18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

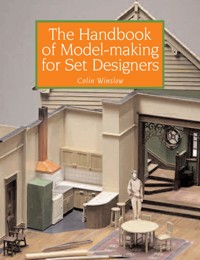

The Handbook of Model-making for Set Designers describes the entire process of making scale models for stage sets, from the most basic cutting and assembling methods to more advanced skills, including painting, texturing and finishing techniques, and useful hints on presenting the completed model. Many drawings and colour photographs of the writer's own work illustrate the text. Some state-of-the-art computerized techniques are described here for the first time in a book of this kind, including many ways in which digital techniques can be used in combination with the more traditional methods to enhance the model-maker's work. This book will be of use not only to theatre designers, but to anyone with an interest in scale models of any kind. The book covers; tools and materials; painting and texturing; architectural models; people, trees and organic elements; moving parts; furniture and dressings. Superbly illustrated with 200 colour photographs and drawings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 318

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The Handbook of Model-making for Set Designers

The Handbook of Model-making for Set Designers

Colin Winslow

THE CROWOOD PRESS

This book is dedicated to all the students who have attended my classes at Northbrook College, Worthing; Mountview Theatre School, London; The University of Middlesex, London; The School of the Science of Acting, London; The Rose Bruford College, Sidcup; The Department of Drama at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

First published in 2008 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Colin Winslow 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 054 6

PHOTO CREDITS

Holly Beck, Bath; Ellis Bros., Edmonton, Canada; J. Van Ens, The Edmonton Model Railway Association, Alberta, Canada; Barry Hamilton, Mold, North Wales; Josiah Hiemstra, Edmonton, Canada; Craig Le Blanc, Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Canada; Peter Ruthven Hall, The Society of British Theatre Designers; Hojin Kim, Edmonton, Canada; The Sandra Guberman Library, Department of Drama, University of Alberta, Canada; Andrew Stocker, Customer Liaison Manager, Bristol Old Vic. All other photographs and illustrations are by the author or in his collection. All set and costume designs are by the author, unless otherwise stated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

So many people have offered such unstinting help and encouragement with this volume that I would be unable to rest comfortably without expressing my genuine gratitude to some of them at least, particularly the following: Lee Livingstone, friend and colleague, for patiently reading and correcting drafts, and her always shrewd advice; Guido Tondino and Victoria Zimski for their constant encouragement, support and friendship; Jan Selman, Chair of the Department of Drama at the University of Alberta for employment, support and friendship; Chris Want, Denise Thornton and Mel Geary for their friendly and enthusiastic help with digital technologies; Robert Shannon for sharing his office and bringing Captain Siborne’s amazing model to my attention; Craig Le Blanc for supplying the photograph of the laser cutter at the Faculty of Environmental Design at the University of Calgary; Andrew Stocker, Customer Liaison Manager at Bristol Old Vic, for the photograph of the model of stage machinery in that theatre’s foyer; Mark Johnson of the Edmonton Model Railway Association for the photograph of their impressive layout; Karon Butler of Dolls House Miniatures of Bath for the pictures of the Bath Circus dolls house; Josiah Hiemstra, for patiently taking many special photographs for this book, and losing his camera in the process; Robin Ramsdale, friend and reluctant hand-model. Finally, very special thanks to all my students, in Britain and in Canada, who have taught me so much, and to whom this book is dedicated.

CONTENTS

1

Introduction

2

Various Types of Set Model

3

Tools and Materials

4

Basic Techniques

5

Architectural Techniques

6

Painting and Texturing

7

Furniture and Dressings

8

Flown Scenery and Moving Parts

9

People, Trees and Other Organic Elements

10

Digital Techniques

11

Displaying and Presenting the Model

12

Constructing a Set Model Step by Step

Bibliography

Index

A stylish dolls’ house designed by Holly Beck, based on one of the famous Circus houses in Bath. Available from Dolls House Miniatures of Bath. PHOTO: HOLLY BECK

1 INTRODUCTION

‘When we mean to build,

We first survey the plot, then draw the model;

And when we see the figure of the house,

Then we must rate the cost of the erection;

Which if we find outweighs ability,

What do we then but draw anew the model …’

Lord Bardolph in Henry IV, Part 2 (1597) Act 1, scene 3, by William Shakespeare

There is magic in a scale model, and the more detailed, the more accurate, the more true-to-life the model, the greater the magic it contains. We recognize this magic as children when we play with our dolls’ houses or toy trains. A child’s world has strict limitations, and it is hard to appreciate the concept of ‘house’ or ‘train’ when one’s world is too small to encompass the object as a whole. However, through a model, children can explore the world about them without the intimidation of being considerably smaller in size than the adults the world is designed for.

