28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The Language of Mixed-Media Sculpture is both a survey and a celebration of contemporary approaches to sculptures that are formed from more than one material. It profiles the discipline in all its expanded forms and recognizes sculpture in the twenty-first century not as something solid and static, but rather as a fluid interface in material, time and space. It gives insightful revelations of the creative journeys of ten renowned sculptors and showcases twenty-eight international sculptors. With over two hundred colour photographs, this sumptuously illustrated volume will inspire those intrigued by and interested in contemporary sculpture. Lavishly illustrated with 223 colour illustrations.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

THE LANGUAGE OF

Mixed-Media Sculpture

JAC SCOTT

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Jac Scott 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 722 9

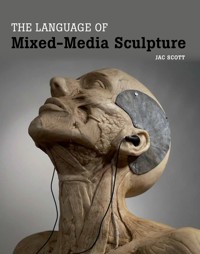

FRONTISPIECE: Bio Myopia, 2013, Jac Scott. Found road tar, discarded metal rod, glass test tube, seabird skull. 38 × 23 × 19 cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

DEDICATION

To Luke and Tom, my best creations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book has only been possible because of the immense generosity of the featured sculptors. I am particularly indebted to them for contributing inspirational imagery, personal logs and technical information that has made this book an insightful and informative study. Lastly, I appreciate that each had the faith in me to profile their work in a sensitive and sympathetic manner.

A thank you must also go to my husband, Michael Slaney, whose untiring support for my practice continues to sustain me.

CONTENTS

Preface

1. A DOOR AJAR

2. STRATEGIES FOR BEING

3. A SPACE FOR BECOMING

4. FLORA AND FAUNA LABORATORY

5. FOUND, SALVAGED, TRANSFORMED

6. DANCING WITH EPHEMERA

7. THE SOFT AND THE SENSUAL

8. THE SCULPTORS

Further information

Bibliography

Index

Difference is Important, 2012, Liz West. Installation BLANK SPACE Gallery, Manchester. Acrylic, mirror, objects, paint, coloured bulbs. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Liz West)

PREFACE

Since writing my last book about sculpture, Textile Perspectives in Mixed-Media Sculpture in 2003, my practice, like that of many artists, has significantly evolved. At that time, I was emerging from a world with an amorphous soft/hard dichotomy that steered my path resolutely towards sculpture, rather than remaining in what was, for me, the confines of the label of textile artist. As a member of the Royal British Society of Sculptors for many years now I revel in witnessing first hand the many talents and skills of a myriad of sculptors from across the world. It feels a good time to celebrate and what better way than to immerse myself in research about sculpture, finding new artists who excite me and then sharing this with kindred spirits – I hope you enjoy the adventure.

This book is not about teaching someone how to make art – I do not believe you can. Yes, it has some practical chapters, providing information regarding processes and techniques that you may find useful, but its main aim is to profile outstanding sculptors at the vanguard of the discipline, who may inspire others.

Atomic Equilibrium, 2013, Jac Scott. Old wooden picture frame, found discarded door lock, hand forged nail. 20 × 36 × 16cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

CHAPTER 1

A DOOR AJAR

If a painting is a movie running on a screen, a sculpture is a drama playing on a stage. Sculpture gives an audience and the artist more directions to evaluate. The audience can go inside a sculpture or come out of it to look at it. The artist’s message is a key for the audience to open their own door to experience the sculpture in 360 degrees. Sometimes, the audience will become part of a sculpture or participate in it. There is no limitation of the imagination of what a sculpture means to each individual audience. Sometimes, the imagination can pass through the timeline to see the elements from a different time or space.

