Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: John Donald

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

James V suffered the fate of many a son of a famous father in being somewhat overshadowed not only by his father James IV but also by his internationally renowned daughter Mary Queen of Scots. But no-one would deny the importance of his reign, embracing as it did the establishment of the Court of Session, the birthpangs of religious dissent, and the growth of royal power to such a remarkable extent that this king could leave his kingdom for nine months in 1536-7 without fear of rebellion. Jamie Cameron concentrates on James V's style of government and relations with his nobility, and challenges the widely held view of a vindictive and irrational king, motivated largely by greed, who antagonised most of his leading magnates and met his just deserts when they refused to support him in 1542. This book offers a different view, and presents us with a rounded picture of a king whose approach to government, in spite of some personal defects, closely resembles that of his supposedly more popular father; and, like James IV himself, retained impressive magnate support to the end of his reign.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 992

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JAMES V

Jamie Cameron (1962–1995)

First published in Great Britain in 1998 by Tuckwell Press The Mill House Phantassie East Linton East Lothian EH40 3DG Scotland

Copyright © The Dr Jamie Stewart Cameron Trust, 1998

ISBN 1 86232 015 4 hardback 1 86232 004 7 paperback

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text Limited, Edinburgh Printed and bound by Biddles Ltd, Guildford

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword

Editor’s Note

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Conventions

1. ‘Ill Beloved’? James V and the Historians

2. The Assumption of Royal Authority

3. The Struggle for Power: July to November 1528

4. Royal Victory?

5. The Assertion of Royal Authority in the Borders

6. Poisoned Chalice? The Douglas Connection

7. The Major Magnates and the Absentee King

8. National Politics and the Executions of 1537

9. The Rise and Fall of Sir James Hamilton of Finnart

10. Daunting the Isles

11. Wealth and Patronage

12. 1542

13. The Final Weeks of the Reign

14. ‘The Most Unpleasant of all the Stewarts’?

Appendices:

I: The Sources for the Reign

II: Charter Witnesses

III: Parliamentary Attendances

Bibliography

Index

List of Illustrations

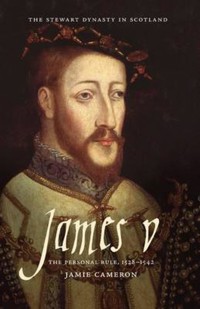

The title page illustration, a silver groat showing a profile of James V wearing an imperial crown, is reproduced by permission of the National Museums of Scotland

1. James V

2. James V and Madeleine

3. James V and Mary of Guise

4. The Royal Arms of Scotland

5. Statue of James at Stirling Castle

6. Bonnet pieces

7. Tantallon Castle

8. Craignethan Castle

9. Holyrood Palace and Abbey

10. Falkland Palace from the north

11. Falkland Palace from the north-west

12. Falkland Palace: the south range

13. Stirling Palace: the east front

14. Linlithgow Palace: courtyard, fountain and east facade

15. Linlithgow Palace: the south facade

16. Stone medallions from the north range of Falkland Palace

17. Oak medallions from the King’s presence chamber at Stirling Palace

MAPS

French Holiday of James V (1536–1537)

The Projected Marriages of James V

Itineraries of James V: 1526 to 1531

Itineraries of James V: 1533 to 1537

Itineraries of James V: 1538 to 1542

Foreword

Until comparatively recently, the character and policies of James V suffered from both scholarly and popular neglect. Little was written about the personal rule of this elusive Stewart monarch, perhaps because the careers of his more famous father James IV, and his internationally renowned daughter, Mary Queen of Scots, offered more immediately attractive themes for historians of the sixteenth century. Furthermore, the personal rule of James V stands alone, separated in time by fifteen years from the disaster of Flodden and the elimination of James IV with a large part of his nobility in 1513, and by close on nineteen years after James V’s death in 1542 until the personal rule of his daughter Mary.

Fortunately a number of recent scholarly works have helped to shed light on some of the obscurity hitherto surrounding the reign. These include Carol Edington’s masterly study of the period, Court and Culture in Renaissance Scotland: Sir David Lindsay of the Mount (1994); the wide-ranging volume of essays on Scottish literature, music, and heraldry contemporary with, and in some cases emanating from, James V’s court, edited by Janet Hadley Williams under the title Stewart Style 1513–42: Essays on the Court of James V (1996); and Athol Murray’s magisterial Edinburgh thesis (1961) on Exchequer and Crown Revenue (1437–1542), parts of which have been published over the years. Forthcoming is a major study of James V’s court by Andrea Thomas.

All these works indicate an encouraging growth of interest in this hitherto neglected reign; but none of them is, or claims to be, a study of crown-magnate politics during the personal rule, an aspect of the reign which has long cried out for scholarly analysis. Instead of such analysis, we have Caroline Bingham’s racy, readable, and inaccurate portrait of the king (James V, King of Scots, 1513–1542 (London, 1971)), heavily dependent for its views on the post-Reformation chronicler Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie. More important is Gordon Donaldson’s hugely influential chapter on King James’s policies in Scotland: James V – James VII (The Edinburgh History of Scotland, volume Three: 1965); but its influence has hardly been beneficial, for other scholars have not really sought to challenge Donaldson’s view that James V should be regarded with revulsion as a vindictive king who created a sense of insecurity amongst his subjects and who ultimately practised something of a reign of terror against his nobility. Far too much of this is surely the result of reading history backwards rather than forwards; James V, as the committed representative of the Auld Alliance and of Catholicism, has to be condemned in order to justify the Scottish Reformation and its political corollary, alliance with England. Thus the savaging of the king’s reputation began early with the malicious outpourings of John Knox, and has been sustained, with few exceptions, down to the present day. All that has been salvaged is the image of James as a poor man’s king, an elusive concept which might be applied to many Stewart kings, or at least to one view of themselves which they sought to publicise.

Dr. Cameron offers us a different portrait of James V, seeing him as a ruler whose policies bear a strong resemblance to those of his popular father. Thus both kings exploited the wealth of the Church in order to finance their wars; both relied heavily on the pursuit of feudal casualties in order to build up royal income; both indulged in legal sharp practice to extract money from their subjects; both ultimately adhered to the Franco-Scottish alliance because it proved financially lucrative to them; both mixed Arthurian myth and the reality of the Anglo-Scottish marriage of 1503 to remind Henry VIII of their closeness to the English throne; and both expended huge sums on the outward trappings of monarchy – on palaces, pageantry, even a royal navy.

