Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jonathan Ball

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

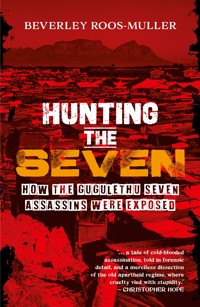

In 1986, seven young men were shot and killed by police in Gugulethu in Cape Town. The nation was told they were part of a 'terrorist' MK cell plotting an attack on a police unit. An inquest followed, then a dramatic trial in 1987 and a second inquest in 1989 that again exonerated the police. Finally, ten years later, Eugene de Kock's Vlakplaas unit was exposed at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for having planned and executed the cold-blooded killings. Yet their real agenda remained a mystery. In Hunting the Seven, Beverley Roos-Muller reveals her own decades-long connection to the case and her search for the truth of their deaths that has been shrouded in lies and mystery. Sifting through the evidence, and interviewing many of those involved, Roos-Muller reveals that it was Vlakplaas's only operation in the Western Cape and behind it lay a shocking secret.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 372

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BEVERLEY ROOS-MULLER

JONATHAN BALL PUBLISHERS

JOHANNESBURG & CAPE TOWN

For Nandi and Kieran

‘I will tell you news of your son …

Truth will come to light. Murder cannot be hid long …

In the end, truth will out.’

William Shakespeare

PEOPLE INVOLVED

THE GUGULETHU SEVEN

Christopher Piet, 25

Jabulani Godfrey Miya1, 23

Zabonke John Konile, 28

Mandla Simon Mxinwa, 23

Themba Mlifi, 30

Zola Alfred Swelani, 22

Zandisile ‘Sammi’ Mjobo, 22

THE MOTHERS

Cynthia Nomvuyo Ngewu (mother of Christopher Piet)

Eunice Thembiso Miya

Elsie Konile

Irene Mxinwa

Maggie Mbambo (mother of Themba Mlifi)

Edith Mjobo

THE CAPE POLICEMEN

Major (later Colonel) Cornelius Adolf Janse ‘Dolf’ Odendal

Lieutenant William R Liebenberg

Warrant Officer Hendrik ‘Barrie’ ‘Rambo’ Barnard

Major Stephanus Jacobus Johannes Brits

Sergeant André Grobbelaar

Captain (later Major) Johan Kleyn

Captain Leonard Knipe

Warrant Officer (later Sergeant) Geoffrey Roland McMaster

Sergeant John Martin Sterrenberg

Major Kat Coetzee

Inspector Kallie Bothma

Colonel Quintin Visser

VLAKPLAAS POLICE (PRETORIA)

Sergeant Wilhelm Riaan ‘Balletjies’ Bellingan

Constable Tikapela ‘Thapelo’ Johannes Mbelo

Askari Xola Frank ‘Jimmy’ Mbane

THE POLITICIANS

Tian van der Merwe

Helen Suzman

Louis le Grange

Adriaan Vlok

THE WITNESSES

Bowers Vumazonke, cleaner in the Dairy Belle hostel

Cecil Msutu, employee of Dairy Belle

General Sibaca, employee of Dairy Belle

THE JOURNALISTS

Chris Bateman

Tony Weaver

Tony Heard

THE LAWYERS AND FORENSIC SPECIALISTS

Jeremy Gauntlett SC KC

Gordon Rushton, Att.

Selwyn Shrock, State Prosecutor

Dr Johan van der Spuy, head of Groote Schuur trauma unit

Dr David Klatzow, forensic scientist and ballistics specialist

PROLOGUE

Seldom have seven young men been so hunted by so many.

First, assassins hunted them to their deaths.

Then, two news reporters who viewed the gruesome crime scene and its aftermath, troubled by the stark inconsistencies in the police account, hunted to establish what had actually happened.

When these reporters were charged for reporting the facts, their lawyers and forensic specialists hunted for evidence of what had really occurred on that terrible, murderous morning.

Ten years later, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was still hunting for the truth about what happened to those seven young men, pressuring the police perpetrators into disclosing their dark and hidden secrets.

I, too, hunted the Gugulethu Seven for years, after meeting some of their families in bereaved shock, witnessing the funerals and attending the hearings, trying to catch the drifting ghost of truth within the fog of denials and lies.

How does one grasp such depravity?

By hunting it.

PART ONE

THE KILLINGS

3 MARCH 1986

1

EARLY ONE MORNING …

The sky was clear and calm on that late-summer morning. The leaves on the giant bluegum trees barely fluttered as they loomed over the main intersection at the entrance of the dusty township of Gugulethu.

It was 7.20 am and the surrounding dirt streets were quiet. Those with jobs in this 62 000-strong black township had already left for work much earlier, walking through the dawning light to the railway station to reach their destinations in the affluent business centres and suburbs closer to the striking cut-out silhouette of Table Mountain, about fifteen kilometres distant – so near, yet so far.

