Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

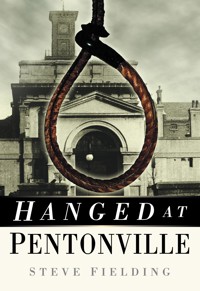

The history of execution at Pentonville began with the hanging of a Scottish hawker in 1902. Over the next sixty years the names of those who made the short walk to the gallows reads like a who's who of twentieth-century murder. They include the notorious Dr Crippen, Neville Heath, mass murderer John Christie of Rillington Place, as well as scores of forgotten criminals: German spies, Italian gangsters, teenage tearaways, cut-throat killers and many more. Infamous executioners also played a part in the gaol's history: the Billington family of Bolton, Rochdale barber John Ellis and Robert Baxter of Hertford who, for over a decade, was the sole executioner at Pentonville. For many years the prison was used to train the country's hangmen, including members of the well-known Pierrepoint family, Harry Allen and Robert Leslie Stewart, the country's last executioners. Fully illustrated with photographs, news-cuttings and engravings, Hanged at Pentonville is bound to appeal to anyone interested in the darker side of London's history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 350

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HANGED AT

PENTONVILLE

STEVE FIELDING

First published in the United Kingdom in 2008 by Sutton Publishing Limited

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Steve Fielding, 2008 2013

The right of Steve Fielding to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5339 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Research Material & Sources

Introduction

1.That Dollar I Lost

John MacDonald, 30 September 1902

2.‘May God Bless Her Dear Little Heart’

Henry Williams, 11 November 1902

3.Before 12 O’clock Tomorrow

Thomas Fairclough Barrow, 9 December 1902

4.Unwanted Advances

Charles Jeremiah Slowe, 10 November 1903

5.Murder on the High Seas

John Sullivan, 12 July 1904

6.‘No Murder Was Intended’

Joseph Potter & Charles Wade, 13 December 1904

7.‘When the Time Comes’

Albert Bridgeman, 26 April 1905

8.The Bodies in the Trunk

Arthur Devereux, 15 August 1905

9.‘No Idle Threats’

George William Butler, 7 November 1905

10.Death on Shaftesbury Avenue

John Esmond Murphy, 6 January 1909

11.The Brothers

Morris & Marks Reubens, 20 May 1909

12.A Humble Revenge

Madar Lal Dhingra, 17 August 1909

13.The Ealing Murder

George Henry Perry, 1 March 1910

14.Beyond Endurance

Hawley Harvey Crippen, 23 November 1910

15.God’s Will Be Done

Noah Woolf, 21 December 1910

16.‘Nothing But Death Shall Part Us’

Michael Collins, 24 May 1911

17.The Last Voyage

Francisco Carlos Godhino, 17 October 1911

18. The Fire-Starter

Edward Hill, 17 October 1911

19.The Gambling Den Murders

Myer Abramovitch, 6 March 1912

20.A Study in Greed

Frederick Henry Seddon, 18 April 1912

21.Murder at Fenchurch Street Station

Edward Hopwood, 29 January 1913

22.Overcome with Jealousy

Henry Longden, 8 July 1913

23.The Cellar Cemetery

Frederick Albert Robertson, 27 November 1913

24.Lost in Translation

Lee Kun, 1 January 1916

25.In This Dreadful Place

Roger David Casement, 3 August 1916

26.The Damning Letter

William James Robinson, 17 April 1917

27.‘Blodie Belgium’

Louis Marie Joseph Voisin, 2 March 1918

28.A Murderous Rampage

Henry Beckett, 10 July 1919

29.The Separation Order

Thomas Foster, 31 July 1919

30.House of Sin

Frank George Warren, 7 October 1919

31.This Affair…

Arthur Andrew Clement Goslett, 27 July 1920

32.The Black Fast Murder

Marks Goodmacher, 30 December 1920

33.The Fraudster

Frederick Alexander Keeling, 11 April 1922

34.Key Witness

Edmund Hugh Tonbridge, 18 April 1922

35.Whispers on the Stairs

Henry Julius Jacoby, 7 June 1922

36.The Newly-weds

William James Yeldham, 5 September 1922

37.Do Something Desperate

Frederick Edward Francis Bywaters, 9 January 1923

38.The Woman in the Cab

Bernard Pomroy, 5 April 1923

39.The Guilty Secret

Rowland Duck, 4 July 1923

40.‘Not Playing the Game’

