Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

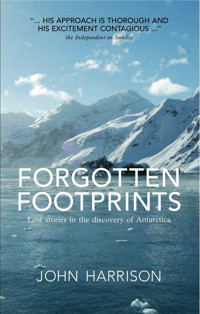

Forgotten Footsteps won Creative Non-Fiction Wales Book of the Year 2013. Following Wales' Book of the Year Award 2011 winning Cloud Road, comes Forgotten Footprints, a history of the Antarctic Peninsula, South Shetland Islands and the Weddell Sea, the most visited places in Antarctica. In 12 years John has visited over 40 times and guides and lectures on adventure cruise ships. He delivers a selection of highly readable accounts of the merchantmen, navy men, sealers, whalers, and aviators who, with scientists and adventurers drew the first ghostly maps of the white continent.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 571

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Forgotten Footprints

Lost Stories in the Discovery of Antarctica

John Harrison

For Celia, who found me there

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE:

1: The Master Craftsman:

2: William Who?

3: The Admiral and the Boy Captain:

4: Charted in Blood:

5: The Circumnavigators:

6: Deception Island

7: The First Antarctic Night 1897–99:

8: A Permanent Foothold:

9: The Great Escape

10: Antarctica with a Butler:

11: Red Water: Whaling

12: The Boss: Ernest Shackleton (1877–1922)

13: Living in Antarctica: The Bases

14: Who Owns Antarctica?

15: The Future of Antarctica

A Glossary of Specialist Polar and Maritime Words

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Who is this book for?

The history of Antarctica is largely written in magisterial biographies and coffee-table tomes that require three polar heroes to lift them. My own collection can swiftly be piled up into a fortress against the harshest blizzard. Some of the explorers are household names, bywords for bravery and suffering. But none of those heroes discovered Antarctica: neither Cook, Scott, Shackleton nor Amundsen. You would think it was a conspiracy. The Russians will tell you Admiral Bellingshausen discovered it, Americans make a claim for a sealing captain called Nathaniel Palmer. No.

It was a Briton no one has heard of. This book tells his tale and those of the other jobbing sailors who were the first to find Antarctica, and to start to chart its shape. There’s a few heroes too, where they went to places we can visit. That is the second aim of the book: to describe the discovery and exploration of Antarctica through the places that feature in the visits of the cruise ships which now land over thirty thousand passengers a year on the last continent. It focuses on the Antarctic Peninsula down to the Antarctic Circle, the South Shetland Islands, and the fringe of the Weddell Sea; around 98% of tourists come here. There are some fine general histories but they give equal weight to expeditions and activities which took place on remote shores and in harsh interiors visited only by a handful of professional scientists and daring adventurers. This book gives the background to the things and places visitors actually see. Whether you are planning a trip, or you are just an armchair adventurer it will explain how mankind found the last continent and how we have treated it.

PROLOGUE:

The Ghosts of Detaille Island

I did not want to go ashore. We had never been asked to start an Antarctic landing at midnight. I’d get no sleep before and very little after. The Expedition Leader was showboating for the guests, perhaps because they included a Belgian Prince and Baron von Gerlache, the grandson of the Belgian explorer Adrien. Another guest owned tankers, six hundred of them. At Ushuaia, the Argentine gateway to Antarctica, their entourage brought the airport to a halt, as the authorities tried to find parking places for their fifteen private jets.

I climbed into my Zodiac, a five-metre-long open inflatable powerboat, and was lowered into the bay to ferry ashore the descendants of Adrien de Gerlache and their friends. The guests had spent the evening partying and celebrating their farthest south, just below the Antarctic Circle. We landed on a tiny block of rock on which stood the old British Detaille Base, and explored the huts by torchlight. The season was advanced and night had returned. The days had become mortal again; they had a beginning and an end.

Detaille Base seemed more authentic in the torchlight, and I enjoyed picking my way round. In its few years of active life from 1956 to 1959, it was lit by fitful generators and hot-handled hurricane lamps. It was a time capsule from my childhood. On a table lay the August 1953 edition of World Sports magazine. The middle-distance runner Christopher Chataway was on the cover, breasting the tape in a number 1 shirt. He was one of the athletes who would, the following spring, help Roger Bannister to run the first four-minute mile. Cupboard doors opened on tins whose primary-coloured fifties’ cheerfulness was corroded by rust along the joints: the war was over, custard and porridge for all. The party enjoyed their visit; their boisterousness subsided to pleasant thoughtfulness. The Prince took off his mink-lined hat and absent-mindedly stroked the fur with his thumb. They left in trickles; I ran shuttles ferrying them back across the bay.

Each time I returned to the ship the bar sounds from the lounge high above the stern were more raucous. Each shore visit was more tranquil. The Expedition Leader asked if any of the Zodiac drivers wanted to be lifted. I said I was fine. I drove the last passengers back at 03:30, leaving the empty base to its ghosts, dropping the other staff at the gangway, before pulling away to prepare the Zodiac to be lifted by crane onto the top of the rear deck. I unfolded the web of three pairs of straps, coming to a central ring, then clipped the hooks onto the shackles at the front and centre of the boat. The back ones are fixed. I stowed my backpack where it would not tangle with them when I hitched the ring to the hook. Snug in my one-piece survival suit, I balanced, on my back, on the side pontoon of the boat. Above me, in the black blanket of sky, rents worked open, and the cover began to break up. Haphazard stars appeared. The radio crackled: ‘John, we have slight problem with anchor.’ When Polish officers speak English the articles disappear. ‘Stand by fifteen minutes.’

She was an old Swedish ice-breaker built for coastal patrol, launched as the Njord, the god of the sea, but renamed the Polar Star. She does not go to Antarctica now. Under the delightful Captain Jacek Mayer, who taught me to use a sextant, and whose first command was a square rigger (‘She is in a museum now, I am still sailing.’), she hit an uncharted rock off Detaille Base in 2011 and ripped her belly open. The company went bust as she sat in a Canaries dockyard and the repair bill mounted.

