10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

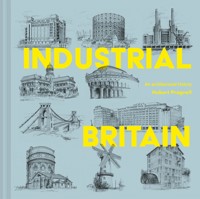

A fascinating insight into Britain's industrial past as evidenced by its buildings, richly illustrated with intricate line drawings. Industrial Britain goes far beyond the mills and machine houses of the Industrial Revolution to give an engaging insight into Britain's industrial heritage. It looks at the power stations and monumental bridges of Britain, including the buildings and engineering projects associated with the distribution of manufactured goods – docks, canals, railways and warehouses. - The gasworks - Temples of mass production - The mill - Warehouse and manufactory - Dock and harbour buildings - Water power and water storage - Waterways: canals and rivers - The railway age - Breweries and oast houses - Markets and exchanges - The twentieth century: industry on greenfield sites It's a story of industrial development, but also a story of its ultimate decline. As manufacturing has been increasingly replaced by services, new uses have been found for at least some of the country's great industrial buildings. Not least as containers for art and heritage, such as the Bankside Power Station (Tate Modern) and Salts Mill. Other buildings featured are still used as originally intended today, such as Smithfield Market in London and the Shepherd Neame brewery in Faversham. Illustrated throughout with over 200 original line drawings, Industrial Britain is a celebration of industrial architecture and its enduring legacy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 253

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

To Dorothea who still prefers a Queen Anne footstool to Battersea Power Station.

I would like to thank those who helped me in the writing of this book. To know what to put in or leave out is not easy and the knowledge of resident experts is essential. In particular I would like to thank Marilyn Tweddle and Grace McCombie for their advice on what to see in Durham and Tyneside; John and Marion Pearse for their wide knowledge of railway and canal buildings; Margaret Wade who alerted me to suitable buildings for inclusion in Lancashire; the staff at Gladstone Pottery Museum, Longton; Leeds Civic Trust and Anne Martin of Bristol Leisure Services.

I am also grateful for the expert eye of Simon Bradley with his up-to-date encyclopedic knowledge of English architecture gleaned through his editorship of Pevsner’s Architectural Guides for corrected points of dating, attributions and spelling. And finally but not least for Lilly Phelan at Batsford who has guided the revision of my book with patience and understanding, especially with last minute additions.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Britain’s industrial heritage

Fire, forge and furnace

The watermill and windmill

The power station

The gasworks

Temples of mass production: the mill

Warehouse and manufactory

Dock and harbour buildings

Water power and water storage

Waterways: canals and rivers

The railway age

Breweries and oast houses

Markets and exchanges

The twentieth century: industry on greenfield sites

Postscript

Bibliography

Index

INTRODUCTION

For many people, the study of architectural styles and influences means those relating to cathedrals, churches, country houses and perhaps castles. The idea of looking at factories, warehouses, mills, power stations or gasworks fills few with enthusiasm, conjuring up visions of soot-covered walls, prefabricated sheds, tall chimneys belching forth thick columns of smoke. Our memories might also be tainted with visions of the furnace-lit night skies of Sheffield, or noxious smells from chemical works, tanneries and breweries, or even the discharge of chemicals into rivers or canals. I have sympathy for this impression, and in Britain’s changing industrial climate much of this is true. However, if we accept this without question, an important part of our heritage may be lost along the path of wholesale redevelopment.

We rightly condemn what has become obsolete or insanitary and each century must make its own mark on progress. I do not wish to advocate that Britain should become an industrial theme park but that a happy balance should be struck in a world of increasingly rapid transition. In the nineteenth century Britain was a power whose industrial and social advances were the envy of much of the world. We had invented and developed steam power and the railway locomotive, made distances of hundreds of miles over land achievable within hours. Can it be right to destroy the buildings and landscapes that created our so-called greatness?

