9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

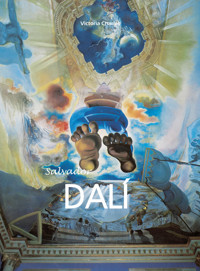

As a one of the foremost painters of the 20th century, Dalí, like Picasso and Warhol, can boast of having overturned the art of the previous century and directed contemporary art toward its present incarnation. As irrational as he was surrealist, this genius diverted objects from their original meanings, plunging them into the acid of his constantly churning imagination. A megalomaniac and an artist who understood above all the force of marketing and publicity, Dalí disorientates the viewer in order to draw him into the artist’s world. On his canvases, images and colours crash together to express and mock certain ideas, creating a subversive eroticism that taps into the subconscious of the avid voyeurs that we are. The author, Eric Shanes, explores the twists and turns of Dalí’s mad genius, commenting on the masterpieces of the painter so as to show the diversity and scope of his talent, leaving the reader blown away and bewitched by this Prince of Metamorphosis. This work opens up the sweet, mad universe of this megalomaniac genius and invites us to let ourselves be overcome … Dalí is, first and foremost, an absolute.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 121

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

VICTORIA CHARLES

Text: Victoria Charles

Designer: Thu Nguyen

© Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image Barwww.image-bar.com

© ARS, New York/ VEGAP, Madrid

© Kingdom of Spain, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/ ARS, New York

ISBN: 978-1-64461-844-8

All rights reserved worldwide.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case we would appreciate notification.

Contents

The Public Secret of Salvador Dalí

The Years of the King Childhood and Adolescence in Figueras and Cadaqués

From Outsider to Dandy The Student Years in Madrid

A Friendship in Verse and Still-Life Dalí and Garcia Lorca

The Cut Eye Dalí and Buñuel

Gala or The Healing Gradiva The Surrealist Years in Paris

The Pictures behind the Pictures Paranoia as Method

Between Worlds First Successes in America

Break out into Tradition The Renaissance of the Universal Genius as Marketing Expert

Metamorphosis to Divine The Time of Honour and Riches

Biography

Index

Notes

Chapter 1

The Public Secretof Salvador Dalí

At the age of 37, Salvador Dalí wrote his autobiography. TitledThe Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, the Spanish painter portrays his childhood, his student days in Madrid, and the early years of his fame in Paris up to his leaving to go to the USA in 1940. The exactness of his descriptions are doubtful in more than one place. Dates are very often incorrect, and many childhood experiences fit too perfectly into the story of his life. As Dalí had studiously read the works of Sigmund Freud and Otto Rank, his autobiography like his painting, is imbued with applied psychoanalysis. The anecdotes, memories, and dreams that comprise Dalí’s autobiography were, one suspects, deliberately chosen.

The picture that Dalí drew of himself in 1942, and further developed in the years up to his death in 1989, shows an eccentric person, most at ease when placed in posed settings. Despite this tendency, Dalí often revealed intimate details of his life in front of the cameras. This act of self-disclosure, as Dalí explains in his autobiography, is a form of vivisection, a laying bare of the living body carried out in the name of pure narcissism:

“I perform it with taste – my own – and in the Jesuit manner. But something else is valid: a total section is erotically uninteresting; this leaves everything just as unfathomable and coiffeured as it was before the removal of the skin and flesh. The same applies for the bared skeleton. In order to conceal and at the same reveal, my method is to gently intimate the possible presence of certain internal wounds, while at the same time, and in a totally different place, plucking the naked sinews of the human guitar while never forgetting that it is more desirable to let the physiological resonance of the prelude ring out, than experience the melancholy closing of the full circle.”[1]

The more Dalí showed himself in public, the more he concealed himself. His masks became ever larger and ever more magnificent: he referred to himself “genius” and “god-like”. Whoever the person behind Dalí really was, it remains a mystery. “I never know when I start to simulate, or when I am telling the truth”, he professed in an interview with Alain Bosquet in 1966, “In any case the audience should never be allowed to guess if I am joking or being serious; and I am certainly not allowed to know either.”[2]

1.Portrait of Lucia, 1918. Oil on canvas, 43 x 33 cm, Private collection.

