Sopher had an official title, of course—he was the Censor—but he left the work to his underlings and spent his time sailing the bay in his bright little boat, or hunting in the headlands to the north, or playing in the Gentlemen’s Room at the gaming house.

Today, though, it wasn’t Ennek’s inattention that had brought the wrath of his tutor but rather the questions he had asked her. About traitors and punishments, mostly.

The frown line between her light brows deepened. “That is none of your concern.”

“But this morning I was Under, and—”

“You shouldn’t—” She bit back the rest of the sentence, apparently unwilling to criticize the Chief’s decision. She took a deep breath, then went on. “You were permitted to accompany your brother only because you pestered so thoroughly, and only because the Chief was in a generous mood. You should be thankful you were allowed so much.”

Ennek wasn’t thankful. In fact, he regretted the tour. He kept seeing that unmoving white flesh before him, the man’s face not looking asleep or dead but something else altogether. Kept hearing the din of the waves, feeling the little trickle of dampness as it ran down uneven stone and dripped onto the floor. And kept seeing the long corridor lined with doors, and imagining the uncomfortable possibilities behind them. Were they imprisoned in the dark, he wondered. They must be—what need did those in Stasis have for light?

He shivered, and Bavella narrowed her eyes. “We were discussing history. The line of accession for Praesidium that leads directly to the Chief. This is your own family, boy!”

“A bunch of angry-looking old men,” he muttered, ignoring her scandalized gasp. “I don’t want to know about them. I want to hear about the others, the ones who questioned them.”

“Nobody remembers them,” she answered coldly. “That is, after all, the point of Stasis. They’re locked away Under until even their names have been lost, and then they live out the rest of their days as bond-slaves, just more wretches cleaning the filth from the streets or digging in the quarries. And it’s a fate too good for them, I think. Daring to question their betters!”

“But—”

“Enough! Recite, or I shall have to report your lack of progress.” She pounded her finger against the open book.

Ennek glowered, but he began to read. He didn’t much feel like being punished today.

“IF THIS automated wagon of theirs is perfected, then Horreum will be able to convey shipments quickly without even needing the bay, and then what will become of us?” The chief of Nodosus sounded worried, but then, he always did.

Ennek’s father snorted dismissively and swallowed a mouthful of beef. “If, if this folly of theirs actually works—and I have grave doubts about that—and if it actually proves capable of hauling cargo, then they’re going to rely on the polises over the mountains to supply the coal to run the thing, and the polises between to allow their contraptions passage. Horreum has no treaties with those states, or very weak ones at best. Even if they can negotiate something, much of Horreum’s power and profits will be whittled away.”

“But—”

“And!” The Chief silenced the other man with a gesture of his fork. “And in any case, other polises would still rely on the bay for overseas trade. Where else would the great ships dock? Among the rocks to our south? Or perhaps the even bigger rocks to our north?”

“Yes, yes. But if Horreum has the most efficient way of transporting overland, they could gain a monopoly on it, and then their power might eventually rival yours.”

It was Larkin who responded to the visiting leader. “Sir, I doubt very much there’s any danger of that, especially when we have such good allies as yourself.”

The chief of Nodosus beamed at the compliment, and a quick look of satisfaction flashed over the Chief’s face. Even Ennek could tell that Larkin made a good diplomat, but still he rolled his eyes theatrically at his friend Gory, who sat across the table from him, stuffing bread into his face. Gory grinned back and then gestured with his head toward the door.

“Excuse me, sir,” Ennek said to the Chief. “May I be excused?”

The Chief nodded absently and then started pontificating about the perils of steam engines. Ennek took a last gulp of watered wine, wiped his mouth, and rose from the table. He jogged to his own chambers, thankful that, while he was old enough to have to attend these dinners now, at least he didn’t have to stay for the endless, boring discussions that always followed. In his room, he considered changing into slightly less formal clothes—his new suit was itchy and not very comfortable—but decided instead to just throw on his warmest coat. He clattered back through the hallways, sometimes nodding to guards and various functionaries as he passed, until he ascended a steep, winding stairway.

