Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

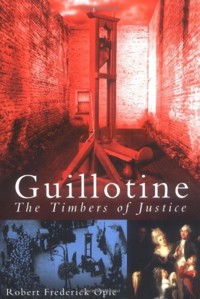

The guillotine is undoubtedly the most potent image of revolutionary France, the tool whereby a whole society was "redesigned". Yet what came to be seen as an instrument of terror was, paradoxically, introduced as the result of the humanitarian feelings of men intent on revising an ancient and barbaric penal code. Robert Frederick Opie takes the reader on a sometimes terrifying journey through the narrow streets of 18th-century Paris and beyond. Initially scorned by the revolutionary mob for being insufficiently cruel, the swift and efficient guillotine soon became the darling of the crowd, despatching as many as 60 people a day beneath its blade. But the Razor of the Nation was to remain the chosen instrument of capital punishment until the 1970s, only finally being banned in 1981. This work traces the development of the guillotine over nearly two centuries, recounting the stories of famous executions, the lives of the executioners and the scientific research into whether the head retained consciousness after it was separated from the body that continued into the 1950s. The story recounts some diabolical uses of human inventiveness, but also many touching pleas for mercy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 331

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1997

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Guillotine

The Timbers of Justice

To my wife Jean and our children, Jonathan, Laura, Drummond and Dawn

Guillotine

The Timbers of Justice

Robert Frederick Opie

First published in 2003

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © Robert Frederick Opie, 2003, 2013

The right of Robert Frederick Opie to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9605 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Chronology

Introduction

One

Death upon the Guillotine

Two

The Creation of the Guillotine

Three

The Inventor and the Builder

Four

A Simple Device

Five

Terror

Six

Justice and Retribution

Seven

The Cemetery

Eight

Dead or Alive?

Nine

The Guillotine and the Executioners

Epilogue

The Revolutionary Calendar

Appendix 1 The Pay of the Executioner

Appendix 2 The Executioners of Paris

Appendix 3 Locations of the Paris Guillotine

Appendix 4 Marie-Antoinette’s Last Letter

Bibliography

Chronology

1738

28 May: birth of Joseph-Ignace Guillotin

1757

François Damiens executed

1787

14 July: Dr Guillotin marries Marie-Louise Saugrain

1789

24 January: Estates General formally summoned by the king

4 May–20 June: parliamentary convention to decide if it should vote as a single body or as separate factions

17 June: the Third Estate (the people) adopts the new title of the National Assembly 20 June: the Assembly proclaims the Tennis Court Oath

