Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

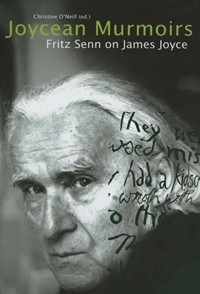

In charge of the Zurich James Joyce Foundation since its inception in 1985, Fritz Senn has studied the life and works of James Joyce for five decades, published widely and taught across Europe and the United States. He has been on the editorial board of all major Joyce journals, co-founded A Wake Newslitter with Clive Hart in the 1980s and supervised and co-ordinated the Frankfurt Joyce Edition with Klaus Reichert from 1969 to 1971. He has also instigated and co-organized several international Joyce Symposia. In Joycean Murmoirs, Christine O'Neill, a Zurich Joyce scholar based in Dublin, has drawn Senn out in numerous, wide-ranging interviews about Joyce and his works, the global Joyce community and friends, problems of translation, Joyce and Homer, the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, the intricacies of language and, not least, his own life and personality. These thought-provoking exchanges lend a privileged view of a richly eclectic literary and cultural milieu, giving glimpses of leading scholars and commentators from Richard Ellmann to Niall Montgomery and Anthony Burgess. They form a fascinating composite portrait of one of Europe's foremost international Joyceans.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 845

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHRISTINE O’NEILL (ED.)

JOYCEAN MURMOIRS

FRITZ SENN ON JAMES JOYCE

CONTENTS

Title Page

Illustrations

Preface by Fritz Senn

Preamble by Christine O’Neill

Acknowledgments

Beginnings

Reminiscences

One Thinks of Homer

Language/Translation

Procedures and Prejudices

Joyce’s Other Works

Odds Without Ends

Excessive Aversions

Annotation

Going ‘Mis’

Theoretically Yours

The Author Behind It All

Gender and its Discontents

Ochlokinetics

Some Martial Flurries

L’art d’être grandp…

Our Zurich James Joyce Foundation

Random Dramatis Personae

Guardedly Personal

A Belated Windfall

Books Mentioned

Index

Copyright

ILLUSTRATIONS

Photographs between pages 178 and 179

Frank Budgen, Fritz Senn and unidentified

Maria Jolas

Carola Giedion-Wecker

Fritz Senn and May Monaghan

Harry Levin

Marvin Magalaner

Thornton Wilder

Heinrich Straumann

James Atherton

Adaline Glasheen

Richard Ellmann

Richard M. Kain

Hugh Kenner

Maurice Beebe

Bernard Benstock

Thomas E. Connolly

Jack P. Dalton

Ruth van Phul

Nathan Halper

Florence Walzl

Mabel Worthington

Norman Silverstein

Margaret Solomon

Father Robert Boyle SJ

Robert Day

John Garvin

Niall Montgomery

John Ryan

Ulrich Schneider

Gerardine Franken

Leo Knuth

Macjei Słomczynski

Jacques Lacan

Wolfgang Hildesheimer

Saul Bellow

Fritz Senn © Christian Scholz, Zurich

PREFACE

FRITZ SENN

So once more a book that I have not really written comes out under my name. In fact I am both ambivalent subject and self-conscious object. Once more it is the outcome of someone else’s initiative.

The origin is in all those stories about long ago that were and are still exchanged in the evenings, usually during a Joyce conference, about the ancestors of the Joyce family — I mean the family of Joyceans — many of whom are no longer with us. The times before you youngsters were around. Meanwhile I have become even more of a Nestor, a commentator on far-gone days and events. Memories have accumulated over half a century and have no doubt changed in the process. Stories tend to take on a life of their own and become almost fixed in their formulation so that they, quite possibly, occult the original events. That, incidentally, is History — not so much what actually happened, but what someone remembered and passed on. At any rate, from time to time a listener, possibly out of politeness, proposed to have it all written down. This was never a viable option for me. I know myself too well: while I am struggling to put an incident into coherent prose, other reminiscences crowd in and have to be put aside for future use but most likely then fade into oblivion. I also find that, so different from a telling in inspiring company, as soon as I fix something verbally it becomes lifeless, no matter how fanciful the original anecdote may have been.

That’s where Christine O’Neill comes in. And that’s a long story. She had drifted into a Joyce seminar I did for the University of Zurich in the anniversary year of 1982, and she volunteered to present a paper at very short notice. It had to do with translation, and she emerged with credit. Two years later, when she went to Trinity College, Dublin for a year, I was able to give her a few propitious contacts, among them my old friend Niall Montgomery and also Petr Škrabánek. After her return we remained in touch. When the Zurich James Joyce Foundation (ZJJF) opened, we employed her part-time for the next few years to help in the day-to-day running of the establishment. She came to use our research facilities extensively, in particular when she did her doctorate at Zurich University under the direction of Professor Andreas Fischer (who was not yet a member of our board of trustees) and my less official self. Her choice to focus on the ‘Eumaeus’ episode may have had something to do with my own predilection.

In our weekly Ulysses reading group in the mid-eighties she came across a visiting Irishman, Tim O’Neill. He showed a lively interest and contributed many insights thanks to his comprehensive knowledge of manuscripts and Irish history. His interest — not that I noticed for a long time — was not limited to our reading of Ulysses. In due course Christine Bernhard became Christine O’Neill and finally settled in Dublin. For years the O’Neills have been a kind of Foundation outpost and have excavated an amount of relevant material that is now part of our holdings. It was Christine O’Neill who collected some of my essays and edited them for what became Inductive Scrutinies: Focus on Joyce in 1995. More recently, she resourcefully initiated the present project. With determination, she proposed the idea to Antony Farrell of The Lilliput Press, as well as to the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, and with untiring resolution descended on the Foundation at irregular intervals. She corralled me and set to it, microphone and notebook at the ready. On occasion the interviews were continued in Dublin. All along the way I had to be prodded. My enthusiasm for the project was intermittent. I often found myself procrastinating, indisposed and reluctant, especially when it came to dealing with her very faithful transcripts. From any given question or cue I could hardly restrict myself to the subject at hand but soon trailed off, associated freely and got bogged down in side issues. I often had to be called back to the topic at hand. All of which was part of the idea, or, at least, an inherent risk.

