Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

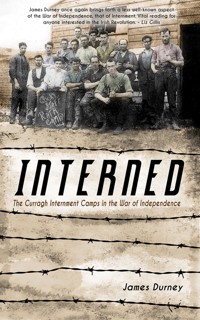

During the War of Independence, faced with an armed insurrection it couldn't stop, the British government introduced increasingly harsh penalties for suspected republicans, including internment without trial. This led to the incarceration of thousands of men in camps around the country, including the Rath and Hare Park Camps at the Curragh in County Kildare. Interned is the first book to tell the story of the men who were held in the Curragh internment camps, which housed republicans from all over Ireland. Faced with harsh conditions, unforgiving guards and inadequate and often inedible food, the prisoners maintained their defiance of the British regime and took whatever chances they could to defy their gaolers, including a number of escapes. The most audacious of these was in September 1921, during the Truce period, when sixty men escaped through a tunnel. This unique book is the first to investigate the Curragh Internment Camps, which housed thousands of republicans from all over Ireland. It contains a list of names and addresses of some 1,500 internees, which will be fascinating to their descendants and those interested in local history, as well as an exploration and details of the 1921 escape, which was one of the largest and most successful IRA escape in history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Website: www.jamesdurney.com

Twitter: @jamesmdurney

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© James Durney,, 2019

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 589 7

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

This book is dedicated to my grandson

Flynn James Reddy

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Internment

2 The Rath Camp

3 The Men Behind the Wire

4 ‘No Place Like Home’

5 Sport and Pastimes

6 Truce Outside, Dissent Inside

7 A Tunnel to freedom

8 The Foggy Dew

9 Prison breaks

10 Fé Ghlas ag Gallaibh – Locked up by Foreigners

11 And the Gates Flew Open

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

Appendix IV

Endnotes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

A big thanks to Mario Corrigan and Karel Kiely of the Local Studies and Genealogy Department, Newbridge Library, for all their help and for permission to use images from the Library Collection; thanks to Kevin Timmons for access to the autograph book of Jack Timmons; Michael Kenny for facilitating access to the autograph books and other ephemera held in the National Museum of Ireland (NMI); Sandra Heise, NMI, Collins Barracks, for access to the NMI collection; Diarmuid Bracken, Local Studies Section, Tullamore Library, Co. Offaly, for background information on Offaly internees and for facilitating contacts with local historians; Caitlin Browne, Local Studies Section, Roscommon Library, for background information on Roscommon internees; Maureen Costello, Local Studies Section, Mayo Library, for background information on Mayo internees; Aisling Mitchell, Local Studies Section, Galway Public Libraries, for background information on Galway internees; Aisling Doyle, Gaelic Athletic Association Museum, Croke Park, Dublin; Phillip McConway for his research and information on Offaly internees; Áine Delahunt for access to and use of her father’s autograph book from the Rath Camp; Fr Peter Clancy for access to and permission to use photographs from his collection; Jim Doyle, president of the 1916–21 Club, for permission to use his photograph of Fr Smith; Irish Life and Lore for the use of a photograph of Tom Byrne; Ronan Lee and John Stack for the information on Nellie Kearns; Brian McCabe, Kill Local History Group, for sourcing photos and a song from local internees; and Liz Gillis for her quote for the front cover.

Thanks also to my publisher, Mary Feehan, who has been supportive of this project from the start, and I thank the editorial staff at Mercier Press for their keen edits and comments.

Introduction

From 1916, faced with armed insurrection and revolutionary claims to democratic legitimacy, the British government responded with increasingly harsh emergency powers against Irish republicans. An important weapon in the government’s fight against republican violence was internment, or imprisonment, without trial. The purpose of this was to contain people believed by the British authorities to be a threat, without bringing charges against them, or having the intent to file any.1

It was in the immediate aftermath of Bloody Sunday, on 21 November 1920, that the British authorities decided to open internment camps in Ireland, facilitating a record use of imprisonment without trial. These camps, rather than established prisons, quickly became the largest holding centres of political prisoners. By late June 1921, 3,311 men were interned in the camps, constituting just over half of all those then incarcerated because of the War of Independence. As conditions in the country became more militarised, the circumstances of most imprisoned men came to appear similar to those of prisoners of war, a status the British authorities did not want to grant them. From the start of the conflict the British government had refused to concede that there was a war in Ireland, as claimed by Irish republicans, and by strengthening the police rather than the military it could justify the conflict as mere ‘civil disorder’. However, the opening of internment camps and the use of the military as guards helped to dispel this myth.

