12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Northway Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

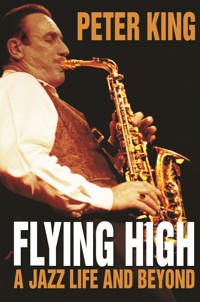

Peter King's book ranks among the great jazz autobiographies. One of the world's leading alto saxophonists, he tells his story with searing honesty, revealing the obsessions and motivations that have driven him and the dilemmas of surviving as a top creative musician in an often inhospitable world. With unsparing self-analysis he describes the traumas that accompanied his brilliant career for many years. Internationally recognised as a jazz star, Peter King has performed and recorded with a galaxy of musical legends, many of them his close friends. Among those vividly recalled in this book are Bud Powell, Milt Jackson, Ray Charles, Anita O'Day, Elvin Jones, Max Roach, Hampton Hawes, Al Haig, Philly Joe Jones, Zoot Sims, Jimmy Witherspoon, Dakota Staton, Red Rodney, Jon Hendricks, Tony Bennett and Marlene Dietrich. But while the story here centres on Peter King's life in jazz it shows other important sides of him too: his ambitions and achievements in classical composing, his interests outside music (he is a leading figure and writer in the aero-modelling world) and, above all, the treasured personal relationships that have sustained him through a turbulent life. Flying High tells of an exhilarating high altitude journey, in the jazz world and beyond. "A highly personal but hugely readable chronicle of a quietly spoken genius, this is a no-punch-unpulled diary of a young man who found himself at the UK core of a vital new music which rattled the mainstream and shook the floors of jazz clubs from New York to London in the fifties. King's vividly remembered and often brutally detailed story makes a book whose appeal far exceeds the jazz cognescenti and is by turns funny, touching and, dare I say it, unputdownable! A wonderful and historically fascinating self-portrait of an artist whose restless mind embraces far more than the achingly beautiful music he continues to produce." Ian Shaw "Peter King paints a unique portrait of the London jazz scene over the past fifty years. Beautifully observed portraits of jazz legends (both American and British) are enhanced by fascinating anecdotes that give a rare insight into the art form that is jazz. The book could only have been written by a maestro of Peter King's stature and for me it was a complete 'page turner'. I couldn't put it down and read it in two sessions. I already have a place on the bookshelf for it, alongside Music is my Mistress (Duke Ellington), Really the Blues (Mezz Mezzrow), Straight Life (Art Pepper) and Beneath the Underdog (Charles Mingus)." Mike Figgis "Peter King has written an account of himself which is not only compelling, but touching in its honesty and openness. In much the same way as he plays a solo he gives you everything, in detail... This book is filled with the wisdom of a true master, and should be an obligatory read on the curriculum of all music schools and colleges. It is full of insights into the stuff that cannot be taught in a conservatoire. It describes the dedication and devotion needed to attain the level of playing that few manage to get to. It is a must for anyone seriously engaged with improvised music, whether it be jazz or any other musical category... He has captured himself on paper and the book really feels as though it is him sitting there talking to you. Peter King has a great story to tell, it is the story of a survivor. It's a real slice of life, his life, and a big one at that." Stephen Keogh, LondonJazz

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Flying High

A Jazz Life and Beyond Peter King

Foreword by Benny Golson

www.northwaybooks.com

Copyright © Peter King 2011, except for Foreword, © Benny Golson, 2011.

ISBN (pbk) 978 0 955090 89 9

ISBN (ebk) 978 0 992822 20 0

Ebook edition 2014. Conversion by leeds-ebooks.co.uk.

The author has asserted his right to be identified as author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Cover design by Adam Yeldham of Raven Design. Cover photo of Peter King at the Theater De Tobbe, the Hague, in 1995 by Rene Laanen.

In memory of Linda

CONTENTS

Foreword by Benny Golson

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Coda

Appendix

FOREWORD

I first heard Peter King play in 1964 at Ronnie Scott’s Club in London. He was playing the tenor saxophone then, and, because of the way he mastered it, I readily assumed he was a tenor player. The way he played absolutely astounded me. He was bungee-jumping and sky-diving with the determination of a daredevil. Though I was overwhelmingly impressed, I somehow did not make myself known, but he left an indelible and lasting impression on my psyche that evening.

It was only a few years ago that we finally met. We were thrown together in a European saxophone group. It was then I began to know the length and breadth of this talented man. I discovered that he was really an alto saxophone player. However, the kind of saxophone he played was immaterial since the notes emanating always reflected the same thing – extraordinary talent underscored with a cognitive mind.

What makes Peter King who he is? I think I know. He draws upon boundless imagination. But why is this important? Actually, it’s not only important but essential in the creative process. Creativity is essential to everything that moves ahead in the realm of time and concept. It’s as a door to the future, a future that will always have an indistinguishable face, but because of curiosity and axiomatic talent, we can sometimes give it a face of our own making.

Imagination is preceded by curiosity. We intuitively think, ‘What will happen if I do this?’ ‘Will this work with that?’ Curiosity gives birth to imagination. If something comes into existence bereft of imagination, it is usually somewhat limp of conviction. But why is imagination ever so important? Because it’s a precursor to giving ‘birth’ to creative thoughts – yes, creativity. It gets the monster up off the table as a living, breathing thing as we symbolically scream, ‘It’s alive!’