12 July: Tension and insurrection in Paris as Necker is dismissed

14 July: The Bastille is stormed and falls to the mob 15 July: Necker is recalled to the Ministry of Finance

26 August: Declaration of the Rights of Man 5–6 October: the market women march to Versailles

9 October: reorganisation of the penal code

2 November: the Church and its property are nationalised

1790

13 February: monastic vows are outlawed

1791

2 April: Mirabeau dies

20 June: royal family flees to Varennes

14 September: the king is forced to accept the new constitution

1792

25 January: France and Austria are close to war

10 March: Dumouriez joins the government

3 March: Dr Louis devises the guillotine

15 April: the guillotine is tested on corpses

25 April: the appearance of the guillotine at the Place de Grève

13 June: Prussia declares war on France

20 June: Tuileries Palace attacked by the mob

12 August: the Tuileries are stormed, and the Swiss guard killed

10 August: the monarchy is overthrown

2–6 September: September Massacres at the prisons

21 September: Dumouriez clinches the Battle of Valmy

22 September: France becomes a Republic

1793

16 January: Louis XVI is sentenced to death

21 January: the king is executed

1 February: war declared on Britain

March 1793–June 1794: the reign of Terror, 1st phase

2 June: the fall of the Girondins

10 July: Marat is assassinated

17 July: Charlotte Corday is guillotined

27 July: Robespierre joins the Committee of Public Safety

3 October: the Girondins sent for trial

9 October: Revolutionary Government is declared

16 October: Marie-Antoinette is guillotined

31 October: the Girondins are guillotined

8 November: Madame Roland is guillotined

1794

24 March: Hébertists are guillotined

5 April: Danton and Desmoulin are guillotined

8 June: the Festival of the Supreme Being

10 June–27 July: reign of Terror, 2nd phase

27–28 July: fall and execution of Robespierre

1795

6 May: Fouquier Tinville is guillotined

1814

Dr Guillotin dies

Introduction

This book explores the darker side of human inventiveness. It is a graphic and factual account of an implement of death which helped to create and dominate a culture that is uniquely French but of interest to all. Within these pages can be heard the echoes of the falling knife, levelling out a society and dealing with the criminal classes for the ultimate benefit of a new order. From its invention in revolutionary France until the last years of the twentieth century, this nightmarish machine has stood as the archetype of swift and merciful judicial death – but was it so? The facts are more complex.

The guillotine was perhaps the most notorious and fearsome method of execution employed in ‘modern’ times. The death sentence itself is an issue that continues to engage us. In the debate about justice and punishment the subject of judicial execution refuses to go away. This book is much more than a simple compilation of facts, weaving as it does a grotesquely interesting tale of a fearful implement used by society to oppress both the guilty and the innocent.

Guillotine, n. A machine which makes a Frenchman shrug his shoulders, with good reason.

Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary, 1906

ONE

Death upon the Guillotine

For Claude Buffet and Roger Bontemps the last seconds of 27 November 1972 ebbed all too quickly into the new day. Condemned to death and held in the prison of La Santé in Paris, they were the main protagonists in a macabre drama that was yet to play its final act. At daybreak on 28 November justice required them both to meet the Grand High Executioner of the Republic of France – and the guillotine. Theirs would be the last executions by guillotine in Paris.

During a prison riot, Buffet and Bontemps attempted to escape from the Clairvaux prison. Buffet, already a convicted murderer, and his accomplice Roger Bontemps secured for themselves two hostages. Their bid for freedom was discovered but before they could be recaptured Buffet murdered both hostages, one of them a woman. Bontemps, now an accessory, found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time and with the wrong person. Though he had taken no part in the actual slayings, as Claude Buffet’s accomplice he too was found guilty of the capital crime and would face the same fate.

‘Peine de Mort’ – ‘Sentenced to Death’. The Tribunal’s judgment on Buffet and Bontemps is spoken without emotion, remorse or regret; nor is it classed as some great judicial triumph of the Establishment. It simply marks the end of a trial where the punishment must be seen to fit the crime. This is how things are, or at least how they should be! It is a simple fact of life – and of death – that all judicial systems have minor flaws and all are flexible. Every crack can be explored and the system manipulated and twisted in any direction to save the lives of those condemned by it, but the lawyers must act expeditiously for there is no time for recriminations. An appeal against the sentence must be quickly formulated to defer their clients’ fate and their early morning meeting with the executioner and the Timbers of Justice.

Perhaps some new fact may be discovered. Perhaps the conviction can be quashed on a technicality or because of irregularities. But no, not this time. The sentence is supported by public opinion and still stands. Time is fast running out for Buffet and Bontemps. All the evidence and the various controversies of the legal war waged within the courtroom have been pursued with vigour and commitment. The legal hierarchy’s obligations to the statutes of France and its people have been fulfilled, and the guilty men, potential victims of state vengeance, have been removed from court and subsequently lodged within the sombre confines of the Santé prison. The final decision either to grant a reprieve or to send the men to their deaths upon the guillotine will be in the hands of the President of the Republic of France, after which there is no appeal.

The incumbent in 1972 was President Pompidou, a man of compassion, understanding and logic. He is painfully aware that he is the last hope for the condemned men. He understands well that technology in the form of the guillotine has outlived the humane philosophy of its revolutionary inventor. His own wish is to commute the dreadful fate that now awaits the living dead. The law is the law, however, and even the President must bow before the traditions, expectations and will of the French people.

