18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

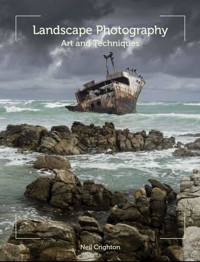

Every continent, country and region in the world has magnificent landscapes to photograph. Every season, climate and time of day has its own unique quality. This practical book describes how best to look at a scene and work with the elements within it to produce images that really encapsulate those elements and describe in visual terms the expanse, depth and beauty of a place. Explains how a digital camera produces a good landscape photograph, advises on themes, composition, selection, lighting and the use of software in the digital darkroom, and is illustrated with stunning photographs that show how the elements within a landscape, the changing seasons and the light combine to give the scene its feel and emotive quality. Aimed at photographers, travellers and journalists, and superbly illustrated with 213 stunning colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Landscape Photography

Art and Techniques

Neil Crighton

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2012 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Neil Crighton 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781847978486

Acknowledgements

In writing this book, I am sharing with you the experience I have gained in my career as a photographer and lecturer that has so far lasted 42 years. I consider myself lucky to have had the opportunity to visit and experience some of the wonderful locations around the world and meet some fascinating and inspiring people on my journey.

My appreciation for additional photos goes to Enrique Fernandez Redo, Andreas Fernandez Rosenke, Nina Fernandez Rosenke, Alasdair Crighton and Julia Crighton and for their generosity in making them available to me.

None of this would have been possible without the support of my wife Julia, for her painstaking editing and assistance, and our children, Fraser, Beatrice and Alasdair, who waved me off on my journeys and never complained about my long absences away from home. Thank you.

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

1 Your Camera

2 Choosing Your Subject

3 Using Light and Depth

4 Viewpoint and Atmosphere

5 Composition

6 What Determines a Good Landscape?

7 Using Time and Motion

8 Coastal Scenery

9 The Landscape at Night

10 Processing Techniques

11 Travelling with Your Camera

Glossary

Further Information

Further Reading

Index

Winter moon.

Foreword

‘Two of the most frustrated trades are dentists and photographers,’ Picasso once said. ‘Dentists because they want to be doctors, and photographers because they want to be painters.’

Like all good aphorisms, this is completely bogus. The painter himself didn’t believe it. The inspiration for Cubism arguably came from some distorted images taken on his friend Severini’s broken camera and, in any case, Picasso also announced: ‘I have discovered photography. Now I can kill myself. I have nothing else to learn.’

Discoverers of Neil Crighton’s work in the generously illustrated pages of this important new volume will not be rushing to follow Picasso’s lead. For one thing, we have plenty to learn and this is just the book to teach and inspire us.

This is much more than a how-to manual. In his engaging introduction, Neil traces the line of descent of landscape art to its early fifteenth-century origins, and the early croszcfertilization of art and photography with camera obscura and lucida – a glass prism on an adjustable metal arm fastened to the artist’s drawing board, which refracted a traceable image on paper.

There was the usual grumbling about photography killing art, of course (just as video would kill the radio star, and Kindle the printed book). Charles Baudelaire, reviewing an 1859 photographic exhibition said:

‘If photography is allowed to supplement art, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether.... If it is allowed to encroach upon the domain of the... imaginary, upon anything whose value depends solely upon the addition of something of a man’s soul, then it will be so much the worse for us.’

A flick through some of the extraordinarily atmospheric photographs in this book shows how misplaced these fears were.

Far from being a frustrated painter, Neil’s photographic calling came early. His own personal development grew from school science lessons – ‘for me, the whole magical process of photography then was a continuation of the study of chemistry and chemical reactions applied to a creative purpose’ – to experiments with his father’s 35mm Kodak Coloursnap, a secondhand Zenit, and a prized Asahi Pentax SV.

Usefully for any photographer hoping to make a living from the business, his own career route, from positions with the National Physical Laboratory and Portsmouth Polytechnic, to a globetrotting role with ICI/Zeneca took him to fifty-six countries, and ultimately to his own business. He now lives with his wife Julia in northern Sweden, where he has converted an old church into a photographic gallery and school of photography.