Chapter 2

The Years of the King Childhood and Adolescence in Figueras and Cadaqués

Dalí’s memories appear to begin – or so Dalí informs us in his autobiography – two months before his birth on May 11th, 1904. Recalling this period, he describes the “intra-uterine paradise” defined by “colours of Hell, that are red, orange, yellow and bluish, the colour of flames, of fire; above all it was warm, still, soft, symmetrical, doubled and sticky.”[3]

His most striking memory of birth, of his expulsion from paradise into the bright, cold world, consists of two eggs in the form of mirrors floating in mid-air, the whites of which are phosphorising:

“These eggs of fire finally merged together with a very soft amorphous white paste; it appeared to be drawn out in all directions, its extreme elasticity which molded itself to all forms appeared to grow along with my growing desire to see it ground down, folded, rolled-up and pressed out in the most different directions. This appeared to me to be the pinnacle of all delight, and I would have gladly have had it so always! Technical objects were to become my biggest enemy later on, and as for watches, they had to be soft or not at all.”[4]

Dalí’s life is overshadowed by the death of his brother. On August 1st, 1903, the first-born child of the family, scarcely two years old, died from gastroenteritis. Dalí himself claimed that his brother had already reached the age of seven and became ill with meningitis. In preparation for an exhibition on Dalí’s formative years, in London in 1994, Ian Gibson examined the dead brother’s birth and death certificates and determined that the painter’s statement was incorrect. Gibson also pointed out that Dalí’s accusation – that his parents had given him the name of his dead brother – was only partly true. In addition to being given the first forename of the father, both were also given two second names. The first-born was baptised Salvador Galo Anselmo, and the second, Salvador Felipe Jacinto.[5]

Regardless, the child Salvador sees himself as nothing more than a substitute for the dead brother:

“Throughout the whole of my childhood and youth I lived with the perception that I was a part of my dead brother. That is, in my body and my soul, I carried the clinging carcass of this dead brother because my parents were constantly speaking about the other Salvador.”[6]

Out of fear that the second-born child could also sicken and die, Salvador was particularly coseted and spoiled. He was surrounded by a cocoon of female attention, not just spun by his mother Felipa Doménech Ferrés, but also later by his grandmother Maria Ana Ferrés and his aunt Catalina, who moved into Dalí’s family home in 1910. Dalí reported that his mother continually admonished him to wear a scarf when he went outdoors. If he got sick, he enjoyed being allowed to remain in bed:

“How I loved it, having angina! I impatiently awaited the next relapse – what a paradise these convalescences! Llucia, my old nanny, came and kept me company every afternoon, and my grandmother came and sat close to the window to do her knitting.”[7]

Dalí’s sister Ana Maria, four years younger, writes in her book,Salvador Dalí visto por su hermana (Salvador Dalí, seen through the eyes of his sister), that their mother only rarely let Salvador out of her sight and frequently kept watch at his bedside at night, for when he suddenly awoke, startled out of sleep, to find himself alone, he would start a terrible fuss.[8]

Salvador enjoyed the company of the women and especially that of the eldest, his grandmother and Lucia. He had very little contact with children of his own age. He often played alone. He would disguise himself as a king and observed himself in the mirror:

“With my crown, a cape thrown over my shoulders, and otherwise completely naked. Then I pressed my genitals back between my thighs, in order to look as much like a girl as possible. Even then I admired three things: weakness, age and luxury.”[9]

Dalí’s mother loved him unreservedly, even lionized him. With his father, Dalí enjoyed a different type of relationship. Salvador Dalí y Cusi was a notary in the Catalan market-town of Figueras, near the Spanish-French border. His ancestors were farmers who moved to the Figueras area in the middle of the 16th century. Dalí himself claimed that his forefathers were Moslems converted to Christianity. The family name, unusual in Spain, stems from the Catalan word “adalil”, which in turn has its roots in the Arabic and means “leader”.[10]

Dalí’s grandfather, Galo Dalí Viñas, committed suicide at the age of thirty-six after losing all his money speculating on the stock-exchange. Dalí’s father grew up in the home of his sister and her husband, a Catalan nationalist and atheist. His influence over his young brother-in-law was considerable: vocationally, Dalí’s father followed in his footsteps, choosing to study law, and matured into an anti-Catholic free thinker. Because of this, he decided not to send his son Salvador to a church school, as would have befitted his social status, but to a state school. Only when Salvador failed to reach the required standard in the first year did his father allow him to transfer to a Catholic private-school of the French “La Salle” order.

2.Dutch Interior (Copy after Manuel Benedito), 1914. Oil on canvas, 16 x 20 cm. Joaquin Vila Moner collection, Figueras.

3.Self-Portrait in the Studio, c. 1919. Oil on canvas, 27 x 21 cm. The Salvador Dalí Museum, St Petersburg (FL).