Gong Yuebin in conversation with the author, 2013

The Language of Mixed-Media Sculpture is both a global survey and a celebration of contemporary approaches to the discipline in all its expanded forms. Sculpture in the twenty-first century does not just include something solid and static but rather a fluid interaction in time and space. Sculpture is sometimes used as a generic term for any 3D art, obviously this carries a large remit with it and it is not the scope of this book to try and define exactly what sculpture is – that would confine it unnecessarily. For the purposes of expediency, sculpture in this book will include object-making, works with ephemera such as light, air and sound, installation art and performance art where the fulcrum is an object. The material palette is unlimited – the essence here is that there must be more than one material used for it to qualify for consideration as mixed media. Expect to see the unexpected: gelatine and steel, charred trees and chains, soap and water, rat skins and silk-worm cocoons, cow dung and mirrors, sweets and wire, alum and light and many more combinations that tantalise and intrigue.

There is not the space to be all-inclusive, instead I have selected artists and their artworks from all over the world to act as a showcase to highlight the exciting developments taking place now in contemporary art. The Language of Mixed-Media Sculpture is intended as a toast to contemporary art that conveys the pulse and the spirit of mixed-media work created in three dimensions – it is not intended as a critique. The sculptors have all been selected to reflect a global perspective at the vanguard of today’s professional practitioners. Chosen for their innovative, and sometimes revolutionary, approach towards concept and materials, the book showcases some of their creative journeys, the practical processes they adopt and the dynamic final outcomes.

This book will not include the extensive history and influences behind the development of mixed-media sculpture – there are multiple readings of that already available. Instead its main aim is to focus on the richly conceptual practices of contemporary practitioners and how through sculpture they see the world. I have written this book from a sculptor’s viewpoint, not as a critic, nor curator, but instead from a perspective of comradeship and respect, to bring to the fore artists who have something worthwhile to expound. Many sculptors will be discussed but I have chosen twenty-eight exemplary artists to highlight – each has been generous and trusting in revealing their artistic practices to me.

There is no doctrine to press here and it should be recognised that many of the artists work across platforms and media and that this book is not intended to limit any of them by association. It is a celebration of three-dimensional art in all its glory and weird manifestations, to inspire, inform and enjoy.

Chapter 2, Strategies for Being, illuminates the artistic travelogue of nine selected sculptors. It is intended, through illustration, to reflect the many different journeys sculptors can take and how their influences are as diverse as their art. Strategies for Being does not present a biographical record of the sculptors, but instead there are selected extracts, written by the artists themselves, that reveal key facets of their creative make up, background and process.

A Space for Becoming focuses on the notion of the expansive body in sculpture. For over 60,000 years we have been moulding our likeness in a wide range of materials – creating narcissistic forms that aim to unravel the complexities of the human condition. The evolution of dismembering the body will be considered from Auguste Rodin to Ron Mueck – with Eliza Bennett, Andrea Hasler and Pascale Pollier providing insight into their practices. The employment of wax in depicting the realistic figure, and of alginate in casting body parts, will be discussed with useful guidelines included. Developed from this is the embracing of all material matter to mirror the figure in sculpture and the role of assemblage, and the influence of the Surrealists.

Full Fat or Semi-Skinned? (detail), 2004, Andrea Hasler. Installation Artrepco Gallery, Zürich, 2004. Metal hospital trolley, wax, resin, hydraulic tubing, baby bottle teats. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Raphael Hefti, courtesy of the artist and Artrepco Gallery)

Raised Threshold, 2008, Awst & Walther. Installation Hannah Barry Gallery, London. Gelatine, pigment, petroleum jelly. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Awst & Walther)

The chapter elucidates how the role of the body has changed from that of a subject for study to the actual canvas for artistic experimentation and performance. Placing the flesh, both internally and externally, at the hub of the sculpture are exponents Orlan, Mona Hatoum and Marc Quinn. The figure in a state of metamorphosis is briefly examined through the work of the Chapman brothers in the 1990s. The major dynamic of performance in the orchestration of multifaceted sculpture where the living body is pivotal is profiled through the practices of Noam Ben-Jacov, Awst & Walther, YaYa Chou (Taiwan) and Marilène Oliver (UK).

