17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

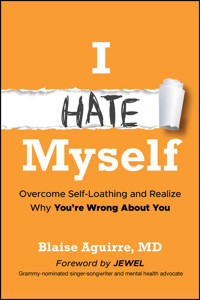

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Learn to understand the unaddressed symptom of mental health

In I Hate Myself: Overcome Self-Hatred and Realize Why You're Wrong About You, internationally known Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School Dr. Blaise Aguirre tackles the pervasive and often ignored issue of self-hatred. This book provides crucial insights into identifying and overcoming this deeply disturbing feeling, explaining why common practices of "self-care" or "self-love" often fall short in cases where self-hatred has become an integral part of a person's identity.

Dr. Aguirre shares compelling first-hand accounts from patients who have battled and conquered self-hatred, revealing the severe impact this feeling has on people from all walks of life and their loved ones. The book delves into the roots of self-hatred, associated mental health disorders, and offers practical strategies for overcoming these challenges.

In the book, you will:

- Learn to identify the origins and signs of self-hatred

- Understand the connection between self-hatred and suicidal behavior as well as to co-occurring disorders like borderline personality disorder and depression

- Discover effective strategies for transforming self-loathing into self-compassion

Perfect for those struggling with self-hatred and their loved ones, as well as mental health professionals, I Hate Myself offers a compassionate and practical approach to achieving self-acceptance. Start your journey towards healing today and embrace the self-worth you deserve.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

Introduction

Structure of the Book

Part 1: Understanding Self‐Hatred

Chapter 1: What Is Self‐Hatred?

Not Just Messing Up

Related Concepts

Chapter 2: Why Is Overcoming Self‐Hatred So Critical?

A) The Suffering It Causes: Lived Experience

B) The Risk of Suicide

Chapter 3: Common Signs of Self‐Hatred

Questions About Your Experience

Chain Analysis: A Tool for Recognizing the Factors That Cause Problematic Behavior

Chapter 4: The Lived Experience

Impact on Thoughts

Thoughts Lead to Emotions Lead to Behaviors

Impact on Relationships

Impact on Hope

Impact on an Overall Sense of Self

Chapter 5: What Is the Self That You Are Hating?

Meandering

What Do Stories Have to Do with the Self?

Fighting Against Yourself

Are You Bacteria?

Part 2: Roots of Self‐Hatred

Chapter 6: Where Does Self‐Hatred Come From?

How Far Back Do You Remember Self‐Loathing?

How Does Self‐Hatred Develop?

One Patient's Reflection on How Her Self‐Hatred Developed

Chapter 7: Could It Be Temperament or Biology?

Pain and Suicide

Part 3: Self‐Hatred in Mental Health

Chapter 8: Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Self‐Hatred

What Is BPD?

Chapter 9: Other Psychiatric Diagnoses and Self‐Hatred

Eating Disorders

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Depression

Chapter 10: Other Personality Traits and Self‐Hatred

Narcissism and Self Loathing

Perfectionism and Self‐Hatred

People Pleasing and Self‐Hatred

Bullying Behavior and Self‐Hatred

Part 4: Treatment and Overcoming Barriers to Treatment

Chapter 11: Targeting Self‐Hatred

Addressing Core Beliefs

Psychotherapy Approaches

Chapter 12: Why Is Self‐Hatred So Hard to Tackle?

Therapists Don't Ask

Avoidance

Certainty That It Can't Change

Comparisons: The Ever‐Present Trigger

Praise Does Not Work

Chapter 13: Reflections of Therapists

Chapter 14: Advice from Those with Lived Experience

Being Asked About It!

Focusing on the Concept of Future You

Practicing a Degree of Self‐Acceptance

Doing Something You Love

Noticing the Moments When the Feeling Changes

Comparing Yourself to Historically Loathed People

Identifying with the Qualities You Admire in People You Admire

Dismissing the Bullies and Tormentors of Your Past

Realizing That Self‐Hatred Was Learned

Striving for Independence

Completing a List of Pros and Cons

Focusing on the Wrong Side of Storytelling Versus the Right Side of Storytelling

Accepting the Current Moment

Practicing Core Self‐Compassion

Being Honest with Myself About the Value of the Work I Do

Talking About It in Therapy

Checking the Facts

Tackling the Fear of Getting Better

Chapter 15: Alternative Treatment Ideas

Psychedelics

Improving Your Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Part 5: Finding Hope and Technology's Limits

