Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

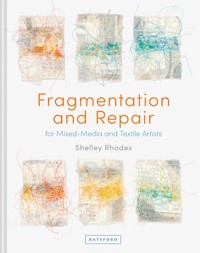

Discover the rich creative possibilities of fragmentation and repair in textile art. Fragmentation and repair are two of the biggest buzzwords in textile and mixed-media art. In this fascinating book, renowned artist Shelley Rhodes explores both concepts, with a wealth of fresh ideas and practical advice. Drawing on her own practice, Shelley explains how she reconstructs and reassembles cloth, paper and other materials to create new pieces, often incorporating found objects and items she has collected over the years to add depth and emotional resonance. From piercing and devoré to patching and darning, techniques include: - Fragmentation of materials, text and image. - Repair using darning and patching along with pins, tape, adhesive and plaster. - The Japanese concepts of wabi-sabi (finding beauty in imperfection) and mottainai (using every last scrap). - Using salvaged and recycled materials, and repurposing household items. - Methods of distressing and manipulating surfaces including weathering, abrasion, burning, piercing, staining and burying. - Collage, working in a series and collecting fragments. Beautifully illustrated with Shelley's own pieces alongside those of other leading artists, this fascinating book is the ideal companion for any textile artist wanting to bring notions of fragility, fragmentation and repair into their own work.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 138

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Fragmentationand Repair

for Mixed-Media and Textile Artists

Shelley Rhodes

Shelley Rhodes, Weekly Stitch Practice. 5 x 12cm (2 x 4¾in) each.

Shelley Rhodes, In Decline (detail).

CONTENTS

Introduction

Historical Fragments

Kantha

Japanese Boro

Discarded and Abandoned

Wabi-sabi

Recycle, Reuse

Salvaged

Altering Surfaces

Manipulation

Weathering

Washing

Soaking

Burying

Abrasion

Staining

Burning and Scorching

Making Holes

Withdrawing Threads

Cutting Holes

Piercing and Punching

Devoré

Burning Holes

Making Changes

Fragmentation

Fragility

Work Large, Then Fragment

Folding

Emotional Fragments

Fragmenting Text

Fragmenting Photographs

Digital Prints

Deconstruction/Reconstruction

Dismantling and Reworking

Reworking Work

Repair

Joining Fragments

Patching and Darning

Stitched Marks

Working in Series

Making a Series

Multiples

Presenting a Series

Collage

Fragments for Collage

Drawing for Collage

Combining Fabric and Paper

Collecting Fragments

Found Fragments

Museum Collections

Displaying Fragments

Containers

Boxes

Presenting Fragments

Mixed Media

Layering

Materials

Using Every Last Scrap

Mottainai

A Daily Practice

Final Thoughts

Contributing Artists

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Index

Shelley Rhodes, Little By Little (detail).

INTRODUCTION

Fragmentation lies at the heart of my work. This book explores how I fragment and deconstruct cloth, paper and objects, before repairing and reassembling to make a new whole. It shows how fragments of found objects can inspire new work, as well as becoming part of the finished piece – perfect if you are a compulsive collector like me. Much of my work involves recycling materials while embracing the concept of wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in imperfection and impermanence. I am drawn to crumbling, stained, weathered surfaces and I show how natural processes can change the appearance and structure of materials, and how these can be replicated in a controlled way.

I refer to historical examples of Japanese boro and kantha, a technique that originated in Bangladesh and West Bengal, showing how tiny fragments of precious cotton were used to patch and repair worn out, distressed fabric to create a new layered, densely stitched cloth. I investigate ideas of repair and reconstruction, not only using stitch but introducing other materials and techniques too. I also demonstrate how previously completed work can be reworked.

I explore the power of multiples and how working in series can enhance the impact of individual pieces. I show how museum displays can be used to inspire content and presentation of work. Finally, I investigate the Japanese concept of mottainai, meaning to use every last scrap, as I demonstrate how tiny fragments can be used in collage and assemblage as well as becoming small works of art in their own right.