4.Portrait of the Cellist Ricardo Pichot, 1920. Oil on canvas, 61.5 x 49 cm. Private collection, Cadaqués.

5.The Sick Child (Self-Portrait in Cadaqués), c. 1923. Oil and gouache on cardboard, 57 x 51 cm. The Salvador Dalí Museum, St Petersburg (FL).

6.Portrait of Hortensia.Peasant Woman from Cadaqués, 1920. Oil on canvas, 35 x 26 cm. Private collection.

7.Self-Portrait with the Neck of Raphaël, 1920-1921. Oil on canvas, 41.5 x 53 cm. The Gala-Salavdor Dalí Foundation, Figueras.

8.Portrait of José Torres, c. 1920. Oil on canvas, 49.5 x 39.5 cm. Museum of Modern Art, Barcelona.

There, among other things, the eight-year-old learned French, which was later to become his second mother tongue, and received his first lessons in painting and drawing. In 1927, in the magazineL’Amic de les Arts, Dalí wrote about the brothers of the order, saying they had taught him the most important laws of painting:

“We painted some simple geometrical forms with watercolours, sketched out beforehand in black right-angled lines. The teacher told us that good painting technique in this case, and in general, good painting consists of the ability to not paint over the lines. This art teacher [...] knew nothing about aesthetics. However, the healthy common sense of a simple teacher can be more useful to an eager student than the divine intuition of a Leonardo.”[11]

At about the same time as Salvador was receiving his first lessons from the brothers of the “La Salle” Order, he set-up his first atelier in the old, disused wash-room in the attic of his family home:

“I placed my chair in the concrete basin and arranged the high-standing wooden board (that protects washerwomen’s clothing from the water) horizontally across it so that the basin was half covered. This was my workbench! On hot days I sometimes took off my clothes. I only needed then to turn on the tap, and the water that filled the basin rose up my body to the height of my belt.”[12]

Apparently Dalí painted his first oil painting in this wash-basin. The oldest existing works, however, date from the year 1914. They are small-format watercolours, landscape studies of the area around Figueras. Oil paintings by the eleven-year-old also exist, mostly as copies of masterpieces which he found in his father’s well-stocked collection of art books, and in particular theGowan’s Art Books. Salvador spent many hours studying the reproductions and was particularly enthusiastic about the nudes of Rubens and Ingres.[13]

For Salvador, the atelier became the “sanctuary” of his loneliness:

“When I reached the roof I noticed that I became inimitable again; the panorama of the city of Figueras, which lay at my feet, served most advantageously for the stimulation of my boundless pride and the ambitions of my lordly imagination.”[14]

His parent’s home was one of the largest in the city. In the laundry room-atelier the little king tried out a new costume:

“I started to test myself and to observe; as I performed hilarious eye-winking antics accompanied by a subliminal spiteful smile, at the edge of my mind, I knew, vague as it was, that I was in the process of playing the role of a genius. Ah Salvador Dalí! You know it now: if you play the role of a genius, you will also become one!”[15]

Later Dalí analysed his behavior:

“In order to wrest myself from my dead brother, I had to play the genius so as to ensure that at every moment I was not in fact him, that I was not dead; as such, I was forced to put on all sorts of eccentric poses.”[16]

His parents supported this eccentric behavior by showering him with extra attention. They told their friends proudly that their son was alone “up there” for hours painting. For Dalí, the expression “up there” became the symbol of his extraordinary standing.

Salvador’s attempts to distance himself from his dead brother went so far that he believed himself immortal. Descending the stairs one day at school, it suddenly occured to him that he should let himself fall. But at the very last moment fear held him back. However, he worked out a plan of action for the next day:

“At the very moment I was descending the stairs with all my classmates, I did a fantastic leap into the void, and landing on the steps below bowled over and over until I finally reached the bottom. I was thoroughly shaken and my whole body was crushed, but an intense and inexplicable joy made the pain seem incidental. The effect on the other boys and the teachers who ran over to help me was enormous. [...] Four days later I repeated the action again but this time I launched myself from the top during the long break, just as the school-playground was at its most animated. [...] The effect of my plunge was even better than the first time: before I let myself go, I let out a piercing scream, making everybody turn and look. My joy was indescribable, and the pain caused by my fall was, in comparison, a mere trifle. This spurred me on to continue my ventures and from time to time I repeated the stunt. Each time, just as I was descending the stairs a huge tension prevailed. Will he jump or won’t he? What fun it was to walk down quietly and normally and to know that at that moment a hundred pairs of eyes were fixed on me in greedy anticipation.”[17]