Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dreamspinner Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

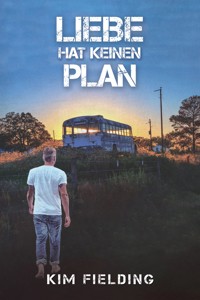

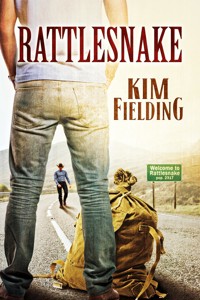

A drifter since his teens, Jimmy Dorsett has no home and no hope. What he does have is a duffel bag, a lot of stories, and a junker car. Then one cold desert night he picks up a hitchhiker and ends up with something more: a letter from a dying man to the son he hasn't seen in years. On a quest to deliver the letter, Jimmy travels to Rattlesnake, a small town nestled in the foothills of the California Sierras. The centerpiece of the town is the Rattlesnake Inn, where the bartender is handsome former cowboy Shane Little. Sparks fly, and when Jimmy's car gives up the ghost, Shane gets him a job as handyman at the inn. Both within the community of Rattlesnake and in Shane's arms, Jimmy finds an unaccustomed peace. But it can't be a lasting thing. The open road continues to call, and surely Shane—a strong, proud man with a painful past and a difficult present—deserves better than a lying vagabond who can't stay put for long.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 409

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Readers love

KIMFIELDING

Astounding!

“I absolutely love it when Kim Fielding decides to go on yet another genre freestyling endeavour. I get chills when she does this.”

—On Top Down Under

“I loved this book! It was quirky and the characters were interesting and fun.

—Reviews by Jessewave

“…if you are looking for another sweet story from the very talented Kim Fielding, this could be just what you need.”

—My Fiction Nook

Grown-up

“I adore Kim Fielding. Her books are always awesome. Sometimes thought provoking. Terribly sweet and always heart-warming… I highly recommend this book and this author.”

—The Kimi-chan Experience

The Pillar

“For all that this was only novella length, it packed quite a punch. The love, the hurt, the joy, the regret—it was all felt and felt quite deeply by both them and me.”

By KIM FIELDING

Alaska

Animal Magnetism (Dreamspinner Anthology)

Astounding!

The Border

Brute

Don’t Try This at Home (Dreamspinner Anthology)

A Great Miracle Happened There

Grown-up

Housekeeping

Men of Steel (Dreamspinner Anthology)

Motel. Pool.

Night Shift

Pilgrimage

The Pillar

Phoenix

Rattlesnake

Saint Martin’s Day

Snow on the Roof (Dreamspinner Anthology)

Speechless • The Gig

Steamed Up (Dreamspinner Anthology)

The Tin Box

Venetian Masks

Violet’s Present

BONES

Good Bones

Buried Bones

The Gig

Bone Dry

GOTHIKA

Stitch (Multiple Author Anthology)

Bones (Multiple Author Anthology)

Claw (Multiple Author Anthology)

Published by DREAMSPINNER PRESS

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com

Published by

DREAMSPINNER PRESS

5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886 USA

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of author imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Rattlesnake

© 2015 Kim Fielding.

Cover Art

© 2015 L.C. Chase.

http://www.lcchase.com

Cover content is for illustrative purposes only and any person depicted on the cover is a model.

All rights reserved. This book is licensed to the original purchaser only. Duplication or distribution via any means is illegal and a violation of international copyright law, subject to criminal prosecution and upon conviction, fines, and/or imprisonment. Any eBook format cannot be legally loaned or given to others. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact Dreamspinner Press, 5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886, USA, or http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/.

ISBN: 978-1-63476-476-6

Digital ISBN: 978-1-63476-477-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015906570

First Edition August 2015

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHAPTER ONE

ITBEGAN with a dead man.

No, that’s not right. It began before that for Jimmy Dorsett, who was very much alive and alone in a wide, empty desert, listening to his Ford clatter and groan and wondering how much farther it would take him. He would rather have listened to the radio, but it was already busted when he bought the car. So was the AC, which was why he was driving at night. One of the reasons, anyway.

He knew if he slowed down, the car might last a few more miles, but he kept his foot heavy on the pedal. He told himself it was because he’d been guzzling coffee to stay awake and now he had to piss. But the fact was, he always drove fast even when he had nowhere to be.

He could have pulled over and watered a Joshua tree but decided to hold it awhile longer. He needed more coffee too, and the gas gauge hovered not far above the red E.

He saw the lights from miles away, and as he drew closer, he realized he was nearing a tiny town. Not much of a place. A few houses, small and close to the highway, but somebody lived in them, and those somebodies had more than he did. A couple of buildings contained businesses of some kind, but Jimmy couldn’t tell in the darkness whether they were closed for the night or closed forever. Two enormous gas stations sat across from one another, each with a convenience store and plenty of room for semis to pull in and turn around. The bright lighting was cold and hard and did nothing to warm the desert night.

Jimmy turned into the station on his right.

He went inside to use the can before he did anything else. The clerk was a big guy with a scruffy beard, and he eyed Jimmy carefully. Jimmy imagined the guy’s hands rested close to a gun, just in case.