Suddenly, there was a loud explosion, terrifying those nearby. Those still at home feared an apocalypse had arrived, so great was the volume of sound as the shots and ratta-tat-tatting streamed on. They crouched low, for experience had taught them that thin corrugated-iron walls did not stop bullets.

The terrifying salvo of shooting ceased, replaced immediately by yelling, running, engines roaring. Then more gunfire. Some single shots.

In a few minutes, it was over.

Seven bodies lay scattered across the dry ground.

The lifeless bodies were not all grouped together. Four lay close to a pair of almost identical white vans at the intersection of the NY1, the main road leading into the shabby township. The other three dead men lay at a distance: one on the dry scrubby veld in front of a facebrick hostel, two others hidden in the bushes further away – they had been running for their lives.

Baffled and traumatised onlookers gathered, but were forced back by another oddity in this bizarre scene – a very senior police presence, with many heavy vehicles in this normally underpoliced township.

Police shootings were frequent in Cape Town’s townships, but this was unprecedented: large, violent, very public.

After the police had swept away the pools of blood in the street, after the bodies had been filmed, and manhandled, and hauled away to the indifferent attentions of the state mortuary in Salt River, a stunned crowd formed while helicopter blades clattered overhead.

Later that morning, the press began to arrive. Some of them were welcomed: they were from pliable news sources sympathetic to the apartheid government, and could be relied on to quickly feed out the official version – that seven heavily armed young black men had been planning to ambush a police van arriving at a nearby police station. Others were not welcome, and were coldly eyeballed.

Tame radio stations began, later that morning, to carry a puzzling story about several communists or Russians or terrorists – this interchangeable mix was commonplace – shot dead in a fierce gun battle with the police, who had apparently foiled a dangerous urban ambush. Some families of the victims heard this sensational story but ignored it, not imagining that it was their own who were affected. They had no reason to.

Were there any witnesses? There were, despite careful precautions. The police contingent had had the advantage of an empty, morning-quiet street in Gugs, as the township is known: the timing was well chosen. But for those in power, that mattered very little: any possible witnesses were black. Crudely put, this meant they could be intimidated, threatened, even arrested under the statutes governing police action. They could be disappeared. They had no voting rights; they had no rights at all, in any meaningful sense of the word. Few in positions of influence would believe their word against any white official’s.

In any case, the apparent circumstances of this high-profile event were entirely suspicious and dangerous: what were seven heavily armed young black men doing there that morning, other than planning to ambush a police van? What a persuasive narrative this was.

2

A TROUBLED REPORTER

Chris Bateman, a 29-year-old crime reporter for the progressive morning newspaper the Cape Times, was dawdling in the police headquarters in Parade Street in the city centre around 9 am, waiting for the usual well-scrubbed daily police briefing. Then he realised that none of his other newspaper colleagues were present, nor were the familiar police faces to be seen.

He suspected immediately that he was missing out on something big.

As he was wandering around the deserted offices, the telephone rang on the desk of Lieutenant Attie Laubscher, the police public relations officer whom Bateman knew as one of the more approachable and cooperative police officers. No one else was there, so he picked it up. It was Charl Pauw, a television reporter for the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), who asked him if he had heard about the shootout in Gugulethu.

Now Bateman knew why the building was empty: there was ‘big kak in Gugulethu’.1

The journalist, who was of medium height and stocky build, with a round, fair beard and a slightly dishevelled look, quickly requested a Cape Times staff car and a photographer, Obed Zilwa, and rushed to the scene in Gugulethu. They arrived shortly before midday to find the intersection cordoned off, a large police presence and an irate though restrained crowd of local bystanders. Some policemen were throwing sandy soil on pools of blood near a large roadside bluegum tree, next to which was parked an army Casspir troop carrier. Chalk marks on the tarmac encircled bullet cartridges.

Some of Cape Town’s most senior police brass – including the retired police commissioner Brigadier Chris Swart and Brigadier M van Staden – who had rapidly arrived after the shootings, were being ushered through the dramatic scene.2 Major Dolf Odendal of the Anti-Riot squad, known and unloved in the townships, had been spotted.

At least seven armoured personnel carriers now sealed off the area of the shooting, and roadblocks had already been set up, while police vehicles could be seen stationed on the highway nearby.

None of this made sense to Bateman’s observant eye, for this township, like so many others in South Africa, was underpoliced; little attention was given to them, other than by Anti-Riot squads during unrest. Such a big show of police seniority was utterly out of the ordinary.

Bateman approached the PRO, Attie Laubscher, who brushed him off: ‘Chris, ek kan nie met jou praat nie! Jy moet Pretoria bel.’ (Chris, I can’t speak to you! You must phone Pretoria.)