Politics now interferes with his humanitarian and individual choices. Three times previously he has used his quasi-autocratic power to waive the death sentence. In this case, however, public opinion demands justice – and the heads of the two transgressors. The prisoners must prepare to meet their fate as determined by the unilateral voice and will of society. This is the will of the people. Individual instincts and moral compulsion may compel the President to reprieve the condemned, but the powerful cry for vengeance presses him to uphold the will of the people and their judgment upon the criminals. He upholds the sentence of death for Buffet and the unfortunate Bontemps.

The small time now remaining to the condemned men can be truly likened to a hell on earth. Given no indication of the specific time for their forthcoming execution, they can only wish for time to be suspended or confined to the bright daylight hours. Condemned prisoners can only relax on a few days: no executions are carried out on Sunday and Monday mornings or on national public holidays. The executioner does no ‘work’ on these days.

The imminence of death seems to draw the violent Claude Buffet into its tight grasp. Resigned to his fate, he even begins to welcome it. Ignoring the frantic efforts made by the defence lawyers to prevent his execution, he remarks, ‘Tell everyone that Claude Buffet, the man that I am, wants to die on the guillotine. Let it be known that Claude Buffet commits suicide by the guillotine!’ In contrast, Bontemps remains silent and impassive. Still hoping for reprieve, he is painfully aware of the nearness of his own death and can only wait out the little time that remains for him.

The prison director at La Santé will receive a communication from the office of the President confirming the sentence of death. At the same time the Executioner of the Fifth Republic also receives a notification of procedure. His reads:

Dear Sir,

In the Name of the Law,

Monsieur the Executioner of the High Works is hereby ordered to take possession of the individual named Claude Buffet, condemned to the punishment of death by the Assizes Court of Paris and to proceed with the execution within the confines of the prison of La Santé on 23 November 1972 at the legally established hour of daybreak.

An identical warrant is issued for Roger Bontemps. It is to be a double execution. The President has made up his mind, and the wheels of bureaucracy are trundling along to their inevitable conclusion.

The Chief Executioner must now make his own preparations. Without formality he sends a note to his valets (assistants). They will rendezvous at the Santé prior to the execution and quietly make their nocturnal preparations. Unknown to them all, they are passing an important milestone in the history of France: the denouement of the guillotine.

The semi-assembled guillotine is stored in an airy hangar within the Santé prison. The final assembly and adjustments will be silently carried out in the prison courtyard at the place of the Cour d’Honneur. Before the final assembly, a large black awning is erected over the courtyard to prevent any unauthorised watching of the ‘National Razor’ at work. The morbid machine seems to have become a taboo subject, shunned by authority. Is the guillotine an implement of justice that justice is ashamed of?

Inside the Santé the officers and wardens of the Quartier de Haute Surveillance continuously observe the condemned prisoners. Some offer succour and the encouragement of hope – always hope, but it is hope to the hopeless. Buffet and Bontemps each has a private cell and each is allowed certain liberties within the confines of the Quartier. They may smoke all they wish, send out personal correspondence, and receive visits from the prison chaplain and their legal representatives. They are no longer compulsorily restrained with leg irons or straitjackets, as was the case quite recently. Yes of course, there is still the chance of a reprieve. The President may yet commute the death sentence. The guards remain optimistic, until with a faltering voice the officer of the watch whispers to his company, ‘It is for tomorrow – for certain.’

Just one week after the public execution of the mass murderer Eugène Weidmann at Versailles on 18 June 1939, the French government, disgusted at the behaviour of the rowdy crowds who flocked to witness such executions, passed a decree that all future executions within the city limits would take place privately in the confines of La Santé prison. This was intended to remove forever the public bloodlust aroused by the sight of the guillotine at work. Previously guillotinings had been carried out in public behind a police cordon, but it had become apparent that far from serving as a deterrent and having a salutary effect upon the crowds witnessing the feast of blood, this promoted the baser instincts of human nature and encouraged general rowdiness and bad behaviour. It was the taciturn victim of the blade who typically displayed the human dignity so lacking in the spectators.

