13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

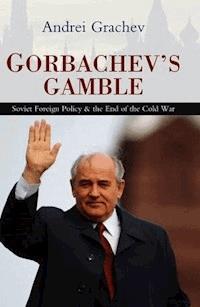

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Gorbachev’s Gamble offers a new and more convincing answer to this question by providing the missing link between the internal and external aspects of Gorbachev’s perestroika. Andrei Grachev shows that the radical transformation of Soviet foreign policy during the Gorbachev years was an integral part of an ambitious project of internal democratic reform and of the historic opening of Soviet society to the outside world.

Grachev explains the motives and the intentions of the initiators of this project and describes their hopes and their illusions. He recounts the story of the internal debates and struggles in the Kremlin and behind-the-scene decisions that led to the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the break-up of the Warsaw Pact and eventually the demise of the Soviet Union itself.

The book is based on exclusive interviews with the leaders of the Soviet Union including Gorbachev, personal notes and diaries of their assistants and advisers and transcripts of the discussions inside the Politburo and Secretariat of the Central Committee. Together they constitute a multi-voice political confession of a whole generation of decision-makers of the Soviet Union that enables us better to understand the origin and the breathtaking trajectory of the events that led to the end of the Cold War and the unprecedented transformation of world politics in the closing decades of the 20th century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 515

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

GORBACHEV’S GAMBLE

To Alena, and to my grandson Maxim, with the hope that one day he will read this book and will be struck by the contrast between the world in which he will be living and the absurdity and fears of the one that had been inherited by his grandparents.

GORBACHEV’S GAMBLE

Soviet Foreign Policy and the End of the Cold War

Andrei Grachev

polity

Copyright © Andrei Grachev 2008

The right of Andrei Grachev 2008 to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2008 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5532-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 11 on 13pt Palatino

by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk

CONTENTS

The Gorbachev Years: A Chronology

Preface and Acknowledgements

Introduction

1

Preparing the Change

Dual-Track Diplomacy

The Military-Diplomatic Complex

‘Moles’ in the Corridors of Power

Cracks in the Monolith

2

Ambitions and Illusions of the ‘New Political Thinking’

Training for Leadership

First Exercises in Foreign Policy

Building the New Team

Summits in Paris and Geneva

A ‘Tail’ of Soviet Diplomacy?

‘New Thinking’ or Ideology Revisited?

From Philosophy to Politics

Reykjavik – ‘the Failed Summit’?

‘New Political Thinking’: Rules and Tools

3

Breaking the Ice

Untying the Reykjavik ‘Package’

Withdrawing from Afghanistan and Retiring from the ‘Third World’

‘Abandoning’ Eastern Europe

Destroying the Berlin Wall

4

Up to the Peak and Down the Slope

Gorbachev’s ‘Anti-Fulton’ Speech at the UN

1989 – the Year of ‘the Great Turn’

Malta – a Belated Triumph

On the Other Bank of the Rubicon

The War in the Gulf and Shevardnadze’s Resignation

The G7 in London: The Summit of a Last (Lost) Chance

5

The Winds of Change

Notes

Bibliography

Index

THE GORBACHEV YEARS: A CHRONOLOGY

1982

•

November. Brezhnev dies, replaced by Andropov as Soviet leader

1983

•

March. Reagan denounces the USSR as ‘the evil empire’; announces the Strategic Defense Intitative

•

August. KAL flight 007 shot down over the Sea of Okhotsk

•

November. NATO ‘Able Archer’ ‘nuclear scare’ (nuclear war gaming) exercise

1984

•

February. Andropov dies, replaced by Chernenko

•

December. Gorbachev goes to the UK at the head of a Soviet Parliamentarian delegation. First meeting with Margaret Thatcher

1985

•

March. Chernenko dies. Gorbachev is elected Party’s General Secretary

•

October. Gorbachev’s official visit to France at the invitation of François Mitterrand

•

November. US–Soviet summit meeting in Geneva. First meeting of Gorbachev with Reagan

1986

•

January. Soviet government’s Declaration proposing to rid the world of nuclear weapons by the year 2000

•

February–March. 27th Congress of Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Announcement of reforms in internal life and radical changes in Soviet foreign policy

•

April. Explosion of nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl power plant

•

October. Gorbachev–Reagan meeting in Reykjavik

•

December. Andrei Sakharov returns to Moscow from his forced exile in Gorky.

1987

•

May. West German amateur pilot Mathias Rust lands on Red Square near the Kremlin. Gorbachev fires the Minister of Defence Marshal Sokolov and top commanders of the Soviet air-defence

•

December. Gorbachev’s official visit to the USA. Signing of the INF Treaty in Washington

1988

•

April. Signing of Geneva Agreements on Afghanistan

•

June–July. 19th Party Conference in Moscow. Gorbachev proposes major reform of state institutions, including competitive elections for a new legislature

•

September. Andrei Gromyko ‘resigns’ from the post of Chairman of Praesidium of Supreme Soviet, replaced by Gorbachev

•

7 December. Gorbachev addresses the UN General Assembly with a speech in which he announces the deideologization of Soviet foreign policy, proposes the renunciation of the use of force in international relations and confirms respect for the right of each people to freely chose their political system

1989

•

February. The Soviet government announces the completion of the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan

•

May. Bush in his first presidential speech on the Soviet Union pledges to move ‘beyond containment’

•

Gorbachev’s visit to the People’s Republic of China – first Sino-Soviet summit in 30 years

•

June. Election in Poland becomes a political triumph for Solidarity

•

August–September. Massive exodus of East Germans after the opening of the Hungarian border

•

October. Gorbachev comes to the GDR for the celebration of its 40th anniversary

•

9 November. The Berlin Wall comes down

•

December. Gorbachev meets Bush at the ‘seasick’ summit in Malta

•

Václav Havel is elected the new President of Czechoslovakia

•

Nicolae Ceaus¸escu and his wife are executed by a firing squad after a hasty trial

1990

•

February. American, Soviet, British and French foreign ministers during a meeting in Ottawa agree on a ‘2 + 4’ formula of negotiations to solve the problem of German reunification

•

March. In elections East German voters back the pro-unification party allied with Helmut Kohl

•

May–June. Bush–Gorbachev summit in Washington and at Camp David

•

July. Kohl comes to Moscow and is invited by Gorbachev to his native region in the North Caucasus, where the two leaders finalize the agreement on the reunification of Germany and the future Germany’s affiliation to NATO.