This was an oddly guarded statement, Bateman thought; why would Pretoria headquarters have to be contacted about a local shooting in the Cape? He tried to cajole Laubscher, who remained adamant he could not say anything.

Despite the PRO’s reluctance, some reporters who were trusted by the police were indeed being briefed. Those were the first reports to hit the news, fed to the government-controlled SABC radio newscasts.

Bateman realised he was getting nowhere; he needed to find another way into this story. He focused on the nearest and most prominent building in the immediate area, the two-storey Dairy Belle hostel. Built to accommodate that company’s workers, the hostel usefully had windows looking directly onto both the intersecting streets – the NY1 and NY1113 – where the shootings had happened.

Fortuitously, Bateman had grown up at a trading station in KwaZulu-Natal where many of his childhood friends were Zulu, so he was a fluent speaker; this meant he could also understand Xhosa, a closely related language more commonly used in the Cape, particularly in Gugulethu. This skill would prove vital to the breaking story and its eventual unravelling.

Slipping in through the back door of the hostel, he spoke first to Bowers Vumazonke, a 28-year-old cleaner, who readily told him of a shootout by the police aimed at a small group of black men. He had heard a big bang, he told Bateman, and, looking out of the window, had seen a man lying under the big tree at the intersection. He had run out onto the street and then saw that same man being shot in the head by a policeman. There had been two more bodies lying nearby.4

Bateman then went upstairs and spoke to 60-year-old Cecil Msutu, who had been employed by Dairy Belle for 23 years. He described having first heard a loud explosive noise (later said to have been a hand grenade going off), followed by fierce gunfire. One combatant had collapsed near a large bluegum tree, and a policeman had walked up to him and ‘finished him off’, shooting him in the head. Another man had emerged from the bushes – the non-indigenous wattle and Port Jackson acacias that had swallowed up much of the Cape Flats – with his hands above his head. A policeman had approached him, kneed him, and turned to another policeman for some kind of confirmation; Msutu had clearly heard a white officer shout, ‘Skiet hom!’ (Shoot him!) and had seen the policeman turn back and fire two shots at virtual point-blank range at the victim’s head. Msutu showed Bateman a bullet hole in the hostel window: at the height of the gun fight, this witness had spent some time ducking below the windowsill.

His third witness, 39-year-old hostel dweller General Sibaca, told Bateman that he had seen a man near the bushes on the far side of the road. A policeman had walked up to him, confronted him, kneed and kicked him; then he had turned back and shot him at virtual point-blank range.5

Bateman said later, ‘I remember thinking it was too much of a coincidence: the witnesses being at different places, hardly knowing each other, yet their stories being so alike. And I remember saying to them [in Xhosa], “This is a serious allegation. You realise what you are saying? What you are saying has great implications.” But they were adamant that, in fact, that is what had happened.’6

Bateman jotted down this information in his small green-covered notebook, and quickly sketched a plan of the hostel, marking where the witnesses had been, as well as the bullet holes inside. Armed with so much incendiary information, he concluded that if his instincts were right, he was sitting on an explosive news story that needed to be handled very gingerly.

Chris Bateman’s swift drawing in his reporter’s notebook of the Dairy Belle hostel at the scene of the killings: the top strip marked ‘Rd’ (road) is the NY1, the main road leading directly into Gugulethu.

On news-desk duty that day was Tony Weaver, an experienced reporter who had faced plenty of dangerous conditions. When Chris Bateman called him and said, ‘This thing stinks’, Weaver was perfectly positioned to understand. ‘His reporting that day was extraordinary,’ he says of Bateman, who is a modest man, and wouldn’t say it of himself.7

Weaver admits that up until that time he wasn’t completely sure of Bateman. Neither of them had worked at the prestigious long-running newspaper for long: Bateman had joined in 1983, as a specialist crime reporter from the smaller Natal Witness, while Weaver had returned from a difficult stint in war-torn Namibia just a few months before. Politically connected journalists like Weaver were always watchful of crime reporters, who were inclined to become too close to the police.8 But it quickly became clear to Weaver that Bateman was of a different cut.

At 30, Weaver was tall, dark and rangy, with a self-possessed air – a man who could handle himself. Their personalities and appearances may have been quite dissimilar, but Bateman and Weaver were devoted to the same goals: to pursue the story fearlessly and accurately, and not to be intimidated into pulling back, as so many of their more prudent-minded colleagues had done to appease the authorities, and avoid potential charges about how they covered police action. These two reporters knew that their coverage differing from the official version would mean they would both come under serious pressure in the coming months – and that pressure certainly came, carrying a heavy clout.

