Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The mass murder of 22,000 Poles by the Soviet NKVD at Katyn is one of the most shocking events of the Second World War and its political implications are still being felt today. Information surrounding Katyn came to light with Russian perestroika, which made it possible to disclose a key document indicating the circumstances of the massacre. The bitter dispute is ongoing between the Russian and Polish governments, to declassify the rest of the documents and concede to genocide perpetrated by the Soviets. British 'Most Secret' files reveal that Katyn was considered as a provocative incident, which might break political alliance with the Soviets. The 'suspension of judgement' policy of the British Government hid for more than half a century a deceitful diplomacy of Machiavellian proportions. Katyn 1940 draws on intelligence reports, previously unpublished documents, witness statements, memoranda and briefing papers of diplomats, MPs and civil servants of various echelons, who dealt with the Katyn massacre up to the present day to expose the true hypocrisy of the British and American attitude to the massacre. Many documents are unique to this book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 625

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

If it be the case that a monstrous crime has been committed by a foreign government – albeit a friendly one – and that we, for however valid reasons, have been obliged to behave as if the deed was not theirs, may it not be that we now stand in danger of bemusing not only others but ourselves? … We ought, maybe, to ask ourselves how, consistent with the necessities of our relations with the Soviet Government, the voice of our political conscience is to be kept up to concert pitch. It may be that the answer lies, for the moment, only in something to be done inside our own hearts and minds where we are masters. Here at any rate we can make a compensatory contribution – a reaffirmation of our allegiance to truth and justice and compassion.

Owen O’Malley

Dedication

To my life-long friend and mentor, prelate Lt Zdzisław Peszkowski, survivor of Kozielsk camp, who in 1944 became a Scout leader to thousands of Polish refugee children – myself included – and to Dr Zdzisław Jagodziński, historian, librarian and first editor of the Katyn bibliography, my courageous friend and colleague; both now departed, without ever seeing the fruits of their inspiration.

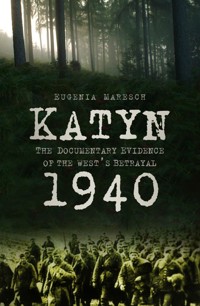

Front cover: Big Ben, Wartime London. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Library ARC 195565)

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Chapter One Drang nach Osten and Prisoners of War

Lieutenant General Mason MacFarlane’s Report • Lieutenant Bronisław Młynarski’s Report • Captain Józef Czapski’s Report • The Foreign Office Comments • Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Hulls’ Report • Professor Stanisław Swianiewicz’ Declaration

Chapter Two Katyn 1943

General Anders’ Speech • Ambassador O’Malley’s Involvement with Katyn • Second Secretary Denis Allen’s Opinion • Sir Alexander Cadogan’s Remarks • Diplomatic Dilemmas and Attitudes • German Secure Signals – Auswartiges Amt • SOE Interests in Katyn

Chapter Three Crime Scene Reports

Stanisław Wójcik’s MI 19 Interrogation • Ferdynand Goetel’s Recollections • Ivan Krivozertsev’s Deposition • Polish Red Cross PCK Involvement • Kazimierz Skarżyński’s Report • Dr Marian Wodziński’s Report • Captain Stanley Gilder’s Report • Wodziński’s Report Part Two • Skarżyński’s Report Part Two

Chapter Four The Foreign Office Attitude

German Reaction to the Soviet Report • Foreign Correspondents and J. Balfour’s Report • Interrogation of ‘Columbine’ • The Soviet Commission of Experts • Ambassador O’Malley on the Soviet Report • The Foreign Office Response • Sir Bernard Spilsbury’s Forensic Observations • Professor Orsós’ Confirmation of his Initial Report

Chapter Five FORD Analysis of the Burdenko Report

Professor Sumner’s Analysis • Sir William Malkin’s Judgement • Skarżyński’s Conclusions

Chapter Six Preparation for the Nuremberg Trials

Akcja Kostar • MP Guy Lloyd’s Involvement • Denis Allen’s Brief • Professor Savory’s Engagement • The Foreign Office Comments • Lord Shawcross’ Statement • Ambassador Bullard Remembers • Frank Roberts Comments from Moscow • Possible Charges against the AK

Chapter Seven BWCE and machinations at Nuremberg

The Germandt Affair • The Timing of Akcja Kostar • The Second Phase of AkcjaKostar • Polish Appeal for an International Tribunal • General Anders’ Plea • The Foreign Office Reply

Chapter Eight The American Committee

USA House of Representatives Select Committee • Convolutions of the Foreign Office • FORD’s Reaction to the Madden Report • Geoffrey Shaw’s Opinion • Ambassador Sir Oliver Franks’ Words of Wisdom • The British Government’s Last Stand

Chapter Nine Publications

Professor Hudson’s A Polish Challenge • Janusz Zawodny and Louis FitzGibbon • Miesięcznik Literacki • British Foreign Policy in the Second World War • The Daily Telegraph and The Sunday Times • The BBC Documentary

Chapter Ten Failure at the UN – Success with the Memorial

MP Airey Neave’s Involvement • Lord Barnby’s Brave Effort • Lord Hankey’s Brief • Parliamentary Debate on Katyn • Sir Alec Douglas Home and EE&SD’s Brief • The Katyn Memorial Fund

Chapter Eleven Gathering of Documents by the FCO

Rohan Burler’s Memorandum • Critical Appraisal of Butler’s Report

Chapter Twelve Actions and Reactions in Poland

Russia’s Response; The Polish–Russian Historical Committee • The 1940 Soviet Politburo Document • British Policy on Katyn in the 1990s • ‘The Unquiet Dead of Katyn Still Walk the Earth’

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grateful acknowledgements are made to various archives for permission to reprint previously published material as well as those documents recently declassified, upon which the bulk of this book is based. In particular the National Archives at Kew, the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, custodian of surviving records of the Polish government-in-exile based in London. Besides referring to the relevant official histories I have also drawn freely on recent publications by authors from Poland and these are acknowledged in the endnotes.

Debts of gratitude are owed to the personnel of the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, and the Polish Underground Movement Study Trust, the National Archives in Poland, the Central Military Archives and the Council for Defence of Memory, Strife and Martyrdom in Warsaw, for their support and encouragement.

Thanks are due to my family, friends and colleagues, amongst them Andrzej Suchcitz, whose counsel I have sought on many occasions, and to David List, especially for his meticulous eye for detail, whose critical reading of the typescript resulted in rational re-examination.