In Act Two all the accumulated clutter had to be reworked into coherent sentences. It is excruciating to read what one has said spontaneously even when it sounded crystal clear at the moment of utterance. Then I found how much I had been repeating myself and how much I had left out. Next, some semblance of structure had to be imposed on the haphazard jumble of reminiscences. So the result, predictably, is a bit of a hybrid. Based on the interviews and transcripts, it had to be edited and filtered (syntactically), and many dates and references had to be checked. During all that time new memories cropped up and adaptations were necessary. All of this will no doubt show in the multiform retrospective arrangement. The impetus was Ithacan, with its question-and-answer procedure, but the result possibly comes all too close to the uneasy amalgamation of ‘Eumaeus’. Despite considerable reworking, there remains something of the as-you-go-along nature of the original interviews. So this is also an untastable apology for the chaosmos of it all. Or, to wind up all the caveats, whenever something appears to lack coherence, let us put it down to spontaneity.

So I owe it all to Christine and her perseverance — encouragement, cajolery, coercion, scourges, thumbscrews, blackmail, forbearance and whatever else she astutely had at her disposal. The advantage for me is that I can evade responsibility and blame the topics and selection on her questions. She, in turn, might rejoin that I had both time and opportunity for ample modifications which, of course, I had. I am good at putting things off, so the months went by while she was breathing down my neck.

There is nothing remotely complete about these chancy memoirs. Nor is there much justice in the space allotted to colleagues, Joyceans, friends and others in these pages. Some get scant mention or none at all, partly due to limitations of space, more often due to inadvertence and flawed memory. The emphasis is on the earlier times as there is no way of keeping up with all the contacts of more recent years. At the moment I have twenty symposia under my belt and an even greater number of conferences in many countries and three continents. I have just calculated that since 1985 I must have had contact with at least 120 different participants at our annual workshops alone. In a few rare cases, incidentally, it may be an advantage not to be mentioned. Omissions abound, and a few complaints have already reached me before publication.

Inevitably there has been a great deal of self-restraint, or call it internal censorship. Above all, I do not aim to intrude into the private or personal, not even in my own case. For better or worse, some of the more racy anecdotes remain the stuff of oral poetry, more appropriate in an intimate circle or at a late-night session in an Irish pub (where usually I cannot even hear what anyone is saying). What one remembers is often funny at the expense of an otherwise perfectly personable victim. By their nature, the more ludicrous events are more entertaining than straight admiration can ever be, as the narrator of the ‘Cyclops’ episode demonstrates so vigorously. I would not follow in his eloquent footsteps even if I had the skill. So there is at best, or is it worst, only muted scandal. It must be human nature that the less agreeable encounters loom larger in memory than many good and stalwart acts of friendship. This explains why some of the more colourful or wayward individuals that have crossed my path of old have come in for more limelight than many of those that are more like you and me. So the best friends may get undeserved short shrift.

Still, a less than Christian impulse could not be entirely repressed. There are a few particularly fatuous statements that I did not have the heart to leave out, but their perpetrators will remain nameless. Had I foreseen at the time that decades later I would be subjected to a ruthless inquisition, I might have taken notes on many occasions when I asked diffident questions of some of Joyce’s contemporaries.

Emphatically, this is neither an autobiography nor a history of Joyce criticism nor a panorama of Joycean activities. As usual, I cannot ever avoid going back to the Joycean texts on the slightest provocation, but since this is not an academic study it lacks all scholarly paraphernalia and appends only a list of books that have been referred to in passing, and an index where you can see if you are listed. Chances are you are not. My overall aim was to show how so much of what is now the Joyce Industry or mafia is not some powerful behind-the-scenes fraternity pulling strings. Rather it is something that grew initially from the personal enthusiasm of individuals who did not, at first, have academic promotion as their goal. I have tried to describe this from my own subjective angle.

The reminiscences are larded with all sorts of opinions, prejudices, grievances and views on Joyce, including some unsolicited by Christine. All the codology of the Joycean business is destined for a small, inside audience mainly, those, in other words, to whom names like Frank Budgen or Richard Ellmann, or terms like ‘Epiphany’, do not have to be explained. For those entirely outside, it may grant insights into the sociology of professors of literature, amateurs, or just enthusiastic readers, and the rituals they give rise to. Possibly this haphazard chronicle may help to define such a vague and precise term as ‘Joycean’. At an early stage Rosa Maria Bosinelli in Forlì, Italy, gave valuable advice. Parts of the earlier rough typescript were subjected to the scrutiny of Katie Brown, Ruth Frehner and Sabrina Alonso. Ron Ewart of the Zurich Finnegans Wake reading group and Tim O’Neill in Dublin proofread the manuscript in its entirety. I am grateful to them all.

PREAMBLE

CHRISTINE O’NEILL

Joycean Murmoirs collects Fritz Senn’s memories as a Joycean and conveys his experiences, attitudes, prejudices and opinions. The book recounts some of the early activities on the Joyce scene and marks his place in a lively and still growing community. It portrays his involvement, endeavours and limitations. Aimed primarily at a Joycean audience, Joycean Murmoirs hopes to fill gaps and trigger memories. It is, however, neither a systematic biography nor a scholarly history of a developing academic industry.

Wooden phrases and tedious comprehensiveness are anathema to Fritz Senn. Ill at ease with formality, he favours responding and engaging; hence Joycean Murmoirs is based on interviews. Instinctively judicious, he realized that, having someone else ask the questions in discussion, he could abdicate responsibility while remaining free to raise any topic he wanted.

In one of Chesterton’s stories, Father Brown observes that people hardly ever answer the questions put to them, but at best respond to what they imagine was put to them. This is worth keeping in mind while reading a book based on interviews, when the vagaries of associative memory may have come into play. At the outset, Senn promised to tell the truth or else to say nothing, which, of course, didn’t preclude an occasional ‘very muted version, full of coy omissions’. It is fair to say that he clammed up only a few times, and probably not simply because of the recording device in front of him. Generally, the interviews ran smoothly in a relaxed atmosphere, and, due to the eminently verbal nature of his memory, he formulated his answers and comments with remarkable precision.

Once the recordings were transcribed, the script was given back to him to work on. As we edited the text together, fashioning the material into related topics, Fritz, thinking of Joyce and Homer, often wished for some corresponding grid to give his outpourings some congruent shape. An air of ad hoc reminiscence and randomness remains, as well as some unavoidable overlaps (see a parenthetical ‘my rant occurs elsewhere’) as we made no attempt to contrive a unified story line. We did, however, delve into his private photographic archive to scatter portraits generously throughout the finishedtext. The visual images bring alive his era of Joyce scholarship (though the prime criterion for inclusion was that the subject was dead).