Bateman made his way back to the office, usefully located in the city centre just a block away from St George’s Cathedral. Weaver, meanwhile, began to field calls from overseas news organisations, most insistently the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), which had picked up the early police version put out by compliant media sources: that a brave band of policemen had foiled an ambush on a van ferrying policemen into Gugulethu. All seven of the terrorists had been quickly killed during a very dangerous gun battle, yet all the police had been spared. This was, the story went, a triumph of intelligence work and anti-terrorist training, highlighting the police capacity to secure the country.

Still: all seven suspects swiftly killed, stone dead, in a chaotic shootout on wide-open ground, with no injuries to others at all? This all seemed more than just lucky – and in a country riven by apartheid violence, very few who were politically acute were inclined to believe such self-serving miracles.

Weaver was a main point of contact for a host of major overseas news sources, including TheTimes and TheGuardian in the United Kingdom (UK), TheNew York Times and TheWashington Post; he had wide experience in international news reporting, having also been a correspondent for The National, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC’s) flagship news programme. For now, though, he gave out little information, confirming only what was already available – he felt protective of the Cape Times scoop under the byline of Bateman, who had done the first critical legwork.

They both knew, however, that time was of the essence. The moment the authorities knew about Bateman’s very different version, which challenged the kernel of their own, it would likely be banned under the provisions of the weighty and censorious Police Act.9 Far too many important stories had already been extinguished from public view using this method.

3

THE LAUGHING POLICEMEN

Reluctant to hang around the newspaper office waiting for Pretoria police headquarters to deliver some useful material about the dramatic story, Chris Bateman decided to follow up a lead: he had word that some of the policemen who had taken part in that morning’s shootings were ‘available’.

He and photographer Ivor Markman drove to the headquarters of the Murder and Robbery squad in Bishop Lavis, out on the Cape Flats, where they were regaled by some of the excited police who had been involved in the shootings.

Captain Johan Kleyn, who had thick brown hair and a moustache, and was casually dressed in a spotless light-coloured shirt with short sleeves, had been at the very heart of the gun battle. In excellent shape after his ordeal, he proudly showed Bateman a small array of ‘guerrilla weaponry’ spread across a tabletop, behind which he and some of his colleagues posed for the cameras: a few pieces of grenade, an AK-47 assault rifle, a Tokarev pistol and two revolvers (a .38 and a .45). There were also bullets, and a pin Kleyn claimed to have retrieved from an exploded grenade.1 When asked whether this was the entire weaponry of the ‘terrorists’ collected from the scene, Kleyn replied ‘Yes’ clearly, and was recorded doing so.

Johan Kleyn, Kat Coetzee and Kallie Bothma with weaponry allegedly used by the Seven. Photograph: Ivor Markman.

This act of hubris – or perhaps naivety – in the post-event flush of adrenaline was one of several early mistakes, for Markman’s photographs had now recorded for posterity this quite paltry haul. It turned out to be completely at odds with later, police-issued photographs displaying a much larger, more menacing collection of weaponry, including AK-47s wrapped in a distinctive traditional blanket recovered from the scene.

The animated policemen gave their version of events, recalled Bateman, drily. ‘They said they had received a tipoff that a police van, carrying change-over shift staff to the Gugulethu police station, would be attacked early that morning, and that they had set a counter-ambush. I deliberately avoided confronting them with my eyewitness versions, as it would have immediately compromised my informants.’2

While photographing this evidence, Markman was struck by how self-congratulatory these police officers seemed: ‘It was so chilling to see them laughing; they were so proud of what they had just done … it was just one big joke.’3

This visit to Bishop Lavis resulted in more questions for Bateman than answers. The overly propagandistic response by the police, with the array of so-called Russian weapons displayed, and their bragging comments about having bagged ‘terrorists’, gave him pause. While he knew there were some AK-47s in the townships, those bits of Russian grenade and the Tokarev pistol that the police had displayed, as well as the total lack of any similarly large ‘terrorist’ incidents in the Cape, added to his suspicions.

Bateman voiced his concern by asking Captain Jan Calitz, the senior Western Cape police PRO widely believed to be a functionary of the securocrats – those shadowy figures in the state security cluster who controlled the police and the military, including politicians, generals and high-ranking civil servants – why Murder and Robbery detectives were involved if it was an ‘anti-terrorist’ operation. His was a reasonable query, given that such an anti-terrorism unit existed for this express purpose. Calitz’s aggressive, snapped response was curious: why did Bateman think that these men could not combat terrorism? Calitz then admonished the surprised journalist for not supporting the police actions: ‘Kry jouself ’n ruggraat, man!’ (Grow a backbone, man!)4

At the Cape Times editorial conference that evening, the editor, Tony Heard, subjected Bateman and Weaver to a tight interrogation, repeatedly questioning the account they had put before him. Shortish, and youthful-looking in his late 40s, Heard had been one of the youngest editors to lead a major – and, at that time, prestigious – South African newspaper when he was appointed to the Cape Times editorship fifteen years earlier, a paper he had cut his teeth on as a junior reporter. His father, the esteemed veteran journalist George Heard,5 had once worked there too.