This book is the result of an interest in industrial buildings over many years. I was born within walking distance of the historic London borough of Greenwich, home to Inigo Jones’s Queen’s House, Wren’s Royal Hospital (then the Royal Naval College), Vanburgh’s neo-medieval ‘castle’ on Maze Hill, Hawksmoor’s St Alfege Church, Georgian terraces on Crooms Hill and the Gothic Revival Our Ladye Star of the Sea further up. The International Style Greenwich Town Hall brings us into the twentieth century and the medieval Eltham Palace is less than a couple of miles away. So, how was my interest in industrial buildings piqued? From the promenade in front of the Royal Naval College a vast panorama of industry opened up; to the east was Blackwall dominated by its gasworks power station and the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery on the horizon. Several hundred yards to the right was the huge Greenwich power station with its curious Gothic turreted chimneys. Looking westwards there was the Deptford power station and beyond that the Georgian terraces of the former Royal Victualling Yard. As a child I was fascinated by the atmosphere, smoky, yes, but full of life, with large cargo ships and tugs with trains of barges bringing produce to feed and fuel the warehouses, power stations and gasworks along the Thameside.

It was this environment of buildings of national importance and a skyline of chimneys, gas holders and brick warehouses that nourished my interest in architecture. Many architecture books in the shops and on library shelves of my childhood were about cathedrals, churches and country houses, and I wondered why the industrial side of our heritage seemed to receive little attention, at least until recent decades. I hope this book goes some way to showing the diversity of industrial buildings, some of which are Grade I or II* listed. Also, eight out of the 32 UNESCO World Heritage sites in Britain are former industrial sites.

BRITAIN’S INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE

Although textbooks tend to identify the start of the industrial revolution with Hargreaves’s Spinning Jenny in the mid-eighteenth century, records and remains of production go back centuries before this. Huguenot weavers settled in Kent and Sussex in the sixteenth century; two centuries earlier ironworks were set up in the Weald, producing anchors and primitive cannon. Until the middle of the seventeenth century most ships were probably built on beaches or excavated inlets from sea or river. However, with ships increasing in size, they began to be built in specially demarcated yards protected by wooden fences. By the eighteenth century these had become establishments of considerable size and included the royal dockyards of Chatham, Deptford, Woolwich, Sheerness, Portsmouth and Plymouth. Special buildings – stores, roperies, sail lofts and accommodation for senior dockyard officials – were developed. Similar establishments developed for the merchant fleet along the Thames, Tyne, Mersey, Forth, Clyde and numerous other rivers and estuaries. As ships continued to grow in size, some dockyards changed from shipbuilding to maintenance; some closed as newer and larger facilities took their place. While many dockyard buildings are merely functional, others reflect the taste and stylistic traits of an era, as in the massive brick gatehouse at Chatham, sometimes attributed to John Vanbrugh, master of the so-called English baroque.

As the textile industry developed, so the location of production changed from cottage lofts to spinning mills, many of which were massive – six or more storeys high – and often embellished externally. By the middle of the nineteenth century, mills and warehouses were adorned with classical, Gothic, and even Byzantine Egyptian motifs. Some became symbols of the prosperity of the company or, indeed, of the town. Chimneys were not simply a means of lifting the smoke well above the rooftops; they became towers piercing the skyline, square, octagonal, fluted, even in the form of a giant obelisk as at Marshall’s Mill, Leeds, or Saltaire Mill a few miles away.

By the 1830s railways were developing a form of architecture just as canals had done half a century earlier. Such was the confidence of the London and Birmingham Railway that their termini at Euston Road, London, and Curzon Street, Birmingham, were in the Grecian style. Thirty or so years later, the Midland Railway built its stations at London, St Pancras Manchester, and Glasgow in the Gothic. In the nineteenth century, even gas holders were contained within intricate cages of cast iron and steel, with girders punched with quatrefoils and shield motifs.

The electricity power station is perhaps the ultimate symbol of industrial blight on the British landscape – vast plumes of smoke emitted from tall chimneys and areas filled with coal stacks. Yet some had considerable character: Greenwich, with its turreted chimneys reminiscent of the domestic chimney stacks of Venetian palazzi; Battersea, which was to be the largest brick structure in Europe with a control room panelled in Italian marble, truly a temple of power.