Shelley Rhodes, Stitched Grid. 12 x 46cm (4¾ x 18¼in).

Shelley Rhodes, Coral Semblance. 15 x 10cm (6 x 4in) each.

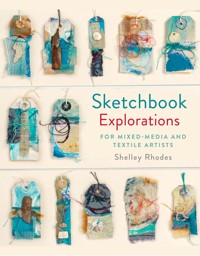

I share techniques of fragmentation and repair that I and other artists use in textile and mixed-media work. As always, I keep a record of my ideas, the progress made and notes regarding technique in workbooks, notebooks, sketchbooks or journals, and encourage you to do the same. (For further ideas about working in this way, refer to my first book, Sketchbook Explorations.) I have included examples of techniques that I use, with some suggestions that I hope you will try.

HISTORICAL FRAGMENTS

For centuries, piecing, patching and repairing cloth were a necessity for many different cultures. Ancient fragments of cloth up to 12,000 years old have been discovered in countries such as Egypt, China and Peru. In Europe, layers of quilted fabric, thought to have been used as part of a soldier’s armour for warmth and protection, have been found dating back to the early Middle Ages. One of the earliest surviving complete patchworks is a coverlet dating from 1718.

Quilting

Quilting is a method of stitching layers of material together – usually two layers of fabric with padding or wadding in between. Quilts can be created using whole pieces of cloth but in this book my focus is on quilts that use piecing and patching for the top layer. Many pieced quilts are joined in regular, geometric patterns, or from patchwork blocks made using a paper template and stitched together in a grid format. However, pieced quilts can be bold and free-form, like the quilts of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. My work tends to be influenced by less formal methods of patching and piecing cloth, such as Japanese boro (see here).

Not all patchwork is quilted. Jogakbo is a style of Korean patchwork traditionally used to make wrapping cloths (known as bojagi). Geometric-shaped scraps are sewn together in an irregular, improvised way, using a special seaming technique to create a flat seam, which gives the cloth the appearance of a stained-glass window.

Patched and stitched cloth details.

Traditional kantha, made in East Bengal, c. 1885. Embroiderers’ Guild Collection.

KANTHA

The word ‘kantha’ is derived from Sanskrit, denoting a rag or patched garment. They are double-sided embroideries created from worn-out saris and dhotis, made in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent. It is unclear when the making of kantha first began: the earliest mention in literature dates from 500 years ago, but the oldest surviving examples originate from the early nineteenth century. Recycling, repurposing and the stitching of layers of cloth together lie at the heart of traditional kantha making. Traditionally, white saris with coloured borders were worn, and when these became old and threadbare, the long pieces of fine cotton cloth were folded into three or four layers and held together with running stitch.

Some traditional kanthas are richly embroidered with scenes and domestic objects from everyday life. Others depict whimsical figures and quirky animals and birds, or have more abstract geometric shapes, or floral and leaf motifs. These motifs are ‘drawn’ with running stitch, using a thread that contrasts in colour, and then filled in with decorative patterns. In old kanthas, the coloured threads were sometimes withdrawn from the border patterns woven on the edges of the saris. Other stitches besides running stitch were also used for the filling stitches, such as back stitch and stem stitch; the placement and density of the stitches affects the texture of the cloth, causing a rippling on the surface. Traditionally, kanthas were made by women and used for household items such as bed quilts and for swaddling babies, as the cloth was usually soft, warm and comforting.

Today, recycling and repurposing continues, using coloured and printed saris in which fragments are pieced and patched together in layers. Multiple rows of running stitch unify and hold the layers in place. There are many stitch co-operatives run on a commercial basis, some creating exciting contemporary twists on traditional techniques, and although the pieces they make are not traditional kanthas, they are still referred to as kantha.

Contemporary cloths using kantha techniques (details).

Shelley Rhodes, Not Quite Kantha. Kantha techniques combined with collage, plaster and clay slip. 27 x 31cm (10¾ x 12¼in).