Bateman was convinced of the accuracy of his hostel witnesses, and after due consideration, Heard did what good editors should do, though often enough do not: he decided to trust his reporters and run with their story. This was by no means a decision taken lightly. Heard, a sturdy editor who refused to pander to government pressure, was, however, used to making controversial decisions that his publishers, the owners and management of his newspaper, did not like. They had labelled him – not without reason – as ‘left inclined’. But his personal leadership and principles gave his reporters the confidence to push boundaries that other newspapers simply would not dare challenge.

Having decided to run Bateman’s story, the paper now had to work out a practical way around the restrictive laws involved.

As was required under media regulations, Bateman included the official police account of the ‘attempted ambush’ in his news reports for the next morning. This claim was that acting on a tipoff, the police had intercepted the Gugulethu Seven6 around 7.20 am, when a detective – Captain Kleyn – approached the group on foot with his sidearm drawn, after which one of the suspects threw a hand grenade which had a four-and-a-half-second delay (an unusually fine detail), enabling an athletic feat in which Kleyn dived for cover, firing, while the police car from which he had emerged was able to drive clear. One police source told Bateman that the detectives who had initiated the contact were incredibly lucky to have escaped with their lives.7

No matter how cynical the Cape Times journalists were about this police press release, they had to run it in order to observe the strict, and enforced, regulations. They prepared to put the paper to bed for the next morning’s early deliveries.

That same evening of 3 March, the state-controlled SABC television channel (no other news channel existed) led with this dramatic breaking-news story in its 6 pm broadcast. Directly after the theme music had played, the urbane news anchor Michael de Morgan opened with, ‘Police have killed seven terrorists in an early-morning gun battle in Cape Town’s Gugulethu township. Shooting started after police foiled ANC8 plans to ambush a patrol.’ The grim event was graphically covered, despite the usual sensitivity about showing dead bodies during family viewing hours. Dramatic close-up visuals included an unnamed black man lying dead, on his back, his face clearly visible, a hand grenade cradled between his abdomen and his arm.

At this stage, none of the Seven’s families had been informed of their deaths.

4

GRIEF AT THE DOOR

It was still dark when Eunice Thembiso Miya rose for work that summer morning. She needed a very early start to hold down the two jobs that supported her family.

Before she left for the Gugulethu railway station to catch the 4.45 am train, she washed and dressed, then, in her small, sparse kitchen, she prepared a simple breakfast of bread and cold water for her son, Jabulani Miya, aged 23, one of her five children. He had wandered into her shack from his own, which was in the same yard, where hand-scrubbed washing hung out to dry in the blustery summer breezes.

Surprised to find him up so early, she had asked him what he planned to do that day. Jabu, a father of three youngsters, answered that he was going to look for a job; he asked if she could give him R2 for the taxi.

Eunice had only R5, just enough to buy her weekly train ticket on that Monday morning. The weekly ticket offered cheaper transport than a daily minibus taxi, which cost R1,40 for a round trip, so it was an essential saving for her, even though the taxis were more convenient. She pointed this out to her son. Nevertheless, her mother’s heart won out, for she hoped he would find employment, so she split her R5 with him.

‘Thank you, Mama,’ he responded.

He said he would walk with her to the station, and they set off together, but a short distance on, she told him to go back home. He nodded, turned and left, and she walked on to catch her train.1

Later that morning, while she was routinely cleaning during her second job of the day, Eunice was approached by the woman she worked for. It was about 10.30 am. Her employer called her: ‘Eunice!’

‘Madam?’ she replied, turning around.

The woman told her of a radio newscast – that there were ‘Russians’ in Gugulethu who had been killed – and questioned her about whether she had a son involved in politics.

‘No,’ said Eunice, in some surprise. ‘I don’t have any son who is involved in politics.’

She continued working and thought no more about it.

Young people enjoying a sunny beach outing. Jabulani Miya is in the centre, wearing a striped T-shirt and a big smile, a large boombox in his hands. Photograph: TRC archive.

After her shift finished at around 2 pm, Eunice did some shopping, then caught the train home, arriving after 5 pm – she had been away for a long, twelve-hour workday.

Exhausted, she sat down next to her daughter, who switched on the TV news. They heard the theme music, and immediately following it watched a story of the killing of seven terrorists ‘from Russia’ (so she remembered it). ‘One of them was shown on TV who had a gun on his chest. He was facing upwards. And now we could see another one, and a second, only to find that it’s my son, Jabulani. I said no, it can’t be him, I just saw him this morning, it can’t be him! I can still remember what he wore this morning. He had navy pants and a green jacket and a warm woollen hat.’