How does Peter King factor into all of this? He is the embodiment of these things. But don’t all creative people experience and live this? Yes, of course, but not always on the deepest level possible. Peter does, which, in part, makes him distinctive, separate and aside from so many. I’ve heard his memorable rendition of ‘Body and Soul’, the most recorded song ever. It not only reaches the ear and heart, but goes to the deepest grotto of that heart’s core. It’s also a reflection of a plethora of imperial dreams causing his saxophone to speak with a voice like no other.

Peter is not satisfied with endlessly serving the same warmed-over dish time and again. Thus, he walks with one foot in the present and the other in the future, looking for things awaiting his discovery and giving them a name and direction never before known. This takes courage. New things, that is, things never before heard or seen, sometimes are met with disapproval because of unfamiliarity, suspicion and doubt. So, Peter, and those of similar ilk, must be brave of heart, but never arrogant because this fouls the air we breathe. He is aware of this, which explains his wonderful character as a man, a person, a functioning human being in a society of other humans. He is not only an exceptional saxophonist whom I admire, but a personal friend whom I hold in the highest esteem.

He is bent on moving ahead to the ‘next something’, whatever that might be. It’s this mind-set that keeps him on the cutting edge of this music we lovingly call jazz. It’s no easy feat, but he’s mastered the ability to pull stars from out of the sky, taking them into precious possession as his own, and doing with them as he sees fit to the benefit of us all.

All of the foregoing is exemplified by his many recordings and performances that monumentalize who and what Peter King is. It’s a part of his being that he is generously and mercifully sharing with all awaiting ears and hearts as he invites us to share his musical universe.

Real talent has no quadrilateral boundaries. Peter’s talent, then, does not end with explorations of his saxophone. His pen readily obeys him also. He is a composer of consequence, having recently written a full-blown opera. A daunting undertaking which exists within another realm, dense of thought and concept on yet another level.

Though I’ve made use of many words here, no prolixity of words is really necessary in order to explain the likes of Peter King. He is a genius whose certainty far outweighs his doubts.

Benny Golson

New York City

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book could never have been written without the help and support of many people and I would like to acknowledge my debt of gratitude to them all. I wish I could list everyone but space does not permit, so my apologies to all those who are not mentioned.

Firstly, without Ann and Roger Cotterrell’s faith in me this book may never have been published. Their patience, kindness and advice have been an enormous help, as has their knowledgeable and sensitive editing of my original manuscript. Working with Ann and Roger has been a fascinating and rewarding experience.

Writing a book, like writing an opera, takes many months of hard work and my dear friend, Julian Barry, was there for me throughout the long process of writing both this book and my opera Zyklon, for which he wrote the libretto. Julian has immense experience as a playwright and as a Hollywood screen writer. His wonderfully concise advice and continuing encouragement were invaluable. I’m also deeply indebted to Stacy Ann Ralph. Stacy not only read the first draft but also helped me improve my writing technique. Both Stacy and Julian gave me very useful and honest advice on certain issues that arose during the lengthy editing process. I also wish to thank my dear sister, Brenda Bainton, especially for her invaluable memories of my first days on this earth.

I am honoured and very grateful to Benny Golson for his eloquent foreword and I would also like to thank Ian Shaw and film director Mike Figgis for reading the original manuscript and then contributing glowing recommendations to help promote it.

My dear friend, Dr. Sheldon (Shelly) Hendler, deserves special thanks. He personally knew many of the jazz giants and was a close friend of Red Rodney and also his doctor. As well as doing brilliant work in medicine and biochemistry, Shelly is an excellent musician. He was a great source of information in writing the book, particularly the sections on Bud Powell, sharing with me his knowledge on Bud’s medical condition and treatment. Through his contacts with the late Leon Parker, Charlie Parker’s son, he also has a unique copy of Bird’s complete medical records.

I’d also like to thank Verne Christensen, another great friend who lives in Kansas City and has great knowledge of the jazz scene there and its history. Without his energy, passion for jazz and promotional skills, I would never have been invited to play at the Charlie Parker celebrations in K.C., along with Max Roach, Milt Jackson and many other jazz legends.

Thanks are also due to the following friends who helped clarify the accuracy of facts in the text: Kim Parker helped with certain passages about her mother, Chan Parker. Tony Kinsey, Spike Wells, the late John Dankworth, Alec Dankworth, Stan and Clark Tracey, John Horler, John Miles, Martin Dilly, Del Cooper, Dennis Higgins and many others, all helped refresh my memory about events long in the past. Phil Woods shared with me his fascinating reminiscences of when he and other famous American musicians flew model aeroplanes in New York’s Central Park, back in the early fifties. Special thanks too to Hardy Brodersen, who not only shared his experiences as a schoolboy friend of Lucky Thompson and Milt Jackson in Detroit, but also gave me information on famous Hollywood film stars of the forties and fifties who were also aeromodellers.

Last, but not least, I wish to thank all those friends who helped by reading the first draft of the manuscript and giving their opinion, encouragement and sometimes useful additional information. They include Michael Barham, Linda Masters, Haydn Bendall and Wally Evans (British representative for Yanigisawa saxophones and Rico Reeds).

1

‘Blood on the walls! For Chrissakes, Pete, look, those are blood spots, all over the damned walls!’

‘What d’you mean? What are you talking about?’ I snapped back.

The guy who rented me the depressing room in Glebe Road, Barnes, where I was living, along with drummer Phil Seamen, was pointing to several small dark red spots all over parts of the wallpaper that formed a backdrop to the chaos that had become my life. He was accusing me of causing them! I tried frantically to dismiss his accusations but an awful truth had already forced its way into my mind. The monster that I thought I had under at least partial control, had in fact taken over my life. It was now destroying me and all my hopes of advancing my career as a musician. This could not be happening to me, could it? The truth is, it was.