Appreciation is expressed to those who allowed me to use photographs from their family albums. All credits are noted in the captions to those libraries and institutions that provided images.

chapter one

DRANGNACHOSTEN AND PRISONERS OF WAR

Seventy years ago, Hitler’s quest for domination of Eastern Europe continued with a blistering attack on Poland on 1 September 1939. Seventeen days later, Stalin ‘plunged the knife in Poland’s back’, as agreed by both tyrants on 23 August 1939. The German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov signed the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, which contained a Secret Supplementary Protocol dealing with territorial allocations. Initially, boundaries had been along the rivers Narew, Wisła and San, but after the formal German-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Borders, signed in September, they settled on the Pisa, Narew, Bug and San. The new boundary stretched roughly east of Białystok, through Brześć Litewski (Brest Litovsk) to the west of Lwów (Lviv, Lvov), a south-eastern Polish fortress, which for centuries had withstood the invasion of Turkish and Tartar hordes. The Soviet strategy was to create two fronts: the Belorussian heading from Smolensk and the Ukrainian from Kiev, enabling a swift destruction of the Polish regular army divisions and some 24 Frontier Defence Corps (KOP, Korpus Obrony Pogranicza) stationed on the Polish borders. Under the guise of ‘rescuers’ of the Ukrainian and Belorussian minorities, the Red Army overran the eastern territories of Poland, always known as Kresy, inhabited by 12 million people – in just twelve days.

On 18 September 1939 the two aggressors met to discuss further political cooperation; a communiqué was signed, declaring that the sovereignty of Poland had been ‘disestablished’. The demarcation line was confirmed and the new territorial sphere of influence endorsed. As early as 19 September 1939, Lavrenty Beria,1 People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs, head of the Secret Police the NKVD (NarodnyKomissariatVnutrennikh Del) by order No.0308, had created a separate directorate of the UPV (Upravlenie po Delam Voennoplennykh) – an authority to administer wartime operations of the NKVD, primarily to deal with prisoners of war (PoW) headed by Major Pyotr Soprunenko.2

On 2 December 1939, Beria produced another official note for Stalin’s3 approval, which was endorsed by the Politburo of the Communist Central Committee on 4 December – to organize four mass deportations of Polish civilians to the wilderness of Siberia and other Soviet Republics. In 1940–1941, according to émigré sources, at least 980,000 were deported; incomplete statistics, gathered to date from GULag’sNKVD documents, show only 316,000. These were combatants of the 1920 war with their families, landowners, police and civil servants, ‘enemies of communism and counter-revolutionaries’, destined for hard labour and death.

December was also a month of intensive consultations between Germany and Russia on the subject of the massive prisoner problem. Three joint meetings of the security services the UPV and the Gestapo for RSHA, the Reich Central Security Office (Reichsicherheitshauptamt), were held to discuss the possibility of territorial exchange of the PoWs as well as relocation of forced labour to GULags in the USSR and concentration camps in Germany. It is possible that the fate of some 15,000 Poles detained in Soviet camps and over 7,000 kept in prisons was decided at one of these three meetings, Lwów in October 1939, Kraków in January 1940 and Zakopane in March 1940. It is as yet unknown, due to lack of documentation, if this treachery is analogous to, or part of, the German ‘pacification action’, the Aktion AB (Ausserordentliche Befriedungsaktion), designed not only to stop any resistance by the people but also to exterminate Polish leaders and the elite, which was planned by the Generalgouvernment in early 1940 and reached its height from May to July. AktionAB was sanctioned by Adolf Hitler and carried out by Generalgouverneur Hans Frank, Governor General of the occupied part of Poland, with its seat in Kraków and acting SS-Obergruppenfuhrer, head of the Nazi Security Service in Poland, ably assisted by Friedrich W. Kruger and others.

Soon after one of those secret meetings, the NKVD started to compile a list of their captives with full particulars as well as addresses of their families, including those under the German occupation. By February 1940, Soprunenko had sent to his superior Beria detailed proposals on the ‘clearing out’ (rozgruzky) of PoW camps at Kozelsk and Starobelsk. He categorised the prisoners as those too ill (about 300), and those who were residents of the western region of Poland whose guilt could not be proven (about 500); these were to be sent home.

‘Special procedures’ were to be applied to those who were ‘hardened, irremediable enemies of Soviet power’: officers, police, landowners, lawyers, doctors, clergy and political activists. They were to suffer the ‘supreme punishment’ by shooting, without prior call to face the charges in any court. Stalin and others of the Politburo duly signed the order presented to them by Beria on 5th March 1940. The executions were to start in early April and last till May 1940.4

‘Operation Barbarossa’, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, put an end to the volatile Nazi-Soviet Pact. For Poland it offered the opportunity to ally with the Soviets, albeit reluctantly and with British inducement. General Władysław Sikorski,5 Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, with the Soviet Ambassador Ivan Maisky, signed a Pact in London on 30 July 1941. It was an uneasy alliance, but had one important military outcome, as it allowed the raising of a Polish Army on USSR territory made up of deported prisoners. The agreement stated that all Polish citizens held in the USSR were to be released on ‘amnesty’ – an irrational term as no war had been declared between Poland and the Soviet Union. The Polish government-in-exile did not argue, perhaps they considered it as a ‘face saving’ gesture to the Soviets. The pre-war border issue was provisionally settled by an ambiguous statement: ‘The Government of the Union of Soviet Republics recognizes that the Soviet-German Treaties of 1939 relative to territorial changes in Poland, have lost their validity.’

The release of men from prisons, PoW camps and forced labour GULags started in September. By October 1941, it was clear that the majority of army officers were missing and there was no news of them. After repeated enquiries, which remained unanswered, Molotov and Stalin finally maintained that ‘all officers were released.’ The Poles had good reason to disbelieve them but were powerless to do anything about it.

A Top Secret report of those detained by the NKVD6 was prepared by Captain Pyotr Fedotov, head of 2ed Administration of the NKVD for his superior Soprunenko and handed to Stalin on the day he met with Sikorski and General Władysław Anders,7 Commander of the newly formed Polish Army in the USSR, on 3 December in Moscow. This most secret report indicated that the total number of prisoners of war captured by the Red Army was 130,242: some 42,400 were conscripted into the Red Army and a similar number, 42,492, were exchanged with Germany. Only 25,115 soldiers were released to join the Polish Army formation centres. 1,901 were rejected by the army or handed over to the German Embassy, some were invalided out, or counted as runaways, or were dead. Most importantly, Fedotov’s report included a reference to 15,131 men ‘disposed of in April-May 1940 by the 1st Special Department’, which surely indicates the officers of Kozelsk, Ostashkov and Starobelsk camps. Stalin avoided mentioning these during the Kremlin meeting. A much later document reveals that in March 1959, Aleksandr Shelepin, head of the KGB wrote a note for Nikita Khrushchev, 1st Secretary of the Communist Party and head of state, putting the figure at 14,552, which is generally accepted as a more probable number of those massacred from the three camps. Fedotov’s report brings the total – alive and dead – to 257,186. Again, by Western calculations, based on archival sources, about 250,000 is the more likely figure.