Throughout, Neil’s infectious enthusiasm and passion for his subject, and his subjects, shines through. Enjoy.

Richard Lomax,Journalist and Director:Redhouse Lane Communications Ltd.(London and Glasgow)

View of Stockholm through a window.

Introduction

Painters began to include nature in their work during the fourteenth century, introducing elements of the landscape as the background setting for the figures in their paintings, which were invariably ‘religious commissions’ depicting important religious figures or biblical characters in an allegorical setting.

Landscape painting was established as a genre in Europe early in the fifteenth century, portrayed as a setting for human activity, yet still often expressed within a religious context. Landscapes were idealized, mostly reflecting a pastoral ideal drawn from classical poetry which was first fully expressed by Giorgione and the young Titian, and remained associated above all with a hilly wooded Italian landscape, depicted by artists from Northern Europe, many of whom had never visited Italy. Joachim Patinir developed a style of panoramic landscapes with a high viewpoint that remained influential for a century, and was further used by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. The Italian development of graphical perspective allowed large and complex views to be painted very effectively.

The term landscape was not used until the sixteenth century. It was borrowed from the Dutch painters’ term landschap, meaning region, or tract of land, but when brought into the English language it had acquired a newer artistic sense as ‘a picture depicting scenery on land’. The seventeenth century saw the dramatic growth of landscape painting, particularly in the Netherlands, in which extremely realistic techniques were developed for depicting light and weather.

In England landscape painting was considered a minor branch of art until the late eighteenth century, when the Romantic spirit encouraged artists to raise the profile of landscape painting. William Turner, known as ‘the painter of light’, employed watercolour landscape painting techniques to his use of oil paints to create a unique style of light and atmosphere for his land- and seascapes. Initially he toured England and Scotland, and later in his career travelled widely in Europe to Germany, Holland, Belgium, France, Italy and Switzerland.

Turner’s Romantic style gradually gave way to a style that was to become even more widely recognized, developed by the French. From the 1830s Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and other painters in the Barbizon school established a landscape tradition that would become the most influential in Europe for a century, with the impressionists and post-impressionists making landscape painting for the first time the main source of general stylistic innovation across all types of painting.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE CAMERA

The artist David Hockney and physicist Charles M. Falco have suggested that advances in realism and accuracy in painting and drawings in western art were primarily the result of optical aids such as the camera obscura, camera lucida, and curved mirrors, rather than solely due the development of artistic technique and skill.

The camera obscura was a small wooden box with a lens at one end that projected the scene before it onto a piece of frosted glass at the back, where the artist could trace the outlines on thin paper. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many artists were aided by the use of the camera obscura. Jan Vermeer, Canaletto, Guardi, and Paul Sandby are but a few.

The camera lucida was an adjustable metal arm fastened at one end to the artist’s sketchbook or drawing board and used a glass prism at the other end, the refracted image of the subject or landscape would be superimposed on the paper – it was then a simple task to trace the features with a pencil. By the beginning of the nineteenth century the camera obscura was adapted, with little modifications, to accept a sheet of light-sensitive material, to become the photographic camera.

In France Louis Daguerre had been searching since the mid-1820s for a means to capture the fleeting images he saw in his camera obscura. He formed a business partnership with Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who had been working on the same problem – how to make a permanent image using light and chemistry – and as early as 1826 had achieved primitive but real results. In 1839 Daguerre revealed his daguerreotype process, in which a one-of-a-kind photographic image was produced on a highly polished, silver-plated sheet of copper, sensitized with iodine and exposed in a large box camera. The image was then developed in mercury fumes and fixed with ‘hypo’ sodium thiosulphate, which is still used to fix black and white films and paper. Daguerre used the process to record static subjects and Parisian views.

A simple diagram showing how a camera obscura works.

In 1840 William Henry Fox Talbot, British inventor and a pioneer of early photography, produced a negative image that could be used to make positive paper prints. He discovered that an exposure of seconds, leaving no visible trace on a chemically treated paper, left a latent image that could be brought out with the application of a solution of gallic acid. This process, called calotype, opened up a whole new world of possible subjects for photography.