Despite the negative optics, internment was an easier option for the British than the long-drawn-out process of court-martialling republicans. In addition, republican prisoners had regularly demanded their transfer from convict prisons to special camps as part of their campaign for recognition as prisoners of war. Consequently, the British authorities believed that the camps would be more secure and that prisoners would be less trying, and more easily managed, if held in specially designed internment camps. However, Irish republicans in the Curragh internment camps proved enthusiastically that this was not to be.

1

Internment

The outbreak of war between Britain and Germany in August 1914 led to the enactment of the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, for the purposes of securing public safety in Britain and Ireland. The act, usually referred to as DORA, governed all citizens in Britain and Ireland during the years 1914–18. The legislation gave the government executive powers to suppress published criticism, control civilian behaviour, imprison without trial, and to commandeer economic resources for the war effort. DORA was amended and extended six times as the First World War progressed, and when war broke out in Ireland, with subsequent amendments, became the most relevant enactment for the suppression of political violence there.1

On the outbreak of the European war, the leaderships of the Irish Volunteers and the Ulster Volunteer Force pledged their support for the British war effort, mainly to strengthen their respective hands at the post-war bargaining table. The Irish Volunteers, however, split on this issue, and a minority group, heavily influenced by the secretive Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), began planning an insurrection to exploit Britain’s wartime difficulties.

At Easter 1916 this IRB-influenced group, together with the Irish Citizen Army, occupied positions in the centre of Dublin and declared an Irish Republic. The immediate British response was to issue two proclamations. One announced the imposition of martial law; the other, under Section 1 of the Defence of the Realm (Amendment) Act 1915, suspended the right to jury trial for breaches of the regulations, and thus created in Ireland an extensive court-martial jurisdiction.2

Militarily, the Rising was a failure. In the aftermath, a total of 3,340 men and seventy-nine women were taken prisoner or rounded up in countrywide raids. A lack of evidence against those arrested, however, meant that most of them were interned rather than prosecuted. But British intelligence had left much to be desired, as many of the prisoners were innocent, and 1,424 were released within a fortnight without charge.3 Fifteen of the prisoners were court-martialled and executed by firing squad during 3–12 May 1916. The rest were held under the Defence of the Realm Act 14B (internment without trial) and transferred to prisons in Britain.4

Twenty-five men arrested in Co. Kildare were initially held at Hare Park Camp, first built in 1915 to billet large numbers of troops training on the Curragh. The camp took its name from its location on the edge of the former Kildare Hunt Club Hare Park site. The Kildare prisoners were held at Hare Park until 8 May, when they were conveyed from the Curragh to Richmond Military Barracks in Dublin; from there they were subsequently deported to prisons in England.5 Their internment was short-lived, as most of the prisoners were released unconditionally in December 1916.

The Curragh Camp continued to be a place of detention for republicans as Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers reorganised in early 1917 and began to confront Britain’s Irish policy. When Thomas Ashe, the Easter Week hero of the Battle of Ashbourne, was arrested in Dublin in August 1917, having made what was termed a seditious speech in Ballinalee, Co. Longford, he was conveyed to the Curragh Camp and detained in the cells adjoining the guardroom at Keane Barracks. James Grehan, from Co. Laois, was arrested for illegal drilling and housed in a neighbouring cell. Michael Collins, then of the Irish National Aid Association, travelled from Dublin to the Curragh to visit both men – Collins was at that time a largely unknown entity to the British authorities. How it must have rankled with Dublin Castle some years later, when Collins had become such a thorn in their side, to know that he had visited the centre of the British military in Ireland.6

In the general election of December 1918, Sinn Féin successfully supplanted the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), winning seventy-three seats from a total of 105 and receiving 46.9 per cent of the vote island-wide. They quickly moved to set up an alternative parliament on 21 January 1919, known as Dáil Éireann – ‘National Assembly’ – and declare an Irish Republic.7 On the same day the Volunteers, now increasingly known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), began their military campaign against the crown forces with an attack on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in Soloheadbeg, Co. Tipperary, which left two policemen dead. Though it was not sanctioned by general headquarters (GHQ), this was the first deliberate killing of state security forces by the IRA.8

The escalation of the war from 1919 led to the strengthening of the Defence of the Realm Act, but the use of DORA legislation in response to the Irish conflict was nearing the end of its life, as the power to issue regulations was only exercisable ‘during the continuance of the present war’, meaning the First World War. It was a war emergency law that was meant to lapse at the end of hostilities in Europe. The old Crimes Act was used to create Special Military Areas, which allowed the authorities to control movement and ban public events, but without DORA it was impossible to continue interning republicans.9