She argued, in shock, with her daughter, that it could not be so. ‘I prayed: oh, no Lord! I wish this news can just rewind. Why is it him?’2

No policeman had come to give her the news of her son’s death. She had suspected nothing until she saw his dead body with her own eyes, on TV.

Nomvuyo Cynthia Ngewu was settled in at home that afternoon in Gugulethu, in the small brick house she shared with her husband and four children. She had originally come from Alice in the Eastern Cape, where her son, 25-year-old Christopher Piet, had been born. He was an attractive, stylish young man with short dreadlocks, who, according to his family, lived for his music. He had a young daughter, Lucanda.

Piet had been working at a bakery, and at other piecemeal jobs from time to time. He was also, his mother said, very helpful to her, fixing things and helping out around the house.3

Although he kept himself informed about politics, he had never been in trouble with the police, detained or in jail. His mother was certain that he had never belonged to the ANC.

Suddenly, four or five youths appeared at her door. They asked Cynthia where her son was, and she answered that she did not know. She told them that he had taken some money from her earlier, telling her that he was going to work.

They replied that some men had been shot, and suggested she go to the police station to check it out. In that fraught political climate, they would not have been foolish enough make enquiries themselves about who was dead, and so risk being detained – or worse.

‘I went to the police station. I asked the police about the shot people. I just [wanted] to find out about my child. They said they don’t know, they’ll check the books, they don’t have the list of the shot children4, I must go to the mortuary at Salt River. I immediately went. There, I tried to tell them I am looking for my child, because I heard there were shot children. They asked me if I can be able to identify him. I told them, yes, I can.’

Christopher Piet. This image is displayed at the Gugulethu Seven Memorial.

She saw a trolley with a body on it. It was her son, Christopher. She saw that he had a wound on his head, and there was blood coming from his ears.

After this grim identification process, she was asked to write down his personal details, which she struggled to do.

‘I went back to my house, I told everybody that I identified my son, he is also one of the Seven. I told everybody, let’s watch all this on TV because we don’t really know what happened, maybe they will have it on TV. While we were still watching the news, I saw my child. I actually saw them dragging him. There was a rope around his waist. They were dragging him. I said switch off the TV, I saw what I wanted to see, just switch it off.’5

Cynthia Ngewu would never forget the shock of seeing her son’s body being dragged ‘like a dog’.6

Long-time widow Elsie Konile, aged 56, was a traditional Transkei woman; unlike the other mothers, she did not wear western-style clothing and spoke no English or Afrikaans. Her three grown daughters were already married. Her son, 28-year-old Zabonke, wasn’t married, but had a tiny daughter at the crawling stage.

Zabonke, who was his mother’s sole financial support, had worked for a timber company building shacks, and occasionally spent time over the weekends helping women in the adjacent KTC squatter community to build their shacks. He was a close friend of Christopher Piet.

A man known to Elsie simply as ‘Peza’ arrived at her home and asked for Zabonke. She replied that she thought he was in ‘Cape Town’ – for township dwellers were Capetonians in name only: although Table Mountain was within visual reach of Gugulethu, it was part of the world that had reduced black South Africans to ‘second-class citizens in their own country’.7

Then Peza told her he had been sent by the comrades to fetch her, for it was thought that her son may have been among those shot.

‘I didn’t even know what Cape Town was, what a town looked like. When he took my hand, my whole body just shivered.’

Peza took her through unfamiliar streets to a hospital, where he spoke for a long time in English, which she did not understand. She was given tablets and an injection, and left alone for a while.

When Peza returned, he told her that her son had been killed: that there were seven dead, and that her son and another man had held their hands up, asking for mercy.

She was then taken to the mortuary. When the door opened, it released a rush of deathly chill into the warm outer room; at this point, Elsie lost consciousness.

After being treated, she was asked if she still wanted to see Zabonke.

She replied that she did. ‘So I went. I could see that this was my child, but he was filthy, absolutely filthy. All swollen up around the head.’8

One of his eyes was hanging out, and there was blood all over. She could identify only his feet; that is how she knew it was her son.

When Mandla Simon Mxinwa did not come home on that Monday evening, his mother, Irene Mxinwa, wasn’t too concerned. He was young – about to turn 24 – and she was used to him staying out overnight.

She had heard news of seven men being shot that morning, but had thought little more of it – they did not live very close to the area of the killings.

But as one day bled into the next, she began to worry. Simon had been depressed about recent, serious illness in the home – first his father, and then a sibling’s child, who now lay dying in hospital.