The guillotine, robbed of its bloodthirsty and voyeuristic audience, was henceforth to be hidden from the public gaze, itself caged within the prison walls. It would become no more than a simple but efficient mechanical tool to carry out the wishes of the state on behalf of society. Nevertheless, whenever the guillotine was put to work, the execution still had to be witnessed by sane men. How strange that this act of judicial violence should have to be observed by normal peaceful men; one cannot help wondering whether they remained normal, untouched by the act.

The witnesses to the execution were designated by Article 26 of the Penal Code. This select audience comprised the following officials:

A judge of the Tribunal from the district where the execution was to take place and a clerk of the court

The presiding judge and a clerk of the trial assizes or a magistrate nominated by the first president

An officer of the public prosecutor’s office

The chief of police and gendarme escort

The prison director of La Santé

The prison doctor or medical nominee

A minister of religion

The defence counsel

It was almost 3am when a call summoned the defence counsel to La Santé. Robert Badinter, abruptly woken from sleep and troubled dreams, now entered the living nightmare. Dressing hastily, he was brought along the quiet Parisian roads towards the prison. The rest of France would eventually awake to hear the news of the execution. Robert Badinter arrived at the prison and was taken towards the Quartier de Haute Surveillance. Entering the prison courtyard, he was confronted by his first sight of the guillotine, sometimes called ‘the Widow’ since all who lay with her were damned. It was fully prepared and waiting. The servants of the machine had expertly and silently completed their preparations and were nowhere to be seen; they had withdrawn to a room within the prison to await the arrival of the condemned.

An eerie silence prevails before the final ritual begins. In the dim light the machine seems almost alive, poised and waiting impatiently to embrace its fresh victims. Covered from prying eyes by the large black awning erected over the courtyard, it stands so very tall and slender, the distance between the uprights being no more than 18 inches. Its symmetrical bearing, although sinister and fearful, exerted an almost hypnotic influence over all who dared to study and observe it. Like a Medusa, it seemed to stare back with a narcotic power capable of turning the living observer to stone. Standing near the guillotine, one is in absolute awe of it.

It transfixed Robert Badinter’s gaze and would not release him from its grasp. The compact base of the apparatus, though small to the eye, complemented the scale of the machine’s malevolent and sadistic beauty. The bascule stood vertically and parallel with the uprights and seemed to point to the high nest where the gleaming blade, sharper than a sabre, lay in waiting. The heavy blade’s weight was supported by a pincer-like device anchored to the crossbar holding tightly a spike that protruded from the mouton.

The condemned men endure their uneasy sleep, troubled by hideous dreams, and unaware that the guillotine has been assembled and that the witnesses have already congregated within the Santé. The ever-vigilant prison officers suddenly stand to attention as the prison director appears; in response he simply gestures to his staff. There is no need for words; all those present anticipate the director’s instructions. The strain lends a waxy pallor to their complexions, a pallor that is accentuated by the artificial lighting. The executioner and his assistants await the appearance of the condemned in a room close to the courtyard for the final ‘toilette du condamné’. It is then only a short walk to the guillotine. Without knowing why, Roger Bontemps is to be the first.

The wardens approaching the cell have slipped off their shoes. Even in the last few seconds they must not alert the prisoners, who are left undisturbed in their cells until the very last moment. Bontemps will be pounced upon before he realises what is happening. The door opens. The wardens enter rapidly, well drilled in the required manoeuvres. They firmly seize hold of Roger Bontemps. Sleepy and unaware, he is not sure whether what is happening is still a part of his dreams. His pulse quickens as he anxiously searches for a sympathetic face among the men around him, but there is nothing to comfort him or allay his worst fears; it is not a dream. The tension in his muscles gives way to a strange and strained acceptance of what is now inevitable. The final moment has come. The prison director stands before him and offers the traditional words: ‘The President has rejected your appeal; be brave!’

