14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The first edition of this book established itself as required reading for all those interested in the development of the fashion business. There are other books on contemporary dress, but this account gives particular weight to the commercial organization of the industry; from designer and textile manufacturer right through to the consumer. This completely revised edition brings the story up to the 1990s with new text, 280 illustrations and 16 color plates. Fashion in this century has ceased to be the private domain of the wealthy. The era when such names as Worth, Paquin and Sciaparelli could dominate has given way to one where style and 'look' can be taken from a host of various sources: designers and manufacturers, department and chain stores, the boutiques or the streets. This established reference work looks behind the scenes for an understanding of the social, economic and technical changes that have caused this revolution. It is a story of fashion shocks: two world wars, the impact of new fibers and manufacturing techniques, and the succession of youth explosions: mini-skirts, punk and sportswear. The narrative is based on research into the history of couture houses, retailers and manufacturers and the authors' experience and contact with the fashion business.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 533

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

HISTORY OF 20TH CENTURY FASHION

Fashion in this century has ceased to be the private domain of the wealthy. The era when such names as Worth, Paquin and Schiaparelli could dominate has given way to one where style and ‘look’ can be taken from a host of various sources: designers and manufacturers, department and chain stores, popular culture or the streets.

This new edition of a standard reference work looks behind the scenes for an understanding of the social, economic and technical changes that have caused this revolution. It is a story of fashion shocks: two world wars, the impact of new fibres and manufacturing techniques, and the succession of youth explosions: mini skirts, punk, sportswear and environmentally-conscious fashion. The narrative is based on research into the history of couture houses, retailers and manufacturers and the author’s experience and contact with the fashion business.

The first edition of this hook established itself as required reading for all those interested in the development of the fashion business. There are other books on contemporary dress, but this account gives particular weight to the commercial organisation of the industry; from designer and textile manufacturer right through to the consumer. This completely revised edition brings the story up to the 1990s with new text, illustrations and colour plates.

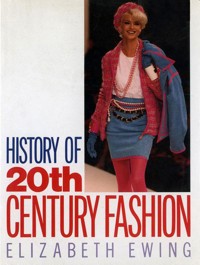

Jacket illustrations: Front: Chanel Suit 1991. courtesy of Rex Features. London: Bock: from the Paquin and Worth collections of drawings at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

A BATSFORD BOOK

Elizabeth Ewing, who died in 1986, wrote widely on fashion as well as theatre and drama. Her books included Everyday Dress, Dress and Undress and History of Children’s Costume.

Alice Mackrell who has updated the text, and written the new chapter for this edition is a fashion historian specialising in the history of fashion plates . She is the author of Shawls, Stoles and Scarves, Paul Pairet and Coco Chanel, all published by Batsford.

History of

TWENTIETH CENTURY FASHION

Elizabeth Ewing

Revised and updated by

Alice Mackrell

Acknowledgments to the Third Edition

I was delighted to be asked to update the late Elizabeth Ewing’s History of 20th Century Fashion. It is a classic book which has achieved authority in its subject. My work has been concerned with developments in fashion from 1985 to the beginning of the 1990s. I would like to thank the following people who have helped me: Philippa Baker, Caroline Neville Associates; Louise Brassey, Ralph Lauren; Moira Braybrooke, Laura Ashley; Penelope Byrde, Museum of Costume, Bath; Gill Curry, Zandra Rhodes (UK) Ltd; Ali Edney, Liberty of London Prints Ltd; Andrea Hawkins, Katharine Hamnett Ltd; Mary Hillman, Extravert by Ritva Kariniemi; G. T. Hoo and Sophie Reiner, Jasper Conran Ltd; E. James, Hackett; Joan Jones, Jaeger; Lieke Krijnen, Comme des Garçons; Karen Levi, Mulberry; Ruth Lynam, Jean Muir Ltd; Jane MacDonald, The Chelsea Design Co. Ltd; Rachel Maller, Caroline Charles; Next Press Office; Mary Phillips, Aquascutum; Julia Ruffell, Ben de Lisi; Pauline Snelson and Kate Bell, B. T. Batsford Ltd; Sara Studd, Victor Edelstein Ltd; Elaine Sullivan, Betty Jackson Ltd; Heather Tilbury and Susan Ash, Heather Tilbury Associates; Gillian Wheatcroft, Marks & Spencer; Peter Willasey, Harrods Ltd.

1992

Dr Alice Mackrell

Acknowledgments to the Second Edition

In preparing this history I have been generously helped by many people who have been actively concerned with fashion during the period of great change and expansion with which it deals. To all of them I am deeply grateful. In addition I have been greatly indebted to the staffs of the London Library, the Victoria and Albert Museum Library, the London College of Fashion and Clothing Technology Library, and the Museum of Costume, Bath.

For this, the Second Edition, further invaluable help has been given by many of today’s representatives of various areas of fashion, especially by Penelope Byrde, Keeper of Costume at the Museum of Costume, Bath, with regard to illustrations; Piers Milligan, on punk fashion; and finally by Timothy Auger and Richard Reynolds, my editors. To all these my sincere thanks.

November 1985

Elizabeth Ewing

Contents

Colour plates

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

1 Edwardian sunshine for the few, but change in the air, 1900–1909

2 Fashion spreads from the top, and many join in, 1900–1910

3 Manufacture grows, but sweated labour casts a shadow, 1900–1908

4 The start of modern fashion and the effect of World War I, 1907–1918

5 New fashion makers and the new kinds of fashion, 1920–1930

6 Developments in fashion manufacture between the wars, 1918–1939

7 Fashion by decree during and after World War II, 1939–1947

8 New looks for all from 1947

9 The young explosion splits fashion from the late 1950’s

10 Growth and prosperity of the top manufacturers, 1960’s and early 1970’s

11 Changes from the 1970’s: revolt, unexpected influences and Punk

12 Ready-to-wear: 1970’s to early 1990’s

13 Changes in the shops: 1970’s to early 1990’s

14 Fashion from the mid-1980’s to early 1990’s

Index

Bibliography

Adburgham, Alison, A Punch History of Modes and Manners, Hutchinson, 1961

Adburgham, Alison, Shops and Shopping, 1810–1914, George Allen & Unwin

Amies, Hardy, Just So Far, Collins, 1954

Ballard, Bettina, In My Fashion, Secker & Warburg, 1960

Balmain, Pierre, My Years and Seasons, Cassell, 1964

Beaton, Cecil, The Glass of Fashion, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1954

Bernard, B., Fashion in the Sixties, Academy Editions, 1978

Bell, Quentin, Bloomsbury, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968

Bell Quentin, On Human Finery, Hogarth Press, revised ed. 1976

Bradfield, Nancy, Historical Costume of England, 1066–1968, Harrap, 1970

Byrde, Penelope, A Visual History ofCostumes: The Twentieth Century, Batsford, 1986

Carnegy, Vicky, Fashions of a Decade: The 1980’s, Batsford, 1990

Carter, E., Twentieth Century Fashion. A scrapbook 1900 to Today, Eyre Methuen, 1975

Carter, E., The Changing World of Fashion, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1977

Carter E., Magic Names of Fashion, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1980

Cohn, N., Today there are no Gentlemen, Weidenfeld, 1971

Cooper, Diana, The Rainbow Comes and Goes, Rupert Hart-Davis, 1958

Creed, Charles, Maid to Measure, Jarrolds, 1961

Cunnington, C. W., Englishwomen’s Clothing in the Present Century, Faber & Faber, 1951