Gory was already waiting for him on the roof. His corn-silk hair was whipping around, and his handsome face was tilted in its usual smirk. Ennek could see his tan even in the moonlight; Nodosus was a day’s ride inland, where the sun shone almost all the time.

“That brother of yours has been practicing sucking up,” Gory said by way of a greeting.

“Yeah. He’s getting pretty good at it.”

“Well, dear old Dad sure ate it up.”

They walked to one edge of the roof and bent over the railing to look at the water. The foam was phosphorescent, as otherworldly as the moon. They had to raise their voices a little to be heard. “You ever swim in it?” Gory asked.

Ennek shook his head. “No. Too cold.”

Gory sneered. He was eighteen months older than Ennek and six inches taller. Someday he would be a chief too. He pointed at Rennis Island, the lights of which were just visible through the gathering fog. “I bet I could swim out there. It’s not that far.”

“It’s cold,” Ennek repeated. “And there are sharks.”

Gory flapped his hand, whether at sharks or at people who were afraid of them, Ennek wasn’t sure. “I could do it. I swim in the river all the time, even in the spring when it’s all melted snow, and that’s cold, boy. And there are things that live in the river, too, deadlier things than sharks.”

Ennek didn’t know if this was true. He’d never been beyond the walls of Praesidium, unless you counted an afternoon or two sailing in the bay or the one time Sopher had taken him to hunt deer.

He trailed Gory as the older boy stomped across the roof to the other side. Gory had a pocketful of pebbles, and he began dropping them over the edge onto the helmets of the guards below, pulling back out of sight when the guards looked up. “Here,” he said, laughing and holding out a few small stones. “You try.”

Ennek imagined the Chief’s face if he found out. “No, thanks,” he mumbled.

“Aw, c’mon.”

Ennek found himself taking some of the smooth little things in his hand, then creeping to the railing. When the next guard walked by on his rounds, Ennek let go, and two pebbles plunked loudly off the man’s head. Ennek crouched down, giggling.

“How about this?” Gory said. Now he was holding a larger chunk of stone, almost as big as his fist. It looked as if it had crumbled off the battlements.

“I’m not gonna drop that on someone’s head!”

“Why not? They’re wearing helmets. It’s not like you’re gonna kill anyone.”

But Ennek shook his head, and Gory let the stone fall to his feet with a sizable clomp. A loud silence followed, Gory’s full lips pulled up on one side, his lean hips cocked just so, one perfect eyebrow arched high.

“I went Under last month!” Ennek suddenly blurted.

Gory’s eyes widened and then immediately narrowed. “You did not.”

“I did! The Chief took Larkin to see and I was invited along.” It wasn’t quite far enough from the truth to be a lie.

Gory came very close to him, looked him up and down, and then leaned against the stone railing. He was trying for nonchalant but not quite managing, to Ennek’s great delight. “What was it like?” Gory finally asked. Nodosus had no Under. Its worst criminals were simply hung, which was rather efficient but, the Chief had said, barbaric. Not to mention dangerous—a dead traitor could too easily become a martyr. But Nodosus’s wizard was much less powerful than Praesidium’s, as was fitting because Nodosus itself was much less powerful than the great polis to the west. Nodosus’s wizard undoubtedly lacked the skill for Stasis.

Ennek looked at the way Gory’s hair hung in his face, almost covering his eyes. He wondered what his own hair would look like if he allowed it to grow so long. Not the same, of course. Ennek’s hair was thick and curly and nearly black. He imagined Gory’s must feel very soft. “It was no big deal,” he said.

“Oh?”

“Thelius showed us one of the prisoners. He was…. He looked kind of like a statue or… or a doll.” That wasn’t quite right, but it was as close as he could get. “And he was naked,” he added in a near whisper.

“Really?” Gory’s eyes shone in the cold moonlight.