For those of us who became fascinated by the theatre at an early age, a toy stage will always hold a very special magic: it allows us to experiment with exciting but impractical theatrical notions that we know could never become reality in a full scale production, but when combined with the creative imagination of a child, those miniature shows hold an enchantment of a kind rarely found in the real world. Limitations of mere size are far easier to cope with than the restrictions imposed upon us by considerations of budgets, safety, time, and the multitude of technicalities we have to take into account as set designers, and we can also ignore those stylistic restrictions we must impose upon ourselves in our grown-up, real-life design work. In our toy theatres, our imagination is given free range.

Ancient civilizations appreciated the magic contained in miniatures, as the beautiful models excavated from tombs clearly demonstrate. Egyptian tombs held scale-model boats, chariots and miniature rooms, elaborately furnished for use in the after-life, and the tombs of Chinese potentates have contained whole armies in miniature. The fact that these objects are far too small to be of any practical use to their owners is ignored, and the scaled-down objects are seen as an adequate substitute for reality.

The elegant entrance hall of the Bath Circus dolls’ house. PHOTO: HOLLY BECK

The scale models we build as set designers are, of course, quite different in purpose, but also contain a certain element of magic, for they constitute a prediction of the future, demonstrating a wish or desire for some future creation. Sometimes the creation turns out to be glorious, and sometimes (less often, we hope) it is doomed to failure. However, like all theatrical productions, once the creative act is complete, it has served its purpose and becomes redundant: hence the sad, dusty and battered models sometimes found quietly mouldering on the topmost shelves in theatre workshops, but still containing, under the dust, the shadowy record of a creative act.

In fact, the theatre is in itself a model of a kind, for the performances that take place upon its stage are not reality, but, however far removed, constitute a representation of some aspects of life itself: it is a model for Life. Many believe there are yet deeper layers in the model, that the world we inhabit is merely a model of some divine or cosmic after-life; or even, as Douglas Adams demonstrated in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, merely a huge model built by mice to work out the answer to the Meaning of Life, the Universe and Everything.

Occasionally, scale models attain a remarkable degree of notoriety: whenever an architect’s model for a new building is exhibited there is frequently a cry of public outrage against the proposed design. In the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral we can still see the ‘Great Model’ that Wren had constructed to demonstrate his concept for the new cathedral – but Sir Christopher Wren’s beautiful model was considered deeply shocking at the time, and he had to resort to a degree of subterfuge to persuade the Church hierarchy of his day to accept his controversial design; and in the National Army Museum in Chelsea, visitors today can still admire a vast model of the Battle of Waterloo covering over 37sq m (about 400sq ft) and including 75,000 finely modelled and painted tin soldiers – but at the time it so offended the Duke of Wellington, because it demonstrated that he had not, in fact, won the battle single-handedly as he had claimed, that it had to be severely altered to appease the irate Duke. Its builder, Captain William Siborne (1797–1849), having devoted years of work to researching and constructing the model, eventually died an impoverished and broken man. A model, it seems, can also contain the power to corrupt.

Details of the impressive model railway layout of the Edmonton Model Railway Association in Alberta, Canada. PHOTO: J. VAN ENS

The Neptune, a hand-painted Victorian toy theatre from Benjamin Pollock, still holds a special charm, in spite of its disregard for technicalities such as scale and sightlines that concern the set designer today.

Sir Christopher Wren’s ‘Great Model’ for St Paul’s Cathedral was built from oak in 1673–74, at a scale of 1:24. It is 6m (about 20ft) long, high enough for a man to stand up inside, and cost as much as an average London house of its day. It was constructed with superb joinery and exquisitely worked cherubs’ heads, flowers and festoons. Originally some of the detail was gilded, and the parapets were surmounted with tiny statues, which were probably Wren’s first commission to Grinling Gibbons, the master craftsman who produced much of the fine carving to be seen in the building today.