Davis, Dorothy, The Second IndustrialRevolution, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966

Dior by Dior, Trans. A. Fraser, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1957; Penguin Books, 1958

Disher, M. L., American Factory Production of Women’s Clothing, Devereux Publications, 1947

Dobbs, S. P., The Clothing Workers of Great Britain, Routledge, 1928

Dorner, J., Fashion in the Twenties and Thirties, Ian Allan Ltd., 1973

Dorner, J., Fashion in the Forties and Fifties, Ian Allan Ltd., 1975

Duff Gordon, Lady (Lucile), Discretions and Indiscretions, Jarrolds, 1932

Fairchild, John, The Fashionable Savages, Doubleday & Co. Inc., 1965

Fashion 1900–1939, Exhibition Catalogue, Scottish Arts Council & V & A, 1975

Forbes-Robertson, Diana, Maxine, Hamish Hamilton, 1964

Garland, Madge, Fashion, Penguin Books, 1962

Garland, Madge, The Changing Form of Fashion, J. M. Dent, 1970

Garland, Madge, The Indecisive Years, Macdonald, 1968

Glynn, Prudence, In Fashion, Allen & Unwin, 1978

Greer, Howard, Designing Male, Robert Hale, 1952

Halliday, Leonard, The Makers of our Clothes, Zenith Books, 1966

Hartnell, Norman, Silver and Gold, Evans Bros., 1955

Howell, G., In Vogue, Condé Nast Publications, 1975

Huggett, Renée, Shops, Batsford, 1969

Jarrow, Jeannette A. and Jondelle, Beatrice, Inside the Fashion Business, John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1965

Jefferys, James B., Retail Trading in Britain, 1850–1950, Cambridge University Press, 1964

Journal of the Costume Society, 1967–1985

Kennett, F., A Collector’s Book of Twentieth Century Fashion, 1983

Keppel, Sonia, Edwardian Daughter, Hamish Hamilton, 1958

Lambert, Richard B., The Universal Provider, A Study of William Whitely and the Rise of the London Department Store, Harrap, 1938

Laver, James, Costume, Cassell, 1963

Laver, James, Costume and Fashion, (new ed.) Thames and Hudson, 1982

Laver, James, Taste and Fashion, Harrap, 1937

Laver, James, Women’s Dress in the Jazz Age, Hamish Hamilton, 1964

Mackrell, Alice, Paul Poiret, Batsford, 1990

Mackrell, Alice, Coco Chanel, Batsford, 1992

McDowell, C., McDowell’s Directory of Twentieth Century Fashion, Muller, 1984

de Marly, Diana, The History of Haute Couture 1850–1950, Batsford, 1980

de Marly, Diana, Christian Dior, Batsford, 1990

Mayer, Mrs. Carl and Black, Clementina, Makers of our Clothes, Duckworth, 1909

Maugham, W. Somerset, Bondage, Heinemann, 1915; Re-issued as Of Human Bondage, 1934

Poiret, Paul, My First Fifty Years, Gollancz, 1934

Pound, Reginald, Selfridge, Heinemann, 1960

Priestley, J. B., The Edwardians, Heinemann, 1970

Pritchard, Mrs. Eric, The Cult of Chiffon, Grant Richards, 1902

Quant, Mary, Quant by Quant, Cassell, 1966

Raverat, Gwen, Period Piece, Faber and Faber, 1952

Rees, Goronwy, St. Michael. A History of Marks and Spencer, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1969

Saunders, Edith, The Age of Worth, Longmans Green, 1954

Schiaparelli, Shocking Life, J. M. Dent, 1954

Settle, Alison, A Family of Shops, Marshall & Snelgrove

Settle, Alison, English Fashion, Collins, 1959

Settle, Alison, Fashion and Trade, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 1970

Spanier, Ginette, It isn’t all Mink, Collins, 1959

Spanier, Ginette, And now it’s Sables, Robert Hale, 1970

Stewart, Margaret and Hunter, Leslie, The Needle is Threaded, Heinemann/Newman Neame, 1964

The Present Position of the Apparel and Fashion Industry, A Report, AFIA 1950

The World in Vogue, 1893–1963, Condé Nast Publications, 1963

Tweedsmuir, Susan, The Edwardian Lady, Duckworth, 1966

Waugh, Norah, The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600–1930, Faber & Faber, 1968

Westminster, Loelia Duchess of, Grace and Favour, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1961

White, Cynthia, Women’s Magazines, 1693–1966, Michael Joseph, 1970

Wilcox, R. Turner, Five Centuries of American Fashion, A. & C. Black, 1963

Wilkinson, Marjorie, Clothes, Batsford, 1970

Wray, Margaret, M.A., Ph.D., The Women’s Outerwear Industry, G. Duckworth, 1957

Yarwood, Doreen, Encyclopaedia of World Costume, Batsford, 1978

Yarwood, Doreen, English Costume, Batsford, Fifth Edition, 1979

York, P., Style Wars, Sidgwick, 1980

Yoxall, Harry, A Fashion of Life, Heinemann, 1966

The Illustrations

Unacknowledged photographs are from publisher’s archives.

1 Fashion dictated by High Society (Victoria & Albert Museum)

2 A Mirror to Life (Mansell Collection)

3 La Belle Epoque (Museum of Costume, Bath)

4 ‘Extravagance was the prevailing mood’ (Victoria & Albert Museum)

5 ‘The daunting elaboration’ (Victoria & Albert Museum)

6 Dressed for the country (Mansell Collection)

7 Formality for the country week-end (Mansell Collection)

8 Queen Alexandra (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

9 A perpetual summer (Victoria & Albert Museum)

10 The S-shaped corset (Mansell Collection)

11 ‘A large overhanging bust’ (Mansell Collection)

12 Hats (Marshall & Snelgrove)

13 Spring fashions for walking (Marshall & Snelgrove)

14 Tea-gown (Mansell Collection)

15 Tea-gown (Liberty/Museum of Costume, Bath)

16 Fashions at a Paris Exhibition (Mansell Collection)

17 Eva Moore (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

18 Maxine Elliott (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

19 Lily Langtry (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

20 The New Woman (Victoria & Albert Museum )

21 The tailor-made and the bicycle (Burberrys)

22 Real-life New Woman (Supplied by author)

23 Costumes (The Lady)

24 The sportswoman (The Lady)

25 Evening blouses (The Lady)

26 Blouses (Swan & Edgar)

27 The Gibson Girl (Mansell Collection)

28 Camille Clifford (Mansell Collection)

29 Trimmings and Accessories (Swan & Edgar)

30 Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon (Mansell Collection)

31 Lily Elsie (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

32 Evening dress and hat (The Lady)

33 Swan & Edgars in 1927 (Swan & Edgar)

34 ‘Robes (unmade)’ (Swan & Edgar)

35 Harrods in 1909 (Harrods/Museum of Costume, Bath)

36 Shopping for pleasure (Debenham & Freebody )

37 Department of Harrods (Harrods)

38 New coat for the woman golfer (Burberry s)

39 The Amazon and the Viator (Burberrys)

40 The car paletot (Burberrys)

41 Fashion went to the head (Burberrys)

42 Made to measure (Burberrys)

43 Invitation to Selfridges (Selfridges)

44 Selfridges in 1931 (Selfridges)

45, 46 Selincourt Fashions (Selincourt)