The bathroom was dirty, but he’d seen worse. Much worse. At least the sink worked, so he washed his hands and splashed cold water on his face. There was no mirror, which was just as well.

When he was done, he picked up a bag of chips and a king-size Snickers bar and filled their largest paper cup with coffee. He took his purchases to the counter. “And thirty bucks of regular,” he said. Gas prices had gone down lately, allowing him to get a lot farther than he used to, but still his little stash of bills was pitifully thin.

The cashier rang him up, took the money, and handed him change and a receipt. Didn’t say anything, not even Thanks or Have a nice night. So Jimmy smiled at him and said, “Thank you. Hope you have a good day.”

The man didn’t respond.

Jimmy gassed up the Ford, listening to the fuel line hum, thinking about nothing much. He could do that—shut off his mind and wait for whatever came next.

Then he was back in his car with the motor running and bad coffee burning his tongue. He had a decision to make. The town was at a crossroads, so assuming he didn’t want to retrace his journey, he could travel in any one of three directions. He drove to the edge of the parking lot and idled for a moment. North, west, east. None of them looked any more or less promising than the others. The pavement all looked the same.

And then he noticed the old man.

He stood near the gas station across the street, his back against a thick metal light pole, a backpack lying at his feet. He was bearded, grizzled, and wore a stocking cap pulled low on his head and a jean jacket faded almost to white. The jacket wasn’t heavy enough for a desert night, and the man shivered. He wasn’t looking at Jimmy’s car or the two semis idling nearby. He looked like a man who’d given up on waiting a long time ago.

Jimmy had been that man more than once over the years. No bed, no money, no hope. Hell, once the Ford finally croaked and he ran though the last few dollars in his wallet, Jimmy would be that man again.

But at the moment he had a car that ran, and he had a little food and a little cash. So he drove across the empty highway and stopped in front of the old man. He opened his door slightly—the window was stuck—and asked, “Need a ride?”

The guy didn’t even pause to assess him. He just picked up his pack, which looked heavy, and threw it in the backseat before sitting in the front. He and Jimmy closed their doors.

“Where you heading?” Jimmy asked.

“Rattlesnake.”

Jimmy shook his head. “Never heard of it.”

“’S up north, on Highway 49. Gold rush country.” He had a voice like a truck driving through deep gravel, bumpy and broken. “You headin’ that way?”

“Sure. If the car makes it that far.”

Looked like Jimmy had a destination after all.

THEMAN’Sname was Tom, and he reeked of cigarettes, booze, and the type of old dirt that’s been building up a long time. Of course, Jimmy had been sleeping in the Ford lately, and he probably didn’t smell his best either. They put up with each other’s stink without complaint.

Tom could have been any age from fifty to eighty. His eyes were watery and his hands shook. He coughed often, a thick sound, and he turned down Jimmy’s offer of chips and candy. “Ain’t hungry.”

“When did you eat last?”

“Dunno. But I ain’t hungry.”

Well, you couldn’t force a man to eat. But Jimmy saved some of the Snickers bar, just in case.

Maybe Tom would have slept. But the road was long and empty, and Jimmy hadn’t had a conversation with anyone in ages. “Were you waiting for a ride for a long time?” he asked.

Tom grunted. “Since sunset. Trucker took me there all the way from Flagstaff, but he was turnin’ down to Santa Clarita. Nobody stopped for me since then.” For the first time, he took a good look at Jimmy. “Why’d you stop?”

“You looked cold.”

“Where you goin’? I know it ain’t Rattlesnake.”

Jimmy shrugged. “Didn’t have anywhere specific in mind.”

“You runnin’ from something?”

“Nope. Just… driving. How about you? What’s in Rattlesnake?”

Tom paused a long time before answering. “Used to live there. Long time ago. Thought maybe—” He stopped to hack up half a lung, and when the coughing ended, he didn’t finish his thought. He turned his head away from Jimmy to stare out his window at nothing while Jimmy stared straight ahead at not much more than nothing.

The silence grew too loud. “Have you ever been to Minden, Nebraska?” Jimmy didn’t wait to see if Tom would answer. “It’s in the middle of nowhere, except it’s not too far off I-80. I stayed awhile there, a few years back. There’s a tourist attraction—Harold Warp’s Pioneer Village. It’s sort of a collection of collections. Like everyone in Nebraska emptied out their attics, garages, and barns and dumped the contents there in Minden.” He’d spent a summer working the snack bar there, flipping burgers and dumping fries into hot grease. It had paid just enough for him to rent a room from an old couple who lived nearby. Hadn’t been a bad gig.

“Never been,” Tom said.

“Well, it’s worth a visit if you’re in the neighborhood.” He remembered the oppressive heat of a Nebraska summer, the way the plains seemed as endless as the sky, and the fireflies that danced in the evenings.

He shifted slightly in his seat. The springs were shot. “They have all these cars. Starting from horse-and-buggy days, actually. Then they have a steam car, some Fords even older than this piece of crap… all the way through the years. But it’s not the biggest collection of cars I’ve seen. I worked for a few weeks once on a farm in Missouri, helping build new fences. My boss there, he had a couple of huge barns completely full of cars. Hundreds of ’em. He was addicted to car auctions, I guess. None of them ran. They were dusty, full of spiders and bugs and mice. But he kept on buying more.”