Absolute silence over the existence of these ‘missing’ prisoners baffled the British Military Mission in Moscow. Brigadier Colin McVean Gubbins, one-time member of the British Military Mission to Poland in 1939 and later head of the SOE (Special Operations Executive), was also concerned about the strength of the Polish forces, with the core of the military men missing or imprisoned. SOE’s aim was to foster resistance movements in Western Europe. Although the distance and geographical position of Poland made the task difficult, SOE did have a Polish Section, responsible for clandestine operations. They used the secure communication facilities of Oddział VI, the Special Operations Bureau of the Polish General Staff headed by Staff Lt Colonel Michał Protasewicz in London. It is through him that signals from the Home Army – AK (Armia Krajowa) were analysed, translated and distributed to various Departments, including the British.

Lieutenant General Mason MacFarlane’s Report

The British Cabinet Office already knew of the Polish plight through successive British Ambassadors, Sir Stafford Cripps (till December 1941) and later Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, as well as from No.30 Military Mission in Moscow, headed by Lieutenant General Noel Mason MacFarlane,8 who despatched his reports regularly to Major General Francis Davidson, Director of Military Intelligence (DMI) at the War Office. One ‘personal for DMI’ report, dated 7 August 1941, expressed his fears about the situation and unwittingly indicated a stance for the British Government to take. His words were prophetic:

I am frankly terribly worried about this Russo-Polish business. I see innumerable snags ahead. I won’t mention Polish BBC gaffs because they are too blatantly deplorable to merit further attention except that they MUST be stopped.

We are going to find ourselves being pulled in as mediators in a situation which holds promise of developing in the most awkward way. I only hope the business won’t sow a lot of discord.

What is going to happen when the Poles find out the number of Poles who have been ‘lost’ since 1939 is clearly an awkward one to answer. What will the British Press want to say when they find out? We’ve got to keep out of the affair asmuch as we can, and when we do intervene we must remember that Russia can help us tobeat Hitler, and not Poland.9 [Author’s italics]

Mason MacFarlane also advised the FO that Captain Józef Czapski,10 a plenipotentiary to General Anders, had raised the question of the missing officers during his first meeting with the NKVD. He was kept in the corridor for five hours and sent home with nothing. MacFarlane advised Czapski to deal directly with Vsevolod Merkulov,11 Deputy Commissar to Beria involved with PoWs, or alternatively, to go through General Georgy S. Zhukov, Chief of the NKVD, who was in charge of the affairs of the Polish Army in Russia and was on good terms with Anders. Mason MacFarlane despatched a ‘Most Secret/Private/Most Immediate’ cipher to the War Office, telling them that the Polish goverment were anxious to invite Zhukov to London for discussions. ‘Zhukov is a very big noise, second only to Beria, a prominent figure in Russian secret organisations and has Stalin’s ear.’12

MacFarlane was sympathetic towards Czapski and invited him to the British Embassy to write up his report, which he eventually submitted to the Russians and gave a copy to Mason MacFarlane, who in turn sent it to the War Office and Foreign Office. Frank Roberts, First Secretary of the Central Department of the FO13 made a cryptic remark that the whole affair was very odd and underlined Polish suspicions of the Soviet government.14

The SOE had a desk officer in Moscow who reported regularly to London on the predicament of the Poles in the Soviet Union. The first report, which SOE received from the Poles dated 1 November 1941, came from Buzuluk USSR, one of several centres where soldiers flocked in anticipation of joining the Polish army; others were at Tatischev, Totskoe and Kuibyshev. In accordance with the 1941 Soviet-Polish agreement, they were being released from prisons and forced labour camps scattered throughout the vast Soviet empire. The report by Lieutenant Bronisław Młynarski15 was intended for the Polish government-in-exile based in London. A copy was sent to Professor Stanisław Kot,16 the Polish Ambassador to the USSR (1941–1942) who was temporarily in Kuibyshev, after being evacuated from Moscow with the Diplomatic corps.

Kot had set up an agency, the function of which was to gather information on Poles who were still in Soviet detention. It was staffed by a group of officers recently released, among them Professor Wiktor Sukiennicki.17 Armed with their testimony, Kot would intervene with the Soviet authorities, sometimes not directly informing Anders, who acted similarly. This caused a great deal of friction between them as both claimed primacy of responsibility for the missing. Within the newly formed Polish army in the USSR, Anders had set up Biuro Dokumentów run by Lt Adam Telmany and Lt Gen Kazimierz Ryziński, which was moved to Jerusalem and in 1944 to Rome. By then it was reorganised and renamed Biuro Studiów (Research Bureau) headed by historian Zdzisław Stahl.18

After leaving his post as Ambassador to Russia, Kot became the Minister of State for the Middle East and was in charge of Centrum Informacji of the Ministry of Information and Documentation, which continued to collate information gathered by Biuro Dokumentów.

One of the most important reports – which clearly indicated the journey and final destination of the last deportation of the Polish officers from Kozelsk – was not amongst Kot’s papers. Although not being able to identify the place as Gnezdovo station, the witness saw the prisoners being unloaded from prisoner’s freight cars at a siding on 30 April 1940 and taken away in groups by a bus with blacked out windows. It would return at intervals to pick up the others and take them to a place he thought must be nearby. This secret observation came from Lt Stanisław Swianiewicz,19 Professor of Economics at Wilno University, who was the only one to be separated from the others at Gnezdovo. He was taken to Smolensk prison and from there eventually to Moscow for a trial and sentence of eight years hard labour in Komi District. Swianiewicz was not aware that he was so close to the place of the massacre. In April 1942, he was released from GULag (Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagernie) forced labour camp and eventually reached Kuibyshev to tell the tale. He wrote a short report on 28 May 1942 for Brigadier General Romuald Wolikowski, Military Attaché, which is reproduced below. It still remains a mystery why this vital information did not reach Mason MacFarlane or the Polish government-in-exile any sooner. Was it the fault of an incompetent individual, who failed to register the statement from a civilian witness on the list of officers, or simply forgot to pass the information to the appropriate authorities?

Similarly, Młynarski’s report does not indicate Gnezdovo as a possible place of evacuation for prisoners, but it contained first-hand information on the missing Polish officers and gave precise dates and number of prisoners in each of the three camps who had been mysteriously evacuated to an unknown destination in April and May of 1940. Młynarski asked for help from the British and American governments to impress upon the Russians the need to indicate the whereabouts of these people and to recover them. Historically, Czapski’s concise report, written almost at the same time, tends to overshadow Młynarski’s important document.