•

August. Iraqi troops invade Kuwait. Baker and Shevardnadze issue a joint condemnation of the invasion

•

September. Bush–Gorbachev meeting in Helsinki to discuss the Persian Gulf

•

October. East and West Germany unite

•

Gorbachev is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

•

November. Paris Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe adopts the Charter of a New Europe. NATO and Warsaw Pact leaders sign a Treaty on Conventional Forces in Europe

•

The UN Security Council passes Resolution 678 authorizing the use of force to impose on Saddam Hussein the implementation of the UN resolutions on the evacuation of Kuwait

•

December. Shevardnadze resigns as Foreign Minister

1991

•

January. In Vilnius Soviet troops storm the local TV station, killing 14 Lithuanians

•

Bessmertnykh appointed Foreign Minister

•

The Persian Gulf War begins with an air strike on Baghdad

•

February. The leaders of the Warsaw Pact announce their decision to dissolve the military structure of the alliance on 1 April. (The Political Consultative Council is dissolved on 1 July.)

•

March. Soviet citizens (in nine republics) vote massively in a referendum in favour of retaining a federal Union

•

June. Yeltsin elected President of the Russian Republic

•

July. G7 leaders invite President Gorbachev to their summit in London

•

July–August. During a US–Soviet summit in Moscow, Gorbachev and Bush sign the START I Treaty.

•

18–21 August. Attempted coup against Gorbachev by hard-liners

•

Upon his return to Moscow from Crimea, where he was sequestrated by the putschists for three days, Gorbachev resigns from his post of the General Secretary of the Communist Party. The activity of the CPSU is suspended at the instigation of Yeltsin

•

October. Gorbachev and Bush meet in Madrid on the occasion of the Conference on the Middle East

•

November. Gorbachev reappoints Shevardnadze to the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs

•

8 December. The leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus meeting in a forest near Minsk declare the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

•

25 December. Gorbachev resigns from the post of the President of the USSR. The Soviet Union ceases to exist

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe this book to a combination of various, occasionally accidental circumstances as well as the important contribution and assistance of certain specific persons and institutions. It was certainly chance – indeed, the chance of a lifetime – that gave me the privilege of assisting and participating, to the degree of my capabilities, in an exceptional political adventure: Soviet perestroika. Initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev and a group of his followers, it radically transformed the former Soviet Union and played a crucial role in the course of world history at the end of the twentieth century.

As a member of the circle of Gorbachev’s advisers, I could closely observe the unfolding scenario of an exciting, unpredictable drama, the political ‘revolution from above’ that had as its goal the return of an immense country to the course of its natural history, reconciling it with the rest of the world. Conscious that I was witnessing History in the making, I started to take notes during my conversations with Mikhail Gorbachev and at numerous sessions and meetings with his closest colleagues, aides and political allies (some of whom later became his most severe critics or even political adversaries).

These notes and observations served me well during the preparation of my several previous books, where I tried to explore the origins and internal roots of perestroika, a phenomenon which otherwise may have seemed to arrive as a sudden thunderbolt within an apparently all-powerful, one-dimensional totalitarian universe. This book, a continuation of these reflections, has been written with the intention of establishing the link between the attempt to democratize the pol itical system and the transformation of foreign policy, a transformation that resulted in the end of the Cold War.

If my first stimulus for writing this book was to record and try to explain a turning point of modern politics, to examine a historic episode that had a profound effect on the world political scene, there was another motive as well. In my view, despite the enormous literature over what is now almost two decades since the end of the Cold War, despite the various explanations and versions of events found in numerous analytical publications, research studies and memoirs (of the principal as well as secondary actors), the origins of this unprecedented historic upheaval are still inadequately explored or understood.

Given a political shock of such dimension, it is not surprising that there have been various, sometimes conflicting interpretations of the end of the Cold War. Yet the particular feature of the events that shook the world in the late 1980s and early 1990s is their contemporary relevance, their continuing effect on the current international situation and even on today’s politics. For this reason it is important to have a better understanding of what really happened during those years and why. In the relations of the Soviet Union with its Western partners, what were the motivations and the intentions of the new Soviet leadership after the election of Gorbachev? How was the delicate process of relinquishing the era of confrontation actually handled? Answers to these questions could be of interest not only for historians but also for the decision-makers of today and perhaps of tomorrow as well.

Thus, my intention has been to try to complete the existing picture with the provision of missing details, new information and additional touches that I hope will help to increase our understanding of the meaning of these complex events and draw useful lessons from this unique episode of recent history. Yet it would not have taken the form of a book if I had not been encouraged by others to undertake necessary additional research and to proceed with the realization of this project.

I wish first of all to thank Alex Pravda, the former Director of the Russian and Eurasian Studies Centre at St Antony’s College, Oxford, who participated in the original formulation of the concept and joined me in the process of interviewing and recording for posterity the testimony of numerous Soviet decision-makers who were personally involved in the implementation of the policies of those years.

I am profoundly grateful to the many outstanding figures of perestroika, starting with President Gorbachev and his principal colleagues, advisers and aides, but also the many diplomatic, military and academic experts and analysts who agreed to answer our questions and to provide us with precious and exclusive insider information about the functioning and mechanisms of Soviet foreign policy.

I would like also to thank their foreign colleagues, who agreed to share their own recollections with us, in this way allowing us to compare and contrast Western and Soviet versions of what happened behind the scenes. Among them I want to mention particularly the contributions of Presidents Jaruzelski and Iliescu from Poland and Romania, the former Hungarian Prime Minister, Gyula Horn, the former French Foreign Ministers, Roland Dumas and Hubert Vedrine, the foreign policy adviser to Chancellor Kohl, Horst Teltschik, and also the US and UK Ambassadors to Moscow, Jack Matlock and Rodric Braithwaite.

At the time of the final revision and editing of this book I received most valuable expert advice from two anonymous readers who were invited to comment on the manuscript by my publisher, and I want to sincerely thank both of them for the encouragement they have given.