By the end of the nineteenth century, industrial buildings were in the vanguard of the development and use of new materials. This went hand in hand with the quest for more light and fireproofing. In Germany, industrial design was pioneered by Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus in the early years of the twentieth century. The influence of Gropius’s Fagus Factory at Alfeld, with its metal-framed windows extending around corners without wall division, was soon to make its way to Britain and the factories of the new industries such as motor cars and aircraft, and the development along London’s Great West Road.

While the rapid industrialization of the nineteenth century typically resulted in squalid living conditions for workers, there were employers who realized the value of a clean environment for improving industrial production and developing loyalty in the workforce. Robert Owen’s model mill village of New Lanark (1808) was the first purpose-built attempt to provide an environment where workers and their families would be protected by the master. Children received schooling and a general store provided for all the needs of a family. From the 1850s, Titus Salt developed the mill village of Saltaire near Bradford, and towards the end of the nineteenth century came Bourneville near Birmingham, the Rowntree settlement in York, and Port Sunlight near Birkenhead, with neat rows of terraces in styles ranging from French Gothic to Cheshire vernacular, fronted by broad lawns, trees and a meandering stream. While Salt provided schools, a mechanical institute and an infirmary for his workers and their families, William Hesketh Lever, inventor of Sunlight Soap, provided an art gallery in the classical style for the mental refreshment of his workforce while their material refreshment was catered for by the temperance hotel.

By the early twentieth century, industry was moving to, or being developed in areas called industrial estates. Perhaps the first came as early as 1887 at Shieldhall on Renfrew Road, Glasgow, and from 1896 at Trafford Park, Manchester. The Slough Trading Estate (1918) and Dagenham (1931) were dedicated to the new industries: largely food at Slough, and motor cars at Dagenham. The architecture for the most part was plain and undistinguished; the showpieces were company headquarters in city centres or along the Great West Road in London.

Gone now is the need to build huge mills and warehouses: we have moved into an age of containerization and rapid transit. Where walls are still required, they are likely to be corrugated iron rather than rusticated stone blocks or multi-coloured brick courses pierced with Gothic windows and surmounted by swallow-tail crenelation. With massive redevelopment of the commercial centres of many towns and cities much industrial heritage has been lost. Many dwellers in towns and urban areas benefited from the 1956 Clean Air Act, which removed the constant pall of smoke that hung over them. The pottery towns of Staffordshire provide an excellent example: a skyline of smoking bottle kilns has been replaced with landscaped parkland. Some long-established pottery manufacturers still exist but their factories are models of modern technology using electric kilns.

In this introduction to our vast industrial heritage, I have taken the term to indicate buildings used for the production of commodities ranging from beer and flour to cloth and rope, or for the assembly of ships, railway locomotives and vacuum cleaners. I have also included buildings that serve industry and its transport needs. Many are hardly distinguished in terms of architectural quality and may not even be protected by listing. Some, however, are Grade II or even Grade I. Owen’s mill village of New Lanark and Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire are designated World Heritage sites. Windmills and watermills find a place, as do the giant cooling towers of a modern power station. The Custom House at King’s Lynn is included, as is the huge Corn Exchange in Leeds, both Grade I listed. Many more examples could have been included but for space.

It would have been impossible to mention every notable textile mill in Yorkshire and Lancashire, and one industry missing is that of coal. Building here was rarely more than functional and pit winding wheels are machines rather than architecture. In any case, with the destruction of the industry, all deep mines have been closed and most buildings razed to the ground. In some cases, the only evidence of a former mine is the surviving rows of terraced housing laid out in parallel back-to-back development. Ashington, north of Newcastle, is an excellent example.