Lieutenant Bronisław Młynarski’s Report

Strength of Starobelsk camp

The first batch of prisoners arrived at the camp on 30 IX 1939. About 5,000 other ranks were removed from the camp during October. The winding up of the camp commenced on 5 IV 1940, when the strength amounted to about 3,920, including the sections reserved for Generals and Colonels. This also included over 30 civilians (mostly judges and Government officials) and about 30 officer cadets. The remainder were officers, of whom half were professionals. This included 8 Generals, over 100 Colonels and Lieutenant Colonels, about 230 Majors, about 1,000 Captains, about 2,500 subalterns and about 380 medical officers.

Two other camps, which existed at the same time, were at Kozelsk and Ostashkov. Their strength when wound up on 6 IV 1940 was: Kozelsk about 5,000 men including 4,500 army officers; and Ostashkov about 6,570 men, including 384 Field Police, frontier guards and prison guard officers.

Liquidation of Starobelsk camp

The first group of 195 men were sent from the camp on 5 IV 1940. The Soviet Commandant, Colonel [Aleksandr] Berezhkov and the Commissar [Mikhail] Kirshin, after reading the nominal roll of those to be sent away, declared officially that the camp was to be wound up and its inmates were to be sent to distribution centres from which they were to be repatriated to their domiciles on both sides of the German-Russian frontier. Groups of from 65 to 240 men were sent out daily from the 5th to the 26th of April inclusive, a further group of 200 was sent away on 2 V 1940 and small groups left on the 9th, 11th and 12th May. I left on 12 V 1940 with a group of 16 men. About 10 officers then remained in addition to a few sick officers who were under treatment in the local hospital.

Special groups

After reading a list of about 150 names on 25 IV 1940, the Soviet official declared that he would now read a special roll of 63 names of persons who were to be kept absolutely separate from the rest, during the evacuation of the camp. He repeated this several times, very emphatically. This caused much anxiety in the camp, as no reason for this order was apparent.

Camp at Pavlishchev Bor(nearYukhnov)

After five days of travel, during which we were subjected to the most brutal treatment, the group of 16 to which I belonged arrived at Pavlishchev Bor; the Commandant received us quite well. Here we met the ‘special group’ of 63 men mentioned above. There were thus 79 officers from Starobelsk, including some cadets. If, to this number, we add those officers who were removed from Starobelsk during the first period of our internment there, namely General [Chesław] Jarnuszkiewicz, Colonel [Adam] Koc, Lt Colonel [Jan] Giełgud-Axentowicz, Colonel A[ntoni] Szymanski, Major [Rev.Franciszek] Tyczkowski and Lt W[ładysław] Evert and others it is 85 out of a total number of 3,020, i.e. about 2% of the former strength of these camps.

Griazovets camp(nearVologda)

After about a month the entire camp strength of about 400 was transferred to Griazovets, where they remained from June 1940 until they were liberated. Their living conditions during this period were quite satisfactory. They were joined on 2 VII 1940 by a group of 1,250 officers and other ranks, who had until then been interned in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia.

Conclusions

Two conclusions may be drawn today, from the results of our investigations and from that fact that no word has reached us from over 8,000 officers and many thousands of other ranks who had been interned in Russia. These are:

1. That the Griazovets camp was the only camp existing in Russia for the Polish PoWs after June 1940 and was probably especially created in order to be able to produce a certain number of representative Polish prisoners of all categories, should the need arise at any time.

2. The declaration that they were returned to German-occupied Poland is completely false as nothing is known of them in that part of Poland. Moreover, about half of the prisoners had their homes in Russian-occupied Poland and no word has been received of their fate either.

Since we cannot believe that the Soviet Government does not intend loyally to fulfil the conditions of its agreement with the Polish Government, we can only think that the non-liberation of these prisoners is due solely to technical and administrative difficulties. Should this be the case, could not the Soviet authorities at least inform us of the whereabouts of these men, in order to permit us with the help of the British and American Governments and people to devise some means of rescuing them?

Bronisław Młynarski

Buzuluk, 1 XI 1941

Captain Józef Czapski’s Report

Memorandum on the missing Polish prisoners of war, formerly interned at Starobelsk, Kozelsk and Ostashkov.

The prisoners of war who were interned at these camps from 1939 to April 1940, and who numbered 15,000, including 8,700 officers, have not reported to the Polish authorities, nor do these know anything of their present whereabouts, except for 400–500 persons, or about 3% of the total number of the internees of these three camps, who were released in 1941 from Griazovets near Vologda or from various prisons, after a year’s imprisonment.

CampNo.1at Starobelsk

Parties of prisoners arrived here during the period 30 IX 1939 to 1 XI 1939. The winding up of the camp began on 5 IV 1940, when the strength was 3,920, including 8 Generals, over 100 Colonels, about 250 Majors, 1,000 Captains, 2,500 Subalterns, 30 Cadets and 50 civilians. Over half of the officers were professional soldiers and the prisoners included 380 doctors and many university professors.

CampNo.2at Kozelsk

The strength on the day of liquidation (3 IV 1940) was about 5,000, including 4,500 officers of various ranks and services.

Camp[No.3]at Ostashkov

The strength at the time of liquidation was 6,570, including 380 officers.

Liquidation of Starobelsk camp

The first group of 195 persons was sent away on 5 IV 1940. The Soviet Commandant [Aleksandr] Berezhkov, [in charge of the camp] and the Commissar [Mikhail] Kirshin, [who ‘cleared out’ the camp] officially assured the prisoners that they would be sent to a distribution centre from whence they would be taken to their domiciles in German and Soviet-occupied Poland. We know with absolute certainty from numerous letters received from Poland during the winter of 1940-41 that up till now, not one of the former internees of the three camps in question has returned to his home in Poland. Up to 26 IV 1940 inclusive groups from 65 to 240 persons were sent from the camp. On 25 IV 1940 a group of over 100 persons were instructed to get ready to leave, after that a special roll of 63 names was read; these persons were to constitute a separate group during the march to the railway station.

The next party of 200 left the camp on 2 V 1940 and the remaining prisoners left in small groups on May 8th, 11th, and 12th. The last group was sent to Pavlishchev Bor (Smolensk district), where they joined the special group of 63 sent from Starobelsk on 25 IV 1940. There were thus 79 officers from Starobelsk at this camp and they were released from Griazovets in 1941. In addition seven officers who had been taken from Starobelsk to various prisons were released. The total number accounted for is thus 86, being just over 2% of the total strength of 3,920.

Liquidation of the Kozelsk and Ostashkov camps

This was effected in a similar way. The camp at Pavlishchev Bor contained 200 officers from Kozelsk and about 120 persons from Ostashkov; these figures represent about 2% of the respective strength of these camps.

Griazovets camp

After a month’s stay at Pavlishchev Bor, the inmates, numbering about 400, were transferred to Griazovets near Vologda. To this camp were also sent 1,250 officers and other ranks who had previously been interned in the Baltic Republics and who had been kept as internees (not prisoners of war) in no.2 camp at Kozelsk, from the autumn of 1940 to the summer of 1941.