I am enormously indebted to Ellen Dahrendorf for the inestimable contribution she has made to give to my writing a more readable form and also for her enthusiastic support which inspired me to go ahead with the research and book project.

The academic assistance and hospitality offered to me by St Antony’s College, Oxford, which generously accepted me as a senior fellow during the period of my research, was exceptional and extremely helpful.

In conclusion I would like to express my warmest thanks for the support offered to this research by the Leverhulme Trust, without which this book would probably never have appeared.

INTRODUCTION

Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed.

Constitution of UNESCO

The radical shift of Soviet foreign policy and the subsequent chain of events that eventually led to what later came to be called ‘the end of the Cold War’ are justly associated with the name of Mikhail Gorbachev. No one – whether his former political partners in the West or his opponents or most severe critics in his own country – contests the significance of the change he managed to bring about in the world political arena. Most observers seem ready to recognize the value of his strategic vision as well as the tactical skill that allowed him to extirpate ideological antagonism from East–West relations, putting an end to military confrontation and eliminating, it is hoped forever, the danger of a third world war.

There is, however, disagreement about certain aspects of the events in question which continue to provoke debate within Russia and abroad, largely concerned with a limited set of questions, namely: was Gorbachev free to chose other variants for his foreign policy? Could he not have obtained a better ‘price’ from the West in return for introducing such an unprecedented transformation of the foreign policy of the second world superpower? Could the ‘reward’ eventually offered to Gorbachev by the West in the form of more vigorous political support and, in particular, economic assistance have helped him to secure his internal power position which would have enabled him to take his reform project further? Finally, and perhaps the most crucial question: what were the basic internal and external factors that pushed the Soviet leadership and Gorbachev personally to engage in such a breathtaking, politically risky adventure – the promotion of a qualitatively new foreign policy that with great solemnity was designated as the ‘new political thinking’?

Gorbachev’s practical activity in the field of foreign policy produced controversial results. It brought about the end of the Cold War as well as unprecedented change on the international scene, contributing to the advance of democratic forces, the liberation of oppressed nations and an acceleration of the natural course of world history. At the same time, the implosion of a country that had constituted one of the props of the postwar international order contributed to the rise of political instability and a return of old tensions with a proliferation of breeding grounds for new conflicts.

Gorbachev’s own statements on the subject do not always provide absolute answers, including comments made several years after these historic events unfolded. The same can be said of the numerous memoirs by other key political players of the period that have been published in the course of the last fifteen years. Naturally each contribution adds its own particular angle to the recapitulation of the course of events, sometimes confirming but quite often contradicting the versions provided by other decision-makers. Taken together these accounts represent a gold-mine of information about these exciting years of historic change. Yet they do not provide an answer to the main question: ‘Why did it happen?’ To this day, therefore, the sudden ending of the Cold War, surely the dominant feature of the second half of the twentieth century, continues to be one of the most unexpected and perplexing phenomena of our time.

Most Western scholars, with hindsight, have sought to ration alize tumultuous developments that quite often were spontaneous in character; their books tend to present the Soviet leadership’s policies of these years against a monochrome, rather flat background, rarely referring to the difficult com promises that had to be reached on each occasion behind the scenes.1 What also appears to be a common feature of various analyses is a tendency to ignore the fact that the frequent zigzags of Soviet foreign policy during the Gorbachev years represented, above all, one of the most important components of the tremendous political struggle that accompanied the realization of his global project of internal reform.2

Several years after his resignation, in an interview with the author, Gorbachev confirmed that from the very beginning he regarded the radical improvement of relations between the Soviet Union and the West as a basic precondition for the success of perestroika, ‘since without putting an end to the fatal spiral of the arms race we could have drawn the whole world into an abyss and would have had to abandon all our plans for internal reform’.3 This statement by Gorbachev was corroborated by his closest political ally and the chief ideologist of perestroika, Aleksandr Yakovlev. For Yakovlev also, the introduction of radical change in the Soviet Union’s relations with the West and establishment of cooperative relations between the USSR and the outside world represented an integral part of a much broader project: the democratic transformation of the Soviet political system.4

This explanation certainly differs from interpretations of the reasons for the new Soviet foreign policy given by most Western political leaders and analysts, more or less summarized in the formula of Michael R. Beschloss and Strobe Talbott in their book At the Highest Levels. They argue that ‘the improvements in the Kremlin’s behavior were a direct result of forty years of consistent pressure from the West and particularly, for the previous eight years, from the Reagan administration’.5 A more laconic expression of the same view appears in James Baker’s memoirs: ‘Containment had worked,’ announced the US State Secretary, speaking at Princeton on 12 December 1991 in the presence of George Kennan, the author of the ‘long telegram’ sent from Moscow in 1946 in the first months of the Cold War, where the formula appeared for the first time.6

This amounts to a rather simplistic reading of an extremely complicated and controversial historical episode. Explanation of the unexpected ending of decades of ideological and military confrontation between East and West is reduced to one dimension – the determination of Western hard-liners. Having rejected the pacification course advocated by naïve promoters of détente as well as the hopes of ‘realists’ to reeducate communist leaders according to the standards of Western civilization, they chose to wear out the Soviet totalitarian system by imposing on it the unbearable arms race and in this way compel it to capitulation.7

There is an alternative Western interpretation according to which the triumph of the West was not in fact achieved by frontal pressure on the USSR, which only served to encourage the totalitarian regime to maintain the atmosphere of a besieged fortress inside the country as well as throughout the zone of Soviet influence; rather it was the peaceful ‘managed cohabitation’ which in its different forms – from Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik to the provisions of the Helsinki Final Act – managed to stage a trap for the Soviet leaders, obliging them to compete with the West not just in the field of weapons production, where their system proved to be quite efficient, but also in a totally different area. The Soviet Union proved unable to compete when it came to assuring individual freedom and civil rights, or, above all, the creation of decent conditions for everyday life. It was largely this policy that eventually led to the internal decomposition of the Soviet monolith, giving birth to the viruses of pro-Western reformist currents. The shell was bound to crack.

