9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

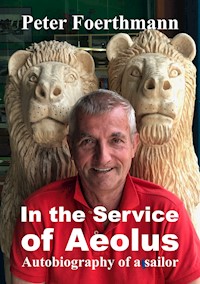

Peter Foerthmann has spent his life in the service of Aeolus, the Keeper of the Winds. He learned to harness the power of the wind first as a sailor and then as the man behind the Windpilot windvane self-steering company. The winds of fortune have by turns favoured (his serendipitous meeting with Windpilot founder John Adam, for example) and tormented (numerous legal entanglements being the most prominent example) him without ever managing to blow him entirely off course – a course that stretches to the horizon and beyond, where sailing dreams become reality (at least for those with the right transom ornament). This book presents the recollections of a self-taught original who, heedless of convention and rely-ing strictly on his own internal compass, has developed a unique understanding of social interaction among sailors, who have rewarded him in turn by spreading the word about his products effectively enough to make Windpilot the world market leader for windvane self-steering systems. Building up the company and developing a product that enables sailors the world over to enjoy long passages freed from the need to steer continuously has given Peter an all but unparalleled insight into blue-water sailing and an expertise in various related areas that he has shared in several highly regarded specialist publications. A compulsive writer, Peter takes as much pleasure in choosing his words as he does in telling his story, the story of how he swapped a boat for the idea that became his life, how he went from a tra-ditional workshop-based operation building everything by hand to what must surely be one of the world's smallest state-of-the-art industrial manufacturing companies and, most importantly of all for him, how he has managed to defend and maintain his independence both commercially and socially by sticking to his principles – fairness, respect, empathy – and learning, not without incident, to choose his friends wisely. Above all, this is the story of half a century in the windvane self-steering business, a story that – Aeolus willing – still has a long way to run.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Peter Foerthmann

IN THE SERVICEOF AEOLUS

Autobiography of a sailor

In the Service</of Aeoulus

Peter Foerthmann

Photos: Peter Foerthmann

Cartoons: Inga Beitz–Svechtarov

Copyright: © 2022 Peter Foerthmann

From German into English: Chris Sandison

Publisher: tredition GmbH, Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg

Softcover 978-3-347-72478-5

Hardcover 978-3-347-72479-2

E-Book 978-3-347-72480-8

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher and author.

Contents

PREFACE

MY LUCKY DAY

STORM, STRESS AND COMPULSION

The Scent of Freedom

Developments …

Total Freedom

The Second Career

AND NOW TO BUSINESS

THE FIVE PILLARS

Business

Sailing and living

The Breakthrough

Dead Ends and Plagues of Moths

International Boat Shows

LEARNING THE LESSONS

THE LIFE PLAN THAT WASN’T

Toxic Individuals Everywhere

In brief

Rockport, Maine: a timely time-out

London, the High Court case

Retrospective

The Flying P-Liners

21 September 1957

The Call of the Genes

Speaking of Curiosity

Life the Way I Wanted it

Pandora's Box

The Pamir Enquiry

The Carousel of Blame

Full Circle – the Social Echo Sounder

THE MARINE INDUSTRY

Life among sharks

The fight for power

From the market

Lessons learned

Working from home

HAPPINESS BY MY SIDE

So near and yet so far away

Halloween and All Saints' Day

Jackpot!

Idols and dreams

A RESPECTABLE ARMADA

Peter's fleet

From dream to reality

The moment of truth

Jet drive

The control unit

Two system types

The history of the JetStick

Decisions

From a different perspective …

MAX FOERTHMANN – YACHTSMAN, MUTT

LIFE LESSONS

Alone or, preferably, not

Reflection and resilience

Harmony à deux

Caution: word games ahead

No panic on the Titanic

Word of mouth makes the world go round

Beware retired visitors

Boat show parties – social collisions

Peter – word wrangler

What, where, how

I admit it

The blue touchpaper

The call of the genes

In my own world

PETER UNPLUGGED

Life in the fast lane

Going toe-to-toe

First name terms

How formal? How informal?

No good going it alone

Trapped by kind words

Formality and respect

Sailors don't do surnames

Sailors – a charming family

Respect is the magic word

Encroachment and subordination

The Sailing Bug

The sailor as king customer

The Lion

The Scotsman

Respect oils the wheels of life

Other business concepts

My way

Encroachment

BIG BOY'S TOYS

THE WRITTEN WORD ENDURES

EPILOGUE

How I see it

Dialogue or diktat?