His passenger didn’t reply. Didn’t even cough. Jimmy swallowed some of his coffee, which had cooled to bitter sludge. “One time I was riding a Greyhound bus to…. Shit. Don’t remember where to. I remember it was raining, though, and you couldn’t see through the windows ’cause they were all fogged up. There was a lady sitting a couple rows up from me. She wasn’t hardly more than a girl, really. She was on the bus already when I boarded, and she looked real scared when I walked by, like maybe I was gonna hurt her or something.” Jimmy got that look often. He wasn’t huge, but he was big enough when he carried some weight, and he figured there was a toughness to his face. Mostly he didn’t mind if people were a little scared of him—it meant they were less likely to try to fuck with him. But sometimes it made him sad and lonely, and that day on the bus had been one of those times.

“So there we were, bumping along in that bus, on our way to somewhere. There weren’t many passengers. And the girl, she made this funny sound. Sort of a muffled scream? I got out of my seat and asked her if she was all right, and she looked up at me with the biggest eyes I ever saw. ‘I’m having a baby,’ she said. And she sure as hell was. Driver pulled over and called for paramedics, but that baby was in a hurry. He was born right there on the Greyhound, with the driver and me and a soldier helping out. I got to be one of the first human beings that little boy ever saw. I wonder how he’s turned out. He’d be near twenty now. Almost as old as I was then.

“That baby looked up at everyone with astonishment clear in his eyes, and he squalled loud enough to wake the dead. It’s supposed to be a good thing when a newborn cries so strongly, I know that. But still, I always wondered if that kid hadn’t been damned disappointed with the life he’d been born into.”

After ten or fifteen quiet minutes, Tom cleared his throat. “You got people somewhere? Family?”

That was a simple question with a complicated answer. Jimmy said, “Not really.”

“Me either. Not no more. Used to, though. How old are you?”

Jimmy had to calculate a bit in his head to answer precisely. “I turned forty-three last month.” He hadn’t celebrated it—nobody to celebrate with. Fuck, he couldn’t remember the last time he’d known anyone well enough for them to wish him a happy birthday.

“Then you still got time.”

“Time for what?”

Tom coughed some more before answering. “Listen to me, Jimmy. Someday you’re gonna be an old bastard like me, and you’re gonna regret shit, and you ain’t gonna be able to do nothin’ about it. Don’t wait. You got stuff in your life needs fixin’, you gotta fix it now, while you can.”

Trying to ignore the sharpness in his chest, Jimmy shook his head. “I’m fine. I’ve just got itchy feet is all. I can’t stay anywhere very long before I have the urge to move on. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

Tom snorted. “Ain’t nothin’ wrong with it long as you’re happy. Are you happy?”

Jimmy didn’t reply.

A few miles later, Tom removed a paper from his pocket. It crackled a bit when he handled it. Out of the corner of his eye, Jimmy saw him unfold it and stare at it awhile even though the car was too dark for him to read. Then Tom folded it again and tucked it away.

“I had a son,” Tom said very quietly. “Back in Rattlesnake. I loved that boy. But I guess I loved the bottle more. Left him and his mama when he was just little, and I ain’t seen him since.”

If Jimmy hadn’t been driving, he’d have closed his eyes tight. Instead he narrowed them and kept his gaze forward, where the road had begun to rise a little toward Tehachapi Pass. “How old is he now?” he asked, tight-throated.

“Dunno.” Tom coughed a minute. “Grown.”

“So why are you going to Rattlesnake now?”

“Got sick. I think it was all that fucking regret sitting in my belly, growing like cancer. I wrote him a letter. I was gonna mail it, but I don’t know his address. Don’t know if he’s even there anymore. Maybe he moved on years ago. But I couldn’t just throw the damn letter away. Tried to, but couldn’t. So I decided to try to deliver it myself. If he’s still there.”

Wishes were like poison, Jimmy thought. When you made them, they were all bright and shiny, sweet as candy. But they lingered and languished and didn’t come true, and so they curdled and went bad. Became toxic. That’s why he never made them to begin with.

“I hope you find him,” Jimmy said.

The response came as a sigh. “Yeah. It’d sure be nice to see him, even if he hates my guts. I don’t care if he yells and calls me names. I just wanna see him.” And he moved his seat back a little—Jimmy was surprised it could still recline—and closed his eyes.

Jimmy took another swig of coffee.

THEFORD grew louder as it climbed the mountain, until it was grumbling and clanking alarmingly. Jimmy eased up on the gas and hoped the car would be happier once he began to descend. But it wasn’t. If anything, its complaints grew louder as he coasted down into farmland, rolled through the sleeping city of Bakersfield, and headed north on Highway 99.

Normally he wouldn’t have worried about the car—if it died, it died. It had happened to him with other cars. He could hitch a ride, or he could stay put long enough to earn money for a bus ride or another junker car. He wouldn’t even have been bothered by the very early hour, because the temperature here was tolerable and big rigs plentiful. But for once he actually had a destination in mind. And he had a passenger. He truly wanted to get Tom to Rattlesnake.