PHOTO BY KIND PERMISSION OF THE DEAN AND CHAPTER, ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL

A set model, however, does not usually corrupt anyone, although it may occasionally shock, for despite its inherent charm, it is a model with a practical purpose. It is not a toy, and unless it eventually ends up in some kind of retrospective exhibition, it will be seen by only a very small group of people. In fact it has several purposes, in that a large part of a designer’s work consists in communicating creative concepts to the team of people working on the show in production. The director, actors, stage management, set builders, property departments, costume and lighting designers need to be familiarized with the set designer’s intentions long before they become concrete reality, and sheets of technical drawings, which need some skill to interpret, can never hold all the information the designer has to communicate to all these various departments, however detailed they may be.

This is where the scale model becomes preeminent. A glance at the model will show precisely what the designer has in mind, including many important aspects that cannot be indicated in the drawings, such as colour and texture. Anyone looking at the model will appreciate those aspects that affect his or her particular interest: the actor will note any steps or levels that he will have to negotiate in performance; the builder will notice any parts that might be tricky to construct or support; the costume designer will register the colours that the costumes will need to interact with on stage; and the lighting designer will note implied light sources and those places that might be difficult to light. Some directors like to use the model to plan their entire production in advance; others prefer to work more spontaneously, but will nonetheless use the model to keep a clear image of the set in their mind during the rehearsal process. The scale model is therefore an invaluable tool for all these people, and is generally considered indispensable to any production.

The lines quoted at the head of this chapter seem to indicate that Shakespeare appreciated the value of a model, although Lord Bardolph is not talking about the type of model discussed here – and in fact Shakespeare had no need of set models, because the Elizabethan playhouses provided him with an acting space which, through the power of language and his audiences’ imagination, was perfectly adequate for any production in the players’ repertoire. The more elegant and sophisticated performances at Court or in the banqueting halls of ducal palaces, however, presented some problems. Here, performances were required to take place in rooms with distinguishing architectural features such as fireplaces, doors and windows, and containing an assortment of domestic furnishings, and it would have been difficult for an audience to visualize, say, a wood near Athens or a stormy sea while looking at oakpanelled walls hung with family portraits.

Captain Siborne’s huge model of the Battle of Waterloo created a sensation when exhibited at the Egyptian Hall in 1838, but the Duke of Wellington objected to the inclusion of a large number of Prussian soldiers because it gave the (quite correct) impression that he had received a great deal of assistance from that quarter. Pressure was brought to bear upon the unfortunate Captain Siborne, and he was obliged to remove thousands of exquisitely detailed, 1cm (about ½in) high Prussian soldiers to preserve the Iron Duke’s reputation of being solely responsible for the great victory.

Design by the architect and scene designer John Webb (1611–72) for Sir William Davenant’s opera The Siege of Rhodes in 1661.

PHOTO: THE SANDRA FAYE GUBERMAN LIBRARY

The solution was to command the Court architects and painters to design spaces especially for performance. Many of the royal palaces of Europe contained extremely spectacular theatres, and travellers described the elaborate scenic effects they had seen on their journeys. Elizabeth I had been comparatively economical in her entertainments at court, but her successor James I – or more particularly, his queen, Anne of Denmark – was prepared to expend huge amounts of money on ever more spectacular productions. The celebrated English architect and designer Inigo Jones (1573–1652) found that one of his principal functions at court was to design stages, machinery, scenery and costumes for elaborate masques of a kind that were never encountered in the popular theatres on the south bank of the Thames, nor even in the private theatres of Blackfriars or Whitefriars.

Inigo Jones greatly admired the skilful use of perspective that he had seen in Italy, and he introduced many of these effects into his work at the court of King James with spectacular success. However, the court painters used the tools and techniques with which they were already familiar to produce their scenes; and their scenery, painted on large canvas-covered wooden frames that were bigger versions of the kind they used for portraiture, was seen literally as a mere background to the action, and there was little or no interaction between the performers and the scenery behind them. Even the machines designed to lower gods from painted clouds or to sink through the floor into a painted Hell, were decorated with flat profiled and painted scenic panels.