George William Barton, 2 April 1925

41.Caught Red-Handed

William John Cronin, 14 August 1925

42.Prime Suspect

Arthur Henry Bishop, 14 August 1925

43.The Night-Time Dandy

Eugene de Vere, 24 March 1926

44.Joe the Painter

Johannes Josephus Cornelius Mommers, 27 July 1926

45.The Grudge

Hashan Khan Samander, 2 November 1926

46.The Carriage

James Frederick Stratton, 29 March 1927

47.In a Blue Funk

John Robinson, 12 August 1927

48.Death on a Country Road

Frederick Guy Browne, 31 May 1928

49.The ‘Drummer’

Frederick Stewart, 6 June 1928

50.Alias Mr Dennis

Frank Hollington, 20 February 1929

51.A Family Matter

William John Holmyard, 27 February 1929

52.A Head Full of Jealous Ideas

Alexander Anastassiou, 3 June 1931

53.The Killing of ‘Pigsticker’

Oliver Newman & William Shelley, 5 August 1931

54.The Ship’s Mate

William Harold Goddard, 23 February 1932

55.The Frightened Woman

Maurice Freedman, 4 May 1932

56.The Nephew

Jack Samuel Puttnam, 8 June 1933

57.Shots in the Kitchen

Varnavas Loizi Antorka, 10 August 1933

58.The Ne’er Do Well

Robert James Kirby, 11 October 1933

59.Suspicions

Harry Tuffney, 9 October 1934

60.To Get on in the World

John Frederick Stockwell, 14 November 1934

61.A Little Clandestine Business

Charles Malcolm Lake, 13 March 1935

62.Last Minute Evidence

Allan James Grierson, 30 October 1935

63.On Lovers’ Lane

Leslie George Stone, 13 August 1937

64.The Coronation Day Murder

Frederick George Murphy, 17 August 1937

65.Self First, Self Last, Self Always

John Thomas Rodgers, 18 November 1937

66.Mistaken Identity

Udham Singh, 31 July 1940

67.Operation Sea Lion (1)

Carl Meier & Jose Waldburg, 10 December 1940

68.Operation Sea Lion (2)

Charles van den Kieboom, 17 December 1940

69.The Fire of the Underworld

Antonio Mancini, 31 October 1941

70.Beneath the Flagstones

Lionel Rupert Nathan Watson, 12 November 1941

71.‘Old Moules’

Samuel Dashwood & George Silverosa, 10 September 1942

72.The Deserter

William Henry Turner, 24 March 1943

73.The Supreme Fatalist

Gerald Elphinstone Roe, 3 August 1943

74.The Old Flame

Charles William Koopman, 15 December 1943

75.For Thirty Shillings

Christos Georghiou, 2 February 1944

76.The Hollow Keys

Oswald John Job, 16 March 1944

77.Pour Decourager Les Autres

Pierre Richard Charles Neukermans, 23 June 1944

78.The Reluctant Spy

Joseph Jan Van Hove, 12 July 1944

79.In Search of Excitement

Karl Gustav Hulten, 8 March 1945

80.The Comrie Camp Murder

Erich Koenig, Joachim Palme Goltz, Kurt Zeuhlsdorf, Heinz Brueling & Josef Mertins, 6 October 1945

81.The Innocent Victim

Armin Kuehne & Emil Schmittendorf, 16 November 1945

82.Shots in the Dark

James McNicol, 21 December 1945

83.Pressing Debts

John Riley Young, 21 December 1945

84.The Last Traitor

Theodore John William Schurch, 4 January 1946

85.The Charmer

Neville George Clevely Heath, 16 October 1946

86.The Tell-Tale Cartridge

Arthur Robert Boyce, 1 November 1946

87.For Clothing Coupons

John Fleming McCready Mathieson, 10 December 1946

88.The Secret Affair

Frederick William Reynolds, 26 March 1947

89.Shot Down in the Street

Christopher James Geraghty & Charles Henry Jenkins, 19 September 1947

90.The Watchmaker

Walter John Cross, 19 February 1948

91.The Cartoonist

Harry Lewis, 21 April 1949

92.A Sordid Tale

Bernard Alfred Peter Cooper, 21 June 1949

93.Desperate Measures

William Claude Hodson Jones, 28 September 1949

94.The Son-in-Law

Daniel Raven, 6 January 1950

95.Hanged and Innocent?