In January 1920 a new internment policy was implemented, involving co-operation between the military and police. The British government put into effect a policy of moving prisoners to English jails to diminish any threat or influence they would have on the campaign in Ireland. On 5 April prisoners in Dublin’s Mountjoy Gaol began a mass hunger strike, demanding that DORA internees should be treated as political prisoners. Viscount French, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, said there would be no concessions to the prisoners, but the situation reached a crisis point with the resignation of the prison’s chief medical officer. The strikers turned down an offer of ‘ameliorative’ treatment; more men joined the strike bringing the number to ninety. A one-day labour strike added to the tension and distressing scenes were witnessed outside the prison as relatives and supporters awaited news. Dublin Castle then conceded the hunger strikers’ demand for political status, only to be presented promptly with a demand for their release; when liberation on parole was offered, the internees demanded unconditional release. On advice from the British government, the authorities in Mountjoy relented and transferred the hunger strikers en masse to hospitals for convalescence as a precursor to immediate release. The military programme of arrests since January, the impact of which had been growing steadily, was thrown into turmoil.10

New legislation was needed, and the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act (ROIA) was introduced on 9 August 1920 to deal with the rising republican violence and the collapse of the British civilian administration. (The army would pronounce ROIA procedures ‘too slow and cumbrous to be really effective against a whole population in rebellion’.) The act permitted the government to continue, under a new label, most of the restrictions imposed under DORA.11 In most cases this alteration was carried out by the substitution of the phrase ‘restoration or maintenance of order in Ireland’ for ‘the public safety or defence of the realm’.12 Consequently, DORA 14B, allowing internment without trial, became Restoration of Order in Ireland Regulation (ROIR) 14B.13

Over seventy regulations were made under the ROIA Act – civil law was practically revoked. Military and naval authorities were empowered to jail any Irish man or woman without charge or trial under Section 3 (6). Section 3 (1–5) provided for the replacement of trial by jury with courts martial in those areas where IRA activity was prevalent, and an extension of the jurisdiction of courts martial to include capital offences. In addition, military courts of inquiry were substituted for coroners’ inquests. This was mainly because (up to August 1920) thirty-three coroners’ inquests had indicted military or police personnel for murder. In addition, the regulations provided for the withholding of grants, otherwise payable from public funds, from local authorities that refused to discharge statutory obligations.14

However, the introduction of ROIA was followed by a general increase in IRA activities, which culminated in the shooting dead of twelve British intelligence agents on 21 November 1920 in Dublin. The immediate British response was to resort to internment on an unprecedented scale and an overall intensification of the counter-insurgency drive, with full use made of the new regulations. On 22 November orders were given to ‘arrest all leaders of the IRA and other “wanted men” and to intern them, should conviction for offences be unobtainable in Ireland’. From that point, if there was not enough evidence to secure a conviction, the military authority was assigned to forward the names of known republicans for internment.15

‘The great round-up,’ the Irish Independent reported, ‘of prominent Sinn Feiners and public men in the provinces within the last few days appears to have been on a larger scale than that after the 1916 insurrection. The hundreds of arrests which have taken place do not appear to have been the result of anything found on the premises of the men, as in many cases the men were asked for and no search was made.’16

In the two weeks following Bloody Sunday, 500 internment orders were made and hundreds of men rounded up. According to TheFreeman’s Journal, a ‘high authority’ source said: ‘We are going over Ireland with a fine-comb.’ The new internees were to be held in internment camps ‘until such time as they can be safely tried’.17

The Donegal News of 4 December said: ‘At the present moment there are close on seventeen hundred Irishmen locked up in British jails, and the present intention is to round up something like five thousand. Preparations have been made for the reception of that number, and it is the belief of [Sir Hamar] Greenwood and his advisers that when five thousand Irishmen are in prison, the Sinn Fein movement will be effectively smashed.’

Temporary internment camps were hastily opened at Dollymount, on the north coast of Dublin Bay, and Collinstown, in north Co. Dublin, where the British Army had established a training camp and an airfield during the First World War. Meanwhile, a permanent camp was being prepared at Ballykinlar, on Dundrum Bay in Co. Down.18The former British military training camp there had been identified as the most appropriate location for this and thus became the first mass internment camp in Ireland when it opened in early December 1920 to receive its first batch of prisoners from Arbour Hill Prison in Dublin.19

There were two internment camps at Ballykinlar, usually distinguished as Camp I and Camp II. Though these two camps adjoined each other for a short distance at one end, being separated only by the double fence of barbed wire that surrounded each camp, they were isolated from each other, and communication between the prisoners in one camp and those in the other was forbidden. Three sides of the camp were surrounded by the sea, which simplified the problem of guarding the prisoners. Each camp held (when full) 1,000 prisoners. These were divided, for purposes of administration, into four companies (250 men in each), and each company was housed in ten huts (twenty-five men to each hut). In addition to the huts in which the men slept, the camp buildings included large central huts for use as a chapel, dining hall, recreation area (for concerts, etc.), canteen, cookhouse and workshops.20