Fox Talbot wrote and illustrated The Pencil of Nature, the first commercially published book illustrated with photographs. It was published in six instalments between 1844 and 1846, containing twenty-four salted paper prints from paper negatives that were carefully selected to demonstrate the wide variety of uses for photography, including landscapes. He also made major contributions to the development of photography as an artistic medium.

Not only did this new process allow people to document their family and loved ones, but also to provide images of distant lands. The custom of the Grand Tour, which was undertaken by mainly upper-class European young men and women of means, served as an educational rite of passage and was documented at first by diaries, sketches and drawings and then later by photography. Francis Frith, a successful studio photographer and founding member of the Liverpool Photographic Society, travelled to the Middle East on three occasions in the mid-1850s, with very large cameras (16" × 20").

Urban cityscape (central Stockholm).

According to Frith, ‘the difficulty of getting a view satisfactorily in the camera: foregrounds are especially perverse; distance too near or too far; the falling away of the ground; the intervention of some brick wall or other common object... Oh what pictures we would make if we could command our point of views.’ He set himself a huge photographic project, to document every town and village in the United Kingdom, in particular the notable historical or interesting sights. Initially he took the photographs himself, but as success came, he hired people to help him and set about establishing a postcard company.

LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHERS

Landscapes, their character and quality, help define a region or area, to differentiate it from other regions. Landscape comprises the visible features of an area of land, including the physical elements of landforms such as mountains, hills, rivers, lakes and the sea; the living elements including vegetation; human elements including land use, buildings and structures; and transitory elements such as lighting and weather conditions. Photographers have always been inspired by land formations and natural wonders, such as vast forests, canyons, mountains, deserts, lakes and waterfalls.

English photographer Roger Fenton remained in the tradition of a stereotypical picturesque tourist Victorian postcard style, creating idealistic views of the landscape which closely copied the previous work of painters. Peter Henry Emerson pioneered a movement based around ‘naturalistic’ photography, which was the opposite of the contrived and sentimental style of painting. The pictorialist movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century established photography as a fine art in its own right, taking on board different processes and techniques, such as blurred details in landscapes and cropping. Even impressionist painters looked towards photographic cropping to produce unusual images. Japanese art also had its influences in a strong and sometimes simplistic graphic style of photography.

Urban cityscape (Glasgow).

In the American West the Union Pacific Railroad used photographer Andrew Joseph Russell to document the railway’s progress from 1868 to 1869. William Henry Jackson’s photographs helped to create the American National Park system, beginning with the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872. Edward Muybridge, who took up photography in the 1860s, learned the wet-collodion process and used it to focus principally on landscape and architectural subjects, quickly building his reputation with photos of Yosemite and San Francisco. Carleton Watkins started photography in 1861 and became interested in landscapes, making photographs of California mining scenes and the Yosemite Valley. He favoured his mammoth camera, using large glass plate negatives, and a stereographic camera. He became famous for his series of photographs and historic stereoviews of Yosemite Valley, and his images helped influence the decision to establish the valley as a National Park in 1864.

Ansel Adams is known for his extensive photographs of nature, especially in the American West. His work continues to inspires potential and practising photographers throughout the world. Adams developed the Zone System as a way to determine proper exposure and adjust the tonal range of his final prints. The clarity and depth characterized his iconic black and white images of the American West. He used large-format cameras despite their size, weight, set-up time, and film cost, as their high resolution helped ensure sharpness in his images. HDR photography, shooting Raw or combining different exposures in layers may be considered to have similarities with Adams’ Zone System.

Landscape, impressionistic style.

Adams founded the Group f 64 (f 64 being a very small aperture setting that gives great depth of field on a large-format camera) along with fellow photographers Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham, to practise pure or straight photography over pictorialism. The group’s manifesto stated: ‘Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form.’ Adams also advocated the idea of visualization, where the final image is ‘seen’ in the mind’s eye before the photo is taken, to achieve the aesthetic, intellectual, spiritual, and mechanical effects desired. According to Adams, the natural landscape is not a fixed and solid sculpture but an image that is as transient as the light that defines it.

Weston was born in Chicago in 1886 and moved to California in 1907 when he was twenty-one, where he produced some of the most famous photographs taken of the trees and rocks at Point Lobos, near where he lived.