There were many names I wanted to spring on him apart from those arising in our conversations. Needless to say he talked about more Joyceans than are assembled in this book, some of them close friends. However, there didn’t seem much point in recording names unless there was some tale to tell. Friendly relationships don’t always make for good stories, not even in a memoir. We agreed that the memoirs had to be tactful, and so, a considerable body of fine stories is destined to remain oral poetry. Similarly, a few opinions, recollections and anecdotes had to be toned down, to avoid causing offence. As with any biographical writing, some echo chambers had to be kept closed. Inevitably, there are people, events and pictures that ought to have been included but were left out or have been treated inadequately. We apologize for such omissions and shortcomings.

Newspaper profiles of Fritz Senn of the past forty years are boringly consistent. Our subject is depicted as a tall, lithe figure with a fine mane of silvery hair in later years, agile, swift, a fleeting shadow; a distinguished, enthusiastic expert on Joyce. Regarded by many as Joyce’s ideal reader, this non-academic individual is an unpretentious scholar who found Joyce’s works a welcome distraction from his own sombre moods.

These descriptions fit the character, and they concur because Fritz Senn is remarkably controlled and self-aware. If Joyce’s texts are ‘hyper’, as he puts it, so is he, in many ways, and so are his writings: hyper-sensitive and hyper-precise. Should he contradict himself, he’s the first to be aware of it; he is drawn in only when he wants to be drawn in. Although he thrives in company, he ‘never gianed in with the shout-most shoviality’. The man is fiercely private and independent.

Haines’ ‘I don’t know, I’m sure’, might summarize his attitude. His survival instincts are honed; he moves like a cat and may not be manoeuvred into a corner. He keeps moving. It is no surprise that the protean Joycean texts and the all-pervasive themes of misinformation and failed communication should strike resonant chords with him, as does Joyce’s empathy with human loneliness. The Wake’s ‘pollysigh patrolman Seekersenn’ has found a Swiss embodiment.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to Fritz Senn, first and foremost, not only for his willingness to co-operate in this project but for two decades of sharing knowledge, time and friends. I am grateful to Anne Fogarty who sparked the idea for such a book and indebted to Richard Brown, Jean-Michel Rabaté and John Paul Riquelme for communicating critical views of Fritz Senn; to Rosa Maria Bosinelli, Geert Lernout and Katrin van Herbruggen for reading the manuscript at a very early stage and making valuable suggestions; to Vivien Veale Igoe for allowing me access to archival material concerning the early symposia; and to the board of the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, especially Verena Füllemann, for prompt and enthusiastic support. Ron Ewart and Timothy O’Neill read and commented on the final draft. Thanks are due to them, and to Fiona Dunne for her careful editorial work. Thanks are also due to Antony Farrell of The Lilliput Press for his interest in the project from the outset. Special thanks to the late Katharina Ernst, a gracious hostess in Zurich on many occasions, and to Timothy, Brendan and Niamh O’Neill for giving me time and space to work.

BEGINNINGS

What would you say is the motivation behind your unique involvement with Joyce?

Motivation is what moves us, and I do not think I will ever know. But I never had any doubt that my preoccupation with Joyce — and I always mean the works and far less the author — is a substitute (or ‘Ersatz’) for a satisfactory life or the kind of success one dreams of in adolescence and can never stop desiring. Maybe a term like ‘sublimation’ comes close to it.

It sounds more like disappointment.

If I needed a label for what must have been most on my mind, or psyche, it is frustration, which was all-pervasive. And you see me, philologist at heart, diverge right away into the word itself. It derives from Latin frustra, in vain — as good a summary of life as anything, and revealingly, the noun that did not exist in German when I first knew it, now does. Within decades the foreign adaptation has even reached a colloquial level, it has been shortened to a simple ‘Frust’ and can easily be paired with its opposite: Lust. There must be a need for it. The lack of emotional and, in particular, amatory fulfilment was probably more common in my, still very much inhibited, generation, and I was very shy when I grew up. I can’t recall a time when I didn’t think of failure; the 1950s particularly were a bad time.

Given such a feeling of deprivation, to absorb myself in reading Joyce seemed the next best thing within reach. If I had had a remotely satisfactory life you would not be asking me these questions. In all probability I would have ended up in Joyce, though hardly with a similar fixation. One has to cling to something, I imagine. If you asked me why I relate to Joyce — you did not as yet, but you may come near it or simply be too tactful to do so — I sense that his works show a great empathy with human failure. They are in many ways, whatever else, about just that. Along with Eveline, Little Chandler, Bloom, Gerty MacDowell, there goes Fritz Senn.

Did you ever seek help?

I had a short spell of psychoanalysis in the sixties which did little to improve the situation. One effect was that I lost an earlier interest I had had in psychoanalysis. What remains is my analyst’s remark of long ago in relation to a perpetual lack of self-confidence. ‘Let others decide about the value of what you do or achieve,’ he said, ‘you can never believe in it anyway.’ (Not that one can ever stop doubting it.) However, I found out, and pass it on as caustic advice to other battered psyches, that momentary self-assurance, once it emerges as a result of a momentary achievement, cannot be put into an account for future retrieval when needed. In our human situation, ‘miseries’ are heaped upon us, and the best we can do is to ‘entwine our arts with laughters low’, as the Wake poignantly puts it. I know there is a depressive strain in many fellow Joyceans, which may be why we adhere to whatever comic relief can be found. We seem to need some drugs, and interacting with a text is better than many others. If Joyce is the anodyne, the side effects are relatively innocuous.

Do you find that substitute satisfactions are also a theme in Joyce?

Bloom engages in a futile correspondence to get some thrills. Escapism with transient illusions infuse, in particular, the ‘Nausicaa’ episode. Bloom and Gerty MacDowell indulge in wishful thinking or in substitute satisfactions, and so do all those characters who find momentary solace in drinking or boasting, or the chimera of a change of location like exile. I wish I could look down on such short-range illusions from Olympian or scholarly heights, but I see myself uncomfortably mirrored. Reading may well be another form of escapism; it need not be Gerty’s cheap fiction, it can be Stephen’s concern with heresiarchs or our involvement with Joyce. So, for all I know, may be our conferences or workshops. For escapism, in other words, I would mount the barricades.

