Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Spurbuchverlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Inflection

- Sprache: Englisch

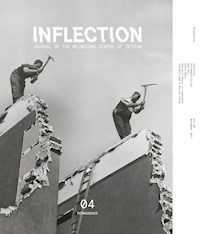

Permanence as an architectural concept is no longer restricted to the Vitruvian virtue of firmitas. To think about it in this sense today produces a schism: absolutism in a world of relativism. The fourth volume of Inflection extrapolates the permanent and the temporary not as opposing forces, but as a spectrum to be navigated at each stage of architecture's unfolding narrative. Through each of the responses presented in this year's edition, Permanence provides a critical voice as architecture and design continually seek an enduring foothold in an inherently evolving landscape, physical or otherwise. Inflection is a student-run design journal based at the Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne. Born from a desire to stimulate debate and generate ideas, it advocates the discursive voice of students, academics and practitioners. Founded in 2013, Inflection is a home for provocative writing—a place to share ideas and engage with contemporary discourse.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Inflection JournalVolume 04 - PermanenceNovember 2017

Cover Image:Wrecking the Seat of Learning Argus Newspaper Collection of Photographs, State Library of Victoria

Inflection is published annually by the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne and AADR: Art Architecture Design Research.

Editors:

Dominic On, Jessica Wood, Nina Tory-Henderson and Stephen Yuen

Deputy Editors:

Catherine Woo and Olivia Potter

Academic Advisor:

Dr. AnnMarie Brennan

Academic Advisory Board:

Dr. AnnMarie Brennan

Prof. Alan Pert

Prof. Gini Lee

Acknowledgements:

The editors would like to thank all those involved in the production of this journal for their generous assistance and support.

For all enquiries please contact:

inflectionjournal.com

facebook.com/inflectionjournal/

instagram.com/inflectionjournal/

© Copyright 2017

ISSN 2199–8094

ISBN 978-3-88778-520-8eISBN: 978-3-88778-913-8

AADR – Art, Architecture and Design Research publishes research with an emphasis on the relationship between critical theory and creative practice.

AADR Curatorial Editor: Rochus Urban Hinkel, Stockholm

Production: pth-mediaberatung GmbH, Würzburg

Publication © by Spurbuchverlag 1. Print run 2017 Am Eichenhügel 4, 96148 Baunach, Germany.

Graphic design in collaboration with Büro North Interdisciplinary Design

No part of the work must in any mode (print, photocopy, microfilm, CD or any other process) be reproduced nor – by application of electronic systems – processed, manifolded nor broadcast without approval of the copyright holder.

The opinions expressed in Inflection are those of the authors and are not endorsed by the University of Melbourne.

CONTRIBUTORS

Aki Ishida

Aki Ishida is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. She founded Aki Ishida Architect PLLC in New York City, and prior to that, worked at the offices of Rafael Viñoly Architects, James Carpenter Design Associates and I.M. Pei Architect. In 2016, she was recognised nationally as one of the 25 Most Admired Educators by DesignIntelligence.

Amelyn Ng

Amelyn is a recent graduate of the Melbourne School of Design. She is now a graduate architect at Fieldwork and an independent writer whose work has been published across a variety of digital and print Australian media. She recently presented papers on civic agency and socially responsive infrastructures at conferences in Philadelphia, USA and Nicosia, Cyprus. Amelyn will be moving to New York City later this year for further study in architectural criticism at Columbia University.

Barnaby Bennett

Barnaby Bennett is a publisher and co-founder of Freerange Press. He is an award-winning designer, and is currently completing a PhD examining the political characteristics of temporary architecture in post-quake Christchurch. Barnaby has been widely published and teaches architectural theory and design at universities in Australia and New Zealand.

Casey Mack

Casey Mack is an architect and the director of Brooklyn-based Popular Architecture, an office devoted to combining simplicity with versatility in work across multiple scales. With the support of the Graham Foundation, Mack is currently writing Digesting Metabolism: Artificial Land in Japan 1954–2202, a forthcoming book from Princeton Architectural Press on built housing by the Metabolists and their associates inspired by Le Corbusier’s unbuilt designs for Algiers. Mack’s work has been published in Domus China, CLOG, The Avery Review, Bracket and OASE.