When I decided to write this book I soon realised it would be difficult to tell my story truthfully without describing, for the first time, my struggle against a demon that almost wrecked my career and nearly killed me. This ‘demonic shade’ became such an all-pervading part of my life that it controlled almost everything I did. Having successfully rid myself of this threat to my very existence many years ago, I feel the time has come to bare my soul and finally lay its evil ghost to rest, once and for all. Writing this autobiography has not been an easy task. I have had to relive long forgotten nightmares as I delved back into the story of my life. It has also raised questions about how my experiences in infancy and in childhood may have affected the rest of my life.

Was it the terror of loud noises while, as a baby, I cowered night after night in the Anderson Shelter during the Blitz as the nearby ack-ack guns blazed away at the Nazi bombers above? Was it the fear of not living up to my elder brother’s brilliant academic career? Was it the humiliation of still playing in Tubby Hayes’ big band while everyone knew my wife at the time was blatantly sleeping with him?

Any one of these things could have eventually caused an over-sensitive person to seek solace in whatever could best take away the pain. But, difficult as they were for me, bad events are just part of any normal life. People adapt to them and survive much worse things without damage. Probably those events are just a way of justifying to myself why I took such a self-destructive wrong turn at a formative stage in my life.

But I overcame my demons – this book is about how music and musicians have given fulfilment, happiness and meaning to my life. Overall I’ve had wonderful experiences, I’ve made great friends and above all I had the long-term love of a woman who stayed by my side through good and bad times.

And yet still, as I write this, other horrific memories flood back into my mind and I wonder how on earth I arrived at that dreadful crisis in my life and how I ever fought my way back from the abyss that threatened to engulf me. We are all influenced by our experiences in childhood, but perhaps events long before we were even born can have profound effects on us too. After all fate is a strange thing – if my paternal grandfather had not been killed while working on the railroad in Harrisburg Pennsylvania, I might have been born an American.

* * *

In 1912 my father, Edward Horace King was thirteen years old. His father and mother had decided the family should emigrate from West Ham, in the East End of London, to America. They crossed the Atlantic steerage class on one of the big transatlantic liners and took a train from New York to a new life in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Here my grandfather worked in the railway marshalling yards, riding the big shunting locomotives that prepared those amazingly long American freight trains for their journeys. He worked hard and things were looking good until, after only a few months, tragedy struck. As he stood on the front of one of the big locos one day, preparing to hook up wagons, the engine jolted over some points. He was thrown onto the track and the engine ran over him, killing him outright. It was quite a local tragedy and my grandmother, Amelia King, and my father were left to fend for themselves in a foreign country, three thousand miles from home. Eventually the Salvation Army helped them to get back to London as, although Dad managed to get work, he couldn’t save enough to pay their passage. In later years, my mother and father would always give money to the Salvation Army if one of their bands played in the street. It was my dad’s way of saying thanks.

Not long after my father’s return to the UK, the First World War started and in 1916 he enlisted in the Grenadier Guards after a woman gave him a white feather. This obnoxious practice was rife during the so-called Great War. If a girl gave you a white feather it meant she thought you were a coward, because you had not volunteered for Kitchener’s army. My father was just seventeen and therefore under age, but pride made him do what many other young men did. He lied about his age and enlisted. After basic training he was sent with the British Expeditionary Force to Belgium, where he was briefly involved in the second great battle of Ypres. He only managed three weeks in the trenches before being invalided out. Up to his waist in water, mud and corpses, he soon succumbed to what they called trench fever, caused by the filthy water, rats and rotting flesh, and as antibiotics were unknown then, this new strange illness could be a killer. Dad spent eighteen months in hospital recovering. He was also mustard-gassed. A gas shell landed in the trench, a few feet away from him, but didn’t explode. The shell casing cracked, pouring its contents into the trench. The garlic-smelling, semi-liquid gas covered his hands, causing excruciatingly painful blisters. He also got some of the stuff in his lungs and suffered from a bad chest for the rest of his life.

I often wonder whether, in an opposing enemy trench, Adolf Hitler, then a young corporal in the German army, may have been close by. Hitler was also mustard gassed and temporarily blinded in Ypres. Once my father had recovered, he used to stand guard outside Buckingham Palace in his red Grenadier Guards uniform and bearskin hat. He told me that at six feet in height, he was the shortest guy in the squad and was nicknamed ‘Shorty’. His seven feet three inches tall regimental sergeant major, who had a fourteen-inch ‘handlebar’ mustache, would pick on any poor soldier who forgot to get his ‘short back and sides’ bellowing out things like, ‘Am I ‘urting ya son? Well I oughta be ‘cause I’m standing on yer ruddy hair!’ Or, ‘You may break your mother’s heart but, you won’t break mine!’

After his release from the army, Dad co-ran a shoe repair business until his partner did the dirty on him and left him without a viable business. He became a tea boy at Unilever House, where he worked his way up, eventually being promoted to advertising manager. By the time he retired, he had driven nearly a million accident-free miles as an advertising representative at Lever Brothers, without ever passing a driving test. He had to teach himself – Unilever gave him a brand new car one Friday night and just told him to get on with it! When driving tests were later introduced, anyone who had already learnt to drive was given a full licence without a test.