Now I had turned off the 60 HP Yamaha outboard engine, I could hear the fans and motors which keep the ship alive, the tinkling party, and the Filipino sailors I had worked with for six years, Alan, Lito and Dallas, calling to each other tiredly in Tagalog. The water cooling my engine piddled into the sea. I felt the wavelets ping the rubber hull. I saw the stars brighten and then fog in the confusion of the cloudless sweep of the Milky Way: the edge of the galaxy opening up with light from times when men walked in animal skins. The ship was a solitary pool of warmth and light. I let my Zodiac drift away from her into the darkness at the edge of the bay. Her deck lights were a cluster in the sky, a constellation without a name: a new, unpredictable star sign. The bar music faded and all I could hear was the creases of ocean slipping under the boat, the cold air hosing through my throat, and the thump of my heart. The Zodiac turned slowly as she drifted, and I was the only soul alone in an empty world. The only man abroad in a continent. The last continent. But who discovered it? I didn’t care. I was unspeakably happy.

1

The Master Craftsman:

James Cook (1728–1779)

VOYAGE I (1768–1771) VOYAGE II (1772–1775) VOYAGE III (1776–1779)

A ditch-digger’s son becomes one of the greatest navigators of his own age, or any other age, and is sent out three times to look for the one land he does not believe exists.

In a locked, unlit village shop, the gangly youth eased himself out from under the counter where he had slept the night. He was the son of a farm labourer who had left Scotland when it was reduced to desolation after the crushing of the Jacobite rebellion of 1715–16, and moved to the straggling hamlet of Marton in Yorkshire, in north-east England. Two years later, the labourer’s wife gave birth to a son, James, who at eight years old was already helping his father clean ditches and cut hedges. A reputation for honest muscle earned the father a job as bailiff to the local Lord of the Manor, Thomas Skottowe, at a larger village: Great Ayton. Skottowe saw something in the boy and paid for him to attend school. To his humble parents, apprenticing James to a shopkeeper in the nearby fishing village of Staithes was a way to rise above a life of physical drudgery. But to Cook an apprenticeship to a draper-cum-grocer was just a genteel jail. One day a lady paid for goods with a brilliant silver shilling. When the shop closed, the youth read on it the letters SSC: South Sea Company. He put it in his pocket and replaced it with one of his own. The shopkeeper William Sanderson noticed it missing and accused Cook of theft. Cook’s fervent denials were accepted, but Sanderson’s lack of trust rankled, and Cook’s pocket already held the shiny promise of another world. He asked to be released from the apprenticeship to go to sea. Sanderson agreed and Cook was bound as a seaman apprentice for three years with the Quaker family of John Walker of Whitby, a town famous for its ruined monastery, its whaling, and, for me, as the port where Dracula enters England.

The Walkers gave James a room of his own and paid his fees to attend sea school in the town. At this time London’s hearths and furnaces devoured over a million tons of coal a year, much of it supplied by north-east England in a thousand sturdy, blunt-bowed colliers known as cats, carrying six hundred tons of coal. He first sailed in February 1747, aged eighteen, becoming a Master Mate in 1755, when he was offered his own command: the Friendship. But Cook’s ambition had been shaped by reading the accounts of the great explorers of the Pacific. War with France was looming and he might be pressed into the Navy. With great courage he decided to meet fate on his own terms. He turned down promotion to a merchant captain and signed on as an Able Seaman in the Royal Navy. The Navy was so short of experienced men that Cook made First Mate in less than a month. He learned surveying during the successful war to break French rule in Quebec, and after the war he was tasked with surveying the islands off Newfoundland which the peace treaty had ceded to France. A century later Admiral Wharton said of Cook’s charts ‘their accuracy is truly astonishing.’

In Cook’s day, the supposed southern continent Terra Australis Incognita, lying in temperate latitudes and ripe for exploitation, was an idea that would not die. Cook doubted its existence long before he ever sailed south. The man described as ‘one of the greatest navigators our nation or any other nation ever had’ spent much of the rest of his life looking for something he doubted existed, but proving that conviction would re-write the map of the world and make him immortal. The Antarctic passages of his voyages would be forceful expeditions pressing as far south as was humanly possible, but he did so in a period of history when the earth was suffering a miniature Ice Age and it was the worst time in two centuries to be doing it.

The first problem he faced was the envy of a rival: Alexander Dalrymple. He was the creature of the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, the man who had so frustrated clockmaker John Harrison, the genius who solved the longitude problem. Maskelyne recommended that the expedition should be led by Dalrymple, a scientist and East Indiaman captain who was later the first Chief Hydrographer; he was also vain, cussed, and a man with a genius for backing the wrong horse. He was convinced his career would be crowned by charting the Terra Australis Incognita, which his readings of old and often dubious charts and memoirs convinced him was a known fact.

Dalrymple shot himself in the foot by demanding absolute overall control of the expedition. The Navy had made one famous exception to the rule that the senior Naval officer was the overall commander. The first Astronomer Royal, Sir Edmund Halley, had been given absolute control to observe a transit of Venus in the Pacific. Chaos ensued and mutiny threatened. Halley was Maskelyne’s immediate predecessor as Astronomer Royal, so it was idiotic to imagine the lesson had been forgotten. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir Edward Hawke, made his oppositions plain enough even for Dalrymple, declaring ‘I would rather cut off my right hand than sign such a commission.’

Cook shared his cabin with the naturalist, the twenty-five-year-old son of a rich, land-owning agricultural improver who had made a fortune draining the marshy fenlands of east England: a man who had employed numberless ditch-diggers and labourers like Cook and his father without ever knowing their names. Young Joseph Banks owned an estate near Lincoln worth £6000 per annum. He could have bought both the expedition ships out of a year’s income and still have had cash spare to live like a gentleman. At Eton College, bored with Greek and Latin, he walked home from a swim in the river through a flower meadow and decided to study the beautiful flora. Oxford had no botanist, so he paid for one to move there from Cambridge. The whim became a stellar career. Once on board he impressed Cook with his diligence. Nothing was beneath his attention. He even noted that the weevils in the ship’s biscuits were three species of the genus Tenebrios and one of Ptinus, but the white Deal biscuit was favoured by Phalangium cancroides.