An underlying principle may be heralded already in Bloom’s pork kidney, which has risen to almost global fame in its Bloomsday 2004 coverage. We almost overlook that what Bloom liked best was grilled mutton kidneys, but that he had to settle for the second best — and he still enjoyed it.

There must have been more than textual satisfactions?

Joyce was not only a welcome and necessary distraction. There were plenty of side benefits, human ones that led to many contacts. The Old Joycean Boys Network (which includes a lot of younger female members and students) has never been a really potent network. It contains many friendships and relatively few enmities. We are almost too friendly, perhaps, and uncritically approving of each other. This becomes a handicap when we assess each others’ work in public. Does this get the confessional psychology out of the way?

Do you tend to see things happening by chance, as often as not?

I often marvel at the chancy nature of events, how, to borrow a phrase, a small event, trivial in itself, can change the whole course of a life. Plans are often futile. Bloom in Ulysses plans to attend a funeral and to take care of hisadvertisement, and he seems to have intended to see a play in the evening. But things take a different turn; meeting Mrs Breen makes him think of looking into the Maternity Hospital to enquire after Mrs Purefoy. If he had not turned up there, he would not have run into Stephen and ended up in Nighttown, not a habitual haunt. At the funeral, he was enlisted to help the Dignam family, which brought him to Barney Kiernan’s pub and to Sandymount strand and its voyeuristic gratification. So most of the later episodes hang on accidental occurrences. Coincidences of this kind also brought me to Joyce and, in the end, led to our Joyce Foundation. I call the workings of fate ‘Tychomatics’ and will no doubt expound on that later. Tyche is Greek for ‘fate’ and seems to hint at a governing hit-or-miss procedure.

Talking of chance, of accidents: how reliable do you think memories are?

I once had an excellent memory about certain matters. I knew what had happened when. Up to recently, I often teased someone, asking ‘What did you do this day seventeen years ago?’ Often I did know. I can still recall, no miracle, what I did on most Bloomsdays within the last thirty years or so. Yet the skill is rapidly fading.

Memory, a triumph and a hazard, is a central concern for Joyce and for all of us. All history, and what we think we know, is based on its shaky foundations. In Ulysses Joyce gives us the memories of characters, of a city, a country, a tradition and so on. It is also defective, chancy, quirky. In one way Finnegans Wake is also a gigantic, amorphous heap of memory fragments with a seemingly universal, but still highly Eurocentric, scope. But there is nothing to rely on. If there is an Archimedean lever we are still looking for it. Reading the Wake is bringing our own chancy memories to bear upon its riddles. ‘Ah, here I recognize St Patrick, about whom I once read something’ — that’s how we proceed.

We do not need Joyce to tell us that memory is not to be trusted. But he demonstrates how the mind selects, assimilates, changes and adapts, according to impulses we are not aware of. And it remains miraculous what exactly, out of all the welter of experience, the mind retains and twists, or why so many trifles are carried along. Ulysses is difficult to follow in certain early passages because the trivia fuse with momentous and crucial echoes in an outwardly random manner. Stephen Dedalus asks himself which events are remembered and recorded and thereby become history, and which ones are not.

Human beings and Joyce’s characters continually forget or misremember. One of the highlights of Bloom’s career is an encounter with the great Parnell that he recalls with pride, and he does so twice. Did the great leader say ‘Thank you’ to Bloom or ‘Thank you, sir’? Or is the appended ‘sir’ merely put in by Bloom for better effect? Finnegans Wake is an orgy of memories gone astray. Which of the many rumours about what Earwicker did in the Phoenix Park comes closest to what happened, if anything did happen?

How about your own powers of memory?

Of course, these truisms lead up to my questioning myself about how accurately I remember what I am revealing here. I am conscious that I often do not really and accurately recall all those events that have become stories, what I do remember are those stories. Many have frozen into an almost set form of expression. This needs to be said by way of caution for what is to follow. Unfortunately, I never took notes at the time and never kept a diary. I wish I had written down some of what Budgen or Maria Jolas said on certain occasions. Maria Jolas once described to Shari Benstock and me in detail just how exacting it was to deal with Lucia Joyce and her erratic, menacing conduct. But I have forgotten the drastic details themselves and only remember that it was Sunday morning, St Patrick’s Day 1974, the year the Paris symposium was in the offing. And, just to show the vagaries of memory, irrespective of significance, I remember that Maria Jolas two days earlier had attended a meeting in Paris that campaigned for the impeachment of Richard Nixon.

You once mentioned a flawed childhood memory of a picture from the Divina Commedia.

Indeed, I came to question my powers of memory more than half a century ago. In the thirties my grandfather in southern Germany had a book with illustrations, which showed hell with devils who tortured the damned with three-pronged forks, like tridents (not that I knew the word at the time). This one specific detail was engraved in my mind for years and still is. It must have been the Divina Commedia. Some ten years later, after the war, I found that particular copy in my late grandfather’s library; there were many illustrations in it, but no pronged forks. My mind had superimposed them from somewhere else. It taught me a lesson. Though I do my hardest to call up what happened to me, or what was said to me, I am sure my murmoirs here will contain their share of such transpositions, and I will complain about those of others that have affected me.

Go on a little, if you would, about the ‘chanciness’ of memory: after all, it’s central to what we’re doing.

I wonder what it is we do remember, and why. And what goes along the highway to oblivion, and what is transformed along the road. Many of us have the experience of being reported or quoted. The result is disillusioning. At best, when things are slightly twisted, perhaps only in tone, one feels ridiculous. Sometimes they are turned around completely. One example that lingers is something that was written in Die Zeit, a prestigious German weekly, about the 1982 symposium, where I was reported to have said that, in earlier times, we, the Joyceans, were ‘a happy family’. I cannot imagine myself ever using such a phrase with a straight face: it is not in my vocabulary. Yet I can reconstruct what must have happened. It was late one night in a pub where old and racy stories were retailed (a few of which will find their gossipy way into my tales here), and I know that I must have thrown out casually, and with jocular exaggeration, that we, the Joyceans, are like a big family where everyone has something nasty to say about everybody else. I am sure the journalist did not mean any harm but relied on his impressions when he made me a maudlin apostle of the good old harmonious family. It is mildly annoying.