It is to Cornwall that we must look for the remains of our oldest industry, the mining and export of tin that went back perhaps a thousand years before the Romans. Over two hundred ruined engine houses survive from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries before this industry went into sharp decline. Often found on cliff tops, these engine houses are a ghostly presence amid the gathering mists blown in from the Atlantic. These ruined structures acted both for pumping water out of the shafts and also for hoisting and crushing the tin ore. Like coal mining it was a perilous industry with a high mortality rate.

Looking for and at industrial buildings entails leaving the tourist track. Some of course, like power stations, dominate their locality; others, such as many railway buildings, are derelict with windows boarded up, awaiting an uncertain fate. The furnaces of eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century Coalbrookdale remain little more than brick and stone walls against the steep hillside, the coke ovens having long gone. Very few complete Staffordshire potteries survive; the buildings are derelict, and the few remaining bottle kilns sprout moss and creeper from the brickwork rather than black smoke from the funnel. The greatest cluster surviving is in Longton, including the Gladstone Pottery Museum. The explorer or enthusiast must be prepared for decay, dereliction and disappointment.

Although, in some cases, our industrial heritage is still being destroyed, there are some remarkable surprises to be found – the Granary on Welsh Back, Bristol, is worth a long pilgrimage, having survived both bombs and redevelopment. St Paul’s House, a warehouse in Leeds is now offices and makes a striking impact in a city still rich in industrial monuments, and with a positive policy of restoration. Some of the docks and adjacent warehouses in Liverpool have been restored, although there are still thousands of acres of redundant industrial land in Merseyside. Here and there dock pumping stations from the romantic but functional imagination of Jesse Hartley survive. These can only be reached on foot, and with determination. In London, the conversion of Bankside Power Station into Tate Modern was both creative and imaginative. Nearby, Battersea Power Station is being restored at the heart of a mixed housing and entertainment complex.

I hope that in my invitation to look and explore, the reader will be greeted with a few surprises. Take a camera or sketchbook before it is too late.

Ashington, Northumberland: Woodhorn Colliery.

Historians usually cite Coalbrookdale in Shropshire as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, but this is to dismiss the magnitude of the earlier iron industry in the Weald of Kent and Sussex that had developed even before the Roman occupation. It is believed that this began around Wadhurst in the High Weald, which was rich in iron-bearing clay, charcoal from the extensive forests, and water from the numerous streams feeding into the Medway and Rother. By the Tudor period the industry was expanding rapidly. Blast furnaces generated sufficient heat to liquefy the iron and so produce cast iron. The other major iron-producing area in Britain was the Forest of Dean in the west of England. The most important products produced by the industry from this period were cannon and anchors, and large numbers of men must have been employed. However, nothing of this survives except the sites of several gun-casting pits, as at Cowden and Wynch Cross in East Sussex. The Weald’s industrial revolution has left no relics.

Around 1700 Coalbrookdale became the centre of the Industrial Revolution when Abraham Darby I, a Bristol foundry owner, perfected ‘the art and mystery of casting and moulding of iron pots’. From manufacturing cast-iron kitchen pots and kettles, the business progressed over the next hundred years to casting components for Matthew Boulton’s steam pumping engines for the mines and mills at Soho, near Birmingham and, most famously, the iron sections for the bridge across the Coalbrookdale gorge, designed in 1775 by Shrewsbury architect, Thomas Pritchard.

The attraction of this area of the Severn Valley was the supply of coke, which was burned with ironstone instead of charcoal. The Severn was navigable from Coalbrookdale and therefore within easy reach of the seaports of the Bristol Channel. And the steepness of the locality made possible a system of streams from the Coalbrook to turn the waterwheels that powered the blast-furnace bellows and forge hammers. The ironstone and limestone pits were above the furnaces so ore was brought down the steep hillside to the furnaces on iron railways. From the furnaces the castings were taken further down the hillside to riverside wharfs for conveyance downstream by barge (and from the last decades of the eighteenth century by feeder-canal to the Midlands and the south). Just south of the village of Ironbridge on the east bank of the Severn the ruined Bedlam furnace survives, and in the nearby valley the remains of the Blist Hill furnace are a powerful reminder of when this part of England led the world in the development of iron casting.