As he drove on, the sky to his right began to lighten although the sun hadn’t yet appeared over the Sierras. The car made noises like a bad concert, he decided. One with too much percussion and with guitarists who couldn’t agree on which song they were playing. He made up lyrics in his head to keep himself awake. This is it, for my piece of shit, car that’s gonna up and quit. It’s not fine, to lose what’s mine, here on fuckin’ Ninety-nine. Yeah, well, he’d never claimed to be a musician.

Despite the din from the engine compartment and inside his head, Jimmy’s eyelids grew heavy. They still had another two or three hours before they reached Rattlesnake. The car might make it, but it didn’t look like he would. At least not without a nap. He was relieved when he came upon a rest area at the southern outskirts of Fresno, and he took the exit gratefully. “Just need a little shut-eye. Thirty minutes.”

Tom didn’t answer.

The parking lot was empty except for a handful of trucks clustered at one end and a beat-up old van near the bathrooms. The big overhead lights had switched off, but the morning light was still tentative and dim. Jimmy piloted the car to a spot far from the other vehicles and cut the engine, which stopped with a final clatter and a tired sigh.

Before he got too comfortable, his bladder reminded him how much coffee he’d drunk. “Fuck. Be right back,” he said to Tom, who still snoozed away. Jimmy pulled the keys from the ignition and turned to give Tom a good poke. “I’ll be right back,” he repeated more loudly.

And that’s when Jimmy realized Tom wasn’t sleeping.

“Fuck!” he yelled as he scrambled for his door handle. Once he got the door open, he nearly fell out of the car. He stood there breathing hard, staring at his passenger.

Tom didn’t look much worse than he had in life. His eyes were closed, his mouth hung slightly open, and his skin had taken on a waxy pallor. But there was no sign of distress on his face, and if he’d made any sound when he died, it had been too quiet to hear over the racket of the car.

Although Jimmy had witnessed only one person entering the world, he’d seen several people shortly after they’d left. Overdoses. Accidents. Once he’d seen a bunch of cops clustered around a lonely corpse at the side of a highway. Someone had covered the body with a blanket, but its bare feet stuck out. And for a few sticky summer months in a southern town he couldn’t now name, he’d worked as a cemetery groundskeeper—mowing the lawns, trimming the trees, getting rid of faded flowers. He hadn’t actually seen any dead people then, just their caskets and their freshly filled graves. But death wasn’t new to him by any means. It just didn’t usually ride shotgun.

He calmed rather quickly, then considered what to do next. His first thought was to keep driving all the way to Rattlesnake, find Tom’s son, and hand over the body. Except Jimmy didn’t like the idea of driving with a dead man, and it would be a hard thing to explain to the cops if he got pulled over. Or if his car followed Tom’s lead and died too.

He could dump the body somewhere and take off. But that was sneaky. And poor Tom didn’t deserve to be treated like a sack of litter. Besides, in today’s Big Brother world, there were apt to be surveillance cameras somewhere, and then once again the problem of explaining himself would arise.

His best option, he finally decided, was to get the cops involved right away. Yes, he’d still have to explain—no getting around that—but he wouldn’t look nearly so suspicious.

Fuck. Cops made him… itchy.

Jimmy decided that his bladder was a bigger emergency than Tom, seeing as Tom was already dead. He hurried across the lot to the dank bathroom, pissed like a racehorse, and washed his hands. When he emerged from the smelly little building, he looked for a public telephone. He found one all right, but it was busted. The handset was cracked into pieces, the bottom half still hanging from the cord.

He considered trying the van but vetoed that idea and loped to the big rigs instead. He pounded on the driver’s door of the first one he came to. Crete Carrier, said the neatly painted lettering on the cab. Lincoln, Nebraska.

He had to pound a second time before the driver appeared at the window to glare at him. “Whaddya want?” the guy yelled. His wispy gray hair stuck almost straight up in a case of bedhead that might have been funny under other circumstances.

“I need you to call the cops!” Jimmy shouted back.

“Why?”

“I got a dead guy in my car!”

Well, that got the driver’s attention. He blinked at Jimmy in astonishment before disappearing. He must have been calling or radioing his buddies, because within moments all the trucks disgorged men who looked as if they’d woken suddenly from a deep sleep.

“Show me,” said the Crete Carrier guy.

They silently followed Jimmy across the lot, looking like a baseball-cap-wearing funeral procession. When they reached Jimmy’s Ford—with the driver’s door still wide open—they clustered around and gaped.

“Yeah, he’s dead all right,” concluded one of the truckers, a man with a big belly and a bushy beard.

“Who is he?” asked another. “Your daddy?”

Jimmy shook his head. “A hitchhiker. I picked him up in the desert. I thought he was sleeping.”

“Well, that’s fucked up.”

Jimmy had to agree with that assessment.

Eventually someone got around to calling the police, and two cars arrived ten minutes later, sirens wailing. An ambulance trailed behind. The truckers backed away a little when the cops came near, but Jimmy stood his ground. Tom had apparently become his problem.

While most of the emergency personnel concentrated on Tom, one cop drew Jimmy aside. He was Officer R. Ramirez, according to his name tag, and if Jimmy had been into men in uniform, this man would have been his wet dream. He was tall and buff, with short dark hair, big brown eyes that crinkled at the corners, and a square chin. He looked Jimmy up and down carefully, and if he was displeased by what he saw, at least he managed to keep a neutral expression.