Even a combination of these apparently divergent explanations presents just a part of the picture. It should not be forgotten that the Soviet leaders were just as enthusiastic as their Western adversaries in their efforts to speed up the arms race while hoping to make use of the fruits of political détente. However, the main point is this: those who award the prize for bringing about the downfall of the communist project in the USSR exclusively to Western actors tend to present the Soviet colossus merely as an object to be manipulated by alternative versions of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ Western (primarily American) power. The most crucial factor is ignored if there is no proper analysis of the dynamics of the evolution and internal trans formation of Soviet society, a transformation that has followed a logic of its own, quite apart from externally imposed influence and pressure.

It is understandable that Gorbachev and members of his ‘team’ (Aleksandr Yakovlev, Eduard Shevardnadze, Anatoli Chernyaev, Vadim Medvedev . . .) have challenged the thesis that the West can claim sole credit for an unconditional victory in the Cold War, in view of their personal involvement in the decision-making processes during the years of perestroika. Given the fall of the Berlin Wall, the unification of Germany and the withdrawal from Afghanistan as well as the unprecedented achievements in the field of disarmament, they have convincing arguments to plead their case.8 However there are other quite different Soviet voices – some who from the outset were sceptical of Gorbachev’s project and strategy, others who only later became critics or political adversaries (Yegor Ligachev, Vladimir Kryuchkov, Georgi Kornienko, Anatoli Dobrynin, Valentin Falin . . .), whose testimony confirms, as the reader will see, the endogenous roots of the process that led to a qualitative change in Soviet foreign policy when a new national leader appeared on the scene.9

Nor can we ignore the opinions of Russian politicians, experts and commentators, increasingly audible in Putin’s Russia, who, speaking with hindsight and for evident internal political reasons, prefer to present the end of the Cold War as the result of the naïve or, even worse, the consciously ‘cap itulationist’ policy of Gorbachev and his supporters, who ‘betrayed’ their country’s national interests by surrendering to the perennial Western enemy. Paradoxically, their interpretation of the end of the Cold War as a historic defeat for the Soviet Union or Putin’s description of the disintegration of the country as ‘the biggest geo-strategic catastrophe of the last century’ coincides with the most arrogant Western position that proclaims the absolute triumph of the West over its Soviet strategic rival. Such a view leaves no room for doubt: what happened to the Soviet Union and to the communist regime in general was the result of ‘high treason’ by the initiators of perestroika.

In defence of their political and foreign policy choices, Gorbachev, Shevardnadze, Yakovlev and their other allies argue that what once had been an ‘arms wrestling’ contest between the two superpowers had escalated into a quest for strategic domination via a monstrous arms race that had become a major threat for the whole of humankind. This is why all responsible politicians had to regard the ending of the Cold War as their first priority. It is this assumption that led to the conception of the ‘new political thinking’, soon to be followed by unprecedented practical initiatives by the Soviet leadership under Gorbachev. The extraordinary political moves, the proposals for unexpected compromise, the unilateral gestures and concessions all would have been inconceivable in the framework of the traditional logic of superpower confrontation.

Acting in accordance with the principles and spirit of the new political philosophy, but also, as stated on a number of occasions by Gorbachev, merely following the criteria of the common sense and universal norms of human morality, the authors of the new Soviet foreign policy would not admit that they acted under constraint or were borrowing Western values. The theorists and practitioners of the ‘new thinking’ considered it to be a home-grown product, conditioned mostly by internal problems, and if they referred to Western sources of influence and inspiration, they would mention first of all the ideas to be found in the Russell–Einstein Manifesto, the reports of the Palme Commission or the Club of Rome or other similar appeals calling for an end to the absurd logic of nuclear confrontation and demanding that the attention of world politics be turned to the global problems and challenges facing the human species. For example, such terms and notions in the vocabulary of the ‘new thinking’ as ‘reasonable security’ and ‘non-offensive defence’ were promoted mainly by the Western peace movements and peace research networks in the USA and Western Europe (for example, the Pugwash group or Physicians for Nuclear Disarmament) and not taken from the West’s strategic doctrines.

Moreover, if they admit that there was indeed effective pressure coming from the West which had an influence on the subsequent development of Soviet policy, it was not a question of the military threat or the politics of ‘containment’ but rather the example of successful economic development along with the attractiveness of ideas of political freedom which were, in fact, becoming important factors in the internal evolution of Soviet society.

Paradoxically enough, at least during the first years of perestroika, the new Soviet leaders failed to see the danger of possible economic ruin if the Soviet Union were to follow the United States in a new round of the arms race. Leaders of perestroika, particularly at its initial stage, were barely conscious of the scale of disaster unfolding within the national economy and had only a rather vague idea about its capacity to survive if there were to be an abolition of centralized planning and an end to the administrative command system. One explanation for this, as Gorbachev admitted later, was the fact that even the members of the new Politburo, himself included, had yet to discover the monstrous size of the Soviet military-industrial complex.

Already at the time when I became a member of the Secretariat and later of the Politburo of the Central Committee I was conscious of the fact that neither I nor other members of the Soviet political leadership were getting full information about the real figures for our defence spending. Even at the next stage in my capacity as General Secretary and de facto head of the Soviet state, I had enormous difficulty squeezing out of our military lobby genuine information about the amount of money being poured into this bottomless barrel. First of all, this was because the people in charge had got accustomed to not having to report to anybody about how the money was being used and they certainly did not want to sacrifice their privileged status. Secondly, quite often they themselves did not possess total information.10

* * *

Analysing the motives and expectations of the initiators of the ‘new thinking’ and then comparing them to its balance sheet, one is tempted to conclude that the whole construction rested on a rather shaky foundation. The pioneer reformers of the totalitarian system expected a smooth evolution from rigid Soviet communism to some vague political model combining the social paternalism of the centralized state with a modern social democratic version of capitalism; obviously they were unable to envision all the consequences for the functioning of the highly centralized economy when they attempted simul taneously to impose profound political reform along with the introduction of the logic of the market. Still less could they have foreseen the implosion of the multinational state accompanied by the free-fall of the USSR’s international authority and, with that, the credibility of its foreign policy.

In addition to the above, the Soviet missionaries of ‘new thinking’ also idealistically (some would say, naïvely) believed that once they had proclaimed themselves to be new partners of the West in the quest for peace and stability, their former adversaries would eagerly accept Soviet pledges at face value and would adapt their own policies in a practical way. They hoped that once relieved from the fear of the Soviet threat, the West not only would resist the temptation to profit strategically from the transition crisis of post-communist society, it also would meet them halfway in a common effort to remodel international relations along the lines of their messianic project. However, the fact that the results of their actions proved to be quite different from their initial aspirations does not mean that such an outcome was inevitable.

