11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This revised introduction to Britain in the first millennium BC incorporates modifications to a story that is still controversial. It covers a time of dramatic change in Europe, dominated by the emergence of Rome as a megastate. In Britain, on the extremity of these developments, it was a period of profound social and economic change, which saw the end of the prehistoric cycle of the Neolithic and bronze Ages, and the beginning of a world that was to change little in its essentials until the great voyages of colonization and trade of the 16th century. The theme of the book is that of social change within an insular society sitting on the periphery of a world in revolution.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 258

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

More about Batsford

Founded in 1843, Batsford is an imprint with an illustrious heritage that has built a tradition of excellence over the last 168 years. Batsford has developed an enviable reputation in the areas of fashion and design, embroidery and textiles, chess, heritage, horticulture and architecture.

First Published 1995

This edition published 2004 by Batsford,

an imprint of Pavilion Books Company Limited

1 Gower Street

London

WC1E 6HD

www.batsford.com

Twitter: @Batsford_Books

Copyright © Barry Cunliffe 1995, 2004

The right of Barry Cunliffe to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, displayed, extracted, reproduced, utilised, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise including but not limited to photocopying, recording, or scanning without the prior written permission of the Pavilion Books Company Limited.

First eBook publication 2014

ISBN 978-1-84994-240-9

Also available in paperback

ISBN 978-0713488395

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to record my thanks to Peter Kemmis Betty and Stephen Johnson who invited me to write this book, thus bringing upon themselves the task of reading the first draft of the manuscript. Their helpful criticisms were gratefully received and acted upon resulting in a text which is crisper and more jargon-free than it would otherwise have been.

In preparing the book I have benefited very considerably from the help of my colleagues at the Institute of Archaeology at Oxford: Lynda Smithson translated my increasingly illegible scribble into an immaculate typescript; Alison Wilkins prepared all the line drawings which are not otherwise credited; while Bob Wilkins and Jennie Lowe produced prints of photographs from the Institute’s archives (22, 46, 47, 48, 62, 63, 65, 66, 71, 75, 86, 92, 94, 98, 108). Edward Impey, advised by Sonia Hawkes, drew the reconstruction of the Cow Down House (26).

All other photographs were provided as follows:

Fig 1, 29, 49 Copyright reserved Cambridge University Collection of Air Photographs

Fig 4, 6, 16, 24, 46, 50, 58, 103 © Crown Copyright NMR

Fig 5, 31, 32 Steve Hartgroves, Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council

Fig 7, 8, 40, 69, 77, 78, 81, 87, 88, 89, 97, 109 © Copyright The British Museum

Fig 9 Hampshire County Council Museums & Archives Service

Fig 10 Bill Marsden

Fig 11, 12, 80, 82, 84 National Museums of Scotland

Fig 13, 51, 53, 54, 74 Crown Copyright reproduced Courtesy of Historic Scotland

Fig 23, 45 © Crown Copyright RCAHMW

Fig 33, 90, 104 © Copyright English Heritage Photo Library

Fig 56 © Doe Collection/ English Heritage Photo Library

Fig 95, 101 Barry Cunliffe

Fig 99 Winchester Archaeology Unit

Fig 105 Department of the Environment Photograph Library

Fig 106 Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology (No 1883.766)

Fig 107 Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology (No 1948.1186)

Picture Research by Sandra Schneider

CONTENTS

PREFACE

1 THE LAND

2 THE PEOPLE: RACE, LANGUAGE AND POPULATION

3 THE GREAT TRANSITION: TAMING THE LAND

4 CONFLICTING CLAIMS: THE EMERGENCE OF TRIBAL ENTITIES

5 RE-FORMATION AND TRIBAL SOCIETY: 150 BC – AD 43

6 OF CHIEFS AND KINGS

7 WAR MAD BUT NOT OF EVIL CHARACTER

8 APPROACHING THE GODS

9 THE IRON AGE ACHIEVEMENT: A LONGER PERSPECTIVE

PLACES TO VISIT

FURTHER READING

INDEX

PREFACE

I was asked to write this book at the time when I was just completing the third edition of Iron Age Communities in Britain. My immediate reaction was to say no but after a while I found myself thinking more and more about the attraction of writing an interpretative essay freed from the need to assemble and assess the huge quantity of data which formed the necessary basis of the textbook. The attraction soon became a compulsion: what follows is the result.