“Can I see your driver’s license please, sir?” Ramirez asked.

Jimmy pulled the license from his wallet. It had been issued in South Carolina eight years earlier, but it was still valid. He handed it to Ramirez, who peered at it closely. “Is this address correct?” he asked.

“No.”

Ramirez handed back the license and pulled out a small notebook and pencil. “Do you currently live in South Carolina, sir?” He’d probably already noticed that the Ford’s plates were from Oklahoma.

“Not anymore,” Jimmy answered.

“What is your current residence?”

Jimmy squirmed uncomfortably. “I, uh, don’t exactly have one. I’m… in transit.”

“In transit to where?”

“Sacramento. I might have a job there.”

“I see. Please tell me what happened, Mr. Dorsett.”

At least he was being polite and not condescending. And he stayed that way as Jimmy told his story. Ramirez asked some questions but only to supplement his notes. He didn’t seem to be trying to trip Jimmy up.

“Okay,” he said when Jimmy was done. “Just wait here, all right?”

Jimmy nodded. Where else was he going to go? He spent a long time fidgeting as Ramirez talked to the other cops and the EMTs. The truckers eventually grew bored and wandered back to their rigs. Jimmy was thankful he’d peed before the cops arrived, but fuck, he was dog tired. Pretty soon he was going to collapse.

The EMTs loaded Tom into the ambulance and drove away without lights or siren. The cops remained, and after a few more minutes, Ramirez briskly rejoined Jimmy. The officer didn’t look happy.

“Mr. Dorsett, do you know anybody in the Fresno area?”

“Not a soul.”

“I’m afraid I’m going to have to ask you to stick around while we investigate.”

Shit. “Investigate? He was old and sick and he died.”

“I know. And I don’t have any reason to doubt what you’ve told me. But we can’t just take your word for it. I’m sorry.” To his credit, he looked as if he meant it.

“How long?”

“Two or three days. We’ll need an autopsy, maybe some preliminary lab reports. And we’re going to have to impound your car as evidence.”

Jimmy moaned. “My car! Look, it’s all—”

“I know. We’ll get it done as quickly as possible—I’ll see to that personally. But again, it’s going to be a couple of days.” His expression turned stern. “When we search the vehicle, are we going to find any narcotics?”

“I don’t know what’s in Tom’s backpack, but you won’t find drugs anywhere else.” Jimmy had used when he was younger. Occasionally he’d used heavily. But he’d come to realize that drugs were the most toxic form of hope, lasting only a short while before leaving you worse off than before. He still drank now and then, but not often and usually not much.

After another assessing look, Ramirez nodded. “All right. Do you have enough money for a few nights at a motel? If not, there’s a men’s shelter downtown. Or the jail, but I don’t think that’s a good option.”

Jimmy tried to remember how much cash he had left. “How cheaply can I get a room?”

“Thirty-five a night, if you’re not picky.”

He had to chuckle at that. “I’m not. And I guess I can afford a night or two at that rate.”

“Good. I’ll give you a ride.”

“Yeah, fine.” Jimmy rubbed his face. “Can I have my bag at least?” His duffel bag contained all his worldly possessions other than the Ford: a few changes of clothing, a pair of decent work boots, an old knit hat, basic toiletries, a blanket and towel, and a couple of battered paperbacks he’d picked up somewhere.

“Sorry, no. But you can take a few things to get you through.”

So Jimmy had to endure the indignity of having the cops watch as he extracted underwear, socks, T-shirts, the plastic bag of toiletries, and a book. He watched as the duffel bag and trunk were shut up tight. At least Ramirez found him a larger plastic bag to carry his stuff. That was nice.

Jimmy had never before ridden in the front of a cop car. It was a crowded place, with a laptop and lots of buttons and dials for equipment he couldn’t identify. He controlled the impulse to poke things at random. He was lucky to be heading for a motel instead of the jail, and he really didn’t want to push his luck.

Ramirez took the driver’s seat and smiled at Jimmy before pulling away. “I appreciate your cooperation, sir. I know this is an inconvenience.”

“I guess I’ll survive.” Unlike poor Tom. “Will you contact his son?”

“We’ll do our best to find his next of kin.”

“What will happen to the body?”

“That depends. If we can find family, we’ll release the deceased to them. If not, we’ll see if he has any resources to pay for a burial.”

Jimmy snorted. “And when you find out he doesn’t?”

“Cremation, and storage for a time.”

After a short drive, Ramirez pulled off the freeway and onto what had once been the main highway, lined with motels apparently in decline since the fifties. The Comet Motel was a motor court whose faded neon sign sported a spaceship-shaped appendage with remnants of weathered paint. A pair of hookers waiting near the driveway waved at Ramirez, who waved back.

“Not exactly the Ritz,” Ramirez said as he stopped in front of the office. “But better than the shelter or the jail.”

At this point Jimmy would have slept anywhere. “Okay. Thanks for the ride.”

“Here’s my card. Call if you need anything or have any questions. You’ll hear back from me as soon as possible. I can phone you here. Just don’t skip town, all right?”

