9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

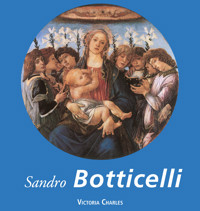

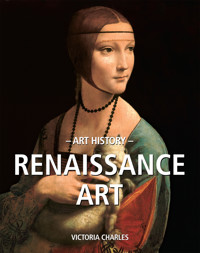

The Renaissance began at the end of the 14th-century in Italy and had extended across the whole of Europe by the second half of the 16th-century. The rediscovery of the splendour of ancient Greece and Rome marked the beginning of the rebirth of the arts following the break-down of the dogmatic certitude of the Middle Ages. A number of artists began to innovate in the domains of painting, as well as sculpture and architecture. Depicting the ideal and the actual, the sacred and the profane, the period provided a frame of reference which influenced European art over the next four centuries. Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Giorgione, Mantegna, Raphael, Dürer and Bruegel are among the artists who made considerable contributions to the art of the Renaissance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 59

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Victoria Charles

– ART HISTORY –

RENAISSANCE

© 2024, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2024, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 979-8-89405-016-4

Contents

Introduction

I. Art In Italy

The Italian Early Renaissance

The Italian High Renaissance

Leonardo Da Vinci

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Raphael

Painting In Middle And Upper Italy

Painting In Venice

II. Art In France

III. Art In Germany

Albrecht Dürer

Hans Holbein The Younger

Lucas Cranach The Elder

IV. Art In The Netherlands

List Of Illustrations

Piero di Cosimo, Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci, c. 1485. Oil on panel, 57 x 42 cm. Musée Condé, Chantilly.

INTRODUCTION

What had been started by the primi lumi, the ‘first lights’, in the art of painting progressed in the fifteenth century and acquired a new historical sense, causing artists to look back before the Middle Ages to the world of classical civilisation Italians came to admire, almost worship, the ancient Greeks and Romans for their wisdom and insight, and for their artistic and scholarly achievements. A new kind of intellectual, the humanist – a scholar of ancient letters who promoted humanist philosophy – fuelled this cultural revolution. Humanism fostered the belief in the study of nature and the potential of humankind, along with a sense that secular, moral beliefs were necessary to supplement the limited tenets of Christianity. Above all, the humanists encouraged the belief that ancient civilisation was the apex of culture, and that writers and artists should be in a dialogue with those of the classical world. The result was the Renaissance – the rebirth – of Greco-Roman culture. The panels and murals of Masaccio and Piero dell Francesca captured the moral firmness of ancient Roman sculptural figures, and due to the new science of perspective portrayed them as part of our physical world. The Renaissance perspective system is based on a single vanishing point and carefully worked out transversal lines, resulting in a spatial coherence not seen since antiquity. Even more clearly indebted to antiquity were the paintings of the northern-Italian prodigy, Andrea Mantegna. His archaeological studies of antique costumes, architecture, figural poses and inscriptions resulted in the most consistent attempt by any painter to recreate Greco-Roman civilisation. Even a painter like Alessandro Botticelli, whose art evokes a dreamy spirit that had survived from the late Gothic style, created paintings with Venuses, Cupids and nymphs that responded to the subject matter of the ancients and appealed to contemporary viewers touched by humanism.

It would be better to think of ‘Renaissances’ rather than a single Renaissance. This is demonstrated most clearly by looking at the art of the leading painters of the High Renaissance in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Giorgio Vasari saw these masters as setting out to create an art greater than nature, as idealists who improved on reality rather than imitated it, and who evoked reality thoughtfully rather than delineating it in every detail. We recognise in these painters different embodiments of the cultural aspirations of the time. Leonardo da Vinci, trained as a painter, was equally at home in his role as a scientist, and incorporated into art his research into the human body, plant forms, geology and psychology. Michelangelo Buonarroti trained as a sculptor, subsequently turning to painting to express his deep theological and philosophical beliefs, especially the idealism of Neoplatonism. His muscular, over-life-size and intense heroes could hardly differ more from the graceful, smiling, supple figures of Leonardo. Raphael of Urbino was the ultimate courtier, whose paintings embody the grace, charm and sophistication of life at Renaissance courts. Giorgione and Titian, both Venetian masters, focused on luxurious landscapes and sumptuous female nudes, using colour and free brushwork to express an Epicurean sense of life. Titian’s motto Natura Potentior Ars, ‘Art more powerful than nature’, could be the philosophy of all sixteenth-century artists. One the achievements of Italian Renaissance painters was to establish their intellectual credentials. Rather than mere craftsmen, artists – some of whom, such as Leon Battista Alberti, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, were themselves writers on this subject – made a bid to be considered on a par with other thinkers of their time, and helped raise the profession of painting in Renaissance Italy.

A kind of cult sprang up around leading artists of the time, with Michelangelo, for example, called Il Divino, ‘the divine’. Already in 1435, Alberti urged painters to associate themselves with men of letters and mathematicians, which paid off. The present-day inclusion of ‘studio art’ in university curricula has its origins in this new attitude to painting that arose in Italy during the Renaissance. By the sixteenth century, rather than commissioning particular works, art patrons across the Italian peninsula were happy to acquire any product of the great artists: acquiring a Raphael, Michelangelo or Titian was a goal in itself, regardless of the work in question.

While Italian Renaissance artists created highly organised spatial settings and idealised figures, northern Europeans focused on everyday reality and on the variety of life. Few painters have equalled the Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck, for example, in his close observation of surfaces, and captured more clearly and poetically the glint of light on a pearl, the deep, resonant colours of a red cloth, or the glinting reflections that appear in glass and on metal.

Sandro Botticelli (Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi),Madonna of the Book, c. 1483. Tempera on wood panel, 58 x 39.5 cm. Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan.

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna with the Child and Two Angels, 1465. Tempera on wood, 95 x 62 cm. Galleria degi Uffizi, Florence.

Hieronymus Bosch, Haywain (triptych), 1500-1502. Oil on panel, 140 x 100 cm. San Lorenzo Monastery, El Escorial.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding, c. 1568. Oil on wood, 114 x 164 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienne.

Scientific observation was one form of realism, while another was the intense interest in the bodies of saints and the anatomical details of the Passion of Christ. This was the age of religious theatre, when actors, dressed as biblical characters, acted out in churches and on the streets the detail of Christ’s suffering and death. It is no coincidence this was also the period when masters such as the Netherlandish Rogier van der Weyden and the German Matthias Grünewald painted, sometimes with excruciating clarity, the wounds, streams of blood and pathetic countenance of the crucified Christ. The northern masters executed their painting using the skilled technique of oil, in which they excelled in Europe until the Italians adopted the medium in the later fifteenth century.

Spanning both north and south Europe during the Renaissance was Albrecht Dürer of Nuremburg. Durer followed the Italian practice of canonical measure of the human body and perspective, though he retained the emotional expressionism and sharpness of line that was widespread in German art. Though he shared the optimism of Italians, many other northern painters were pessimistic about the human condition. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s essay on the Dignity of Man