Dorothy Tucker, Plates and Leaves. 33 x 109cm (13 x 43in).

Dorothy Tucker’s stitched work draws on traditional ways of making kantha. Plates and Leaves is made from a fine cotton sari, folded into four layers. The length of the piece and the inclusion of the woven borders reference the sari from which it was made. She explains:

‘A vertical grey line, just visible under the top layer, makes use of a stripe woven into the sari end. Stripes like these, which often feature on old traditional kantha, inspired me to insert strips of coloured cotton underneath the top layer and also to add patches of colour on top. Once the fabrics have been positioned, the layers are secured with lines of even running stitch. Domestic objects are often depicted on traditional kantha, which led me to use plates and leaves on this piece. All the motifs are outlined, then coloured and filled in with stitched patterns. Finally, all the remaining spaces are quilted.’

Not quite kantha

I often think of my work in terms of being ‘not quite kantha’, as I take the essence of kantha making but work in an inventive, experimental way in order to make contemporary pieces. All samples seen here are made from at least three layers, held together using simple repetitive stitch, and examples 2–5 introduce a variety of non-traditional materials. Working small allows extensive experimentation and exploration before taking any ideas forward into larger pieces of work (see work on here).

Example 1 A traditional approach using lightweight layers of fine fabric joined with rows of running stitch.

Example 2 Combining soft, lightweight fabric with other materials, including wool blanket, felt, paper and plastic.

Example 3 Creating ‘alternative stitches’ by using fine wire, staples, twine, raffia or pins. Stitches do not have to run in straight lines. Layers are held together with knots, tied threads, couching or other decorative stitches.

Example 4 Trapping fragments within the layers using natural or man-made objects, such as pressed leaves and flowers, tiny twigs, pebbles, sea glass, shells, rusty objects or plastic fragments. Flat objects work best; once stitched, metal items can be wetted and left to rust and stain the cloth.

Example 5 Coating the stitched fabric with media such as paint, plaster, gesso, clay slip and wax. Samples can be cracked, scratched and coloured, then restitched.

Shelley Rhodes, In the Canyon (detail), with layered cloth with running stitch inspired by kantha.

JAPANESE BORO

The term boro is derived from a Japanese word that translates as ‘tattered, worn out, torn and crumbling’ and describes heavily patched and repaired clothing and bedding made through necessity in the far north of Japan.

Boro garments were work clothes made and worn by families of poor fishermen and peasant farmers in the late nineteenth century in an area called Aomori, where winters are extremely harsh. Essentially made from rags, repaired and patched with many layers stitched together, these utilitarian garments were also altered and reassembled into bed covers, with one item utilized to repair another. Fabric scraps were used to patch holes and thin areas, which was repeated again and again, increasing the layers and adding greater strength to the material.

Japanese boro yogi sleeping garment, shaped like a giant kimono, late 1800s to early 1900s.

Japanese boro patchwork futon cover with sashiko stitching, late 1800s to early 1900s.

In the north of Japan, clothing was usually made from hemp, which is rough and scratchy and cold in winter, so layers were stitched together and sometimes padded with hemp fuzz to add insulation, like a form of wadding. Further south, towards what is now Tokyo and Kyoto, farmers wore cotton, but the Aomori region was too cold to grow cotton, and only a small quantity of this material found its way north, usually via seafaring traders, until the railway line was opened at the end of the nineteenth century. As a result, cotton fabric was rare and expensive, so the tiniest snippets were saved as they were very precious and valuable. Cloth was handed down from one generation to the next, and young girls would have tiny scraps of cloth as a dowry to take with them when they married.

Japanese boro repairs (details).

Until relatively recently, boro was regarded as a sign of poverty and therefore seen as shameful. It was not until the mid-twentieth century that these garments, futon covers and patched cloths were collected and preserved, largely through the efforts of Chuzaburo Tanaka, who recognized their importance as items of historical and cultural significance. He brought boro textiles to the world’s attention by setting up and displaying his collection in the Amuse Museum in Tokyo (now sadly closed); I was allowed to handle items in the collection when I visited the museum and some of the garments are extremely heavy due to many layers being stitched together.