Photographers have always developed methods of improving and enhancing their images. In the early twentieth century Autochrome, an additive colour system, became available to produce colour transparencies. Ernst Hass achieved an impressionistic photograph of a landscape in the 1960s by double exposure: making the first exposure underexposed and out of focus and the second correctly exposed and in focus. Fay Godwin’s black and white images give us insight into the rugged and desolate nature of the landscape, featuring archaeological sites and ruins of stone structures while suggesting past inhabitance. Don McCullin’s moody black and white landscapes are littered with hints of human intervention: paths, fences, tracks and the English cultivated structural countryside. Martin Parr’s landscapes are characterized by the inclusion of people and enhanced colour, to suggest the social reality of an urban craving to escape to the less inhabited rural areas.

Today the countryside is reduced to a short tourist visit for a picnic or a holiday in England’s throw-away culture. The tendency of the photographer to ape the painter has passed. However it is still interesting and important to study the artists’ techniques, and a photographer can learn a lot from them. Interestingly, the top-selling paintings are still the traditional, local, modern and semi-abstract landscapes.

PHOTOJOURNALISM V ART

As with all forms of mass communication, from the development of the first telephones to the mobile telephones of today, from typewriters to word processing, even from the postal services to e-mail, the underlying motivation has been speed of communication. Within the photographic world, the developments in cameras and image processing were largely fuelled by the demands of the news industry, and the ability of that industry to recognize the need for fast information gathering and dissemination. Indeed, the success of a newspaper was, and still is, determined by the ability to publish a story (along with accompanying photographic images) quicker than its rivals, and our use of digital cameras and the digital darkroom today is directly linked to the developments within those industries. However, there is no doubt that the most important development in photojournalism was the commercial 35mm Leica camera in 1925, followed closely by the invention of flash bulbs. A golden age of photojournalism was born.

While content remains the most important element of photojournalism, the ability to extend deadlines with rapid gathering and editing of images brought significant changes. As recently as the 1990s, nearly thirty minutes were needed to scan and transmit a single colour photograph from a remote location to a news office for printing. Now, equipped with a digital camera, a mobile phone and a laptop computer, a photojournalist can send a high-quality image in minutes, even seconds after an event occurs. Camera phones and portable satellite links increasingly allow for the mobile transmission of images from almost any point on the earth. Along with this is the increasing use of bystander images to illustrate stories (inevitably this has not been welcomed by professional photojournalists or newspaper photographers).

Leitz logo.

Digital camera, mobile phone and laptop computer.

When photojournalism exploded onto the scene in the 1920s, Edward Weston was already an established photographer, and landscape photographer Ansel Adams was beginning his career. Both were enticed into photojournalism at different stages of their careers. Weston knew he wanted to be a photographer from an early age, and initially his work was typical of the soft-focus pictorialism that was popular at the time. Within a few years, however, he abandoned that style and went on to be one of the foremost champions of highly detailed photographic images.

Ansel Adams’ only known foray into photojournalism was the publication of a little known work, Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center, Inyo County, California in 1944. The book received mixed reviews. Some critics saw it as an important piece of photojournalism, while most condemned it as disloyal propaganda, to the extent that in some parts of the USA the book was publicly burned.

Image of lake and trees, using high dynamic range (HDR).

Adams and Weston’s decision to practise pure or straight photography over pictorialism was undoubtedly a reaction to the sensationalism that newspaper editors craved from their photographers. By the 1960s and 1970s, the newspaper readership also began to object to images that became more and more sensational and moralistic, reaching a pinnacle during the Vietnamese War. Many readers and politicians began to criticize editors who they felt were using editorials and photographs to dictate their own political views.

Ironically, therefore, while early photojournalism and pictorialism certainly seemed to attract more public interest between the 1930s and the late 1970s, the increasing sensationalism and politicization of the images saw the re-emergence of landscape photography as an art form.

DIGITAL V FILM

These days we can go out with one camera and shoot high quality stills and HD video. We can geotag our pictures so we know their exact location. No need to use your memory or a notebook. We can electronically copyright them in metadata and even shoot 3D. We, as photographers, are always looking for ‘the edge’, to produce new and exciting images. We can produce our own books and upload our photographs to the web, design the pages and add copy to them. Even if we have little or no design skills we can use pre-designed templates to help us and effectively self-publish them.