The chink in the armour

Of hormones and such

My programming error

A position of relative comfort

Preface

A book about an entire life? That could easily go wrong. How is an author to decided what to include and what – if anything – to omit? Every recollection adds more colour to the tale and therefore has a claim to be told, but the reader needs a story to enjoy, not a faithful retelling of an entire existence. Somewhere there is a tipping point beyond which more information dilutes rather than enhances the experience, beyond which tedium replaces entertainment.

Short cuts can be a handy recourse here. Throughout my life I have always been a fan of seeking out my own, faster way to progress. Doing things my own way has allowed me to set the pace of my life, to study, learn and acquire necessary skills at the rate that suits me and advance my cause and expertise with a rapidity that can sometimes leave feathers ruffled.

I am motivated in many ways by the urge to please, but this impatience of mine has a tendency to undermine my efforts in this area. I have never really managed to keep everyone happy though and have been reminded, from time to time, that it is in ceasing to try to do so that I come nearer to independence and freedom. This realisation has helped me enormously: striking an effective balance in life is much easier with a clean, fair hull and no unnecessary ballast.

This book addresses what I consider to be the central pillars of my life; structures that have helped me keep my head above water in a hostile shark tank and – eventually – learn to tell the difference between a friendly smile and a hungry leer.

I have had the support of some remarkable individuals, to whom I owe a debt of thanks beyond measure. When I say that I could never have written this book without my mother, I do not just mean in the obvious sense. I have realised over time that my love of writing comes very much from her – indeed is a continuation of her own urge to commit the things that matter to the written word. Writing, for me, is an elegant way to pan the gold flakes from life‘s events and milestones and keep myself on course with a smile.

It comes to me naturally to do things this way, to live, reflect, process and move on, for that way every day brings the promise of a new adventure. I thrive on the freedom that living like this brings, but I also acknowledge that such an approach requires time and – most important of all – can only work in a harmonious relationship. I was born to share, made for a team of two, and it is flying side-by-side on the magic carpet – the dream of dreams – that I am fulfilled and energised. A problem shared is a problem more than halved while joy and pleasure shared is more than doubled: can there be anything more remarkable?

21 May 2022Peter Foerthmann

My Lucky Day

I would like to say I emerged into this world on an elegant schooner clutching a screwdriver in one hand and a pen in the other, but actually I arrived wet and howling just like everyone else – in my case at Hamburg’s Jerusalem Hospital in May 1947. I was picked up, briefly inspected and then snuggled up at my mother‘s side to sleep off the shock.

My early years were fairly typical too: plenty of do this, do that – and definitely don’t do that. Resistance was futile – believe me I tried and believe me it hurt. The world seethed with temptation, overflowed with restrictive rules. Some of them even made sense, usually once I found out what happened when I ignored them.

A child perceives no deeper meaning in rules and consequences, they are both just obstacles to be evaded or, in the worst-case scenario, weathered as quickly as possible before returning to business as usual. I was no different and would never, ever have suspected that, decades later, I would actually come to appreciate and be grateful for my mother’s firm and consistent approach to child rearing. I made the most of what freedom I was allowed and I enjoyed myself: life was simple and the world full of opportunities.

My first love proved long and enduring – and also something to endure, especially when I had to cycle around with her on my back. Hauling my violin around exhausted me and together we were a source of exasperation for both my mother and my music teacher. My instrument and my wheels, my muse and limousine, kept me from becoming involved with people, from criticising them and even from defending myself. That would have made me easy pickings for the bullies except that I wasn‘t really bothered, which didn‘t suit their agenda at all.

No boy can avoid confrontation for ever of course, but I managed to limit my serious dustups to one with my brother – who still bears the scars of my attack (at least that’s the way his wife puts it) – and some other kid who never amounted to anything as far as I know (unless, that is, you consider being a senior international judge at the UN tribunal in The Hague an achievement).

Water enjoyed a place close to my heart from my earliest years – provided I wasn’t expected to wash in it. I understood cleanliness had its place but it required a commitment of time I could not afford to make. Perhaps also I was discouraged from washing overmuch by the fact that it fell to me to empty the zinc tub down the drain afterwards (as you can see I also understood the importance of having a halfway decent excuse ready to go when I needed it too).

