Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Pakistan's finest women writers – Jamila Hasmi, Mumtaz Shirin and Fahmida Riaz among others – introduce us to the compelling cadences of rich literary culture. A naive peasant is left with a white man's baby; a frustrated housewife slashes her husband's silk pyjamas; a middle-class housewife sees visions of salvation in the tricks of circus animals… Equally at ease with polemic and lyricism, these writers mirror the events of their convoluted history – nationalism and independence, wars with India, the creation of Bangladesh, the ethnic conflicts in Karachi – in innovative and courageous forms. Influenced both by the Indian and Islamic traditions of their milieu and by the shocking impact of modernity, they are distinguished above all by their artistic integrity and intellectual honesty.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

KAHANI

SHORT STORIES BY PAKISTANI WOMEN

Edited by

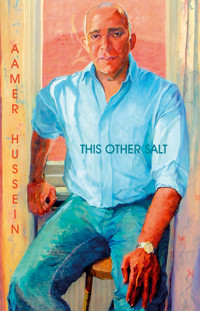

Aamer Hussein

SAQI

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Azra Abbas, Voyages of Sleep

Altaf Fatima, When the Walls Weep

Khadija Mastoor, Godfather

Hijab Imtiaz Ali, Tempest in Autumn

Hijab Imtiaz Ali, Two Stories

Mumtaz Shirin, The Awakening

Mumtaz Shirin, Descent

Amtul Rahman Khatun, Grandma’s Tale

Fahmida Riaz, Some Misaddressed Letters

Jamila Hashmi, Exile

Farkhanda Lodhi, Parbati

Umme Umara, The Sin of Innocence

Khalida Husain, Hoops of Fire

Glossary

Biographical Notes

Foreword

Two events before the March 1999 publication of the first edition of this anthology made me wish I’d had time to add at least two more stories.

To begin with, just before the start of the year, I’d finally come across, in my local library, a collection of all the short fiction A.R. Khatun had written. It was a book mostly of wonder tales, aimed at children, but of great interest to readers of any age, as the author herself remarks. I’d always wanted to include Khatun, whose work I hugely enjoy, in my book – not least because her very name makes some Urdu litterateurs go up in righteous smoke – but her novels were nearly impossible to extract and the one story I’d come across was unrepresentative. Among the fairy tales in the collection I now had were three moral tales set in modern times. Two of those chronicled partition; both were perfect for inclusion. I was also aware that the book would be appearing on the eve of the centenary of Khatun’s birth.

Then, on that day in March ’99 when the first copies of the anthology were made available to the public, a Pakistani critic told me: another Pakistani writer I hugely enjoyed reading, Hijab Imtiaz Ali, had died in her 91st (some said 96th) year. I did have a story by her in the book, but wasn’t satisfied with it; I’d rather have translated one myself.

Now, nearly eight years after that first collection, comes this revised edition with fresh translations of stories by these two writers whose work deserves to be known by an audience unfamiliar with Urdu. These were done by Sabeeha Ahmed Husain, who read both writers as a young girl and whose effortless bilingualism makes her an able interpreter of their (at times) difficult idiom.

Both writers – Khatun in particular – raise questions about inclusion in canons. Khatun has been seen as a writer of escapist romances and a purveyor of conventional morality. However, her fairy tales and children’s fiction gained her great praise in her lifetime, and it is from these that I’ve chosen one example.