We can make albums on line, so a wider audience can view them, or we can limit who views them. Social networks are very powerful and they can be used to gain comment on our work from a worldwide audience. Photographic images can communicate far more than they ever could. Mobile phones have integrated cameras with higher resolution than the first professional DSLR. We now even have a huge range of applications (apps) that we can download to our phones to create artistic effects or tools that were once essential in our camera kit, such as exposure meters and remote control.

Where does photography go from here? There are certain groups of people who, in any social setting, would like to turn the clock back to those considered times when we had the time to think about what we would like to do and how best to do it. Traditional cameras and lenses that once plummeted in value have now found a new lease of life, older lenses being used on digital camera bodies or camera bodies being used as pinhole cameras, and thus taking photographers back to exposing film.

An older-style manual lens on a digital camera.

A selection of older manual lenses.

Wider aperture setting on an older lens.

Ironically we are now looking for a different way to portray the world and give it a different look. Put a cheap basic plastic lens on DSLR to give us that arty ‘less than perfect’ result. What about Polaroid? People loved those small instant prints, and Polaroid cameras are now selling for more than when they were new. Polaroid-type film is being made again to fit those cameras. Black and white photography has also found a new lease of life. It shows us something that we do not see in colour, as it can focus our minds on a particular subject or draw our attention to something that we may not have seen in colour. For the purist, the tonal range of film cannot be reproduced digitally.

Trees and snow in black and white, backlit.

For the landscape photographer our main asset is time. The digital revolution and the speed with which images could be shot and transmitted, whilst considered important for the media industries, is of less importance to the landscape photographer. We have time on our side. If a landscape photographer chooses to use a large-format plate camera, or a twin-lens reflex camera with film and wet processing, they can do so.

The potential to express ourselves using the medium of photography is now greater than we have ever had. Photography can be planned around quality of light, and the subject is chosen before the photography takes place. Photographers have the use of programs like Lightroom and Photomatix for HDR photography to produce the qualities in the landscapes that they are looking for.

The ideas and tools are ours – however, let us not forget that the viewer is the best judge of the success of the photograph.

“A photograph is not only an image, an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stencilled off the real.”

Susan Sontag, The Image World, 1982

Forest and rock – tonemapped – Vasterbotten, Sweden.

Chapter 1

Your Camera

If you have a desire to shoot and create interesting photographs then you are a good part of the way there. When you set out to take a photograph you should go by instinct and react to a scene; you should not need to worry about the right settings or lenses or whatever. Once you have the passion along with a camera you really enjoy using, and you know its menu system and have set it up to your liking, then it is all about using it as much as possible.

Knowing how to change your camera setting should be second nature to you. Modern digital cameras have different menus, and access to different camera functions through menus. When did you last read your instruction manual? Have you ever read it? Do you know your camera’s chip characteristics, what settings give you the best results for different situations? Do you know which of your lenses will give you the best result for a given situation? Do you know how well your lenses perform at a given aperture, how sharp they are at full aperture and when they are fully stopped down? Do you know your camera’s ISO performance limits and the way to get the best images you can from it?

You should strive for 100 per cent creative control, and free your mind to concentrate on creating the most imaginative photography you can achieve. You should be able to shoot without stress, without worry, without hassle.

WHICH CAMERA?

With so many brands and models to choose from, with so much information, how do you know what camera to buy?

To begin with, do you have a good idea of what you want to accomplish with your photography – personal satisfaction, relaxation, hobby or professional aspirations?

What style of photography do you want to concentrate on – landscape, macro, natural history, ecological, wild animals or birds, artistic or general nature?

What do you want the final product to be – a digital file that you show on a large screen, a digital file for publishing, a print or your own book of photographs?

If you have a camera in mind go and see if you can try it out first before you buy it. The camera may have the specifications you want, but are the economics right for you? Find out what cameras are available that will most closely match your budget and have the features and specifications you need. Narrow your search down, then arrange to try them out. Does the camera feel right?