“Really. He was in this sort of hammock thing. Thelius said their skin wears through if they’re just left on the ground. Not that they’d feel it, but they would when they woke up.”

“So you could do, like, anything to them, and they wouldn’t know?”

“Yeah, I guess.”

Gory chewed at his lip for a moment. “I want to see one!” he announced.

“Um, I guess your chief could ask mine.”

“No. You know they’d never let me.”

“Well, maybe someday when you’re chief, you could—”

“That’s a million years away, Ennek! I want to see now. Tonight.”

Ennek swallowed. “No way.”

Gory stood in front of him, stooping slightly so they were eye to eye. “Come on. Just a peek. We can go after everyone’s asleep and nobody will ever know.”

“But what if they found out?”

“They won’t,” Gory huffed. “Don’t be a baby. I’ve snuck into tougher places than this plenty of times.”

Ennek was skeptical about that. Besides, even if it was true, Gory had done his sneaking back home, where he was heir and the Chief had no authority. Ennek was going to say no again, was going to just turn away and go back inside, actually, when Gory stuck out his arm and clutched Ennek’s shoulder with his tanned, man-sized hand. “Come on,” Gory purred.

And to his own dismay, Ennek heard himself agreeing to meet his friend outside the dining hall in three hours.

“THAT’S YOUR spy outfit?” Gory scoffed.

Ennek looked down at himself. He was wearing a pajama top tucked into a pair of old trousers that were now a little short on him. He’d pulled on a sweater too, a lumpy gray one his mother had knitted for Larkin years ago, and a pair of old boots. “What difference does it make if nobody’s going to see us anyway?” he countered.

“Well, I have to see you.” Gory had on a pair of sharply creased wool pants, a dark red shirt of silky cotton, and shiny black shoes. He was going to be cold if they actually made it Under, but Ennek didn’t tell him so.

Ennek shrugged, his eyes downcast.

“Did you at least get the keys?”

Ennek looked up and grinned, then pulled a heavy iron ring from his pocket. It was Larkin’s, the set of keys he’d been given on his eighteenth birthday. Ennek had made enough secret forays into his brother’s room to know where they’d be hidden, and also to know that Larkin would be sound asleep after a heavy meal and several glasses of wine. Ennek wasn’t absolutely positive that one of the bits of metal would work on the door to Under, but he certainly wasn’t going to try to steal the Chief’s keys, or the wizard’s for that matter.

He led Gory through the empty halls of the keep. It was kind of a creepy place this late at night, when nobody scurried by with arms full of papers. There were a few guards posted here and there, of course, and a bond-slave or two down on his knees, scrubbing at the floors, but they were easy enough to avoid.

The door that led Under was well out of the way, tucked at the end of a long corridor that held mostly storerooms full of mops and towels and old furniture. It would have been completely unremarkable if it weren’t for the single guard leaning against the wall, nodding sleepily.

“How are we going to get by him?” Ennek whispered after he peeked around the corner.

“Simple.” Gory held out his hand. There were two candies there, red and sticky-looking. “Sleeping potion. My dad takes one every night. I just nicked a couple.”

“But how are you going to get the guard to take them? And when he wakes up, won’t he know he’s been drugged?”

“You’ll see, and yeah, he will, but he’s not gonna tell anyone, because then he’d get in trouble for not doing his job. Right?”

Ennek nodded doubtfully, then caught his breath as Gory marched confidently around the corner and down the hall. The guard jerked awake and stared at the approaching youth. “Hi,” said Gory.

The guard said nothing, just watched until Gory was standing a few feet away.

“Do you know who I am?”

The guard shook his head. He wasn’t much older than Gory, really, maybe Larkin’s age. His helmet looked uncomfortable where the strap dug into his skin, and he had dark circles under his eyes.

“Name’s Gory. I’m the heir of Nodosus.”

The guard straightened his shoulders until he was almost standing at attention. “Yes, sir,” he said, so quietly Ennek could barely hear.

“Have you ever been to Nodosus?”