Of her modern novels, one younger contemporary, Altaf Fatima, remarked that they were a reworking of older, lusher styles – the dastaan or traditional romance, yes, but also the reformist qissas of the redoubtable Maulvi Nazir Ahmad, who set out to educate his daughters with edifying stories in the 1860s (which Khatun would have read as a child); he was the first popular Urdu novelist in colonial times. Another younger contemporary, Farkhanda Lodhi, after damning her senior with very faint praise, proceeded to point out that not only was Khatum mining the same terrain – i.e home and hearth, partition – as the hugely acclaimed Khadija Mastur in her novel Aangan (translated as The Inner Courtyard by Neelam Husain in 2000); she was moving ahead of her more radical colleagues who had portrayed partition’s devastations by showing us the refugee incomers settling among the natives and interacting with them while making new lives for themselves. To all this I’d add that Khatun’s best novels engage quite fearlessly with the histories of her time, from WWI and the freedom movement through to decolonisation and life in post-independence, post-national Pakistan. And all this with a light touch, in crisp, spare prose, and with a dash of social satire. The story I’ve chosen here, stylistically poised between her adult mode of telling and the achieved simplicity of her fairytales, illustrates many of her characteristic themes while doing a number of interesting things. Firstly, it employs a tripartite narrative structure – one first-person narration encloses another within an omniscient narration. Secondly, it revels in its own fictionality – the narrator of the enclosed tale remarks upon her use of symbolic names (including the name of the heroine, who recounts the tale, or oral history, within the tale); she spins homilies as she goes along. On one level, then, it is a fable of strife, struggle and upward mobility, a modern fairytale of a brave, exceptional but absolutely common and ordinary woman’s economic self-actualisation. On the other, it seems to indicate its status as lightly fictionalised essay: it begins with a history lesson, and the events narrated are staged in the blinding glare of historical awareness (ethnic and religious warfare, migration, resettlement) and social realism.

‘Grandma’s Tale’ works, on a first reading, as a story in praise of free trade and entrepreneurship in which we observe a migrant making good by acquiescence to nationalist/capitalist norms and conventional morality. It ends with the heroine’s chilling admonition, of which Ayn Rand would approve: if you want respect, you’d better be as rich as me. However, the story’s dialogic structure allows the two narrators to debate the moral purport of new riches, corrupt migrants, and a social climate which encourages mendacity, moral ambivalence and shady dealings. And all this a mere fifteen years after the founder of the country’s death. Hard work is praised, but within the rigid boundaries of a liberal Muslim work ethic of honesty, charity and fair trade. No Ayn Rand in spite of the shared initials, Khatun, in her valedictory conclusion, far from endorsing its heroine’s economic policies, deconstructs the story’s ending with these comments on the brash, opportunistic new world of mid-century, post-colonial Pakistan.

Finally, Khatun gives us a heroine who falls from from the shabby-genteel lower middle class to the lumpen world of domestic service and street trading, She leads her around the dark satanic mills with the gusto of those social realist women writers who dismissed her work as trivia. But unlike Mastur or Lodhi or Hashmi’s heroines, she makes her way out of the maze. Significantly, her heroine is destined to a nouveau riche paradise without any accompanying ironies: entirely self-made in a patriarchal world. Khatun, the heroines of whose most famous novels are not particularly concerned with educational or professional qualifications except as a prelude to married life, gives us here a widowed protagonist who, like the heroines of her fairytales, sets off to tackle adversity with only faith in God and raw courage as her weapons. Her position as a woman in a patriarchal society is never discussed; it’s the effect of the economic machinery of the world on women, not femininity per se, that interests Khatun. A quiet resurgence of interest in her work is growing among a group of contemporary feminists; many readers see her as a great storyteller who, by expressing the nascent concern with women’s rights within the religious-nationalist framework, pours new wine – or sherbet, rather – into the old bottle of the traditional or reformist Urdu romance. A translation of her novel Afshan is said to be underway.

Hijab Imtiaz Ali, on the other hand, is primarily interested in gender, particularly in the period (the sixties) in which the story Sabeeha Husain has selected was published. It is an example, like Khatun’s, of the author’s late style. Always unconcerned with historical events in her work, Hijab, also dismissed by many as a haute bourgeouise fabulist with little interest in mundane matters, set her early work in a land out of time and only elliptically recognisable as a dark mirror image of her own ambience and period (the aristocratic milieux of the Hyderabad nobility, and later the slightly less opulent, but no less snobbish, Lahore avant garde). She is, in fact, a highly self-conscious novelist, a postmodernist avant la lettre, concerned with the self-reflexive narration of memory and desire and the slippages of language which involuntarily reveal repressions, evasions and lack. And all this in an exquisitely stylised, imagistic language which is, at times, as fanciful as the pineapple sandwiches her hedonistic protagonists eat between their games of tennis and their boating trips.