Timothy John Evans, 9 March 1950

96.The Urge to Destroy

John O’Connor, 24 October 1951

97.The Drug Dealer

Backary Manneh, 27 May 1952

98.Those Fatal Seconds

John Howard Godar, 5 September 1952

99.The Fantasist

Dennis George Muldowney, 30 September 1952

100.‘I Just Don’t Want to See You Anymore’

Raymond John Cull, 30 September 1952

101.When Friends Fall Out

Peter Cyril Johnson, 9 October 1952

102.The House of Death

John Reginald Halliday Christie, 15 July 1953

103.Like a Madman

George James Newland, 23 December 1953

104.Partners in Crime

Ian Arthur Grant & Kenneth Gilbert, 17 June 1954

105.The Accomplice

Joseph Chrimes, 28 April 1959

106.Manhunt

Ronald Henry Marwood, 8 May 1959

107.Common Design

Norman James Harris, 10 November 1960

108.Portrait of a Killer

Edwin Albert Arthur Bush, 6 July 1961

Appendix: List of persons hanged at Pentonville 1902–1961

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Iwould like to thank the following people for help with this book. Firstly to Lisa Moore for her help in every stage in the production, but mainly with the photographs and proofreading. I offer my sincere thanks to both Matthew Spicer and Tim Leech, who have been willing to share information along with rare documents, photographs and illustrations from their own collections. I would also like to acknowledge the help given by Janet Buckingham who helped to input the original data and to Gillian Papaioannou who proofread and edited the final drafts.

RESEARCH MATERIAL & SOURCES

As with my other books on capital punishment and executions, many people have supplied information and photographs over the years, some of whom have since passed away. I remain indebted to the help with rare photographs and material given to me by the late Syd Dernley, (assistant executioner), and former prison officer, the late Frank McKue.

The bulk of the research for this book was done many years ago, and extra information has been added to my database as and when it has become available. In most instances, contemporary local and national newspapers have supplied the basic information, which has been supplemented by material found in PCOM, HO and ASSI files held at the National Record Office at Kew. I have been fortunate to have access to the Home Office Capital Case File 1901–1948, along with personal information in the author’s collection from those directly involved in some of the cases.

Space doesn’t permit a full bibliography of books and websites accessed while researching this project. I have tried to locate the copyright owners of all images used in this book, but a number of them were untraceable. In particular, I have been unable to locate the copyright holders of a number of images, mainly those sourced from the National Archives. I apologise if I have inadvertently infringed upon any existing copyright.

The author, Steve Fielding.

Steve Fielding, 2008www.stevefielding.com

INTRODUCTION

HM Prison Pentonville is one of the most famous prisons in the country. Situated in north London, it has housed a host of famous prisoners including Oscar Wilde and spy Dr Klaus Fuchs. It was opened in 1842 to replace the Millbank Penitentiary, the first modern prison, which, although only 25 years old, had proved unsatisfactory and outdated. Designed by Lt-Col Jebb, RE, it had taken two years to build the new Pentonville Prison, and cost over £84,000.

Standing in 8 acres, surrounded by an 18ft perimeter wall, its radial wing design was influenced by the ‘separate system’ developed at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia. This meant that a single prison officer standing in the centre could, by turning his head, view all four wings in turn.

The new prison had separate cells for 520 prisoners, and its design proved so satisfactory to the government that a programme of prison building began. This was two fold; the increase in population brought with it an increase in the crime rate, and with the use of transportation to the colonies for convicted criminals coming to an end, new prisons were now needed.

The cells at Pentonville, which under the separate system meant each convict had his own cell which measured 13ft long, 7ft wide and 10ft high, with a small window 4½ins square, high on the wall, which could be opened for ventilation. Conditions in the new prison were a vast improvement on the archaic Newgate Gaol and other older establishments. Prisoners were encouraged to undertake work, such as coir picking (un-threading old tarred rope) and basket weaving.

In the twentieth century, the cells were updated and modernised, with the installation of electric light and improved sanitation. In 1941, the gaol suffered a direct hit from an enemy bomb on C Hall and as a result, the hall was split into two. The gable ends were bricked up, and the isolated building, sometimes known as the ‘stump’, or H Hall, was partially separated from the rest of the prison and linked only by a corridor.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the execution chamber was situated in the prison grounds at the end of B Hall, which also housed the original condemned cells. This necessitated the condemned men having to walk from the cell to the gallows, which often proved to be an ordeal for a terrified prisoner. In 1928, in line with the modernisation of many other prisons, a new execution suite was built at Pentonville. It was now located in A Hall, close to the prison entrance, and consisted of a gallows room situated between two condemned cells built into the prison wing. The execution suite was constructed over three floors. The ground floor cell ceiling housed the trapdoors through which the prisoner dropped. The middle floor was the gallows room into which the condemned would walk directly from the condemned cell, a distance of just a few feet. Painted pale green, it contained the lever and trapdoors of two heavy oak leaves, each measuring 8ft 6ins long by 2ft 6ins wide. The cell above housed the beams and chain mechanisms to which the noose was attached.

Plan of Pentonville Prison in the 1950s. (Author’s collection)

Pentonville Prison at the turn of the twentieth century. (Author’s collection)

The Old Bailey in the early part of the twentieth century. Most men hanged at Pentonville had been sentenced to death here. (Author’s collection)

It wasn’t until the closure of Newgate in 1902 that prisoners under sentence of death were housed at Pentonville, and following the closure of the former, the gallows, supports and beams, along with the trapdoors and mechanisms were transported across the city and installed.