In order to provide a more stereoscopic image of this unprecedented political adventure, it seemed useful to collect and compare the testimony of a large number of varied political players and top functionaries of the former Soviet Union, the men who were involved in the elaboration and application of major foreign policy decisions. They have often been asked to comment on the same events. The people who were interviewed come from various levels of the Soviet power hierarchy and represent the most important political and state institutions and think-tanks of the Soviet epoch: the Party apparatus, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Defence, the KGB, academics and military industry specialists. Each one of them played an appreciable role on the level of decision-making at different stages, offering expertise or counselling the political leaders. Together with the personal testimony of Mikhail Gorbachev and remarks by a number of former Politburo members who share with him the political and personal responsibility for the remarkable shift of the Soviet foreign policy at the end of the 1980s, these statements provide a multi-voice chorus that allows us better to understand the origin and trajectory of events leading to the overall reshuffle of the world power balance by the beginning of the 1990s.

1

PREPARING THE CHANGE

We reformers dreamed of ending . . . the division between East and West, of halting the insanity of the arms race and ending the ‘Cold War’.

Aleksandr Yakovlev, ‘Gor’kaia chasha’1

Dual-Track Diplomacy

In order to understand what made possible the emergence of ‘new thinking’ as a conceptual base for Soviet foreign policy in the Gorbachev years, it is necessary to explore the political and intellectual ‘soil’ from which it arose. It is also essential to recall the basic characteristics of the ‘old political thinking’ that determined USSR behaviour on the world scene during the long years of the Cold War period. How had it influenced the international position of the USSR at the time of Gorbachev’s election to the position of General Secretary in March 1985? An analysis of this kind should identify the ideas that began to ferment within circles of the Soviet political elite several years before 1985. It would otherwise be impossible to explain the colossal change that occurred in Soviet political behaviour with the arrival of Mikhail Gorbachev, other than by the caprice of a Providence that chose him as its arm.

One of the most crucial factors paving the way for future changes in Soviet foreign policy at the end of Brezhnev’s reign was a growing feeling within Soviet society that the civilization project initiated at the time of the 1917 October Revolution had reached a stage of general exhaustion, if not fiasco. Associated with initial Bolshevik political ambition, its main message consisted initially in proposing an alternative model of societal organization founded on an ideological base imposed and supervised by the state: its protagonists were absolutely convinced that this model was destined to prevail throughout the world.

However, the initial messianic ambitions of the founding fathers of the Soviet state soon had to be revised. Not long after his death, Lenin’s hopes of unleashing the world communist revolution were rapidly reduced by his more sober and disillusioned successors to Stalin’s project of building ‘socialism in one country’.

In accordance with this evolution of ideology, the command centre of Soviet foreign policy gradually moved from the structures of the Communist International (created in March 1919) to a much more traditional state institution – the People’s Commissariat (later Ministry) for Foreign Affairs. But a con genital contradiction remained at the heart of the Soviet state. Throughout its entire history, Soviet foreign policy never abandoned the ‘double track’, constantly oscillating between support for ‘revolutionary forces’ (thus challenging the existing world order) and a quest for stability that required traditional great power behaviour and the application of realpolitik.

The innate duplicity of this policy was carefully managed by the Soviet Party-state leadership’s highest political ‘instance’ (a term usually used in Soviet bureaucratic jargon to identify the Party apparatus), and found its reflection in the parallel handling of the different aspects of foreign policy by its two ‘arms’ – mutually complementary and at the same time rival structures – the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MID) and the International Department of the Central Committee (ID), the unofficial heir of the Secretariat of the Communist International.

While the MID was charged with looking after ‘stability’ and assuring the Soviet state’s presence and position in the world ‘concert of powers’, the ID was supposed to encourage and introduce the ‘change’ needed to provide evidence of the advance of the world ‘revolutionary process’ and of the continuous shift of the world balance of power to the advantage of the USSR. These two dimensions of Soviet foreign policy, the ‘realist’ and the ‘ideological’, not only often were in competition with each other but also regularly changed places in the hierarchy of the Soviet leadership’s political priorities depending upon internal policy concerns.

The curious amalgam of ideological ambition and permanent fear within a Soviet leadership obsessed by the danger of being ‘crushed’ (a term used by Stalin) by the powerful capitalist enemy quite often provoked an ostentatiously aggressive image of the country’s foreign policy, even at times when the real intentions of its leaders (and certainly their capacities) were rather modest. As prisoners of communist dogma, the leaders of the USSR regarded the capitalist world and its member states as historic enemies with which one was obliged to coexist and sometimes even to cooperate only because of the (temporary) unfavourable balance of forces. Even the solemnly proclaimed Khrushchev policy of peaceful coexistence2 was perceived to be forced by circumstances and was intended to fill in an interval in the expectation that ultimately the capitalist rival would disappear, condemned by history in accordance with Marxist doctrine. Thus, even after initial hopes of world revolution evaporated, the ‘coexistence’ façade of USSR foreign policy directed at the Western world remained largely an expression of political tactics, while competition, confrontation and worldwide ‘continuous class struggle’ represented the real political strategy that would lead to the happy ending of History.

However, from the end of the 1960s, even the most convincing ideological arguments or persuasive citations from Marx and Lenin could no longer obscure the reality of the economic situation of the Soviet Union for the leadership of the country. Unable to nourish any hope of being able to do away with the capitalist world by military means, especially since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, they nevertheless continued to use ideological jargon stressing the ‘antagonistic conflict’ between the two systems, mostly as a means of legitimizing the totalitarian regime within Soviet society and in order to justify the state of the permanent economic disaster produced by administrative mismanagement of the economy.