Not long after the war, he married Winifred Baldwin, my mother. She was the only surviving girl from twelve children. Her five sisters all died in childhood. Of her six brothers two were killed in the Great War and another also died young, of tuberculosis. My uncle Bill also suffered from TB later in life. That left my uncle George and my uncle Alf. My mother and her remaining brothers all died of heart disease in their sixties but my father’s mother, Amelia, lived to the ripe old age of ninety-three. For most of her later years she was totally blind and profoundly deaf but she had a wonderful ‘Cockney’ spirit and would cheer herself up by endlessly singing old music hall songs. The only trouble was she took a wicked delight in singing them while her family were trying to watch television. Not being able to see or hear the new invention, she could not understand why anyone else should enjoy it better than singing along with her!

Uncle Alf had an important influence on my love of music. He was an excellent amateur pianist, could read music and played in the style of Charlie Kunz and Zez Confrey. I remember him teaching me to play ‘God Save the King’ with my nose, a trick he performed at parties. My mother played the piano quite well when she was young but my father, who played a bit of ‘pub’ piano, was the one sought after for sing-songs. I think my mother lost interest in the instrument, receiving so little encouragement. I hardly ever heard her play, although we always had sheet music and a piano in the house. She led a frustrated life in many ways, despite Dad being a loving husband and father.

My elder brother, Edward, was born in 1925 and my sister Brenda in 1929. Teddy was always the high-flyer in the family. Educated at Kingston Grammar School and the School of Oriental and African Studies, he was fluent in over forty languages, from Sanskrit to Lithuanian and from Swahili to Russian. In the Second World War he was in the Intelligence branch of the Royal Navy in the Far East as a member of Lord Mountbatten’s staff, where his fluent Chinese was a great asset. I finally arrived, a late accident, in 1940.

In the mid-1930s my parents moved to a new semi-detached house in Tolworth, near Kingston upon Thames, Surrey. The area was being built up from virtually open fields into one of the many new outer London suburbs. The family settled into a contented lower middle class existence but then, in 1939, the Second World War broke out. Sometime in that November, I was conceived. For my parents and especially my mother, who was then in her forties, this must have been a shock and a considerable inconvenience. One can only speculate what traumatic thoughts went through her mind while she was carrying her new addition to the family. During the ‘phoney war’, anti-German propaganda was rife and I know she was badly affected by a cinema newsreel purporting to show Nazi SS bayoneting mothers in the stomach at a maternity hospital in one of the occupied countries. Total lies maybe, but my parents wouldn’t have known this at the time and in view of the scale of Nazi atrocities by the end of the war, it might as well have been true. People were expecting Hitler to invade Britain at any time and the general fear and tension can only be imagined.

My mother went into labour just as the phoney war was drawing to a close and I arrived at 2 p.m. in the afternoon of 11 August. When my father returned to Kingston Hospital later that evening he found the floors and stairs stained with blood from casualties who had been hit by stray bombs. Adler Tag (Eagle Day) with Hitler’s all-out assault on the RAF followed on 13 August.

My mother always had a nervous disposition and – although I seem to have inherited most of my genes from my father (I have a strong resemblance to him even down to his slightly deformed size twelve feet) – I definitely inherited my mother’s genes as far as my mental make up is concerned. On the first of many childhood visits to a psychiatrist, my parents were told my troubles started in my mother’s womb, before I was even born. Not a good start for any kid.

I don’t remember ever being frightened of bombs, but I did have other fears, which I remember vividly from a very young age – the kind of things that stick even in the mind of a baby. One episode couldn’t have helped much, though it has its funny side. I don’t recall it but my sister told me about it on my sixtieth birthday. One night mom had bathed and powdered me, changed my nappies, and generally tarted me up. Just as she finished, the damned air raid siren sounded and we all trooped down to the Anderson shelter in the garden. We had only been there a short time when a stray bomb exploded in the allotment next to the house. It was about fifty yards away and blew all the windows out. That was frightening enough, but what made my mother really blow her top was the fact that the shit from the roof of the shelter showered down and covered us all from head to toe. Looking at her freshly bathed baby covered in filth, she saw red and screamed at the Nazi bombers, ‘You bastards! I’ve only just bathed him!’ She wasn’t concerned about the blown-out windows nor the fact we had just missed annihilation. She was just incensed that those Nazi sods had dared to cover her baby in shit after all the work she had done cleaning him up!

My own earliest memories of the Blitz were of being woken up night after night to have my dressing gown put on before being carried to the garden shelter. The two things that really freaked me out were gas masks and loud noises. Apparently they tried to put me into one of those claustrophobic baby gas masks, the ones you put a whole child in. They never did manage it though, as my hysterical screams persuaded them I would rather take my chances without it. Later, when I was a toddler, they tried unsuccessfully to get me to wear one of the kids’ gas masks. These were supposed to be less frightening than the adult ones, because they were brightly coloured and had Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck faces. But they didn’t impress me one bit and, as I had realised by then that screaming blue murder usually made the grown-ups relent, I put up such a fight they gave up. My poor parents must have been beside themselves by now. Not only would I not wear any kind of gas protection, but I wouldn’t let anyone else either. I wouldn’t go near the shelter unless all the gas masks, Mickey Mouse or otherwise, had been removed. For a sensitive kid, those damned things were scary and people wearing them looked like the dreaded bogeymen that naughty kids were threatened with.