I soon claimed the Hamburg harbour for my own and would hurtle down there on my bike whenever possible. It was a short journey with the fear of missing something exciting on the ever-colourful waterfront driving me forwards. My personal soundtrack for those years came, logically, from Austrian singer Freddy Quinn, whose tales of the sea struck a chord in my young mind. I was transfixed, transfigured, enchanted, my mind away over the far horizon in moments.

My mother, who played the harpsichord and piano and preferred to spend her time in the company of Bach and Schumann, was though quite horrified by my taste, so I hid Freddy‘s records under my bed.

With my brother Berend on the cello, my violin teacher and stand-in father Hubertus Distler (in passionate Hungarian style) on the violin or viola, our house was a place for ‚proper‘ music, but as an aspiring seaman I felt I belonged more to the St. Pauli of Hans Albers.

My brother had a completely different outlook on life to me in those days and we mostly took care to avoid having to play together (or even set eyes on each other). It didn‘t help that he was much more industrious than me as a child and tended to spend the day tight in the lee of our mother, shadowing her every move and playing the man of the family (a role he eventually assumed for real much later on) despite being a right little chicken when it mattered.

Freddy Quinn indirectly came into my life again 20 years on when I joined Windpilot founder John Adam and Rolf Kaczirek, inventor of the Bügel anchor, to deliver Freddy‘s former pleasure cruiser Libertad to the Seychelles on behalf of the Sylt-based construction magnate who was taking it off his hands. Freddy’s stature as a cultural icon is a matter for others to debate; it was his physical stature that concerned us as we repeatedly banged our heads on door frames that had clearly been fitted with a shorter breed of sailor in mind. The boat, which had come into the world as one of the many small trawler-based warships („Kriegsfischkutter“) built for the German navy in WW2, enjoyed a renaissance under Freddy, metamorphosing into a chic venue for stylish receptions and a smart landmark on the Priwall Peninsula coast, which it seldom left until financial considerations persuaded the owner to sell it. Which is where we, the delivery crew, came into the picture.

But back to the harbour in Hamburg. When the banana boats steamed in from Ecuador, there I lurked down at the docks like some crazed monkey waiting for any ‘windfalls’ from unloading. Ships from Morocco meant oranges, which tumbled from their pallets by the crate load if the crane operator had hiccups or was otherwise struggling to maintain control. His loss was my gain as I scrambled for the glowing bounty and crammed fruit into my panniers until the tyres threatened to burst with the weight.

Arriving home, the same question always marched out to meet me: Are you sure you‘ve you doneyour homework? What a drag! I had plenty of freedom though and felt my trips to the docks were a noteworthy contribution as well as a bit of fun.

Logistics was the problem. There were uncles and aunts who would pay good money for a share in the delicious, nutritious bounty but the fruit was heavy, there was a limit to how much I could collect and obviously storing it was not really an option. The days of live vessel tracking still lay far in the future but shipping movements were advertised in the newspaper and I quickly familiarised myself with all the regular arrivals. I had my sales channels in place pretty quickly too but the potential for growth was always limited by what I could shift on my bike both from a practical point of view (Hamburg has very different standards to Bangkok in terms of what constitutes a reasonable load for a bike) and a safety point of view (I understood very well that the customs man‘s friendly wave as I passed could easily be replaced with hostility and legal complications if I pushed my luck too far). Sticking to regular but modest fruit runs seemed like the soundest policy.

The bike began to lose its appeal to cars when I hit ten and by eleven I was driving an Opel Rekord (three-speed gearbox and wraparound windscreen) around Hamburg sitting on a cushion.

My mother had very mixed feelings about this but her pride – and the practical advantages of no longer having to do everything herself when exhaustion left her wishing for nothing more than a chance to relax on the chaise longue obviously outweighed her worries in the end.

The Winterhude district of the city was my patch at that time and I saw myself as cock of the roost. I knew every tree and every crack in the pavement in our neighbourhood – and I kept a weather eye out for the cops, just in case they should risk in incursion into my ‘hood. My ego knew no bounds!

Reassuringly, once I was finally able (years later) to obtain a licence legally, I had no trouble doing so without any additional driving lessons. I even saved money on the test thanks to the examiner being one of my mother‘s patients: 70 Marks it cost me to enter the adult world and a full tank of fuel cost only 10 Marks – and lasted two weeks!