Using a long lens and an aerial perspective draws the distant mountains closer.

Night mist on a lake.

DSLR v Compact

Why would you want a DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) when compact digital cameras are so much smaller, lighter and more affordable? The answer is versatility and image quality. Versatility, in that you can change lenses and add a wide range of accessories, from flashguns and remote controls, to the more specialized equipment that allows DSLRs to capture anything. It also about the creative versatility offered by the more advanced controls and higher-quality components. The quality difference between a good compact and a DSLR is minimal; both will produce sharp, colourful results with little effort. But when you start shooting in low light, capture fast-moving action or wildlife, or when you want to experiment, the advantage of a DSLR’s larger sensor and higher sensitivity starts to make a big difference. A DSLR cannot beat a compact camera for convenience, but for serious photography the DSLR wins hands down.

Types of DSLR

At the end of the day most cameras today will produce pictures that will be perfectly acceptable, but each brand has its own characteristics, and it is the one that you prefer using which is always the best.

Some are more suitable than others for particular photography. Generally the larger the chip size the higher the final quality. DSLR sensors fit into one of three sizes: Full Frame, APS-C and Four Thirds Sensor. The crop factor, as the sensor gets smaller, captures a smaller area of the scene. The result is a photograph that looks like it was taken at a longer focal length (1.5× or 1.6× longer for APS-C, 2× longer for Four Thirds).

Macro shot of flowers in a woodland setting.

If you are buying a DSLR to replace a film camera and you have got a kit bag full of lenses you need to be aware that unless you buy a Full Frame model all your lenses will produce very different results. For telephoto users the result is quite a bonus, as all your lenses will effectively get longer. But the wide-angle lenses will not produce a ‘wide’ field of view. So you may be forced to change some of your lenses to digital versions. APS-C is the most common format, used in Canon, Nikon, Pentax and Sony DLSR models. With a crop factor of 1.5× or 1.6× you need digital lenses to get true wide-angle results.

Four Thirds is a digital format developed by Olympus and used in Olympus and Panasonic DSLR models. Four Thirds is not based on any film SLR system and uses unique lens mounts, with the lenses in the system designed only for digital. Four Thirds offers compact camera bodies and lenses. But the smaller sensor means that they produce slightly noisier results in low light and at higher ISO sensitivities.

Full Frame DSLRs have the biggest, brightest viewfinders and because there is no crop factor they are often chosen by photographers who are upgrading from a film SLR and already own expensive wide-angle lenses. Also the larger sensor will produce the best results in very low light and at higher sensitivities. Full Frame cameras are usually larger and more expensive, but you will also lose the increased focal length offered by smaller sensor cameras when shooting with telephotos.

If you want longer lenses for more wildlife maybe you are better buying a smaller chip to give you longer lens capability or a camera that has a higher than average shooting rate to capture fast-moving subjects. You may want to work on macro subjects. If so you will need a camera that has the best range of macro lenses.

Special Considerations

If you intend to take photographs in low light or with long telephoto lenses, camera movement may be an issue. Image stabilization systems are designed to counteract the motion of camera shake. Each camera manufacturer has a different anti shake solution (such as SteadyShot, Vibration Reduction or OIS), but all are based on one of two different techniques: either by using a small element inside the lens or by the camera moving the sensor itself.

Even entry-level DSLR models focus and shoot faster than any compact. With the more expensive models the focus speed increases, and continuous shooting frame rate increases – important for sports and wildlife photographers. Entry level DSLRs offer a continuous shooting rate of about 2.5 or 3 frames per second but limit the number of shots you can take in a single burst.

If you need faster shooting you will need to move into the semi-professional range where you can expect at least 5 frames per second, although 10 and more frames per second are possible in some models. Together with a larger buffer memory this means that you can shoot more frames in a single burst.

If you are going to do a lot of photography in damp, humid or dusty conditions you will need a DSLR with some kind of weatherproof sealing and with a built-in dust removal system to keep the sensor clean.

If you like to travel light then perhaps one of the new generation of ultra compact lightweight DSLRs may be the answer.

Some DSLRs even have a rear screen that can be angled to offer a better view when getting behind the camera is difficult or when working at a low viewpoint.