The orders governing the expedition read comically today, governing as they do transactions with people and places which often did not exist; it is the bureaucracy of Never Never Land. If Cook found Antarctica, he had to take possession ‘with the consent of the natives.’

For a ship, he chose a Whitby cat, renamed the Endeavour. The cruise took them to the main island of Tierra del Fuego where Banks showed his disdain for superstition by shooting a wandering albatross. Despite this, the Horn was a millpond. They sailed for the heat of Tahiti where the astronomers would observe the transit of Venus across the face of the sun, a rare and irregular event that allows accurate calculations to be made of the distance from the earth to the sun. Their next orders were to go to 40° south, heading into the south-west sector of the Pacific. To appreciate how good Cook’s gut instincts were about Terra Australis Incognita, you have to look at the diaries of the other officers on his two ships to see how long, and how longingly, they clung to the romance of a temperate continent. Every time they go ashore in New Zealand, Banks refers to it as a visit to the continent. He calls his party of believers ‘the Continents’ but refrains from calling the opposition the Incontinents. They all but circumnavigate the North Island, but the officers refuse to accept it is an island until Cook goes back north to Cape Turnagain where he had begun. Although the weather was poor for much of the time, making surveying difficult, when the explorer Julien Marie de Crozet, a fine navigator himself, sailed these waters with a Cook chart he ‘found it of an exactitude beyond all powers of expression.’

When Cook reached home he had been 1074 days away from his wife Elizabeth, whom he had left pregnant and with young children. But he first visited the Admiralty, before going home to find their baby had been born and died, and another child was also dead. Within one month he was preparing to leave on a circumpolar trip. There were still southern latitudes where Terra Australis Incognita might have been skulking since the Flood. Cook didn’t believe it was there but he reasonably conceded that there were latitudes to the west of Cape Horn so little visited that sizeable land masses could have been missed.

Cook made two more Whitby cats famous: the Resolution, 462 tons, with 118 men, accompanied by the Adventure, 336 tons, with 82 men under Captain Tobias Furneaux. There were names already famous on board, and famous names to be. The Able Seamen included George Vancouver, aged fifteen, later to explore the Pacific NW Coast. AS Alex Hood, aged fourteen, was cousin to two admirals: Hood and Lord Bridport. Dalrymple didn’t even make the long-list, but he had been busy redrawing the world from his desk. While Cook was away he had published a new chart of the southern oceans showing the extent of Terra Australis Incognita, incorporating the few sightings of land which could be given any credence, such as the French navigator Lozier Bouvet’s claim to have seen a snowy headland on the first day of 1739 and named it Cape Circumcision. Dalrymple’s chart was shoddy work, based on a map by Abraham Ortelius: a masterpiece in its day, but now nearly two hundred years old. In his early thirties, Dalrymple was already a young fogey.

Their best chronometer was justifiably famous: K2, the commercial rebuild of the John Harrison masterpiece H4 that won him the £20,000 prize for solving the longitude problem. Its error was less than one second a day. One of the scientists was Johann Reinhold Forster, a fan of Dalrymple and an overpaid complainer with the sharp hunger for recognition and respect which only the truly insecure display. But his son Georg was altogether better company. The handsome Banks was missing; grown vain while he was the toast of London society, especially its women. He sulked about the choice of small ships again, and flounced off to botanise in Iceland. Cook’s expedition would make four passes south and come within half a days’ sailing of seeing Antarctica, never, of course, knowing it.

In Cape Town, they heard the sea gossip. The Breton noble Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen-Trémarec with two French ships had recently put into harbour, with orders similar to Cook’s to hunt for the southern continent. They had returned from the seas where Cook was heading, and claimed to have discovered land at 48°S, and coasted along it for 180 miles. They had seen a bay in which they hoped to anchor but when their boats were sent in to sound for an anchorage, a gale blew up and the ships stood off, abandoning the men ashore. Cook’s lieutenant Charles Clerke fumed that there existed no circumstance so bad that Kerguelen had to abandon his men. Clerke was a man whose candid diaries make you long to have worked with him. He comes across as witty, earthy, pragmatic and humane. One officer summed him up like this: ‘Clerke is a right good officer, at drinking and whoring he is as good as the best of them.’ Cook was too preoccupied wondering whether the French had stolen a march on him to criticise their personnel policies. Kerguelen, despite the distance between him and the shore, was sure it was a land of plenty. The motto of believers in the southern continent was Often Wrong: Never in Doubt.

On 22 November 1772, Cook headed for Bouvet’s Cape Circumcision. Bouvet claimed to have sailed for twelve hundred miles along a shore covered in snow and ice but with land beneath. His pilot thought it was nothing of the sort, but fools make work for wise men. By late November Cook began to see icebergs. Nothing prepares you for your first sight of large icebergs. In dull light the turquoise blue shines out brilliantly. They can look as if violet lamps have been lit in the recesses. The largest I have ever seen took three hours to steam past; it was twenty-nine miles long (forty-six kilometres) but was only a broken fragment of a much larger one. In mid-December Charles Clerke reported horrible fogs ‘so thick we can scarcely see the length of the quarterdeck’ and out of the murk came bergs which towered over the ship. He reported one as big as St Paul’s Cathedral. Even the taciturn Cook took a moment in his diary to appreciate the grandeur of seas so fierce they broke over the tallest icebergs, but his responsibilities soon resumed precedence over aesthetics: the scene ‘for a few moments is pleasing to the eye, but when one reflects on the danger this occasions, the mind is filled with horror, for was a ship to get against the weather side of one of these islands when the sea runs high she would be dashed to pieces in a moment.’

It would soon be midsummer, but the weather was getting worse. Ice smothered the rigging; a rope as thick as two fingers became as broad as your wrist and would not run through blocks and pulleys, so sails and yards could not be moved. Men were continuously employed hacking off ice, and clearing it from deck. If they did not keep pace, the weight aloft would capsize the ship. At least most of the livestock died and everyone enjoyed fresh meat.

