14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

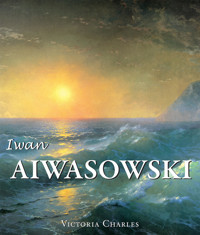

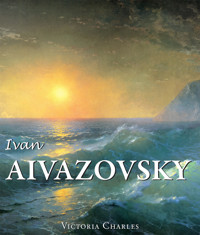

The seascapes of Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900) made his name in Russia, his native country where he was a painter of the court of Nicholas I, yet his fame barely extended beyond these borders. Master of the Sublime, he made the ocean the principal subject of his work. Sometimes wild and raging, sometimes calm and peaceful, the life of the ocean is composed of as many allegories as the human condition. Like Turner, whom he knew and whose art he admired, he never painted outside in nature, nor did he make preliminary sketches; hispaintings were the fruit of his exceptional memory. With more than 6,000 canvasses, Aivazovsky was one of the most prolific painters of his time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 125

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Authors: Victoria Charles

with the collaboration of Sutherland Lyall and Nicolaï Novouspenski

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-296-9

Victoria Charles

Ivan Aivazovsky

Contents

Foreword

The Russian Painters of Water

Ivan Aivazovsky

Biography

List of Illustrations

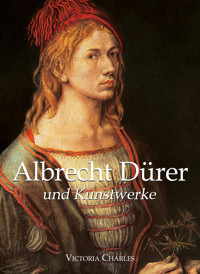

Self-portrait, 1892. Oil on canvas, 225 x 157 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

Foreword

Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky has been one of Russia’s most popular artists for over a hundred years, enjoying greater fame in his youth than most artists do in a lifetime. He was well-known amongst artists and the general public who adored his talent, and his celebrity spread quite quickly.

Near the start of his artistic career he was elected to various foreign academies and even had the honour of having his self-portrait displayed in the Pitti Gallery in Florence, only the second Russian artist to have been bestowed this honour after Orest Kiprensky.

Aivazovsky’s achievements were well-deserved as no other artists managed to encompass the most difficult of subjects, the changing ambience of the sea, with such intensity and precision.

However Aivazovsky was not merely a professional seascape painter. He understood and loved the sea but it did not limit him to only seascapes. If he tried his hand at other subjects, such as landscapes or portraits, they were but a brief escape from the sea to which he devoted his life.

Seascape painters divide themselves into three categories: those who live by the sea with the preoccupation of accurately relaying what they see before them; those who live by the beach a couple of months a year and copy moments or incidents which strike them from the shore or the harbour; and finally, the landscapists that haphazardly paint the sea or make use of it to add to a painting, giving it a bit of depth.

Seascape painters have become rarer, because paintings of the sea are unrewarding. Amateur collectors do not often seek out seascape paintings and it is only when an artist acquires some celebrity in this genre that they buy their work so that their name will be present in their collection; the subject rarely influencing the buyer. Admirers of the sea are primarily found in little groups of poets, writers, and sailors.

The education of a seascape painter is one of the toughest and most difficult. To paint the sea, one must have sailed in all the seasons, passed days and weeks at sea, studied the sky and the water, and when all the necessary documents are acquired, back in the studio, be able to execute credible works of art.

One must also know how to put a boat in water: how many paintings are there where the boat, cut off by the line of the sea, looks like a child’s toy placed on a mirror that reflects it, because the water does not wet it and it is not in the water, it is simply placed on top.

It is also difficult to really grasp the anatomy of the waves and render them in their coming-and-going movement, to represent the cliffs in their picturesque forms, in their geological structure. An infinite list of these types of observations could be made.

Depicting the open sea in good or bad weather is more difficult than to paint the picturesque beaches on which we can see the world of elegant people going about their lives, sailors, shrimp fisherwomen, pretty women easy on the eye. The first paintings require a great deal of effort; the second ones come much more easily.

In short, it is only in living the life of the people of the sea that a maritime painter learns their trade and can really examine this forever changing model that we call the ocean.