Usually, painters would produce a sketch of some kind before working on a scene at full size, and many designs still exist that have a superimposed grid of pencil lines, clearly indicating that they were intended to be enlarged. It is a technique still used by scene painters today. It was a small step, therefore, to cut away the surrounding paper or card from the painted designs and assemble the several pieces to produce a simple model of the complete scene.

We know that as long ago as the early sixteenth century, the Italian painter and architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554) was making models of the fantastic machines he designed for the theatre – but his scenery still consisted basically of flat painted panels, supplemented by painted wing pieces. It was probably the innovative painter and stage designer Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740–1812), engaged by the actor/manager David Garrick (1717–79) to design scenery for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, who first used set models in the way we do today.

De Loutherbourg introduced a remarkable realism to the stage by the use of detailed cut-out set pieces such as rocks, mountains, houses, trees and fences; these often concealed rostra, steps or ramps behind them, so that actors could ascend the painted mountains and appear at the upper windows or on the balconies of the painted houses, thus interacting with the scenery instead of merely performing in front of it. He also introduced elaborate new lighting, with mechanically operated filters made from coloured silks to create special effects such as sunsets, moonlight, fires and volcanoes. Thus his sets were no longer solely dependent upon the skill of scene painters, and the combination of built pieces, transparencies and lighting tricks must have made the creation of scale models essential to convey the total effect of his innovative ideas. De Loutherbourg may be considered to be the first theatre designer in the modern sense.

Design for a painted cut-out piece from a prison scene by de Loutherbourg.

PHOTO: THE SANDRA FAYE GUBERMAN LIBRARY

As stage sets became more and more integrated into the action of the productions they contained, and three-dimensional built scenery replaced the flat, painted backcloths and wings, scale models came to be viewed as an essential tool in the production process throughout the twentieth century. The trompe l’oeil techniques of previous ages were generally abandoned as plays were written that seemed to require a new kind of realism; box sets now suggested real rooms with real furniture, and three-dimensional architectural features such as built mouldings and panelling. Scale models were needed as an aid to designers and directors in establishing a precise arrangement of furniture and props appropriate to each production.

In the early years of the twentieth century, the more innovative designers and directors such as Adolph Appia (1862–1925), Edward Gordon Craig (1872–1966), and Vsevolod Emilievich Meyerhold (1874–1940) attempted to introduce a completely new type of theatrical performance that was more dependent upon the visual aspects than the textual, the actor becoming merely a moving part of the total stage picture. Their influence was far more extensive than the few productions they designed, and by the middle of the century, stage designers were expected to contribute to the conceptual aspects of a production to a much greater degree than ever before.

Detail of the huge wooden model built by Edward Gordon Craig for Bach’s St. Matthew Passion.

PHOTO: THE SANDRA FAYE GUBERMAN LIBRARY

It was realized that stage scenery could go far beyond merely creating a theatrical version of reality, and designers began to employ an infinite range of conceptual ideas using many innovative techniques and new materials. It was no longer taken for granted that a stage set should resemble the physical location of the action as described in the text, and the scale model came to be seen as an essential tool to demonstrate the design concept. This meant that designers were expected either to develop model-making skills alongside their traditional rendering and drafting techniques, or to employ skilled model makers to do the work for them. Theatre design courses now usually include model-making in their syllabi, and students are expected to spend many hours honing their skills.

To many designers, the time spent building a model is the most pleasurable part of their work. It is a slow, usually solitary process that allows one to familiarize oneself with all the finer details of a design as it takes shape in miniature form; and simultaneously it offers a sometimes rare opportunity to listen to favourite music and reflect upon life in general. It is a time to aspire to sainthood.

The set for What the Butler Saw being used in the paint shop as reference for the cloud-painted ceiling.

2 VARIOUS TYPESOF SET MODEL

The set models with which we are most familiar are those beautifully constructed presentation models we sometimes see in exhibitions or as photographs in books on stage design. However, the designer will often make other models that may not look so impressive, and are usually seen by only one or two people closely involved with the production process – and sometimes only by the designer himself. The presentation model takes a very long time to construct so cannot be seen as an experimental tool, to be continually rebuilt and readjusted as an aid to the creation of a satisfactory design scheme. To avoid much wasted time and effort the design should be already established and approved before beginning the lengthy process of building the final model. Here we confront a typical ‘chicken or egg’ situation: how can the design be approved without the most effective method of demonstrating the designer’s intentions? On the other hand, can we be expected to devote hours of work to a model that may need to be severely altered, or even abandoned altogether?