47 Exclusive fashions (Victoria & Albert Museum)

48 Sweated workers in fashion (Popperfoto)

49 The sordid side of fashion (Popperfoto)

50 The beautiful blouse (Marshall & Snelgrove)

51 Rustling petticoats (The Lady)

52 Dress by Paul Poiret (Mansell Collection)

53 The new corset (Museum of Costume, Bath)

54 The hobble skirt (Mansell Collection)

55 Away from frills and flounces (Museum of Costume, Bath)

56 Pleats eased the hobble skirt (Victoria & Albert Museum)

57 A slit also brought freedom (Museum of Costume, Bath)

58 Off-the-ground skirts (Marshall & Snelgrove)

59 Evening dress by Worth (Victoria & Albert Museum

60 Evening dress by Mascotte (Victoria & Albert Museum

61 Tunic dress (Victoria & Albert Museum)

62 Summer dresses from Butterick Patterns (Museum of Costume, Bath)

63 Tunics in fashion (The Lady)

64 Draped skirt and ‘trotteur’ at Longchamps (Mansell Collection)

65 Hat fashions (The Lady)

66 Hats become bigger (Museum of Costume, Bath)

67 Croquet in 1910 (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

68 Golfing in 1910 (Aquascutum)

69 Mrs. Sterry (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

70 The sports coat came in (Marshall & Snelgrove)

71 Ascot, 1914 (The Lady)

72 Mr. and Mrs. Vernon Castle (Popperfoto)

73 Fashions of 1915 (Debenham & Freebody)

74 Tea-gown of 1915 (Debenham & Freebody)

75 A sudden change to full skirts

76 Shapeless clothes of 1915 (Marshall & Snelgrove)

77 Woman munition worker (Popperfoto)

78 Edinburgh women tram conductors (Mansell Collection)

79 Sports coats (Swan & Edgar)

80 Paris fashions for 1916 (Museum of Costume, Bath)

81 Evening dress (Marshall & Snelgrove)

82 Elaborate boots and shoes (Swan & Edgar)

83 River girls in gay frocks (Swan & Edgar)

84 Tunic skirt of 1918 (The Lady)

85 Elegance in velvet (The Lady)

86 The coat frock (Debenham & Freebody)

87 Rayon comes into fashion (Courtaulds)

88 Short evening dress (Victoria & Albert Museum)

89 End of war fashions (The Lady)

90 Shorter skirts (Victoria & Albert Museum )

91 Ready-to-wear coats and skirts (Marshall & Snelgrove)

92 Skirts fell in 1923

93 Sleeveless jumper with hip belt (Debenham & Freebody)

94 No curves in the ’twenties (Victoria & Albert Museum)

95 Short skirts of 1928 (Victoria & Albert Museum)

96 Variety in fashions

97 Suzanne Lenglen (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

98 Embroidered evening dress (Victoria & Albert Museum)

99 Evening dress with dipping hem (Debenham & Freebody)

100 Fashion scene (Marshall & Snelgrove)

101 The cloche hat (Marshall & Snelgrove)

102 Pearls in all sizes (Museum of Costume, Bath)

103 Greta Garbo (National Film Archive)

104 Paris trends (Museum of Costume, Bath)

105 Gabrielle Chanel (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

106 Worth evening gown (Victoria & Albert Museum)

107 Worth’s shorter skirt (Museum of Costume, Bath)

108 Paris models copied by the stores (Marshall & Snelgrove)

109 The longer look (Swan & Edgar)

110 A 1930 ensemble (Marshall & Snelgrove)

111 The more feminine look ( Swan & Edgar)

112 Natural waist and longer skirts (Marshall & Snelgrove)

113 Backless evening dress (Marshall & Snelgrove)

114 Paris evening dresses (Museum of Costume, Bath)

115 Daytime styles from Paris (Museum of Costume, Bath)

116 Fox furs in favour (Bradleys Furs)

117 Fantasy in Fox, by Erté

118 Beach pyjamas (Swan & Edgar)

119 Beach and holiday fashions (Jaeger)

120 Mainbocher evening dress (Cecil Beaton/Victoria & Albert Museum)

121 Schiaparelli evening dress and cape (Cecil Beaton/Victoria & Albert Museum)

122 Built-up shoulders by Worth (Museum of Costume, Bath)

123 Sweater by Schiaparelli (Cecil Beaton/Victoria & Albert Museum)

124 Hat, jacket and necklace by Schiaparelli (Cecil Beaton/Victoria & Albert Museum)

125 Inexpensive dresses (Marshall & Snelgrove)

126 Ready-to-wear evening dress (Debenham & Free body)

127 Ready-to-wear fashion (Marshall & Snelgrove)

128 Popular fashions of 1935 (Swan & Edgar)

129 Holiday styles (The Lady)

130 Joan Crawford (National Film Archive)

131 Inexpensive fashion (Swan & Edgar)

132 Copy of a Paris model (Debenham & Freebody)

133 A three-piece of 1933 (Dorville)

134 A tea-gown of 1930 (Debenham & Freebody)

135 Cardigan suit (Debenham & Freebody)

136 Dress and coat in lace

137 Elegance in ready-to-wear in 1938 (Bradleys)

138 Knitwear designs for 1937 (Marshall & Snelgrove)

139 Rodex coats of the early 1930’s (Aquascutum)

140 Tailored fashions (Jaeger)

141 Inexpensive dresses of 1934 (Swan & Edgar)

142 Summer fashions (The Lady)

143 Women ambulance drivers (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

144 Nurses and air raid wardens (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

145 A.T.S. uniforms (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

146 Land girls, 1941 (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

147 Utility suit and blouse (Victoria & Albert Museum )

148 A wartime fashion show (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

149 Non-Utility styles of 1943 (Marshall & Snelgrove)

150 Wartime Utility suit (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

151 Head scarves (Marshall & Snelgrove)

152 Do it yourself fashion (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

153 Utility suit (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

154 Utility fashions of 1945 ( Marshall & Snelgrove)

155 An American suit of 1945 (Museum of Costume, Bath)

156 Afternoon dress by Norman Hartnell (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library)

157 Designs for 1956 (Frederick Starke)

158 Television fashion in 1946

159 Dior’s New Look cocktail dress (Cecil Beaton/Victoria & Albert Museum)

160 The New Look in ready-to-wear (Lou Ritter)

161 Dress by Worth (Victoria & Albert Museum)

162 Coat by Hardy Amies ( College of Fashion & Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

163 Dress in tartan wool (College of Fashion & Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

164 Coat by Victor Stiebel (College of Fashion & Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

165 Elegance by Worth (Museum of Costume, Bath)

166 Dior dress, 1966 (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

167 Balenciaga evening dress (Cecil Beaton/Victoria & Albert Museum)

168 Balenciaga evening skirt and blouse (Cecil Beaton/Victoria and Albert Museum)

169 Suit by Norman Hartnell (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

170 Dress, 1948 (Frederick Starke)

171 Grey flannel middy suit (Dorville)

172 Suit, 1955 (Frederick Starke)

173 Suit, 1958 (Frederick Starke)

174 Summer fashions (Marshall & Snelgrove)

175 Suits of 1953 (Marshall & Snelgrove)

176 Suit by Ronald Paterson (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

177 Jane Russell and the ‘Sweater girl’ bra (Popperfoto and Truline sketch)

178 Dirndl dress (Marshall & Snelgrove)

179 Full skirted dress (Frederick Starke)

180 Short evening dress by Roter (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology)

181 Evening casuals from Italy (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

182 Casuals by Cole of California (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology)

183 Chunky sweater and slacks (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

184 Chunky sweater (Dorville)