“No, sir. I’ve never left Praesidium, sir.”

“That’s too bad. Maybe someday you can manage a visit. We have real summers, you know, with the sun blazing hot and the grass all golden, and tomatoes sweet as candy when you eat them right off of the vine.”

“Yes, sir.”

“We have traditions too. Like giving small gifts to those who work for us. Here.” He held out his palm.

The guard looked down at it. “Thank you, sir, but I really couldn’t. We’re not allowed, and—”

“Aw, it’s just a little candy. No big deal. You wouldn’t want to hurt my feelings, would you?”

Ennek was beginning to feel sorry for the man. He was about to step around the corner and end the whole thing when the guard said, “No, sir, of course not.”

“C’mon, then. They’re good.”

As Ennek peeked around the wall, he saw the guard hesitate, then gingerly pick the candies up and pop them into his mouth. “Thank you, sir,” he said with his mouth full.

“Sure thing. You have a good night now.” Gory walked back toward Ennek, who ducked out of sight.

They stood there awhile, fidgeting restlessly, until they heard a loud rustle. When Ennek chanced another look, the guard was sitting, his legs straight out in front of him and his back up against the wall. As Ennek watched, the guard slowly, slowly slumped to the side.

“Got him.” Gory grinned triumphantly and marched down the hall with Ennek at his heels. In front of the door, Gory stopped to prod the guard with his shoe. The man’s mouth hung open and a thin line of drool was running down his cheek. He snored lightly.

Ennek produced the keys again. After a few minutes of fumbling, he found one that fit the lock, which turned a little stiffly. It seemed very loud, as did the door when he swung it open. There was a light switch just inside, and when Ennek pushed the button, a row of small gas lamps hissed to life, illuminating the stairway. He locked the door behind them, noting with a thrill of satisfaction Gory’s unnaturally pale face, and led the way down.

When they were finally in the long, dank corridor, Gory let out a low whistle. “Is there somebody behind every door?”

“No. At least, not anymore. Thelius said there are only about twenty left.”

“Well, let’s see one!”

Ennek wasn’t sure which cell he’d been in before, but he didn’t suppose it mattered. He stepped—much more confidently than he felt—to the nearest door and unlocked it. Wincing slightly, he swung the door open.

There was nobody in the cell. Both boys let out sighs, maybe of mixed relief and disappointment. One of the hammock things was there, but it was empty, and there was nothing else in the room except one tiny light affixed to the bumpy walls.

Gory walked inside and, with slight hesitation, touched the ropes. “Is this what they lie in?” he asked. His voice was quiet and a little hoarse, as if he needed to clear his throat.

“Yeah.”

“It’s soft. The ropes, I mean, they’re soft, like silk.”

“I suppose that protects their skin.”

“Yeah, I guess so.” He gave the webbing an experimental tug. “Strong. Okay, let’s try another.”

The next room was even emptier, without any ropes inside, and Gory clucked. “I’m beginning to think there’s nobody here at all.”

But the next room was occupied.

It might have been the same cell he’d been in before. Certainly the prisoner looked similar, but then, maybe they all looked like that after a while—skeletal, colorless, ageless. He hung suspended, with his eyes closed in such a way that the lids seemed almost sealed. His head was completely hairless, as was the rest of him. Ennek hadn’t noted that the last time. He wondered if the prisoners were shaved for some reason, or if it was some side effect of Stasis. It made him look less human, sexless almost, despite the penis and scrotum clearly visible between his legs.

Ennek and Gory stood on either side of the prisoner, looking down at him, for a long time. Then Gory raised his arm and, very hesitantly, touched just one fingertip to the man’s bicep before quickly snatching his hand away. The man didn’t respond, of course. So Gory moved forward a bit, and this time he laid his palm flat against the unmoving chest.

Not to be outdone, Ennek rested his own hand on the man’s shoulder.

“He feels like a corpse,” Gory said.

“No, he doesn’t.”