These are striking similarities; however, there exists one major difference between father and son, namely the circumstances in which each came to power. James IV succeeded aged fifteen, and took over the reins of government, early in 1495, at the relatively advanced age of twenty-two, without conducting any purge of household or state officials. No such luxury was possible for James V. Succeeding as an infant of eighteen months, he had to endure close on fifteen years of fractious minority, in which – not for the first time – the king became a pawn in the struggles of the major political players – Albany, Arran, Angus, and the queen mother Margaret Tudor – and found himself effectively a prisoner of the Angus Douglases from 1526 to 1528. Dr. Ken Emond has argued that, given the divisions amongst the key political players in 1526, Archibald, sixth earl of Angus, probably felt that he had no option but to retain the person of the young king as a bulwark to the Douglases’ continuing power; the alternative was to sacrifice political influence and risk being overwhelmed by rivals and enemies. Hence Angus’s coup d’état of 1526, and his subsequent lavish distribution of offices in household and state to his family, including the Chancellorship for himself.

Thus the young James V, on taking control of government in the summer of 1528, had no option but to do so by staging a further coup d’état with the objective of removing Chancellor Angus and his entire family. This was a messy and only partially successful operation, involving an abortive royal siege of Angus’s castle of Tantallon in 1528, protracted military and diplomatic efforts to drive the earl out of southern Scotland, and, once Angus had taken refuge in England, to prevent his return. This lack of a clean break in 1528 certainly coloured James V’s relations with his magnates and with the English for much of the personal rule; but as Dr. Cameron shows, the Scottish king did not act in an irrational or vindictive way towards the Second Estate. It is true that he warded most of the principal Border lords in 1530; but this was an essential process given that the threat from Angus remained very real and that the king had to begin by securing a clear acknowledgement of his authority in the south. Significantly Robert, fifth Lord Maxwell, one of the most prominent of the borderers, remained loyal in spite of being warded; indeed, he was subsequently granted control of Liddesdale, made Admiral of Scotland, and as the king’s trusted counsellor escorted Mary of Guise to Scotland in 1538.

The classic exception to this general rule of a loyal nobility during the personal rule is the young and foolish Patrick Hepburn, third earl of Bothwell, who in December 1531 offered to assist Henry VIII in an invasion of Scotland. Given his blatant treason, Bothwell’s punishment – warding followed by exile – was light, and hardly serves as a demonstration of the king’s supposed vindictiveness. And Bothwell’s treasons stand out sharply from the norm, which was of a Second Estate supportive of James V from beginning to end of the personal rule, so much so that the king could confidently appoint four of them to govern the country during his absence in France for close on nine months in 1536–7.

It would seem, therefore, that, as Dr. Cameron argues, the extent of crownmagnate tensions during the personal rule has been grossly exaggerated. Certainly there were instances of Stewart sharp practice directed against weak targets amongst the nobility – the earls of Crawford and Morton are cases in point – but royal threats of disinheritance were not carried into effect, and James V seems simply to have been extending his popular father’s forceful use of the device of recognition – that is, to make money, not to strip his subjects of their inheritances. Unlike James IV, however, James V was hardly generous in his distribution of royal patronage.

The modern perception of James as a grasping and vindictive king is based, as Dr. Cameron shows, on rather selective use of contemporary evidence. That great mine of information about the court, the Treasurer’s Accounts, becomes much less effusive in this reign than in the previous one, with the result that one tends to turn for evidence to the ‘bible’ of the period, the published letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of Henry VIII, with their wealth of Scottish material. Uncritical reliance on this source, however, carries its dangers, due to an understandable English bias in the reporting of Scottish events. James V was, after all, a king who made two French marriages, flouted his English uncle’s wishes, and resolutely opposed any return to Scotland of the English-backed Archibald, earl of Angus. Thus English comments on James V’s policies and character are frequently severely critical of the king. For example, Thomas Magnus’s 1529 warning to King James about the dangers of using ‘yong Consaill’, citing the fate of the Scottish king’s grandfather as a result, is not only threatening in its language but also quite inaccurate in content; while the Duke of Norfolk’s notorious remark of 1537, much quoted out of context, that ‘so sore a dread king, and so ill-beloved of his subjects, was never in that land’, is to some extent English wishful thinking and needs to be taken with a very large pinch of salt.

However, the English were not alone in seeking to condemn James V for his supposed cruelty. The Scottish border ballad of the reiver Johnie Armstrong – updated in recent times by John Arden’s play ‘Armstrong’s Last Goodnight’ – presents us with the ‘graceless face’ before which Armstrong pleaded in vain for mercy; but this was surely also the face of a resolute Stewart monarch performing one of his primary duties as king, that of punishing thieves and reivers. James V’s ruthlessness in performing this task again recalls his father’s driving of the justice ayres; and generations of writers on kingship, from Bower to Boece, would certainly have approved. Nor, as Dr. Cameron also shows, is there any need to explain the executions of the Master of Forbes and Lady Glamis as evidence of a streak of sadistic cruelty in the king’s nature. An alternative approach, followed here, is to assess the reasons for their indictment, and to consider the question of their guilt or innocence.

There are problems, too, in accepting the post-Reformation view that James V was a ‘priestis king’, in the pocket of the First Estate and swimming stubbornly against the inexorable tide of religious change. It is true that scholarly opinion is likely to remain divided over the extent and importance within Scotland of laymen with reforming opinions; but Dr. Cameron is surely right to be deeply sceptical of the existence of the king’s ‘black list’ of heretics – 360 of them, with the earl of Arran at the head of the list and including most of the major Scottish magnates. Significantly, this list was first mentioned in March 1543, after James’s death, by Sir Ralph Sadler, the English ambassador in Scotland, and Sadler’s information may be no more than a gross inflation of earlier English reports that there had been disputes in the Scottish king’s council in 1542.

However, such tensions as there were did not deprive James V of very wide support from the First and Second Estates in the autumn war of 1542. In the course of this, the Earl of Huntly won a battle at Hadden Rig, the Duke of Norfolk abandoned invasion plans and went home in October, and in a sideshow on the Solway in November, Lord Maxwell was defeated and captured by Sir Thomas Wharton. Early in December, King James made plans to renew the conflict. It was his death at Falkland on the 14th of that month, more likely from cholera or dysentery rather than excessive nervous or mental stress brought on by the news of Solway Moss, which created an immediate crisis at court and made possible early assaults on his reputation.