My point here is that I am not immune to this sort of misappropriation. Some participants in the 1975 Paris symposium sensed a predominantly hostile atmosphere, but my impressions were quite different. Perhaps I was in the wrong place, but the symposium was a huge conglomerate of events, and no single witness could possibly survey the whole scene. I won’t be offering anything like whole scenes here in these recollections. Subjectivity and limited perspective are taken for granted.

The wholly unoriginal upshot is that memory is a process that transmits and modifies according to rules we don’t know, and not so much a body of fixed items, or a set of files that can be consulted. It is, to repeat myself, one of Joyce’s thematic concerns. John Raleigh discovered this when he set out to align Bloom’s jumbled memories in neat order. He had a hard time straightening them out in his Chronicle of Leopold and Molly Bloom. When I was consulted, I was just as puzzled and found that an accurate sequence of events cannot be extracted beyond doubt, just as we can hardly lay out the causality of Father Flynn’s decline in ‘The Sisters’. Joyce often echoes the question, ‘Is that a fact?’, which at times is simply an acknowledgment that one has listened to a story. But it is an insidious and pertinent question. We once discussed some of the innumerable aspects of memory and its Joycean repercussions in one of our Zurich workshops.

One rarely sees you at Joycean events without your camera. Is this pursuit of yours to do with a need to gather mementos?

Pictures trigger reminiscences. By definition, photographs write down scenes and events. Somehow I became a kind of pictorial chronicler of Joyce events and Joyceans (there must be more than two thousand items by now), but this was a side product of discovering a new medium. To me, it is still a miracle which, of course, technology can abundantly explain, that a scene can be optically retained, that light can be written and thereby preserved. Getting a real camera was an important step. It must have been in the late sixties or early seventies when, I think, on my first trip to the States, my father’s Instamatic couldn’t capture those huge majestic bridges and skyscrapers of New York, I decided I wanted something better.

The camera was my only access to what one might call creativity. If I had any creative urge it’s buried under thick layers of concrete and inhibitions. Taking photographs was another way of looking at the world, and one involving time: the present moment is preserved for a future in which the event has become past. The 1971 symposium in Trieste was the first place I put it to use, and I think a first batch of Joyceans was published in the James Joyce Quarterly (JJQ). I also found out very soon that the kind of pictures I took were always stereotypes, imitations of what I had seen, motifs like a fence or a leaf. So I soon gave up any budding artistic ambitions and contended myself with just taking snapshots. Pictures, artistic or not, at least are something concrete that can be shown.

Taking pictures is an anodyne and a substitute. I’m very kinetically nervous: you hardly see me in the same place for long. At parties, I am a dedicated circulator. When I wait for a bus or tram, I walk up and down, or when sitting at a meal I play with breadcrumbs. Other people smoke; I fiddle with a camera. This results in visual memoirs, whereas the side effects of smoking are potentially more harmful. Picture-taking is a way to pass the time, to move around or, in some situations, a polite excuse to leave a group and join another one in a far corner where I hope the action really is. (It is never in that other place, either.) The camera satisfies a kind of voyeuristic instinct. It does so, ideally. Taking pictures, at least, is better than getting nowhere. I have outlined already that I believe in substitutes.

What was your earliest introduction to Joyce?

For better or worse, I never had the training or support of a university, simply because there was no such thing as Joyce studies in Zurich when I was a student. I was not really qualified in the first place. My English is what I learned at school, an acquired language. I knew next to nothing about Ireland except that it was somewhere beyond England, and, though formally baptized a Catholic, I was never exposed to the teachings of the Church and belong to none now, hence I lack an essential prerequisite.

My first encounter with the name James Joyce was in a small history of English literature of 1930 where he was given a brief mention: Ulysses was ‘an obscene, squalid, in parts brilliant, in parts tedious study of the slums of Dublin’, a ‘cynical allegory on the story of Odysseus and Penelope’. Though the book clearly stated Dublin as the location, I dimly thought for a long time it was Edinburgh (so much for memory). On a wall of the very small English Department of the university hung a picture by Wilhelm Gimmi, the Swiss painter. It showed a man of unpleasing appearance with an eye patch. The painting, by the way, is now in our Foundation on loan. That, I was told, was James Joyce. It was my first visual impression.

Professor Heinrich Straumann played a crucial role, didn’t he?

Yes, it was he who introduced us to Joyce. A very bright young student in a ‘proseminar’ had presented ‘The Dead’ in a paper, and the professor took up the theme and told us about his meeting with Joyce. When he heard of Joyce arriving in Zurich in late 1940 he went to see and interview him and so became the last important witness. He gave us his impression of Joyce as he had seen him, weeks before his death, and he briefly sketched Joyce’s impact on literature. It inspired me enough to get hold of Dubliners, and I diligently read the stories, but they did not then affect me in any particular way. They seemed a bit unsubstantial and, very often, came to an end when I turned the page: there was no surprise or clinching ending. A bit anaemic they looked, at the first go.

If it hadn’t been for Heinrich Straumann, however, I might never have taken up Ulysses in England in the autumn of 1951 and would not now be talking about what happened as a consequence. More about this later. After I had left, I still kept in touch with Straumann, and we were together on many occasions.

One time, it happened to be exactly the twentieth anniversary of Joyce’s death, 13 January 1961, we went up to Joyce’s grave with Richard Ellmann. We met again at the unveiling of the Joyce statue in 1966, and when Joseph Strick’s Ulysses film was launched, we both said a few words to the press. There is even a booklet with his and my short memorial addresses given in the aula of the university on 2 February 1982. Incidentally I had first seenProfessor Straumann escorting Winston Churchill, who, in the selfsame aula, delivered his famous speech about the need for France and Germany to forget their old grievances. The students of the local high schools, including me, lined the streets to wave at the illustrious visitor.

Heinrich Straumann was one of the professors who still did survey courses. The outlines he provided have served me well ever since. His dissertation topic seems very much advanced even now: he had investigated the development of newspaper headlines in the twentieth century. In ‘Aeolus’, independently, Joyce had more or less done the same. Straumann may well have been the first European scholar, at least in German-speaking countries, to concern himself with modern American literature. He took a continued interest in Joyce and later also in our Foundation, and he attended most of our events or else, rather touchingly, excused himself when he couldn’t.