Chapter 16: The Dawn of Hope

I Belong

Choices

I Am Okay

Chapter 17: AI's Take on Self‐Hatred

Afterword

References

I Hate Myself

Acknowledgments and Gratitude

About the Author

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

Introduction

Structure of the Book

Begin Reading

Afterword

References

I Hate Myself

Acknowledgments and Gratitude

About the Author

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

i

ii

iii

vii

viii

ix

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

75

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

137

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

249

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

263

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

275

276

277

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

I HATE Myself

Overcome Self‐Loathing and Realize Why You’re Wrong About You

Blaise Aguirre, MD

Foreword byJEWEL

Copyright © 2025 by John Wiley & Sons. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial intelligence technologies or similar technologies.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 750‐4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our website at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data is Available:

ISBN 9781394299942 (Cloth)ISBN 9781394299966 (ePDF)ISBN 9781394299959 (ePub)

Cover Design: Jon BoylanCover Images: © Douglas Baldan/Shutterstock, © klyaksun/ShutterstockAuthor Photo: Courtesy of Blaise Aguirre

This book is dedicated to anyone who feels the daily burden of self‐hatred. You are deeply loveable. Those who love you know it, and I hope that by the time you have finished the book, you will find your path to defeating self‐hatred and recognize that you are so much more than the false narrative that told you that you weren't worth it. You ARE worth it!

Foreword

When I was 15, I was eating an orange in my hometown of Homer, Alaska. I had eaten an orange many times in my life of course, but this moment was different. My heart was heavy, and I was contemplating moving out on my own, which would entail many responsibilities such as paying rent, electricity, and food bills and of course getting several jobs to cover those costs. But those were details that I could figure out. What was really weighing on me was a problem I did not know how to solve; I was unhappy, and I knew changing where I lived would not actually solve my unhappiness.

For a long time, I thought my dad was “the bad guy.” My mom had left home, and my dad soon began drinking and became physically and verbally abusive.

In recent years, I had the realization that even when I was away from my dad, there was still a “bad guy” in my head, and that he came with me everywhere I went. Even then, I knew moving out would not change this. Today, I call it “internalizing my abuser.” I had learned how to be so cruel, so unkind, so demeaning in my own inner dialogue, that there were days I could hardly get out of bed. I could not look in a mirror. I was filled with such self‐loathing, self‐contempt, shame, and worthlessness that being conscious was mostly unbearable. Moving out would not help that. I would bring this “bad guy” with me.

So, there I was, peeling my orange, when I had an “aha!” moment. At the time I had been reading the writings of some Greek philosophers, as well as learning a bit about the impact of nature versus nurture. It got me thinking: what if my nurture was so poor, that I would never get to know my real nature? What if my trauma was so complete, so encompassing, that it might obscure my chance to know the real me? As my fingers dug into the rough and stiff orange peel, the “aha” realization struck. The peel is the orange's way of protecting itself from the outside world. The protective shell has evolved to keep the most valuable parts of the orange, the nourishing fruit and the life‐giving seeds, inside. What if I was the same? What if my painful nurture had similarly led me to develop a protective layer in order to keep my true self intact? My nurture, in part, created my personality. My environment led me to make certain assumptions about myself, ones that caused me to develop a specific type of protective defenses.

As a child of abuse and neglect, I made assumptions about my worth and value and I formed a psyche and many personality components around them. For instance, I was mistrustful. I felt worthless. I was suspicious of people. I was always waiting for the world to let me down. I lied or masked to make myself seem more likeable to people. I stole to get my needs met because I believed no one would help me meet them. All of these things formed my “peel.” But they were not “me.” They were my peel.

I stared at my half‐peeled orange, portions of the glistening fruit revealed, and I wondered: What if the fruit inside was my metaphorical nature, the real me?

Who was I on the inside? The question stunned me. I had spent my entire life confusing myself for my peel. I spent all my time wrapped up in my thoughts and opinions about myself. I was obsessed with maintaining my hardened exterior, and the assumptions I made about myself. But what if those assumptions were flawed? What if who I was wasn't the mistrustful, self‐loathing, worthless person, and the real me existed within me, sweet and nourishing? What if she was just waiting for me to turn my gaze inward to get to know her?

That day changed my life. I realized that for me to move out successfully, I had to develop strategies for what I call going down and in. My task was to get beneath my thoughts and my opinions about myself. I had to become intimate with who I was irrespective of my name, my upbringing, my job, my fame, or my family. I learned to go down and in, to fall in love with myself, slowly, and over time. I learned to be patient, compassionate, tender, and curious with, and about, myself. This was particularly hard because I had no model for doing this. No one else had ever shown me such grace, and the process was slow and progressive. To this day, I work on this. I'm still discovering and falling in love with myself. It's rewarding work. It has led to genuine happiness. I can look at my body, my life, my mistakes and feel genuine awe for the human I am.