The format of this series imposes a welcome and creative constraint. In an essay of 40,000 words it is necessary to be highly selective and to rise above the disparate mass of evidence in order to discover the patterns and perspectives inherent, but often obscured, within it. From such a viewpoint it becomes increasingly obvious that the development of Britain cannot begin to be understood in isolation – the communities of these islands are, and always have been, part of a much broader European system. It is for this reason that, from time to time, we pause, in this book, to view the wider European scene.

Yet it would be quite wrong to imply that the development of British society was controlled from outside. Far from it. As we will see, the varied landscapes of these islands encouraged social diversity: they provided constraints to which communities responded with fascinating originality. The story of British society must always be structured around the framework of the land but often the catalyst for change is external.

The first millennium BC was a time of dramatic change in Europe, dominated by the emergence of Rome as a megastate. In Britain, on the very extremity of these developments, it was a time of huge social and economic change which saw the ending of the prehistoric cycle of the Neolithic and Bronze Age and the beginning of a world which, in all its essentials, was to change little until the oceans were conquered in the sixteenth century.

Our theme then is of social change within an insular society sitting on the periphery of a world in revolution. It is an epic well worth the telling.

The opportunity to produce this second edition came ten years later. The original text has been retained as far as possible but a number of new illustrations have been introduced.

Barry Cunliffe

Oxford, January 2003

1THE LAND

It is a common misapprehension that because Britain is an island it was cut off from the Continent, its communities developing in grand isolation, only occasionally being jolted from their comfortable complacency by incoming bands of warriors prepared to brave the dangers of the Channel and the North Sea. Throughout prehistory the reality was, in all probability, very different. The concept of ‘our island fortress’ is a political construct of the modern world, born with the threat of the Spanish Armada and encouraged from time to time thereafter when Continentals like Napoleon and Hitler cast covetous eyes across the Channel. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars could back-project this model, pointing to the invasions of the Normans, the Vikings, the Saxons and the Romans, and concluding that thus it had always been. Such generalizations may be helpful at one level but at another they can be very misleading. The conquests and folk movements of the first millennium AD were characteristic of the phase of European history dominated by the rise and fall of the megastate of Rome. Before that, in the first and second millennia bc, the dynamics of European society were very different. This is not to say that there were no folk movements and aggressive onslaughts but simply that the scale was in an altogether different register.

Another preconception that we need to rid ourselves of at the outset is our modern sense of cognitive geography. We are used to seeing Britain neatly and accurately depicted on a map separated by sea from the Continent and with its major lines of communication focusing on London. The vision is one of inward-looking insularity and our experiences tend to reinforce this. Leaving Oxford early one morning and travelling by coach, aeroplane, hire car and boat I was able to explore the broch of Mousa in the Shetland Isles by late afternoon. On another occasion, again leaving Oxford, it took only an hour and a half to reach Portsmouth and then an interminable nine hours at sea before arriving at the coast of Brittany. Experiences of this kind condition our attitudes to geography. But the availability of maps and improved communications are a recent phenomenon. That there may be other visions of geography was vividly brought home to me in Orkney in the mid-1970s, when I was standing on the harbourside at Kirkwall talking to a local farmer about the autumn export of cattle. When asked where his cattle went for sale and slaughter he said that they were sent south. Pressed as to where, he said ‘far south ... to Aberdeen, and sometimes much further – to the English plain beyond’. His cognitive geography was not one conditioned by maps and air travel but was informed by his own observations and conversations on the quayside.

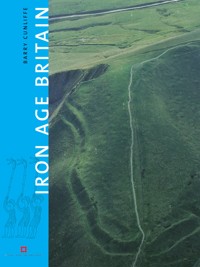

1 The rocky promontories of south-western Britain, here Treryn Dinas, St Levan, are closely comparable to those of Armorica and Galicia. These regions were bound together by complex networks of trade and exchange operating along the Atlantic sea routes.