As a toddler it seems I also suffered from what they called ‘night horrors’. These manifested themselves in strange ways, although I have no recollection of them. It seems that one night I was found trying to climb out of the upstairs bedroom window while still asleep. The other thing that scared me to death was any kind of loud noise. Except for the one stray bomb, we were fairly safe in Tolworth, but about two hundred yards away there was an anti-aircraft battery in the local park. The ack-ack guns made a horrendous din as they tried, mostly unsuccessfully, to shoot down the nightly raiders. I dreaded them and Mum used to cover my ears as best she could when they started up. Right up till my early teens I would jump a mile at things like fireworks or cars back-firing, because of those guns. It might not have been so bad if they had shot down a Heinkel or two, but the only thing they seemed any good at was terrifying the local kids.

My sister Brenda was educated at Surbiton High School for Girls, but wasn’t too interested in furthering her education after she matriculated. In fact she suddenly decided she wanted to study aircraft maintenance, of all things. She had a textbook on the subject, full of wonderful diagrams and drawings of the inner workings of aircraft and engines. This and her wartime aircraft recognition books probably led to my fascination with aeroplanes. From the age of about four, I started learning how to spot planes, using the little silhouette plans in her books. I remember being upset just after the war when I asked my father why I never saw any Messerschmitt 109s or Heinkel 111s. Dad told me, ‘Oh, you won’t see any of them now, son.’ The war was over and I had missed the fun, just when I was beginning to enjoy it!

Mum and I were evacuated a while in 1944, during the doodle bug raids on London: V1 flying bombs and V2 rockets rudely interrupted the comparative peace at home and caused much death and destruction late in the war. We lived in Gloucester with a family whose son, Paul, was a little older than me. He was the proud owner of a beautiful model locomotive, powered by real steam. He was like an elder brother to me. I sorely missed my real brother, who was always overseas somewhere. Paul would sometimes scrape pocket money together to buy wonderful-smelling purple liquid called methylated spirits, with which he would fire up the locomotive to show me how it worked. I was thrilled to bits and soon got into model trains myself, but all we could afford were the old Hornby clockwork kind. One night Paul tried to show me a model of a doodlebug he was making out of plasticine. His mum got really mad at him, telling him not to frighten me with such terrible things, as I was far too young. I couldn’t understand what the fuss was about and told her I wasn’t scared. After a conflab between his mum and mine, I was allowed to watch him finish his model. The seeds were sown for my later passion for model aeroplanes.

Once the war ended my parents had to think about my education. My first experience of primary school was miserable. I made few friends, learnt very little and was soon moved to a tiny private school, Berrylands College. I was much happier there. The headmaster, Mr Sylvester Savigear, was an intellectual oddball, with several young daughters, all named after Greek goddesses. He was a very good teacher and taught most of the subjects himself to the older pupils. The only problem was that, although it was a mixed school, it seemed biased towards the female students. We had to play netball and rounders instead of basketball and cricket, which I found embarrassing and frustrating. I had some good friends there though and one girl, who seemed to take a fancy to me, persuaded me to have lessons from her piano teacher. I hadn’t yet fully appreciated the special attractions of the female sex, but I do remember two girls who aroused nascent adolescent feelings. One had beautiful long blond plaits and her name was Linda. I have loved that name ever since and my second wife turned out to be another Linda. I went every week to piano lessons and practised but my latent passion for music had not yet emerged. After a while the lessons stopped, but I always regret not continuing. The piano is difficult to learn once you grow older and a good knowledge of keyboard technique is invaluable for any serious musician, especially if you want to compose.

Eventually I passed the old eleven plus exam with flying colours and gained free entrance to Kingston Grammar School. This was my father’s first choice as he wanted me to follow in my brother’s footsteps. After the war, Dad’s job no longer required him to travel and, although he had been promoted, his loss of a firm’s car meant he was worse off financially than before. Teddy had been a private pupil at the school but my father could no longer afford to pay fees, so it was a relief when I passed and got a free place there. But this turned out to be a mixed blessing in the end and I felt a subtle but constant pressure to match my elder brother’s illustrious career. This would eventually lead to a crisis and a serious clash between us.

By now my sister was a bright teenager. Brenda loved to dance, especially the jitterbug, and had a good collection of swing records. I remember hearing the Harry James band, the Squadronaires and Glenn Miller around the house. In the later part of the war, Brenda had a crush on a handsome RAF fighter pilot, Peter Hickson, and I remember tagging along with her to see his parents in Surbiton. They kept rabbits, a handy thing to have during wartime food rationing. I adored the little things but they probably ended up in the cooking pot, as rabbits were one of the few sources of meat in those days. Peter was tragically killed when his Tempest Mk 2 crashed while flying home from Germany, only a few weeks after the end of hostilities.

In the early 1950s Brenda fell in love with and married Alan Bainton, a handsome young blond-haired man with an endearing Wiltshire accent, who was a great dancer and jitterbug partner. He had been a paratrooper dropped into Denmark at the end of the war to fight the retreating Germans. Afterwards he served in Palestine, trying to keep the peace before the founding of the state of Israel. When, later, my second wife’s mother first met him and learned that he had been a stonemason after his military service, she said, with a concerned look, ‘Oh how wonderful. But I suppose that’s a dying trade, isn’t it?’ She couldn’t understand why we all fell about laughing, until the penny dropped and she burst out giggling herself. Maybe Alan had seen the light too because, shortly after marrying my sister, he enrolled at the Metropolitan Police Training College at Hendon and gave up stone masonry for good.

At Kingston Grammar, I did well with my studies for the first couple of years, mostly keeping near the top of the class. There wasn’t much bullying either. I was in the ‘A’ stream, where the supposedly brightest kids were and most of the rougher boys were in the ‘B’ and ‘C’ streams. I made friends easily, something I had had trouble with earlier, being painfully shy, and I also began to enjoy sports.