1 Coalbrookdale, Shropshire: the remains of the Bedlam furnace, which was the location of the famous painting by Philip de Loutherbourg, Coalbrookdale by Night.

2 Coalbrookdale: Blist Hill blast furnace built in the 1830s. Iron ore, limestone and coke were brought on the canal and fed into the tops of the furnaces. Continuous blasts of air at the bottom allowed combustion to occur. In the intense heat the iron would melt out of the ironstone and run to the bottom of the furnace and into the casting house, a brick building, in which a series of channels would be made. Into these molten ore would flow, to be cast into blocks. The waste (slag) flowed on top of the metal and could be drained off.

3 Rowlands Gill, Co. Durham: Derwentcote Steel Furnace. Restored eighteenth-century furnace in which bars of wrought iron packed with powdered charcoal were heated.

While the Iron Bridge is justifiably classed as architecture of worldwide significance, few of the other eighteenth-century buildings in the gorge were anything but functional, and are now ruinous or incomplete. Although heavily restored, one of the finest eighteenth-century furnaces remaining is the Derwentcote Steel Furnace in County Durham. Built of local stone, the furnace itself is set within a central chamber, which tapers above like a funnel. When it was built, this part of northeast England was not only on the edge of the oldest coalfield, with Newcastle as the main port, but there were still extensive woodlands for charcoal.

Lime burning was once an extensive industry, producing lime for both agriculture and building. Like furnaces, lime kilns are usually purely functional. A number of examples survive, often in heavily overgrown locations. One nineteenth-century example is at Duncton in the Sussex Weald. Here the wall of stone is inset with three brick arches, the middle one infilled with flint, the effect strangely awesome, even creepy, like antique Roman remains in a Piranesi engraving. At Beadnell Harbour on the Northumberland coast there are eighteenth-century kilns remaining in a good state of repair. Constructed of large blocks of stone, they have a fortress-like quality. The top is like a rampart with an opening to the furnaces beneath, into which the stone was dropped. There were also back-flues to help draw the fires.

1 Duncton, West Sussex: remains of nineteenth-century lime kiln, constructed of flint and rubble stone. The arches are of brick.

2 Beadnell, Northumberland: eighteenth-century sandstone lime kilns.

3 Diagram of a typical lime kiln.

Brick-making was indispensable to the growth of nineteenth-century towns and cities. The Romans had built extensively in brick, but it was not used again in Britain until the late Middle Ages. Little Wenham Hall in Suffolk (c. 1260–80) is perhaps the earliest building in brick in England but the bricks used were imported from Flanders. Brick-making is recorded at Ashburnham, East Sussex, as early as 1382; just over a century later, Cardinal Henry Moreton commissioned the completion of the rebuilding of the crossing tower (Bell Harry) of Canterbury Cathedral with an inner core of brick from east Kent clayfields. Kirby Muxloe Castle, Leicestershire (1480–4), is built of local east Midlands brick.

The great Tudor houses were made of stone, using brick where stone was not readily available, and the use of brick for ordinary domestic building did not become widespread until the middle of the seventeenth century, hastened by a number of major fires, including those of London and Warwick.

The brickworks of the south-east are in many instances little more than overgrown ruins. Where production has been moved to large-scale sites – such as those in Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire – the buildings are little more than functional kilns, ovens or chimneys.

SHOT

Shot towers were once familiar buildings on the industrial skyline. The best-known, if in disguise, was that on the south bank of the Thames adjacent to Waterloo Bridge, which was integrated into the Festival of Britain in 1951 and demolished a few years later. Few survive today. The oldest is that of the former Walkers, Parker & Co. leadworks in Chester, built around 1800, to use the lead ore from the mines of north Wales. Here shot was made in all sizes to cover the needs of artillery, the navy and rural pursuits including hunting.