185 Sweater dress by John Carr Doughty (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology)

186 Stiletto shoes (Victoria and Albert Museum)

187 Trendy fashion (Du Pont)

188 Designs of the late ’fifties (Mary Quant)

189 Spring suit by Hardy Amies (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

190 Maxi coat (Alexon Youngset)

191 Dresses and pants (Mary Quant Ginger Group)

192 Young fashions (Popperfoto)

193 Dior shorts (Popperfoto)

194 Culotte dress (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

195 Flattering clothes (Marshall & Snelgrove)

196 Fashion parade at Covent Garden Opera House (Sunday Telegraph)

197 Coat by Hardy Amies (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

198 Evening dress by Norman Hartnell (Museum of Costume, Bath)

199 Ball gown by John Cavanagh (Museum of Costume, Bath)

200 Export fashions of the ’fifties (Frederick Starke)

201 Fashion House Group Spectacular (Michael Whittaker)

202 Young designers with winning fashions

203 British fashion in Paris

204 Space age fashion by Cardin (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

205 Courrèges dress (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

206 Suits by Patou (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

207 Blazer and skirt by Yves St. Laurent (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

208 Coat by Heim (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

209 Dress by Cardin (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

210 Plastic coat and linen dress (Museum of Costume, Bath)

211 Hot pants (Popperfoto)

212 Dress by Jean Muir (Museum of Costume, Bath)

213 Pants dress by Ossie Clark (Museum of Costume, Bath)

214 Trouser suit (Frank Usher)

215 Evening dress (Frank Usher)

216 Coat (Harella)

217 Jerkin and trousers (Harella)

218 Trouser suit (Linda Leigh)

219 Dress and jacket (Alexon)

220 Cotton piqué suit (Alexon)

221 Fashion parade (Eastex)

222 Fashions of 1972 (Eastex)

223 Raincoat (Aquascutum)

224 Swing-back coat (Aquascutum)

225 Trench coat (Burberrys)

226 The Berkertex factory (Berkertex)

227 Dress and jacket (Berkertex)

228 Shirtwaister (Berkertex)

229 Cresta shop within a shop (Cresta)

230 Early advertisement for Celanese (Courtaulds)

231 Dress by Shubette (Courtaulds)

232 Shirt by Brettles (Courtaulds)

233 Coat by Venet (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

234 Suit by Bonnie Cashin (Liberty)

235 Coat by Bonnie Cashin (Liberty)

236 Trouser suit (Du Pont)

237 Cocktail dress (Du Pont)

238 Hostess dress (Horrockses Fashions)

239 Co-ordinates (Alexon)

240 Three-piece by Act III (Du Pont)

241 Jump suits and coats by Lanvin (Du Pont)

242 Top and skirt and long-sleeved dress (Frank Usher)

243 Bloomers suit (Mary Quant)

244 Hand-printed evening dress (Frank Usher)

245 Midi coat by Rosewin (Du Pont)

246 Party Dress (Du Pont)

247 Evening separates (Jaeger)

248 Pants suit and skirt (Du Pont)

249 Smock and suits (Mary Quant)

250 Chanel suit (College of Fashion and Clothing Technology/International Wool Secretariat)

251 The ’thirties look

252 Balmain evening dress

253 Coat-dress by Ungaro (I.W.S.)

254 Coat and skirt by Sonia Rykiel (I.W.S.)

255 The casual look in fashion (I.W.S.)

256 Dress of the year 1981 (Lagerfeld; Bath Evening Chronicle))

257 Karl Lagerfeld three-piece ensemble (I. W.S.)

258 Dress of the year 1977 by Kenzo (Fashion Research Centre, Bath)

259 Denim 1974

260 Denim 1982

261 Punk influence in 1985

262 Dance dress by Frank Usher

263 Lacy two-piece by Frank Usher

264 Navy blazer and cream skirt by Aquascutum

265 Slick city-suit by Aquascutum

266 Black two-piece by Deréta

267 Casual wear by Deréta

268 Striped two-piece by Windsmoor

269 Swashbuckling summer outfit by Windsmoor

270 Co-ordinated separates by Planet

271 Grey flannel suit with toning blouse (Alexon)

272 Polyester/wool coat-dress by Jaeger

273 Cotton styles for winter by the International Institute for Cotton

274 Tsarina coat and quilted trousers (Du Pont)

275 Leotard and footless tights by Du Pont

276 Dress of the Year 1987, designed by John Galliano (Museum of Costume, Bath)

277 Bow trapeze dress, Autumn/Winter 1991 (Ben de Lisi, London)

278 Casual co-ordinates from Windsmoor’s Designer Collection

279 Summer separates by Planet

280 Winter coat by Guy Paulin

281 Jean Muir collection, 1981

282 City suit. Jaegar Man Spring Collection 1986 (Westminster City Archives, London)

283 Parka, leggings, T shirt and suede lace-up boots, Autumn/Winter 1991 (Next Press Office, London)

284 Jacket and skirt, suede mid-heel court shoes and a selection of jewellery, Autumn/Winter 1991 (Next Press Office, London)

285 Cricket blazer, wool skirt and straw boater, 1991 (Marks & Spencer, London)

286 Velvet bodysuit, January 1992 (Marks & Spencer)

287 Ensemble, 1986 (Laura Ashley, Maidenhead, Berkshire)

288 ‘Rebecca’ by Aquascutum, Spring 1989 (Aquascutum, London)

289 Dress of the Year 1986, designed by Giorgio Armani (Museum of Costume, Bath)

290 Dress of the Year 1990, designed by Romeo Gigli (Museum of Costume, Bath)

291 Dress of the Year 1988, designed by Jean Paul Gaultier (Museum of Costume, Bath)

292 Bold graphics for the 90’s (Bill Blass Ltd)

293 Haute couture dress, Spring 1991 (Victor Edelstein, London)

294 Chic Survival (Carmelo Pomodoro Ltd)

295 Duffle up! (Carmelo Pomodoro Ltd)

296 Top and long johns, Autumn/Winter 1990 (Triumph Internatinal)

297 Lace and velour bodysuit, 1990–91 (Marks & Spencer, London)

298 Natalia Bashkatova wearing garments made of Tactel designed by Nicole Farhi, 1991 (Heather Tilbury Associates, London)

299 Sporty outfit symbolic of the early 1990’s

300 Suit, Spring 1989 (Ralph Lauren)

301 ‘Prairie look’, Spring 1989 (Ralph Lauren, London)

302 Fashion sketches, 1990/91 (Robert Best)

303 Evening dress (Solonge)

304 Day outfit, Autumn/Winter 1990/91

305 Cashmere, Spring/Summer 1991 (Hanae Mori)

306 Biker clothes, Summer 1991 (Ogan/Dallal Associates)

307 Hooded anorak, Spring 1990 (Restivo Sport)

1 Fashion dictated by High Society–1900

1 Edwardian sunshine for the few, but change in the air, 1900–1909

1

Within the span of this century fashion has changed in everything but name. What had always been the special preserve of the privileged few has become the happy hunting ground of all. Long-treasured traditions of hand craftsmanship, with their slow, infinitely patient methods of making-up, which put fashion out of reach of most people, have in the main been superseded by large-scale manufacture primed with growing expertise and catering for all sections of the consumer market. Fashion now pours off the production lines of innumerable substantial factories and is being reproduced with the technical know-how of a modern work force that numbers hundreds of thousands in nearly every leading Western country and far beyond. Fashion is a vast industry – in New York, the world’s largest city, it is the largest of all. In Paris, for centuries the centre of fashion creation, haute couture rubs shoulders with an ever-expanding ready-to-wear trade even within the enclaves once sacred to the jealously guarded elegances of la mode. Fashion is no longer dictated by High Society ; as often as not it is triggered off and swept into favour by the anonymous but compulsive force of this or that section of the masses. It is news. It moves under a constant floodlight of publicity.