Yet, as Dr. Cameron shows, acting as an advocate in James V’s defence can easily be overdone. Wide magnate support for his policies does not in itself make him a popular king; indeed, there is virtually no trace of enthusiastic endorsement of James V in the few surviving contemporary Scottish sources. Even the praise of Sir David Lindsay, employed by the king throughout the personal rule and eventually promoted to Lyon Herald, is rather muted. In ‘The Complaynt’, Lindsay, it is true, makes approving noises about James’s enforcement of law and order in the Highlands and on the borders; but in the ‘Testament of the Papyngo’, Lindsay’s lavish praise of James IV – as ‘the glore of princelie governyng’, as the king who ‘daunted’ the ‘Savage Iles’, Eskdale, Ewesdale, Liddesdale and Annandale, and as the prince whose tournaments attracted contestants from all over northern Europe – leaves us in no doubt as to the identity of the poet’s Renaissance paragon. And it may be no accident that while Lindsay credits James IV with organising famous jousts (one of which, at Holyrood in 1508, the poet may have witnessed), the best he can manage for James V is a contest between two Household servants, James Watson and John Barbour.

This rather homely image may simply suggest that, in the early years of the personal rule, James V did not fire Lindsay’s imagination to the same extent as the king’s father. Yet even as early as 1530, Lindsay reflects on the Arthurian imagery of the ‘tabyll rounde’ at Stirling, and offers conventional advice to the king on the guidance of his ‘Seait Imperiall’. Both these themes would be developed by James V in the latter stages of his reign, and there can be little doubt that the French visit and marriage of 1536–7 marks the watershed of the personal rule. Before 1536 James had been preoccupied with domestic issues, with the continuing problem of the Earl of Angus, and with the spectacular opportunities afforded to him by the playing off of a heretic England against a Catholic Europe. On his return from France in May 1537, he had resolved these issues, had indeed acquired a more prestigious French marriage than had seemed possible even a few years before. Even Madeleine’s speedy death did not impair the Franco-Scottish alliance, and James V was soon in receipt of another enormous dowry for his second wife, Mary of Guise-Lorraine.

Thus in what proved to be the last years of the reign, King James displayed an aggressive confidence which was reflected in his renewal and extension of ‘imperial’ themes whose origins, as Roger Mason has shown, can be traced back to James III in 1469. These themes centre round representations of the closed imperial crown, depicted, for example, on the contemporary portrait of James V and Mary of Guise, and on the superb gold ‘bonnet piece’ of 1539; while early in 1540 the Scottish imperial crown was itself remodelled and enriched for James V’s use at the coronation of his queen at Holyrood in February 1540. These very tangible examples of the Bartolist concept that the king is emperor within his own realm were complemented by the astonishing royal building programmes at Falkland and Stirling, essentially the creation, at enormous cost, of French Renaissance palaces within the short time frame of 1537–1542. And King James’s circumnavigation of his realm in the summer of 1540 may in part reflect his ‘imperial’ view of his kingship; this was a voyage made to emphasise the prestige of a prince in control even of the remotest areas of his kingdom.

In the last analysis, our view of the character and policies of James V is probably formed by our response to the simple fact of his very early and unexpected death. Had he lived, a clearer and probably more complimentary verdict would have been delivered on the personal rule; for the 1540s would then have developed with a young, powerful, and solvent Scottish king in full command of his realm, facing an ageing and ailing English ruler whose legacy was a disputed succession, deep religious divisions, a hostile Europe, and an empty treasury. In the fullness of time, Mary of Guise would have added to her tally of royal Stewart children, securing a smooth adult succession; and the close alliance with France would have led to the earlier enjoyment by the Scots of those huge financial outlays which the French deployed in Scotland in the late 1540s and 1550s, and which Marcus Merriman has so graphically described.

It was not to be. All Stewart kings took some unfinished business with them to their graves; but perhaps James V took more than most.

Norman Macdougall Series Editor

EDITOR’S NOTE

The tragic death of Jamie Cameron in April 1995 not only deprived us of an able and thoughtful historian whose skills were still developing, but also created the immediate problem of deciding what to do with his work on James V; for Jamie had barely started on the lengthy process of converting his successful Ph.D. thesis into a book. However the importance of the subject, the author’s original and challenging views, especially on crown-magnate relations and Anglo-Scottish diplomacy, and the encouragement of friends and colleagues, soon convinced me that Jamie’s work ought to be edited and published as quickly as possible. If this is not the finished book which Jamie Cameron himself would have produced – he would, for example, have developed important themes such as the relationship between church and crown and the king’s policy towards Ireland – it is nevertheless an important and in many ways radical review of royal policy in a reign which until recently was neglected by scholars and which is still widely misunderstood.

As editor I have tried throughout to avoid being too interventionist, largely leaving the author’s work to speak for itself, which for the most part it does extremely eloquently. Here and there I have altered passages for the sake of clarity; I have removed some of the scholarly scaffolding necessary to sustain a thesis, but perhaps less welcome in a book; and I have added an index.

I should like to record my thanks to Aileen Cameron, the inspiration for this publication of James V from the very beginning; to John and Val Tuckwell, that ideal publishing duo for harassed writers; and to Margaret Richards, who having undertaken the complex and often problematical task of word-processing the thesis, found herself reliving the whole experience for the book, and did so with unfailing patience, skill, and good humour.

Norman Macdougall Editor

DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is dedicated to my father-in-law Joseph G.S. Cameron, W.S., who as Jamie said ‘would have liked to have done this sort of thing’. This is the dedication on Jamie’s doctoral thesis.

Like his father Jamie had a good academic brain. He graduated from St. Andrews University with M.A. Honours in History, then from Edinburgh University with LL.B. with distinction. He was a qualified solicitor at the time of his death. He completed his doctorate at St. Andrews University under the supervision of Dr. Norman Macdougall. Jamie had a great love of Scottish History and believed strongly in its importance.

I am grateful for the opportunity to record my thanks to Norman Macdougall, without whose patience, understanding, guidance and tolerance this book, and in fact its source (the Ph.D.), would not have been completed. Jamie had great respect and affection for Norman and was grateful to him for all his efforts and indeed inspiration. Thanks must also go to Simone Macdougall (and Bonnie) for her friendship throughout the years.

Jamie was lucky to have excellent flatmates, and I would like to thank Dr. Bruce F. Gordon and Dr. Andrew Colin on Jamie’s behalf for the good times they had together.

Finally Jamie would also have liked to have thanked his long time friends Andrew Gardner and Dr. Andrew Petersen for the many long and detailed academic discussions they had, whether it was in the hills he loved, our home in Edinburgh, or at Balgonie with Celia, Jamie’s mother.

In recognition of Jamie’s concern for Scotland, the Scottish people and Scottish History, its study and research, a settlement on Trust was made after Jamie’s death. The Trust is called the Dr. Jamie Stuart Cameron Trust, and it was set up to assist postgraduate students of Scottish Mediaeval History. The net proceeds of the sale of this book will benefit the Trust Fund, which is administered by Anderson Strathern, W.S., Edinburgh.