Christine Bjerke

Christine Bjerke is an architect, designer and educator based in Copenhagen, Denmark. She holds a Diploma of Architecture from the Bartlett School of Architecture and a Bachelors of Architecture from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. In 2015 she co-founded the interdisciplinary collective In-Between Economies and she is the editor of the multifaceted website and publication project, www.thefxbeauties.club. She is currently teaching the Urbanism & Societal Change Masters Programme at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

Christof Mayer

Christof Mayer studied architecture in Berlin and London. He graduated in 1998 from the Technical University of Berlin. In 1999, he founded the architecture collective raumlaborberlin with Andrea Hofmann, Jan Liesegang and Markus Bader. In 2000, he became a member of the Chamber of Architects Berlin and started the Büro für Architektur und Städtebau. He has since taught in Germany, Switzerland, Norway, Greece and Australia. In 2014, he held a residency at Monash University in Melbourne. Since 2017, he has held a professorship at the Bergen Architecture School in Norway.

Dan Hill

Dan Hill is an Associate Director at Arup, the global design and engineering firm. He is Head of Arup Digital Studio, a multidisciplinary strategic design, service design and interaction design team. Dan is uniquely positioned at the intersection of design, urbanism and technology, and is recognised globally as a key thinker, leader and practitioner in this field. Dan is an adjunct professor at RMIT University and UTS and a visiting professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture.

Eleni Bastéa

Eleni Bastéa was born and grew up in Thessaloniki, Greece. She holds a BA in art history from Bryn Mawr College, and a Master of Architecture and a PhD in architectural history, both from the University of California at Berkeley. At the University of New Mexico, where she has taught since 2001, she is Regents’ Professor of Architecture and director of the International Studies Institute. The recipient of several grants and awards, she lectures internationally on memory and architecture, cities and literature, and on modern Greece and Turkey.

Elizabeth Diller

Elizabeth Diller is a founding partner of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), an interdisciplinary design studio that works at the intersection of architecture, the visual arts and the performing arts. DS+R focuses on projects of civic importance: rethinking the future of the city, the changing role of institutions and the increasing dominance of technology in society. She is also a Professor of Architecture at Princeton University.

Jessica Wood

Jessica Wood is an editor of Inflection Journal and a Master of Architecture student at the Melbourne School of Design. She holds a Bachelor of Interior Design from RMIT University, where she also teaches Design Studio. In 2014 she was awarded the Australian German Association’s Travel Fellowship.

Kaylene Tan

Kaylene is a PhD student at the Melbourne School of Design, focusing on food heritage interpretation. With a background in heritage engagement, Kaylene has worked as a writer and producer for film, audio, theatre and site-specific performances for cultural organisations and historical sites in Singapore and Malaysia.

Morgan Hickinbotham

Morgan graduated from the Victorian College of the Arts in 2012 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts, majoring in photography. His photography work spans the fashion, design, architecture and commercial spheres. Seeing and thinking in sound and vision, he also makes music and video art.

Sean Anderson

Sean Anderson is the Associate Curator for the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Prior to his work at MoMA, Anderson served as the undergraduate program director and senior lecturer of design and history at the University of Sydney from 2012. His research focused on Italian modernism and its effect upon colonial and post-colonial architecture across multiple geographical contexts.

Tanja Beer

Dr. Tanja Beer is an award-winning ecoscenographer and an Academic Fellow in Performance Design and Sustainability at the Melbourne School of Design. She has more than 15 years professional experience, including creating ephemeral designs for projects in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, New York, London, Cardiff, Glasgow, Vienna and Tokyo.

Toby Dean

Toby Dean graduated from the University of Melbourne in 2017 with a Master of Architecture and now teaches in the Bachelor of Environments. He is interested in the intersection of contemporary culture with tradition and in seeking alternative methods of architectural practice and exhibition for the future. He believes in design as a form of empowerment and hopes to continue the discourse on the implications of architecture upon complex environmental and social systems.

Tod Williams and Billie Tsien

Tod Williams and Billie Tsien began working together in 1977 and co-founded their eponymous architectural practice in 1986. Located in Midtown Manhattan, their studio focuses on work for institutions including schools, museums and not-for-profits—organisations and people that value issues of aspiration and meaning, timelessness and beauty.