Cars, however, were nothing compared to the sea. I could hear it calling to me, feel it drawing me away. It came to dominate my thoughts completely and at 16, still a mere slip of a lad but powerless to resist any longer, I packed my bags and set off for maritime college to learn how to be a seaman.

Appropriately, the college was perched right by the water in Falkenstein with a view over the Elbe that comforted my soul. I spent three months there doing my best to pick up the skills I would need for the sea. Along with the Prüsse brothers and Hartmut Paschburg, I was one of just four students in my class who knew how to sail already. The rest still had mud on their boots.

Uli Prüsse, scion of the Hamburg harbour launch dynasty, we did our best to avoid lest he and his brother take exception to our presence. The sailing school on the Outer Alster Lake still bears his name, although he himself embarked on his final voyage a long time ago (may he rest in peace). He taught sailing very successfully for many years, wisely investing the proceeds in the finest sailing ship to be had anywhere in the entire region, Ashanti (later admired as Ashanti of Saba). Ashanti was – and is – an absolute beauty to behold and suited Uli in every respect. He tended to the taciturn, but then why would he need words when he had a yacht that spoke for itself ?

Hartmut Paschburg combined a slight figure with a sharp intellect and a natural flair for business. He rose to become a captain and on one long voyage years later happened to notice the legendary Sea Cloud, then named Antarna, lying in Panama in a dilapidated condition. He and a consortium of Hamburg businessmen bought her for a song, returned her to Germany with a crew of 40 in 1978 and sent her off to the Howaldswerke Deutsche Werft in Kiel for a refit. A year later, now the epitome of the floating luxury hideaway, the immaculate Sea Cloud returned to service. And some 40 years later she is still at it, a spectacular example of a square rigger successfully parting the wealthy from a modest portion of their assets in exchange for relaxed, no expense spared (golden taps in the bathroom) cruising under acres of canvas.

But none of that has anything to do with what I was up to in the mid-1960s. What I was doing was heading to sea. And finding out what dreams could do to a man who really wasn‘t one yet.

Had I forgotten that the sea was in my genes, that I was born to live my life largely out of sight of land? Not at all! That was my trump card, the argument non plus ultra with which I had finally quelled my mother‘s objections.

Already advanced in years by the time I was born, my father never played an active part in my childhood.

I knew him to be a man of the water though. A lecturer at the maritime college, he had been forceful in countering the (flawed) official line during the investigation into the loss of the Pamir, had served as an advisor to the Meyer yard in Papenburg well into old age and had left his mark on the profession with the stability calculations he produced for the Hamburg Ship Model Basin. My parents maintained a peculiar relationship of (largely) suppressed yearnings and desires, a relationship effectively directed by another woman who knew how wield all the weapons (financial included) in defence of her property with relentless intensity and feminine finesse until it – he – was rendered powerless to follow his heart any further.

It seems it was the same drama then as it is now when people who have grown apart accept a life in irons instead of walking away – crawling if necessary – or leave it too late to face up to the fact that they are staying only out of guilt or fear (and who put it there?) rather than any hope for future contentment. I speak here from experience and with the benefit of having eventually landed on my feet.

The result of all of this, sadly, is that I barely knew my father. My mother, on the other hand, was a talented writer who recorded her life meticulously on her Continental typewriter and archived the pages with scrupulous care in a series of robust box folders. I am hugely grateful to her for this as it has given me a sort of compass to navigate the past, a means to bring order to all kinds of recollections and find explanations for many things that my mind needed to have explained.

It was hardly surprising I heard the call of the sea ringing so clearly in my own ears, in other words. I wanted the ocean under my keel and I wanted to travel as far as possible. Most of all, I wanted (what‘s new?) to see the world and live life to the full.

No less surprising is the fact I ended up on a banana boat operated by the Laeisz shipping company, Hamburg‘s most prestigious, bringing every ape‘s favourite fruit (in fiction at least) to the people carefully chilled so that the yellow treasure would be in peak condition on arrival (unless the ship was delayed or the cooling failed, in which case it would be a foul brown mess).