As soon as we enrolled, we were asked if we wanted to take up a musical instrument. I had become very interested in my brother’s classical record collection and would go round the house doing imitations of Benjamino Gigli, the great operatic tenor. God knows what that must have sounded like! I copied my brother’s antics as he would flail his arms about ‘conducting’ his favourite recordings of Beethoven’s Fifth and Handel’s Messiah. I fell in love with the violin, and had fantasies of becoming a world famous violinist. In fact I was going through a phase of hero worship for anyone world famous. Just ‘famous’ didn’t do it for me. My heroes ranged from Stanley Matthews through Don Bradman, Denis Compton and Captain Scott (the ill fated Antarctic explorer), to piano virtuoso Solomon (Solomon Cutner) and other musicians, sportsmen, explorers and artists. My father encouraged this, taking me to cup finals at Wembley, test matches at Lords and the Oval and telling me about his favourite heroes.

Once, when I was very young, Mum and Dad took me to a symphony concert at the Royal Albert Hall. The first half consisted of the usual classics, but the second ended with a contemporary piano concerto. My parents suggested we quietly leave before the concerto, as they feared the modern music would be hard going and were worried I would get bored and start fidgeting. To their astonishment, I didn’t want to leave and listened, spellbound, to the whole piece. I think that was when they realised I might have some musical talent. I wish I could remember what that music was. It may have been a piano concerto by Béla Bartók, later to become my favourite composer. Whatever it was, I found the modern harmonies and rhythms fascinating.

A violin was acquired from the school and I started lessons. I really wanted to play the instrument, but I found it tough. In the early stages, the violin can make the most hideous noises. Nevertheless I persevered and even sat in the violin section of the school orchestra on one occasion. I also remember struggling with a simple string quartet when one of the masters invited some boys to his house for a musical evening. Nicknamed ‘Gobbo’ because he spat when he talked, he had been at Kingston Grammar since my brother was there. He had a slight limp but he could outrun any boy in the school and, when he got angry, he could hit your ear with a piece of chalk from thirty paces. He never missed and the chalk would fly at you so damned quick, you could never get out of the way in time! Unfortunately the violin idea, like the piano lessons, died a natural death, even though I always retained my love of the violin and for the sound of strings in general.

At school, problems started to appear when I had to decide whether to enter the third year in the arts or the science streams. Although I ended up as a musician, my interest then was more towards science but, because my brother had taken the arts route, I tried to do the same. This was a very bad move. It meant taking Greek and dropping chemistry and physics. I already hated Latin and things were not helped by the fact that the Latin master, Mr McIvor, was a nasty bit of work who also became our Greek master. He could have been an even bigger threat to me as he also taught the so-called music lessons. Actually these were simply choral singing classes and as I had a good ear, he didn’t pick on me much, although he gave no real encouragement either. Boring as they were, those periods at least gave me some basic experience in reading music and using my ears. He left me alone in the music periods because he had ample opportunity to vent his spleen on me in the dreaded Greek classes. Boy, did he ever make up for it then! My total lack of interest in or understanding of Greek or Latin gave him plenty of opportunity to humiliate and terrorise me. It was so bad that in just one term I dropped ten or more places in the class and everyone realised that placing me in the arts stream had been a big mistake. I was quickly switched to the science curriculum but the loss of a whole term meant I had to catch up in physics and chemistry.

Actually I found this fairly easy. Science fascinated me, especially anything to do with aeroplanes. I was getting more and more interested in aerodynamics. But Mr McIvor got his own back on me for leaving his Greek classes by making the Latin lessons even more hellish than before. I started lying awake at nights, dreading the next day’s Latin period. I struggled on for a year or so but I began to hate school and lost interest in the subjects I had to study.

By my second year I had become very keen on athletics and cricket, but two things put an end to all that. When the annual school athletics championships were held, I realised that, unlike all my friends in the same year, I was a couple of months older than the maximum qualifying age. The teacher told me not to worry and to enter with the rest of my classmates. The day of the competition came and I not only won four athletics events, running the winning last leg of the relay, but also broke the school 100 yards and long jump records for my age group. Suddenly I was a hero, but then came shame and disappointment. A few weeks later, a teacher came into the class and pulled me to one side. He was very embarrassed as he told me someone had lodged a complaint about my ‘false’ entrance qualifications. I was to be disqualified and all my medals taken away! They admitted a terrible mistake had been made and tried to mollify me with a gift of my choice to make amends. I chose an expensive set of Exacto modelling tools for my hobby, which was aeromodelling, so at least I got something out of the bastards. I covered my embarrassment as best I could and my classmates were very supportive but the episode left a bitter taste. Not only had I trained hard to win those events and lost my trophies, but I felt a cheat, even though it was not my fault.

I turned my energy to cricket practice. I was a natural fast bowler, although my batting was barely adequate. I was chosen for the school under-13 team and at my first ever match I annihilated the opposing batsmen, taking 9 wickets for just 28 runs. Honour was restored. I became a hero again and was assured this would win me my school colours. These allowed you to wear a special tie as a badge of honour and were only awarded for outstanding achievement. Monday assembly came and the headmaster called my name and praised my achievement. But, to my absolute disgust and that of my classmates, he decided I was too young to receive my colours! This double whammy was the last straw. With my declining interest in study and my rapid descent down the end-of-term class placing, I was heading towards a big crisis. I was almost bottom of the class now and terrified of being demoted into the ‘B’ stream, among the rougher kids and away from the friends I had made. I didn’t know who to turn to or what to do, but I wanted out. At the end of that term in my fifth year I was determined to quit school and concentrate on my real interest, aerodynamics.