In fact, having started out in the first post-revolutionary years as fundamentalist missionaries of Marxist doctrine, by the 1970s and 1980s Soviet leaders had become its prisoners. The ‘dual-track’ foreign policy of the USSR quite naturally became the programmed victim of a broadening gap between the requirements of a sterile ideological project and the reality of a changing world. More and more often obliged to deal with the aggravating internal problems of the communist regime, Soviet leaders were forced to sacrifice official strategy based on ideology, replacing it with survival tactics. And although formally the declared strategic horizon of the Soviet state’s long-term policy continued to be the predetermined victory over capitalism, this hypothetical goal virtually disappeared from the field of practical policy, passing to the sphere of propaganda, while the foreign policy sector was exclusively engaged in the daily exercise of obligatory coexistence.

After Khrushchev, who was perhaps the last sincere believer in the possible victory of the world communist cause, the ideological dimension of Soviet foreign policy was gradually reduced to rhetoric and propaganda while the conservative structure of the MID, headed by Andrei Gromyko, definitely gained the upper hand over the International Department (led by Boris Ponomarev) in the handling of foreign affairs. The MID’s new status was confirmed in 1973 by Gromyko’s elevation to the position of full member of Politburo, which demonstrated his superiority over Ponomarev, who continued to remain a candidate member.

Of course, rhetoric devoted to the continuous advance of the ‘world revolutionary process’ still could be heard in the public statements of Soviet leaders and continued to occupy an honourable place in the political reports of the General Secretary to Party congresses. Yet it was mostly meant for internal consumption and used as one of the elements of the stabilization mechanism of the system. It was increasingly evident that the actual foreign policy of the Soviet Union, although maintaining some relation to its ideological origin, had sacrificed its revolutionary ambition for the sake of great power pragmatism.

* * *

It could be argued that the institutionalized confrontation with the West became one of the basic factors assuring the survival of regime, at least until the time it reached the stage of virtual collapse at the beginning of the 1980s with a succession of deaths among its ailing top leaders.3 By this time the logic of superpower competition had so tightly chained together the military-industrial complexes of the Soviet Union and the United States that their functioning and development became de facto interconnected. Because it was rather obscurely defined, the mutually accepted formula of strategic balance offered large margins of interpretation for both sides, allowing each to present the other’s moves as a real or potential breach of the strategic equilibrium. And despite the fact that political calculations or corporate and financial interests on each side must have played an important role in the misinterpretation of the opponent’s acts and intentions, in many cases it was based on genuine mutual misgivings.

In fact it was only after the end of the Cold War, when decision-makers of both sides (with their experts and advisers) could confront and compare the mutual suspicions of those times, that the unprecedented, jointly constructed ‘hoax of the century’ was gradually unveiled. A striking incident of this kind took place when top political and military advisers of the US and the former Soviet Union met during an Oral History Conference, ‘Understanding the End of the Cold War’, that took place at Brown University, in the USA, between 7 and 10 May 1998. At this conference, President Reagan’s former National Security Adviser, Robert McFarlane, argued that the character of the defence spending of the Soviet Union in this period could hardly be justified by feelings of insecurity since ‘much of the money was going not into defensive systems but into force projection’. For the former US Ambassador to the USSR, Jack Matlock, Soviet foreign and security policy ‘did not seem to be one of retrenchment but rather expansionist with the situations in Angola, Ethiopia, South Yemen, Mozambique and especially Afghanistan providing apparent proof of it’. At the same time their Soviet colleague, Anatoli Chernyaev, maintained that since the Cuban missile crisis, any support for ‘revolutionary change’ remained largely a ‘hollow shell’, verbal ideological wrapping destined (and designed) mostly for internal consumption to support the image of the Soviet Union as an mighty superpower. ‘No one would seriously think of going to war with the West over Angola or Ethiopia.’4

For the Soviet experts of the war-time generation (Anatoli Chernyaev, Georgi Shakhnazarov, Georgi Arbatov – the former two served as principal political aides to the President while the latter played the role of an ad hoc adviser to Gorbachev), one of the explanations for a seemingly irrational ‘obsession’ with security concerns that characterized Soviet behaviour in the postwar years could be found in the ‘1941 syndrome’. This of course was the year of Hitler’s surprise attack on the Soviet Union which provoked the disorderly retreat of the Red Army, caused heavy losses among the military and the civilian population and almost resulted in the seizure of Moscow by the rapidly advancing German army. After the experience of 1941, an obsession with the danger of sudden invasion or a ‘disarming strike’ coming from the West continued to condition the political behaviour of an entire generation of Soviet leaders such as Brezhnev, Ustinov and Andropov; they were programmed to give absolute priority to the question of national defence and to accept the logic of an exhausting arms race not only with the United States but also, more or less, with the rest of the world. ‘While talking about “equal security”, it was the ambition of the Soviet leaders to match not only US capabilities but also those of America’s European allies in NATO and China as well,’ states General Viktor Starodubov.5

This kind of paranoiac policy started to produce devastating effects on the Soviet economy, which could ill afford the expense of an unlimited arms race, especially after the fall of world oil prices. It was also at this time that the entire Soviet political and economic model began to show signs of systemic crisis. As confirmed by one of the chief analysts of the former KGB, Nikolai Leonov, ‘the people from the military-industrial complex or its representatives didn’t take economics into account at all. They thought that our resources were unlimited. As if they had not been informed as to the country’s real situation.’6

After almost sixty years in power, the communist regime proved incapable of keeping its initial promises and was apparently losing its historic bet against its capitalist rival. Rejecting the very idea of any reform or modernization, the ailing Soviet Party leadership and state bureaucracy comfortably settled into the climate of ‘stagnation’, seeking to perpetuate the status quo.

The only sphere in which the decaying regime could hope to produce any sign of ‘historic dynamism’ was in the foreign policy arena, and particularly with regard to the expansion of the Soviet presence and influence in the ‘third world’. Soviet leaders preferred to rely on ‘external’ success to demonstrate the ‘historic superiority’ of the communist project for a number of reasons. First of all, it was a way of diverting the attention of the Soviet population from the rather obvious failures inside the country. Secondly, they believed that indirect confrontation with their main Western rival, the United States, in the ‘no man’s land’ of ‘third world’ countries was relatively safe and presented no risks of a dangerous military conflict between the two superpowers. Furthermore, the military-industrial complex remained the only sector of the Soviet economy that was rapidly increasing its production, was competitive on the world market and apparently supplied the political leadership with ‘cheap’, convincing arguments capable of winning the favour of a number of ‘third world’ leaders, dragging them into the Soviet sphere of influence.