Then Bontemps and his escort, preceded by the director, leave the dim cell; the ritual of the guillotine has now begun. Claude Buffet will follow shortly – the executions will be carried out consecutively. Strangely, there is no great hurry now. The bureaucratic wheels turn slowly, even before an execution; there are still formalities which have to be observed. The condemned move from room to room in turn. Each will be given back the clothes he wore on arrival at the prison and if they so desire they can take time to write a letter, perhaps to a loved one or a friend. For each there will be Mass and Confession; finally they will stand before the director of the prison for the very last time. The director produces each man’s prison record and signs it; the condemned man also signs it. Everything has now been officially and correctly carried out. The final statement on the record reads: ‘Handed over to the Executioner of the High Works for carrying out of sentence.’

Like Pontius Pilate, the state has washed its hands of the condemned person. He has been given to the executioner, and is now his sole property. The toilette du condamné now follows. The hair is cut from the nape of the neck and the shirt collar removed with a large pair of scissors so that the shirt is left lying loose about the shoulders. The feel of the cold scissors on the back of the neck sends a shudder through the body, anticipating the feel of the guillotine’s blade.

Robert Badinter has been very attentive, observing the hideous ritual as it slowly progresses through the prison precincts. They are now very close to the exit leading to the courtyard and death. It seems as if the victims of the state are taking part in a theatrical farce. They are offered large mugs of Cognac to help steady their nerves – the last human act before they enter the arena of death. Cords have already been cut to the appropriate lengths and are used to bind the arms and the feet. Badinter embraces Bontemps for the last time. Neither can speak. Emotion has overwhelmed them both, for what is there now to say but farewell? Is this ritual deliberately symbolic? A representation seemingly reminiscent of Christ’s last moments before the cross as He was taken from staging post to staging post before the long climb to Golgotha? The symbolism is imprinted in Robert Badinter’s mind.

Everything now seems to be ready. The prisoner, hampered by his leg cords, is assisted and supported by the executioner’s assistants. They take him under the arms and speedily usher him into the courtyard towards the waiting guillotine. The witnesses, discreetly distant, follow at such a rapid pace that they seem to be almost running. Robert Badinter finds it hard to tell who is now the criminal and who the victim of this appalling night. The new killers, ashamed of their duties, wear a fixed expression, appearing to be masked as in a Greek tragedy.

As if in a trance Robert Badinter watches Bontemps’s last moments. On reaching the guillotine, the valets directly behind him forcefully thrust him against the bascule. The weight of this living corpse falling on to the plank tips the mechanism down horizontally. The two assistants speedily push the bascule forward on its roller into the jaws of the guillotine. Bontemps’s head now lies on the lower block of the lunette, his neck between the uprights. Another assistant on the head side of the apparatus swiftly lowers the top section of the ‘little moon’ on to the victim’s nape. His ears are grasped and, like an animal in a slaughterhouse, his head is pulled forward in the lunette. A click is heard as the executioner releases a lever. The pincer device attached to the crossbar releases the blade assembly. In less than the blink of an eye it is down. The Widow has devoured her prey.

Robert Badinter heard the hollow sound made by metal sliding in metal, and the awful crashing sound as the heavy mouton and blade slammed home, the buffers at the base of the machine absorbing the impact. The blade slices with ease through the neck of Roger Bontemps. It has all happened in the space of a second. The decapitated head falls forcefully into a metal receptacle. The shuddering body, still bound by the cords, is thrown into a makeshift wicker coffin placed at the side of the apparatus. The bloody head, its eyes staring widely, is lifted from the receptacle by the ears and placed beside the body in the coffin. The executioner and his assistants, good workmen all, are throwing buckets of water over the housed blade and the courtyard. Bloodsoaked sawdust is shovelled into the wicker coffin. They wash their hands and arms clean of blood – so much blood! The guillotine is reset and all is again in readiness. The same horrific scenario is repeated and in half a minute or so Buffet is also dead. May Justice bless the guillotine and its servants for, according to the Law, Justice has prevailed. It is daylight now, and the Cour d’Honneur is empty; there remains no sign of the night’s tragedy. The guillotine has been carefully dismantled and taken away to rejoin its sister machine. Satiated with the blood of many years, they rest quietly in the confines of an airy hangar.