On 27 November a Belfast Newsletter correspondent wrote: ‘The internment indicates the acceptance in a certain sense of the Republican Army’s declaration of a state of war and their demand for treatment as prisoners of war.’ The Belfast Telegraph concurred: ‘Men will be liable to be interned without trial, and membership of the Irish Republican Army will be sufficient reason for this treatment.’21

The British system of internment against Irish republicans was described as follows:

[Army] Divisions submitted to GHQ lists of men they wished to intern, giving their believed rank in the IRA. These lists were examined at GHQ and forwarded to the Chief Secretary with application for internment warrants. Owing to delay in the issue of warrants and the congestion which would have occurred in divisional areas had the arrested men been retained until the warrants were received, divisions were authorised to ship to Ballykinlar batches of men whose internment had been approved, as and when shipping facilities became available, the internment warrants were then sent direct from GHQ to the Commandant of the internment camp.22

The main difficulty experienced was found to be one of identity, and in many cases the civilian authorities did not know enough about the suspect to put the correct name on the requisite form, so the military authorities sometimes had trouble in fitting the warrants to the individuals arrested. Many men were interned wrongfully, while others were interned under an incorrect name. The military authorities insisted on attributing an IRA rank to all of those interned – though they were not as successful as they believed in doing this and gave officer ranks to many who were not. Likewise, members of the British government were keen to claim that all the internees were ‘believed to be active members of the Irish Republican Army’.23

Internment powers continued to be used on a massive scale as the War of Independence entered the new and most crucial year of 1921. According to Dublin Castle, by the last week of December 1920, 995 internment orders had been issued and 800 men interned at Ballykinlar, which at that time only had a capacity of 1,000.24 By 17 January 1921 the number of internees had risen to 1,478 and, with no let-up in arrests, additional internment places had to be established.25In January 1921 an internment camp was opened at the former military installation at Bere Island in Co. Cork.26 The following month another camp was opened at Fort Westmoreland, the military fortress on Spike Island in Cork Harbour, which before 1885 had been the chief depot for Irish convicts. It was expected to accommodate 500 men and, because of its location, was believed to be escape-proof.27

In the week ending 21 February 1921 a further 507 men had been arrested, bringing the total number of internees to 1,985.28 Greater capacity was required to deal with this growing number of detainees. To supplement this, another internment camp was constructed on the Curragh plains some 400 metres north-west of the Gibbet Rath to house about 1,300 men. Known as the Rath Camp, it took its name from the historic Gibbet Rath – a large Viking-era enclosure which was also the scene of a massacre of rebels during the 1798 rebellion.29 On 12 March 1921 the Leinster Leader reported: ‘Another internment camp, conducted on the same lines as the Ballykinlar Camp, has been opened at the Rath, Curragh. A large number of prisoners have been transferred from the Hare Park Camp to the Rath, where no visits are allowed.’30

2

The Rath Camp

In the first three months of 1921 crown forces arrested a considerable number of republicans. Numbers interned rose from 1,478 for the week ending 17 January, to 2,569 for the week ending 21 March.1 The internment camp at Ballykinlar had reached its capacity and instructions were received from British GHQ to prepare a further internment camp at the Curragh military base in Co. Kildare for the reception of internees from the British 5th Division and the Dublin District Division areas.2

Located about 3 miles from the garrison town of Newbridge, the Curragh is a natural, grassy, treeless plain of about 4,658 acres. It is not a flat tract of land, but has a series of hills and hollows, and in parts is studded with gorse bushes. At one time the Curragh was a sheet of water, hence its sandy and uneven soil. From east to west it measures about 5 miles in length and it is 2 miles in breadth. The adjacent racecourse has been in operation since 1741.3

The Curragh plain has been the site of military activity from prehistoric times and was the scene of the worst atrocity of the 1798 Rebellion. On 29 May 1798 a force of about 400 rebels, pursuant to an agreement made between them and General Ralph Dundas, the officer commanding the British forces in the midlands, had gathered at the Gibbet Rath to lay down their arms. By this stage the rebellion in Co. Kildare was practically over. Patrick O’Kelly, one of the rebel leaders, wrote that, once their arms had been dumped, the rebels were forced to kneel and beg the king’s pardon. The British commander at the scene, Major General Sir James Duff, said in a letter to Lieutenant General Lake that he was ‘determined to make a dreadful example of the rebels’. He ordered his men to ‘charge and spare no rebel’. Duff attempted to justify the actions of his men:

Kildare two o’clock p.m. – We found the rebels retiring from the town on our arrival, armed. We followed them with the dragoons. I sent some of the yeomen to tell them, on laying down their arms, they should not be hurt. Unfortunately, some of them fired on the troops; but from that moment they were attacked on all sides – nothing could stop the rage of the troops. I believe from two to three hundred of the rebels were killed. We have three men killed and several wounded.4

An estimated 350 rebels were killed at Gibbet Rath, most of them trying to escape the armed yeomen and dragoons.5Gibbet Rath became a byword for British duplicity and another massacre in a long litany of crown force atrocities, so it was an appropriate place to house the rebels of another generation.