Finally, Soviet Party and military bosses convinced themselves that the Western world, and above all the US, especially after the humiliating defeat in Vietnam, was being pushed into strategic retreat, leaving them a chance to gain the offensive. During the 25th Party Congress in February 1976, Leonid Brezhnev could boast that the historical ‘correlation of forces’ was shifting in favour of socialism’.7

The events that followed in the late 1970s seemed to confirm this conclusion, including the April 1978 coup staged by the radical leftist officers in Afghanistan, the June 1978 ‘antiimperialist’ coup in South Yemen, the toppling of the Shah and Khomeini’s accession to power in Iran in February 1979, and in July the victory of the Nicaraguan Sandinistas over Somoza. All these developments in the ‘third world’ could be considered to be American defeats, along with the impressive scale of the anti-nuclear movement in Western Europe that forced President Carter to abort his neutron bomb programme.

It was in these years that the Soviet military, backed by the monstrous industrial complex, gained a position of almost unrestrained domination of the political and economic life of the country, able to prevail over the Party apparatus. This process was strengthened and accelerated by two parallel events – the beginning of the rapid physical decay of the General Secretary of the Central Committee, Leonid Brezhnev, and the appointment of Dimitri Ustinov to the post of Minister of Defence in 1976. Since he had been Weapons Minister under Stalin and subsequently, putting Ustinov at the head of the Ministry of Defence combined the functions of purchaser and supplier; this had the effect of exempting the giant military-industrial complex, of which he became the sole ruler, from any political control. As confirmed by the International Department’s military expert, General Viktor Starodubov:

Ustinov brought the psychology of the producer of armaments into the strategic planning of the Defence Ministry. Since it was customary in his previous role to devise excessive, ‘reserve’, budget demands, he continued to do the same except that now he was addressing these demands not to the government or to the Party leadership but to himself. As a result there was an arms over-saturation with an unnecessary duplication of similar armaments systems, which was regarded critically even by military professionals.8

Profiting from his direct access to the ailing Brezhnev, Ustinov was guaranteed to get the formal approval of the Politburo for his demands, virtually without discussion. According to Anatoli Chernyaev, from the beginning of the 1980s

the military were pressuring our politicians so strongly that when Ustinov stood up in the Politburo to demand new billions of roubles for something, nobody dared to say anything against it. Such practice resulted in the almost routine acceptance by the Politburo of practically every demand of the military without any regard for potential political consequences or the possibility of retaliatory measures that could be taken by the other side.9

Attempting to account for this obviously bizarre situation, Andrei Gromyko (who in his role as the Minister of Foreign Affairs normally would have been responsible for preventing it) provided the following explanation to his son:

Ustinov’s presentation of new demands to the Politburo was usually preceded by a tête-à-tête consultation with Brezhnev, who almost always gave his consent to anything. After that no one would dare to object. To obtain Brezhnev’s approval, Ustinov, who knew him well, would not hesitate to profit from the fact that for the General Secretary a quantitative approach to the evaluation of military might normally would prevail over a qualitative one.10

Yet this is a rather facile version that should not be taken as the whole truth. Brezhnev’s ‘simplistic’ approach toward the complicated question of maintaining geo-strategic parity with the West would not have prevailed had it not been shared and exploited by other members of the Soviet political leadership. In addition to Ustinov, this would have included Andropov and also Gromyko himself.

The Military-Diplomatic Complex

The rapid development of the Soviet military-industrial complex was accompanied by the formation of another coalition, a ‘military-diplomatic complex’ forged between the Ministry of Defence and the MID. Certainly it was not just personal friendship that lay at the base of the close political alliance between Dimitri Ustinov and Andrei Gromyko; there was also a community of corporate interests and a shared belief that only a military build-up would assure real great power status for the Soviet Union as well as the best political bargaining position in its relations with the US. In the next decade these considerations would transform ‘Mr Nyet’ (Gromyko’s nickname given to him by his Western colleagues due to the legendary rigidity of his negotiating behaviour) into the de facto ‘Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Soviet Military’.

Each party to this alliance benefited from it. The Soviet military build-up provided the MID with necessary arguments in order forcefully to assert the USSR’s importance on the world scene. Consequently Gromyko himself was upgraded to the position of the nasty but unavoidable partner of his Western colleagues, above all the Americans. The Minister of Defence could in his turn rely on the MID to supply political justification for his military programmes. (In later years when Ustinov and afterwards Gromyko departed from the political scene, their alliance was reproduced by political complicity between their former first deputies – Marshal Sergei Akhromeev and Georgi Kornienko.)

The Gromyko–Ustinov alliance was soon reinforced by the association of the KGB Chairman, Yuri Andropov. Like Ustinov, Gromyko and Andropov were promoted to the position of full Politburo members in 1973. All three had similar views, sharing a ‘hawkish’ approach toward handling Soviet policy on the world scene.11 The constitution of this new ‘troika’ confirmed the changed balance of forces within the Politburo that began to evolve after 1975 when Brezhnev suffered the first stroke that considerably diminished his physical and intellectual capacities.12

It was at this time that the Soviet leaders’ new assertive behaviour on the international scene was exemplified in a most spectacular fashion by two defiant moves: first, the decision to replace medium range SS-4 and SS-5 missiles deployed in the European part of the USSR by the much more powerful and precise SS-20 ‘euro-missiles’, thus considerably increasing the Soviet nuclear offensive potential; next, the invasion of Afghanistan. Both initiatives were imposed on Brezhnev along with the rest of Politburo by the troika. Trying to justify these decisions in the later, ‘Gorbachev years’, Gromyko, who had been largely responsible for both actions, said the following in a kind of repentance speech during a session of the Politburo (on 20 June 1988):

In Khrushchev’s time we produced 600 nuclear bombs. Khrushchev himself from time to time asked the question: ‘When should we stop?’ Later under Brezhnev we should have taken a more reasonable position. But we remained attached to the same principle: since they [the US] are running ahead, we should do the same, as if it was a sports competition. . . . It was an evidently primitive approach but our supreme military commanders were convinced that if a war was started, we could win it. That was evidently an erroneous position, completely erroneous. And the political leadership was fully responsible for it.13