The first person I turned to for advice was a fellow-aeromodeller, Jack North. I had been making and flying models since I was about seven but it wasn’t until I joined a proper club that I started to make real progress, designing machines and flying them in competitions. At Epsom Downs racecourse, to this day a well-known model flying site, I met some of our best flyers and they taught me how to become a serious competition flyer. I joined the Surbiton Model Aero Club and met my heroes, Pete Buskel and Mike Gaster, both of whom regularly represented Britain in the World Championships. Gaster finally became a world champion himself and went on to an illustrious career as a professor of theoretical aerodynamics. I later switched to the Croydon and DMAC, which is where I met Jack North, a top boffin at the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington who was heavily involved in the cutting edge of trans-, super- and hyper-sonic aerodynamic research. Jack went on to achieve international fame and recognition. A rather dour and intimidating man who didn’t suffer fools gladly, he became a mentor and father-figure to me. In fact, at the age of fifteen, I was privy to some of the very latest theory and developments in this new field of research. Quite something for a teenage kid! Jack was famous for his pioneering work on colour schlieren photography, the technique that made it possible for the first time to observe and photograph supersonic shock waves in the wind tunnel. At the time, the National Physical Laboratory had some of the world’s leading facilities, including revolutionary new shock tunnels. In these, controlled explosions created for a very brief duration air velocities approaching Mach 15 or more. High speed photography made it possible to analyse the airflow over the wind tunnel models at speeds in excess of 15,000 mph. Jack drummed into me the need for complete scientific rigour, a lesson that stayed with me for life. About thirty years later I bumped into him at a Duke Ellington concert and discovered to my amazement he was a lifelong jazz fan. I was always a little in awe of him, but he saw talent in me and took me under his wing. In many ways he had a quiet but profound and positive influence on my life.

When I explained to him that I wanted to get into aerodynamics, he told me what I needed at that stage was just Ordinary level GCEs in Maths, Physics, English and one other subject. He recommended adding technical drawing, something not covered in the school curriculum. In those days, if you were a talented aeromodeller, the hands-on skill you acquired from successfully designing and flying models counted for a great deal; when it came to getting a job, that was worth almost as much as academic qualifications, vital as they were. My hope was that, after getting my ‘O’ levels, Jack could maybe help get me an apprenticeship at the National Physical Laboratory while I continued my studies at night school.

I told my parents about Jack’s advice and how depressed I was at school. They could see I was going through a bad time and contacted the school. The upshot was that I visited the school psychiatrist, who decided I was suffering a mini nervous breakdown and was not in any state to continue my studies. He advised that I should leave school for a while and arranged for me to have free private tuition in the four subjects I wanted. For the next few months I studied hard at home for my ‘O’ levels. To everyone’s great relief I passed with quite good marks in all four subjects. Things did not turn out the way I had planned, however, and a great change of direction was just around the corner.

Although my father let me leave school, he was not pleased and told me that if I quit now, it would have a permanent bad effect. I would find myself always quitting when the going got tough. Leaving school was a big decision to make at fifteen, especially as I knew there was a lot of truth in what he said. Things were compounded by a serious problem with my brother. Teddy was now a high ranking civil servant in Malaya. When he heard about my plan to leave school early, he was very angry and wrote to my father. In turn I was furious with my brother and wrote a long letter back, castigating him for making judgments about my life, when he was six thousand miles away and had no idea what I was going through. I also made nasty, unwarranted remarks about his wife Mary, who shared his view of the situation. I blamed him for my having spent my life trying to live up to his example and said it was his fault I had been pushed into the arts stream and that this was the cause of much of the problem. In reply to my outburst he demanded that I apologise to his wife, which I did reluctantly.

I had never been close to him, partly due to our age difference and partly because he was always away from home, at university or in some distant country. I had admired him from a distance and always got excited when he came home for a few days. Now, as far as I was concerned, he could stay in Malaya forever. Our rift mended after a while, but it was only a couple of years before he died that I finally shook off a constant need somehow to prove myself to him. It had been probably one of the strongest motivating forces in my life. Teddy retired to Malta and it was only when he belatedly started using email that I got really close to him. During his last two years on this earth I poured out my soul to him and he reciprocated, telling me, for the first time, how very proud of me he had been all along and how much he had grown to respect my talent as a musician. He even began collecting jazz records and sought my advice on what to listen to. It was a very moving time for both of us and I was terribly upset when he died suddenly of a heart attack.

While studying for my ‘O’ levels I rediscovered music, but this time it was not just another passing fad. I acquired my first record player and rented a radio. My first passion was for Elvis Presley. I bought his hit, ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, I read about his fame, his pink suits and his pink Cadillac and was deeply impressed with his glamorous and rebellious image. I started trying to imitate him, even calling up a record company in the hopes of getting ‘discovered’. My hopes were dashed when they told me I needed to send in a tape. I didn’t own a tape recorder and knew no musicians, so I quickly realised that being a pop star was a stupid adolescent dream. For years after that I kept my early infatuation for Elvis to myself and was very embarrassed about it. It wasn’t until much later that I realised it wasn’t such a bad thing after all. Listening to those early Presley tracks now, I realise they introduced me to a watered down ‘white’ version of the blues, a musical form I became steeped in for ever.