Let us then put aside our modern preconceptions and think of the past. The vast bulk of the population of the English Midlands in the early Middle Ages are unlikely to have travelled more than 30–50 km (20 or 30 miles) from their homes. Their horizons were strictly limited and access to information restricted in the extreme. Yet a man of Winchelsea or Rye was in an entirely different position. He may not himself have ventured far but on the quays he would have heard talk of a wider world and in the taverns may well have drunk Gascon wine poured from elegant Santonge pitchers. His vision of the world would have been different. For him to travel to Oxford to visit the Benedictine House would have meant a far longer and more arduous journey than a visit to the Brothers’ monastery at Fécamp. Much the same may well have been true in the first millennium bc when mobility by land is likely to have been even more restricted.

The most helpful way to visualize the all-important question of mobility and information exchange is to accept that while the sea can link, the land can divide. Thus Britain might better be considered not as an entity but as a series of zones defined in terms of their degree of relationship to the Continent. Using this approach we can recognize three zones of contact. The most obvious is that linked by the Straits of Dover enabling the communities of south-east Britain, occupying the littoral between Newhaven and North Foreland, to maintain easy contact with the French coast from Calais to Le Havre and by means of the Seine and the Somme to much of the French hinterland.

2 The British Isles has always been closely linked to Continental Europe. The map summarizes the principal axes of contact in the first millenniumBC.

The southern extremity of the North Sea constitutes another zone of contact, putting the river systems of eastern England, from the Thames to the Yare, within easy reach of the rivers of the Low Countries. Distances are not great: the direct route between Holland and Norfolk is barely 170 km (106 miles).

The west provides a more complex picture. Here peninsulas of old hard rock thrust into the Atlantic – Holyhead, St David’s Head, Land’s End, Finistère and Finisterre (1). They are all, to their inhabitants, the ends of the world but the seas between linked them, providing a web of ancient routes along which sailors could carry commodities and ideas, plying the coasts and seas they knew, and in the ports interacting with others of like mind familiar with the sea-ways beyond. This complex network of overlapping systems created a broad corridor of movement, at its extremes stretching between the ports of Andalucia and the islands of Shetland. In the Iron Age a family living in Cornwall had more in common culturally with a community in Brittany than it did with one in East Anglia or for that matter Hampshire.

Taking this more outward-looking perspective it is possible therefore to view Britain not centrifugally but centripetally – not as an entity but as a series of outward-looking zones. The map (2) helps to visualize this but like all helpful generalizations it is grossly over-simple. What it does do, however, is to provide a focus which redresses the imbalance caused by accidents of modern research. Looking at the Ordnance Survey Map of Southern Britain in the Iron Age one might form the impression that Wessex was the centre. Our fig.3, on the contrary, might be thought to suggest that Wessex was in fact a periphery – an inbetween land bordering other more distinctive zones with wider horizons. That we should be forced to reverse our perspectives occasionally is a healthy exercise and can sometimes lead to a better understanding.

Geographical determinism in archaeology is unfashionable and yet, looking at the landscape of Britain, one is forced to admit that the geomorphology of the island must have played a significant part in constraining the nature of settlement, thus influencing the social systems that could emerge. The issue was first given substance by Sir Cyril Fox in a brilliant introductory essay published as ThePersonality of Britain in 1932. Using the archaeological data then to hand Fox divided Britain into a highland and a lowland zone – it was essentially a north-west/south-east divide. While there is still much truth in this simple generalization, the picture needs to be modified. A more appropriate division of the land is between east and west. The predominantly upland nature of the west, from Dartmoor to the Grampians, combined with the present weather systems means that the western part of the country has a high rainfall of more than 100 mm per year while the eastern extremity of East Anglia has less than 60 mm. Factors of this kind would have created constraints directly affecting the food-generating regimes and this in its turn is likely to have offered some limitation to the socio-economic systems which developed. Add to this other factors such as differences in the number of hours of sunshine each July day – crucial to the ripening of crops – and the point that Britain exhibits considerable extremes of microclimate will become immediately apparent. In other words, in the past, as now, the kind of agriculture that could be practised on, say, the downs of Kent would simply not have been possible in the Outer Hebrides. The point may be self-evident but it needs to be stressed to explain the almost bewildering diversity in settlement and social systems apparent in the Iron Age, the more so then because the comparatively simple technologies available did not allow communities to override geography.