Once you touch down into the truth of who you are, it makes you powerful. You give yourself something no one can ever take away. You know you. And there is not another one like you.

I hope that in exploring Dr. Aguirre's concepts in this book, you will begin to realize that destructive thoughts and opinions and certainties of self‐hatred are not only not true but are distracting you from experiencing the journey of a lifetime – discovering who you actually are. And who you are, I promise, is beautiful. Scars and all.

—Jewel

Grammy‐nominated singer‐songwriter, humanitarian activist, and mental health advocate

Introduction

Although I have been thinking about this topic for some time, I committed to write this book after a colleague who knew that I was very interested in the topic asked if I would do a consult with a young woman suffering with deep self‐loathing. I agreed and when I met the young person, it was clear just how intensely and enduringly she had experienced self‐hatred. I told her of my interest in the experience and that I believed that it could change. I asked her if she would be willing to work with me on changing this particular view of herself. To my surprise she said YES.

I say this because in the past, patients have told me that they are willing to work on self‐injury, or unhealthy relationships, on emotion regulation, but that self‐loathing was immutable and that they did not want to waste their time in therapy working on it.

I told the patient that there were no established protocols for working on self‐loathing and that in part we would take the current, though scant, knowledge on the topic and work together to focus on elements that worked and put aside the ones that either felt invalidating or that simply were not helpful.

Since there is limited research specific to self‐hate, I don't use an explicit treatment approach, but instead modify techniques from therapies that have proven effective in addressing related issues. I also found that by deeply listening to my patients' experiences, I gleaned valuable insights into what might work, and so I recruited some of them and asked them to collaborate with me in this endeavor. In writing this book, I have brought my patients' own voices in order to capture the totality of their interactions with the feeling of self‐hate. My hope was that their first‐hand experiences and insights would not only enrich the narrative but also provide valuable perspectives on your own journey from the certainty of self‐hatred to one where you can see that you have profound worth. What they shared exceeded all my expectations. Their worth is in their words and their reflections, and I hope that you as a reader will see that you are not alone. You are in a silent community that does not need to be silent nor need to believe the untruths you've believed. You will hear echoes of your own thoughts in their words and then use the exercises and strategies developed as extensions of their experience, as new tools on your path to overcoming self‐hatred. As I collected their experiences, I was reminded that even when a patient has largely overcome self‐hatred, their self‐loathing can still occasionally flair up.

“I nearly didn't send this to you because I felt that I could not contribute anything that would be helpful or incremental. The self‐hatred assignment was postponed by feelings of self‐hatred or at least self‐deprecating thoughts.”

This was the response to an email I had sent a patient, someone that I have known for many years, who has done so well in her life and yet who had struggled with self‐hatred for many years in her life. I was a little surprised by her response, because she seemed to be doing so much better, with a stable career, a stable group of friends, and optimism about the future, and yet self‐hatred remains. It is her experience, and those of so many others, that is the driving force behind this book.

One of the least focused‐on experiences in mental health is that of self‐loathing. In my career, I have been blessed to see so many people move from the depths of despair to enjoying the little moments of ordinary life. And yet, even for those who are working, or going to school, or are in committed relationships, self‐hatred can persist. Tragically, it is an experience that can lead to such despair, that those who are plagued by self‐loathing thoughts are at high risk for taking their life. If this is your struggle, it is essential that you know that suicide is not the answer to self‐hatred. You were not born with self‐hatred and once you realize that you can rewrite many of the false and hurtful conclusions about yourself, you can move from the contemplation of suicide to the embracing of a truer and more aspirational sense of who you are.

The Years Before

“I do not trust people who don't love themselves and yet tell me, I love you. There is an African saying which is: ‘Be careful when a naked person offers you a shirt.'”

—Maya Angelou, The Distinguished Annie Clark Tanner Lecture, 16th‐Annual Families Alive Conference, Weber State University, May 8, 1997

In the years before I thought more critically about the problem of self‐hatred, I worked with a patient, a senior in high school, who was dedicated to her recovery. She practiced new skills, she did her homework, she came to therapy every week, and slowly she moved from the ravages of emotional suffering to focusing on her academics and applying to college. She took up dance, which she had done as a child, and learned how to play the guitar. Over time she felt more in control of her life and went from seeing me twice a week to once a week and then once every two weeks. I noticed, though, that whenever she did something that she perceived as wrong or imperfect, that she would become extremely critical of herself.

“I hate myself,” she said one day.

“That's a bit harsh,” I said, “everyone makes mistakes.”

She looked at me with what I interpreted as confusion, and maybe even some scorn.