Cotton sakabukuro sake bags

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Japanese sake brewers used cloth bags, known as sakabukuro, to filter sediment from unrefined sake; the bags were filled then hung, allowing refined sake to drip out into collection vats. Every summer, fermented persimmon juice was applied to the bags to strengthen them and infuse them with antibacterial properties. They became stained and variegated until they almost resembled brown leather. If the bags became damaged, they were carefully patched and hand stitched using thick cotton threads to extend their life. These essential repairs are a wonderful example of wabi-sabi (see Discarded and Abandoned, here).

Japanese sakabukuro (cotton sake bag), early to mid-1900s.

These traditional practices have influenced my own work as I employ methods of repairing, piecing, patching and staining. I always keep the smallest leftover scraps and have bags of tiny fragments saved to reuse. Working this way allows flexibility, as sections can be cut, moved and restitched. If I am unhappy with an area, I can simply cut and reassemble, or cover it with a patch of fabric. Small sections can be worked before joining to become a larger piece, making work portable and always close to hand when I have time free, however short.

Shelley Rhodes, Kantha Fragments (details).

Shelley Rhodes, Marked (detail). Hanging with patches and repairs. 210 x 78cm (82¾ x 30¾in).

DISCARDED AND ABANDONED

I am drawn to things that have been discarded, lost, left behind or abandoned. This could be on the coast, in the countryside or in an urban setting. I look closely, constantly observing, recording and collecting, as I seek out broken, mundane, neglected and overlooked things.

WABI-SABI

Finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence is the aesthetic behind the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi. It is about encompassing natural decay and ageing, and appreciating something that is weathered and showing signs of patina, rather than an item that is shiny and new. It could be something that is fragmented or uneven; it may be a piece that has been repaired, but showing and rejoicing in the repair, rather than trying to hide or disguise it. It is about noticing and reacting to small details rather than grand gestures. It is also about being less materialistic, reusing the things we already have by mending, recycling and reinventing. It is transient and ever-changing, sometimes unfinished and incomplete, but often quiet, minimal, calm and uncluttered.

Many of these ideas have an influence on my work. Most of the fabric I use is repurposed and recycled, such as bed linen, tablecloths, handkerchiefs, curtains and garments. I like the soft, worn quality of well-used fabric, which may include small holes, marks and stains. Colours are usually slightly faded and gentler than they would once have been. Sometimes, I unpick the seams to reveal how the fabric would have looked before repeated washing, handling and general wear and tear. This recycling also has a positive impact on the environment.

I photograph examples of wabi-sabi to use as inspiration for drawing and mark-making, or for extracting a colour palette. I am drawn to crumbling, derelict buildings, to cracked plaster and peeling paint that reveals layers of colours beneath the surface; to painted metal that has been weathered and distressed over time, perhaps affected by salty seawater. Looking closely reveals amazing colours and beautiful marks that are often perfect in their imperfection.

‘Being creative is seeing the same thing as everybody else but thinking of something different.’

Albert Einstein

Wabi-sabi photographs.

Shelley Rhodes, Backstreets Series. Mixed media on MDF. 33 x 15cm (13 x 6in).

Backstreets is a series of mixed-media work exploring surface texture, inspired by the crumbling buildings I photographed while visiting Cuba. Cloth was fragmented, manipulated and stitched, then coated with layers of paint, plaster and clay slip, partially embedding the stitches (see Mixed Media, here). Fragments were joined and further stitched marks made before they were collaged onto boards. Colour was applied with layers of ink, pigment, oil and wax, before scratching, nailing and wrapping.

Corrugated iron photographs.

Shelley Rhodes, Corrugated Series II. Mixed media incorporating found metal. 40 x 29cm (15¾ x 11½in).