Aivazovsky’s artistic career began in Russia at the time when Romanticism was in full swing and played an important role in the development of landscape art during the second half of the 19th century. Romanticism is present not only in his early works but in a large majority of his later canvases. Shipwrecks, fierce naval combats, and storms remained his favoured themes.

In keeping with the great Russian landscape artists from the start of the 19th century, and without ever imitating anyone, Aivazovsky created his own school and his own traditions which distinctly mark the maritime genre as of his time and of future generations. In his works we can also remark upon the apparent traits of Armenian culture as he remained loyal to his people and country for the duration of his life.

The Great Roads in Kronstadt, 1836. Oil on canvas, 71.5 x 93 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

The Frigate“Aurora”, 1837. Oil on canvas, 75 x 101 cm. Private collection.

The Russian Painters of Water

Water and its Symbolism

Water is key to the formation of the world and human society. It is one of the four primeval elements from which, people once believed, the whole world was made. Water certainly was – and still is – the principal force whose eroding power forms the features of the land over eons of geological time. Today it separates the earth’s continents from each other. The first human settlements were made near water, beside lakes, rivers and sea shores. According to various ancient beliefs, water once drowned the whole world, and then receded to allow humankind to make a fresh beginning.

Water is still used to baptise people into various religions. It is the giver of life and the bringer of death. Without it the human body survives for just two days. It irrigates food crops and yet it may impartially obliterate thousands of people in a single tsunami. Frozen as snow and ice, it vanquishes armies. As fog it can make even brave sea captains fearful.

Water embraces all extremes from limpid tranquillity to cataclysmic violence. It is therefore not surprising then that water has been a pervasive element in art, architecture, and landscape design. It has been used to symbolise the source and sustenance of life.

It has served as a representation of nature’s mysteries, as a physical barrier and boundary, and as sparkling decoration. Painters have been fascinated with its misty, reflective qualities, and its ability to underline and sometimes represent a whole range of emotions.

As marsh and lake, mist and snow, puddle and ocean, waterfall and driving rain, deadly flood and slow moss-banked stream, it has an extraordinary diversity of forms. But because it is contained and defined by the very land it has shaped, it can never exist entirely in isolation. Water always needs a physical or metaphorical container: it can exist meaningfully only within a context. For these reasons, the representation of water in painting is most frequently as an element of nature, implying that it is best understood in terms of landscape painting.

The Kronstadt Raid, 1835. Oil on canvas, 124 x 199 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

Sea View, 1841. Oil on canvas, 74 x 100 cm. Private Collection.

But this is not exactly always the case because water is also frequently employed in a symbolic way. In Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, for example, the iconography of the myth demands that the sea be present because that is where Venus has sprung from – although in terms of composition the sea serves as an almost heraldic background device.

In Curradi’s Narcissus at the Source, it is only a small part of the painting and yet we know that it is the water that initiated the whole process which leads the young man in the most extreme of transformations from human to vegetable form. In the Curradi painting it is not only the water but also the landscape that is an adjunct to the painting of the main figure.

But it is in paintings of nature – landscapes or seascapes – that water is deployed most expressively, whether it is in the glowing landscapes of Claude Lorrain, or in a painting such as Arkhip Kuindzhi’s The Birch Grove.

In this, scarcely differentiated from the meadow to each side, the stream is used as a compositional device to lead the viewer’s eye into the centre of the painting to create the extraordinary sense of depth which astonished the artist’s critics.

In the great range of sea paintings by the prolific Ivan Aivazovsky, it is significant that he chose the sea as the setting for his almost abstract The Creation of the World. Here a mysterious red magma boils in the middle of an uncertain black cloud on the face of the waters seething vapour, with a febrile sun breaking through the cloud to cast a dim light on the heaving waters. This is God moving on the face of the Deep.

In Isaak Levitan’s Beginning of the Spring, three forms of water – cloud, river, and snow – are (apart from the brown branches recently released from their icy covering) the sole visual components of a painting to do with awakening and, perhaps, regret. And there are, as we shall see, many other variations in the use of water that painters have developed.

The Shipwreck, 1843. Oil on canvas, 116 x 189 cm. Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia.