“You really don't get it. I hate myself. This is not about making mistakes. Yes, making mistakes highlights what a terrible person I am, but I hate myself now and I have always hated myself,” she said.

“But what about all the things that you are doing with your life. Your grades, your college applications, your guitar, your dance?” I persisted.

“Those things make me competent. They don't make me love myself,” she said definitively.

“I never knew this about you. Can you tell me more? What a terrible way to see yourself. How can you possibly imagine that you are so awful?”

She sat back and said: “Have a look at my life. I have ruined it. I have ruined the relationships that I care about. I probably ruin your life, too. Do you know why my parents are divorced? Me. Do you know why my boyfriend left me, and why I will never have a boyfriend again? Me. Do you see my scars? Do you know who made them? Me. Do you know why my mom is constantly worried sick? Me. Do you think she wants to spend six hours per week getting me back and forth to therapy? Do you think that she has nothing better to do with her time? It's because of me. I poison everything I touch, because I am toxic, and the world would be better off without me, such a toxic person.”

It saddened me that someone I thought so highly of, thought so poorly of herself. She insisted that she was pure loathing and that there was nothing endearing about her whatsoever.

Despite her gains, this self‐perspective did not budge, and in fact, my attempts to get her to see that she had good and love in her, increasingly felt invalidating.

“No matter how much you try to convince me otherwise, there is no good in me. It makes me think that you don't really know me, and that therapy is a waste of time. You are confusing my hard work at being more effective and less suicidal, with me caring about myself more. False, I just want to be able to make it through the day. Let's just focus on me being more effective.”

She continued to make great strides, got into her top choice of college though early action, was dancing regularly and had made some friends at school. The topic of her self‐loathing was left unaddressed, because she thought it was futile and that my bringing it up was invalidating. Also, I didn't know what to do and how to budge the debilitating and toxic symptom.

That Christmas, she came for session, and brought me a Christmas card. She had spent some weeks working on it, and the level of artistic precision, attention to color detail, and word sentiment, captured a devotion and dedication that I rarely find.

“Thank you,” I said. “You have gone to a lot of trouble to make it. It is beautiful and your words mean so much to me. You say so many nice things. Why did you make it?”

“You have helped me so much, and I appreciate it. I just wanted to show you how much it meant to me,” she said smiling.

“But I am confused, because what you write almost implies, that you care about me,” I said with intention. “I am sorry to say that I cannot accept your card. I cannot accept a lie.”

Her smile turned to shock. “What do you mean? Of course I care about you.”

“But caring is a form of love,” I persisted.

“So?” She seemed confused.

I asked, “Well how can you give me something that is not yours to give. If you steal $100 from someone, it is not yours to give to me. You can only authentically give me something that is truly yours to give. Otherwise, it is a lie. You give me a card that shows caring for me and gratitude for me, but you cannot give caring and love that you don’t have, and so you giving me those things is a lie, and I have to reject your card, but appreciate the effort.”

She was defeated and started to cry. “I can't believe it. It took me such a long time to make the card, and I did it because I care about you, and you reject it???”

“Wait,” I said, “are you saying that you do have caring inside you?”

“Yes, of course I do!”

I said, “But you have spent so many months telling me that you had no love in you, that you were a toxic person, that you poisoned everyone you met! I am beyond overjoyed by what you are telling me! Of course, if your card comes from love and caring I can accept it and joyfully so! But here is the thing, if you have love inside of you, you are not all the things that you say about yourself, and if you have love and compassion for me, it is in you, and you can start to see that. It is in you. And if it is in you, it is in you for yourself. And if you have love inside of you, how can you be so toxic? Your card would only have poisoned me if it were evil, but it comes from kindness.”

Over the next few months, she started to notice moments of acts of kindness and compassion to others and recognized that these acts came from a place of genuine caring, from deep within. And that her caring, and compassion had to be within, and that if it was within herself for others, it was within herself for herself. With time, self‐loathing eroded until all that was left was a sadness for the young girl who had not known to love herself. This was an important first for me, and a fundamentally important experience for my patient. Self‐loathing had shifted.

Unchangeable?

“Every single thing I touch becomes sick with sadness, 'cause it's all over now, all out to sea.”

—Taylor Swift, from “Bigger Than The Whole Sky”

For people with conditions like borderline personality disorder, also known as BPD, a condition that I review in a later chapter, the experience of self‐hatred does not feel as if is something that can change. It does not feel like a perspective. It has the quality of being core to who they are. When I ask those who feel this way if they have addressed it in therapy, I receive three main comments:

No, no one ever asked me about it.

Yes, I brought it up once, but they simply told me to practice self‐compassion.