How this has happened and what events and people have been the main contributors to it is a story that has no parallel from the past. It would be against all reason if there were. ‘Fashion is the outward and visible sign of a civilisation, it is part of social history’, says Amy Latour in Kings of Fashion. The civilisation and the social history of the twentieth century have swept right out of the context of previous times. The new look that science, industrial development, technology and social and economic changes have given to nearly every aspect of daily life has rubbed off on fashion which, as one of the arts mineurs, has always held up its own mirror to life, reflecting not only basic attitudes and their changes but also playing on lesser variations with something like the momentary flicker of sunlight on water. It is doing all this today, but, in addition, its structure and even its entity have progressively changed in a way that has no precedent.

2 A Mirror to Life in 1903

Fashion, unless we are going to be very anthropological about it, dates from the time when, about 1300, people in the Western world stopped wearing the various kinds of loose hanging or draped robes which, with little basic change, had served them as clothing all over the world through practically all civilisations, and began to wear fitted clothes. These immediately showed signs of acquiring a history and almost a life of their own. They changed continually, though at varying rates of speed, borne along by an impetus whose source has been the subject of endless enquiry and speculation. The trouble is that no one’s findings have ever wholly satisfied anyone else. Fashion was not. Fashion came; could it also go?

To start with, and for a considerable period, fashion applied equally to the clothes of men and women. In medieval, Tudor and Stuart times and even for much of the eighteenth century man was often the proud peacock who outshone the contemporary lady. But in more recent times fashion has come to be generally accepted as applying to women’s dress and this is the meaning to be given to it here – although the trend of the recent ’sixties and the present ’seventies threatens to reverse use and wont and dazzle the world again with male and female – and, for good measure – unisex fashions.

One immutable feature of fashion up to this century was that it was dictated from the top. The ruling classes – which meant the Court or some aristocracy of rank or wealth – made fashion. They were its accepted, unquestioned leaders, and from them it spread downwards. The descent was usually fairly slow and it never reached anything like the whole of the community. Fashion was a minority movement. When William Hazlitt said in an essay on the subject: ‘Fashion is an odd jumble of contradictions, of sympathies and antipathies. It exists only by its being participated among a number of persons and its essence is destroyed by being communicated to a greater number,’ he stated what was true in the early nineteenth century. The very meaning of fashion implies freedom to follow it and for the majority of people such freedom did not exist in Hazlitt’s time. If a fashion spread to the masses it would not be at their choice and would therefore not be a ‘fashion’ any more. A century and a half later Dr. Willett Cunnington made this point when he said: ‘So long as there is not a free choice of style of dress, we cannot correctly speak of a “fashion” at all.’ But at this time, 1951, he continued: ‘Fashion is established only when adopted by the millions, instead of by the hundreds.’ Free choice then existed for all. Sir Cecil Beaton, speaking for the ’seventies, sums it up more succinctly : ‘Fashion is a mass phenomenon, but it feeds on the individual.’ There must be personal originators and when they are followed you have fashion.

Today, accordingly, fashion is for all. Couturiers, speciality shops, department stores, boutiques, chain stores and multiples all offer fashion. In contrast to the past the biggest and the less expensive outlets are even on occasion the most fashionable. It is difficult to realise that at the start of this century millions of women, including a considerable proportion of middle class ones, had no means by which they could follow fashion without endless trouble and contrivances and waste of time. But the writings of the time show that it was so. The spread of fashion, and its availability, moved pace by pace with the emancipation of women, but both moved slowly and laboriously.

3 La Belle Epoque, 1905

4 ‘Extravagance was the prevailing mood of Society’. 1900

5 The daunting elaboration of her toilette. 1900

At the start of the twentieth century there was little surface indication of any change in the traditional pattern of fashion for the few. Never had fashion as an expensive, class-conscious spectacle had such a heyday. In France it was la Belle Epoque and the name was a tribute to the fashions which flourished there in an extravagance of silks and satins, ribbons and laces, flowers and feathers and jewels, making Paris more than ever before the Mecca of fashion for all the world. America, closely linked with Europe since colonial days, followed Paris closely, with the more wealthy of the fashion-seekers selecting their wardrobes on personal visits, while many others followed Paris’s lead through the acquisition of original models or copies obtained from there by the top flight of ‘little’ – or not so little – dressmakers in their American home towns.

In Britain the Gay Nineties were being followed by the Establishment-style gaiety and splendour of Edwardian days. The shining, almost theatrical allure which was part of this neardecade finds no more apt symbol than the fashionable lady. ‘Extravagance,’ says Alison Adburgham, ‘was the prevailing mood of Society, with mature and triumphant womanhood the focus of all glory, laud and bonheur.’ That it was the calm before the storm gives the period in retrospect a lingering, nostalgic quality that is hard to resist. ‘Edwardian high society,’ J. B. Priestley comments, ‘added a little chapter, and surely . . . the last, to the myth of the lost Golden Age.’ And he is no dreamer.

Fashion was securely controlled by the rich and socially eminent among the upper classes and by those who had achieved wealth and the limelight of either fame or notoriety, plus the copious leisure that being in fashion still demanded. Fashion was a badge of social status and its devotees regarded it with high seriousness and full absorption. Fantastic, elaborate, shaped as nature never made her, the fashionable Edwardian lady is infinitely beguiling in the aplomb and serenity with which she carries off the daunting elaboration of her toilette. Those immense, yard-wide hats, laden with plumes and feathers or with basket-loads of artificial flowers ; those rustling, frothing bell-shaped skirts that swept the ground; that giddy confusion of ribbons, lace, embroidery, frills, jewels and beads at every point all contributed to fashion’s mighty overspill. Clothes like these were to disappear about 1908 – for what we call the Edwardian age really started before the end of the nineteenth century and was in eclipse before the end of Edward VII’s reign. Nothing like these fashions has been seen since then, nor is it likely to be, but she was blissfully unaware, the Edwardian lady, that hers was a sunset song and that, even in her own time, she was becoming an anachronism.

6 Dressed for the country. 1901

7 Formality for the country weekend. 1904

The fashionable world, to which she belonged, revolved round the Court which, under the new King, had an importance unparalleled since then. It included new elements which contributed to its luxury and elegance. Beautiful and wealthy American women, most of whom had married into the British peerage, were brought into prominence by the King, among them Lady Ribblesdale, Lady Granard, Lady Cunard, Lady Curzon (Mary Leiter), Lady Astor and Consuelo, Duchess of Marlborough (later Madame Jacques Balsan). There were also some notable figures in Court circles who were interlopers from finance and even trade, but they all played the game according to the traditional code. This covered nearly every facet of daily life. It enjoined great formality and immense luxury in women’s dress and also demanded close attention to being in the height of fashion and to wearing the correct clothes on all occasions. On the famous week-end country visits, which were a feature of high life, the fashionable lady would change her dress, with all its accessories, five or six times a day. And no outfit should be seen twice during one week-end. Several trunks and immense hat boxes were normal luggage for these visits, with, of course, an attendant lady’s maid to manoeuvre the panoply of fashion for its high priestess – or victim.