Gory looked up sharply, but Ennek didn’t elaborate. Two years ago he’d been on his way to the stables when he heard his mother scream. He’d dashed back to the keep and had discovered a dozen people—guards and passersby—gathered around her body, broken on the hard cobblestones beneath her window. Nobody else seemed certain what to do, so he was the first to touch her, to gather her into his arms and brush the blood-soaked hair from her face. Even in his horror and grief, he’d known she was dead, the form he was cradling nothing but an empty shell. The prisoner didn’t feel like a shell. His shoulder was sharp bones and cold slick skin, but somehow Ennek could sense the spark of life still inside.

After several minutes, Gory seemed to work up more courage and allowed himself to explore the prisoner’s body. Ennek watched uncomfortably as his friend rubbed the man’s bald head and parted his bloodless lips with his fingers. Then Gory slapped the man’s chest quite hard and looked with interest as no redness resulted. Ennek turned his head away. “Don’t!” he said urgently.

“Why not? He doesn’t care.”

“It’s… disrespectful.”

“Disrespectful? This guy probably plotted to kill your father, or maybe your grandfather. He doesn’t deserve respect.”

Ennek took his hand off the man’s shoulder, shoved it into his pocket, and shifted from foot to foot. “It’s… it’s wrong.”

“I’m just curious, that’s all.”

Ennek turned his back and stood facing the open door, staring at the identical door across the way, pretending his belly wasn’t lurching uncomfortably.

After several minutes, Gory huffed out a heavy breath and stomped over to where Ennek still had his back to the cell.

“You ready, then?” Ennek said gruffly. The thought of his own bed, warm and safe and familiar, had never been so welcome.

“Do you think there are any… female prisoners? We could just take a peek.”

Ennek gritted his teeth and growled, “I don’t know.”

“Let’s find out.” Gory pushed past Ennek. Gory didn’t have the keys, though, and wouldn’t be able to open any more cells. Ennek could just leave right now, should leave right now, and Gory would have to comply or face being locked down here by himself, in the dark. Ennek was pretty certain Gory wasn’t prepared to face that.

Gory waited impatiently at the next door down the corridor. “C’mon, Ennek. We don’t have all night.”

Ennek looked back and forth between the other boy and the door leading to the stairs. Gory was shivering with cold—just as Ennek had predicted—but his face was flushed with excitement and his blue eyes were sparkling brilliantly in the gaslight. “Just one more,” Ennek sighed, and Gory let out a small whoop of triumph.

Something made Ennek pause before he unlocked the door, but Gory pounded his back. “Hurry!” he said, his breath hot against Ennek’s neck.

Ennek unlocked the door to find another man. Gory made a disappointed sound and grabbed Ennek’s arm, as if he was going to drag him away, probably to try another cell. But Ennek was drawn forward. There was something different about this prisoner, despite the fact that he looked like the others suspended in white ropes, pale, hairless, and skinny.

Ennek reached for him, intending, perhaps, to touch his shoulder. But just before their skin made contact, the man’s eyelids opened.

Behind him, Gory screamed and scrambled away, but Ennek was too petrified to move. The man’s eyes were the color of the sea, all greens and grays, and although the pupils seemed unnaturally large, Ennek thought the man’s gaze was focused on him. His eyes were pools of anguish. The prisoner twitched then, just a tiny movement of his upper body, and made a small sound somewhere between a moan and whimper.

“Are you awake?” Ennek rasped.

The man twitched again and gasped. And then his eyelids fell closed and he was as still as death.

“Are you awake?” Ennek repeated, but there was no response. He steeled himself and, with all the courage he could muster, touched the man’s cold cheek. Nothing happened.

“Ennek! Let’s get the hell out of here!” Gory sounded like he might be about to cry, and he tugged again on Ennek’s arm, more frantically this time.

Ennek brushed the man’s cheek again, softly. Then he turned and let Gory haul him away.