The significance of the position of the Rath Camp was not lost on its occupants. Micheál Ó Laoghaire wrote in his witness statement: ‘Interned in the vicinity of such a sacred place with our martyred dead sleeping beside us should, to my mind, be an inspiration to us as I am sure their proud spirits hovered within and around our Camp, watching over us and praying for our liberation as well as the freedom of Ireland.’6

As a result of Britain’s involvement in the Crimean War (fought from October 1853 to February 1856, in which an alliance comprising Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia defeated the Russian Empire), the Inspector General of Fortifications, Sir John F. Burgoyne, issued instructions in 1855 that a temporary camp for 10,000 infantry be built on the Curragh to train for action in the Crimea.7 Subsequently, the camp became permanent and included both a Catholic and an Anglican church, a school and a post office. The Curragh Camp was used to train troops for both the regular and the reserve of the British Army in various duties for overseas service. During the First World War the camp was a great centre of military activity.

When the Easter Rising broke out in 1916, the 3rd Reserve Cavalry Brigade at the Curragh was in Dublin within five hours. According to Augustine Birrell, the chief secretary of Ireland, ‘the rebellion failed from the beginning, because the soldiers were there before the end of the [first] day in quite sufficient force from the Curragh and Belfast’.8 And while British troops, many of them Irish-born, were leaving the Curragh for Dublin, others were preparing the huts at Hare Park Camp for an influx of men arrested in the wake of the Rising. Consequently, the first use of the Curragh Camp for detainees was for the twenty-five men from Co. Kildare who were arrested during and after the Rising and held in the camp before being sent to Dublin for processing, sentencing and deportation to prisons in England.9

In March 1920 an auxiliary police depot was established at Hare Park Camp to train British recruits to the RIC. Hundreds of recruits, known as ‘Black and Tans’, received a six-week police training course at Hare Park before a dedicated training centre was established at Beggars Bush Barracks in Dublin.10 Following this, Hare Park was once again adapted to accommodate republican prisoners.

By mid-February 1921 there were forty-nine men interned there, among them Fr Smith, the Catholic curate (CC) of Rahan, Co. Offaly, who played a prominent part in religious ministering to the internees. The four huts at Hare Park could accommodate twenty-eight men each. Bedding consisted of a mattress, pillow and three blankets. A week later it was deemed to be ‘full’, with 149 prisoners. To supplement it, construction began on what was to become the Rath Camp, around 450 yards to the east.11

The huts in Hare Park were open from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., although one report said the prisoners were locked up after the 6.30 parade in the evening. Visits were allowed and visiting times for family and friends were Mondays and Fridays from 11.30 a.m. to 12.30 p.m.12Edith Garland, a Cumann na mBan member from Newbridge, Co. Kildare, was a regular visitor and rarely missed visiting day. She moved among the prisoners with a cheery word, a message from outside friends or a smuggled note, and always with a parcel of good provisions to supplement the prison food.13

At the time, the British Army in Ireland was in the throes of demobilisation and reorganisation on a peace footing. Ireland was grouped into three divisions – the Northern, the Midland and Connaught, and the Southern. In the autumn a fresh sub-division was made creating four districts – the Dublin, Northern, Midland, and Southern divisions, with the Midland district extending westward to include the Connaught sub-district. The army’s 5th Division, under the command of Major General Sir Hugh Sandham Jeudwine, with headquarters at the Curragh Camp, was responsible for the Midland (excluding the Connaught sub-district), Dublin and Northern districts. Brigadier General Percy Cyriac Burrell Skinner, commanding the Curragh Brigade and area, was, by virtue of his seniority, officer commanding (OC) the Curragh garrison.14 He was responsible for the implementation of the new internment camp at the Curragh. Troops from the 5th Division made up the camp guards.

The Rath Internment Camp was designed to hold 1,000 prisoners and was laid out on the southern fringe of the Curragh Camp directly opposite the grandstand of the racecourse. It consisted of about 10 acres of the Curragh plain enclosed in a rectangle of barbed-wire entanglements. There were two fences encircling the camp, each 10 feet high and 4 feet wide. Between the fences was a 20-foot-wide corridor patrolled by sentries, which the prisoners called ‘No Man’s Land’. At each corner of the compound stood high blockhouses from which powerful searchlights lit up the centre passage and played on the huts. Sentries armed with rifles and machine guns manned these watchtowers twenty-four hours a day, calling out ‘All is well’ on the stroke of the hour throughout the night. No. 1 post would begin: ‘No. 1 post and all is well.’ No. 2 would repeat this for their post, and Nos 3 and 4 would follow suit. This ‘All is well’ continued through the night, every night.