No, I never thought about bringing it up because it IS who I am and although I can change many of my behaviors, I can't change who I am.

When I hear these comments, I feel profound sadness because the people making these statements are supremely talented and compassionate to others, and when I get to know them over years of therapy, I feel deep caring for them. How is it possible that someone so loveable feels so unlovable?

I want to be as clear as I can be on my perspectives on self‐hatred. It is a pathological state. It is a source of enduring suffering, and one that blinds you from seeing your true self, and all that is good in you. It can end up destroying your mind and tragically it can lead you down the path to suicidal thinking. In these pages, I hope to convince you that self‐hatred is a deception created by a mind that learned to hate itself, and that you can learn its opposite, that you are worthy.

Structure of the Book

For the purposes of this book, I use the terms self‐hatred and self‐loathing interchangeably. This is because most of my patients tell me that they are the same thing. Throughout the book, I weave narrative, dialogue, and reflections with research. Some of the ideas may feel familiar and validating, and some of it may feel too scientific. The science is important as all of therapy, all of what works, must be based in ideas and practices that can be replicated and practiced by others in different contexts. When it comes to research on self‐hatred, there is not a lot, and I think that this has to do with the fact that few patients present for therapy with self‐hatred as a primary complaint, and also that mental health professionals don't ask about it in their evaluations.

I don't think that this is a book that you necessarily need to read cover to cover. If the science feels too tedious, I have indicated the sections that you can skip without losing the thread of the helpful points.

In the book I have assigned exercises that my patients have told me were helpful to them. There are lined spaces for your answers below each exercise. I have used analogies and metaphors to try to explain what certain concepts mean. Finally, over the years, I have collected quotes about the experience of self‐loathing reflected by poets, novelists, philosophers, athletes, and musicians. I have peppered these throughout the book: They underscore that the experience is far more universal than only in people who come for therapy.

I hope you find this useful in your journey to overcoming self‐loathing and that each reader with lived experience can one day see how essential and loveable they are. Know that your value is not defined by the way you were treated, your perceived flaws, mistakes you have made, or what others say about you. You are no different from anyone else who is inherently worthy of being loved, and if you are skeptical, read on and let me, and all the contributors to this book, accompany you on a journey to seeing yourself as a person of worth and value.

Part 1Understanding Self‐Hatred

Chapter 1What Is Self‐Hatred?

“Why does shame and self‐loathing become cruelty to the innocent?”

—Anne Rice, Merrick

Self‐hatred is not a choice. You are not presented with the options of loving yourself or hating yourself and choose to hate yourself. Self‐hatred is there because you were led to believe that it is true. Your early experiences were not your fault. Any bad thing that happened to you was not because you decided that it was what you wanted. Experience after experience led you to believe that you were not worthy. You did not make self‐hatred happen, and self‐hatred does not have to be what endures. You have the power within you to define and validate your experience and then change something that you believe would never change.

I recently decided to re‐read Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë written in 1847. 1847 was a time decades before we understood the impact of trauma and invalidation on a person's sense of self. Reading the book through the lens of my current exploration, I was shocked to see how profoundly Brontë understood and articulated this impact. For instance, here is her protagonist, Jane, describing an experience at 10 years old:

Mrs. Reed soon rallied her spirits: she shook me most soundly, she boxed both my ears, and then left me without a word. Bessie supplied the hiatus by a homily of an hour's length, in which she proved beyond a doubt that I was the most wicked and abandoned child ever reared under a roof. I half believed her; for I felt indeed only bad feelings surging in my breast.”

— Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

The experience of many patients is reflected in this passage and you can have deep compassion for the 10‐year‐old Jane because you see that she did not choose to be treated in such a hurtful way. And then through years of being treated this way, it makes sense that she concludes that it must be because she is such a terrible child.

Self‐hatred is a lie that arises from experiences that you had no way of preventing. In many cases you were too little.

The self‐hatred that I tackle in this book is not some transient state. For the people with lived experience, it is a persistent, unrelenting and unyielding intense dislike of the self, and one that comes with feelings of inadequacy, guilt, self‐blame, and low self‐worth. People with self‐hatred at times see themselves as a burden that needs to be removed from the world. There is an enduring sense that “I will never be good enough.”

Not Just Messing Up

This core self‐hatred is not transient. It is not the same as, for example, someone accidently spilling a glass of red wine on a white tablecloth, or breaking a plate, or messing up on a term paper, saying: “I'm so stupid, I hate myself.” Many people have said “I hate myself” to express dissatisfaction in an outcome or an action. In this context, it typically means that they messed up; they use the expression to acknowledge to themselves and others that they are aware of messing up. “I hate myself,” uttered in these types of situations is a transient reflection of temporary upset.