CONTENTS

Editorial

Barnaby BennettBreaking and Making Temporality

Christof MayerCui Bono? The City as a Product of Societal Negotiation

Aki IshidaMetabolic Impermanence: The Nakagin Capsule Tower

Kaylene TanUnfinished: Brutalist Heritage in the Making

Casey MackFuture Stock

Dan HillOn Systems

Amelyn NgIllusions of Freedom

Christine BjerkeDual-Living: The Digitalisation of Domestic Space

Elizabeth DillerOn Obsolescence

Tod Williams and Billie TsienOn Slowness

Eleni BastéaThe Memory of Loss

Tanja Beer*The Aesthetics of Impermanence

Toby DeanThe Reassembled Town Hall

Jessica WoodMPavilion: Catalyst or Cat’s Paw?

Sean AndersonOn Imagined Placelessness

*denotes articles that have been formally peer-reviewed

EDITORIAL

Dominic On, Jessica Wood, Nina Tory-Henderson and Stephen Yuen

Permanence has long been prescribed as an essential virtue of architecture, associated with the Vitruvian definition of firmitas. mass and solidity crafted to endure. Yet, to think about architectural permanence in the Vitruvian sense today produces a schism: absolutism in a culture of relativism. Speculative development, volatile real estate markets, international warfare, mass migration, a changing climate and throw-away attitudes prioritising quick and temporary fixes for ongoing problems have repositioned the value placed on the material durability of architecture. How do we focus our thoughts and efforts in a culture of obsolescence, when the very essence of architecture—to build—has endurance at the centre of its logic?

This logic frames the architectural project as complete the moment it is built, but a building is an ongoing series of processes; it changes over time through occupation, inhabitation and developing technologies. From the enduringly incomplete Tower of Babel to the temporary urbanism of today, practitioners and theorists have been negotiating and reinterpreting the definition and value of architectural permanence, and it is in this milieu that this edition of Inflection is positioned.

In opposition to the commonplace acceptance of architectural timelessness, this journal presents alternative practices that interrogate the relationships of architecture and design with solidity and time. Through examining a series of temporary architectural interventions in post-quake Christchurch, Barnaby Bennett proposes an ecological understanding of architectural timescales. He argues that buildings should not be understood as inert edifices, but as ‘living’ things that respond to flows, shifts, events and activities as they move through time. In rebuttal to the scrap-and-build culture in Japan, Casey Mack’s study of ‘artificial land’ projects by structural engineer Toshihiko Kimura underscores the importance of cultivating new attitudes toward existing built stock in order to project them into the future, finding a middle ground between permanence and change. Christof Mayer of raumlaborberlin takes post-Wall Berlin as a case study to illustrate how temporary projects can democratise spaces, diversify a city and contribute to long-term urban developments. A thesis project by Toby Dean from the Melbourne School of Design explores the reclamation of public space through more permanent means. Dean proposes the Reassembled Town Hall as a tool with which to resist a culture where the worth of architecture is reduced to economic capital alone. Conversely, in the fields of scenography and performance design, the transience of the event typically takes precedence over the fixity and sustainability of the set and costumes. Tanja Beer’s research considers the social and environmental ripples that resound long after the curtain falls and the set is demolished.

Our contemporary world is one in-flux; new technologies allow business models, governments and social structures to morph with unprecedented speed. How then, does the relatively slow and fixed practice of building position itself in this global condition of temporal, social and technological instability? Amelyn Ng responds to this question through a critique of the rise in freelance and precarious work, made possible by contemporary conditions of globalisation, digitalisation and fluctuating economies. In exploring the spatial implications of our changing work life, she puts forth a sharp commentary on the now ubiquitous hot-desk environment. In a hive of infinite connectivity and productivity, our work life is increasingly held in a state of temporality and placelessness, resulting in a nostalgia for permanence. Christine Bjerke examines the digitalisation of the home and the subsequent effects of destabilisation: breaking down perceived boundaries of domesticity and privacy. Whilst technologies have transformed the social space of the domestic, she posits that the physical space of the home remains largely unaffected, and subsequently questions how the materiality of the home might respond.