Inside the rectangular enclosure there were some fifty to sixty wooden huts (20 feet by 60 feet), which served as sleeping quarters, and huts used for a hospital, a canteen (dining hall), a cookhouse, a chapel and a library. There was also a hut used for British military stores, and a sports ground large enough to provide a football pitch and space for exercise. The wooden huts were arranged in four symmetrical rows, referred to as ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ lines.

Beyond the main barrier, the camp was surrounded by a further fence consisting of five single strands of barbed wire about 4 feet high, not designed to keep the prisoners in, but rather to prevent animals approaching the main enclosure. Nevertheless, it was a further obstacle to the possibility of escape. The Rath Camp was regarded as escape-proof. To add to the difficulties of intending escapers, a large searchlight was mounted on the watchtower of the main military camp. During the hours of darkness, the beam from the searchlight lit up the entire Curragh plain.15

The construction of the camp by the Royal Engineers took a great deal of time and labour as the engineers were concerned with making the camp secure. On the other hand, the huts had previously been used as an emergency camp and were hastily erected and hastily evacuated, so when the internees arrived the accommodation was not in good condition. The roofs were leaking, the floors draughty, the surroundings, especially in wet weather, sodden, and the so-called roads rough and overgrown with weeds. Although the capacity of the camp was for a wartime battalion of about 1,000 men, when it was eventually filled with internees there were around 1,300 men, which led to overcrowding.16

By the beginning of March 1921 the camp was ready for business. The Leinster Leader, a weekly newspaper published in Naas, carried a report in its 12 March issue that ‘another internment camp, conducted on the same lines as the Ballykinlar Camp, has been opened at the Rath, Curragh.’ The newspaper went on to report that fifty prisoners from the west, including a priest, passed through Naas on their way to the Curragh, and thirty prisoners from Athlone Military Barracks were transferred to the Rath Camp, along with a further seventeen prisoners from Maryborough Gaol.17 The editor of the Leinster Leader at that time was Michael O’Kelly, who had been arrested and held at Hare Park during Easter Week. Within a few months O’Kelly had joined his comrades at the Rath Camp.

Notices were posted in national newspapers that parcels for prisoners at the camp should be carefully packed in wooden boxes or canvas and strong brown paper. The list of contents and address were to be enclosed in the parcel, and all parcels were to be plainly addressed, both on the cover and on a tie-on label. The observance of these rules, the notice said, would facilitate the delivery of parcels without delay or loss. Parcels contained a variety of tinned goods, home-made cakes, cigarettes, clothing and playing cards. Such parcels arrived in the camp quite regularly and in good condition. They made life a little more bearable and gave prisoners goods to barter with each other. Letters from home were also received regularly; prisoners could send out one letter per week.18

One of the first republican prisoners to arrive at the Rath Camp was Joseph Lawless:

It must have been about the first or second week of March 1921 that we were moved from Arbour Hill to the Curragh. Looking up some old letters of mine … I found one which seemed to have been written from the Rath Camp immediately, or within a day or [so] of my arrival there. This was dated 3rd March 1921 and so established the approximate date of our arrival, which I had thought to be about a month later.

We were paraded that morning in the main hall of Arbour Hill Prison and a list of about a hundred and fifty names called out, which represented more than half of the prisoners left in the prison at the time. The Governor then read to us the terms of our internment order and we were informed that the place of our internment was to be the Rath Camp on the Curragh of Kildare. Through the narrow iron gate covering the doorway of the prison we could catch a glimpse of the awaiting escort and hear the buzz of their vehicles as they pulled into position near the entrance …

Any ideas of escape en route were quickly dissipated as we were lined up on the roadway outside the prison and the line of lorries for our conveyance pulled up to where we stood on the footpath. The escort consisted of a full company of troops, a platoon in front, a platoon in rear, and the remaining platoons divided amongst the lorries on which we were to travel. In addition to this there was an armoured car in front of the convoy as well as one in rear, and a couple of tender-loads of Auxiliaries cruised around the convoy until we were clear of the environs of the city. From there on to the Curragh an aeroplane from the military aerodrome at Baldonnell flew in circles above us keeping watch for any possible attempt at rescue. When we entered upon the Curragh Plain, near Ballymany crossroads, the aeroplane landed ahead of us and, the convoy being halted, we watched the pilot coming across to have his duty order signed by the officer commanding the convoy.