The ships of the Laeisz company were famous the world over as Flying P-Liners, every one of which had a name beginning with P. The stories of mighty windjammers like the Pamir, Pisa, Potosi and Passat had been regular features in my childhood dreams even though I had no inkling back then that I had a family connection to the tale.

My very own gleaming Flying P-Liner sailed under the name MS Pisang and when it set off down the Elbe on the ebbing tide one day in 1964 on its maiden voyage with me among the crew, I felt like a real man at last (until I saw my mother waving me off from the Willkomm´ Höft, at which point the sudden realisation that I was leaving home and hearth perhaps for good turned me into a blubbering wreck).

Bananas for Japan were our standing orders, which meant a life criss-crossing the Pacific for the foreseeable future – years and years of it. That, at least, was the plan and when I realised the full implications, my teenage composure abandoned me completely.

My confidence took a mighty blow in those early days at sea as the pecking order and my place in it were brought home to me. Living in exclusively male company I found enormously tough and it scares me still to think how poorly equipped I was, both mentally and physically (fist-fights had never been my thing), to hold my own. My career moved on rapidly, all the way to the rank of ordinary seaman, but I was still bottom of the pecking order in a testosterone-fuelled environment full of irascible characters who knew but one real outlet for their pent-up frustration/boredom/rage/etc.

Eventually the coast of Ecuador would draw near, the pilot would come aboard with the all-important glossy laminated brochure of delights and they would be unleashed to spend some time in the sort of female company always to be found around the docks awaiting men in search of just that sort of female company. Our Second Officer Grauert did sterling work delivering large doses of penicillin into rear ends of the exhausted crew after every round of shore leave so that the poor souls had a chance to recover their health at sea before doing it all again at the next port of call.

The passage through the Panama Canal was an easy number: slow ahead and don’t hit the sides while trying to act confident and impress the pilot. Steering on this leg of the trip counted as a privilege and I certainly enjoyed it despite the jealous glances of crewmates whose skills at the controls were, well, better to suited to the open sea.

On leaving Panama at Balboa we headed off down the coast for a while before a hard left into the river and up to Guayaquil. Anchor down, launch alongside and off went 30 hungry seamen to pass the night on land – and in some cases the next day as well if the situation with the ladies allowed. The last few hands were always late back on board and in the meantime there was extra work for the rest of us. I was happy to fill in whenever necessary: extra hours were not exactly richly rewarded, but 150 hours of overtime a month added up to a decent sum.

It wouldn’t have bought me much time with the ladies, of course, but I had other plans and dreams for my cash anyway and it was the overtime hours that gave me a surplus to salt away and subsequently send home in preparation for new pursuits. I caught some flak from the rest of the below-decks crew for keeping my powder dry while they made new ‘friends’, but I was already beginning to realise our futures lay in different directions and was content to stand apart from the horde.

I particularly noticed the stark difference between the officers and the men. Up on the bridge, etiquette reigned supreme: officers were family men in crisp white uniforms and gleaming gold trim – calm and controlled and preoccupied with altogether more weighty matters like cargo, tides and the shipping company inspector, who would appear ghost-like around the corner if anything, even the smallest hint of rust, dropped our otherwise perfectly white banana boat below the impeccable standard expected of a Laeisz vessel.

The job of keeping all 136 meters of the Pisang up to scratch – which basically meant maintaining as-new condition – fell to us below decks. The task was literally endless. The rule was that whoever first noticed a problem, be it a fleck of rust on a railing or the unpleasant evidence of another crewmember‘s deficient skills with the toilet brush, was expected to fix it. Clearly this philosophy relies on the existence of a certain level of integrity among those to whom it applies. Generally, the men had no more interest in integrity of this sort than they did in philosophy and, being one of the lowliest life forms on board, it follows logically that I landed many of the choicest chores.

It seemed there was no part of the ship that couldn‘t be made even more perfect with a few hours of meticulous scrubbing (after which the first fleck of dust to return would stand out like a beacon and the process would begin again). It was a perfect environment for the type who likes vertical hierarchies and power games and has no understanding of how respect works.

The bananas were loaded by hand. Stem after stem came aboard via a seemingly endless stream of straining bent backs – and with the bananas, hidden away and unnoticed, came the multitude of spiders and snakes that would awake again, all at once, on leaving the cold store at the end of the voyage to make our life just that little bit more stimulating.