I would listen to my radio, turned down very quiet, under the bed clothes at night and soon tuned into Willis Conover’s Jazz Hour, that wonderful nightly programme on American Forces Network. At 11 p.m. there would be an hour of good quality music by Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee and all the top singers. This was followed by Jazz Hour, which was a total revelation to me. For the first time, I heard the whole panoply of jazz, from Louis Armstrong to Charlie Parker. I was hooked and my interest in science and aeronautics began to fade. I started to absorb all the new sounds and read anything I could find about jazz. Unfortunately I also learned too much about the destructive lifestyles of people like Parker and Billie Holiday. In my impressionable teens, I became infatuated with the image of black musicians producing wonderful music whilst fighting racial prejudice and often resorting to hard drugs to alleviate their suffering. The whole package had a fatal attraction for someone who, having failed to gain academic qualifications, was looking to rebel against his family’s aspirations. My new passion would later lead me into the lower depths of the human condition but, thanks to my determination to excel as a jazz musician, it would also enable me to find my true calling.

The origins of my struggle with drug addiction probably began during this period. I became more and more aware of certain debilitating physical and mental symptoms and began to search for some kind of relief. I felt unable to cope with those perfectly normal feelings of unease that most people seem to take in their stride. Maybe the emotional problems I had suffered throughout my childhood were exacerbated during adolescence, but I felt as if I was lacking some of the normal physical and mental defence mechanisms that enable most people to cope with adult life. Our family doctor prescribed heavy barbiturates to my mother to help her insomnia so, even while still at school, I turned to him for help with my anxiety and depression, hoping for some kind of chemical relief. He was a Scot and had a typically humane approach – the kind of doctor you could always talk to. At first he gave me a mild sedative, which helped my anxiety to some extent but tended to make me even more depressed. After a while he tried me on Drinamyl, a combination of Dexedrine and phenol barbitone, often prescribed back then to relieve depression or to help lose weight. Dexedrine is a powerful stimulant and it helped my depression so much that I was soon asking for more. The doctor did his best to regulate my consumption.

There was one good bit of news though. I found I was to miss military service. Conscription was abandoned just a couple of months before I reached the call-up age. For once my age proved to be an advantage. Mind you, I had quite enjoyed the two years I was in the army and then the air cadet force at school. The idea had been to do basic training there but I think the military would have put us through it all again on call-up. I did get my lance corporal’s stripe after the first year, and if I ever need it I still remember how to strip down, clean, oil and reassemble a Lee Enfield .303 rifle, a wonderful old piece of kit that was still standard issue. Dad had one just the same, back in World War One. I even fired a Lee Enfield once, but it was fitted with a smaller caliber 0.22 inch barrel. They told us the kick of a 0.303 would have been too strong for a fourteen-year-old. If I had stayed at school, I could have learnt to fly in the cadet force eventually. I still had a hankering to be a Spitfire pilot, but it was not to be.

At first I developed my passion for jazz in tandem with my love of aviation. I still vaguely wanted to become an aerodynamicist but gradually music gained the upper hand. However, it wasn’t until I happened to see a film, The Benny Goodman Story, that I made the decision to become a professional musician. The movie was a typically bastardised Hollywood biopic, but at the time it had a profound effect on me. I loved the brash excitement of Harry James’ trumpet which I had heard on my sister’s records and which was heavily featured in the film. When I got home from the cinema, I was determined to play the trumpet, like James. Something odd happened while I was asleep, though, because when I woke the following morning all I could think about was Benny Goodman’s clarinet playing. This badly-made movie was a kind of ‘revelation on the road to Damascus’. It was not just the music but the lifestyle and the heroic struggles for recognition of the professional musician that captured my imagination. I had always believed that, for something I was really interested in, I had the capacity for hard work and attention to detail. Jack North had instilled in me the importance of application and scientific rigour. That lesson stood me in good stead when I applied it to music. That was it: I would be a professional jazz clarinet player, shit or bust, and would transfer all my enthusiasm and dedication from aerodynamics into playing jazz. At last, I seemed to have found my vocation in life.

2

‘Pete, will you play at the opening of my new club?’

Ronnie Scott

Having decided to play the clarinet, how was I going to start? My parents were only just reconciled to the fact I wanted to study to be an aerodynamicist, although I think they had serious doubts about how I was going to achieve this. After having paid for piano and then violin lessons, all to no avail, they were hardly going to pay for a clarinet and more lessons to satisfy what they considered another passing craze. I knew I had to do this with no help, at least until I could prove I had some chance of making a success at my new vocation. I started to look for jazz records and an old friend from prep school, John Callinan, who also shared my early interest in model aeroplanes, obtained some old 78s from his sister. He would bring her record player over and we would listen to the few jazz records in her collection. The one that I remember best was a Louis Armstrong All Stars live concert with Edmond Hall on clarinet. Hall made a big impression on me and I began learning his and everyone else’s solos, by ear. Most of my spare time was now spent soaking up everything I could about jazz. I learned every note from each new record I got my hands on and would lie in bed at night humming improvised solos under my breath and imagining I was playing onstage. Not just clarinet solos but all the other instruments as well. I would pretend I was playing a real concert and visualise every aspect of the performance, down to the announcements and the applause. In fact without realising it I must have been using a ‘visualisation’ technique similar to that used today by modern sportsmen and women.

One often hears references to this psychological method, but very little about what it means in practice. There is a lot more to it than visualising yourself winning Wimbledon or an Olympic medal. Sure, you have to ‘see’ yourself at the winning moment, but that gives no idea of the whole method. It’s an extremely difficult and exact discipline that involves visualising (with all five senses) every minute detail of the task ahead.