Largely unconcerned with the world of the poor, Hijab, in her very first novella – the famous ‘My Unfinished Love’ (1932), in which the love between the teenaged narrator and her father’s much older secretary lends in the latter’s suicide – went for the jugular as she dissected the minute differences of class within the social structures of the aristocracy and the elite, showing the relative powerlessness of educated men without privilege or ancestral wealth forced to make their own way in the world. More particularly, Hijab is interested in passion, the great disruptor, which comes along to erase differences and fails, leading to madness, drunkenness and even suicide. For the men. The women survive, sadder but rarely wiser, to write (or relate) their stories.

Fluent in several languages, like the English-educated author, her frequent alter-ego, the ubiquitous Roohi, flies her own plane (also like Hijab, who took her licence in Lahore in the mid-thirties); she travels all over, often in the company of male friends, writes stories and seems free to follow her desires – except when it comes to marriage. Her friends, precursors of the women of the fifties and sixties, are almost anachronistically ‘liberated’ when she first calls them into being. In their turn, they mirror her emotional crises. She tells their stories. In the ’40s novel, Cruel Love, Jaswati falls for her cousin and fiance’s foster brother; knowing their relationship is impossible because of family loyalty (a euphemism for paternalistic feudalism), her beloved succumbs to illness (a frequent metaphor in Hijab’s world). In the ’50s, in the psychoanalysis-inspired Dark Dreaming, Sophie, obsessed with her drunk father’s memory, virtually sabotages the approved match she’s expected to make by falling in love with another drunk.

‘Tempest in Autumn’ reworks elements – alcohol, women’s masochistic obsession, art and life – of that earlier novel, replacing the lush, cinematic exteriors of her youthful fictions with one sparely-evoked interior and the offstage sounds of sea, wind, birds and falling leaves, either because Hijab expects us, in the fourth decade of her career, to be utterly familiar with Roohi and her ways (i.e, that she’s in search of material and will be writing up her findings), or because by now she’s so much in command of her material that she expects the minimalist trappings to suffice. Poet and critic Alev Adil sees the setting as cinematic in the mode of Douglas Sirk’s melodramas; I am reminded more of radio, since the story is a two-hander played out almost entirely in dialogue and, consequently, its effects are largely aural.

In her psychonalytic probings, Hijab dismantles one pre-conception about Eastern women – she sees them as dominated by reason, not emotion. She challenges another, seeing the much-vaunted Muslim woman’s virtue of patience as a handicap and advocating swift action instead. Alev Adil, in fact, interprets ‘Tempest in Autumn’ as a fantasy directed by Roohi, who is both auteur and voyeur, with Zulfie now passively, now obediently feeding the older woman’s fantasy. In this film of recovered memory she projects, Roohi as writer-director, while she watches the hysterical performance that she herself instigates, also takes a sort of revenge on Zulfie for daring to love, as she has herself often done in her youth..

The ambivalent conclusion (is it in Roohi’s imagination?) bears out this reading. Is Zulfie really hiding her innermost feelings, or is she merely the innocent dupe of an amoral drunk? Hijab’s open ending leaves room for more than one interpretation.

Hijab carefully constructed her own persona as the romantic artist who spent hours flying her plane, playing her organ, tending her many cats, writing her diary in candlelight while bombs fell on Lahore. It was a performance to which many visiting writers were treated, and, by the end, the persona that was, in fact, designed to erase differences between author and narrator was to overshadow her literary reputation. Hijab became a legend in her lifetime; at least one contemporary critic, Samina Choonara, called her Pakistan’s Barbara Cartland. Adil, as a non-Pakistani, is incensed by this comparison, placing her dream-narratives as precursors of the nouveau roman and her surrealistic style as similar to the enigmatic English modernist Anna Kavan, described as ‘Kafka’s Sister’ by Brian Aldiss. Hijab’s was indeed a hybrid art: among early influences were the Arabian Nights, translations from Turkish and the Orientalist writings of French decadents Pierre Loti and Pierre Louys, but her first fictions were equally entrenched in – feminised rewritings of, one might say – the Urdu and Persian tradition of verse romances to which she frequently refers. Her late style, however, appears to dispense with all influences except that of Freud. The setting, too, has changed: the seaside city may or may not be Karachi, but the milieu can be recognised as mid-century Pakistan, with its alcohol-fuelled soirees, the appropriation by wealthy dilettantes of traditional music and art, and its avant garde poised uneasily between social acceptance and opprobrium.