The Griazovets camp is the only camp containing a majority of Polish Army officers known to us to have existed in the USSR from June 1940 to September 1941. Practically the entire strength of this camp is now part of the Polish Army in the USSR.

Six months have now elapsed since an amnesty was proclaimed for all Polish prisoners of war and other prisoners on 12 VIII 1941. Since that date, a steady stream of officers and other ranks of the Polish Army have been reporting to their H.Q. from various camps and prisons. In spite of the proclamation of this amnesty, notwithstanding the categorical promise that our prisoners of war would be released, made by the Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, M. Stalin to H.E. [His Excellency] Ambassador Kot on 14 XI 1941 and in spite of the categorical order given by Stalin in the presence of Generals Sikorski and Anders on 3 XII 1941, that the former inmates of the camps in question should be sought out and released, not one of them has yet returned (with the exception of the Griazovetz group). Nor has any communication as yet been received from any of these prisoners.

Interrogation of thousands of prisoners released from very numerous prisons and camps has not elicited any trustworthy information as to the location or fate of these prisoners, except for reports received at second hand. These are:

a. Six to twelve thousand officers and NCOs were sent to Kolyma via Bukhta Nakhodka in 1940.

b. Over 5,000 officers were sent to the mines of Franz Joseph Land.

c. That they were sent to Novaia Zemlia, Kamtchatka and Tchukotka; that during the summer of 1941, 630 officers from Kozelsk were working 180 kilometres distant from ‘Piostroy Dzesva’, that 150 men in officers’ uniforms were seen to the North of the Soava River, near Gari, that Polish officer PoWs were taken in huge barges drawn by tugs (1,700–2,000 men per barge) to the Northern Islands and that three such barges sank in the Barents Sea.

Not one of these reports has been confirmed, although those suggesting Kolyma and Northern Islands seem to us to be the most probable.

We know how carefully the registration of each prisoner was conducted, and how the dossier of each prisoner, complete with questionnaires, interrogations, photographs, etc., was kept in a special file and we know with what meticulous care all the records were kept by the NKVD. We cannot for these reasons believe that the present location of 15,000 prisoners, including over 8,000 officers, is not known to the higher authorities of the NKVD.

In view of the solemn promise made by M. Stalin, and of his categorical order that the fate of the prisoners should be elucidated, may we not hope that we shall be informed of the present whereabouts of our comrades, or, if they are no longer alive, at least that we should be told where they died and in what circumstances they lost their lives.

Number of officers missing:

Total strength of Prisoners of War at Starobelsk on 5 IV 1940 (excluding 30 cadets and 50 civilians)3,820Total strength of the Kozelsk camp on 6 IV 1940 was 5,000 (including officers)4,500Total strength of Ostashkov camp on 6 IV 1940 was 6,570 (including officers)380Total8,700Reported to the Polish Army from Griazovets and various prisons500Total missing officers from Starobelsk, Kozelsk and Ostashkov8,200All of the present officers of the Polish Army in the U.S.S.R. on 1 I 1942, numbering about 2,300, are ex-internees from the Baltic countries, but are, with the exception of the above mentioned 500, not ex-prisoners of war.

It is impossible for us to present an exact estimate of the number of such prisoners still missing, excluding the case of the three officer camps under discussion. In accordance with the decision made by M. Stalin and General Sikorski, the strength of our Army in the U.S.S.R. has been increased. As a result the need for these officers is being felt increasingly urgently, the more so as these were our most highly qualified military specialists.

Moscow, 2 February 1942

Czapski would not have known that amongst the 4,500 prisoners at Kozielsk – which held four generals, one admiral, about 100 colonels and lieutenant colonels, 300 majors, 1,000 captains, 2,500 lieutenants and second lieutenants and over 500 sergeants – that there was one woman officer, Second Lieutenant of the Polish Air Force, pilot Janina Lewandowska, daughter of General [Józef] Dowbór-Muśnicki. She had married pilot instructor Lt Col Mieczysław Lewandowski in the summer of 1939. He managed to reach France, then England, to serve as an RAF pilot. She was shot down over Russian territory in September 1939 while in action and was taken to Kozelsk camp. According to statements of those who survived, she had a separate room and was often castigated by the NKVD guards for attending forbidden religious meetings. Her two airmen friends, with whom she was in close touch, were on an earlier list of the condemned to be evacuated into the unknown and she confronted the guards beseeching them to take her as well. A few days later, dressed in male uniform, pilot Janina Lewandowska joined her dead friends in the Katyn woods.20

With Czapski’s report, which was probably translated at the British Embassy, Mason MacFarlane transmitted his own ‘Most Secret’ observations to Major General Davidson in London, about the missing officers:21

There is not the slightest doubt that the NKVD must know what has happened to these Poles as the most detailed nominal rolls and information are kept up at every concentration camp and prison … I am in close touch with Czapski but propose to keep us out entirely of this business, which is a purely Polish-Russian affair …

The NKVD is clearly going back on the categorical assurances given by Stalin to Sikorski. My personal opinion is that nothing short of a personal communication from Sikorski to Stalin will produce results. I send you this only to keep you and COS [Chiefs of Staff] in the picture. The question is a domestic one between the Poles and Russians and I don’t think we ought to get mixed up in it.

The Foreign Office Comments

Others in the Cabinet and Foreign Office quickly picked up this argument. The obstacle lay, amongst other issues, with an unwillingness to help Ambassador Kot, who, while asking Clark Kerr for intervention, was known to have openly criticised the Anglo-Soviet Treaty, which was obviously detrimental to Poland’s future. In consequence, the War Office advised Clark Kerr not to be too accommodating toward the Polish Ambassador. Frank Roberts, head of the Central Department grudgingly gave his support, while others declared that supporting the Poles would not make much difference – except to irritate the Russians. And on top of that, Kot had been talking ‘poisonous stuff’ about the Anglo-Soviet Treaty. Prior to being seen by Anthony Eden,22 the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and Sir Alexander Cadogan,23 the Permanent Under Secretary of State, had the last word: they should not link the two matters but base the refusal on the grounds that the British government could not exert sufficient influence on the Russians. Eden agreed and annotated with his usual red ink: ‘Yes, let Kot see the link, rather than point it out to him.’ On May 1942, Sir William Strang,24 the Acting Under Secretary of State, Central Department of the FO, sent Ambassador Sir Archibald Clark Kerr an ‘immediate decipher yourself signal’ with just that advice:

I should prefer you not to intervene in this Russo-Polish question. Our intervention might only serve to irritate the Soviet Government. You should base your refusal on this ground and on our inability at present to exert sufficient influence with the Soviet Government but without directly connecting the two questions, you may be able to let your Polish colleague see that he is unlikely to obtain much satisfaction on this issue while he continues to criticise the Anglo-Soviet negotiations so openly.25

The British, in spite of opportunities to do so, did not raise the matter again, while the Polish government remained unable to elicit the truth from the Russians without British assistance.

Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Hulls’ report

The three reports written for the War Office by British Liaison Officer Lieutenant Colonel Leslie R. Hulls26 have survived. The first, dated 18 June 1942, was sent from Yangi-Yul, a place near Tashkent, the HQ of the Polish Army in Uzbekistan. The other two came from Quisil Ribat, dated 29 October and 3 December 1942. Hulls had witnessed the miserable condition of the Polish Army and pleaded with the British military authorities to put pressure upon Stalin to adhere to the agreement and release the rest of the missing officers.

Hulls must have written a number of reports to the Military Intelligence Department of the War Office. The follow-up briefs indicate that Hulls’ personal experience and knowledge of the Russians were ignored. The subject of his report of 3 December 1942 can be verified by the Soviet documents released between 1992 and 1997 to the Polish Committee of Military Archivists in Warsaw.27 Hulls’ verbatim reports are difficult to follow owing to their peculiar grammatical structure. In the interest of clarity some of his grammar and vocabulary has been amended; but the tone and factual content has not.

Polish Soviet Relations

The Soviet note to the Polish Government dated 31.X.1942 regarding the military agreement and the refusal of the Soviet Government of a further recruitment in Russia.

1. Said document deals with two questions:

a. It intends to show the good will of the Soviet Government towards Poland concerning the military agreement of August 14 1941.

b. It intends to justify the refusal of the Soviet Government of further recruitment of Polish soldiers in Russia.

There is little truth in this document and in general it gives a completely false picture of the situation.

Notwithstanding its length, the contents of the Soviet note can be brought down to this one statement: the Poles have refused to send the 5th Division totheRussian-Germanfront,in consequence of which the Soviet Governmentnow refuses to allow a further recruitment of Polish soldiers in Russia. Although at this point, the Note mentions loosely the Polish Army and ‘Polish Division’ there was no question whatever of any other division besides the 5th, which was to get ready to go to the front. The 6th Division which was to be formed had, not even for training purposes, neither motorized vehicles, nor artillery, nor was it in possession of machine-guns or with liaison and engineering implements (I state it here on the basis of my personal observations). In connection with the above, the Soviet General Staff had communicated to the Polish Staff in September 1941 that the situation on the front did not allow for the equippingof a second Polish Division.Stalin had promised to settle this in December 1941,but in spite of this,up to the summer of 1942 the situation had not altered.

In my position as an independent observer who has been a witness to all these events, I try to represent all that has happened in the light of truth and with objectivity. In brief, the whole question can be summarised as follows.

The Polish-Soviet agreement of July had been completed by a military agreement on August 14 1941. The basis of this agreement was that a Polish Army was to be created in Russia, the recruitment of said army was to be made among the Polish officers and soldiers deported and imprisoned in Russia. The strength of the army had not been defined and thus the affirmation contained in the Soviet note that said army was to consist of 30 thousand men is not true. There has been no mention, either in writing or in any other form, of such a question being asked. The manpower of the army had been defined for the first time during General Sikorski’s visit to Moscow in December 1941 and had been already then been fixed as 96,000, 25,000 more were to be transferred to the British Empire and … there would have been more manpower suitable for military service; the figure of 96,000 was to be increased with a further division of 11,000 men.

Officers and soldiers started presenting themselves in September. In December about 40,000 were called and enlisted in the ranks, in March 1942 the figure of 70,000 had been reached. In February, the Army, with the aim of avoiding the consequences of the winter, had been transferred from the Samarkanda region to Uzbekistan. The soldiers were located in cells in a temperature of 45 degrees below zero. As I have already mentioned, these people were coming to the Army from prisons and penitentiary camps. They never had been treated as prisoners of war, as a consequence of which they came out of prison with damaged health.

For an army at this stage of organization, the food rations were inadequate, even for a healthy man, and so the problem of restoring the sick soldiers to health was pressing up to the last moment, until the evacuation of the Army from Russia.

A number of food rations had been sent from England through Archangelsk and were being used for supplementary feeding of the sick, of the convalescents and for those employed in heavy work. Exhaustion caused by denutrition [sic] and lack of vitamins amounted to 14%. It was a common occurrence for soldiers during night manoeuvres to be returned to their quarters because they were afflicted by nyctalopis [sic; nyctalopia, night blindness].

Armament and Equipment

In the beginning, England and the US had undertaken the task of equipping the Polish army on the condition that the troops would be transferred to a place where the said task would be convenient and easy. One thought at the time was India; the Soviet Government did not give its consent for the army to leave Russia. The Russians agreed then to equip two infantry divisions, while the English continued to attempt to equip and arm the whole of the rest of the Army.

In the spring of 1942, the Russians had partially armed one division, the 5th. Still, the armament was greatly lacking, there was a deficiency in particular of motorised vehicles, machine guns, mortars, anti aircraft batteries and tanks. The whole artillery was limited to just 16 field guns. The armament specification of the 5th Division is herewith included. The remaining divisions and the Army as a whole were, rifles excepted, quite without arms. The uniforms had been sent from England.

The Soviet Government in their note insist on the fact that the Polish Command … has not prepared to a level of readiness one division by the date of 1.X.1941. No Soviet Staff officer had ever declared seriously that it was possible to form even one division for that date. Whether this had been previously established or not, is an irrelevant question as the responsibility in this regard is borne by both parties. The Russians on their side had not furnished the armament, neither for the date of X.1941 nor six months later, but nobody can blame them for it, considering the conditions and the general situation. As to the Poles, considering the fact that the first soldiers started arriving only in September they were certainly not in a postion to organize a division for 1.X.1941. In the Soviet note pt 3, this aspect of the question is only partially acknowledged.

The fact that six months later the 5th Division was still unarmed and unprepared for the fighting, can be explained only and exclusively by the lack of armament, for which the responsibility falls upon the Soviet Government.

In February 1942 the Soviet authorities proposed to General Anders sending to the front the first two divisions when their armament was completed. The General refused to send these units to the front without previously training them to handle the arms that they were to use.

Referring again to the Soviet note:

Pt.1 underlines that the Soviet Government showed the maximum good will and energy in forming a Polish army in Russia. On the contrary, the soldiers came out of the penitentiary camps in rags and were without clothes until the uniforms arrived from England. The food rations were quite insufficient in quantity and quality. (Russia in that period was only after eight months into the war). The authorities were refusing all information concerning the locationsof officers and soldiers.Considerable numbers of Polish officers have not beenfound.Those imprisoned in Kozelsk,Starobelsk andOstaszkowo[Ostashkov]simply disappeared without any trace(8,300altogether). Nobody has heard of any of them since 1940 and notwithstanding the promise given personally by Stalin to General Sikorski and General Anders, the fate of these officers remained a complete mystery.