3 Britain presents a varied landscape which has had a significant influence on settlement pattern. Although the form of settlements varies very considerably from place to place it is possible to distinguish four broad zones of settlement type which, in part, reflect the natural regions of the country implying a close relationship between environment and the socio-economic system which it supports.

The land of Britain, then, presented to the prehistoric inhabitants a mosaic of microregions each with its own constraints and opportunities. The dynamic relationship between the social group and its environment generated a cultural landscape of great variety but standing back from the detail it is possible to generalize and to divide it into five broad zones: south-west, north-west, north-east, east and central south (3). It says much for the dominant role played by environment that even today this five-fold division is a useful generalization in attempting to understand social and economic differences.

Against the immutable structure created, in the first instance, by solid geology must be seen the far more subtle patterns of change caused by climatic variation and by anthropomorphic factors – the interference of man in his environment. These are difficult matters to untangle. A widely accepted view is that the first quarter of the first millennium bc saw a dramatic fall of 2°C in overall mean temperature. There was a slight improvement about the middle of the millennium and a return to colder conditions towards the end. Such a fluctuation sounds unimpressive but in reality it could have shortened the growing season by up to five weeks. For upland communities in the north, where summer sunshine was crucial for ripening the crop, such a fluctuation would have been disastrous. It is dramatically reflected in the swathes of abandoned landscapes, dating to the second and early first millennia bc, found in certain upland areas of northern and western Britain where communities were forced by changing climates to abandon traditional farmlands for the more congenial climates of lower altitudes (4, 5). Changes like these, even if they are spread over several centuries, are likely to have caused social disruption.

In parallel with these temperature variations there were also considerable changes in rainfall. From the late second millennium bc until about 700 bc the climate became noticeably wetter but after the middle of the millennium there was a return to drier conditions. In the west and in the highlands generally where precipitation was greatest, the effects of these changes would have been intensified. On Dartmoor it is possible to show that over this period the higher reaches developed thicker and more extensive peat bogs which drove settlement from the uplands. The recurring nature of this problem is nicely demonstrated by the brief recolonization of these same regions in the early Middle Ages and the rapid abandonment again as the climatic worsening of the fourteenth century took its toll. The environment on the fringes of settlement was fickle and in the abandoned farms of the early first millennium bc and early second millennium ad we witness the pioneering efforts of early inhabitants beaten back by nature.

4 An early landscape, probably of Late Bronze Age date, at Penhill in the Yorkshire Dales. The snow still lies in the ancient fields but has cleared from the field walls and the walls of the circular houses.

5 An abandoned Bronze Age settlement and its adjacent fields on Leskernick Hill, Altarnun, Cornwall. The hut circles can be clearly seen. The fields or paddocks are partially cleared of surface stone which has been used to build the walls.

Man’s ability to initiate irreversible changes in his own environment is now well understood. Deforestation and the extension of ploughed land are likely, over the broad sweep of the prehistoric period, to have wrought considerable change and as population increased and more land was brought under the plough so the rate of change would have accelerated. Work in the river valleys of the English Midlands shows that alluviation took place on a massive scale in the first millennium bc, completely changing the productive potential of huge tracts of land. Factors of this kind, together with the depletion of soil nutrients as the result of intensified cropping, cannot have failed to have had an effect on the way communities utilized their environment. In short, throughout the period which concerns us, the landscape of Britain was constantly changing. In some areas and at some times rate of change was rapid – for the local communities perhaps even catastrophic – elsewhere change would have been imperceptible. But that environmental change was a constant reality is a fact we must not forget.

To take stock – we have briefly explored three facets of the stage upon which the communities of Iron Age Britain were constrained to act out their lives: the local regions and their ease of access to the Continent; the structure of the land; and the subtle changes to which the environment was continuously subjected. The situation, then, was an infinitely subtle interplay between a fixed immutability and the restless dynamics of change.