Hijab’s and Khatun’s are two very different examples of mid-twentieth century fictional practice: one reluctantly endorses sanity while exalting the ecstasy and madness of love and art in a prose that borrows from dream and the discourse of the unconscious; the other casts her stories in the clear light of reason and pragmatism. On the margins of the mainstream of contemporary Pakistani women’s literary preoccupations, they are nevertheless similar in their concerns to other writers in this anthology: compare Hijab’s dreamworld, for example, with Azra Abbas’ reverie or Khalida Husain’s fable, or read Khatun in tandem with Hashmi and Fatima. The results will be, at the very least, interesting.

Aamer HusseinLondon, March 2005

Preface

In the period following the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, Urdu literature in Pakistan has developed a dynamic identity of its own. It retains, on the one hand, sociolinguistic links with Urdu literature in India, and reflects, on the other, the demands and vagaries of a new chapter of history that is in the process of being transcribed. It raises interesting questions of autonomous cultural identity and the ever-evolving relationship of art with politics. Contemporary Pakistani literature also reveals fascinating parallels with the literature of other nascent post-colonial societies and engages fearlessly with the genres and modes produced in the ‘developed’ countries of the West, redefining and reconstructing them to its own purposes.

Urdu literature has yet, however, to be accorded its rightful place in the annals of world literature. The South Asian writers who have recently gained renown in the West are all Anglophone and are usually subsumed under the Indo-Anglian label. With a handful of honourable exceptions, those writers who have been translated from national/regional languages have been relegated to the confined space of academic journals. For all the lip-service paid to their achievements, the space given to women writers is negligible, particularly when one considers the major contribution they have made to experiments in form and subject over the last half-century, equalling and often surpassing their male contemporaries.

It was not my original intention to produce an anthology devoted exclusively to women, but my publishers rightly pointed out the gap and my own readings in Urdu fiction served to confirm the decision: too much writing by women has suffered neglect over the past half-century. We Sinful Women, Rukhsana Ahmad’s pioneering anthology of contemporary feminist poets in translation, introduced Pakistan’s women poets to an Anglophone audience; in the present book, an anthology of short fiction translated from the Urdu, I make an attempt to redress the balance by presenting a number of prominent and lesser-known women writers of short fiction. Their stories are accessible and yet often challenging in form; in content, they are at once universal and deeply rooted in the particular experience of a nation and its psyche.

A theme emerges, perhaps: that of the effect of the first forty years of the country’s history-from partition until and after the death of Bhutto-on the imagination of its women. Though purely subjective experience is also in evidence here, those writers who traffic less in political and more in personal experience have nevertheless been liberated into writing by the politically conscious writings of the first wave of literary women. Their dream worlds are illuminated and darkened by the vagaries and vicissitudes of the society that shapes them. Fahmida Riaz’s Amina, exiled in India, sees her alienation in sociohistorical terms: she writes ‘a number of passionate poems, exposing the gaping flaws in a democratic system that still allowed for horrifying poverty’. Khalida Husain’s nameless narrator in the title story moves in a metaphysical darkness: ‘And am I not answerable to that world, beyond the Third World, that lives within me?’ Yet their wistful loneliness is identical.

Several stories, translated especially for this selection, appear here for the first time in English; others have previously been available only in Pakistan. I hope they serve to urge other editors and translators to make their much-needed contribution to the field of translating contemporary Pakistani fiction. This is particularly relevant, as Pakistan is now nearly three decades old. Its fictions are the literary mirror of a turbulent history and the partition of a language; its women writers, always an equal force in this culture, have not only been vital contributors to the art of fiction, but have often renovated and even subverted its prevalent discourses.

The major Urdu writers, and indeed its emerging young writers who have as yet to secure their reputation, contribute much to an international debate that seeks to decentralize Eurocentric aesthetic theories and notions. Several of the authors included in the anthology are also novelists, but the short story has a place in South Asian literature second only to poetry, and Urdu writers have almost without exception showed great mastery of the shorter forms: the story, the tale and the novella. Handling with equal ease the romantic and unrealistic modes inherited from past tradition, European realism, Marxist-inspired protest writing and the postmodernist strategies characteristic of our century, they have demonstrated that the development of fictional techniques is, in spite of ongoing ideological debate, not so much a question of conflict or opposition between realism and fantasy, tradition and modernity or art and politics, but an often contradictory juxtaposition of opposites in an imaginative and linguistic crucible. Modern Urdu literature, widely held to be descended from the edicts of the socially orientated Progressive Writers Movement, has nevertheless retained its links with indigenous pre-novelistic modes, and it is this coexistence of apparently irreconcilable elements that modern writers have creatively exploited.