Brown and soupy, the Guayaquil River was no place for a swim, especially as there was always some creature or other, in or on the water, looking for something to bite. In the evening great swarms of locusts would rise out of the swamps and sweep into the city. Many met their end crashing into our ship, thence to be roasted by the cook or – if not quite dead – tucked away in some poor soul’s bunk for a laugh. It took more than that to wake me up, although a bucketful of salty water certainly did the trick if I overslept (and left my mattress in a fine state afterwards too). The fun and games never ceased – and never ceased to be thoroughly tedious if, like me, you were on the wrong end of them.

After weeks of loading, we finally set off West to bring the Land of the Rising Sun its dose of yellow delight. No sooner did we reach Japan than the testosterone kicked off again. The pilot brought with him a heavy folder full of photos in which sailors were invited to select their companion of choice and note the date and time at which they would like to be collected. I always thought the price excessive just for “a bath and shave”, especially as most customers seemed to be left, falling-down drunk and empty of wallet, to find their own way back to the ship. They certainly did end up clean though; Yokohama made a much smaller dent in the penicillin supplies than banana country.

So off went the bananas, back we went to Guayaquil and, three weeks on, the whole show played out again at the other end of the personal hygiene spectrum.

Seven times we sailed to Japan, along the way surviving typhoons and shivering in shorts in the Aleutians. Every lap started and finished at anchor off Guayaquil – where we roasted in the tropical heat waiting for the bananas to be ready, for one last load to come aboard and, on one occasion, for the four other Laeisz lines reefers ahead of us in the queue to be on their way. Temperatures could be anything up to 50 Celsius, the humidity up to 100 %. Rain, buckets of water or just plain sweat: one way or another we were always soaked through.

I spent my leave exploring the country in hired cars. I discovered that in Japan they drive on the other side of the road – but what was that to me, a man who had no driving license (yet) anyway? Visiting places like the Ginza district in Tokyo, I found that although the streets were heaving, someone of my height could enjoy a largely unobstructed view. Being tall was no help on the underground though – we were swept along in the human tide as much as anyone else. Taxis remained a privilege for the upper deck overlords in Japan but the fact they were a luxury too far for ordinary sailors like me did not stop me admiring their fully automatic doors: why has such a practical idea never caught on over here?

One fine day the Japanese charter arrangement went belly-up, the Pisang returned to Europe and my resignation letter landed as soon as the ship did. I had realised very quickly that this was not the career for me, but there was not much I could do about it in the Pacific with any potential flight home costing a fortune and me earning an hourly wage of peanuts. Thank goodness I didn‘t have to hold out for the full seven years of the original contract!

The story of going to sea: follow your genes – or your head – until you know better, then think again, swallow your pride and keep your head down until favourable winds return.

Thanks to my mother, a Steiner-minded school headmistress and my ability with the violin, I was able to fall back in with my old school class after my Pacific adventure. Tanned and toned but rather burned out and somewhat behind with my education, I managed to finish school successfully largely thanks to my violin playing and my ability to recount a good story. So much for formal education.

Back among normal people again, life was full of fun and I soon left all thoughts of my misadventures at sea behind. My time onboard ship left me fit and strong but on land I had control, a feeling I had all but forgotten during my time at sea (and not just because of the size of the vessel). Whatever ideas I may have started with, the reality extinguished my dreams of a career in the merchant navy for good. Life ashore was varied and exciting and I was ready to get on with living it.

It would be easy to blame youthful naivety for everything but I have a strong suspicion I would have followed the course to the same end even had I not been so ignorant of the world I was seeking to join. There was no other way: the wall was there and I was going to run into it! A natural single-hander with a burning need for independence, I can see now that life as a cog in the merchant navy machine was never going to work for me. I valued respect, genuine human connection and friendship – not the ideal qualifications for living cheek by jowl below decks in an exclusively male society with little more than random violence and the dubious pleasures of the oldest profession for variety.

The veil had been lifted, Freddy had been economical with the truth (who can a 16-year-old trust on such matters if not a singer from a landlocked country with no experience of working on ships?) and a year and half later here I was again older, wiser and no longer one for the sea.