By 13 December they were at 54°S, the latitude where Bouvet saw his coast, but the weather had driven them 354 miles east of his location for Cape Circumcision, so Cook tried to force his way south, into the pack. He tried for four weeks before the weather eased on 15 January and he enjoyed gentle breezes and serene weather for five consecutive days. Fresh water was a problem; in Antarctica most of it is frozen. He expected most of the sea ice would be saltwater, but tested it by bringing brash ice on board in rope slings and baskets and melting it. All the ice was fresh water. In two days they made more water than they had taken on at Cape Town. The wittiest account comes from an Irish gunner’s mate called John Marra who concealed his journal from the enforced collection at the end of the voyage. ‘I believe [this] is the first instance of drawing fresh water out of the ocean in hand baskets.’ The reason is that when seawater freezes, the salts do not freeze with it, so freezing purifies water just as boiling does. By killing seals and birds, they could be self-sufficient in the south: vital if extensive voyages were to be conducted so far from known land. Cook was the first to prove this could be done.

His perseverance was rewarded when they pressed south once more and punched their way through the pack. At noon on 17 January, at around 40°E he wrote ‘we were by observation four and a half miles south of [the Antarctic Circle] and are undoubtedly the first and only ship that ever crossed that line’ – which must have raised eyebrows over on the Adventure. The next day thirty-eight icebergs could be seen from the masthead and later in the day at 67°15´S a wall of ice barred their path. He was blocked seventy-five miles from the continent.

There was still a Breton bubble to puncture. In good seas they cruised for a week with remarkable ease right across the land seen by Kerguelen the previous year. Charles Clerke relished it. ‘If my friend Monsieur found any land, he’s been confoundedly out in the latitudes and longitudes of it for we’ve searched the spot he represented it in and its environs too pretty narrowly and the devil of an inch of land is there.’

They headed east but on 8 February the two ships were separated in fog and forced to abandon searching for each other, and head for their agreed rendezvous in Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand. Captain Furneaux in the Adventure used the separation to head rapidly north and hightail it directly to New Zealand. Cook used it to push south once again, this time lacking a support vessel to come to his aid, but there are hints that Cook feels safer without Furneaux’s assistance. On 10 February he was passing south through 50° of latitude when they saw many penguins in the water, raising hopes of land. A week later they were treated to shows of the aurora australis. Later in the month they suffered a gale which brought sleet and snow. It’s the most miserable mix of all; few garments are warm when wet. The night had enough light for them to see huge icebergs all around and pray for daylight, but when it came they were even more scared as it spelled out just how dangerous their position was. One four times the size of the ship exploded into four pieces just as they were passing.

Forster Senior whined about the ‘whole voyage being a series of hardships such as had never before been experienced by mortal man.’ The rest reacted in the ambivalent way that typifies most first impressions of Antarctica: awe, fear and beauty.

Cook surveyed his men, and found their bodies and clothing were damaged and worn. Among the meagre livestock left on board the poor sow chose this time to farrow nine piglets. Despite efforts to help her care for them, all were dead by the end of the same afternoon. They sailed north to New Zealand, and found the Adventure had been and gone, but not before a shore party seeking water and greens had been killed by Maoris. Their cooked remains were later found in parts, in a basket. Not even this could prevent Cook being even-handed about the Maoris: ‘Notwithstanding they are cannibals, they are naturally of a good disposition.’ They stayed in warmer climes all winter but in the spring, on 25 November 1773, Cook turned the bow south again. On 12 December the first iceberg welcomed them back to the ice-realm. Soon ice jammed the blocks again and icicles an inch long were on each deckhand’s nose. They crossed the Antarctic Circle a second time but were again soon blocked. On Christmas Day the crew stupefied themselves on hoarded brandy. Cook headed north east a while then turned back south on 11 January 1774, to make his third crossing of Antarctic Circle. They were desperate for land, willing it into view. Cook recorded that he ‘saw an appearance of land to the east and south-east’ and Wales: ‘a remarkably strong appearance of land.’ Next day Clerke soberly reassessed these hopes: ‘We were convinced to our sorrow that our land was nothing more than a deception.’ When the atmosphere lies in layers of differing densities it bends light back to earth showing images of land hundreds of miles away. At the end of the month they drove farther south than ever, reaching 71°10’ S, 235 nautical miles beyond their previous best, though in this longitude, they were actually farther from the coast.

‘We perceived the clouds over the horizon to the south to be of an unusual snow white brightness which we knew announced our approach to field ice. … It was indeed my opinion as well as the opinion of most on board, that this ice extended quite to the Pole or perhaps joins to some land to which it has been fixed from the creation. As we drew near this ice some penguins were heard but none seen and but few other birds or any other living thing to induce us to think any land was near.’ This may have been the poignant sound of penguins in water, where some species vocalise in a way they never do ashore, crying like a man lost.

He was ‘now well satisfied no Continent was to be found in this ocean but what must lie so far to the south as to be wholly inaccessible for ice.’ They headed for the warmth of Easter Island. Cook went down with a stomach illness. Perhaps it never left him, because his personality underwent a sea change, witnessed but not understood by all around him. The diary of one young officer, Trevenen, calls him a tyrant. They next headed west for Tierra del Fuego, reaching there just before Christmas, naming a dramatic double-turreted rock York Minster, after the great cathedral of Cook’s native Yorkshire. The island they discovered on the 25th became Christmas Island. On Christmas Eve they shot six geese for Christmas dinner and Marine Bill Wedgeborough celebrated the birth of Christ with such fervour that he went forward at midnight to relieve himself and was never seen again.