Although the anthology focuses largely on writings from the 1960s to the 1980s, the pieces by the two writers here who rose to prominence earlier – Mumtaz Shirin and Khadija Mastoor – effectively illustrate the two dominant tendencies, respectively the aesthetic-fabulist and the social realist, yet each displays traces of the antithetical tendency in her work. Mumtaz Shirin’s piece is an early monologue, written while she was still in her teens, which shows at once her modernist aesthetic and her understanding of women’s need for self-expression. Khadija Mastoor, as a feminist, focused with brilliance on the lives of dispossessed women, and her story here, Godfather, mirrors her preoccupations. Women of the underclasses are often her central characters and though her stories are in method ostensibly realistic, poetic diction and picaresque situations link her work to older narrative modes. This section also includes stories by the doyenne of Pakistani fiction, Hijab Imtiaz Ali.

Mastoor and Shirin belonged to the generation of Ismat Chughtai, who chose to remain in India at partition, and Qurratulain Hyder, who migrated to Pakistan at partition but later returned to India. Hyder left an enormous gap in the world of Pakistani literature, but her influence is everywhere. Also from this generation of trail-blazing women writers are Jamila Hashmi and Altaf Fatima, who can be called the inheritors of Hyder’s mantle. Hashmi was in the forefront of women’s writing in the 1960s and insisted on giving equal space in her fiction to Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, stressing a common cultural experience. Her radical feminism is often refracted through the perspectives of male narrators, through whom she incorporates in her stories a critique of patriarchal norms, thus raising burning questions about class and gender. Arguably – and perhaps, in the Pakistani context, unusually – a better novelist than she is a short-story writer, Hashmi is represented here by her famous story of rape and exile in the wake of partition, Exile. This is one of my favourite stories in any language and combines, in my opinion, the sociohistorical canvas and the sweep of her novels with the subjectivity of modernist short fiction and the lyrical intensity of a traditional ballad.

Altaf Fatima, who belongs to the generation of Hashmi and Mastoor and is also a fine novelist, has in the last decade displayed an excellence in the short-story form that places her in the first rank of Pakistan’s writers. Her story here combines traditional narrative and postmodern polyphony with an overlay of political protest to tell the tale of a peasant woman’s seduction and betrayal by a Western anthropologist.

The next generation of writers, who were born around the 1930s and 1940s, often disclaim ‘national’ or local influence and identify with Camus, Kafka, Marquez and Kundera. However, they have all inherited a passion for indigenous myth and parable and tend to present even their most political statements in a framework of fable and poetry. Since several of these writers are from the Punjab, they have introduced a strong local and rural flavour to the Urdu language, using it to depict a recognizably Pakistani landscape rather than the elegant, urbanized northern India so often evoked by the earlier generation. Partition also figures far less in their work; their metaphors and tropes usually represent current concerns such as military oppression, patriarchal and feudal norms, sexuality and gender discrimination.

Included here are Farkhanda Lodhi, Umme Amara and Khalida Husain. The latter is often considered to be this generation’s finest exponent of the short story; she locates the perspective of urban women in a semi-fantastic but recognizably Pakistani landscape, and creates new legends that articulate the social and political preoccupations of a new age in a tone that simultaneously evokes ancient bards, epic poets, Kafka, Camus and Woolf. The title story has been chosen from her work. Lodhi can be seen as the natural successor to Mastoor; her fiction, however, reflects her Punjabi roots in its robust diction and folksy settings. Umme Amara’s study of the 1971 war for Bangladesh completes this section.