CONCEPTUAL MODELS

Sometimes a designer will build simple models as an aid to developing conceptual ideas. These models are very different from the finished presentation model, as they are rarely seen by anyone but the designer and the director, and little time is spent in their construction. They are usually temporary in nature, often involving little more than arranging a group of objects and some scrap card or paper that happens to be to hand at the time. They are often a type of three-dimensional collage.

The designer may find it useful to photograph a model of this type to keep a record of it for later reference along with the two-dimensional conceptual sketches. The addition of a cardboard figure will work a little magic and allow the viewer to visualize the assemblage of scraps at a human scale. Furthermore, this conceptual, putative type of model, however simple, can often be a great aid in formulating ideas. It serves the function of a three-dimensional rough sketch, and its value should not be underestimated merely because of its unimpressive appearance.

Experimental model built from ‘found’ objects.

SKETCH MODELS

The designer may produce several models before beginning work on the final version. These, however, will be ‘working’ models, quickly and easily constructed and intended to be broken apart or rebuilt in much the same way that we may erase or redraw the hasty conceptual scribbles in our sketchbooks. They are, in fact, three-dimensional rough sketches, and although often very crudely constructed, can form an invaluable tool in the design process.

Stage designers work to strict time scales, so it is not a good idea to spend a great deal of time making sketch models, whose function is merely temporary. The presentation model will inevitably take many hours to construct, so the designer needs to find a way to produce a sketch model within a matter of minutes. It is sometimes possible to sketch the main shapes on to scrap card, cut them out with a pair of scissors, and stick the pieces together with Sellotape to give a very quick impression of a set; but if you have already begun some working drawings, it does not take much time and effort to trace these off on to card, cut out the pieces and rapidly assemble them to give a reasonable impression of the finished set.

Elements copied from the working drawings, regrouped with added tabs to aid assembly, and printed on to thin card stock ready to be cut out for a speedily produced sketch model.

The sketch model for a production of Joe Orton’s What the Butler Saw photographed after a meeting with the director. Plastic furniture of an appropriate size bought from a toyshop has been used to plan furniture arrangements. The director was Ron Jenkins.

If you work digitally and are producing technical drawings by CAD, this process becomes even easier: use your CAD program to eliminate all the extraneous details in your working drawings such as borders and dimension lines, and add ‘tabs’ in appropriate places to help in gluing the pieces together; then print out the pieces on to thin card with a desktop printer, and you have a simplified version of the set all ready to cut out and assemble like a model from a child’s cut-out book. You will probably have to work at a comparatively small scale such as 1:50 (or ¼in to 1ft) to fit the pieces on to A4- (or ‘letter’-) size sheets. Many corners that will have to be carefully cut and joined with glue in the final model can just be folded in the sketch model by ‘scoring’ the lines with a blunt blade and a metal ruler before folding to produce a clean fold.

Scoring card with the back of the blade for a neat fold.

It can be very useful to have a sketch model of this type available for creative discussions with the director, because its rough, temporary nature means that one feels free to draw on it with felt-tip pens, cut pieces away with scissors or stick extra pieces on to it without destroying hours of painstaking work. A digital photograph of the model taken immediately following a creative meeting of this kind will serve as a reminder of the discussion, and can provide useful visual reference when revising drawings for the final model.

THE ‘WHITE CARD’ MODEL

Usually this is, quite simply, a presentation model at an intermediate stage of construction. Before a model is finalized with all its finished detailing, texture and paint, it can be usefully viewed as a three-dimensional diagram of the set that can show many of the technical aspects involved in its construction even more clearly than the fully finished presentation model. For this reason, the designer may sometimes present his model in this form at an early production meeting. This is an additional reason to work cleanly, avoiding unsightly finger marks and smears of glue.

A white card model can be a very attractive object in its own right, such that sometimes the designer feels reluctant to soil its pristine clarity with a paintbrush. However, it will need to be painted eventually, so when assembling the parts of an unpainted model for presentation, take great care not to glue any parts together irretrievably that you will later need to separate for painting. It is better to provide a temporary fixing with drafting tape or pins here.