Aileen A. Cameron Edinburgh, 6 February 1998

CONVENTIONS

Dates are given according to the modern calendar with the New Year beginning on 1 January.

Wherever possible the contractions used in the text to describe printed works are drawn from: List of Abbreviated Titles of the Printed Sources of Scottish History to 1560 (SHR, Supplement, October, 1963). Otherwise, abbreviations are as cited in text and bibliography.

CHAPTER ONE

‘Ill Beloved’? James V and the Historians

The received view of James V is of a king who was very successful at making money: this was commented upon by Lesley and Buchanan, writing in the latter part of the 16th century, and again by Donaldson and Mitchison four hundred years later. Indeed these latter two historians have considered the pursuit of wealth to be the prime driving force behind all of James’ policies.1 A quick look at the account books for the reign confirms this impression. Total revenue in 1530–31 was under £24,000 Scots. In 1539–40 it was over £50,000 Scots, almost four times as much as it had been in 1525–26.

Casualty income doubled between 1530 and 1542, while Household costs and other expenditure rose to keep pace with this income.2 Other sources of revenue were available to the king in the form of taxation (of the Church, burghs and laity); two vast marriage dowries (together worth almost £170,000 Scots); and the appointment of his illegitimate sons to vacant benefices (perhaps yielding £10,000 Scots each year).3 James’ expenditure on royal palaces was partially financed from casualties, but largely through taxation of the Church.4 A great proportion of this income did not even pass through the account books. When the king died in 1542, he left £26,000 in his treasure chest at Edinburgh castle, which sum was quickly dispersed in his daughter’s minority. Knox narrated how in his last few weeks James made an inventory of all his wealth.5

In the context of crown-magnate relations this pursuit is said to have made him extremely unpopular. Through blending financial extortion with unpredictable strikes against some magnates James managed to alienate the bulk of his nobility. By taking the counsel of members of the royal Household (and its subdepartment the Scottish church6) he denied the ‘natural’ advisers of the monarchy – the Second Estate – the opportunity of remedying the situation. The personal rule ended in humiliation at Lauder in the course of the last week of October 1542. There the decision was taken to disband the Scots host, despite the recent presence on Scottish soil of the ‘auld enemy’, engaged in burning Kelso abbey and the neighbourhood some twenty-five miles to the south east. The inference taken from this episode is that the lords of Scotland had been driven into refusing to acknowledge that most fundamental feudal concept – to support the king in war. Less than a month later, the fiasco of Solway Moss provided enough good copy for later historians to complete their demolition of James V’s political career; at Solway Moss, a Scots army was supposedly thrown into confusion by the efforts of a member of the royal household – Oliver Sinclair – to get himself appointed as its captain. The man supposedly in command – Lord Maxwell – was captured by the English together with two earls and four other lords. Later it was revealed that Maxwell allowed himself to be taken and in fact held Lutheran views. He and his magnate colleagues had taken advantage of the confusion to defect to the ‘auld enemy’. In Scotland James V’s chief regret was that Sinclair was also captured. James died of nervous exhaustion – or perhaps of a broken heart? Few regretted the passing of this ‘terrifying’ and ‘vindictive’ Stewart king.7

The verdict is that the king could not establish a working relationship with his magnates, hence their lack of support for him at the end of the reign. James V is seen as an example of complete failure.8 John Knox simply stated that some called him a murderer of the nobility.9 James’ approach to crown-magnate relations was epitomised in dramatic form in 1537 with the executions of the Master of Forbes and Lady Glamis, and emphasised in 1540 by the execution of James Hamilton of Finnart – all three found guilty of treasonably plotting regicide. The burning of Lady Glamis on the castle hill at Edinburgh has particularly excited the pens of some historians (though the contemporary chronicler Adam Abell was content merely to note the bald facts10). Their judgements have ranged from ‘an accident’ through to ‘almost unprecedented vindictiveness’.11 Whether or not she was guilty (even if only on the balance of probabilities) is almost an afterthought. However, it was in the context of the events immediately following her death that James was dubbed ‘ill-beloved’ by the Duke of Norfolk.12

Other examples of James’ approach to politics include his exiling of the third earl of Bothwell and annexation of his lands; and his imprisonment of the fourth earl of Argyll in 1531, of the archbishop of St. Andrews, James Beaton, in 1533, and of the third earl of Atholl in 1534. This last earl, according to Pitscottie and Bingham, had in 1530 entertained the king in a palace especially built for the royal visit. There the king, together with his mother, Margaret Tudor, and the papal ambassador, were wined and dined (with gingerbread, claret and swans on the menu) at Atholl’s expense – which amounted to £3000 Scots in total.13 Additionally, James hounded the eighth earl of Crawford for nonentries – reducing him, in Michael Lynch’s words, ‘to a near cipher of the court’.14 In 1541 James attempted to relieve the disabled third earl of Morton of his earldom. Further down the social scale, in the early summer of 1530 the king warded several of the Border lords and lairds – including all three wardens of the Marches – and hanged the notorious Johnnie Armstrong of Gilknockie. The ballad recording this event inspired one historian to thunder that James had the attitude of a schoolboy. Possibly less well known is that in July of the same year, Lord Maxwell, newly out of ward, presented James with a fresh sturgeon, perhaps by way of a thank you for the gift of the escheat of the late John Armstrong.15

The Armstrong episode also reflects the image of James V as ‘the poor man’s king’ (first noted by Knox and Chalmers). Bishop Lesley and Buchanan credited James with ease of access to the poor and a sense of justice that drove him to act against their oppressors. This is partially borne out by several civil cases brought before the newly created court of session by ‘puir tenants’. James also revived the idea of legal aid, by appointing an ‘advocate of the poor’.16 Records show that the king visited the Borders in almost every year of the reign, and that justice ayres were frequent and lucrative. The wardens were urged to apprehend thieves, but it was Johnston of that Ilk – a trouble maker under Angus – whom the author of the Diurnal of Occurrents credits with the capture of George Scott of the Bog. Donaldson has used Scott’s execution by burning at the stake to illustrate graphically James’ cruelty rather than his sense of justice.17