Port of Valletta in Malta, 1844. Oil on canvas, 61 x 102 cm. The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

View of the Venetian Lagoon, 1841. Oil on canvas, 76 x 118 cm. Peterhof State Museum-Reserve, St Petersburg.

Levitan, Kuindzhi and, in a different way, Aivazovsky painted water with a peculiarly Russian eye. They are, as it happens, painters of the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century. One of the reasons Russian paintings of waterscapes and landscapes are of a relatively late date is that from the beginning of the 18th century Peter the Great and almost all of his successors in that century forced the Old Russia into a western mindset.

Russian art was entirely derivative of European models, and at first largely filtered by a Prussian vision, because Peter had brought in masters from Germany to teach aspiring Russian artists the ways of the West.

As a result, the nation’s artists were encouraged to think of themselves as part of the European mainstream, and were given grants to live, observe, and paint abroad for long periods of time. But at the beginning of the 19th century, with a new western interest in landscape and landscape painting, Russian artists began to both value and encourage the painting of nature, mountains, and water.

At first this was landscape viewed through the filters of a western-trained eye and consisted mostly of idyllic European scenery. But by the end of the century, Russian painting of water and land had become to do with the Russian landscape and identifiably took on a uniquely Russian character.

The country has the Pacific Ocean to the far east, and to the west is the Baltic Sea, with its gateway St Petersburg and the naval port of Kronstadt. South is the warm Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, with their resorts and trading ports fed by the great, broad waterway of the River Volga, which bisects the country into the East and West Empire. To the north, beyond the great wastes of the Siberian tundra, are the cold seas that form the mostly frozen Arctic Ocean. During the long winter, as Napoleon and Hitler discovered to their cost, much of Russia is frozen over.

Russia is geographically defined by its water in all of its three physical states: vapour, liquid, and translucent solid. The brutality, manic depression, melancholy, and gloom, which in many ways seem to typify the Russian national character, surely stem from a collective agoraphobia engendered by the country’s grim winter climate of rain, mists, fogs, snow, and ice. This is of course an oversimplification, for the south of Russia has a relatively equable climate – as the paintings of Aivazovsky, who spent most of his life in the Crimea, nicely demonstrate. And the spring, summer, and autumn could be delightful, as many of the painters of the late 19th century discovered.

But people need stereotypes, and the image of Russia held by foreigners and Russians alike has largely been of melancholy, tragedy, and callous rawness among those frozen rivers; damp, fog-bound cities; and ice-locked seas.

Even before Peter the Great built his new capital on the Neva, Russia’s rivers, lakes, and seas had formed a crucial transport network for the pastoral and often nomadic Russian people. In the late 19th century, Russia was not only a huge country, but still an essentially rural empire in which the boundless forests and plains were crisscrossed by streams, rivers, and lakes which were ever mobile. They changed shape and colour as the seasons changed. Indeed there is a Russian Orthodox ceremony known as The Consecration of the Waters at Epiphany. The Volga, one of a group of great continental Russian rivers, is not merely an extremely long and broad waterway. It holds a special place for Russians as a massive artery that feeds the country’s very heart, ranging from the wintry extremes of the north to the soft pleasures and seas of the south.

So Levitan, Kuindzhi, Aivazovsky, Arkhipov, and Repin, to name but a few of the great Russian painters of water, were not only celebrating a major feature of the visible landscape they knew, loved, and so obsessively painted but were also celebrating an incredible gamut of emotions and moods. These range from stark terror to peaceful tranquillity, from deep sorrow to exalted musing, and from delightful contentment to uneasy foreboding.

Venice, 1842 (?). Oil on canvas, 115.5 x 187 cm. Peterhof State Museum-Reserve, St Petersburg.

Water in Russian Cities

As a serious artistic activity, Russian painting really dates only from the 19th and 20th centuries. As the Russian Symbolist poet Alexander Block put it, “Russian culture is a combination of cultures, we are a new country”. Block’s new country was actually synthetic and coldly calculated – created at the beginning of the 18th century with Peter the Great’s westernisation of Old Russia. This had often been carried out with great brutality. And in some ways so too had Peter’s introduction of western culture, art, and architecture.