Some communities because of their relative isolation and comparatively static environment changed little over considerable periods of time (6). Others occupying territories on or close to corridors of communication were open to external influences. Yet others, under pressure from their changing environments, were forced to evolve or die. Thus, there were conserving societies and innovating societies. The rate of change varied from area to area and from time to time but as a generalization we may say that for the most part the communities of the west experienced far less social change in the Iron Age than did those of the south-east. In Cornwall, for example, the basic settlement enclosure – the round – showed little change between the late second millennium bc and the late first millennium ad, whereas in the south-east an urban system had evolved, matured and all but disappeared during that span. The reason for this stark difference is that the two zones belonged to different interregional systems. The south-east, by virtue of its geographical proximity to the Continental heartlands, shared in the innovative forces which gripped the region facilitated in part by ease of communication and an overall agrarian fertility, while the west was part of a totally different regional system – the Atlantic zone – with its rugged face to the ocean a kaleidoscope of small self-contained communities – an outward-looking periphery.

6 The village of Rosemergy in West Penwith, Cornwall lies in the centre of a field system which very probably dates back to the prehistoric period. The present village may well lie above its prehistoric predecessor. Examples of such dramatic continuity are rare in Britain.

That today the same divide persists is a dramatic reaffirmation of a basic geographical truth. The fellow feeling of the so-called ‘Celtic west’ which brings Galician bagpipes regularly to perform in Breton fêtes folkloriques and makes economic sense of a regular ferry link between Cork and Roscoff, and the golden economic crescent – the so-called ‘hot banana’ – of Europe stretching from the English Midlands across northern France and Germany to the Po valley, are modern reflections of the power of the interacting forces which were already shaping Britain three millennia ago.

2THE PEOPLE: RACE, LANGUAGE AND POPULATION

Of these complex issues what can we possibly hope to know? The Roman historian, Tacitus, writing at the end of the first century ad, took something of a minimalist view. ‘Who the first inhabitants of Britain were,’ he wrote, ‘whether natives or immigrants remains obscure; one must remember we are dealing with barbarians’ (Tacitus, Agricola II). With that it is difficult to argue. Yet even the circumspect Tacitus cannot resist adding a few observations and speculations. The Britons’ physical characteristics vary, he notes, a variation which is suggestive. ‘The reddish hair and large limbs of the Caledonians [in Scotland] proclaim their Germanic origins, the swarthy faces of the Silures [in south-east Wales] the tendency of their hair to curl, and the fact that Spain lies opposite, all lead one to believe that Spaniards crossed in ancient times. ... The peoples nearest to the Gauls likewise resemble them ... it seems likely that the Gauls settled in the island lying so close to their shores.’ That there were physical differences between populations we can reasonably accept but Tacitus’s explanations are of course no more than speculation (7, 8, 9).

7 An attempt to visualize an Iron Age Briton. Reconstruction based on the well preserved body found in the bog at Lindow (see 9).

Another writer to take a passing interest in these matters was Julius Caesar who had the advantage of actually confronting Britons in their own country during his campaigns in 55 and 54 bc. In offering a brief background to his readers Caesar says of the Britons, ‘The interior ... is inhabited by people who claim, on the strength of their own traditions, to be indigenous. The coastal areas are inhabited by invaders who crossed from Belgium for the sake of plunder and then, when the fighting was over, settled there and began to work the land’ (Caesar, De Bello Gallico V,12). He goes on to add that the population, presumably of the south-east with which he was familiar, was extremely large.

INVASIONS AND THE CELTIC LANGUAGE

The opinions of Caesar and of Tacitus provided the foundations upon which the theories of nineteenth- and twentieth-century commentators were constructed. This is not the place to re-examine the development of archaeological thought on the subject but a brief comment must be offered. Some of the theories developed while the discipline was in its infancy are still occasionally, almost a century on, being stated as facts. The basic model adopted to explain the peopling of Britain was one of successive invasions from the Continent. It was a model consistent with the examples of recent history and one which could be claimed to have been given support by Caesar’s statements about settlers from Belgium.

8 Lindow Man, found preserved in a Cheshire bog. He had been ritually killed by strangulation, cutting his throat and a blow to the head. The deposition of bodies in bogs is a practice well known in northern Germany and Denmark but rare in Britain.