Chapter One

THE MAN named Wick was cheating. He wasn’t all that good at it, but Ennek supposed Wick was too drunk to concentrate. Ennek was not drunk. Not yet anyway. He preferred to wait until he was in his own chambers for that, ever since the time he’d had almost a full bottle of whiskey and had serenaded the innkeeper’s son. Someone had called the guard, the guard had recognized him and notified the Chief, and the Chief had had him dragged back to the keep and kept under lock and key for a month. He could still picture the startling color of the Chief’s face the next day, almost purple. “You will not dishonor me or this family or the office I hold. Do not think that blood ties will protect you from punishment.”

Ennek had had a flash of memory then. A cold stone room. A web. The sea. He didn’t know what it meant, but it made him shudder.

Taking a deep breath as if to calm himself, the Chief had come so close that he was looming over the chair in which Ennek sat. “You haven’t traveled beyond those sleepy little inland cow towns. You don’t know what the other great port cities of the world are like. They are pits of vice and degradation, filthy cesspools of corruption and depravity. What makes this polis the greatest in the world isn’t our propitious location but the rules with which we live, the laws that ensure order and morality.”

Ennek had nodded to show he was listening. He fought the urge to look down at his lap like a chastened child and instead stared directly ahead at the Chief’s orderly desk. It loomed as vast as a playing field.

“I am the hand of the law. The last place I will tolerate disgrace is in my own keep, in my own home. Is this understood?”

“Yes, sir.”

“This will be the last time we have this discussion.”

So now Ennek spent his evenings at the inns or the gaming house and drank only sparingly until the night was waning and the proprietors were eyeing him impatiently. Then he’d stalk home through fog-shrouded streets and climb the hill, nod to the guards at the entrance of the keep, and find his way to his chambers. He’d shuck his coat and kick off his boots and, if the fire in his room burned hot enough, discard the rest of his clothing as well, and he’d sit on his leather chair and drink good red wine until his mind was as murky as the streets. Then he’d crawl into bed and pass out. The Chief undoubtedly knew about this but didn’t seem to care, as long as Ennek remained sober and controlled in public.

Wick glanced slyly at him from under lowered lashes and slid a card out of his sleeve, using it to replace another that he quickly palmed and hid away. Ennek pretended not to see, instead bobbing his head absently at the music that trickled in from the common room.

The two other men at the table knew what was going on. They’d played with Ennek many times before and, unlike Wick, were well aware of who he was. But this was Wick’s first time in the Gentlemen’s Room. He owned a small ship, he said, and had recently sold a cargo of exotic cloth for a tidy profit, enough to allow him to move up in the world. These two men didn’t bother to tip the newcomer off. Instead they played conservatively, folding early, waiting and watching to see what the Chief’s younger son would do.

Wick splayed his cards face up on the table and smiled. “Three kings,” he said.

Ennek put his own cards down. He had nothing but a pair of sevens. He smiled back as Wick scooped up the pile of chips in the center. “You’re having quite a run of luck,” he said easily.

“Well, beginner’s luck maybe, seeing as how I’m new here.”

“Maybe,” Ennek agreed.

One of the other men dealt the next hand, and this time Ennek won with a full house. Wick had folded early, though, and lost only a little.

The next time around, Wick again replaced a card with one from his sleeve. He was fairly good at it, actually, might even have pulled it off if he hadn’t overindulged from the bar. When he put his cards down this time, he grinned triumphantly over a straight, queen high. Ennek had three aces. He waited until Wick had again scooped up his winnings and then chuckled. “You’re cleaning me out, friend. I’m going to have to call it a night.”

“Maybe you’ll win next time,” Wick said. His teeth were crooked and yellow, like a rat’s. His blue suit, though, was very fine. It wouldn’t fit Ennek—Wick was only a little taller, but much scrawnier, apart from the bulge of his belly—but it was worth a small fortune, probably. The buttons were gleaming silver, the cloth rich and well dyed.

“I’ll tell you what,” Ennek said. “One more hand. But instead of money, let’s wager something else.”