50 Shades of Reaction

There are degrees of reaction when an accident happens, such as spilling red wine on a white tablecloth. For those who do not suffer from self‐hate, there may be a moment of surprise or embarrassment, followed by an apology to their host, and an offer to clean up or to pay for a new tablecloth. Then, after the wine‐spilling (or whatever incident) and apology, they continue enjoying their time without dwelling on the incident. In contrast, for those who suffer from self‐hate, the reaction is quite different. Intense feelings of shame and guilt emerge, their inner dialogue becomes harsh and critical, and they experience deep embarrassment, guilt, or even self‐disgust. They struggle to move past the incident, which weighs on their mind for the remainder of the day. While to many, it is just spilled wine; to those with self‐hate, it is a reflection of their own perceived inadequacies.

So you will see, self‐loathing I discuss in this book is a much deeper, painful, and all‐consuming problem. It is a construct that evolves over time and seems to become embedded in the very essence of the person as a core part of the self. It is as if self and self‐hatred have merged and cannot be separated, to the point that a person can never remember not hating themselves, or that the idea of challenging it seems preposterous, even a waste of time. “Self‐hatred is to me what H2 is to O in water. Water is H2O. That's me and self‐hatred,” quipped a patient.

For most people, self‐hatred and self‐loathing are the same thing, and I tend to use the term interchangeably throughout the book; however, one patient felt differently. She felt that self‐loathing was even more intense than self‐hatred and said:

It's loud in my head, all the time. So much of it is me berating my own existence. Everything I do is wrong. Nothing I do is good enough. Maybe the little failures of each day seem like nothing to other people, but when my head is already SCREAMING at me that I can't do anything right, even forgetting to put grape jelly on my daughter's PB&J instead of strawberry feels like the end of the world. How can I not mess even the little stuff up?! Sure, maybe I'm a nobody that can't figure out how to make it in this world, but AT LEAST I could put the right fucking jelly on the sandwich.

“Except I can't.”

“That's self‐loathing right there. Hatred is a walk in the park next to self‐loathing. Self‐loathing is the peak of the mountain of self‐hatred.”

“That's kinda funny and clever!” I said, “Can't you have some admiration for a mind that came up with that?”

“No, because only a mind that hates itself would come up with that. I wish that I had never had to think that” she replied solemnly.

“Well,” I reflected, “you are so much more than hydrogen and oxygen and so maybe if you can also see all the other things that make you up, your focus on this one idea might change.”

She shrugged skeptically.

I asked a patient to express the idea in a way that others might get it, and she said: “I would describe my self‐loathing to others as a pervasive feeling of being a bad person with no sense of worth or identity. And I mean ALL the time. I often feel that I am a disgusting person who is at fault for all of the problems in my life and who does not deserve care, compassion, or good things generally. And I mean ALL the time. In addition, I feel a sense of separation from self and like it does not matter if I like myself because I don't have a sense of self‐concept and often don't feel grounded in reality.”

Many people who live this way, feel that they are so flawed that they must, by virtue of these flaws, be punished for their very existence. And another point is that it endures. “People who have headaches don't know what unrelenting migraines are,” explained a patient who suffers from migraines and borderline personality disorder (BPD).

At times, self‐destructive and self‐degrading behavior follows as an attempt to self‐punish. Self‐destructive and self‐degrading behavior used as self‐punishment never works, even if there is some temporary relief. It doesn't work for various reasons; firstly, punishment is typically used when a person has done something wrong or committed a crime. What is it that you need to be punished for? There never was a crime for which you deserved punishment to begin with. If you were abused as a child, a crime was committed, but not by you. Secondly, the very “punishment” behaviors you inflict on yourself often leave you feeling even worse about yourself than when you started. And, finally, even if you had committed some crime, once you've been punished for the crime, you've served your time, and no further punishment is required. Why keep punishing yourself? Think of a person going to jail for robbing a bank; after the person is released, they don't keep going to jail for the same crime.

When a person is feeling strong self‐hatred, they not only feel that they don't deserve the love of others, but they also feel that they don't deserve anything good happening to them, and instead conclude that anything bad that happens is, to them, a manifestation of their awfulness, and a deserved punishment for being such a terrible person.

I was once working with a patient who arrived a few minutes late. She said:

“Now do you see what a terrible human being I am? I mean I wasted your time. That's what I do and that's what I am, a terrible waste of time and a terrible waste of humanity.”