In Found, Salvaged, Transformed, the mandate that only materials from sculpture’s classical traditions are worthy is denounced, and in its place, the value of discarded and found objects in sculpture is discussed. Particular focus is on unusual materials, including: dust, figurines, cow dung, antique carpets, polystyrene and paper scraps with information regarding some ways to source and prepare objects. Techniques of using polymer plaster, of embedding objects in polyester resin and making papier-mâché to enable the debris to be transformed into memorable pieces are included.

Artist’s that proffer a new perspective on harnessing the old, the broken and the rejected in their work include: Catherine Bertola (UK), Liliana Porter (Argentina), Dorcas Casey (UK), Mark Houghton (UK), Andrew Burton (UK), David Chalmers Alesworth (UK) and Janet Curley Cannon (USA). The Flora and Fauna Laboratory chapter profiles the incorporation of organic materials, such as plants and animals, both living and dead, in sculpture. For some artists it is their way of connecting with nature and of making environmental commentary. This chapter examines the employment of: trees, plants, micro-organisms, insects and animals, with guidelines on how to preserve them. The featured artists have generously shared their ideas and methods – Andre Woodward’s (USA) love of using different types of trees in his work, Cath Keay’s (UK) interest in incorporating living insects and micro-organisms, while Kate MccGwire has a passion for feathers. Extraordinary sculptors, such as Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva (Macedonia) work with animal offal and fish skins and experimentalist Mary Giehl (USA) discusses her explorations of growing crystals.

Bull, 2011, Dorcas Casey. Clothes, stuffing, polymer clay, tape, rope, wire, and old furniture. 270 × 150 × 150cm. (Photo: Jasper Casey)

Site 2801, 2012, Gong Yuebin, Installation California State University, Sacramento, Clay, fibreglass, drapes. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Gong Yuebin)

On the technical side, an outline of taxidermy, using borax, cleaning bones, working with feathers, is included, plus using silica gel for drying and preserving fresh plants, and for treating materials to make them stronger, there is also guidance on coating with polyester resin.

The Soft and the Sensual chapter focuses on sculptors who harness materials that have an exceptional pulse towards the senses including: olfactory, tactile and taste – each a seduction incarnate. Gelatine is considered both conceptually and practically, through the work of partners Awst & Walther. The lure of textiles and the soft/hard dichotomy for exterior exhibition is explored through the practice of Dorcas Casey and her experiments with the product Jesmonite. The metaphorical underpinning of soap and sugar are key for Mary Giehl – guidelines on using both materials are provided. For YaYa Chou, the focus is the ingredients of cheap sweets in her Gummy Bear sweets assemblages.

Investigating transient phenomena, such as light, sound and air, is the primary aim of the Dancing with Ephemera chapter. As one of the most dynamic areas in current art practices, through the element’s amorphous attributes and thereby an ability to manipulate our sense of reality, the chapter will consider works that illustrate significance and potential. The key to inclusion is the employment of elements that are connected to another form of matter and therefore are mixed media. Light artist Peter Freeman (UK) is showcased with an impressive collection of works that not only transform environments but also metamorphose as they interact with the public through electronic devices. While Freeman masters the exterior, Liz West (UK) controls the interior with immersive saturated environments of pure hue and light. The role of sound is discussed with its invisible attributes that enrich and empower a seductive undertow in sculpture – explored through the work of Andre Woodward (USA), Catherine Bertola (UK) and Stelios Manganis (UK), among others. Air, the most nebulous of matter, is captured in the diaphanous work of Michael Shaw (UK).

In The Sculptors, the profiles of twenty-eight exciting contemporary artists from across the globe (along with my own work) are showcased to reveal the conceptual underpinning, and how this informs and guides our sculpture. It is intended as an inspirational insight into the breadth and current diversification in practice.

Finally, the book ends with a useful Research File with website information about the featured sculptors plus some addresses and suppliers’ details.