Wick’s expression sharpened with interest. “What did you have in mind?”

“Your suit. I’ll wager your suit against this.” He slid a heavy gold ring off his finger and set it on the table. It had been his eighteenth birthday gift—a fancy bauble in place of the keys of office—and it was inset with a large red stone imported from overseas. It was worth far more than the clothing.

Wick’s eyes grew very wide, and he stared at the ring as if mesmerized. The other two men sat back comfortably in their seats. Their faces were neutral, but they knew the denouement of the evening’s little drama was close at hand.

“All right,” Wick said. His voice shook a little.

The man to Ennek’s right began to shuffle the cards. Ennek hummed quietly. Just as the man cut the deck, a split second before he began to deal, Ennek said, “Did you hear what the Chief did last night?”

“No, what?” said the dealer, not quite suppressing a smile.

“He found four men guilty of cheating—three at cards, one at dice. He sentenced them all to ten years as bond-slaves.”

Wick swallowed audibly.

The man to Ennek’s left said, “Well, the Chief has little patience for swindlers. I’ve heard he’s told the guard to keep an eye out for them. Is that true, Ennek?”

Ennek watched as the dealer handed a card to Wick, who took it distractedly. He’d grown pale.

Ennek smiled and shrugged. “I don’t know. I don’t keep very close tabs on what my father’s doing.”

All three men looked worried as Wick had a sudden choking fit. “Can I get you some water?” Ennek asked politely.

“No… um… I’m fine. Just fine.”

“Well, then, let’s play this hand, shall we? It’s getting late.”

Ennek whistled as he walked home. It was earlier than usual for him, and a few people still strolled the streets. At the bottom of Keep Hill, he passed a freedman who was pushing a small wagon, probably laden with whatever junk he’d managed to scavenge for sale. Ennek handed the bundle of blue clothing over to the astonished man. “Here you go.” He smiled. “Doesn’t fit me well, I’m afraid. But it looks about your size.”

As the man gaped, Ennek continued on his way, his whistling interrupted by guffaws as he pictured Wick scuttling home wearing only his underclothes beneath his coat.

“YOU NEED a job,” Larkin said.

Ennek put his feet on the low table of carved cherrywood with inlaid mother-of-pearl. Ugly as hell, he thought, but very expensive. Larkin scowled at him.

“I have a job.”

Larkin leaned back and crossed his arms. “Oh? And what exactly is that, dear brother?”

“I read over treaties now and then. And when I’m not, I am the official Degenerate and Dissipated Younger Son.”

“You read over treaties maybe twice a year. And the rest—that’s going to get you in trouble.”

“I do it quietly, now. Mostly.”

Larkin sighed. “Why can’t you just find some pretty girl and get married and—”

“That’s my new job? Breeding? Carrying on the family line? I thought that was your purview, Lark.” The heir’s wife had just delivered their third child.

“That’s not what I meant. You’re not a kid anymore, En. You need to settle down. You don’t have to adore the girl, just—”

Ennek looked his brother in the eyes. “I can’t. Wouldn’t be fair to her, whoever she might be, would it?”

Larkin opened his mouth, then closed it. This was as near as they’d ever come to saying the truth, the real reason Ennek hadn’t settled down and never would. They’d go no further, certainly not here in the keep, certainly not when Larkin himself would sometime soon be charged with enforcing the Morality Code.

Larkin shook his head sadly. “Fine. But I do have a job for you, a real one. Something that could keep you busy if you let it.”

“What?”

“Portmaster.”

Ennek thought he’d misheard. “Say again?”

“Portmaster,” Larkin repeated patiently.

“Busy, huh? Keeping track of every ship in and out, inventorying and taxing the cargos, overseeing the stevedores and longshoremen, maintaining the docks… sounds like a little more than busy to me.”

Larkin waved his hand. “You can have assistants do most of that on a day-to-day basis. You just check in on them as often as you want to. Watch out for corruption, make sure everything’s running smoothly.”