In the two decades after the war, the English Department was fairly small and fitted conveniently into two library rooms. In the thirties the chair of English Literature had been held by Bernhard Fehr, who had been in contact with Joyce. In fact, Joyce asked in letters who would become his successor. It was Heinrich Straumann. I completely forget who told me of an occasion where Joyce and Professor Fehr were together in a local pub, though we call it a ‘restaurant’ even if you only go for a drink. From what was reported, Joyce never talked literature, but only music. And the story goes that the two were singing Italian opera arias at each other, in mounting enthusiasm, even jumping on tables, though the latter detail is probably an embellishment.

Another professor who was familiar with Joyce’s works and who, for a time, took a protective interest in me, was Max Wildi, whose lectures were highly inspiring. In fact he tried to encourage me to go back to university and leave with a degree. He was the first to refer to me in one of his talks on Joyce, and I was proud to have a passing mention in a newspaper report on that talk, but, in the nature of things, my name was confused with that of a minor Swiss writer, Fritz Senft. I sympathized with L. Boom.

While on the subject of local boasting, the first invitation to talk in front of a class came from a colleague of Heinrich Straumann’s, Hans Häusermann in Geneva, also a former student of Bernhard Fehr’s. He had seen a few articles on Finnegans Wake I had written for newspapers and asked me to speak to his Joyce seminar. This led to my first bow to a small academic public. It must have been in the early sixties. It shows my nervousness at the idea of speaking in front of a class that I went to Geneva one week earlier just to check out the conditions and the size of the room to allay my apprehension. Of course I then had a carefully prepared script and hardly looked at the audience to verify how they took it all.

Was it while spending a year in England that you turned to Ulysses?

It was a sensible requirement for a student of English to spend a year in a country where you could learn the language, and at that time this automatically meant England. It brought me to Hampton Grammar School as an exchange student in 1951–2 where I was to teach German conversation for £24 a month. The pay did not allow me to travel and explore the country. So I decided to have a go at that author who was, after all, connected with Zurich. I bought a Bodley Head Ulysses in a department store in Kingston for one guinea and also, since it was on a shelf nearby, Partridge’s Dictionary of Slang, a good investment as it turned out. How exactly I dabbled and tried to cope with the book, I cannot remember. I do know I looked up ‘parapet’, which was in a dictionary, and ‘gunrest’, which was not. I probably skipped over ‘Chrysostomos’. Yet I must have persevered. I also experienced one of the last typical London fogs where you could hardly see your own hand stretched out, a bit like reading a dense paragraph in Finnegans Wake. I struggled bravely. There was not even a good dictionary to hand. I now wonder what exactly I could take in as I groped for my way through the book.

My English wasn’t adequate, nor did Ulysses live up to its alleged promise of enticing obscenity. After a few months I borrowed Stuart Gilbert’s study from a local library, and it put inchoative understanding on a more solid basis. The book was an eye-opener for me. I have not forgotten the one sentence that made me click. Gilbert discusses a passage from ‘Sirens’ in interior monologue (‘Tenors get women by the score’) and points out that ‘score’ is also a musical term. I, staunch unbeliever in epiphany, experienced something like a revelation.

Somehow this semantic overlay tipped me over, the subsidiary implication affected me so much that I still remember the trivial gloss. Typically it was a formal element that excited me, something to do with language. Or was it? That there is an obvious undercurrent of sexual envy dawned on me only much later. I have since become quite aware that for many of us, textual intercourse is a substitute for the real thing. I do not mean the erotic passages, which for me generally have an odd and somewhat unpleasant taste in Joyce. The substitute is in the wrestling with a text that withholds and teases and reveals and seduces. It is textual copulation.

Did you get to Dublin at that time?

As I wanted to see Dublin I took a weekend excursion train from Euston for 70 shillings, leaving Friday night and arriving at Dun Laoghaire at 7 am the following morning, to return at 7 pm the same day. My first day in Dublin was 2 May 1952, the Saturday when Newcastle beat Arsenal in the Cup Final. It was a long journey, and the crossing took about four hours; the boat was full of euphoric Irishmen singing, dancing and boozing on board, stamping their feet with annoying stamina — probably an appropriate introduction to the country. It was a drizzly day, and I inspected a great part of the city. A Frenchman of my age who was teaching conversation at the same grammar school came along and must have been excruciatingly bored being dragged to look at odd buildings.

Oddly enough, my memory of the actual city blends with what I had gathered from the book and with later visits. I remember that the quays were rundown but that there was an Elephant House with an elephant still on show. We went to look at 7 Eccles Street, which was then still inhabited. Only a few months into the book, and hardly halfway through, I must have known where Bloom lived, probably from Gilbert, for I had not yet figured it out for myself. In fact, few readers do. We went to the Phoenix Park and climbed a low tree. We seem to have covered a lot of ground for we also made it as far as the Martello Tower in Sandymount. I already knew it was not the right one much further south, but still a genuine replica of identical shape.

Whatever else I forget, I do remember a toilet in a restaurant in O’Connell Street that was so incredibly dirty that even the one in Westland Row railway station was preferable for two travellers in need. So much for memory and what it retains. Dublin did look drab and uninviting, but I was looking at the urban simulacrum of a book I had not even finished reading at the time, and certainly did not understand. Naturally I had also acquired a map.

How did your interest in Joyce develop from there?

I had reached only midway in Ulysses when I graduated to Finnegans Wake. I believe it cost 32 shillings, more than 15 per cent of a month’s salary. But I did not read very far. Back in Zurich I continued with my hobby, Ulysses, and soon began to dabble in the Wake and lost myself in it. But before long things changed drastically when Life struck. A child was on the way, I got married and had to support the new family with a bread-and-butter job as a proofreader. So I never finished my studies that had dragged on aimlessly anyway and with little purpose. A dark period set in that I will not depict at any length; I try to block it out. For years it looked as if there was not much of a future, nothing worth making an effort for. Joyce was relegated to a hobby, but an abiding one that somehow got me through intermittently depressive times. Possibly the Wake was the best distraction in such a plight. It absorbed me, and I went through it, slowly, word by word, with the help of dictionaries and, later on, with the current Encyclopaedia Britannica. I took heaps of notes that just consisted of what I could grab from reference works.