Following an upheaval in the whole procedure of recruiting and training executioners in the late 1890s, anyone wishing to become an executioner would have to attend a course of instruction before being placed on the official list. The first courses took place at Newgate in 1900, but following its closure, the executioners’ training school was transferred to Pentonville. Among the first hangmen to graduate were Tom Pierrepoint and William Willis, who both went on to have long careers on the gallows. All would-be hangmen graduated at Pentonville until 1960 when training was transferred to Wandsworth Prison, South London.

People who applied to be added to the Home Office list of executioners had to first of all face an interview at a prison close to their home. This was designed to weed out unsuitable applicants whose motives to apply may have been fuelled by a gruesome or perverted interest. Those who were successful were invited to attend the one-week course at Pentonville, with expenses and travel paid for by the Home Office, where they were taught how to pinion the prisoner, calculate and rig the drop, and to carry out a mock execution using a dummy. The applicants were constantly monitored, and speed, efficiency, nerve and discretion were all requisites of a hangman.

LP.C4 sheet used by prison officials for recording information on executions. (Author’s collection)

Equipment needed to rig the gallows, including the ropes and straps, along with the block and chains used for removing the prisoner from the gallows, were housed in special execution boxes and stored at Pentonville. They would be despatched by rail to prisons around the country where needed.

Apart from its fellow London prison at Wandsworth, Pentonville was the busiest prison in the country for executions, with 120 people ending their lives on the gallows there. There are a number of reasons for the higher than normal count: several spies and German PoWs convicted by court-martial were hanged at Pentonville, and the prison also received prisoners sentenced to death from further afield than north London, when many provincial prisons were down-graded around the time of the First World War. Therefore, prisoners, who may once have been hanged at rural prisons such as Chelmsford and Hertford, were now transferred to Pentonville for execution.

The first hangmen to officiate at Pentonville were William and John Billington, the last members of that family, whose dynasty stretched back to the 1880s. Both members were assisted by Henry Pierrepoint, the first of a new family of executioners, and a name that stayed at the head of the short official list of hangmen until the late 1950s.

Rochdale barber John Ellis’ first engagement as chief executioner at Pentonville was to hang Dr Crippen, and in the next thirteen years, he made over twenty visits to the prison in the capacity of executioner. In 1925, Hertford hangman Robert Orridge Baxter took over the mantle of chief executioner at the prison, and for the next decade carried out every execution at the gaol, until his failing eyesight meant that he was no longer fit for duty.

Hangman’s Table of Drops: devised at the end of the nineteenth century to help the hangman work out the correct drop. This version dates from 1913. (Author’s collection)

William Billington, the first hangman to officiate at Pentonville. (Author’s collection)

‘Crippen’s Grass’ at the end of B Hall. (Author’s collection)

Tom Pierrepoint, William Willis and Alfred Allen also pulled the lever at executions there, and it was at a Pentonville execution that Willis’ conduct was brought into question and led to his dismissal (see Chapter 44). Another hangman whose career ended at Pentonville was Stanley Cross of Fulham. Cross had graduated from Pentonville in the autumn of 1932 and was promoted to chief executioner at the start of the Second World War. He executed Udham Singh in July 1940 and three spies that December, and on each occasion Dr James Liddell, Chief Medical Officer at the gaol, noted on the official post execution forms that he didn’t think Cross was competent in calculating the drops needed to dispense instant death, despite his having access to a Table of Drops.

Albert Pierrepoint made his debut as chief executioner at Pentonville on 31 October 1941, and vied with his uncle, Tom, for work at the prison during the war. From 1946, with his uncle now pensioned off, Albert carried out every execution until the temporary suspension of capital punishment in 1956, when the death penalty was being debated in parliament and which led to the passing of the Homicide Act in 1957. This new Act categorised types of murder and led to a drastic reduction in executions being carried out.

By the time hangings were re-introduced, Pierrepoint had tendered his resignation, and the chief executioner was now Harry Allen, a publican living in the Manchester area. Allen officiated at three of the four post-Homicide Act executions at Pentonville, with Robert Leslie ‘Jock’ Stewart carrying out the other, that of Norman Harris. Both Stewart and Allen had assisted Albert Pierrepoint at the gaol on many occasions.

Like many Victorian prisons, Pentonville is believed to be haunted. One of the ghostly apparitions said to walk the grounds at the prison is Dr Crippen, hanged in November 1910 for the murder of his wife. A piece of grass adjacent to the original execution shed, is known to this day as ‘Crippen’s Grass’, and it is here that it is claimed that his ghost, complete with a crooked neck, can be seen to wander.