Could any civilised and compassionate society look upon these events and not be repulsed by the sight, sounds and smell of such an ordeal? Was the continued use of the guillotine truly representative of justice and equality, or was there a better way? A new way to replace this sickening ritual, secretly and scurrilously carried out in the name of the law while all is cloaked in the anonymity of darkness?

After witnessing the deaths of his clients, Robert Badinter finally left the Santé prison. He too suffered at the hands of the guillotine and now bleeds with emotion from the wounds of trauma and despair, but it is in such great despair that the enlightened man can see something positive. Out of this terrible defeat he would grasp a distant victory and it would be his victory over the guillotine. He would fight fire with fire and adopt the mask of executioner, except that his target would be the guillotine itself. Along with other members of the legal profession, Robert Badinter would become a driving force behind the movement to lay the antiquated and barbaric machine in its own grave. It was a cause that Badinter took very seriously and which complemented his researches into justice in the revolutionary period and his wide-ranging interests in countering all forms of oppression and injustice.

How strange that the guillotine, an object of damnation, was created for all the right reasons: to put an end to the inequality of death prescribed by the state. To end the vile tortures, burnings and other pagan forms of execution, handed out and measured according to social class and status. The guillotine was the embodiment of equality in eighteenth-century France, but values change over time, sometimes for the better, sometimes not. In twentieth-century France revolutionary thinking is different, and its object must be the nobler hopes and aspirations of an enlightened people.

Agreement can never be unanimous on the punishment appropriate for certain terrible crimes. The ‘National Razor’ – one of the guillotine’s many nicknames – has consumed the murderer, the parricide, the anarchist, those whose politics fell foul of the state and many others; and yet through successive generations they still remain with us. They will always remain with us, human nature being what it is. Perhaps a new way had to be found. Liberty, Equality, Fraternity – and now Enlightenment. Just as the guillotine was the product of an earlier, rather equivocal enlightenment, the machine itself now had to be abandoned – it had had its day.

The guillotine was never again used in Paris following the double execution of Bontemps and Buffet. The machine did have four further feasts in provincial France, the more graceful of the two remaining machines being used each time. Its older and more heavily constructed sister apparatus never left its home within the Santé prison. The final execution took place at Douai in 1977, and the last victim, a child killer, asked for the forgiveness of France before his death. As it happened, he was not French but an impoverished and wretched immigrant, and France did not forgive him. Some would suggest, however, that now the guillotine was being used selectively and was even discriminatory in its choice of victims. An immigrant murderer of low social standing was far more likely to be executed than an equivalent French citizen from the higher echelons of society.

The issue of capital punishment, its morality and its deterrent value, always arouses strong emotion in debate. As a gross generalisation, though the opinion of the people may call for its return, it is unlikely that any political party in western Europe would ever reinstate it. Indeed such a reinstatement may even prove to be illegal within the ambit of authority of the European supreme courts. Throughout its lifetime the guillotine represented the ultimate method of ridding ourselves of our homicidal counterparts. Swift and mechanical, it proved to be extremely effective in dispatching even large numbers of those who were no longer wanted on the voyage! The trouble with the guillotine was that it was too efficient. It was loved and hated, loathed and admired. The love–hate relationship between society and the Timbers of Justice flourished; anyone who had seen the machine, provided it was not in use, could not help but be impressed by it. Its form, its lofty and geometric lines are pleasing to the eye. Its purpose, intentions and function exude a hypnotic power. The guillotine had style and was firmly entrenched in French culture.

By 1981 Robert Badinter had progressed in his career. He was filled with commitment and possessed the admirable quality of tenacity. In that year he became France’s Minister of Justice and proposed a motion requesting the National Assembly to abolish the death penalty in France, thus completing the work begun in 1829 when Victor Hugo published his Last Day of a Condemned Man. The assembly and senate of the socialist government of France accepted the motion overwhelmingly. Badinter had triumphed, nine years after Roger Bontemps and Claude Buffet had been tipped into the abyss. After 188 years the rule of the guillotine was over, and the sound of its falling blade was silenced for ever. Vive la France!