It was a sort of indiscriminate poking around in the text and clutching at straws without ever arriving at a coherent structure. There was little help apart from the annoying Skeleton Key — annoying because it often just quoted long passages instead of explaining them. Harry Levin’s study was pertinent and perceptive but fairly general and gave little practical help. I briefly encountered Harry Levin much later, when giving a talk at Harvard in 1975, and we exchanged a few words. John Kelleher, the expert on matters Irish at Harvard, was also there. It was rewarding to meet the masters in person, no matter how briefly.

Our municipal library, the Zentralbibliothek, patronized by Joyce more than thirty years earlier, closed at 7 pm and was not accessible for someone with a fortyeight-hour working week. That meant that I avidly looked around for help and acquired what few books were then appearing on Joyce. I scanned the horizon as the few publications came out slowly and at great intervals, and I even joined the Modern Language Association of America (MLA) and subscribed to its journal, just for the ads of new publications.

A decisive step was when I wrote to James Atherton. He had written a few articles on Finnegans Wake, and I chanced a letter to enquire where his articles could be obtained. The letter found him in a place called Wigan, Lancashire, and a fertile correspondence was initiated. I will come back to Atherton, my mentor, who sent me his pioneering essays and got me in touch with Adaline Glasheen in Farmington, Connecticut. One of the greatest letter-writers ever, she, in turn, had been exchanging glosses on Finnegans Wake with Thornton Wilder. This way an epistolary network originated and spread: it was joined by Clive Hart, then a student at Cambridge, who was putting together a concordance of Finnegans Wake, by Bernard Benstock and many others. There was vibrant excitement of the kind that still affects new readers anywhere on the globe, and before long, we started to bundle the glosses in the venture of A Wake Newslitter, which Clive Hart and I had set in motion. The main motor and driving force, I emphasize, was Clive, as I had my slumps of inertia.

Why was James Atherton so important for you?

He was the one who turned me from a reader and consumer of Joyce into someone who churned out comments, an active contributor to critical pollution. Naturally, it might have happened anyhow, given my own explorative compulsion. When Atherton replied to my letter, he suggested that I first look into references to Zurich in Finnegans Wake (he had already listed a few echoes of our ‘Sechseläuten’, the Zurich spring festival). This pushed me over the edge; maybe the edge had been waiting for me anyway. I took the hint, set to work and laboriously went through the Wake to cull references to my city and country. Like any fervent novice, I was grabbing at everything in sight. My juvenile enthusiasm has its current equivalent in the email exchanges concerning the Wake in recent years. It is one of the delights that we do get carried away. I sent drafts to Atherton and Adaline Glasheen, who both diplomatically curbed my zeal, weeded out a lot of tenuous chaff and stressed compositional stringency and reticence. The result was submitted to The Analyst, a mimeographed publication from Northwestern devoted to Pound and Joyce, and became ‘Swiss German Allusions in Finnegans Wake’. I now disown this piece of hit-or-miss exuberance, a species still going strong and probably rampant in reading groups anywhere, manifestly including those on the Internet.

When in London in 1958 I took the train to Wigan to meet Jim Atherton in person, and was welcomed into his family. He advised me to look up words first in Skeat’s Etymological Dictionary, and he strongly recommended Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, advice I have always passed on. Atherton was one of those who probably needed Brewer least, for he still commanded that knowledge that had once been common but was already rapidly dying out. It is amazing how, without a concordance, he managed to excavate all those references that he collected in his Books at the Wake, to me still one of the most informative studies around. Atherton later took part in the first Dublin symposium of 1967 and participated again in the Paris one of 1975. There Jacques Lacan, who had heavily relied on Books at the Wake for his famous opening lecture, whisked him away to a party and introduced him to Roland Barthes. Atherton, feeling out of place among top French intellectuals, was asked for a brief thumbnail sketch of Finnegans Wake. As he related, he uttered something like, ‘C’est une espèce de dédale.’ It must have been an odd constellation of experts.

In later years the Athertons (Jim’s wife was called Nora) liked to spend their holidays near the Alps and often stayed with us in Unterengstringen, near Zurich. The last time was in the summer of 1975 when the Suhrkamp edition of Joyce was in its last stages and Hans Wollschläger, its translator, and Klaus Reichert, the co-editor, met for final revisions. We shamelessly picked Atherton’s brain for the coda of ‘Oxen of the Sun’, that baffling medley of voices. As it happened, we had the expert at hand who could give us insights that non-native speakers could never have had, a unique piece of luck. I am sorry to note that his crucial help was never acknowledged.

Atherton, who had a Catholic background and was widely read, taught in a mining college, not a university, and so was never recognized academically as a Joycean. The one academic Joyce scholar at the time in Great Britain was Matthew Hodgart at Cambridge; he had published pertinent articles and later collaborated with Mabel Worthington on the songs. We did meet a few times, especially with the Finnegans Wake reading group in Brighton and Amsterdam, and I only wish I had come to know him better.

You mentioned that it was Atherton who put you in touch with Adaline Glasheen and Thornton Wilder.

Adaline Glasheen was one of my earliest correspondents and very encouraging in my formative stages. She was one of those enthusiastic amateurs, motivated by her enjoyment of the Wake mainly, though not exclusively. Her particular hobby was to identify characters, and in this she reached out very far and tended to overread, as we all did. I think we owe more to her impetus than her actual findings, collected in three versions of her Census ofFinnegans Wake. Its first supplement she called ‘Out of my Census’. Inevitably, she became one of the foremost contributors to our Wake Newslitter. Her extended correspondence with Thornton Wilder has become available in a book, supremely edited by Edward M. Burns, A Tour of the Darkling Plain (2001). Its value is not so much in particular glosses as in the atmosphere of the pioneering exploration of the Wake. I now realize that when one becomes a tiny part of such a book, which I did, since they reported on the letters Wilder and Glasheen had received from others, some details may become uncomfortably public. We can now read (correctly) that I did in fact do a great deal of whining, and my unspecified hints at depression may well have irritated my correspondents. Incidentally, it is ironic that we should have a meticulous edition of a marginal correspondence of two Wake pioneers, but not yet anything remotely like a reasonably complete collection of Joyce’s own letters.

Adaline Glasheen was most encouraging to a timid newcomer at a difficult stage; I had only a few tiny Wake comments to my credit. She was entertaining and witty, one of the best letter-writers ever, brilliant, volatile, erratic, always playing her own game. To me she was the modern equivalent of those women who in previous centuries would have run a literary salon in Paris, London or Weimar.