HMP Pentonville remains in use as a major London prison to this day, holding around 1,100 prisoners remanded both by Magistrates and Crown Court, along with those serving short sentences or beginning longer sentences.

This book looks in detail at the stories behind why 120 murderers, spies and traitors were all Hanged at Pentonville.

1

THAT DOLLAR I LOST

John MacDonald, 30 September 1902

On a hot July evening in 1902, a small sum of money was stolen from John MacDonald, a 24-year-old costermonger, as he slept in a run down Salvation Army shelter on Middlesex Street in London’s Aldgate district. Discovering the theft, he looked at the other lodgers, and instantly suspected 30-year-old Irish ex-soldier Henry Groves. Confronted with the accusation, Groves, known as ‘Mickey the Irishman’ denied the theft, but MacDonald was not satisfied and Groves’ disappearance from the lodging house on the following day seemed to confirm his suspicions.

Scotsman MacDonald was not going to let the matter drop, and a few days later he was seen at the shelter sharpening his knife, muttering that he was going to ‘kill Groves over that dollar I lost.’

On Thursday, 28 August, seeing Groves enter a shop in Old Castle Street, MacDonald followed him inside, and when a row broke out between the two, they were asked to leave. Groves left first and began walking towards Wentworth Street. MacDonald followed a few moments behind, and as they approached a school at the top end of the street, where Groves worked as the caretaker, MacDonald approached, grabbed him by the shoulder and began to punch him. Groves hit back, knocking MacDonald to the ground. As the fight escalated, Sam Dodds, a friend of Groves, tried several times to pull them apart, as another man ran to find a policeman. Groves gave as good as he got, but as his strength began to sap, he attempted to make his escape. As Groves turned on his heels, Dodds saw MacDonald draw a knife from his pocket, and although he tried one last time to help, he watched helplessly as MacDonald caught Groves by the arm, twisted him around and plunge the knife into his neck, severing an artery and cutting his windpipe. Groves staggered along the street, with blood oozing from the terrible wound, as Dodds managed to wrestle MacDonald to the ground and detain him until the police arrived. Groves collapsed and died from his injuries before medical assistance could be given.

At his Old Bailey trial before Mr Justice Walton on Thursday, 11 September, MacDonald’s defence was that he was so drunk when the murder took place, he had no recollection of committing any crime. Evidence of his threats to kill Groves over the money he had stolen was given in court, as was evidence of a friend of MacDonald’s who testified that less than an hour before the murder, he had made a similar threat. Evidence was also heard of a statement MacDonald made at Spitalfield’s police station. When pointing to the knife he claimed; ‘That’s the knife I did it with… I did it intentionally.’

Hanged just thirty-three days after committing the brutal murder, John MacDonald holds the dubious honour of being the first man to be executed at Pentonville, the gallows’ beams and posts having been recently installed, following removal from the recently closed and soon to be demolished Newgate Gaol.

2

‘MAY GOD BLESS HER DEAR LITTLE HEART’

Henry Williams, 11 November 1902

Having fought bravely on the front line in the Boer War, 31-year-old Henry Williams left the 4th East Surrey Militia and returned to his lodgings at Fulham in July 1902, expecting to resume his relationship with widow Ellen Andrews, the mother of his beloved 5-year-old daughter, Margaret ‘Maggie’ Anne Andrews. Although they had not married, Williams and Ellen had been together for almost a decade, and they had kept in regular contact by letter while he was in South Africa.

Returning home that summer, Williams began to suspect that Ellen had been unfaithful to him, and had been carrying on an affair with a sailor while he was away fighting for his country. Although she admitted knowing the sailor, Ellen denied that anything untoward had taken place, but Williams was not convinced.

In early September, Ellen took Maggie to stay in Worthing, Sussex, and on 10 September, Williams travelled down to see them, in order to collect Maggie and take her back to London with him. Still convinced Ellen had been unfaithful, the visit ended in a fierce quarrel, and as he was leaving to return to London, Williams made a chilling parting statement: ‘I will not hurt you Ellen’ he said coldly, ‘but I will do something which will break your heart and brand you so that you will never hold your head up in this world again.’ Quite what she imagined he would do is not known, but it probably never crossed her mind the lengths to which her suspected infidelity had driven him.

Later that evening and back in London, Williams was having a drink in the Lord Palmerston public house on the Kings Road, Fulham. Williams was sitting with friends when he began to speak about his feelings for his daughter. He pulled out a photograph and tears welled up in his eyes as he spoke: ‘Do you think I can let my little Maggie call another man daddy? It would drive me stark raving mad.’ He then began to ramble, but the gist of it seemed to suggest that he had killed his daughter. One of his friends became so concerned at what he was hearing that he went in search of a policeman. When he returned in the company of Detective Inspector Walter Dew (later to find fame as the man who caught Dr Crippen), Williams finished his drink and climbed to his feet. ‘I know what you have come for – for killing my little girl. God bless her. I will swing for it like a man.’