He was not a naughty son, she recalled, but they lived in dangerous times. ‘There were mischievous things that Mr Barnard, a policeman, use to do to the children,’ she said. ‘He used to insult them.’9

Warrant Officer Hendrik ‘Barrie’ Barnard was a notorious security policeman who prowled the townships dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, cradling a shotgun in his arms, with two pistols on his hips and his chest crisscrossed with bandoliers of ammunition. His nickname, which he carried with a swagger, was ‘Rambo of the Townships’, and those communities dreaded him, with very good reason. As Tony Weaver put it about the men who policed the townships: ‘They were the law. They could do what they wanted.’10

The townships feared Barnard’s uncanny ability to escape dangerous situations, and spoke of him as ‘the cop that couldn’t be killed’, some suggesting that he used special muti(traditional medicine) to protect himself. This myth was a useful psychological aid to his dangerous mystique.11

So began this mother’s trek around the city’s hospitals, in case Simon had been admitted somewhere. Some of her relatives helped her search during this anxious time, not only in hospitals but also in prisons and elsewhere.

On the Thursday, her grandchild died. Now in mourning, she asked someone to go to the state mortuary in Salt River with Simon’s identification document, in case it was needed – she had heard chatter about his having been seen in Gugulethu around the time of the shootings.

The news, when it came, was grim. ‘My son was one of the Seven. But the worst part was to actually see this, in the newspapers and [on] the TV, where we saw our children lying on the ground, and I saw the bullet wound on the left side of his head. We had two funerals in one week, on Tuesday [for her grandchild] and on Thursday [for Simon].

‘There was not even one policeman who came to inform me about this.’12

The bereaved also included Maggie Mbambo, mother of Themba Mlifi, aged 30, and Andile Govo, nephew of Zola Swelani, aged 22, who felt he had lost a father, for his own was dead. Zola, a labourer in the Cape Town suburb of Gardens, had looked after him and his mother.

Each of the mothers found out about her son’s death in similarly traumatic ways. None of the families were informed personally by officials, who would have routinely done so in white communities, no matter the cause of death. News of these violent deaths arrived at these mothers’ doors by other means – through the media, or local contacts.

Theirs was a particularly long-lasting trauma – each mother would always remember how shocking it had been to see, suddenly, their dead son on a TV screen, or to have had to trudge to the police stations and/or mortuary to discover whether any of the bodies of the Seven were their own.

Nor were those bodies washed, or otherwise prepared, before the parents were ordered to identify them. In their grief, they had to view the naked dead men in the bloodied and torn state in which they had arrived, visible, multiple bullet holes in all of them. One mother was told there were ‘at least 25’ shots in her son.

Some of their faces were so disfigured that their bodies could be identified only by other means. This would inadvertently lead to a catastrophe for the last of the Seven families, the Mjobos, as yet mercifully oblivious to their own incoming storm.

The families were never given death certificates, either then or later, despite asking for them.

Far from receiving the usual civilities, such as the next of kin being informed, the families were then tormented by the police, some very severely, in the coming days and weeks.

Every single family rejected the accusation that their son was affiliated in any way to the ANC, or that he had been on ‘a mission’. These were not routine denials by families of activists in the face of potential charges in order to avoid guilt by association. Their bewilderment was genuine.

5

A MUCH-CONTESTED STORY

The police press release had first been run late on the afternoon of the killings, Monday 3 March, by the Cape Argus, the afternoon paper, which had squeezed it in before the final deadline under crime reporter Stephen Wrottesley’s byline: ‘7 die in City shootout’. It portrayed the dead men as ‘terrorists’, mentioning that two policemen had been slightly injured.

The quietly planned and incendiary edition of the Cape Times hit the newsstands and the stoeps of their subscribers early the next morning, Tuesday 4 March. The front page was dominated by the Gugulethu Seven story, each of the three headlines telling a vastly different story; this compromise was necessary to accommodate police regulations.

Most striking was the headline across the top of the page: ‘Man with hands in air shot – witness.’ Below that was ‘7 die in battle with police’. Both these reports were written under Chris Bateman’s byline, though the contrast between the two versions could not have been greater – the second story reflected (by law) the police version.

A third, related story, at the bottom of the page, written by Malcolm Fried, emphasised another angle: ‘Jeers as police wash away blood’ described more than 250 Gugulethu residents watching the police wash the bloodied ground, their sympathies clearly with the dead men.

Also featured on the front page was a photograph of the Gugulethu intersection where the gruesome event had occurred, and, below it, a larger photograph of the Bishop Lavis police officers, including Captain Kleyn brandishing the AK-47 allegedly used.

The compromise that had been reached in the Cape Times newsroom the previous night with editor Tony Heard was that the police version would, in accordance with the draconian media regulations, be given prime space. Therefore, on this Tuesday morning, Bateman’s central report began, ‘Seven suspected urban guerrillas were shot dead in a gun battle with police …’1 Yet he also recorded that ‘journalists were prevented by the police from entering the scene, as well as the angry crowds that had gathered’. Significantly, the word ‘terrorists’, which had been used by the police and copied by other media sources, was not included in these news stories.