An enquiry into architectural permanence is not only an exploration of physical and material endurance, but also of cultural and symbolic persistence. It prompts an investigation into what our architecture says about our collective psychology across time and cultures. Never intended to be permanent, initially considered irreparably ugly and out of character in its romantic surroundings, the Eiffel Tower has since come to define the ‘concept’ of Paris. But of the 18,000 iron members which make up the tower, each has been replaced at least once. The Eiffel Tower as it stands today is a facsimile both of itself and of the culture it has come to represent. So when it comes to architectural heritage, do we seek to preserve the buildings themselves or rather the ideals, souls and epochs by whom they were conceived? As creatures with imperfect memories, perhaps the practice of designing, building and restoring enables us to convert urgent shortterm phenomena into physical recollections thereby cheating our fated collective anterograde amnesia.

Taking Brutalism as a case study, Kaylene Tan uses a movement in a kind of architectural limbo, neither contemporary nor solidified in the past, to question the role of heritage protections. How do we decide what to preserve when our definition of ‘heritage’ changes from person to person, from age to age? Heritage should be considered a verb rather than a noun. If undertaken merely as a formal exercise concerned with hermetic histories and aesthetics, heritage fails to serve modernity. Rather a building’s ‘permanence must be earned rather than merely assumed’ through continual use and appreciation. In a close reading of the current situation surrounding Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, Aki Ishida delves into the broader cultural and historical beginnings of Metabolism to find answers to the Tower’s preservation conundrum as a building designed to evolve. In The Memory of Loss, Eleni Bastéa poetically explores the symbiotic relationship between buildings and memory. Physical reference points act as a backdrop for the recollection of one’s life, and so these buildings in our memory maintain a legacy and life form after their demolition. Only when physical heritage fails and buildings are wiped away is permanence ultimately achieved. Like our ancestors, buildings are untouchable in death.

Preservation through memory is not confined to introspection. Often, the decision to demolish a building provokes a social and political commentary which can continue well after the dust settles. A tension exists between the need to develop and the need to value cultural history. The 2014 demolition of the 15-year-old American Folk Art Museum in New York is one such example which has sparked a polemical discourse amongst the architectural community and the greater public. To this day, the lingering effects of MoMA’s decision are still at work as the institution continues their plans for expansion. The journal presents a multivocal view on the situation. In an interview with the architects of the Folk Art Museum, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, they expound upon their design approach which involves a deliberate slowing down in a world which prioritises speed and efficiency. Elizabeth Diller from interdisciplinary design studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro, chosen to lead the development and expansion of MoMA, provides an alternative perspective, acknowledging our contemporary culture of obsolescence.

Through these voices, Inflection Vol. 4 extrapolates the permanent and the temporary as a spectrum to be navigated at each stage of architecture’s unfolding narrative. Through each of the responses presented in this year’s edition, Permanence provides a critical voice as architecture continually seeks an enduring foothold in an ever evolving landscape.

01Cedric Price, Re:CP, ed. Hans-Ulrich Obrist (Basel: Birkhauser Verlag AG, 2003), 11

Photograph by Mark Strizik.Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria

BREAKING ANDMAKINGTEMPORALITY

TIME AND TEMPORARYARCHITECTURE INPOST-QUAKE CHRISTCHURCH

Barnaby Bennett

What makes one thing permanent and another temporary? Can objects, buildings, or landscapes be understood through other forms of temporal status? And how might these different forms affect our experience of the objects? This essay seeks to answer these questions by complicating the normally tidy division between the permanent and the temporary by articulating an ecological understanding of time that encompasses a broader range of temporal conditions.

The difference between temporary and permanent things appears self-evident: the former exists for a discrete and measurable amount of time, whilst the latter extends into the future. This is one of the binary divisions we use to understand the status of objects in the world, and we build relationships with things based on these assumptions. This essay is based on information gathered whilst living in Christchurch between 2012 and 2015. Assumptions of permanence and temporariness were particularly evident when dealing with the built environment after the earthquakes in 2010 and 2011. At 12:51 p.m. on 22 February 2011, a large earthquake shook Christchurch, New Zealand’s second largest city.