This was the inescapable ambience of fashion and the blueprint of all who aspired to it in the early years of this century. The clothes for the top ladies of the time came from many dressmakers. Paris was, however, dominant. ‘It was the fashion to be dressed by Paris couturiers Worth, Redfern and Callot,’ declared American Vogue, and London thought likewise. The hypnotic spell Paris cast on the fashion scene was all-embracing. Paris was a magic word. ‘Paris model,’ ‘copy of a Paris model’, these and similar phrases were echoed beguilingly wherever fashion was mentioned. London was, however, beginning to sustain a cluster of outstanding dressmakers who were flourishing in their own right and, though many of them depended upon Paris’s lead, some of them were challenging the time-honoured monopoly and were themselves to become international figures. Though many of the most elegant Englishwomen shopped regularly in Paris, there was also developing a patriotic trend to buy British. This was given a lead by Queen Alexandra, both during her reign and previously as Princess of Wales. ‘For patriotic reasons she dressed chiefly in London,’ says Georgina Battiscombe in her life of the Queen, ‘where her favourite dressmaker was Redfern, but occasionally she allowed herself a shopping expedition to Paris. There she would patronise Doucet, then a great name in the world of fashion, also the lesser known Fromont, of the Rue de la Paix.’ She had also been known to buy from Worth.

8 Queen Alexandra, last Royal fashion leader, in 1905

Queen Alexandra was a lifelong maker of fashion – the last Royal lady and indeed the last great lady to achieve this eminence and to give fashion a leadership and quality it has lacked ever since. She was a magnificent figure. In 1909 Lady Oxford described how ‘the Queen, dazzlingly beautiful, whether in gold and silver by night, or in violet velvet by day, succeeded in making every other woman look common beside her’. She was ‘lovely and gracious, ineffably beautiful’, and, again, ‘slender, gracious and beautiful’. She was then 64. Where fashion was concerned Queen Alexandra was also, like other great ladies of her time, a leader with a mind of her own. Of her Coronation attire she wrote to Sir Arthur Ellis: ‘I know better than all the milliners and antiquaries. I shall wear exactly what I like and so will all my ladies. Basta!’

This royal explosion of defiance was in key with the past, when great ladies would dictate to their chosen dressmakers and on occasion turn their private inspirations and ideas into fashion. But it was also in key with a certain relaxation of rigidity and solemnity which was making itself felt in fashionable life as the twentieth century got under way. ‘In this new sunshine did the metamorphosis of taste take place overnight, I wonder?’ queries Sonia Keppel in Edwardian Daughter. ‘Suddenly,’ she recalls, ‘all Victorian furniture, ottomans, antimacassers &c all disappeared, with Turkey pile, dismal reps. In came chaises-longues, papier maché chairs, lace curtains, midget tables, nebulous colours. . . . Whereas, in Queen Victoria’s reign paterfamilias predominated and male taste prevailed, now in King Edward’s reign, the deification of the feminine was re-established.’

9 A perpetual summer. 1905

10 The S-shaped corset, introduced in 1900, claimed to follow the natural lines of the figure

This deification meant that more attention was given to fashion, which also developed a number of new characteristics. Stiff satins, plush, damask, tweed and rigid materials in general went out with other Victoriana, and in came a froth of chiffons and laces, net and ninon, soft faille, tussore, crêpe de Chine, mohair and cashmere. Strong, emphatic or sombre colours were superseded by sweet pea and sugar almond delicacies of tone. Frills, beading, ribbons and trimmings of all sorts ran riot over the fashionable clothes of the time. ‘The upper classes of Europe had succeeded in establishing for themselves a perpetual summer, and this fact was reflected in women’s dress,’ says James Laver of this time. And where the upper classes led others were by now trying hard to follow.

While the elegant, leisured Edwardian woman was setting the fashion scene with these light and airy dresses she was, however, wearing under them a corset that was anything but light and airy and which gave her one of the most extraordinary and constricting shapes that exist in fashion’s annals. The famous ‘S’-shaped figure of the time was the result of a new corset introduced in 1900. It was invented by a Frenchwoman, Mme. Gaches-Sarraute, who had studied medicine and whose aim was to create a foundation garment which would benefit the health of women by removing the extreme pressure exerted on the waist and diaphragm by the prevalent style of corset. This came high up on the bust and had a curved front busk indented at the tightly laced-up waist. The new design had a straight busk, began lower down on the bosom, which it released, and extended more deeply over the hips. It was named the Health Corset, and it should have lived up to its name, but unfortunately the idea went wrong. The fashionable Edwardian lady did not want to follow nature. The corset was laced up tightly over the large, mature Junoesque curves that were fashion’s ideal, for the age of a mature king was also the age – the last – of the mature woman. This corset forced the bosom forward and thrust the hips back, thereby producing what became known as the ‘kangaroo stance’ as well as the ‘S’ line. The fashionable shape therefore consisted of a large, overhanging bust, augmented, if nature was sparing, by a heavily frilled or even boned camisole or bodice, which even, on occasion, included handkerchiefs used as stuffing. The blouse or dress top was pouched lavishly over this. The forward flow of the bosom and the tight waist were counterbalanced by a majestic sweep of curving hips and derrière, outlined by a bellshaped skirt, a shape new to fashion. The effect was as if the top of the lady was a foot ahead of the rest of her. The skirt fitted closely to the figure to below the hips, then flared to the ground, usually trailing on it and even by day sometimes completed by a train. Various kinds of clips were used to keep it off the ground out of doors.

11 A large, overhanging bust. 1903

12 Hats were perched on top of elaborate hair styles, 1906. These were devised for motoring, travelling, walking and for elegant occasions respectively

The general pattern of formal fashion changed very little between 1900 and about 1908. A great many clothes were worn – chemise, corset, corset cover, drawers, a flannel petticoat, one or more cotton petticoats and, to be really elegant, a silk one over all. Large, forward-sweeping hats balanced the rear projection of the figure. Hair was puffed out and built up over pads inserted along the front of the head. These were known as ‘rats’ and persisted through the first decade of this century and to some degree after that. The back hair was drawn up and supported by combs. Hats were perched on this contraption of hair-styling and secured to it by means of long hat-pins, often with elaborate jewelled or enamelled heads, which speared the hat to the hair. Often they had lethal projecting points which menaced anyone who approached the wearer too closely.

13 Spring fashions, 1906, for walking

Fashionable hats could be enormously expensive, as much as 50 guineas being not unusual, but the costly ostrich feathers, aigrettes, osprey feathers and other feathered or floral embellishments would be transferred from one hat to another. Hats were always worn, for sport and even by children at play. Other elaborate items contributed to the fashionable toilette. Chief of these were ostrich or marabou boas and stoles and, for colder weather, long fur stoles and large pillow-shaped muffs. Parasols were part of the summer ensemble: ‘Women of fashion require many parasols during a London season,’ says a fashion writer of 1902. Jewellery was worn in great profusion and was a costly item. But a signpost for the future appeared in the Illustrated London News when, in a fashion article in 1904, it drew its readers’ attention to the Parisian Diamond Company’s artificial jewellery, which could be invaluable ‘for the succour of those whose worldly wealth will not extend to the limitless thousands that modern fashion desires to spend on pearls and diamonds alone’.