“I won’t.” Jimmy took the card and slid it into his pocket. Clutching his plastic bag, he climbed out of the car.

But before Jimmy could shut the door, Ramirez leaned over, hand outstretched. “Thank you again, Mr. Dorsett.”

Christ, this cop was a good-looking man. Under very different circumstances, Jimmy might have flirted with him. But all he did was give Ramirez’s hand a quick shake, then slam the door and walk away.

CHAPTER TWO

AFTEROFFICER Ramirez dropped him off, Jimmy checked in, paying his thirty-five bucks to a desk clerk with facial tattoos and nightmare teeth. Jimmy wasn’t surprised at the condition of his room, which was dirty and smelly and dark. Nor was he shocked to find a lumpy mattress that had probably been purchased while Carter was president. Which might also have been when the bedding was last laundered. Still fully dressed except for his tennis shoes, Jimmy lay down atop the hideous comforter, pillowed his head in his arms, and immediately fell asleep.

He slept deeper and longer than he expected, until his empty stomach awakened him midafternoon. Under the trickle of water that passed for a shower, Jimmy mentally designed brochures for the Comet Motel. He’d include glossy color photos of some of the highlights, such as the large dead roach he’d found in the tub, the mystery stains on the pink upholstered chair, the smear of blood on the closet door. He could include testimonials from satisfied customers: the drug dealer in the next unit, the man who stalked the parking lot and shouted warnings about aliens listening to people’s thoughts, and of course the neighborhood hookers. And gee, but the motel was conveniently located. After all, the trains passed by just yards away—many times a day—and the freeway was practically out your front door. And if you wanted a front-row view of gang activity, the Comet was your destination of choice.

It wasn’t that he hadn’t stayed in worse places; it was only that he hated emptying his wallet for a dump like this.

Freshly showered and wearing clean clothes, he went in search of food.

The sun’s glare scorched his eyeballs. The Comet and its surroundings looked even worse than they had in the early-morning light. Every bit of faded and peeling paint, rusty metal, and broken concrete stood in sharp relief. So did the feral-looking kids clustered at one end of the parking lot, playing with a ball and a broken shopping cart. Jimmy smiled at them, but they didn’t smile back. He hadn’t expected them to.

The Comet shared the street with several equally decrepit motels interspersed with weedy vacant lots and scabby-looking palm trees. A few blocks away, Jimmy found a gas station with an attached liquor store—handy for all of your DUI needs. But in addition to cheap booze, the place stocked some basic groceries. He chose a loaf of bread, aerosol cheese, a box of cereal bars, and a jug of water. His diet had been shit ever since he hit the road. He was probably going to get scurvy. But he couldn’t afford to eat out—not even fast food—and his in-room dining options were limited when he didn’t even have a fridge. He added a small carton of milk to his purchases. At least he’d get a little nutrition that way. He drained the carton while he walked back to the motel.

He was restless and would have walked farther, but the sun beat down and the scenery wasn’t very promising. Besides, what if the cops returned to the Comet and he wasn’t there? Would they assume he’d skipped town?

Shit, maybe he should skip town. The cops would find out soon enough that Tom died of natural causes, and then they’d stop looking for Jimmy. He didn’t care about anything in his car except for the boots, and the car itself was heading to the graveyard. But Officer Ramirez had treated him decently, had trusted him a bit, and Jimmy had given his word. He guessed he could stick around awhile longer.

Back in his room, he sprayed cheese product onto slices of bread, rolled the bread into tubes, and ate. It had been one of his staple meals during childhood, along with dry cereal, peanut butter and crackers, and ketchup sandwiches. Ramen soup if his brothers could be bothered to work the stove. Shit. It was a wonder he hadn’t keeled over long ago.

He washed his shirt, underwear, and socks from the day before and hung them in the bathroom to dry. He tried to stay clean whenever he could, and he hated being smelly. Dirtiness was unavoidable at times, especially when he had to sleep outdoors, but when he saw others draw away from him as if his filth and poverty were contagious, his heart hurt. He made special efforts at cleanliness when job hunting; nobody was going to hire a grimy bum.

Downtime with nothing to fill it was another problem with being transient and unemployed. That’s why he’d tried to cultivate blankness. He sat on the bed and tried to turn off his brain, but today he couldn’t achieve it. His mind kept whirring, nearly as noisy as the Ford. The ancient console TV had a wavering staticky picture and only a high-pitched whine. Finally he grabbed his book and began to read. It was an old Stephen King he’d read before but didn’t mind rereading.

Night fell. The noises outside his room became louder. A couple screamed at one another, and a baby cried. Cars sped by. Trains rumbled, shaking the entire building. Somewhere, from what sounded like the depths of hell, a woman repeated over and over, “You can’t stop it because it wants to stop you.”

And the cops didn’t show.

Although he wasn’t really tired, he eventually switched off the light and lay down, once again fully clothed. He dreamed of earthquakes and other natural disasters, and he dreamed of snakes.

HEHAD to pay another thirty-five bucks in the morning. The clerk didn’t look any happier about taking his money than Jimmy felt about giving it.

“Is there a grocery store somewhere nearby?” Jimmy asked.

“Gas ’n’ Guzzle four blocks that way.” The clerk jerked his thumb.