The touchstone to crown-magnate relations throughout the entire personal reign of James V is considered by some historians to be the tension between the king and the Douglases. This theme is sustained throughout – from the sixteenth century author of the Diurnal, commenting that the king had a ‘great suspicion’ of where his temporal lords’ sympathies lay, to Dr. Wormald, who comments on the king’s ‘hounding’ of those bearing the surname Douglas.18 (It is perhaps worth noting here that in 1540 Patrick Hepburn, bishop of Moray, remarked on how James appeared to penalise those of the surname Hepburn19). Dr. Kelley considers that James’ malice in the last few years of the reign reached ‘illogical and alarming proportions’, shown by his gullible reactions on hearing rumours of Douglas-inspired treason.20 Certainly the adult rule of James V caused a hiatus in the Scottish career of the sixth earl of Angus, and possibly it is the obviousness of this fourteen year gap which creates the touchstone. Magnate domination was totally incompatible with adult Stewart monarchy, as the Boyds had discovered in the reign of James III.21 Purging those families which held power in the minority was nothing new in James V’s reign. However, Dr. Emond has argued that the memory of earlier minorities was not a major influence on the consciousness of either the Douglases or the king.22

The majority rule of James V can be measured against the reigns of his forebears. The trend set by Wormald and followed by Lynch has been to compare and contrast the individual careers of the first five Jameses against the background of ‘a growing corporate image of the Stewart dynasty’. Each individual king simply refined and extended the methods employed by his predecessors to make money. Each moved towards a position of autocracy. Each died before achieving this position, and the subsequent minority restored the balance in Crown-magnate relations.23

The greed of the royal Stewarts was first encountered in James I’s reign. The act of revocation, which enabled the Crown to re-acquire land granted out in a royal minority and regrant the same (at a price), was first passed by James II. He also saw that ready cash could be made from feu farming. Apprising – the forced sale of land for debt – first occurred in James III’s reign. He also experimented with recognition – the repossession of a fief by the superior for illegal alienation by the vassal of the greater part. In James IV’s reign 119 instances of apprising and 149 instances of recognitions are recorded in the great seal register. Apprisings were not necessarily for debts owed to the Crown; but exacting payment to avoid recognition was a great money spinner for the Crown as well as being extremely unpopular.24 So it is perhaps surprising that James V did not use this method of financial extortion, although he was well aware of the legal theory.

The vast majority of the two thousand-odd great seal charters issued in the reign relate to confirmation by the Crown of sales and grants made by third parties. However there are recorded numerous grants, confirmations of grants, and grants in feu farm. Of the one hundred-odd grants of apprised lands only a handful represent debts due to the Crown – almost invariably for nonentries. Nonentry payments affected, amongst others, the earls of Lennox and Crawford, dating from the death of their forebears at Flodden. One extreme example was the attempt to recover one hundred and fifty years’ worth of nonentries for the lands of Kincraig in Fife from Walter Lundy of that Ilk, which was reduced by the Lords of Council and Session to fifty-two years.25 The Crown raised numerous summons of error, not all of which were successfully pursued. Compositions for ward, relief, marriage and nonentry made up a significant portion of the Crown’s casual revenue – some £2500 out of £13,000 in 1530, and £6000 out of £25,700 in 1542. Other compositions for charters were of much less significance, save for exceptional ones such as the £1333 paid by the fourth earl of Huntly for the feu of Braemar, Strathdee and Cromar in 1530. The proceeds from justice ayres and remissions were of greater importance.26 Taxation supplemented these feudal methods, as it had for James IV.

James V followed the example of his ancestors in making money out of his revocation. He also used forfeiture – most notably of the Douglases – to obtain land. Kelley has pointed out that with the sole exception of the Regality of Abernethy – granted to the earls of Argyll – all of the forfeited Angus lands were either in the direct or indirect control of the king long before their formal annexation to the Crown in 1540.27 This points up the other factor at issue in the manipulation of magnates’ resources by any Stewart king – their redistribution in the form of patronage to win support. This was something that James III was bad at and James IV good. The received opinion of James V is that he ‘did not love the nobility’, and in this respect was akin to his maternal grandfather.28

Patronage reflected the individual style of each Stewart king. If the methods employed by James V to make money can be said broadly to have followed along the same lines as those of his predecessors, then it was rather the style of politics practised by him that earned him his reputation amongst his contemporaries and produces the verdict of later historians. There was of course the question of circumstances. In James V’s case the coinciding of his adult rule with the growth of the European Reformation has provided various verdicts on the reign29. The growing influence of the Lutheran doctrine prompted the Church to begin examinations of heretics, and these on occasion directly involved the king. Abell recorded the presence of James V at the trials of Mr. Norman Gourlay and David Stratoun in Holyrood Abbey in 1534. Both men were subsequently burned. Such repression incited the fury of John Knox, who described James as an ‘indurate tyrant’.30

Others have criticised the king for his religious policy. Bingham considered that James’s early death saved him from increasing unpopularity through its pursual.31 That religious issues played an important part in Scottish diplomacy is certain; negotiations between James and his uncle, Henry VIII, involved debates over doctrine and the advantages or disadvantages which would result from dismantling the monasteries. James also wrote reassuring letters to the Papacy and received the approval of Charles V. The effect on Crown-magnate relations of Lutheranism is more difficult to gauge. It was a useful political ploy for James to threaten his over-taxed clergy with the fate of their English colleagues under Henry VIII if they did not toe the line. Possibly the supposed existence of a ‘blacklist’ of heretical laymen (headed by the name of the man who first advised Sir Ralph Sadler of its existence, namely the second earl of Arran, governor of Scotland in 1543) made an impression. Perhaps Lord Maxwell used the ploy of coming out as a Lutheran to impress his English captors in 1542. In any event, it is claimed that the most damaging aspect of religion on James’ politics was that he was seen to be closeted in the counsel of the First Estate to the exclusion of the Second. Pitscottie’s version of the failure of 1542 has the nobility saying of the king that ‘he was ane better preistis king nor he was thairis.’32 Hence the verdict on James’ career is that he had the makings of a financial tycoon but as managing director was not popular with the rest of the board.

There are problems with this verdict. It is not necessarily inaccurate. The temptation is to leap to the defence of the Stewart likened to a Tudor.33 Contemporary English reports dissuade one from so doing. There are virtually no traces of approval – though there are also virtually no contemporary Scottish opinions. Exceptions include Sir David Lindsay, whose works were written in the knowledge that his annual salary of £40 as herald was paid from the Household.34 In the ‘Complaynt’ he praises the king for the law and order brought to the Borders and Highlands. The performance of the Epiphany ‘Interlude’ at Linlithgow in 1540 emphasises the need for the clergy to toe the line. The anonymous ‘Strena’ praises James unreservedly, but dates from 1528.35 Adam Abell appears to be strictly factual, in that his account is substantiated by other records. He devotes the greater part of his work to damning Henry VIII; but he also narrates James’ use of disguise in his visit to the duke of Vêndome’s court in 1536. (The theme of disguise was taken to extreme lengths by Scott with his tales of ‘the guidman of Ballengeich’).36 The events of the reign are well recorded in primary sources (though the principal unpublished sources – the Acta Dominorum Concilii and Acta Dominorum Concilii et Sessionis – are not user-friendly); and it must be admitted that the events upon which the hostile verdict of James V is based did, by and large, occur.