Storm, Stress and Compulsion

Returning home from the sea with my tail between my legs, my first obligation was to keep a rather lower profile around the adults in my life. While undoubtedly very happy to see her lost son about the house again, my ever-shrewd mother could not help dishing me up a daily reminder of my career mistake and reiterating, complete with gestures of wisdom, that mothers know best. “I always knew a seaman’s life would not sit well with you!” If I heard that pearl once I heard it a thousand times – and there was nothing I could say in retort as there I stood, in the house not on the ocean.

Life for a time was thus largely a matter of keeping my head down and going with the flow. Resistance was unhelpful, not to say unreasonable. So I became the very model of politeness and did my best in every way to fit back into my old school class after so many months away. Sweetness and light it was not.

The headmistress of my school, who it seemed had a soft spot for me, had instructed that I go straight back in with my old classmates, an idea our class teacher found quite unacceptable. She saw me as a problem, a thorn in her side, a provocation in the purest sense of the word: deeply tanned, unruly hair, a full beard – I was nothing short of an outrage to this elderly lady for whom decorum was everything. The beard disappeared, but the affront behind it remained, shuffling uneasily on a chair right in front of her desk, and continued to rankle.

Come the end of the year I thought I had done enough to move up with the rest of my class, but now the old lady brought her influence to bear to try and compel me to resit. That, I felt, was quite out of the question and all educational levers were duly exploited.

I managed in the end to complete my “Abitur”, the school-leavers’ exam required in Germany in order to continue in education, in two and a half school years instead of the more usual three thanks in large part to my apparent prowess with the violin and my art teacher’s great enthusiasm for my creative output. Like Steiner schools generally, my school was more than happy to offset particular talents in one area against deficiencies in others, a situation I exploited with virtuoso panache as first violin in the school orchestra. It is almost as though my mother had some inkling of what was to come when she chose this particular school for me.

With the exams successfully behind me, life was good. The memories of less happy times at sea still remained fresh in my mind too, which only enhanced my enjoyment of the beauty of existence ashore (and of the beauties to be found there).

I never found school especially difficult; my problem was rather finding a way to fit school in around my extra-curricular activities. I, after all, had ground to make up in all areas of my education and not just in front of the books. Today I suppose it would just be put down to delayed adolescence: I spent my acne years at sea with only my thoughts and a bunch of aged (relatively) outcasts for company.

The Scent of Freedom

A strange and very useful thing happened to me when I was 18. One summer’s morning I put my portable radio in my pannier and set off on my bike for some time away, only to come home not with the bike but with a car, a Lloyd Alexander TS no less. Really! Along the way I came upon a certain Mr. Seel, who was spending his retirement presiding over a garage treasury full of old cars. Interpreting my longing looks correctly (if rather generously), he proposed a swap and I agreed and hence I returned from my holiday, bursting with pride, on four rattling wheels not two. I brought a crate of apples with me that I hoped would help placate my ever-temperamental mother.

(I still had much to learn about my mother, the main lesson being to stop underestimating her so comprehensively).

So, in the space of a week, I had mutated into a car-driving student, something I short-sightedly viewed as a privilege. Schools did not provide parking spaces for students in those days, so I had to park alongside my illustrious teachers, who thus earned the dubious honour every so often of having to help me push start my Lloyd (a heavy sleeper at times, especially in damp weather). The choke demanded a very fine touch: a fraction too much and the engine could be relied on to stop instantly.

Oh foolish youth, what imbecility led me to believe the object of young love’s (and lust’s) desire would be impressed by my new pink automobile? To my sweetheart, the daughter of a strict family of substantial means, this precariat’s car meant first and foremost embarrassment, an embarrassment she intended to avoid by never, ever, being seen in it by any of our fellow students. Thoroughly understanding of the doors her considerable charms could open, however, she also appreciated that it made for a comfortable – and thus tolerable and acceptable – journey home provided she could board away from prying eyes. Her parents always made me welcome too. They gave me lunch and I was happy to pay for the petrol in the hope of bigger rewards to come.

I certainly put in the miles, but progress came much more slowly than I had hoped.

Looking back, the whole experience provided a lesson in the intractability of such families and of the parents in particular, who would never let us out of their sight without a detailed breakdown of why, where and with whom. Their daughter eventually tired of her parents’ intellectual back and forth and took matters in respect of young Foerthmann into her own hands. This, however, proved to be a colossal mistake, the price of which amounted to a swift transfer to a different school (presumably a very strict one with no males in sight). Neither of us emerged any wiser from this debacle,