A white card model for Beth Henley’s play Crimes of the Heart ready for painting. The director was Kim McCaw.

Photograph of unpainted model for Charley’s Aunt at The Theatre Royal, York, digitally coloured and completed with an old photograph of Oxford standing in temporarily for a painted backcloth.

A digital photograph of the white card model provides an excellent subject for experimenting with colour on your computer screen using software such as Photoshop, Corel Photo-Paint or Painter.

THE PRESENTATION MODEL

This is the most detailed and elaborate type of model. It is also the most interesting and attractive to look at, and certainly takes the longest time to produce. However, its purpose it not merely to delight its viewers, but to convey a large amount of detailed information. It can be seen as a threedimensional coloured working drawing for the set, and this implies that it should be constructed as accurately as possible. It should be possible to take reasonably accurate measurements from it if necessary.

The presentation model should be well constructed so that it will not easily break apart when handled, and although it is not necessary to give the same amount of attention to the back and sides as the front of the model, they should at least be treated with neatness and care. A well made and finished presentation model demands a degree of respect and shows a professional approach on the part of the designer.

The amount of detail that should be included in the presentation model is open to debate: certainly, all parts of the set that need to be built in the theatre workshops should be represented on the model, including any built detailing. Furniture is also important, especially in a room setting, for the model will not give a reasonable impression of the complete set without it. It will probably be thought necessary to include some dressings, too, especially the larger pieces, but a problem arises in deciding where to stop: a library set lined with bookcases, for instance, will not look very effective without the books filling the shelves. It will probably be desirable to show if the books are to be neatly arranged or just carelessly pushed in, and the books might need some indication of titles on their spines to make them look like real books – but the model maker might reasonably baulk at applying gold tooling and raised bindings to several hundred scale-model books. A fine artist does not necessarily improve a landscape by painting every single leaf on a tree, but uses his artistic judgment to convey his intention.

Architectural model makers often build presentation models for proposed buildings with a large degree of stylization. Sometimes they are purely diagrammatic models, with little or no attempt at reality. However, they normally work at a much smaller scale than is usual for stage models, and colours, if suggested at all, tend to be less significant and therefore much more generalized.

Some theatrical model makers, on the other hand, delight in producing extremely detailed models, which can be quite wonderful to look at in all their exquisite detail. However, the sets that these models are intended to demonstrate can easily get lost in sheer admiration for the skill of the model maker. In the end, the amount of detail to be included is a matter for individual taste and judgment, and often becomes merely a question of the amount of time available for construction.

The same comments might apply to the figures included in some models: a scale figure is an extremely valuable adjunct to any scale model, allowing the viewer to gain an immediate sense of its scale. However, a whole cast of finely modelled and painted three-dimensional figures, delightful though they may be, can sometimes create the impression of an elaborate toy and confuse the more serious purpose of the model.

Presentation model for Opera Nuova’s production of La Périchole. Directed by Kim Mattice-Wanat.

PHOTO: JOSIAH HIEMSTRA

Detail of set model for Opera Nuova’s schools tour of The Brothers Grimm. Directed by Kim Mattice-Wanat.

THE DIGITAL MODEL

Now that we all have computers in our studios, digital imagery in various forms is commonplace, and 3D modelling programs are becoming ever more sophisticated and user-friendly. Later in this book there is a chapter devoted entirely to digital techniques, but the computer model merits a mention here, for although it usually exists only in a computer’s memory banks, it can still fulfill much the same function as a conventional model in conveying detailed information about the designer’s intentions. Moreover, technological advances mean that it is now possible for a designer to produce a physical scale model from his computer, that can be handled and used in the same way as any other kind of model. The process is discussed in Chapter 10.

A digital model of the set for What the Butler Saw at the Timms Centre for the Arts, Edmonton, Canada. Directed by Ron Jenkins.

MODELS DESIGNEDFOR EXHIBITION

You may wish to exhibit your work in an exhibition such as those organized by the Society of British Theatre Designers (SBTD), or the Prague Quadrennial Exhibition organized by the Organisation Internationale de Scéongrafes, Techniciens et Architectes de Théâtre (OISTAT). In this case the organizing body will define its specific requirements, but you should bear in mind that the model will need to be transported quite a long way to the exhibition space, and might be set up by someone else in your absence. Everything in the model should be very firmly secured in position to ensure that your model will be seen exactly as intended. You will be expected to pay an exhibition fee, and probably an additional fee to include a photograph of your design in the catalogue. Don’t forget to arrange for collection or disposal of your model when the exhibition closes.