TWO

The Creation of the Guillotine

In the calm before the storm, the ancien régime of France was apprehensive and disturbed. King Louis XVI and his wife Queen Marie-Antoinette may well have shared some of this disquiet, but were unaware of their destiny. They and many of their loved ones were doomed to die on a killing machine as the proletariat cheered and welcomed the affirmation of a new order.

Devised during the French Revolution, the guillotine, strangely enough, was not the product of vile or vengeful minds but rather was the idiosyncratic result of the egalitarian tendencies of learned men whose main concern lay in the notion of equality for all and the concept of man’s humanity to man. The guillotine’s insatiable appetite, driven on by the violent upheavals of a nation caught up in a radical change of direction, engineered its misuse. It could be argued that this assisted the growth of the modern ideology of man’s inhumanity to man, since the machine continued to be used well into the twentieth century. Astonishingly, history shows that the number of deaths upon the guillotine in future years would far outnumber those during the revolutionary years in France, including the Reign of Terror. From its conception the guillotine was seen to be a highly efficient tool. Indeed, its sinister efficiency and sheer presence might even be thought to have created the demand for victims. A supply was duly obtained.

The French Revolution was eventually overtaken by the traumatic events it inspired and was subverted in its turn. In the outside world, its symbolic badge – the Timbers of Justice – lived on and prevailed. The Revolution in France liberated radical philosophical ideas, provoking strong debate and fiery oratory. This was the new platform for the politicians and thinkers of the day. ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’ were to be the heralds of a new era, glorified by freedom of speech and the establishment of the rights of man; supported by the redistribution of wealth it was to redefine the role of the monarchy and the Church.

But the reality turned out to be rather different as the new breed of men fell foul of their own policies, hopelessly tangled in their philanthropic values and political beliefs. As Rouget de Lisle’s La Marseillaise echoed through the political chambers, the many and various groups turned against one another. Jealousy, fear and intrigue were rife, and the secret police were kept busy; prisons were overflowing as the law caught in its web guilty and innocent alike. Underpinning all this was the fear of outside intervention as foreign powers watched and waited, like vultures round a wounded animal. Government degenerated into rule by denunciation, and instead of being protected by the law, individuals were greatly at risk from it: no one was safe. But at last, out of these turbulent times emerged the truly great and prosperous nation of France.

As the pace of the Revolution gained momentum, many of its gladiators were to perish, unable to hold on as the revolutionary wheel spun faster and faster, culminating in the Reign of Terror. The Revolution would eventually turn on the principal players and destroy them all with its Timbers of Justice: a king with no authority, a despised queen, Georges Danton the voice of the people, cynical Mirabeau, the brave Lafayette, the unscrupulous Orléans, vain Bailly, pedantic Necker, those tigers of the revolutionary jungle Robespierre and St-Just, and thousands more.

At the heart of the political turbulence was the city of Paris, its people then near starvation, its politicians desperately trying to cope with unrest and revolt in provincial France and the escalating aggression elsewhere in Europe. Casting its long thin shadow over all was the inescapable spectre of the guillotine, the only certainty in France’s turmoil. It encompassed royalty, aristocrats, politicians and peasants alike, beckoning them on with its blood-drenched arms. Out of the dramatic turbulence of the Revolution came the kind and philanthropic humanitarian Dr Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, whose reputation would be forever tainted by the infamous device that bore his name.

Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was born in Saintes on 28 May 1738, the ninth of twelve children. His birth was premature, precipitated by his mother’s chance witnessing of a distressing public execution. The penal code in the pre-guillotine era allowed for executions to be carried out by various methods according to the condemned man’s place within the social hierarchy. For members of the aristocracy death might be painful but it was meant to be quick and relatively merciful. For the plebeian class it was something entirely different, often protracted, agonising and grotesque. Such hideous executions were not specific to French culture – they were endemic throughout the whole of the ‘civilised’ world. The penalty exacted by the state for capital offences had changed little over the centuries and feudal punishment was severe and often horrific. Before the victim received the coup de grâce, he or she was almost invariably tortured in the most barbaric fashion. This torture, known as ‘the Question’, was abolished by King Louis XVI not long before the Revolution.