Pt.2 underlines the friendly attitude of the Soviet Government in their consenting to fix the number of the Polish soldiers at 96,000. Why this is alluded as a positive point, for the Soviets remains quite incomprehensible. It was the desire of the Poles to fight again and in consequence to organise the greatest possible army. This was to the advantage not only of Russia but also of all the Allied nations.

Pt. 3 underlines the difficulties of provisions and the measures taken to increase the rations of the fighting soldiers at the expense of the non-combatants. The Polish Army has of course been defined as being in the second category. The Note continues, stating that it has been decided to diminish the number of rations for the Polish army to to 44,000, the remaining troops, requested by the Polish Government, are to be evacuated to Persia. Nobody intends to contest the decision of the Soviet Government to consider the Polish army as non-fighting, but leaving 30,000 soldiers without food rations could have only one result, namely said detachments would have to be transferred to another place where they would be fed and equipped.

The remaining part of the said paragraph is completely false and would not convince anyone. Concerning the second evacuation to Persia, it should be remembered that for four months the Soviet Government steadily refused to accede to this evacuation, although on their part, literally nothing had been done to arm the remaining 44,000. The Soviet authorities even went so far as to inform our [No.30] Military Mission in Moscow that the evacuation bases at Pahlevi [port] in northern Persia should be shut down as no further evacuation would take place (telegram addressed to Troopers at the Military Mission in Moscow No 6132 dated 30 VI 1942).

The Soviet authorities were not able to give any justification for their refusal to transfer the Polish army to a place where the troops could have been armed and equipped. As it was becoming increasingly obvious to all the Allies that this solution was the only possible one, we decided to become involved. Quite unexpectedly, on 27 July, without any explanations, the Soviet Government consented to the evacuation.

Pt. 4. The Polish Government, whilst considering it impossible to restore the Polish soldiers in Russia to a state of physical fitness and to equip and arm them, was now making an effort to transfer these troops to a place where all this could be done. In this endeavour the Polish Government wanted to help the Allies. The Polish Government was following, to the best of its understanding, the intentions of the Polish Soviet agreement: ‘the creation of a Polish army to fight by the side of Russia and of the Allies against Germany’ (see pt.1 of the Soviet note).

The question of further recruitment in Russia

The refusal demonstrates the disposition of the Soviet Government towards Poland. This refusal is expressed clearly in the Soviet note. It is contrary to the interests of the Allies. It is difficult to believe that not sending one Polish infantry division of 11,000 soldiers (even if said division were fully prepared for fighting) to the Russian front could become the cause of an international misunderstanding, as is actually the case.

If anyone is unconvinced, I stress the point again:

a. Did the Soviet Government attach any real importance to the immediate forwarding of the 5th Division to the front?

b. Was the 5th Division effectively armed and equipped?

It will perhaps be sufficient to quote here some of the conversation between General Anders and Stalin that took place on the 18. III. 1942: discussion of the matter of reducing the quantity of food rations (the Soviet Government had fixed the limit of rations to 20,000 soldiers) and of transferring half of the army to Persia, a logical consequence of that reduction, and lastly, on the matter of the part to be played by the remaining army in Russia. Stalin in conclusion said: ‘All right,I consent to assign44,000rations.This quantity willbe sufficient for three divisions.You will have time enough for drilling,we do not insist on your speedy appearance on the front.It will be better for you tostart when we are nearer the Polish frontiers.You should have the honour toenter Polishlandfirst.’

At the end of the conversation, General Anders said to Stalin: ‘To save time I should like to discuss all the technical details with General [Aleksei] Panfilov if you authorise him to do this.’ Stalin replied ‘Good, these matters will be settled by General Panfilov.’ On the next day, that is 19 March, General Anders met with General Panfilov (Head of the Russian General Staff) and during the discussion on the evacuation and on the equipment of the troops remaining in Russia, General Panfilov said ‘Tomorrow we will arrange for the completion of the armament ofthe 5th Division and the furnishing of arms also to the 6th Division.’

Pt. 5. I hope that in the name of truth the above facts are sufficient to frustrate the attempt made in the Soviet note to give a completely false picture …

One could ask here what is behind this attitude of the Soviet Government. As already underlined in my previous reports, the Soviet Government had never fulfilled the agreement signed with Poland, neither from the military point of view nor in those matters that concern the civilian population. Far from helping in the formation of a strong Polish Army, the Soviet Government tended to divide it. In the first place the initial 70,000 have been divided in two parts. When such a situation could no longer be maintained, the Soviet Government cut away a great number of Polish soldiers from the Army in Iraq.

There are no reasons to refuse these soldiers the opportunity to enlist in the army. On the contrary the Polish army needs them badly and the Polish Government demands them. In this matter the Polish Government looks for our help.

L R Hulls

Professor Stanisław Swianiewicz’ Declaration

From the beginning of November 1939 until 29 April 1940, I was a prisoner of war in Kozelsk camp. From the beginning of April, the camp was slowly liquidated by removing groups of people 200 to 300 strong to an unknown destination. The camp authorities tantalised us for some time that soon we were to be sent home. The group I was assigned to was the last one to leave.

On 29 IV 1940, we were loaded into railway carriages adapted to carry prisoners [Stolypinki].28 The walls were covered with messages, something like: ‘returning home is a lie, they are taking us to another camp.’ In the morning of 30 IV 1940, we passed Smolensk, and a dozen or so kilometres beyond Smolensk we stopped. It appeared that we were to detrain. Presently an NKVD officer came in with information that I was to be taken out of the convoy and placed separately in another railway compartment. From the narrow top slit of the compartment I could observe the area, which was well guarded by the NKVD. My compatriots were unloaded and put into buses with blackened windows. The bus would return empty to pick up others after an interval of about half an hour. From this scene I gathered that my colleagues were being taken to another camp not far from the railway station. After this movement of men had finished, I was taken separately by car to Smolensk prison and soon afterwards I was transported to Moscow.

From that moment I have lost all contact with my comrades in distress with whom I stayed in Kozelsk camp, with one exception, that is in February 1941 while in Butyrki prison in Moscow, I met Captain [Janusz J.] Makarczyński of DOK (Dowództwo OkręguKorpusuLublin - General Staff, Lublin Corps), who was deported from Kozelsk camp on his own, as far as I remember, before April 1940.

During my stay in various prisons and GULags, I used to hear fragments of information about the Polish PoWs in Northern Russia:

1. Towards the end of 1940, in the Lubyanka prison, a Russian prisoner had told me that previously, he met and sat in prison with a Polish NCO who was brought from Komi GULag, where in 1940, he worked on road repairs and said that conditions were bearable.