“Wow, that's harsh. I was looking forward to our session,” I said. “You are always on time and so I was a little bit worried, but you're only 10 minutes late. I assume that you hit traffic, or that you woke up late, or that you were talking to your girlfriend, or that something came up at work. I never even considered that my time was being wasted. And to be honest, I quickly finished an email that I had forgotten to send. Not only am I not at all upset. It wouldn't even come into my mind. In fact, I am grateful I was able to send the email. I appreciate the extra few minutes!”

“Why are you being nice?” she asked. “I deserve to be punished for being a terrible, horrible patient. You should not be thanking me. There are no excuses for being late. I want to punish myself, but you should punish me instead. If you came over and slapped me, then it would make sense.”

I think that I started to tear up, because she said, “What's wrong?”

“It just saddens me that you hate yourself so much, that you imagine that I hate you so much that you deserve to be punished for something that happens millions of times a day, to millions of people because of the circumstances of their lives, and then that you would be surprised that in fact I have no such feelings of malice or contempt for you. I know that you are doing the best that you can.” I stopped to reflect. “For many people who hate themselves, they cannot imagine that others don't see them in the way that they see themselves. You hate yourself, and you imagine, or maybe believe, that I and others who care about you, can't possibly care about you. You worry that they are lying to you, or that they are deluded or that they cannot see how terrible you are. A psychodynamic therapist would say that you project your self‐hatred onto others and then believe that projection that they hate you. In a way, by being so certain about what they believe and how they should treat you, you rob them of an opportunity to have their own experience of you. In my case, I admire the very hard work in your efforts to overcome the mental health obstacles to you getting into college. And that admiration is true whether you believe it to be so or not. You telling me that I am wrong, is like saying that I am not allowed to have an opinion other than yours on this.”

“You see, I ‘rob’ you of your experience, I am not terrible?” she countered.

“You are a terrible knower of what I think,” I said smiling, and the tensions diffused.

Related Concepts

Colleagues have suggested that when I focus on self‐hatred as a separate entity, that what I am discussing is a set of ideas that is common in many psychiatric conditions, and that many people with other mental health conditions are discontent with themselves and with how their brains work. However, my experience tells me that self‐hate can manifest in two distinct ways: firstly, as a symptom of underlying mental health conditions AND secondly, as a standalone experience, one that lingers even when the fury of other mental health conditions has done its worst. It has me thinking: Could enduring self‐hatred, in the absence of other clinical symptoms, be its own diagnosis?

When I ask my patients with self‐loathing if self‐hatred is simply part of a mental health condition, they acknowledge that they identify with all of the ideas that we are shortly about to review, but that they are not the same. They say that self‐loathing includes many or all of the following experiences but that having any one of these related concepts would be far easier to deal with and would be far less impactful, less all‐encompassing, and less painful than self‐loathing. “If all it was, was self‐criticism, I would not want to die so badly,” was the reflection of one of my patients.

Many people with enduring self‐loathing express the following phrases: “I'm a failure,” “I can't do anything right,” “no one is ever going to like me,” “I will never be good enough,” “I'll never get better,” “I deserve to suffer because I am such a terrible person,” “I should just die,” “I deserve to be punished,” “I should never be in a relationship because I am toxic to others,” “I am to blame for all my problems and those of other people,” “everyone hates me.” Certainly, these don't help reduce the impact of self‐hatred.

Let's have a deeper look at concepts related to self‐hatred and see how they are similar and how they are different. For some readers of this book, the concepts may in fact mean the same thing as self‐hatred, and yet for others, they are ideas that don't resonate. Some of these concepts have a research base and are clinically defined, whereas other concepts are the words that those with lived experience have used.

Concepts and Experiences Related to, but Different from, Self‐Loathing

Self‐Criticism

“If you're capable of despising your own behavior, you might just love yourself.”

—Criss Jami

Self‐criticism is the tendency to engage in, and with, negative self‐evaluation leading to feelings of worthlessness, feeling that you are a failure, and feeling guilty when you don't meet expectations. Self‐criticism was originally seen as particularly relevant to the development of a specific type of depression, known as introjective depression. In clinical practice, we no longer use that term; however, it is useful to think about because historical descriptions of patients with this type of depression seem to be consistent with many of the themes in this book. Therapists would notice that some patients with introjective depression would feel deserving of being punished and so interpret therapists' comments as punishing.

When seen as a personality trait, research finds that self‐criticism has been linked to several negative consequences. In a study examining behavior differences between people who were self‐critical and those who weren't (Mongrain 1998), the research found that self‐critics experienced greater negative mood states, perceived that others were not trying to help, and made fewer requests for help. Interestingly, in their study, they found that those with and without self‐criticism did not actually differ in the amount of support they received, but rather, in how they perceived the support they got, in how they accepted it, and how frequently they asked for help.