From time to time the designer/model maker is asked to produce a model specifically intended to impress potential backers or sponsors of an intended production. The management may be unable to proceed until a sufficient amount of money has been raised to cover costs, but backers (sometimes called ‘angels’ in theatre jargon) or other parties may be unwilling to invest until they are convinced that the production is already in preparation and will definitely take place. An impressive-looking model of the set design can help here, and you may be asked to produce one. However, bear in mind that this type of model does not have quite the same function as a normal set model, because in this case it is designed deliberately to impress, and will probably need a very high level of finish.

Pay some attention to the back and sides, and glue all pieces together very firmly on a strong base, because this model may be carried from place to place in the back of a car, and could come in for some rough treatment. Cover the bottom of the model with baize or felt: it may be presented to a group sitting around a highly polished boardroom table, and deep scratches on the surface of the table as it is passed around could jeopardize the whole production. The set shown in this type of model may not, in fact, be the set that will eventually end up on stage – however, do not make the mistake of showing an over-elaborate set that might look far too expensive and impractical. Potential investors will want to ensure that their money is going to be well spent, and it is better to show a good, practical set and a model that, in this particular case, includes all the fine detail you can manage.

Tactical Model-Making

It is not at all unusual for the designer’s concept to surpass the budget allocated to a production, and the white card model is a good tool for estimating costs and trying to decide where cuts can be made to bring the set within budget. However, these discussions are frequently somewhat one-sided, for it is not usually taken into account that it is often just as easy (if not easier) to adjust the budget as the set.

It is not unheard of, therefore, for a designer to resort to subterfuge when these budgetary problems are anticipated: sometimes an element such as an elaborate backing, a large rostrum area, or some type of ceiling is very lightly glued into the white card model, so that when the discussion reaches an impasse, the designer can make the handsome gesture of removing this element from the model, thereby giving the impression that he has made a considerable sacrifice in his design. This will usually encourage the management to make a reciprocal gesture, and a little more money is made available to make the remaining set viable, so all parties are satisfied.

This is, of course, basically dishonest, and the author cannot be expected to recommend it. He merely points out that it is a tactic that has been employed with remarkable success from time to time.

Part of the American pavilion at the Prague Quadrennial Exhibition of stage design in 2007.

PHOTO: PETER RUTHVEN HALL

Don’t forget, that although this type of model does not need to have all the practical aspects of the design fully worked out in detail, the higher degree of finish expected does require a lot of extra work on the part of the model maker. It should, therefore, attract a reasonable fee in addition to the normal design or model-making fee you may have been offered for the show.

From time to time the designer is asked if he would be willing to allow his set model to be exhibited in the foyer of the theatre. You may feel flattered when this happens, but ask some pertinent questions before you give your permission:

1.

Where exactly will the model be exhibited? If it is just placed on an ordinary table it will be seen mainly from above, and may not look very impressive from this angle. A set model always looks its best when viewed at eye level.

2.

Will it be possible to light the model effectively? A model does not always look impressive under normal lighting conditions, so a good light source, even if only from a carefully positioned desk lamp, can make a huge difference.

3.

Will you be properly credited for your work? There should be a well placed label showing who designed the set and built the model.

4.

Will the model be secure if left unattended? It is very difficult for anyone looking at a scale model to keep their fingers away, and after it has been poked and probed by a large number of fingers, the model will rapidly begin to deteriorate, and small loose pieces such as furniture will inevitably disappear altogether. A sign reading ‘Please do not touch’ is simply not sufficient protection.

5.

Do you really want the audience entering the theatre for a performance to be able to anticipate that first exciting view of the set as the curtain rises, or in its carefully lit and presented pre-set state? By exhibiting the set model you could be guilty of spoiling a little piece of the theatrical magic that the director and designers have attempted to create.

Early stages in construction of the set model for Street Scene. Parts for steps have been cut out and are being assembled using a plan of the unit as a guide.

3 TOOLS AND MATERIALS

SETTING UP A STUDIO