“Yeah, I was there yesterday. I was hoping for someplace that sells actual food. You know, the stuff without a million unpronounceable words in the ingredients list.”

The clerk pursed his lips and shook his head.

“Okay,” Jimmy said. “You have a nice day, now.”

Out in the parking lot, he spied the kids. He was pretty sure they should be in school, and any adult supervision was evidently done by stealth. Jimmy knew from his own childhood that kids like these usually had a good lay of the land. “Hey,” he said, addressing the oldest one, a grubby boy around nine or ten. “Where near here can I buy groceries other than the Gas ’n’ Guzzle?”

The kid narrowed his eyes. “Why?”

“’Cause I’m tired of spray cheese.”

“Gimme five bucks and I’ll tell you.”

By now the other children had clustered around, eager to be entertained or enriched. “An entrepreneurial spirit,” Jimmy said. “I like that. But I don’t have an extra five dollars.”

“Then I ain’t gonna tell you.” The kid crossed his arms.

“Tell you what. You give me good directions to a supermarket, and when I get back I’ll juggle for you.”

The kid raised his eyebrows skeptically. “Juggle?”

“Yep. While I’m gone, you find three juggleable objects. That means nonlethal, not too big, and not too heavy.”

The younger children chattered excitedly with one another, considering what things they could find, but their leader had a don’t shit me expression. “How do I know you can really juggle?”

“You don’t. But even if I can’t, you get to watch me toss stuff around like an idiot, and that’s worth at least five dollars.”

“Yeah, but what if you get back and you won’t do anything at all?”

Jimmy shrugged. “You’ll just have to trust me.”

The kid’s face clearly articulated how much he trusted adults. Jimmy couldn’t blame him. He’d be willing to bet the last of his cash that this boy had gone through plenty of demonstrations that grown-ups were lying, unreliable assholes.

“What have you got to lose, bud? If you don’t give me the info, I definitely will not juggle. But if you do, I might. Odds say you’re better off spilling.”

After mulling this over for a few moments, the kid nodded. “’Kay. But you better not be lying.”

The grocery store was about a mile and a half away—a dusty walk past tired little houses with bars on the windows and doors. The store was small, with scuffed floors and an unpleasant smell of rotten food. But their selection was considerably larger than the Gas ’n’ Guzzle’s. He bought a couple of pull-tab cans of tuna and a box of crackers, a few small apples, a bag of almonds, some protein bars, and another small carton of milk. He could have done better if he had access to a hot plate or even a coffeemaker. He could do a lot with hot water.

The bag grew heavy as he carried it back to the motel.

He greeted the hooker at the parking lot entrance. The gang of children waited for him. “We found stuff for you,” announced a girl who was missing her top front teeth.

“Great. Let me put this away first.”

They clearly didn’t want to wait, but he marched past them, unlocked his room, and set the paper bag onto the stained chair. Then he went back outside. “Okay. What have we got?”

They gleefully showed him the objects: a busted wooden baseball bat, a slightly mushy grapefruit, and a bald and naked imitation Barbie doll. “That’s quite a collection.”

“I bet you can’t do it,” the oldest kid said with his chest puffed out. Jimmy imagined him in another decade, buff, inked, picking fights with the world. At least he wouldn’t get pushed around.

Jimmy smiled at him before picking up the three objects and testing each of them in his hands, getting a feel for their weight and balance. Then he juggled them.

He was pretty good at this. It was a skill someone had taught him years ago, when he and his mentor had been looking for a way to pass the time. The guy who taught him wasn’t actually all that talented at it, but Jimmy practiced. It was a good way to kill twenty or thirty minutes, and it didn’t require much in the way of supplies. Once or twice when he was passing through a larger city and hard up for cash, he had set an empty paper cup on the sidewalk and tossed around whatever was handy—keys, a shoe, a book, rocks, a piece of broken plastic something. He’d earned enough quarters for coffee and fast food.

The kids watched raptly, cheering when he got everything going really high. He kept the round going for a few minutes, then caught the items and took a deep bow. His audience clapped. For a brief time, all of them—even the tough oldest one—looked like happy little kids. He knew that wouldn’t last long, but he figured that even a fleeting moment of joy was worthwhile.

“How did you learn to do that?” asked the boy.

“I was in the circus. I juggled flaming torches while riding an elephant.”

The kids were wide-eyed. “How come you ain’t in the circus no more?” asked a younger boy.

Jimmy smiled. “Traumatic lion incident.” With a final jaunty little salute, Jimmy exited stage left. His tuna and crackers were waiting.

NEITHEROFFICER Ramirez nor any other members of Fresno’s finest showed up that afternoon. Well, not for him, anyway. At one point in the late evening, while Jimmy was munching an apple and lost in the Overlook Hotel instead of the Comet, particularly strident shouts rang out from the parking lot. The screams grew louder—until gunshots abruptly cut them off. Jimmy instinctively rolled off the bed and hugged the floor. A stray bullet was a pointless way to die. Within a short time, sirens shrieked. More yelling ensued, followed by silence. He hoped nobody else had been shot.

“You Torrances are weenies,” he said to his book when he was on his feet again. “I’d take a bunch of ghosts any day over fucktards with guns.” Haunted motels. What a load of bullshit.