Henry Williams as sketched in court. (T.J. Leech Archive)

Hangman Henry Pierrepoint assisted William Billington at the execution of Henry Williams. He later described Williams as the bravest man he ever hanged. (Author’s collection)

With Williams held in the local police station, officers went to his lodgings and discovered the body of his beloved daughter lying on a bed, covered over with the Union Jack flag. Beside the body was a note which read, ‘May God bless her dear little heart, and may her good soul go to heaven, and may I, her heartbroken father, be forgiven.’

Tried at the Old Bailey before Mr Justice Jelf on 23 October, Williams’ defence was based on insanity through jealousy at the time of the murder. Ellen Andrews, whose infidelity Williams strongly suspected but had never confirmed, was the subject of verbal abuse from a large section of the crowd when she made her way into court. She sat in tears in the dock as the court heard Williams say he had killed Maggie ‘so that she wouldn’t grow up to be like her mother’.

Williams said that after putting his daughter to bed, he told her they were going to play a game. He covered her eyes with a handkerchief and then cut her throat, placing a doll next to her body.

The jury returned a guilty verdict with a recommendation for mercy, and when asked if he had anything to say before sentence was passed, Williams stood erect and in a firm voice said, ‘Nothing whatsoever; I am only too pleased to receive it and get out.’

Williams kept his composure throughout his time in the condemned cell, chatting and playing cards with the warders. On the night before his execution he said he had killed his daughter because he feared that if she was brought up by her mother, she would grow up to be unfaithful and would break men’s hearts.

Henry Pierrepoint, who assisted hangman William Billington, later recorded that Williams was the gamest and bravest man he had ever executed and that he had shown no fear as he was led to the gallows.

3

BEFORE 12 O’CLOCK TOMORROW

Thomas Fairclough Barrow, 9 December 1902

It was a most unusual relationship. Thirty-two-year-old Emily Coates was the illegitimate stepdaughter of Thomas Fairclough Barrow, a 49-year-old dock labourer. When Barrow was widowed fifteen years before, Emily stayed with her stepfather and the relationship soon developed into a semi-incestuous one, and during that time she bore him several children, although only one, a boy, survived.

By the autumn of 1902, they were living together to all intents and purposes as man and wife in a two-room apartment on Red Lion Street, in a run down part of Wapping. Strange as the relationship was, it was also an unhappy one. Emily frequently complained to friends that Tommy beat her, and following one particularly fierce assault, she fled and took refuge in a friend’s house at nearby Shadwell.

On Friday night, 10 October, Emily turned up in tears on the doorstep of her friend and neighbour, Jane Corker’s house, complaining of being beaten and kicked by Barrow, and asked if she could stay the night. Her neighbour agreed. Six days later, Emily served Barrow with a writ for assault which needed to be responded to within forty-eight hours. On the following night, warrant in hand, Barrow went to where Emily was staying and demanded to see her. Told she was out, he began issuing a number of threats that he would resolve his grievances with her imminently. Shouting through the letterbox, Barrow proclaimed coldly that they weren’t idle threats as, ‘you shall know before 12 o’clock tomorrow.’

On the following morning, as Emily walked to work down nearby Glamis Road, Barrow ran up behind her and stabbed her five times – once in the heart – killing her instantly. Barrow was arrested within minutes and seemed resigned to his fate. ‘This will end it all. Now all I want is a rope around my neck.’

During his trial at the Old Bailey on 19 November, Dr James Scott, medical officer at Brixton Prison, who had examined Barrow while he was on remand, told the court that the prisoner had complained of headaches and claimed to have suffered from sunstroke while serving in the Navy.

His counsel pleaded vainly that when Barrow had killed Emily, he was temporarily not responsible for his actions and was therefore not guilty of wilful murder. The jury rejected those claims; not even leaving the dock before indicating to Mr Justice Bigham that they believed Barrow was indeed guilty as charged.

4

UNWANTED ADVANCES

Charles Jeremiah Slowe, 10 November 1903

To 20-year-old barmaid Martha Jane Hardwick, he was becoming a pest. She was used to the flirting and suggestive chat from the regulars at the Lord Nelson public house at Whitechapel, but whereas most customers knew where to draw the line, 28-year-old Charlie Slowe was beginning to make her feel uncomfortable.