They did some charting but it was half-hearted by Cook’s standards, not even discerning that Cape Horn, whose whereabouts it was always nice to be sure of, was on an island. The men yearned to set course for home, but Cook turned south-east to explore the missing piece in the jigsaw of the Southern Ocean: the seas below and between Cape Horn and the Cape of Good Hope. This was the sector where Dalrymple, unknown to Cook at this point, had been publishing charts of the lands to be seen there. By 6 January they were sailing through the land Dalrymple had drawn around the mythical Gulf of St Sebastian. Cook sailed north to the place Dalrymple had argued was the peninsula marking the north-east limit of the gulf. This assignation had better provenance: a merchant, English despite his name, Antoine de la Roche, had seen land here in a storm exactly one hundred years before in 1675. Arriving at la Roche’s co-ordinates he had taken, Cook found only fog. It cleared next day to reveal an iceberg, which in the mild latitude of 54°S suggested high and cold land was close by. It was first seen by Midshipman Willis, who was known for his heavy drinking, and possibly only on deck to relieve his bladder. The off-lying island he saw is named for him and soon there was more, a long run of coast, with high icy mountains towering into the clouds, separated by steep glaciers. Cook wrote: ‘Not a tree or shrub was to be seen, no not even enough to make a toothpick. I landed in three different places and took possession of the country in his Majesty’s name under a discharge of small arms.’ They sailed down the dramatic north-east coast, Clerke discerning subtle variations in misery and desolation when comparing it to other Godforsaken places they had seen and concluding ‘I think it exceeds in wretchedness both Tierra del Fuego and Staten Land (Island), which places till I saw this I thought might vie with any of the works of providence.’ He didn’t appreciate the ‘sublime’ nature of wild landscapes; that would become popular taste in the next century.

But as they went south-east and the shore continued, mile after mile, for a hundred miles, some of the men began to believe this was at last the ancient dream: Terra Australis Incognita. Then the coast began to turn; there were off-lying islands separated by reefs and rocky shoals which catch tabular icebergs blown north. The fjord now named Drygalski opened up, then a string of islands and rocks forced them further out and when they could come close again they saw the land running back north-west, the way they had come; it was an island. Cook named the southern tip Cape Disappointment, adding. ‘I must confess the disappointment I now met with did not affect me much, for to judge of the bulk by the sample it would not be worth the discovery.’ His sense of tact seemed to be wearing a little thin because he then named it after the King: South Georgia. It is still governed by Britain; it must be, there is a Post Office. Cook turned south-east and spent the first three days of February in conditions that appalled even his most experienced officers. The land they suddenly saw, when they could see at all, threw peaks straight from the sea some four thousand feet into the clouds. Cook was happy to declare it ‘the most horrible coast in the world’ then name it after his friend, the Lord of the Admiralty, the Earl of Sandwich. Unsure of whether they were looking at islands or a peninsula they called it Sandwich Land.

He declared:

I firmly believe that there is a tract of land near the Pole, which is the source of most of the ice which is spread over this vast Southern Ocean. The greater part of this Southern Continent (supposing there is one) must lie within the Polar Circle where the sea is so pestered with ice that the land there is inaccessible. The risk one runs in exploring a coast in these unknown and icy seas, is so very great, that I can be bold to say that no man will ever venture farther than I have done, and that the lands which may lie to the south will never be explored. Thick fogs, snowstorms, intense cold and every other thing that can render navigation dangerous one has to encounter, and these difficulties are greatly heightened by the inexpressibly horrid aspect of the country, a country doomed by nature never once to feel the warmth of the sun’s rays, but to lie forever buried under everlasting snow and ice.

The natural harbours which may be on the coast are in a manner wholly filled up with frozen snow of a vast thickness, but if any should so far be open to admit a ship … she runs a risk of being there forever.

Future travellers would read these words and feel an icicle enter their hearts.

Elizabeth Cook must have been delighted to have one of the most talked about men in the Navy back in her house, when he eventually got there after first visiting the Admiralty. She was also glad to be pregnant within two months, while he made plans to settle in London. He had nothing more to prove. After six months he was invited to a dinner with three of the most powerful men in the Admiralty to advise on the manning of an expedition to find the North West Passage by sailing across the Canadian Arctic to the spices and silks of the east. The prize equalled that for solving longitude, £20,000, much of which would go to the captain. By the end of the evening Cook had risen to his feet with his glass in hand and volunteered to lead it. It was probably just what their Lordships had intended would happen. What Elizabeth thought is another matter. In another six months he was gone. She would live to be ninety-one, but she would never see her James again. She would outlive all her children.

His orders were to take the latest cats, the Resolution and Discovery, to look for the land Kerguelen-Trémarec had claimed in the sub-Antarctic waters, then probe the west coast of North America, loosely claimed as New Albion by the British without actually having visited it. He was to press north into the Arctic through the Bering Straits, then retire to overwinter in Kamchatka, Siberia. In the spring he was to return to the high latitudes and look for the most promising passage to the east. One of his young sailing masters was a highly determined and skilful man called William Bligh.

The Antarctic element of his final expedition was modest. He checked the positions of Crozet and Marion Islands and found the French navigators had located them accurately. At the Kerguelen Islands, despite finding a bottle claiming them for France, they left a Union Jack and a counterclaim. The rest of the trip was spent carrying out orders in a slow and aimless way. It was not the Cook any of them knew. His temperament, once so sober and serious, began to be subject to violent fits of anger, bouts of indecision, and irrational attacks of urgency.

Ironically Cook’s final discovery was Hawaii, where he was revered, arriving exactly how and when ancient myths predicted a God would, but when he was forced back to repair his ship he stepped outside the myth: the god did not return. He was clubbed to death in the surf, cut up and most of him eaten. Just a few remains were returned to a heartbroken Charles Clerke, already dying of tuberculosis at thirty-eight, for burial at sea.

In almost any other decade Cook would have met less ice and discovered Antarctica. He did so by inference; penguins, seals and icebergs all required land. Although he never saw Antarctica, he added much information about what it was not, and made it impossible for anyone of reason and judgement to believe that any large new land mass lay in the southern temperate zone. The area we know as Antarctica contains huge swathes of ocean he first sailed through, peppered with small islands as wild as the day he saw them. He concluded that there was nothing more to be gained by further exploration only because his vision of exploration was bound up with early ideas of empire: the utility of a place was all. He also failed to appreciate that another age would bring other young bloods eager to exceed their predecessors.