The first problem is that the verdict rests upon too few premises. Instances of oppression, extortion and execution are used rather in the manner of stepping stones to arrive at the verdict. This ignores other events of the reign. The second problem is that these stepping stones themselves may not be as wholly secure as they appear. For example the downfall of Sir James Hamilton of Finnart – seen as the last straw in political relations by some historians – was considered by Buchanan to be no great loss and Knox passed no judgement.37 The third problem is one of contradictions, best illustrated in the careers of individual magnates. The ‘Lutheran’ Maxwell was one of James’ staunchest supporters, acting as vice-regent in 1536–37. The exiled Bothwell was responsible in part for the expulsion of Angus in 1528–29. The imprisoned Argyll and disaffected Moray of 1531 were reliable warlords on the Borders in later years. The fourth problem is that other events of the reign suggest stable relations and co-operation between the king and his nobility. James spent nine months in France in 1536–37 without worrying about sedition back home, and in 1540 attempted the daunting of the Isles with magnate support. The fifth problem is in the interpretation of 1542. Lynch has suggested that the nobility refused to fight in defence of the realm; others have considered that the Scots army was refusing to go on the offensive; contemporary reports suggested a dire shortage of supplies for English and Scots armies alike.38

The final problem is that the verdict of failure in Crown-magnate relations relies more on description than on explanation. Such explanation as there is is general – whether due to religious policy, the culmination of the sharp practice of Stewart monarchy over the previous four reigns of adult kings, or simple greed. There has to be more to the rule of James V than this.

NOTES

1. J. Lesley, The History of Scotland from the Death of King James I in the Year 1436 to the Year 1561 [Lesley, History], (Bannatyne Club 1830), 167; G. Buchanan, The History of Scotland [Buchanan, History], translated J. Aikman (Glasgow and Edinburgh, 1827–1829), 2 vols., ii, 265; Rosalind Mitchison, A History of Scotland (2nd edn. 1982), 93; Gordon Donaldson, Scotland: James V – James VII (Edinburgh History of Scotland, vol. 3, 1965), 44.

2.Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland [TA], vols. v-viii (1515–1546) ed. J.B. Paul (Edinburgh, 1903–1908), v, 407, 462; vii, 250, 361; viii, 10, 117; The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland [ER], vols. xv–xviii (1523–1542), ed. J.P. McNeill (Edinburgh, 1895–1897), xvi, 127–45; xvii, 269–97; Atholl Murray, ‘Exchequer and Crown Revenue of Scotland, 1437–1542’ [Murray, Revenues] (Ph.D., Edinburgh University, 1961), 120.

3. Murray, Revenues, 322, 340–1; Donaldson, op.cit., 46; cf. Michael Lynch, Scotland: A NewHistory (London, 1992), 164, estimates over £40,000 Scots from benefices per annum.

4.TA, v, 389, 433; vi, 33–4, 151, 232, 363; vii, 231, 502; Accounts of the Masters of Works [MW], vol. i (1529–1615), ed. H.M. Paton (Edinburgh, 1957), 114, 195, 234, 263, 292.

5.Registrum Secreti Sigilli Regum Scotorum [RSS], vols. i-ii (1488–1542), edd. M. Livingstone and J.B. Paul (Edinburgh, 1908–1921), ii, no. 383; Murray, op.cit., 346; John Knox, The History of the Reformation in Scotland [Knox, History], ed. W.C. Dickinson (Edinburgh 1949), 2 vols., i, 33.

6. Lynch, op.cit., 155.

7. Donaldson, op.cit., 52 (vindictive); Jenny Wormald, Mary Queen of Scots: a Study in Failure (London, 1988), 32 (terrifying).

8. Lynch, op.cit., 165; Wormald, Court, Kirk and Community: Scotland 1470–1625 [Wormald, Court], (New History of Scotland vol. iv, London, 1981), 12; Donaldson, op.cit., 60; Mitchison, op.cit., 89; Caroline Bingham, James V: King of Scots, 1512–1542 (London, 1971), 184, 188, 191; also comments on James V in Henderson, The Royal Stewarts (London, 1914); S. Cowan, Royal House of Stuart (1908); P.F. Tytler, The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III to the Union (Edinburgh, 1868), v, 299; P. Hume Brown, History of Scotland to the Present Time (Cambridge, 1911), i, 314–6; J.D. Mackie, A History of Scotland (Penguin, 1969), 140; less damning are Andrew Lang, A History of Scotland from the Roman Occupation (Edinburgh and London, 1900), i, 453; and Eric Linklater, The Royal House of Scotland (1970), chapter 4.

9. Knox, History, i, 35.

10. National Library of Scotland, [NLS] MS 1746 (Adam Abell, ‘The Roit and Quheill of Tyme’), f. 126v. The portion of Abell’s work which relates to the reign of James V has been translated and assessed by Alasdair M. Stewart, ‘The Final Folios of Adam Abell’s ‘The Roit or Quheill of Tyme’ in Janet Hadley Williams (ed.), Stewart Style, 1513–42: Essays on the Court of James V (East Linton, 1996), 227–253.

11. Sir Walter Scott, Miscellaneous Works of, vol. xxiii, Tales of a Grandfather, (II History of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1870), 45; Lynch, op.cit., 164.

12.Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII [LP Henry VIII], 21 vols. (1509–1547), edd. Brewer et al (1862–1932), xii pt. ii, no. 696.

13. R. Lindesay of Pitscottie, The Historie and Cronicles of Scotland [Pitscottie, Historie], (STS, 1899–1901), 3 vols., i, 335–8; Bingham, op.cit., 89–90.

14. Lynch, op.cit., 153.

15. Cowan, op.cit.; TA, v, 380; RSS, ii, no. 702.

16. Knox, History, i, 35; Chronicles of the Kings of Scotland (Maitland series, 1830), 86; Lesley, History, 167; Buchanan, History, ii, 264. Instances of poor tenants being represented at Court can be found in Scottish Record Office [SRO], CS6 (‘Acts of the Lords of Council and Session’) [ADCS], xi, f. 133 (‘poor tenants of Nisbet’); xii, f. 139 (‘poor tenants of Bothwell’). The idea of legal representation for the poor dates from a 1424 statute; cf. Introduction to Scottish Legal History (Stair Society, xx), 417. The appointment of an ‘advocat vocatus pauperum’ took this one stage further: SRO, ADCS, vi, f. 62; cf. RSS, ii, no. 3261.