Martha lived at the pub, which was owned and run by her sister, Jane Starkey, and throughout the summer of 1903, she had grown to dread the pint sized, stockily built, dock labourer entering the bar. Without fail, Slowe would make a point of asking Martha to go out with him, usually when he was drunk. When it became clear that he was taking no heed of her refusals, she took to avoiding him when he came to the pub, and would busy herself with other customers or find some other chore to take her away from the bar if business was quiet.

Slowe gradually began to feel that she was making a fool of him by discussing his failed advances with other barmaids, and early in September a lodger at the Lord Nelson heard Slowe threaten to stab Martha if she continued to shun him.

In the early evening of Wednesday, 23 September, Slowe visited the pub, and seeing him enter the bar, Martha immediately went to serve in another room. When she went back into the main bar a short time later, she saw that he had gone and breathed a sigh of relief as she carried on serving. There were no licensing laws of note in the early part of the twentieth century and unfortunately for Martha, Slowe returned to the Lord Nelson shortly after midnight. Seeing her standing close to the bar, Slowe approached and struck out, hitting her on both shoulders. Although witnesses thought he had used his fists, he had in fact been holding a sharp knife.

‘I’ve got you now,’ he shouted as Martha slumped to the floor, fatally wounded. Slowe fled from the bar, with landlady Jane Starkey in pursuit, shouting for help and asking people to stop him. A burly docker detained Slowe who was brought back to the public house. In his pocket was a bloodstained knife.

Tried before Mr Justice Bigham at the Old Bailey on 21 October, Slowe’s defence stated that a mixture of provocation and drink had led him to commit murder. The prosecution refuted this by saying the police surgeon who had examined him shortly after his arrest confirmed that he was only mildly drunk, certainly not enough to have been unaware of his actions. They also dismissed the issue of provocation, saying that rather than being provoked, he had simply killed Martha because she had rejected his unwanted advances.

5

MURDER ON THE HIGH SEAS

John Sullivan, 12 July 1904

‘I consider that the judge summed up the case as if he had a personal spite against me, and he also went to sleep while my lawyer was pleading for my life.’ (Statement by John Sullivan, following the passing of the sentence of death.)

After two months on the high seas, the relationship between 40-year-old seaman, John Sullivan and 17-year-old cabin boy, Derek Lowthian had started to turn sour. Both had joined the SS Waiwera at London prior to it departing on 6 January 1904, bound for New Zealand, via South Africa and Uruguay.

Sullivan, a native of County Durham, soon formed an attachment to the young boy, which quickly developed into an intimate relationship. The older man had a very jealous nature and would often berate Lowthian if he saw him chatting to other deckhands, and by the time the ship reached the Cape of Good Hope, Lowthian had made it clear to Sullivan that he did not want the relationship to continue.

Sullivan, however, was smitten and had no intention of letting things go. They had a fierce quarrel that resulted in a coming to blows, and only ended when Sullivan pulled out a knife on Lowthian and threatened to ‘cut his head off!’ He was put in irons, brought before the Captain, fined and imprisoned for seven days.

When Sullivan had served his sentence and was freed to resume his duties, the two men would quarrel whenever they saw each other. On one occasion Sullivan was seen by one of his shipmates holding an axe and claiming, ‘This would be a good thing to use to do away with someone.’

On the evening of 18 May, as the ship steamed towards Tenerife, Sullivan warned Lowthian to ‘beware’ and when asked what he meant by that, he replied, ‘wait and see’, adding, ‘I will break your neck. I can’t stand this much longer and there will be a murder done before morning!’

Later that night, as Lowthian was talking to the quartermaster on deck, Sullivan appeared, carrying an axe. Before Lowthian could speak, Sullivan rained down blows on his head. The quartermaster hurried to fetch a doctor, but as medical assistance was vainly given to the stricken boy, Sullivan stood by and shouted, ‘You don’t need no doctor. He’s dead enough, I’ve knocked his brains out!’

Lowthian died within minutes and Sullivan was again put in irons. He asked to see the Captain and said there was a letter in his pocket, which would explain everything. The letter ended with the sentence, ‘I shall cut off his head and take it overboard with me’. On Thursday, 2 June, as the ship docked in the Thames, Inspector Reed boarded the vessel and arrested Sullivan. ‘I am sorry I did it, I am sorry for his parents,’ he said as he was led away.

Sullivan stood trial at the Old Bailey before Mr Justice Grantham on Thursday, 23 June. His defence claimed insanity, stating that since joining the Navy, Sullivan had suffered from heart disease, melancholia and bad teeth! The jury debated whether there were grounds for reducing the charge to manslaughter through provocation; they quickly returned a verdict of guilty as charged, but requested mercy on the grounds of provocation.