The boy who saw a silver world shining in a shilling piece set the gold standard. Yet he didn’t discover the last continent. And if Cook didn’t, who did? Navigators from all nations would follow like sharks behind a great ship, seeking glory. But their discoveries did not lead to conquest and empires, or to riches. The greater share of polar fame has gone to the heroic failures: Franklin, Scott and Shackleton.

Who discovered it in the first place? Who indeed.

THE ANCIENT MARINER

Samuel Taylor Coleridge is often remembered for a cliché of poetic inspiration: he wrote Kubla Khan in an opium-inspired trance. It is a fine tale, but false. The inspiration for his epic poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is much stranger, and is completely true. The albatross of his tale was a real bird, shot in 1726 near Staten Island north-east of Cape Horn. However Coleridge did not begin intending the albatross would be a central motif and it was not even his own idea.

Poems are written for many reasons and his reason was money. He and his friends William and Dorothy Wordsworth were on holiday in the English West Country and finances were failing. On a walk along the coast near the small port of Watchet they hatched a project to publish a book of ballads, a form then bringing popular success to Robert Burns and Thomas Chatterton. Coleridge was turning over his mind a nightmare, dreamed by his friend and local bailiff John Cruickshank, of a spectre-ship that still sailed although all its planks were gone: a skeleton of a ship.

Wordsworth warmed to the idea. ‘I suggested; for example, some crime was to be committed which should bring upon the Old Navigator, as Coleridge after delighted to call him, the spectral persecution. I had been reading Shelvocke’s Voyages, a day or two before, that while doubling Cape Horn, they frequently saw albatrosses in that latitude. Suppose you represent him as having killed one of these birds on entering the South Sea, and that the tutelary spirits of these regions take it upon them to avenge the crime.’ Coleridge seized the idea, and studied the original account. Shelvocke wrote ‘we had not had the sight of one fish of any kind, since we were come to the Southward of the straits of le Mair, nor one sea-bird, except a disconsolate black Albitross, who accompanied us for several days, hovering about us as if he had lost himself, till Hatley, observing, in one of his melancholy fits, that this bird was always hovering near us, imagin’d from his colour, that it might be some evil omen… after some fruitless attempts, at length, shot the Albitross, not doubting (perhaps) that we should have a fair wind after it.’ These words were reborn as:

‘God save thee, ancient Mariner! From the fiends, that plague thee thus!- Why lookst thou so?’ – ‘with my cross-bow I shot the ALBATROSS.’

Behind this coming together of ideas another scarcely believable coincidence is hidden. Hatley’s ‘melancholy fits’ had a cause. Some years before he had been sailing on a privateer called the Cinque Ports along the west coast of South America when they put in at the uninhabited offshore island group of Juan Fernández. The ship was in poor condition and the first mate, Alexander Selkirk, remonstrated with his young captain when he gave Selkirk orders to sail before repairs could be completed. Selkirk said the ship was unsafe and he would rather be left there, and he was. He survived four years and four months before being picked up by another privateer, Captain Woodes Rodgers. The Cinque Ports had sunk, but one of the survivors had been captured by the Spanish and worked for years as a slave in a silver mine. That man was Simon Hatley. Selkirk was briefly a celebrity, but he was immortalised under another name by a writer who turned his adventure into a novel. The author was Daniel Defoe; the book was Robinson Crusoe. The otherwise unknown Hatley helped inspire two of the classics of his age.

The narrative of the Rime takes place in the cold south (Antarctica’s discovery was still twenty-one years off) then the tropics, but nowhere is clearly recognisable. Coleridge didn’t want it to be. The ship has no name nor does any character in it. There are no officers, no cargo and no ports. At the time he wrote the Rime the longest sea voyage Coleridge had made was to cross the River Severn near Bristol. The Rime is a spiritual journey; every section except the last ends with a direct or indirect reference to the Cross of the Sacrament. He employed two animal images, the killing of the albatross, for sin, and the blessing of the water snakes, for redemption. He used them to affirm that all life is part of one moral system.

2

William Who?

A Merchant Goes Astray

WILLIAM SMITH (1790–1847?)

The captain of a small English merchantman sails far south of Cape Horn to avoid a storm and finds an unknown island on which a ghost ship has been wrecked, providing him with his coffin.

You’d think discovering one of the seven continents would make you famous, although America preserves the name of the navigator Amerigo Vespucci, who definitely didn’t discover it. Columbus long got the credit for discovering the Americas, despite two objections. Firstly Leif Erikson had already been there in the tenth century, and secondly Columbus spent the rest of his life denying it was a new continent; you can hardly discover what you deny.

The last continent to be discovered was Antarctica. Two hundred years ago – two human lives – no one knew it existed, although in summer it is the size of the USA and Mexico combined, and doubles in size in winter when the surrounding sea freezes. Surely its finder would become a historic figure on a par with Columbus. He didn’t.

Odder still, the ancient Greeks named the continent long before it was discovered. They believed that the world must be in balance, so to counterpoise the vast earth, there must be an anti-earth, or Antichthon, moving unseen round the other side of the sun. As there were large temperate land masses in the north of the earth, there must be similar temperate continents in the south, beyond the broiling tropics. They called it the Unknown Southern Land, translated into Latin as Terra Australis Incognita. The southern land would be different, and must be separated from the world the Greeks knew by a strait of water, for these two worlds could not touch: like matter and anti-matter. Centuries rolled by; Europeans voyaged towards all points of the compass, but no one found a land that matched the ancients’ ideas of a balmy southern continent. Yet belief never wavered; Terra Australis Incognita became a thirst for a southern world which the Americas, for all their riches and romance, did not slake. Every scrap of rock glimpsed through a gale became the tip of a peninsula reaching out from the southern paradise. In 1598 five Dutch ships sailed through the Strait of Magellan and one, under Dirck Gherritz, was first separated from the others by fog, and then driven south in a storm. Accounts said that at 64°S he had seen mountains covered in snow, looking very like Norway, which might have located him at the south end of the South Shetland Islands off the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. Until the nineteenth century he was given credit for sighting Antarctica. But his own writings made no such claim; only when they were translated in 1622 was that passage added.