Bateman’s breaking news, however, ‘Man with hands in air shot – witness’, was the headline at the top of the page. This quite different story recorded the testimony of his three hostel witnesses, who claimed that ‘at least one suspected guerrilla was shot and killed by police after attempting to give himself up’, and that ‘another suspect lying wounded on the ground was “finished off” by the police squad’.

Bateman also stated that the copy of the witnesses’ allegations had been telexed to police headquarters, and he recorded the response by police spokesman Attie Laubscher: that ‘the police denied the allegations and rejected them with the contempt they deserve’. This was an entirely routine style of denial.

The Cape Times’s Malcolm Fried had noted Bateman’s animated conversation with two of his Xhosa-speaking witnesses on the morning of the killings, and had also seen bullet holes in the hostel windowsill and fresh bullet gouges on the wall.2 His report covered the angry mood of the gathered crowd, and he described one onlooker as ‘hysterically clutching at reporters and photographers’ and saying, ‘You must tell everybody what is happening here. We want all the people to know the truth.’

But what was the truth? How to nail down that elusive concept in a divided and weaponised political system that favoured only those who held power? Penalties for challenging them were severe. News reporting was governed by the Police Act, as was public protest. The prevailing whip was the fear of harsh consequences, and no infringement was overlooked. The policemen involved, including the senior brass, had no reason to believe that their version would be openly challenged inside South Africa.

Most South African media print and electronic sources were docile, or even servile, with official radio channels used as propaganda tools, massaged by governing politicians (as had happened throughout the history of radio – Germany had been expert in this during the 1930s and 40s). The smoothly sculptured propaganda of the radio programme Current Affairs, for example, slid silkily into homes across the nation each evening, reworking stories of the day’s events that entirely reflected the policy of the government.

Disconcertingly, however, some overseas media organisations were already asking impertinent questions. Never mind: this could easily be dismissed by the Nationalist government as a leftist plot embedded in overseas countries to destroy their white-controlled nation – their familiar excuse, and one that would likely gain good traction among many local whites: that is, voters.

Had it not been for the two reporters who refused to accept the police version (and the Cape Times editor for agreeing to publish their versions), this story might never have been known. It is one of the most significant examples of fine media work in South Africa’s history, akin to a Watergate moment – although with worse consequences for these two reporters, for they were criminally charged, and Weaver had to undergo a trial.

Anyone who doubts that a free media is essential to keep democracy and truth alive need look no further than this case. Nobel Peace laureate Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu referred to Bateman and Weaver specifically, as well as their colleagues, as ‘midwives of the process to democracy … it was literally the case of people putting their lives on the line in order to be able to tell the truth’.3

As Capetonians eyed these astonishing morning headlines, Tony Weaver, freed from his stint at the news desk, hit the streets. ‘I went straight out the next day … I wanted to see if evidence had been secured. I went to Mahlubi’s funeral parlour [in Gugulethu], a big concern which handled most of the local funerals. The police had already been in contact and ordered them to bury the bodies quickly.’4

The police had moved briskly, literally trying to bury the evidence. A Mr Lane, who identified himself as from the South African Police (SAP), bullied the funeral home – if they did not bury the bodies immediately, he said, they would lose their licence and be in serious trouble, recalled Nomvuyo Hanza, who was working there at the time.5

The funeral home refused to hurry their process along because the families and activists wanted independent autopsies. They did not believe the police version, Weaver recalled.

Weaver tracked down the mother of Jabulani Miya, Eunice, to her small, poor home in Gugulethu. She was draped in a blanket, the traditional mourning garb, and was surrounded by other women in mourning with her. She told him, weeping, that ‘the first time I knew it was my son who was dead was when I saw on SABC TV, how they tied a rope to him and dragged him’.6

What Weaver most remembers is the bewilderment of all the families he spoke to. ‘Mrs Piet [Cynthia Ngewu] told me that the police had planted the weapons. They had no inkling of their sons being interested in activism; they were young men who liked reggae music and sometimes smoked a bit of dagga [marijuana]. That was it. This was a completely different story to the one we heard while reporting other police fatalities; we were used to families being proud of their sons doing their part for the Struggle.7

‘When I spoke to my township contacts, activists, they said, Tony, we don’t know who these guys [the dead men] are. We’ve never heard of them. And they always knew each other, all those who were involved – it was necessary for their survival, to know.’8

‘Knowing each other’ was a methodology carefully observed by township activists, all those involved in civics, churches, political organisations such as the United Democratic Front (UDF)9, and particularly any of those involved in paramilitary activity or training. Trust in each other was all they had. Townships had eyes; little went unnoticed. But these Seven? No one had heard of them.

On Tuesday 4 March, after that morning’s Cape Times