In another study (Santor et al. 2000), in people who were self‐critical, when compared with those who were not self‐critical, the self‐criticism predicted a decrease in agreeable or kind comments toward their partners and also predicted being more blaming of their partners than those who were not self‐critical. As you can see, this is not exactly the same as self‐hatred although there may be some elements that are similar.

I asked a patient about his experience of self‐criticism, and this was his reflection: “I've always been extremely self‐critical.… So, does that mean that it is part of my personality? It's different from my self‐hatred. Do you think that it could be stemming from my other mental health struggles [like could it be part of my OCD or pathological perfectionism] or is it a separate issue? Either way, that makes self‐loathing harder to treat because self‐criticism is so deeply ingrained in my way of thinking and acting.”

Another patient said: “No. These are two different ideas. You can be criticizing of certain aspects of yourself/things you've done without despising every aspect of yourself.”

The bottom line is that while many people who hate themselves experience self‐criticism, most people who criticize themselves, do not also hate themselves.

Self‐Disgust

According to research (Overton et al. 2008), self‐disgust is a negative self‐conscious emotional pattern of thinking that organizes and interprets incoming information. Self‐disgust originates from the basic emotion of disgust and is directed toward physical self, meaning physical self‐disgust, and accompanied by statements like: “I find myself repulsive” or to some aspects of your behavior, behavioral self‐disgust, with statements like: “I often do things I find revolting.”

Research (Ypsilanti et al. 2020) shows that self‐disgust has been associated with many psychological difficulties, including social anxiety, impaired body image, disordered eating behavior, and PTSD symptoms in women with a history of sexual assault. When these researchers looked at self‐disgust in military veterans, they found that veterans with PTSD reported almost three times higher scores in self‐disgust, and significantly higher scores in loneliness, anxiety, and depression, when compared to the general population, and that it was the self‐disgust that connected the experiences of loneliness and anxiety. In this group, loneliness was defined as the subjective experience of lack of meaningful social relationships, which is common among war veterans.

I find it interesting that when I ask most of the patients who endure self‐loathing about self‐disgust, that self‐disgust does not resonate as strongly as self‐hatred. Many feel that it is a different thing. One patient who experienced both self‐loathing and self‐disgust told me: “I always hate myself, but I don't always feel self‐disgust. When I do have self‐disgust, it makes my self‐loathing worse. God forbid that I walk by a mirror, and I see my reflection. Then I am disgusted by the person looking back at me. I was shopping at the mall with a friend, and he was checking himself out every time we walked by a shop window. I looked the other way. But now that you asked the question, there is another way that self‐disgust shows up. You know like when you step in dogshit you are disgusted and want to wash it off as quickly as you can? Well, sometimes if I am at a party and I use the rest room and wash my hands and see myself, my self‐disgust shows up. When I go back into the party, I feel that I am like that dogshit, and I think: ‘My being in this room makes me think that they are probably thinking that there is something horrible and disgusting in the room, and that thing is me. My leaving would be the best thing I could do for them.’”

Another patient also recognized that there was stronger overlap with self‐disgust than with other ideas: “This is the closest (in my opinion) to self‐loathing, if not, the same. I can't think of anything to differentiate the two.”

“And I saw my reflection in a lake, and I waited for it to freeze a little bit so I could break it with my boot.”

—Sam Pink

Another patient had a different, and somewhat comical, take on self‐disgust: “Self‐disgust, for me, is PART of self‐loathing. I love the dictionary definition. Revulsion. No doubt, I am repulsed by every aspect of my being. I do think it's possible to be disgusted with yourself yet not hate or loathe yourself, though. Humans are really disgusting creatures, but their disgustingness isn't necessarily bad. Am I disgusted by the amount of farting that comes out of my husband? Absolutely. I certainly don't hate or loathe him for it. I guess it turns into hatred or loathing when it becomes a choice.”

To underscore this point, I have an acquaintance who is significantly overweight. At social outings he eats a lot of high‐calorie foods. He is an open, friendly, and well‐liked person, and he is a self‐described “bon‐vivant.” He lives a life of consumption and tells me he's the very definition of a hedonist. I once asked him if he had any regrets about his excesses. “Only when I walk by a mirror or go clothes shopping,” he answered, “when I see myself I kinda gross myself out. I'm really kinda disgusted by myself, but I don't spend too much time thinking about it. I mean that would take the pleasure out of EVERYTHING!”

It makes sense that the concepts of self‐disgust and self‐hatred are related and connected; however, research and clinical experience defines them as different constructs.

EXERCISE

Do you experience self‐disgust? Y/N

If so, how would you describe the experience to others?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________