The circular tower in Chester, like that at Waterloo, is made of brick and tapers to a platform more than 50 metres (165 feet) above ground. Here the lead was heated in an oven and dropped through a perforated brick floor into vats of water at ground level. This method of producing shot was invented by William Watts, a plumber in Redcliffe, a Bristol suburb. He experimented by building a tower above the roof of his house, the height of which gave the lead droplets or globules, mixed with traces of arsenic and antimony, sufficient fall to produce the necessary degree of roundness and solidity before hitting the water vats below. The oven was a fire hazard to this and other towers, the platform being reached by a staircase of sandstone, but originally of wood, spiralling up the inside walls. The appearance of the tower, finished by a crenelated parapet, has been somewhat marred by the introduction of a lift shaft behind corrugated-iron sheeting in about 1900. Intermediate testing platforms for various grades and sizes of shot are marked externally by bands of varied brick coursing.

Appropriately, since the earliest shot tower was set up in Redcliffe Hill, Bristol, in 1782 and survived until 1968, there is a modern concrete replacement designed by E A Underwood in nearby Temple Marsh, built in 1969. With its polygonal summit containing a glazed gallery, it looks like a futuristic lighthouse. It even received a Civic Design Award from Bristol Civic Society in 1969. The production of shot ceased in the late 1980s and the tower has been converted to form the centrepiece of a commercial development.

1 Chester, Cheshire: shot tower for former leadworks, Walters, Parker & Co. built c. 1800.

2 Bristol, Cheese Lane shot tower: built of reinforced concrete, c. 1969, it broods over the Temple Marsh area like a watch tower.

GLASS

One of the most vital industrial commodities is glass, yet few buildings for its production are of real architectural merit. As an industry it grew in importance from the sixteenth century. By 1700 in Newcastle, it ranked second to coal, with an established trade with London. By this time the windows of most houses were filled with glass and the Lower Thames rivalled the Tyne for the number of glassworks. One was described by the diarist John Evelyn in June 1673 as the ‘Italian glasse house at Greenewich, where was glass blown of finer metal than that of Muran’. The Duke of Buckingham owned a works at Greenwich, as well as others at Lambeth and Vauxhall, for the production of crystal glass. A vital part of glass manufacturing is the supply of sufficient brick for the kilns, timber for the furnaces and white sand, and for this writer Daniel Defoe praised the Kentish sand as the ‘best in England’. There was also extensive glass production in the West Weald in Sussex with its plentiful supply of sand and charcoal.

Glassworks were originally identifiable by their groups of tall, cylindrical, brick-built kilns – not unlike potteries. Small communities developed around some kilns, as at Wordsley near Stourbridge, West Midlands, or the much larger one around Pilkington’s at St Helens, Merseyside. Modern technological methods of production mean that giant furnace kilns are becoming rarer, or, as in the case of the former GEC glassworks at Lemington, a suburb of Newcastle, the only reminder of a once-thriving local industry. At least 30 metres (98 feet) high, it tapers gracefully to a square opening set within the circular rim. From the inside it can be seen that the walls are set back in stages every 6 metres (20 feet) or so as they thin towards the summit. This is to distribute the greatest weight to the lowest stage.

1 Lemington, Newcastle: the last surviving glass-making kiln, c. 1797, of the once-flourishing Tyneside glass industry. It has recently been turned into a car showroom.

2 Alloa, Fifeshire: surviving bottle kiln.

Bristol was also the centre of a thriving glass manufacturing industry with over a dozen brick kilns dating from the late eighteenth century. There was a plentiful supply of sand, limestone and red lead available locally. Only one kiln survives today, from the Prewitt Street Glassworks. It had gone out of use by the early nineteenth century. Originally about 50 metres (165 feet) high, it was reduced to around 10 metres (33 feet) in the 1930s due to cracks in the brickwork, and only survives today by being incorporated into the Hilton Hotel complex as a restaurant. Circling the base of the kiln are arches divided by splayed piers creating a stilt-like effect and which have access to the furnaces. Unfortunately all the brickwork above these arches has been covered by tiling.