17.A Diurnal of Remarkable Occurrents that have passed within the country of Scotland since the death of King James the Fourth till the year 1575 [Diurnal of Occurrents], 15; Donaldson, op.cit., 62.

18.Diurnal of Occurrents, 12; Wormald, Court, 12.

19. Fraser, Grant, iii, no. 91.

20. Michael Kelley, ‘The Douglas Earls of Angus: A Study in the Social and Political Bases of Power of a Scottish Family from 1389 until 1557’ [Kelley, Angus] (Ph.D., Edinburgh University, 1973), 748.

21. Norman Macdougall, James III: A Political Study (Edinburgh, 1982), 85.

22. William K. Emond, ‘The Minority of King James V, 1513–1528’ (Ph.D., St. Andrews University, 1988), ii, 360.

23. Wormald, Court, 9–13; Lynch, op.cit., 152–5.

24. Macdougall, James IV (Edinburgh, 1989), 160–3; Nicholson, R., ‘Feudal Developments in Late Medieval Scotland’, JR, 1973 (1), 13, 17.

25. SRO, ADCS, xv, f. 96v.

26.TA, v, 338, 344–9, 356; viii, 6, 12.

27. Kelley, Angus, 494–5.

28. Donaldson, op.cit., 55, 62.

29. Lynch, op.cit., 162, subtitles his chapter ‘James V: new problems, old solutions?’

30. Knox, History, i, 22.

31. Bingham, op.cit., 194–6.

32. Pitscottie, Historie, i, 402.

33. J.H. Burton, The History of Scotland (2nd ed., Edinburgh, 1873), iii, 186; Donaldson, op.cit., 62.

34.ER, xvi, Pref, xlv-li, 12, 464.

35.LP Henry VIII, xv, no. 114; The Works of Sir David Lindsay of the Mount, 1490–1555 (ed. D. Hamer, S.T.S., 1930–36), [Lindsay, Works], i, 50; ‘Strena Ad James V’, in Bannatyne Miscellany, iii (Bannatyne Club, 1827–55).

36. Abell, op.cit., f.125v; LP Henry VIII, xi, no. 631; Scott, op.cit., 21–5.

37. Buchanan, op.cit., ii, 261; Knox, op.cit., i, 22; cf. Donaldson, op.cit., 58; Wormald, Court, 12.

38. Lynch, op.cit., 165; cf. Lang, op.cit., i, 453; Bingham, op.cit., 183; Donaldson, op.cit., 59; LP Henry VIII, xvii, nos. 996, 1025.

CHAPTER TWO

The Assumption of Royal Authority

In June 1528, James V was sixteen years old and Scottish affairs were directed by his thirty-eight year old Chancellor, Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus.1

Angus had been the dominant figure in Scottish government since at least July 1525. The scheme then devised by the lords in parliament was for the physical custody of the royal person to be rotated amongst his subjects. The safekeeping of the young king was entrusted to one group of leading politicians for a three-month period only, at the end of which a second group would take over for the following quarter succeeded in turn by a third and fourth group. Angus, his kinsman James Douglas, third earl of Morton, and Gavin Dunbar, archbishop of Glasgow, were principal amongst the first group whilst James Hamilton, first earl of Arran and Hugh Montgomery, first earl of Eglinton, headed up the second. James Beaton, archbishop of St. Andrews, and Colin Campbell, third earl of Argyll were in the third group; and John Stewart, third earl of Lennox, William Graham, second earl of Montrose, Cuthbert Cunningham, third earl of Glencairn, and Robert, fifth lord Maxwell, led the fourth.2

The scheme fell apart as Angus simply failed to hand over the young king to Arran at the end of the first quarter, in effect executing a simple ‘coup d’état’.3 In June 1526 Angus moved to legitimise his position. It was declared in parliament that James was now fourteen years old and hence of an age to exercise his royal authority personally. Accordingly all prior delegations of such authority were annulled.4 The king had thus reached his ‘majority’ – technically responsible from there on for his own decisions, but actually controlled by Angus and a royal Household that shortly was to provide positions for Angus’ relatives. Angus’ brother, George Douglas of Pittendreich (Elgin) was appointed as carver to the king; their brother-in-law, James Douglas of Drumlanrig (Dumfries), became master of the wine cellar, and their kinsman, James Douglas of Parkhead (Lanark) was made master of the larder.5 These titles were largely meaningless; the significant point was that the king was under physical supervision of Angus’ own supporters.

Angus also secured the offices of state, taking the vacant Chancellorship for himself in 1527 (James Beaton having the previous year resigned office in outrage at Angus’ sabotage of his campaign to be promoted as Cardinal) and appointing his uncle, Archibald Douglas of Kilspindie (Perth) first as Treasurer and then also as keeper of the privy seal.6

Emond has argued that Angus’ coup d’état was not staged primarily as a bid for sole power at a time when the country lacked an adult king, but rather in an effort to preserve his own position as one of the lords of Scotland.7 Faction fighting was perhaps the principal feature of the minority of James V. Royal authority was intermittently exercised in the form of the governor, John, duke of Albany (first cousin once removed of the king). Albany’s third and final tour of duty in Scotland ended in May 1524. Control of government was then exercised by Margaret Tudor with the support of Arran. This was contested by Angus, supported by Lennox. The rotation scheme drawn up in parliament in 1525 reflected current divisions amongst the leading magnates. By holding on to the king’s person, Angus obtained not only legitimacy – the declaration of the king’s ‘majority’ in 1526 was a tactic which had been used in 1524 by Margaret’s supporters – but also protection. An attack on Angus could be interpreted as an attack on the king.8

The first challenge to Angus had come in January 1526 when there was a confrontation between Angus’ and Arran’s supporters near Linlithgow. Arran backed down. Later in the same year he lent his support to Angus.9 On 21 June 1526 a secret council was appointed in parliament to advise the king. Its members included Angus, Argyll, Lennox, Morton, Glencairn, Lord Maxwell and Gavin Dunbar, archbishop of Glasgow. Five days later James V obliged himself to Lennox to take the earl’s advice on all important occasions ‘fyrst and befor ony man’.10 The second challenge to Angus came in July 1526 with an attempt by Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch to abduct the king. The skirmish at Darnick, near Melrose, between the Scotts on the one hand and the Humes and Kerrs in Angus’ company on the other, resulted in the death of Andrew Kerr of Cessford.11 It is not clear whether or not Buccleuch at this point was acting in league with Lennox, but later in the same year he joined that earl in a fresh attempt to abduct the king. However, by this time not only had Lennox changed sides but so also had Arran. In September 1526 Lennox’s attack on the forces about the king at Linlithgow was beaten off and Lennox himself was killed. The official criminal record stated that the attack was made upon the earl of Arran’s supporters. Sir James Hamilton of Finnart was suspected of being Lennox’s killer. The contemporary chronicler, Adam Abell, interpreted the clash as being between Lennox and Angus. In the parliament of September 1528, a charge of treason was laid against Angus and his supporters for ‘. . . exponying of our soverane lord to battell he being of tendir age . . .’ on the fields of both Melrose and Linlithgow.12