Between September 2010 and the end of 2012, over 13,000 earthquakes jolted the city of 342,000 people, but the February 2011 quake was different. The city was devastated— buildings and infrastructure were damaged and 185 people were killed.1 A national state of emergency was declared the following day: the core of the city was shut down and cordoned off as a public exclusion zone. It would be over two years before citizens could return freely to the shattered city centre. In this context, the temporary became necessary and the permanent visions of the city a topic of controversy and debate.

In his 1997 essay ‘Trains of Thought’ Bruno Latour compares the experiences of two twins.2 The first is moving slowly through the jungle. Latour says ‘She will remember it because each centimetre has been won through a complicated negotiation with other entities, branches, snakes and sticks that were proceeding in other directions and had other ends and goals.’3 A second twin is travelling on a fast TGV train from Paris to Switzerland. ‘… he will remember little else except having travelled by train instead of plane. Only the articles he read in the newspaper might be briefly recalled … No negotiation along the way, no event, hence no memory of anything worth mentioning.’4 Latour uses these examples to contrast experiences—to show the sweat, exertion and suffering of establishing a new path through the jungle against the ease and relaxation of sitting on a train. The infrastructure of the train—the tracks, signals, workers, tunnels and so on—enables the second twin to focus and develop thoughts away from the work being done to carry him. Hers is an experience of effort and his, ease.

Aerial photograph of Christchurch, 2013.Photograph by Becker Fraser Photography

The experience of each twin is defined by the length of their travel and the number of entities supporting them. The twin cutting her way through the jungle has few allies—she is part of a small gathering of objects. The twin on the train has a huge array of supporters and helpers that participate in an assemblage linking large parts of Europe together. Latour uses this story to argue that a different temporality, a different type of time is being brought into being in each case. For Latour, ‘time is not a general framework but a provisional result of the connection amongst entities.’5 In this way, time is produced or performed by different types of assemblages and networks. In relation to designed things, temporality is a consequence of the labour involved with coordinating objects into certain assemblages and arrangements.

It follows from this that a multiplicity of temporalities can be created by different kinds of material assemblages. The two most common types of time in architecture are temporary and permanent, but a closer look at a project like Agropolis (discussed later in this essay) offers a range of other typologies.

Performing Permanence

It is almost a cliché to state that one of the dominant characteristics of architecture is the quest for permanence. Architecture is meant to persist, to be durable. The term ‘permanent architecture’ does not exist because the idea of permanence is central to its logic.

Various authors have pointed out problems with the assumption of permanence. Mohsen Mostafavi and David Leatherbarrow state the obvious but often overlooked fact that ‘No building stands forever.’6 Even the greatest buildings and cities will one day fall into ruin, become redundant or be replaced. Mostafavi and Leatherbarrow identify a contradiction in which ‘buildings persist in time. Yet they do not.’7 The language we use to describe architecture often conceals the fact that nothing, in the end, lasts forever. In this sense, permanence is an imagined ideal that we collectively sustain.

Long lifespans are only achieved through the procedures of maintenance and care. Nigel Thrift writes that repair and maintenance are the ‘means by which the constant decay of the world is held off.’8 The deserted and vegetative town of Varosha on the island of Cyprus and the Demilitarised Zone between North and South Korea illustrate how so-called permanent objects quickly fail when no one is present to maintain them.9 The famous image of a decaying Villa Savoye evidences the tension between the essence of a finished work and the deleterious effects of time and weathering. Stewart Brand writes that ‘Architecture, we imagine, is permanent. And so our buildings thwart us.’10 The status of buildings as durable objects, like the twin’s travel on the train to Switzerland, is only sustained by an array of other devices and labour that continuously care and protect. The often overlooked labour of cleaning, repair and maintenance is the invisible work that creates the effect of permanence.

Permanent buildings are a result of large assemblages of different things working together to keep them standing: foundations, windows and ceilings make buildings stable and keep the weather outside; various institutions and organisations pay cleaners, caretakers and maintenance crews to maintain and repair its different parts; financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies provide capital to upgrade, rebuild and repair as time goes by. This creates a particular experience of use, and like the twin on the train, this enables other kinds of behaviour and activity to be focused on. Permanence is a kind of performance, but it is one we benefit from participating in. The permanence of architecture is a beneficial illusion that helps to sustain the institutions and organisations we want to have as stable markers of our society—courts, houses, great landmarks, universities, commercial centres, parliaments and civic spaces.