In the range of their preoccupations and experimentation, writers born around partition and after equal much Anglophone writing from any continent, and are possibly closer in spirit to the writings of Assia Djebar or Hoda Barakat. To complete the collection we have two of these: the trail-blazing poet Fahmida Riaz, who has recently turned to writing fiction and is one of the country’s finest writers in any genre – her bold, highly political stories defy generic classifications; and Azra Abbas, who writes both poetry and prose. These writers effectively display the influence of their predecessors, both Eastern and Western; they maintain a careful balance between the continuation of a thriving literary tradition and the changes of strategy demanded by the state of continuous flux in which they live.

Aamer HusseinLondon, November 1997

AZRA ABBAS

Voyages of Sleep

1

The feet walking on water were ours indeed.

And you desired to touch the rustling clothes –

Are your fingertips stained with our rosy colours?

Do you know that butterflies are looking for the very same colours? But you mustn’t touch them – they will fly off with those colours and our feet, walking on water, will see them fly but won’t be able to stop.

But will those feet be ours?

Because then, sitting by our mothers’ sides, we would be stitching clothes and a spicy, dust-coloured odour would be emanating from kitchens.

Is it true that in days to come, scorching on the other side of the sun, our bodies will account for their sins and birds will fly off with our eyes hidden in their feathers?

Is this true?

But now our hands are fragrant with words more powerful than love and we get up from our beds at night, for our bangles start jingling by themselves and the soft light from our arms flows afar as fragrance.

So where do we wander to?

O lights, following us in the dark!

Why, in the desire to walk on open waters, are we always given to the immobility of our abodes? Where, far away from us, are our dreams rejoicing? Why has the bright evening form estranged us?

2

Pillows lie on empty beds like forlorn girls. Music, bustling with the wind, sinking into the flesh, the sky looking for water, people returning home – far, faraway heads droop with heavy dreams – a cold water stream runs through our bosoms and white birds fly about with water in their beaks, pairs of pigeons chase each other, ships anchor on shores and someone lightly touches the shoulder.

Virgin blood! You’ll return from those shores as sunshine has spread over half the oceans and flowing footsteps have taken up cramped journeys – give away the eyes panting around loneliness and the miseries of the journey to the senseless path.

Far away, among dense, white-flowered trees, sounds of footsteps do not look back for opulent oceans – here, journeys are soundless and dream-forms, like pounded cotton, pass away unendowed.

Sufferings of the night increase in diminishing light and desires can be heard like the hooves of horses on flat, even roads – we have no clue of days to come – countless staring eyes, like black rocks climbing down dark trees, move toward the oceans and bodies are half-burnt in the half-spread light of the sun – outside the whirl of trees, shadows of winds, sounds and moments go on extending, and skies, unable to bear this are closing in.

Prayers, escaping from the palms, are now part of the imperceptible air.

3

Picking shells from raw earthen walls, staying awake with the night, inscribing their impressions upon dark, stormy, fate-chasing winds, lips loaded with prayers – and in the quietness of burning afternoons, like the sweetness of a love-laden name, our maidenhood.

And O God!

This forest, accompanying us like an invisible shadow, leaves its naked songs in our bodies and resembles people who quench their thirst from snake-filled ponds.

Eyes of a frightened sparrow, broken wings, with innumerable flightless fears and the first utterance of a homeless, newborn babe, like heavenly rains, create words that permeate the lips with the fragrance of chaste prayers.

Before dusk, the desire for a journey that impairs the joints, heels submitting to travel and weightless moments burdening the body persist within us, but night demands accountability for its loneliness and breaking away from the unseen sky, to endure the suffering of hapless days, we free ourselves.

Where is the wakeful eye grieving the half-moon and where is the vision not bound by dreams?

Where is it all that’s in the darkness?

O light of time – sifting through songs of moments, just a sip’s thirst!

Where is it all?

That’s in the darkness?

Translated by Yasmin Hameed

ALTAF FATIMA

When the Walls Weep

Horse-drawn carriages are gradually being eased off the streets of Lahore (newspaper headline).

Wild animals are a national resource: it is our duty to protect them (poster on a wall).

And the wall says: I am not that wall the builder made with the help of a mixture of mud, cement and concrete. I am that wall made by the sun and the moon which human beings call the beautiful hills of Margalla. And I wish I could show the poster to the owner of the black Mercedes that knocked down a child sitting behind his brother on a scooter very near a school, crushed him and drove away.

And what of that other child, the one I must travel so far to find? Perhaps he is waiting for me.