In 1811, forty years after Captain James Cook concluded there was a frozen southern continent, a consortium of five businessmen was gathering funds to build a 216-ton brig. One of them was a young man called William Smith, born on 11 October 1790 in the coastal village of Seaton Sluice, Northumberland. In the baptismal register his name is sandwiched between those of babies born to pitmen, glass-workers, farmers and sailors. He grew up three miles farther north in the coal port of Blythe, where, judging from the standard of his letters, he received a competent education. Aged twenty-one he was the master and owner of the Three Friends. Williams had also worked in the Greenland whale fishery and was a confident ice-pilot: a specialist job. The brig was finished the next year, and since two of the other principal three shareholders were also called Williams, they imaginatively christened it the Williams. Within three years they were early players in the new trade with South America. Another four years on, she was in Buenos Aires with her twenty-two-man crew preparing to make a voyage which usually took around six weeks, sailing west round Cape Horn to Valparaiso in Chile. Chile was one of the new republics rising from the ruins of the Spanish Empire, declaring independence in 1818. Britain actively assisted the fledgling republics. It wasn’t high-principled support for personal freedom which spurred Britain on; at this time no British woman had the vote, and only those men who owned property. It was eagerness to open up new markets for its trade goods, displacing Spain, its trading and colonial rival. Britain provided vital naval support under the brilliant maverick, Lord Cochrane. The busy man in Valparaiso charged with protecting British interests in Chile during this turmoil was Captain Shirreff of HMS Andromache.

However, Spain’s New World empire had propped up her antique economy and European ambitions for three hundred years; she would not surrender South America without a fight. One of King Ferdinand VII’s responses was to send out more troops from Spain in a squadron of four ships including the powerful seventy-four-gun warship San Telmo under Captain Joaquín Toledo. The squadron encountered terrible storms off Cape Horn and was driven far south of their usual sailing routes. Dismasted and rudderless, the San Telmo was towed until she began to imperil the towing vessel, and she was cut loose on 4 September 1819 at 62°S. The San Telmo’s 644 men, coffined in the helpless hulk, drifted south.

Into the hold of the Williams went the usual miscellany of trade goods, including nine cases of pianos, five cases of hats, and one of eau-de-cologne, tobacco, medicine and cloth. There was also a consignment that typified how British manufacturing created dependent markets round the world. Samples of hand-woven ponchos had been taken back to England and replicated on northern steam looms for a fraction of the cost. Gauchos would now buy their ponchos from Yorkshire. Although it was still the southern summer, Captain William Smith met strong contrary winds south of Cape Horn and decided to head further south and take a calculated risk of encountering ice, whose dangers he was familiar with, rather than be at the mercy of a storm over which he had no control. He was not an explorer, adventurer or a geographer, he was a businessman reducing his risks.

What happened next is poorly documented. There is no surviving original document, just partial copies and contemporary reports referring to papers now lost. On 19 February, he found himself in a south west gale stiffened with sleet and snow. Coming up to daybreak at 06:00, where the charts showed open ocean, he saw land. He recorded in his log, ‘Land or Ice was discovered ahead bearing SE by S distant about two leagues, blowing hard gales with flying showers of snow.’ He logged his position as 62°15´S and 60°01´W. In the afternoon the weather improved: ‘4pm tacked ship, the land or islands bearing SEbE to ESE about 10 miles, the weather fine and pleasant, when discovered to be land a little covered with snow.’ The skies soon told Smith the foul weather was ready to return; at 18:00 with whales and seals all around, he resumed his course to Valparaiso.

Smith anchored beneath the city’s steep hills, only to find the British representative Captain Shirreff was in Santiago, so Smith spoke to the most senior officer, Captain Thomas Searle, of the forty-two-gun warship Hyperion. Searle was so startled at the news he forbade them to go ashore where grog would loosen sailors’ tongues. When Shirreff returned, he quizzed Smith. Had he landed, explored any length of shore? – or at least taken soundings to prove it was real land, and not ice, or one of the many islands seen once at a distance and never again? (A century before, Jonathan Swift had lampooned such fugitive sightings when he invented the flying island of Laputa in Gulliver’s Travels.) Williams had done none of these things. It wasn’t that Shirreff didn’t believe him, but in Chile he had many tasks of clear and pressing importance to British interests. He required solid evidence before pursuing other ends. Smith said he would sail a similar course on the way back, but when he got to the same area on 16 May, the weather was poor; winter had begun. The encircling ice began to rip off the expensive copper plating which protected the vessel against shipworms. He left without re-sighting land.

But Smith knew what he had seen. With his next cargo, in October, he swept south again and at 18:00 on the 15th, he reached the position where he had logged land, and saw it again. This time he was determined to prove his case. He was probably looking at King George Island, and he followed the land eastward and named features. On 17 October, at a place now called Venus Bay on Ridley Island, also known as Ridley’s Island, ‘Finding the weather favourable, we lowered down the boat, and succeeded in landing; found it barren and covered in snow; seals in abundance. The boat having returned, and been secured, we made sail.’ That laconic, business-like record was the last time anyone could record finding a continent. He claimed it for Great Britain, and named it New South Britain. They turned and went 150 miles WSW along the coast of an island chain, and when they finally decided to turn north, still more land was in view. He was later persuaded that since the Scottish Shetland Islands occupied an equivalent latitude in the north, he should re-christen the group the South Shetlands. Smith invested a lot of time in this diversion. This trip took an extra six weeks, so he planned to come back and take seals, to recoup his investment. He also recorded that sperm whales, the most valuable whales of all, were abundant. There were no great words or thoughts on landing, as Antarctica was at last discovered; he had no way of realising the significance. On 18 October he wrote, ‘I thought it prudent, having a merchant’s cargo on board, and perhaps deviating from insurance, to haul off to the westward on my intended voyage.’ He wasn’t going to be an uninsured driver.