In 1890 Arthur Evans attempted to give some physical reality to these Belgic settlers by suggesting that a group of burials found at Aylesford in Kent could be ascribed to them. Further elaboration of the invasionist model came in the decade between 1912 and 1922 in theories developed by J. Abercromby, O. G. S. Crawford and H. Peake. It was Peake’s view that Britain received three distinct waves of invaders before the Belgae. The first in 1200 bc and the second in 900 bc were Goidelic Celts while the third about 300 bc were a group of Brythonic Celts. This model sought to link changes observed in material culture, represented in the archaeological record, to contemporary linguistic theories.

Linguists had characterized surviving Celtic languages into two groups, Goidelic which included Irish, Manx and Scots Gaelic, and Brythonic to which Welsh, Breton and Cornish belonged. The principal difference lay in the way in which the Indo-European QU was sounded. In Goidelic it remained a gutteral sound qu but in Brythonic it had been labialized to p. This difference is sometimes characterized as Q-Celtic and P-Celtic but is only one of the variations between the two dialects. Given the assumed antiquity of Q-Celtic and its distribution around the western extremity of the Celtic-speaking world it is easy to see how the theory developed that Q-Celtic spread first everywhere reaching the Atlantic seaboard and that the more ‘evolved’ P-Celtic was brought in later replacing the archaic Q-Celtic in Armorica, Cornwall, Wales and England, where a substratum of Brythonic place names could be found beneath those derived from the Latin, Germanic and Norman French spoken by later invaders. The theory had the advantage of being contained and elegantly simple and the successive incomings, which it implied, could be linked to virtually any archaeological assemblage that was considered to be sufficiently ‘foreign’ in appearance to allow it to be assigned to an invading group.

Much has, of course, been written on the subject in the last 70 years. The invasionist theory remained popular until the 1960s when it began to be challenged and soon fell from favour. Meanwhile the researches of linguists have shown just how complex and uncertain the early development of language can be. Later displacements of population could also have complicated the picture with Goidelic Celtic being carried to Scotland from Northern Ireland in the mid-first millennium ad and Brythonic being imposed on Armorica by settlers who were coming from south-west Britain at the same time.

9 A modern vision of an Iron Age warrior chief stands guard at the Museum of the Iron Age, Andover. Each piece of equipment is based on an actual example though there is some variation in the date. The clothing is largely speculative.

The old theories, which linked archaeological ‘evidence’ of invasion to the introduction of language groups, are examples of circularity in argument. As archaeologists abandoned invasionist theories, so linguists began to reassess their evidence. The general position now, widely held by many scholars in the field, is that the Indo-European language was introduced into Britain perhaps as early as the early Neolithic period and it was from this common base in Britain and much of western Europe that the Celtic language developed. The differences between Q-Celtic and P-Celtic would then be seen as the result of divergent development of language between different indigenous groups, owing nothing to successive waves of invaders. In other words, dialects of Celtic were to be heard over much of western Europe, along the Atlantic fringes in particular, long before the beginning of the first millennium bc. The differences between the Goidelic of Ireland and the Isle of Man and the Brythonic of Britain and probably Gaul would therefore most likely be the result of the relative isolation of the western islands in contrast to the contacts maintained by Britain and Gaul.

Tacitus, writing of the area of Britain close to Gaul, records that there was no great difference in language on the two sides of the Channel but goes on to tell us that the Britons of the south-east were eager, after the invasion, to learn Latin. Even so it is clear from place-name evidence, and from names recorded on lead tablets found in the sacred spring at Bath, that Celtic names persisted throughout the Roman occupation. In the west and north, in Cornwall, Wales, Ireland and Scotland, away from the heavy hand of Romanization and of the later Germanic incursions, the living language survived.

If, then, we can uncouple the language of Celtic from distinctive assemblages of archaeological material and concepts of folk movement, how ‘Celtic’ was Britain in the sense that it shared in what some writers have characterized as a pan-European Celtic culture, spread largely by folk movements arising in north-eastern France and southern Germany in the fifth century bc?