The penal code of pre-revolutionary France listed more than one hundred capital offences, and criminals could be put to death in various ways. Beheading with a broadsword or an axe was reserved for the aristocracy, the skills of the executioner being of paramount importance. Any lack of expertise could result in a protracted and often cruel death. For the lower classes of society, the gallows waited. This effectively resulted in slow strangulation, perhaps lasting some fifteen or twenty minutes. (The neck-breaking techniques developed by the latter-day hangmen of England had not yet been invented.) The murderer, highwayman or bandit could expect to be broken on the wheel, an agonising death. A hefty bribe to the executioner might speed up the process but more often than not it was a long-drawn-out and hideous death. Religious heretics of the day, magicians and sorcerers were burned alive. The more merciful of the executioners would strangle the victim before the flames of the pyre began to burn the living flesh.

For an attack upon the king’s majesty, would-be plotters and assassins faced a horrifying fate: they were hanged, drawn and quartered. The misguided regicide François Damiens (1714–57) made a somewhat ineffectual attack upon Louis XV with a penknife, which resulted in a scratch on the royal arm. Eight weeks of ‘the Question’ established that Damiens – a religious fanatic – had acted impulsively and alone. His assault upon the king was not part of any conspiracy aimed at destroying the monarchy. Stoically enduring the subsequent torture, Damiens was led from his internment within the Conciergerie prison, grey haired and almost insane. This pitiful remnant of humanity was to be put to death without mercy. He was to be taken to a place of execution, where, according to the court’s judgment:

on a scaffold that will be erected there, [Damiens’s] flesh will be torn from his breast, arms, thighs and calves with red-hot pincers, his right hand, holding the knife with which he committed the said parricide, burnt with sulphur, and, on those places where the flesh will be torn away, poured molten lead, boiling oil, burning resin, wax and sulphur melted together and then his body drawn and quartered by four horses and his limbs and body consumed by fire, reduced to ashes and the ashes thrown to the wind. (Pièces originales et procédures du procès fait à Robert-François Damiens)

The executioner, perhaps ashamed of the cruelty meted out to the tragic Damiens, loosened the sinews and joints of his pathetic victim with a sharp knife so that he could be torn apart more easily. As darkness fell, mercifully masking the appalling scene of mutilation and death, the atrocious death of François Damiens, so reminiscent of the suffering of early Christian martyrs, was hidden from human sight – but not from history.

Some two to three hundred felons succumbed to execution in its various forms each year. It was Madame Guillotin’s misfortune, on 27 May 1738, while in the late stages of pregnancy, to witness by sheer chance the screaming agonies of one of life’s unfortunates who had been condemned to death by being broken on the wheel. The barbarity of the occasion made her collapse, and her ninth child, Joseph-Ignace, was somewhat prematurely ushered into the world the very next day.

The second half of the eighteenth century was an era of social upheaval and radical change. Science was blossoming and medicine was making giant strides. More dangerously, it was also a time of free thought and expression – a potent force and one that could prove lethal to a fossilised and entrenched government desperate to maintain the status quo. But for some of the most advanced thinkers, the greatest danger was to themselves and their disciples. When change occurs too quickly and freedom of speech is just too liberal, it can change and reshape the ideas and functions of society and thus promote anarchy. Those outspoken philosophes in the political sphere walked a tightrope over a very deep chasm into which they might fall at any time. Those incarcerated within the walls of the fortress called the Bastille could find no audience and any voices they heard were merely the echoes of their own. Charles Dickens characterised it with pinpoint accuracy: ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair . . .’

The late François Damiens’s moment of regicidal insanity might have been inspired by – and so might compromise – the Jesuits and other religious factions, or better still those stalwarts of sedition, the philosophes