6

‘NO MURDER WAS INTENDED’

Joseph Potter & Charles Wade, 13 December 1904

The hangmen were asleep in their quarters, and in the gallows chamber two ropes hung taut, stretched with sandbags that would allow the executioners on the morrow to fix a drop accurate to the half inch. Inside two condemned cells at Pentonville, prisoners 12298 and 12299 were spending their last nights on earth oblivious to an extraordinary turn of events taking place outside.

At a few minutes to midnight on 12 December 1904, a man had walked into Whitechapel police station and asked to speak to a detective. He then made a full confession to a murder that had assistant commissioner Sir Melvin MacNaughten roused from his bed and hurrying to the station to deal with the situation. Detectives who had been investigating the brutal murder were all present, as discussions took place whether to advise the Home Secretary to cancel the executions pending further enquiries.

The confessor was grilled on several points, and after an intensive interrogation, the officers came to the conclusion his story was false. Gradually his confession was unravelled as a pack of lies, and as he was removed down to the cells, he was asked why he had volunteered a false confession. ‘I just wanted to do them a good turn’ he said, admitting that he knew neither of the two condemned men whose last hours were quickly ticking by.

It was early in the morning of Wednesday, 12 October 1904, when a paper-boy arriving for work at a newsagent and tobacconist’s shop at 478 Commercial Road, Stepney, started a major murder enquiry. Surprised to find the shop unlocked and with no sign of the proprietor, the fearsome Miss Matilda Farmer, he waited around, unsure of what to do. A short time later, another boy turned up at the shop and when told of Miss Farmer’s absence, he reported this to his employer.

The police were called, and when an officer entered the shop he found a set of false teeth and a boot lying near the counter, and a pair of glasses on the stairs. Miss Farmer was discovered lying face down on her bed, hands tied behind her back and a towel forced into her mouth. Although there was a faint pulse when the policeman checked, by the time the doctor arrived, she was dead.

The bedroom had been ransacked, and there was no sign of any money or jewellery. Evidently the killer, or killers, had found what they had come for, and with the back door locked and the windows barred, had presumably left via the front door.

A witness told detectives he had seen two men, one of whom he recognised as Charles Wade, loitering by the newsagents the night before, and then again early in the morning of the murder, shortly after Miss Farmer had opened the shop when the newspapers had been delivered. Kept under surveillance for several days, as police followed different lines of enquiry, 22-year-old Charles Wade and his 35-year-old half brother Joseph Potter (also known as Conrad Donovan), were eventually arrested, and when picked out in an identity parade at Brixton Prison, charged with wilful murder. Both had long criminal records for robbery and violence.

Appearing before Mr Justice Grantham at the Old Bailey in November, both vociferously proclaimed their innocence. None of the stolen jewels were found in either man’s house, and one of the police witnesses admitted that he had seen pictures of Wade and Potter prior to the identity parade, during which two other witnesses had failed to recognise them. Despite this, the jury took less than ten minutes to find both guilty of wilful murder.

Eight days before the men were to be hanged, workmen at the shop lifted a floorboard and discovered the hoard of cash and missing jewellery. The killers’ haul had been nothing like the police had surmised.

Although there had been some public disquiet regarding the outcome of the trial, moments before Potter was led to the gallows he turned to the prison chaplain and made a brief statement that showed that the verdict was indeed the correct one: ‘No murder was intended.’

7

‘WHEN THE TIME COMES’

Albert Bridgeman, 26 April 1905

An ear piercing scream rang out. It was in the early hours of Sunday, 5 March 1905, when Alice Shadbolt opened her door at her lodgings on Compton Street, St Pancras, and saw a man fleeing down the stairs. She ran out of her room and followed him onto the street, but he soon vanished in the warren of side streets. Returning to her home she entered the room of fellow tenant, 44-year-old Catherine Ballard, and found her lying on the floor. She had been battered on the head with a poker found beside the body, but death was due to a hideous throat wound. Her hysterical daughter told police that the killer was her former boyfriend, 22-year-old Albert Bridgeman, and a few hours later he was picked up on nearby Hunter Street. In his pocket was a bloodstained razor.

One month later at the Old Bailey, before Mr Justice Jelf, the background into the brutal murder was told before a packed courtroom. Shortly before Christmas 1904, former soldier Bridgeman and his girlfriend Catherine Ballard had called off their engagement. Although not to his choosing, the break-up was amiable enough, and they had remained on good terms. The same could not be said for relations between Bridgeman and the girl’s mother, also called Catherine Ballard.

Blaming her for the break-up, Bridgeman had re-enlisted in the army before Christmas, but keen to try to repair the broken relationship, on Wednesday, 28 February 1905, he bought his discharge. He went round to see Catherine and discovered that while he had been away, her mother had been spreading gossip about him.