… People who have lived their lives in more or less enclosed places, particularly in cities, are, I think, bound to get a certain agraphobic [sic] feeling of isolation when they first find themselves in a wide open space unbounded by walls, hedges or fences of any kind. But I had also another feeling, induced by the view of the barracks and the other military establishments set upon the ridge in the middle of the plain. Here seemed to be the unassailable heart of the powerful enemy of our nation. Here were military forces in strength, and from where they could sally forth at will to crush the puny efforts of the native people.

I did not at the time, of course, arrange my thoughts as I have written them here, but this represents the feelings we had and explains why there was little conversation between us as we were driven through the Curragh Camp, past Harepark [sic] Camp and halted at last, to dismount outside the newly erected internment camp just west of the Gibbet Rath.19

A hut that acted as a guardroom, manned by a military guard, stood near the entrance gate between the barbed wire and the road. The remainder of the troops engaged in the guarding and administration of the camp were quartered in a hutment camp about 200 yards on the south side of the internment camp. The guard was provided by the 2nd Battalion, the Suffolk Regiment, of which headquarters and two companies had been moved from Boyle, Co. Roscommon, at the end of February. According to the official history of the 5th Division, the first internees arrived on 2 March.20Lawless, who had been appointed vice-commandant of the republican prisoners, wrote:

I think we were the first batch of prisoners to arrive at the new camp, the construction of which was not quite finished when we arrived. It is possible that some few may have arrived before us on the same day or the day before, but my recollection is that we went into occupation on the first line of huts and began immediately to elect our own commandant and administrative officers. Peadar McMahon became the prisoners’ commandant and I his vice-commandant … We thought it peculiar when we first arrived that we were urged by the military authorities to proceed immediately with the election of leaders, and when this had been done, to find that they were so solicitous as to provide specially arranged quarters for the prisoners’ commandant and his staff. They refused, however, to recognise our military titles as commandant and vice-commandant and insisted upon addressing us and referring to us at all times as ‘Internee Supervisor’ and ‘Assistant Internee Supervisor’.21

The British commandant of the internment camp was Colonel John Connor Hanna, Royal Artillery, who joined the British Army in 1892, was mentioned twice in dispatches and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and the French Croix de Guerre (War Cross) during the First World War. He was born in Madras, India, in 1871, the eldest son of Francis B. Hanna, an engineer, and Elizabeth Connor of Kilcoole, Co. Wicklow.22

Hanna’s aide-de-camp, or adjutant, was Lieutenant Hubert Frederick Vinden, 2nd Suffolk Regiment, who had served as an officer on the Western Front during 1915–17, taking part in the Battle of the Somme (1916) and the Battle of Arras (1917). He arrived in Ireland with his battalion in January 1921 and, after a few weeks in Boyle, they were detailed to the Curragh Camp. He said, ‘I thought this was a happy choice, as our senior officers who had been “inside” in Germany should know the ropes of guard duties and the wiles of prisoners trying to escape.’ However, the military quickly found that the staffing of the camps was a considerable drain on manpower and morale. Lieutenant Vinden soon felt he was too inexperienced for the job and described the shortcomings of guard duty for regular soldiers:

Aid to the civil power is one of the most unpleasant tasks which can fall to soldiers, and our colonel, Arthur Peeples, was most alert to the pitfalls for the military. If anything went wrong, it would be blamed on the soldiers and officers … Colonel Peeples wanted to avoid being in command of the regiment and at the same time be in charge of the internment camp, while the regiment only provided the guards required for it. He appointed me to be staff captain to the commandant and this brought me in a very welcome extra five shillings a day.23

The internees appointed their own OC as well as a camp council to run all their affairs in the camp. Captain Micheál Ó Laoghaire, OC Liverpool Company, Irish Volunteers, said:

When we arrived in the Camp, A Line was only full [sic] but, from that day on, prisoners began to arrive daily from Dublin, Tullamore, Galway, Mayo, Sligo, Roscommon, Leitrim, Kildare, Meath and Wicklow, with the result that the Camp that looked to us on our arrival as derelict and desolate in a few weeks became a hive of living men.

Then the work of re-organisation had to begin. We were lucky in this respect for we had in the Camp several prominent I.R.A. men who knew each other and there was not much difficulty in renewing comradeship and fidelity. Volunteer officers from their own particular areas would vouch for their Volunteers and so, in a short time, we had a good idea of who was who.