But he doesn’t even know that we’re going to get him. It doesn’t matter. His blue eyes, his jute-blonde hair … He must be very lonely there, and unhappy.

The story that Gul Bibi told the villagers is the one I watched, scene by scene, for six months. But I swear by the dark night that I have not heard a word of it until today, though I have it all on tape within me, from start to finish, and in her own words.

Who? What? When? Why?

She herself will answer all your questions.

You only have to bear in mind that she’s a woman – a woman of the valley, at that. And all valley women – never mind which valley, Kashmir, Kaghan or Kalash – remind one of ripe apples hanging from boughs on the trees of their gardens.

The characters of this story are all central: there are no extras. This is more or less the sequence in which they appear, according to the plot. A widow whose winsome daughter has just been wed. A blonde, blue-eyed foreign woman. And a blonde, blue-eyed tourist – or if you want to discard the cliché you could call him a research scholar, a student of anthropology – well, let’s continue, just listen to the tape.

— Someone in the bazaar had told me that a job was available in the Rest House. A foreign lady had just arrived. She needed a servant. I was starving. I lived near the mosque by the corner of the bazaar in my shack made of sticks and thatch. After marrying off my Mahgul I lay among my baskets like a rotten apple. When Mahgul left her, uncle stopped sending me money for my expenses, and I was starving. I went along as soon as I heard about the job and started work straight away. But the woman seemed a bit mad to me. Eccentric. She’d write all night with her light on, then fall asleep, wake up suddenly and stalk around her room. She’d be putting paper in her typewriter before the first call to prayer and I’d hear her tapping away. Then she’d wake me up, calling, Gul Bibi, get me some coffee. I couldn’t stand this habit of hers. During the day she’d go off into the woods to collect herbs, roots, leaves. Once she asks me, Gul Bibi, she says, does any one practise white magic in your village? I’d been wondering about her for a while, anyway. These are devilish practices, I tell her clearly, we Muslims don’t play around with magic. If our own herbs and poultices don’t work, we go down to some holy man for an amulet. And we don’t even have a holy man in our village. After that, I started to watch her. At night she’d take off all her clothes and stare at her naked body in the mirror. She’d go on staring and then begin to weep. But without a sound. Strange. Mahgul’s youth had taken mine away and the sight of this woman’s was bringing it back. I thought her spells must be working on me. But I had to feed myself somehow, after all. She was a good woman, though, just kept on writing, tapping away, then one day she’d go off to town with a stack of those papers of hers. She wouldn’t come back for days.

The tape breaks off at this point.

This is when he appears, in his blue jeans and checked shirt under his Peshawari fur jacket, his Swati hat and his backpack and his camera. And settles in the Rest House. (Wait … I’ve sorted out the sequence of the tapes again. Just let me adjust the sound a bit …)

— He settled in so comfortably that I just assumed he was her man. I hardly needed to ask her about that. She’d spend whole days in the woods, gathering her sticks. And he, perched for hours on the white rocks by the Naran, would bait the trout hiding in its waters. He’d trap about a seer of trout a day … (Stop. When my boys tried to catch some trout in the Naran they were stopped by a guard. Who created a great fuss. And we thought, well, if we can’t have trout, we’ll have some corn on the cob instead. It’s so sweet, so succulent here. Grains of corn, fields of maize … thoughts, like a top, spinning here and there, at the gates of schools, around hours of play, horses, silence, seed-pearls … And a child with eyes as light and clear as the waters of the Naran and hair as bright as sheaves of corn waiting, waiting … For whom? For me, perhaps …) Cut! The button of the tape recorder’s been switched on again. Automatically – or by demonic interference? The voice: a man in the bazaar.

— After the foreign lady left, the man that Gul Bibi had taken for her lover stayed on for another week. And then one day with his pack and his camera on his shoulder, he strolled up to the Rest House’s cook on his long legs and told him to give Gul Bibi her mistress’s keys when she got back.

— I saw him go off on the Kaghan bus. Gul Bibi was ill that day. She lay on her bed in her shack all day, with her scarf over her face. When I gave her the key the next day she couldn’t believe it. She went on repeating to the mullah, the gentleman shouldn’t have done that, he shouldn’t have left the lady’s keys with Gul Khan. Who knows what he’s walked off with …