The epitome of elegance at this time and for many years to come was the tea-gown. It was to become a garment of mystery to future generations, but it symbolised the vanishing world. ‘In our own drawing rooms,’ rhapsodises Mrs. Eric Pritchard in The Cult of Chiffon in 1902, ‘when the tea-urn sings at five o’clock, we can don these garments of poetical beauty.’ The tea-gown is also ‘this garment of mystery which can be a very complete reflection of the wearer’. Going into details, she describes ‘the ideal tea-gown of accordion pleated chiffon, lace and hanging stoles of regal furs’. Gwen Raverat, writing of the same time, recalls that her mother ‘was in her glory in a tea-gown’. Susan, Lady Tweedsmuir describes her cousin Hilda Lyttleton’s appearance ‘wearing tea-gowns made by the Italian dress designer Fortuny, whose fanciful but lovely dresses were all the rage in these days. He made for her long straight garments of artfully pleated satin, held at neck, wrists and waist by strings of small iridescent shells.’ Lady Diana Cooper remembers that, about the time when she ‘came out’ in 1911, ‘the ladies dressed for tea in trailing chiffon and lace, and changed again for dinner into something less limp’. Top stores also specialised in tea-gowns. Debenham & Freebody said in a 1908 catalogue: ‘We have made a special study of Rest, Boudoir and Tea-Gowns, and have now in stock a wonderful variety of these dainty and useful garments. These gowns are our own exclusive design, and are made in our own workrooms from materials that we can thoroughly recommend’. Marshall and Snelgrove in colour catalogues of the same period illustrated some spectacular tea-gowns. There was, for instance, ‘Clytie’, which was created in ivory satin, veiled with shadow lace, with a narrow insertion of Wedgwood ninon, finished with tiny vieux rose buttons. The coat effect, in a rich quality painted gauze ribbon and ninon to tone. Price 15 guineas.’ ‘Delphine’ was another prized design, ‘in satin with tunic of silk, voile and guipure lace, made to order 15 guineas’. The tea-gown lingered on. In spite of the new outlook and new way of life which resulted from World War I, stores still featured it in 1919 and through the ’twenties, though by then it was being replaced by the afternoon gown and the cocktail dress, symbols of a new and different world.

14 Tea gown in black satin and chiffon, 1901

2

The suggestion that there was hope for those who wanted to be in fashion but could not keep up with it on the scale set by its accepted wealthy leaders was being made increasingly in the ‘glossy’ magazines of the early nineteen-hundreds. Keeping up with fashion had become a matter of considerable concern to a substantial and growing section of the female members of the rising, prosperous middle classes and also of anxiety and neardespair to the not-so-wealthy elements of this group. Living up to one’s ‘position’ was terribly important. Ways of achieving the fashionable look on a shoe-string budget were a major preoccupation. The fashionable Edwardian lady was, unknown to herself, the tip of an iceberg of which the huge base was beginning to be visible and significant as the fashion followers increased.

15 The tea gown lingered on—this 1916 version is in silk crepe and lace, with embroidery

The foundations upon which Edwardian fashion flourished and also one important means by which it was being extended had been laid in the previous half-century in Paris, but paradoxically, by an Englishman, Charles Frederick Worth. He was to Paris fashion what the Emperor Augustus was to Rome. He not only built a brilliant fashion empire of his own but also, although he may not have foreseen all the consequences, he put fashion on a new basis which led in the direction of fashion for all and he opened the way for the immense changes and developments which were to come.

Worth was born at Bourne, in Lincolnshire, in 1825, the son of an unsuccessful lawyer, and after starting work at the age of 12 in a local draper’s shop, he went to London as an apprentice at Swan and Edgar’s small, elegant shop in Piccadilly, where he served behind the counter, selling shawls and dress materials. In 1845 ambition took him to Paris where, at the fashionable Maison Gagelin, he was soon selling fabrics and also cloaks and mantles – the ‘confections’ which were among the first steps towards ready-made women’s fashions. In 1858 he set up his own dress house. Paris fashion design, then mainly in the hands of undistinguished women dressmakers, had lapsed from the distinction it had achieved earlier in the century, under the régime of Leroy, and had come to consist mainly of ringing the changes on one or two basic styles in innumerable small ways. Worth’s genius for original design and his flair for elegance led to spectacular success. He became the favourite dressmaker of the Empress Eugénie, who was the fashion leader of Europe during the Second Empire. Soon nearly every crowned head and other ‘royals’ from all over Europe, together with women of fashion from a host of other countries, especially and in growing numbers, from America, were making a visit to his handsome and luxurious showrooms a regular routine part of every visit to Paris. Improbably, even Queen Victoria was at times dressed by Worth, though she could well have been unaware of it. Jean Paul Worth, son of Charles Frederick, and, with his brother Gaston, successor to the business, said: ‘We made many a dress to her measurements, and sold it through English dressmakers.’ That was a recognised procedure in fashion at the time.

In 1864 Worth was employing over 1000 workers and as he continued to advance it was evident that ‘an immense luxury industry had been created for which Worth was largely responsible’. It was, of course, at this time an industry only in size – the sewing machine, which had become a practical reality in 1851, had no significant effect on his craftsman’s methods and mass production was as remote as the moon from what he was doing. By virtue of the scale of Worth’s activities, however, fashion was being given a new status and dimension and was being extended in a way that was to lead logically to interpretation in commercial rather than individual terms.

The great step by which Worth set on foot the revolution in fashion was his production of models not only for private customers, as in the past, but also for sale to top dressmakers and eventually, as the making of fashion developed, to manufacturers and big stores in France, England and, above all, in America, for copying purposes. Towards the end of his long career this side of his business became the dominating one. By the later years of the nineteenth century he had laid the foundations of the new concept of fashion as big business which was to develop in the twentieth century and had established Paris Couture as its fountainhead.

Worth also introduced mannequins, many of them English, to show his clothes to private clients, shop buyers and dressmaker copyists, instead of using the ‘dummies’ hitherto customary for this purpose. This was a major step in fashion presentation. There was, however, nothing like the later mannequin parade, and these early model girls are reported as having invariably worn tight-fitting, high-necked, long-sleeved black garments under the fashions they displayed. Much later Balmain, in My Years and Seasons, stated that at the beginning of this century mannequins showing evening dresses still wore cover-up garments of this kind. It was not seemly for them to be gowned like the aristocrats of fashion.

All in all, Worth was the first great fashion tycoon. He lived up to his name ‘The King of Fashion’ and the Second Empire was rightly called the Age of Worth. He lived royally, entertained lavishly, travelled in a private wagon-salon and presented his clothes (the first ever to be produced on a scale that merited the description ‘collection’) in a drawing-room atmosphere of great elegance. He lived until 1895, active to the last, and left his two sons to carry the name of Worth with undimmed glory well into the twentieth century. The impetus of his achievements in fashion not only contributed to its contemporary brilliance but also, as other new factors began to operate, helped to carry it, during the next century, into the life of every woman, whatever her age, class or way of life. ‘The boy from Lincolnshire beat the French in their own acknowledged sphere,’ said the Times in a leading article when he died on March 10, 1895. ‘He set the taste and ordained the fashion of Paris and from Paris extended his undisputed sway all over the civilised and a good deal of the uncivilised world. He knew how to dress woman as nobody else knew how to dress her.’