Performing Temporariness

What then of the temporary? Temporary architecture is a minor tradition that requires naming in a way that permanent architecture does not. Temporary projects have a beginning and an end. Permanent architecture is finished when it opens—this is its final state. A temporary project is finished when it disappears and ceases to be.

After the earthquakes in Christchurch, temporary projects proliferated with hundreds spreading across the damaged city. Agropolis was one such project initiated by Jessica Halliday, director of the Festival of Transitional Architecture (FESTA) and Bailey Perryman, a local food activist. It was developed as part of a larger collaboration that included local residents, businesses, chefs and artists. Launched at FESTA in 2013, the project was located on a vacant central site, one of thousands in the central city in which 80 percent of the area was demolished.

Agropolis consisted of around 12 large planter boxes, many of which were constructed from demolished houses, a large four-part composting facility and a tool shed made of earth. The project worked with local cafés to gather their green waste for composting and growing vegetables to sell back to the shops. Agropolis was temporary, it evolved at its first site over two years and then moved to another in 2015 before integrating with a larger urban farm project in 2016.

Authors of the 2012 book The Temporary City, Peter Bishop and Lesley Williams, define temporary projects in relation to intention.11 For them a project is temporary when the people that make and use it understand that it will not last. This kind of temporary use can be liberating: experiments and investigations can be made without the risk of permanent and expensive failure; different materials can be introduced and arranged into dynamic forms; members of the public and students can participate in the design and making of places with little fear of consequence; a larger and more radical variety of activities can be performed in public such as film screenings, bathing, dancing, shopping, eating and the growing of food. Examples of temporary projects internationally range from protests such as Occupy to community gardens and commercial pop-up spaces and are produced by a variety of designers, architects, retailers, activists, artists and community groups. Agropolis was an experiment in building systems of exchange and an alternative economy of food and waste based on freely given expertise and hundreds of volunteer hours.

Bringing things together—materials, organisations, people, practices—for a temporary period of time changes the relationship people have with the project or place. Experiences of provisionality, experimentation and uncertainty characterise temporary projects. Agropolis’ temporary condition produced a heightened sense of commitment and engagement. Bailey Perryman comments ‘You know every day of these projects is unique.”12

Agropolis during FESTA 2014Photograph by Annelies Zwaan

An important aspect of temporary projects is that the systems and assemblages required to bring them into being are often not as well integrated into the fabric of a place. Formal organisations such as councils and contractors, and integration with complex infrastructures of power, phone and water are frequently avoided by temporary projects, and instead ad hoc, improvised solutions are preferred. Often this means a more public display of making and developing projects and systems. In this way, the things involved with making, maintaining and unmaking of the projects are foregrounded. In contrast to more permanent architectures, in temporary projects such as Agropolis, maintenance and repair were public and visible activities, and through these different practices were brought to public view. In October 2013, Agropolis was launched with an event in the garden and the public was invited to help mix the mud for the earth shed with their feet. Many events, meetings, tours, festivals and working bees took place over its lifetime to sustain the farm and to offer people experiences and new knowledge about building and planting. These were experiences of a temporary project, but other forms of temporality were also being created and experienced at the same time.

Both permanent and temporary architecture can be framed as a performance of invisible and public entities working together to produce effects that are experienced by people. This framing suggests that different types of assembling and gathering may create other types of temporal experience.

Event Times

Event time is a sharp and focused form of temporality characterised by festivals and carnivals. In the 1970s and ‘80s, Bernard Tschumi argued that architecture can only be understood through the event, that space makes no sense without considering the things that happen within it.13 At its broadest, this argument arranges the programme and intent of the space as being a critical part of its imagining. In relation to the Agropolis project, festivals and events brought into the site include temporary restaurants, tours, talks, construction processes and installations.

Events often produce vibrant and surprising atmospheres and because each involves a unique gathering of people, weather and materials, the atmosphere cannot be repeated—they are experienced as unique and important. Projects become platforms for events that then offer one-off experiences, but the variability of the project’s parts—weather, furniture, different audiences—affects the degree to which the event is experienced as unique or one of a series.

Rhythms and Repetitions