The weekend I came to Buffalo in 1968, after years of corresponding, she was already on campus engaged in some research of her own, and we met in person. She struck me as wispy and witch-like — and this is entirely complimentary. There was something unpredictable about her. She would never do what was expected of her; on panels she was prone to change the topic and stray far afield, which went against my own centripetal bias. I remember that Hugh Kenner, who also admired her inspired volatility, once characterized her as Dionysian. In her home, oddly enough, she appeared rather shy and subdued. It was in Buffalo, incidentally, that I also encountered Jack Dalton, and we had our memorable excursion to Niagara Falls.

In later years she also attended conferences and symposia. She struck up a friendship with Claude Jacquet, and this often brought her to Paris. I heard that she and Claude attended a Vico conference in Venice in 1988, but afterwards I lost touch. Her later years were overshadowed by a lingering disease, and I am sorry to say that I lost contact, due to a sort of negligence which I now find very hard to excuse.

And Thornton Wilder?

James Atherton and Adaline Glasheen had been exchanging letters for years, and she in turn had been conducting a lively correspondence with Thornton Wilder, mainly about Finnegans Wake and, with less intensity, the rest of the world. So Wilder and I corresponded a bit. One Sunday morning in 1959 the phone rang, and at the other end was Thornton Wilder, calling from his Zurich hotel and asking me to join him there. We spent the whole day together. He carried his heavily annotated copy of Finnegans Wake with him, in which I could not even make out the page numbers amidst the minute pencil scribblings. In the evening he took me to the theatre: it so happened that Nestroy’s Einen Jux will er sich machen was showing, the play on which he had based his own The Matchmaker and which then was successfully turned into the musical Hello Dolly. Analogously, Finnegans Wake had served him as a stimulus. When he was attacked for the adaptation, or even plagiarism, he countered that he had always seen literature as passing on the torch, as Joyce himself had done. We remained in contact afterwards since he and his sister Isabel generally spent a few days in Zurich each year. He even became a sort of unofficial godfather of my younger son Beda.

After the war, Thornton Wilder was among the most popular American writers in Germany when English or American contemporary literature became accessible to readers. During the war, his The Skin of Our Teeth had been performed in the Zurich Schauspielhaus, which was then the best theatre in the German-speaking area, as it employed refugee actors and ran plays that were forbidden in Germany, such as some by Berthold Brecht. I was told that those translating the play did not know what to do with its title — even a dentist was consulted — until Professor Straumann discovered that the phrase was a quotation from the Bible. It was aptly called Wir sind noch einmal davongekommen — we scraped through one more time.

Bernard Benstock crops up many times in your reminiscences. He must have been one of your earliest contacts.

For me he surfaced as a name in PMLA, where a thesis on Finnegans Wake was listed in a small note. I wrote to him, c/o the university at Baton Rouge, LA, and the letter reached him. I suppose he must have been flattered, an unknown emerging scholar being approached by someone equally unknown across the Atlantic. He soon got one of those Fulbright scholarships to Iran, or was it Iraq (in those days they sounded almost the same), and on the way back he and Eve, with their daughter Kevin (I think they expected a boy but stuck to the name anyway) came to Switzerland and stayed with us in Unterengstringen, the first of a long series of visits. For me this was a rare opportunity to talk about Finnegans Wake. And talk we did, intensely. And we often went for walks either along the river Limmat or on the nearby hills.

On one such walk his daughter put her hand on a nettle, and we admired her linguistic inventiveness when she cried out: ‘I bit myself!’, most likely analogous to ‘I hurt myself.’ Berni also told me of his experience in Iran, and I think it was Iran, teaching American literature. The difficulty was the concept of irony which, he said, his students did not grasp.

In 1966 we met again in Dublin, and we, both professional pedestrians who did not even drive, spent most of the time walking its streets à la recherche of Joycean connotations. On Bloomsday we had dinner in the (entirely renovated) Ormond Hotel and coming out, we saw a rainbow spanning the Liffey. I thought the Joycean touch had been overdone, but we proceeded to The Bailey in Duke Street, since Niall Montgomery had given me John Ryan’s address. We found John Ryan and introduced ourselves and were soon introduced to Anthony Cronin, whose book, A Question of Modernity, I knew, and he regaled us with anecdotes concerning his friend Paddy Kavanagh in London. When once they came to the building that replaced the one that the poet Thomas Hood had lived in, Kavanagh lay on his back in front of it and began to recite: ‘I remember, I remember, the house where I was born’. Strange that I should remember just that.

Of course, coming into The Bailey, Berni and I had both ordered a pint. John Ryan immediately offered another, ‘on the house’, and since it was close to chucking-out time, yet another round was offered. I was facing three pints and did not quite know how to cope. I must be one of those mixed middlings, with no capacity for accumulated stout, and would make a poor Irishman. The evening was entertaining, and John Ryan helped us a great deal a year later when the symposium was brought to Dublin.

I must have mentioned Berni in connection with the symposium of 1967 as he became its American co-ordinator (since Tom Staley spent the preceding winter in Trieste). Our triad, almost overnight, became the organizing committee and thereby achieved status. Berni’s first job was at Kent State, and he revelled in stories about Father Bob Boyle’s exploits as a visiting professor. He later moved to Champagne, Illinois, before he and Shari, his second wife, went on to Tulsa and from there to Coral Gables, Miami, where those memorable Miami J’yce birthday conferences were soon initiated. Berni, along with Zack Bowen, also started the James Joyce Literary Supplement.

Berni Benstock was prolific and wrote many books and articles on Joyce and various other subjects; detective fiction was one of his sidelines. Once, on his way to a few weeks of teaching in Buffalo, he said that he would have to write three articles within days. And he could do it. He had a facile, perhaps at times a trifle too facile, way of gathering and presenting his material, and he always added a new twist. He is easy to read.

Berni always had good, practical ideas. It was he who suggested (though the idea may not have originated with him) that the chair of any panel should speak last so that he or she would ensure that the others would not go much overtime. I believe that he, or we together, once decreed that every panel should have international representation, not just consist of a parochial group or a few buddies. And for a while it was enforced. He also instituted the Living Book Reviews, that is, live reviews of a Joyce book with the author ready to respond. It sometimes worked well, but not always, for the presence of a live author tends to favour backslapping or courteous praise and only muted disapproval. Absent authors are more prone to be in the wrong.