He couldn’t get back into the book after that. He sat on the bed with his back propped against the splintery headboard and considered his immediate future. He couldn’t spend forever sitting around and waiting for Ramirez to show up. Maybe he should find a job here. Find a place to live—a room in someone’s house or a slightly better motel room he could rent by the week.

But the plan, such as it was, didn’t sit right. He didn’t have anything specific against Fresno. It wasn’t glamorous, but he’d seen worse. Yet he really didn’t want to stay. This city itched him like scratchy wool clothes. Most places did, eventually, but he felt it here already after only two days.

He needed to go.

One more day, he decided. If Ramirez didn’t make an appearance within twenty-four hours, Jimmy would hitch a ride or hop a train and get the hell out of Dodge. He’d keep on moving until the itch subsided. For a while.

He took another shower, his second that day, as if he could bank the excess cleanliness for later. He folded the clothes he’d washed the day before and tucked them into the bag Ramirez had given him. He counted the thin stack of bills in his wallet. And he tried to go to sleep.

But someone was arguing nearby. No gunfire this time, just rage and fear. A train rushed by, blowing its whistle, shaking the entire motel. And his brain was too stupid to turn off obediently. It churned unevenly, throwing out random bits of memory before settling on one memory that was recent and not random at all.

You still got time, Tom had said.

Yeah, Jimmy had almost nothing but time. Time, a book, a couple changes of clothes, some toiletries in a plastic bag, a few groceries, and about a hundred bucks. Tom said he should use that time to fix things. Screw that. Nothing in Jimmy’s life needed fixing. Well, nothing except that Ford, and even if he could afford it, the damn thing probably wasn’t worth saving anyway.

Jimmy knew nobody would envy his life. But it was his, not anyone else’s. And he had no regrets. Sure, he’d made bad choices. Done stupid shit. He’d ended up in jail a couple of times; he’d blown good opportunities. He’d fucked men he shouldn’t have and didn’t fuck men he should have. He’d made a lot of wrong turns.

And there was the stuff he hadn’t done. No relationships. No real friendships. No school past tenth grade. No home beyond the temporary. He’d never been important to anyone.

Someday he was going to die like Tom—alone, maybe on the road. Nobody would give a damn, except for whatever unlucky schmucks got stuck with getting rid of his corpse.

But fuck if Jimmy was going to sit here feeling sorry for himself, and he sure wasn’t going to run around trying to undo things long since done. He’d never had any kids to abandon, never had anyone to let down. If he wanted to live his life as a drifter—and he did—that was his own damn decision to make. He didn’t owe anybody anything.

With his makeshift meal sour in his stomach, he rolled over and tried again to fall sleep.

CHAPTER THREE

RAMIREZDIDN’T show up the following morning, which Jimmy spent sitting on a big upturned plastic bucket outside his room, watching the kids run around the parking lot and the early hooker shift try to pull customers. Around noon, a man wandered over to join him. He probably wasn’t older than thirty, but he looked tired and used up. His no-color hair hung lankly over gray skin, and his brown eyes were muddy and faded.

The man leaned against the wall before he took out a cigarette, lit it, and took a drag. “You just get out of jail?” he asked. Maybe he’d seen Ramirez dropping Jimmy off—although the cops didn’t usually chauffeur people who’d just been sprung.

“Nope. I haven’t done time in a while.” And never for very long. His crimes had been petty ones: vagrancy, trespassing, that ilk.

“What’re you doing here?”

“Just passing through.”

The man spat and took another deep drag. “I been here seven months. Me an’ the kids.” He gestured vaguely at the children. Surely they weren’t all his, but he didn’t specify. “It’s a shithole.”

“It could use a little updating,” Jimmy said mildly.

“I used to own a house. Nice little place, and we kept it real clean. I had a decent job in construction, you know? Then the economy went belly-up. We lost the house. I was real happy when I finally found a job, but then I got hurt. Fucked up my back. And my wife….” He sighed, then tapped his head. “She’s got problems in here, you know? She’s been in the state hospital up in Stockton for a while. But she’ll be getting out soon.”

Jimmy knew this story—or ones very like it. Families like this never seemed to get a break as the miseries piled up. And even when things went well, they lived so close to the edge that all it took was one small shove, one little misfortune, to push them over.

“I hope things work out for you,” Jimmy said.

“Yeah, we’ll be okay. After Rosie gets out, we’re gonna go up north, us an’ the kids. It’s this fucking place that makes her crazy. Up in Oregon, Washington, she’ll be better. And there’s lotsa good jobs too. We’ll buy us another house….” His voice petered out as if his dreams stopped there. Or maybe he realized that he was hoping, and hope was poison.

“Good luck with it,” said Jimmy. He went back inside his room to read.

RIGHTAROUND the time Jimmy started thinking about dinner, someone knocked confidently on his door. He’d already paid the day’s thirty-five bucks, so he knew it wasn’t the desk clerk—who hadn’t looked as if he had the energy for knocking anyway. So Jimmy wasn’t entirely surprised to open the door and find Officer Ramirez.

“I’m sorry it took so long,” Ramirez said. “Our coroner was being thorough.”

“No problem. Can I have my car back?”