2. In March 1941 I met another Russian from Kotlas camp, who in the summer of 1940 worked in Uhta in the Komi region, extracting radium. He too, saw a large group of about 200 PoWs, marching in a northeastern direction. He was told that all of them were Polish officers.

3. While staying in various camps and GULag posts north of Kniazpogost between March and April 1942, I have seen small groups of soldiers in uniform near a railway station at Josser but the guards did not allow us to make contact. By the style of some uniforms, I gather there must have been some Poles amongst the officers and men marching to work; another guard has confirmed it. At a place called Ropcha, 8 kilometres north of Josser station, there was a hospital belonging to Sievzeldorlag district, where sick people from the camps were sent. There was a cemetery with Polish graves nearby, showing clearly the names and ranks of the dead. This particular PoW camp was closed down in the summer of 1941.

4. In February 1942, at the 14 Ustvim GULag while in hospital, I was told by another Russian that in the summer of 1940, he was doing hard labour in the region of Murmansk and saw large movements of Polish soldiers. I was told the life in these camps was exceptionally hard and by observations it can be assumed that they were Polish officers.

Stanisław Swianiewicz29

Kuibyshev, 28 May 1942

Notes

1 Lavrenty Beria (1899–1953) in 1939 Commissar General of the Internal Security NKVD (Narodny Komissariat Vnutennikh Diel) of the USSR, member of the Politburo and a close friend of Stalin. He was instrumental in submission of a resolution on 5 March 1940 to shoot the Polish PoWs. After Stalins’ death Beria was charged with ‘anti state’ crimes and was executed on 23 December 1953.

2 Pyotr Karpovich Soprunenko (1908-1992) Soviet Security official NKVD, close to Beria, head of PoW administration (1939-1944). Supervised ‘clearing out’ of the three camps. In 1990, identified as a witness to the massacre.

3 Joseph Stalin (Iosif Vassarionovich Dzhugashvili) (1879-1953). Born in Georgia, member of Lenin’s Bolshevik Party (1903–1917), party bureaucrat and Soviet leader (1928-1953). Introduced wholesale purges and crimes against his own people, created the GULags; responsible for the massacres of the Polish PoWs. Considered by the Russians as a man of steel, who led them to victory and domination over Eastern Europe; denounced by his accomplice Khrushchev in 1956 and by the last president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, in 1990.

4 Katyn. Dokumenty Zbrodni, Jeńcy nie wypowiedzianej wojny, 23 sierpień 1939 – 5 marca 1940 (Katyn, Documents of Crime, Prisoners of Undeclared War, 23 August 1939 – 5 March 1940), published jointly by Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych (Directorate of The National Archives) in Warsaw and The National Archival Services of Russian Federation GARF (Gosudarstvenny Arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii) and the Central Security Service Archives of the Russian Federation FSB RF (Federalnaia Slusba Bezopasnosti FederatsiiRossiiskoi) in Moscow. Editorial Committee under Aleksander Gieysztor and Rudolf Pikhoia, editorial work Wojciech Materski, Natalia Lebedeva and others. Warsaw 1995, Vol I, p.7-55, docs. 188, 216; Vol II docs. 87, 95; Vol III doc68; Vol IV docs. 197, 207, 208, 212, 221. Translated copies of the NKVD documents in four volumes, selected by the Russian and Polish historians between 1993 and 2005.

5 Władysław Sikorski (1881–1943). Polish General and statesman, took part in 1920 War of Independence against the Bolsheviks, Chief of General Staff, Premier and War Minister till 1925. Spent thirteen years in opposition. In 1939 escaped the German invasion via Rumania to France, formed a government in Paris, after its fall moved to GB together with armed forces, set up a coalition government in exile as its Prime Minister and Commander in chief. Died in plane crash off Gibraltar, 4 July 1943.

6Katyn Dokumenty Zbrodni…Vol III document 217, Fedotov report 3 December 1941.

7 Władysław Anders (1892-1970), General, served as a young officer in the Tsarist army during the First World War, later joined the Polish Army and fought in 1920 War of Independence against the Russians. In 1939 commanded a cavalry brigade, wounded and taken prisoner by the Russians and held at Lubyanka prison in Moscow. Released after the Soviet-Polish Agreement of 14 August 1941. Commander of a newly formed Polish Army in USSR from thousands of Poles released from Russian imprisonment. Commander in Chief of 2 Polish Corps (under command of the British Eighth Army) who led the Poles to victory at the battle of Monte Cassino in Italy. After the Polish Forces were disbanded in 1946, remained in exile as a prominent leader of the ‘free’ Poles. Wrote memoirs, Bez Ostatniego Rozdziału (Without the Last Chapter) 1949.

8 Frank Noel Mason MacFarlane (1889–1953) Lt Gen. RA, served in Africa and India, Staff Capt. WWI, Afghan War 1919, GSO1 in India 1922-5, Staff officer 1928–30 in India, Military Attaché Budapest 1931–5, Vienna, Berne then Berlin 1937–39, Head of Military Mission in Moscow 1941–2, Governor of Gibraltar 1942–44, Chief Commissioner of Allied Control Commission in Italy 1944, awarded Polonia Restituta 1st class, retired 1945, became an MP.

9 TNA WO 32 /15548, a self-typed report by Lt Gen Mason MacFarlane, head of 30 Military Mission in Moscow, dated 7 August 1941.

10 Józef Czapski (1896–1993) Cavalry Captain in reserve, 8 Lancers Division, born and raised in Moscow of aristocratic family, accomplished painter who studied in Paris, survivor of Starobelsk camp. After the war published among other pieces Wspomnienia Starobielskie (Starobelsk reminiscences) Rome 1945 and Na nieludzkiej ziemi (Inhuman Land) Paris 1949.

11 Vselevod Nikolaevich Merkulov (1895–1953). Soviet Security official, aide to Beria specialising in cruel interrogation, member of Troika appointed 5 March 1940, to exterminate the Polish officers. In charge of ‘clearing out’ the three camps. Arrested with Beria and executed in 1953. Named with Beria in 1990 as responsible for murdering the Polish PoWs in 1940.

12 TNA HS 4 /243 Most Secret cipher telegram sent from No. 30 Military Mission in Moscow to the War Office DMI, MIL 681, 8 September 1941.

13 Frank Kenyon Roberts (1907–1998), started his diplomatic career as Third Secretary in the FO in 1930, served in Paris 1932, Cairo 1935, transferred to the FO in 1937; First Secretary in 1940, acted as Chargé d’ Affaires in Czechoslovakia; war years in FO as Head of Central Department, Chargé d’ Affaires in Moscow 1945–7; Principle Private Secretary, Assistant Under Secretary of State in 1949; High Commissioner for India in 1951, Deputy Under Secretary of State German Affairs; Ambassador in Moscow 1960–2 and Bonn 1963–8. Knighted. Dealing with Dictators, autobiography published 1991.

14