The oldest surviving glassworks in Britain is at Alloa, Fifeshire, founded by Lady Frances Erskine of Mar in 1750 where the north brick cone survives. Craftsmen were at first imported from Bohemia, a renowned glass-producing region. Although only one of two large brick kilns survives, the works, now the largest in Britain, produces about a million bottles a day. The only other complete cone is at Catcliffe in South Yorkshire, dating from the 1740s.

POTTERY

Pottery is the industry that gave its name to a location in the Trent Valley, mid-Staffordshire, from the 1760s. Until the 1970s it was dominated by brick kilns, some tall, some squat, belching black smoke. The major centres were Stoke, Hanley, Fenton, Longton, Burslem and Tunstall, the so called ‘Six Towns’. Major potteries were also founded at Worcester in 1751, and at Coalport on the Severn in 1796. The initial development of the area was due to the presence of coal measures interspersed with beds of marls and clays from which coarse earthenware was made. This belt along the Trent Valley was linked to the port of Liverpool and the Mersey estuary with the construction of the Trent and Mersey Canal, started in 1766. This was used to transport kaolin or china clay from Cornwall and flint from Devon, which had been unloaded in Liverpool. China clay was an essential ingredient in the fine glazes developed by Josiah Wedgwood at his factory built between 1767 and 1773.

The industry had developed over the previous hundred years before the opening up of the coalfield using charcoal from the Midland forests. The potworks, or potbanks as they were to become known, were rather like cottage industries developed around farmsteads. The local clay was mixed in the open and the kiln erected as a brick addition to the farmhouse. The fired wares would be stored in a barn. With the expansion of the industry, by the middle of the eighteenth century, purpose-built buildings were erected, usually around a courtyard. These included a kiln, throwing house and warehouse. Larger companies had workshops for making the clay tubs, known as saggars, which protected the wares during firing. From the 1780s steam engines were used to drive clay-preparation machinery, a second consumer of coal, along with the kilns. Other buildings might include a dipping house, where the glazes were applied between firing, and separate firing kilns. The front to the street or canal might be more imposing, in keeping with the new image the industry wished to create as it tried to overtake the market hitherto held by continental firms in Germany, Holland, and especially France.

1 Longton, Stoke-on-Trent: Gladstone Pottery Museum.

2 Coalport on Severn, Shropshire: surviving kiln and restored buildings of the famous porcelain factory, founded in 1796.

3 Cut-away diagram of a bottle kiln.

A classical touch was given by Josiah Wedgwood who named his factory at Burslem ‘Etruria’ after the ancient Etruscans who had produced a reddish earthenware, and whose figurative and patterned designs were a source of inspiration to artists and craftsmen for much of the eighteenth century. From 1773, when he completed a vast dinner service for Catherine the Great of Russia, Wedgwood’s reputation was secure. As well as his comparatively plain, cream-coloured earthenware (Queen’s ware), he introduced his celebrated white and blue porcelain (Jasper ware) adopting classical motifs from pattern books and his friend, the architect Robert Adam. As his epitaph in Stoke says, he ‘converted a rude, inconsiderable manufactory, into an elegant art and an important part of national commerce’.

The Wedgwood factory at Burslem had a formal frontage beside the Trent and Mersey Canal. Designed by Wedgwood and a Derby architect, Joseph Pickford, it might be described as modified Palladian. The brick frontage, which, like those of most pottery manufactories, hid a collection of rather undistinguished if very practical buildings behind, had a projected centrepiece containing a tall stone arch set into the brickwork and a gable at roof level acting as a modified pediment. The façade was three floors high and surmounted by a tile-clad roof. This building housed the company offices, and display and buyers’ rooms. In the centre, that is, behind the pediment, was a hexagonal lantern. Pickford was also commissioned by Wedgwood to design his nearby country house, Etruria Hall (1767–71). In the restrained Palladian mood with a dominating central block crowned with pediment, and lower flanking wings, it once stood in open country but is now engulfed by industrial squalor and decay.