To this day, former experts of the Soviet General Staff involved in military planning as well as functionaries in the Party apparatus responsible for the defence sector continue to argue that Soviet senior army commanders as well as political leaders ‘were all convinced that the USSR was merely catching up with the USA in the strategic arms race since the Americans were always ahead of us by 20–30 per cent’.14 At the same time they claim that ever since the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, Soviet military doctrine excluded the launching of the first nuclear strike and that such an option was never considered at the highest level within the Soviet political leadership.15

While the Soviet side pointed to US supremacy over the Soviet Union in the total number of warheads, the Americans insisted that the USSR had an advantage in ‘throw-weight’ capacity and in the number of land-based strategic missiles. Each side suspected and accused the other of intending to build up a first-strike potential, while both sought any excuse to continue the upwards spiral of the arms race. The two superpowers engaged in this exercise were obviously motivated more by a common interest in preserving the status quo (including the positions of their respective military lobbies and industrial complexes) than by real defence concerns. A major distinction between the two positions lay only in the fact that the US could at least justify this strategy with the hope of bringing the Soviet economy to ruin. As for the Soviet Union, according to Anatoli Chernyaev, ‘the inner logic of self-destruction hardly required an arms race in order for the Soviet system to reach its inevitable terminal stage’.16

Thus for some top-level members of the Reagan administration, in the words of Robert McFarlane (a former Deputy National Security Adviser in 1982–3 and National Security Adviser from 1983 to 1986) aside from their strategic value, new armaments programmes represented ‘an economic argument’, since ‘the leverage that it would give us and the amount it would require you to spend would favor our side’.17 Seen from this perspective, President Reagan’s SDI (Strategic Defense Initiative) programme (often referred to as ‘Star Wars’), apart from its formally declared goal to put pressure on the Soviet leadership, compelling it to agree to more far-reaching arms reductions, was also supposed to have the effect of a ‘last straw breaking the back of the Russian camel’ by pushing the Soviet economy ‘beyond the level it could afford’,18 while its strategic role was highly hypothetical.

It fact, neither approach produced the desired result or impressed the Soviet leadership enough to make it curtail its strategic ambitions or reduce its military spending. And this despite the fact that, contrary to the United States, which was allocating roughly 6 per cent of GNP to defence, the Soviet Union, with an economy of only half the size (according to optimistic evaluations), was officially spending around 16 per cent of its GNP on military purposes.19

Reasons for such ‘politically irresponsible behavior’, in the words of Georgi Arbatov, former Director of the Institute of the USA and Canada Studies, were multiple. The most important probably were ideological: the Soviet leadership of Brezhnev’s time remained the hostage of anti-Western complexes, convinced by its own propaganda about the ‘aggressive nature of imperialism’ and its capacity to resort to military force in order to destroy the socialist community. Hence the obligation for the Soviet state and its citizens to pay whatever price necessary for its defence.20 Yet the ideological wrapping was less an explanation than a cover; there were other political and corporate motives for pursuing this line, since the Soviet regime used the bugaboo of an ‘external threat’ as an essential psychological tool in support of the totalitarian system.

In the seemingly favourable international context of the 1970s, the governing troika within the Soviet leadership saw no reason to refrain from a more ‘muscular’ foreign policy. On the diplomatic front, following the instructions of Gromyko, the Soviet MID was doing its best to clear the way for the new appetites of the Soviet military. According to one of the USSR negotiators at the US–Soviet disarmament negotiations, Oleg Grinevsky, the treaties that Soviet diplomacy was busy trying to extract from the US would ‘give us an opportunity to change the structure of the Soviet military profoundly. . . . We had the clear feeling that the US was losing the arms race and were determined to profit from it.’21

Naturally the troika of hard-liners in the Politburo advocated this policy as an ‘obligatory’ defensive move by the USSR, which was forced on Soviet policy-makers by the ‘aggressive designs’ of world imperialism and was necessary in order to protect allies and secure the status of the Soviet Union as the second world superpower. And just as additional military spending was justified by the need to ‘catch up’ with the US in the arms race, Soviet leaders viewed their own behaviour in the ‘third world’ as merely a replica of traditional American conduct.

Commenting on the spectacular shift in American policy toward the Soviet Union under Ronald Reagan at the beginning of the 1980s, Andrei Gromyko, as quoted in his son’s memoirs, believed that the international situation was ‘heating up’: ‘The US is trying to challenge the status of the Soviet Union as the great power.’ To demonstrate this, the Soviet minister repeated the mantra of official Soviet accusations, citing Reagan’s invasion of Grenada and the ‘attacks’ on Nicaragua, Ethiopia, Angola and Mozambique; the US was also attempting to undermine the solidity of the socialist community by profiting from the internal difficulties in Poland. From Anatoli Gromyko’s memoirs it can be seen that Soviet leaders of that time were quite impressed by the bellicose ideological rhetoric of the US President, whose speeches frequently included expressions such as the ‘crusade against communism’ or a promise to throw it on the ‘scrap heap of history’.22 One of the top Soviet diplomatic experts, Oleg Grinevsky, who used to meet Gromyko quite often, quotes the Soviet minister from the conversation he had with him in January 1984: ‘I think to read Reagan and his team, they are trying to destroy us and we really have to do something against it,’ said Gromyko, continuing: ‘This is fascism. There is fascism beginning in the United States.’23

Yet according to Georgi Shakhnazarov (the former deputy head of the Socialist Countries Department of the Central Committee and future political adviser to Mikhail Gorbachev), his conversations with various members of Politburo suggested that it was not the danger of US aggression against the Soviet Union that was influencing the Soviet leadership’s foreign policy of the early 1980s; rather it was the quest to enlarge Soviet control over the ‘no man’s land’ of the third world. Success here would serve not a strategic but rather an internal political purpose: ‘It would provide compensation for the shortcomings of the failing system and at the same time would offer new-found hope that the communist project could regain its historic perspective.’24

This perverse expression of a survival instinct by a dying system, wrapped in the formulas of political and ideological ‘renaissance’, had the effect of pushing the Soviet leadership to finance its ‘family’ of clients in Asia, Africa and Latin America despite the tremendous cost of economic and military support already being provided to the other ‘socialist countries’ and ‘progressive’ regimes.25