The next important step was the election of officers. A meeting of hut leaders was held and the following officers were elected:

Camp Commandant – Peadar McMahon

Vice Camp Commandant – Joe Lawless

Camp Quartermaster – Micheál Ó Laoghaire (myself)

Line Officers – Mick McHugh A Line,

Tom Derrig B Line,

late James Victory C Line,

Joe Vize D Line

A medical officer was appointed in charge of the hospital. The first man appointed was the late Dr. O’Higgins of Stradbally (father of the late Kevin O’Higgins) who was afterwards released. Dr. O’Higgins was Coroner for Leix at the time and was very prominent and well respected. The authorities offered him his release if he would undertake to sign a bond for £200 (or £300) which the doctor refused to do. They approached him again a short time afterwards and reduced the bond. He not only refused but told them, with all the indignation at his disposal, that if they did not release him unconditionally his bones would rot in the Camp compound before he would sign any undertaking. A week later he was released unconditionally. Dr. Brian Cusack was appointed M.O. [Medical Officer] and Dr. Fehily [sic] Assistant M.O. (both prisoners).

… The actual management of the Camp, including the hospital, was now handed over to us. A medical Corporal and Orderly (British soldiers) were the only two soldiers who slept inside the Camp. The British M.O. called in daily. The work was carried out by our own medical men and students under whose care patients were tended and treated.

I took over the food stores from Lieutenant Mallett, British Camp Quartermaster, including weighing-scales, tables and butcher’s knives.24

The reason the doctor and others refused to sign a bond for their release was because this only allowed for a conditional release, in which the signee could be rearrested if deemed to be once again involved in republican activities. The prisoners refused to accept anything but an unconditional release.

The internees were treated like prisoners of war but were not recognised as ‘belligerents’, as this would have afforded them, and the republican movement, a recognition the British authorities were not willing to concede. Nevertheless, the internees were given great leeway in organising their own lives. Line captains reported all grievances to the internees’ OC, who in turn placed them before the British OC. The military supplied the food, but the internees had their own cooking staff. Roll call took place each morning and evening, and a general inspection at midday.

Collinstown Camp and prisons such as Arbour Hill were used as clearing stations for prisoners until a consignment was ready for dispatch to Rath or Ballykinlar. Dr Brian A. Cusack was a medical doctor from Oldtown in north County Dublin, who moved to Galway where he became involved in the IRB. He was a sitting Teachta Dála (TD) for North Galway when he was arrested and taken to Collinstown and subsequently Arbour Hill:

One day in Arbour Hill one of the Military Police put his hand on my shoulder. I objected to this and I told him so in no uncertain manner. I was taken before the Governor and the next day I was transferred to the Curragh. This was a welcome change as in Arbour Hill we were three to a cell and in the Curragh we had plenty of open air and better conditions. I was kept in internment until after the Truce was signed.

There were a number of doctors in the internment camp in the Curragh as prisoners. A British Medical Officer – an Irishman and a very capable man [–] visited the Camp one day and asked me if I would take charge of all medical institutions within the Camp. I agreed to do so under certain conditions, the principal one of which was that all our sick prisoners be sent for treatment to 3 Dublin Hospitals. He said ‘We cannot do that’. However, he really did all he could to facilitate us.25

As more men arrived, there was a pressing need for organisation, and the camp leadership soon took over these responsibilities. Tom Byrne, a Boer War and Easter Week veteran, wrote:

We ran the camp ourselves, making our own paths out of concrete blocks. In other ways, too, we were allowed within limits to improve our housing conditions. But such concessions were purely domestic and there was no leniency in the manner in which we were guarded for our jailers were constantly on the watch to offset attempts at escape. To try and catch us out there would be sudden swoops on the huts with intensive searches and the barbed wire was being constantly strengthened.26

The routine of the camp was dictated by two disciplinary systems. On the one hand, the British regulations set the times when the internees were locked up and let out, the number of letters they might write and the amount of food provided. But the internees also had their own disciplinary system, imposed from the beginning. Micheál Ó Laoghaire said:

The first essential was the appointment of reliable Hut Leaders who were known and trusted. In this connection, so far as I know and remember, all the hut leaders were trusted men and carried out carefully the duties assigned to them. There were about thirty men in each hut under the charge of the hut leader whom they appointed themselves. His duties openly were to maintain law and order in the hut, detail men for duty and keep a watching brief over them, always reporting anything he thought important, at the same time becoming acquainted with his men and ascertaining, if possible, the views of every man in the hut. His fellow-Volunteers he coached on those lines also. In this way, he was soon able to give an account of each man in the hut. This, of course, only referred to men who were not known to any Volunteer in the Camp. When his suspicions were aroused, he kept the suspects, naturally unknown to themselves, under observation and their correspondence was seized in our own post office and examined. From information like this, we were able to associate directly or indirectly 28 prisoners. When some of them were openly accused, they fled from the Camp under the protection of the military. This was the work of our Intelligence men and they usually held their meetings in my stores.