16 Fashions at a Paris Exhibition, 1907

By the turn of the century Paris fashion, largely due to Worth, had attained a structure recognisably like that of haute couture in more recent years. A considerable number of fashion houses had come into being and were flourishing in a Paris which was drawing more and more visitors from all over Europe, Britain and America. In addition to the wealthy and leisured, the great middle classes were now enjoying the pleasures of ‘gay Paree’ and among its entertainments were its splendid exhibitions. The great one held in 1900 was a landmark in fashion, because it included a section in which a series of tableaux showed the latest elegancies of fashion. All the leading dressmakers of the day took part – Doucet, Paquin, the Callot Soeurs, Redfern and Worth among them. Mme. Paquin, who was the President of the Fashion Section and who had opened her House in 1891, was the first successful woman in haute couture. She numbered Royalty among her customers and by the beginning of this century had set up a branch in London, where Redfern had started his career and where Worth was already established. By 1902 she was advertising her establishment at 39, Dover Street, Mayfair and announcing ‘each creation original and produced in Paris and London simultaneously’. Later she also opened branches in Buenos Aires and Madrid. Her contribution to the 1900 Exhibition consisted of a wax figure of her supremely elegant self wearing a beautiful dress. Worth showed a series of fashion tableaux, with figures wearing appropriate ensembles for various occasions. This venture was another indication of the growing interest in fashion among the public and so successful was it that police had to be called in to control the crowds.

Another important sign of the widening attention being given to top fashion and a new means of spreading it lay in its close connection with the Stage at the close of the nineteenth and the early part of the present century. The Stage began to take the place of Society as a fashion-setter. ‘In the nineteen hundreds,’ says Barbara Worsley-Gough in Fashions in London, ‘the stage reached its fashionable apotheosis. It was the focus of social interest, and its leaders had usurped the leadership of fashion which had been held by the great ladies. Photographs of actresses vied with photographs of the professional beauties in public esteem. Soon they ousted them completely. Fashions in clothes, in hairdressing, even in mannerisms, were set from the stage.’ As far more people attended plays than could ever see the Society beauties and study their clothes fashion was widely disseminated. ‘The first night of a play had become a fashionable function which both the frivolous and the serious sets attended. Actors and actresses were welcomed, sought after, cultivated, envied. Royalty approved of them. In fact almost everyone in Society did.’ To round off the picture, some of the professional beauties, like Lily Langtry and Mrs. Wheeler, became professional actresses.

Leading actresses were dressed with great magnificence by top couturiers, both on and off the stage, and immense public interest was taken in what they wore, especially in the drawing room comedies and romantic plays, which were so popular at this time. But, in addition, historical plays were presented in contemporary fashionable dress, even if the settings were as remote as ancient Rome. So important was stage costume of this kind considered to be that leading newspapers and magazines published detailed reports of the clothes worn on the stage along with their criticisms of the play itself. Eleanora Duse’s biographer records that she was dressed by Worth for 30 years, until her death in 1924. Sarah Bernhardt, though she created some of her own spectacular fashions herself, also went to Worth. Réjane was dressed by Doucet.

Among the most elegant and fashionable actresses of the early nineteen-hundreds was the American Maxine Elliott, a leading figure on the stage in the U.S.A., Britain and Europe and a star noted not only for her beauty and glamour but also for her supreme fashion-sense. Some of her sumptuous stage toilettes are described in her biography, written by her niece, Diana Forbes-Robertson. In September 1903, starring in a fashionable comedy, ‘she would first step upon the stage in a creation of heliotrope chiffon velvet with a chemisette and hanging oversleeves of lace, topped by a large black hat with sweeping ostrich feathers, a black fox stole round her shoulders, and a black fox muff carried lightly upon one forearm. A white satin ball dress draped in classic style with silver trimmings would be the high point in the second act. The clothes were fresh from Paris.’

In her dealings with Paris, however, Maxine displayed an independent attitude. In 1900, when appearing in When we were Twenty-one, she told an interviewer that ‘French dressmakers were putting sashes on everything, but it spoiled the line, so she removed them. . . . The fact that she was willing to pay the price of a thousand dollars or more for a dress gave her every right to pick it about as she saw fit.’ She also had a plan of campaign when seeking her own way with great dressmakers; ‘ You must simply move in on them with your sandwiches in a bag and sit it out till you get what you want.’ She was the most fashionable of actresses on and off the stage. In July 1905, when the play Her Own Way closed, ‘Maxine had six weeks for yachting trips, country visits, and the purchase of a new wardrobe in Paris’. Then back to New York for her new play Her Great Match in which she was ‘exquisite’ in a white lace dress and tiny tiara.

17 Actress Eva Moore in an elegant ensemble of 1902

18 Maxine Elliott, most fashionable of Edwardian actresses

19 Lily Langtry, professional beauty and fashion leader

Further evidence of how actresses were recognised as fashion leaders at this time is recorded by Ruby Miller, one of the famous Gaiety Girls, in her memoirs, Champagne for my Supper. She retails how ‘During Ascot Week, we Gaiety Girls led the fashions, trailing the lawns wearing gorgeous creations of crêpe de Chine, chiffon, or lace over petticoats of rustling silk edged with hundreds of yards of fine Valenciennes lace threaded with narrow velvet ribbon. Every stitch sewn by hand and no couturier of repute would have dreamed of copying a model gown.’ With these dresses went ‘precious hats trimmed with plumes and rich satin ribbon from Paris’ or, alternatively, small toques of fresh flowers. ‘Our gloves, shoes and stockings,’ she adds, ‘always matched’ and they carried ‘dainty parasols of ruched chiffon, feathers or lace, with the most beautiful handles of carved ivory, mother of pearl or hand-painted porcelain’. They attracted all eyes – and meant much business for the fashionable dressmakers of the day.

20 The New Woman, in her tailor-made costume, began to rival the more elaborately dressed Edwardian lady. 1900

3

Splendour and elaboration were the main features of Edwardian fashion, created for and sustained by a special kind of Edwardian lady who was the most spectacular and the most copied by the rest of womankind. But also emerging at this time were other kinds of women due in the long run to oust the Edwardian concept and swing into the future on quite different lines. Their starting point was, appropriately, the New Woman. This phenomenon appeared in the latter part of the nineteenth century, when her ‘rights’, her education, her social freedom and physical activities all began to be promoted by her own increasing efforts and to be fostered by various happenings, from the achievements of pioneer individuals in breaking down barriers to Acts of Parliament and the invention of the bicycle – the last, with all its implications, being probably the most important of all!

So far as fashion was concerned, the first outward and visible symbol of the New Woman was the tailor-made costume which, to the great credit of Britain’s part in female progress as well as to her traditional supremacy in men’s tailoring, had become, by the start of the twentieth century, the first British-born fashion to achieve international fame and domination. It had originated some time before that, and was fashionable in Britain in the eighteen-nineties. One view of its origin is that it was first devised by the British tailor Redfern, who also had a Paris house, for yachting wear at Cowes. Made by a man’s tailor from materials similar to those used for men and following a similar tradition of craftsmanship, it was the first forward-looking fashion, the first symbol of freedom to come, and in spirit, if not in design, of an equality that was to be loudly claimed in the near future. Its early versions were reminiscent of the riding habit, which was natural, as that outfit was the only one for which women had in the past sought out the tailor.