Alexander von Humboldt sarcastically observed that there were three phases in the popular attitude to a man who makes a great discovery. Firstly men doubt its existence, next they deny its importance, finally they give the credit to someone else. Smith suffered all these. Some British journalists were not convinced Smith’s reports were genuine. The Edinburgh Magazine mocked: ‘At first we treated it as an Irish or American report, both of which are generally famous for not being true.’ Then, as soon as word of Smith’s discovery spread, American newspapers proclaimed that these islands had already been discovered by US sealers. Baltimore’s Niles Weekly Register for 23 November 1822 read: ‘It is now well-known that some of these hardy people had visited what is regarded by the English as newly discovered land as early as 1800.’ There was no written evidence but that, they said, was not surprising since sealers were secretive about their movements: knowledge was money. In which case why were the beaches still swarming with seals after twenty years’ sealing? Rookeries were wiped out in two seasons. Tellingly, records of sealers in the period 1812–19 show that no vessel came home with catches exceeding expectations from known rookeries, but when the sealers followed Smith to the Peninsula, catches soared, and the Antarctic fur seal was all but exterminated by 1822.

The partially informed sharpened their quills and recycled old lies. The prestigious Edinburgh Philosophical Journal carried a report of Williams’s discovery illustrated with a chart showing a southern continental mass labelled Terra Australis Incognita lying between 54-58°S and 40-53°W. They claimed this was the previously reported land mass which William Smith had merely re-discovered. This despite the fact that Captain Cook had sailed through that area and seen only ocean and ice. The chart was an old fraud, based on a Mercator map of 1569, copied in turn from a small world map of Oronce Finé drawn in 1531. But if there was money to be made, any pretext might do to claim prior discovery. What was really needed was an official voyage to formally take possession and claim it for their sponsor’s country. Britain, handily established in Chile, was first off the mark. One factor which helped Shirreff make a case for diverting effort south was that Britain had no convenient base from which to help exploit the emerging trade markets in South America. The Falklands had been abandoned in 1774 and would not be effectively occupied again until 1833. Their nearest colonies were South Africa and Australia, too remote to help.

Smith’s landing secured Shirreff’s ear. Shirreff was only thirty-four but he had been in the Navy since he was eleven years old. He wanted to help and he could spare some men from the Andromache, but the vessels themselves were committed. The Williams had been chartered to an entrepreneur called John Miers to ship heavy technical equipment from Valparaiso to Concón. But Miers was also a man with strong scientific interests; he would later become a Fellow of both the Linnaean Society and the Royal Society, and bequeath over twenty thousand specimens to the British Museum. He kindly agreed to shelve his plans and let Shirreff charter the Williams to investigate the South Shetlands.

Command of the vessel was given to Captain Edward Bransfield, born in Cork, Ireland in 1785. He had been pressed into service when only eight years old. Now the word was out, it would be a race to go south and take the initiative in exploring the new territories. That summer, fifty British and American vessels followed the Williams’s wake, over the toughest seas in the world, to see what money a man might make there. Shirreff’s orders to Bransfield looked for a longer commitment. They read:

You will ascertain the natural resources for supporting a Colony and Maintaining a population, or if it be already inhabited, will minutely observe the Character, habits, dresses, customs and state of civilisation of the Inhabitants, to whom you will display every friendly disposition.

It seems quaint to imagine native Antarcticans waiting to exchange diplomatic niceties, but at this time William Parry and John Ross were voyaging high above the Arctic Circle and meeting native peoples surviving in far harsher climates than Smith had reported. Might they not meet the southern equivalent? What’s more, The Literary Gazette had reported William Smith as saying of the South Shetlands that ‘firs and pines were observable in many places.’ It continued: ‘The climate of New Shetland would seem to be very temperate, considering its latitude; and should the expedition now sent out bring assurances that the land is capable of supporting population, – an assumption which the presence of trees renders very probable, the place may become a colony of considerable importance.’ The Literary Gazette had exaggerated a line in William’s log of an observation he made in thickening weather as he prepared to leave: ‘could perceive some trees on the land the southward of the cape.’ He was deceived. Antarctica’s largest plant is a few inches high.

Captain Edward Bransfield, with William Smith and forty-three others on board, sailed from Valparaiso in late December and sighted Livingston Island in the South Shetlands on 16 January 1820. They made their way north-east along the northerly coasts of the large islands of the group, then round to the south side of King George Island, where Bransfield landed in what is now King George’s Bay, after George III of England. It is one of the nice perks of being a monarch that you sit snugly on your throne while others suffer the discomforts of finding places to name after you.

These islands are a relatively warm part of Antarctica, their climate softened by the surrounding ocean; during their voyage, the lowest temperature recorded was –1°C. Because of this, and the ease and economy of servicing a base there, it is now the home of many Antarctic stations including those of nations with subterranean profiles in the annals of Polar history, such as Papua New Guinea. However it isn’t hot, and many of the seamen transferred from the Andromache in Valparaiso had settled down to life in a Mediterranean climate and sold off all their warm clothes. They now suffered miserably from exposure.

Although they had taken ninety days’ water, leaking barrels made them anxious to replenish stocks. From 22 to 27 January they anchored off a small island dominated by an extinct volcano and named it after the main inhabitants, Penguin Island, before beating them aside to go ashore. It is a short climb up from the beach, through soft ash and cinders, to the main crater, within which lies a smaller cone. There was still breath to spare for more words of possession and a volley of small arms. From the 170-metre-high summit, there is a breathtaking view across the narrow channel guarded on the far side by Turret Point on King George Island, a cluster of three stacks linked to the land by a wishbone of shingle beaches. They crossed over and soon found a more convenient spring, and encountered elephant seals on the beach. They decided to kill some to make oil. At that time of year elephant seals, which weigh up to four tons, are moulting, which is uncomfortable and puts them in a bad mood. Although they are not agile on land, they are powerful and deceptively flexible. One sailor approached a seal from behind, but was caught flat-footed when it swivelled round and savaged his hand in its immensely strong jaws. The officers contented themselves with safer work: collecting mosses and stones for study.