For Emond the agreement reached between Lennox and James V on 26 June 1526 was the first unmistakable sign of the king showing an independence of action, not in accord with his custodians.13 Certainly, the intention in parliament was to have Angus, not Lennox, appointed as the chief counsellor of the king. The bond with Lennox was therefore made without Angus’ knowledge, and Emond has observed that it is significant as being the only bond made between James and an individual magnate, possibly indicative of his desperation to be free of the Douglases.14 However, it is equally possible that the initiative lay with Lennox, who had perhaps pretensions of staging his own coup d’état and thus aligning the royal cause with his own. The Lennox Stewarts were next in line to the throne after the Arran Hamiltons, and thus outranked the Angus Douglases. At Linlithgow, Arran and his ‘part-takers, there assembled for the preservation and defence of the king’s person’,15 might well have welcomed an opportunity to repulse Lennox and his supporters. The ward of the Lennox earldom was initially distributed equally between Angus and Arran.16

The failure of the Lennox abduction in September 1526 prompted Angus to strengthen his control of both Household and government. This in effect meant a narrower concentration of power, with Angus both unwilling either to trust or appeal to Lennox supporters and unable to maintain solidarity with Arran, who attended the sessions of the Lords of Council at Edinburgh on just two occasions after Linlithgow.17 Emond has argued that from that point onwards the failure of the Angus Douglas régime was inevitable, with the king only waiting for an opportunity to escape.18 In his interpretation the ‘failed policies’ of the Angus government rendered it ‘dispensable’ once the king and Angus were no longer ‘compatible’.19 This suggests that the king’s desire to escape from his Chancellor and his dissatisfaction with his Chancellor’s policies were not necessarily correlated. In fact, the opportunity to escape and the motive which lay behind it both originated in 1528; the rationale, that the king had been held against his will by the Douglases since Linlithgow, was not the central issue at stake.

One of the substantive charges brought against Angus, which his lawyer and Secretary, John Bellenden, had to answer in the first parliament held under the personal rule (September 1528), concerned an incident in the Borders. The charge was of:

. . . treasonable art and part of assistance and maintenance given to John Johnston of that ilk bound in service to Angus to harry and burn with company of thieves and evil doers diverse times by day and night in the month of June bipast corns, lands and lordships and houses in sheriffdoms of Annandale and Niddesdale, pertain to James in property and other diverse buildings lands and houses within said sheriffdoms. . . .20

The particular concern was with an attack made by Johnston on the royal lands of Duncow in Nithsdale. The underlying issue was that Angus was failing to give good government in the Borders.

Angus was warden of the East and Middle Marches from 15 March 1526 until July 1528.21 In the East March he succeeded Lennox who had been appointed in September 1524. The traditional wardens were the lords Hume; however the third lord had been executed for treason in 1516 and George, fourth lord Hume, at best acted as deputy-warden. In the Middle March Angus succeeded Andrew Kerr of Cessford, who acted as deputy until his death at Darnick. On the West March Lord Maxwell had acted as warden since 1515, and his suitability for this task – being the chief man of the area – was never seriously questioned by those in power, whether or not they were in agreement over other issues.

The Angus earldom embraced various border territories. In the east, in Berwickshire, Angus held the regality of Bunkle and Preston and the lands of Dye forest. In East Lothian was the lordship of Tantallon. Further south lay the barony of Selkirk and regality of Jedburgh-forest.22 To the south-west of these areas was Liddesdale. Formerly a possession of the earls of Angus, in the reign of James IV the lordship had been exchanged for the lordship of Kilmarnock, then a possession of the Hepburn earls of Bothwell.23 Patrick Hepburn, third earl of Bothwell, was of an age with James V and he was tutored by his great uncle, Patrick Hepburn, prior of St. Andrews, whilst his affairs were managed by his uncle, the Master of Hailes.24 Hailes was thus charged with giving good order for Liddesdale in 1518, and again in September 1527.25 However Angus took it upon himself to intervene in the pursuit of good government. In February 1526 he assumed responsibility for the area; in April and then again in June he led punitive expeditions against thieves.26

A punitive raid had also been directed against Hailes’ own house of Bolton in East Lothian in 1524, in the course of which the house was destroyed by fire. The raid was conducted by Angus, Lennox, Maxwell, Malcolm, third lord Fleming, and the Master of Glencairn or Kilmaurs. It was declared by act of parliament in June 1526 that this had been authorised by the king for the purpose of detaining rebels in Hailes’ company. Hailes was aggrieved; and in January 1529 he petitioned the Lords of Council that the terms of the declaration might be reduced in acknowledgement of the service that the Hepburns could offer the new administration. The lords agreed to look into the matter, but nothing further happened during James V’s reign; not until fourteen years later, in 1543, when Hailes made supplication to parliament that the 1526 ruling be revoked. If this were done then Hailes could pursue Angus through the civil courts for compensation for the destruction of Bolton. Hailes claimed that the late king had intended to revoke the act in his majority but was unable to do so because of the influence of enemies of the Hepburns.27 Interference in their border territory and burning their castle hardly endeared the earl of Angus to the Hepburns, and a further insult was the appointment in June 1526 of Comptroller Thomas Erskine of Haltoun as king’s Secretary in place of Patrick Hepburn, prior of St. Andrews.28

In the period of his domination of Scottish government, Angus assumed a large measure of responsibility for the keeping of good order in the Borders. As well as raids on Liddesdale and other Hepburn territory, in July 1526 he took the king with him to Peebles and Jedburgh, in order to hold justice ayres. The intention was apparently to proceed to Whithorn, but the itinerary was disrupted by Buccleuch’s attack.29 Angus had at least the co-operation of his deputies. Lord Hume, Andrew Kerr of Fernieherst, Mark Kerr of Littledean and Andrew Kerr in Littledean were all in November 1526 given thanks in parliament for their support of the king – and Angus – in resisting the attacks by first Buccleuch and then Lennox. In the same year they gave redress for their respective Marches, the Kerrs carrying out the duties on behalf of the young Walter Kerr of Cessford.30 Cessford himself was appointed as chief cupbearer in the Household in succession to the discredited Buccleuch.31 However this cooperation did not stretch far enough for Angus to maintain credibility as an effective controller of the Borders.