18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Covering almost 8 percent of the earth's terrain, lichens are living beings which are familiar to everyone, known to no one. They are one of those organisms that seem to offer nothing to hold our gaze. But the more time we spend with lichens, the more they reveal their beauty, their mysteries and their strange power of attraction. Part-algae and part-fungus, lichens call into question our customary ways of classifying forms of life, and allow us to conceive of an ecology that is no longer based on distinctions between nature and culture, urban and rural, competition and cooperation. The result of several years of investigation carried out on several different continents, this remarkable book offers an original, radical, and, like its subject matter, symbiotic reflection on this common but mostly invisible form of life, blending cultures and disciplines, drawing on biology, ecology, philosophy, literature, poetry, even graphic art. What if lichens were at the heart of some of the most pressing and topical questions of our day? Does the fact that they can live everywhere, even in very harsh environments, that they persist when almost all other traces of life have disappeared, mean that, despite their fragility, lichens are a force of resistance? After reading this book you will never see lichens, or the world, in the same way again.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 410

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

List of Illustrations

Part 1

Figure 1a Foliose Lichens Figure 1b Usneas

Figures 2a and 2b Diagrams of the symbiotic structure of three types of lichens, with the hyphae o...

Figure 3 Usnea growing on human skulls, from John Gerard, The Herball, or Generall histor...

Figure 4 © Pascale Gadon-González,

Signatures

, since 1998, series of photogra...

Figure 5 © Nathalie Ravier, “Glossaire des termes couramment utilisés en lich...

Figure 6a © Leo Battistelli,

Grayish Pink Skin

, 2010–2011, earthenware and pig...

Figure 6b © Leo Battistelli,

Sea Blue Lichen

, 2019, ceramic and steel, detail.

Chapter 2

Figure 7a (crustose; foliose; fruticose)

Figure 7b Fruticose (

Usnea florida

) and Complex (

Cladonia

)]

Figure 8 A pattern of lirellae of a lichen of the

Graphis

genus. © Vincent ...

Figure 9 Bernard Saby,

Untitled

, 1958, oil on canvas, originally in color, 130 x 9...

Figure 10a Ogata Kōrin,

Tai Gong Wang

, early 18th century, screen in two pane...

Figure 10b Collections of lichens in the herbaria of Geneva’s Conservatory and Botan...

Chapter 3

Figure 11a © Oscar Furbacken,

Degenerational Crown

, 2020, sculpture in polyst...

Figure 11b © Oscar Furbacken,

Beyond Breath

, 2012, series of cut-out photogra...

Figure 11c © Oscar Furbacken,

Micro-habitat of Rome 2 (Ageless Glow)

, 2020, i...

Chapter 4

Figure 12 © Nathalie Ravier, “Glossary of terms currently used in lichenolog...

Figure 13 © Pascale Gadon-González,

Biomorphose

(4991), 2019, gum bic...

Figure 14 © Pascale Gadon-González,

Biomorphose

(5110), 2019, with An...

Figure 15a © Pascale Gadon-González,

Paysage SP

, 2019, gum bichromate print, pa...

Figure 15b © Pascale Gadon-González,

Cellulaire

, 2018, with

Xanthoria

li...

Figure 16 © Pascale Gadon-González,

Conjonctions 1

, 2018, gum bichrom...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

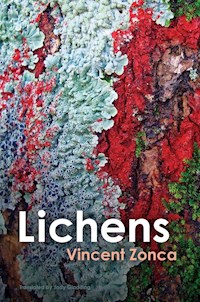

Lichens

Toward a Minimal Resistance

Vincent Zonca

Translated by Jody Gladding

Preface by Emanuele Coccia

polity

Copyright Page

Originally published in French as Lichens. Pour une résistance minimale. © Le Pommier/Humensis, 2021

This English edition © Polity Press, 2023

Excerpt from Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Die Furie des Verschwindens. Gedichte © SuhrkampVerlag Frankfurt am Main 1980. All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin.

Excerpt from Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Blindenschrift © Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 1964. All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin.

Excerpt from Saint-John Perse, Vents © Editions Gallimard 1946.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5344-0

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5345-7 (paperback)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022936786

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Illustrations

This table lists the black-and-white illustrations in the text, called “figures,” followed by their corresponding numbers. The color illustrations in the plate section are called “illustrations,” followed by their corresponding numbers.

Figures 5 and 12 come from an art project presented by Nathalie Ravier in 2014 at the School of Art and Design in Orleans. Figures 13–16 and illustrations 15 and 16 are microscopy photographs made in 2017 and 2018 by Pascale Gadon-González in collaboration with the scientific imagery platform of the Center for Applied Electronic Microscopy in Biology at the University of Toulouse III – Paul Sabatier (CMEAB).

Figures

1 Foliose and Usnea Lichens, plates in Johann Jacob Dillenius, Historia Muscorum, 1741.

2 Diagrams of the symbiotic structure of three types of lichens, with the hyphae of the fungi surrounding the cells of the algae.

3 Usnea growing on human skulls, from John Gerard, The Herball, or Generall historie of plantes, first published in London in 1597.

4 © Pascale Gadon-González, Signatures, since 1998, series of photograms, film print, variable dimensions.

5 © Nathalie Ravier, “Glossaire des termes couramment utilisés en lichénologie,” 2014, impressions on tracing paper, p. 47.

6a© Leo Battistelli, Grayish Pink Skin, 2010–2011, earthenware and pigment, 123.5 x 123.5 cm.

6b © Leo Battistelli, Sea Blue Lichen, 2019, ceramic and steel, detail.

7a Crustose, foliose, and fruticose lichens.

7b Fruticose (Usnea florida) and Complex (Cladonia).

8 A pattern of lirellae of a lichen of the Graphis genus (© Vincent Zonca, Rio de Janeiro, 2020).

9 Bernard Saby, Untitled, 1958, oil on canvas, originally in color, 130 x 97 cm (© Galerie Les Yeux Fertiles, Paris).

10a Ogata Kōrin, Tang Gong Wang, early 18th century, screen in two panels, originally in color, 166.6 x 180.2 cm (© National Museum of Kyoto, Japan).

10b Collections of lichens in the herberia of Geneva’s Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, 2018 (© Vincent Zonca).

11a © Oscar Furbacken, Degenerational Crown, 2020, sculpture in polystyrene, white concrete, iron, and fiberglass, originally in color, Norrtälje, Sweden.

11b © Oscar Furbacken, Beyond Breath, 2012, series of cut-out photographs (with the painting Rising in the background), originally in color, Katarina Church in Stockholm, Sweden.

11c © Oscar Furbacken, Micro-habitat of Rome 2 (Ageless Glow), 2020, inkjet print, originally in color, 52 x 80 cm.

12 © Nathalie Ravier, “Glossary of terms currently used in lichenology,” prints on tracing paper, p. 19 (2014).

13 © Pascale Gadon-González, Biomorphose (4991), 2019, gum bichromate print, with Xanthoria lichen, Rome, Italy, 30 x 40 cm.

14 © Pascale Gadon-González, Biomorphose (5110), 2019, with Anaptychia lichen, originally in color, Rome, Italy, pigment print, 30 x 40 cm.

15a © Pascale Gadon-González, Paysage SP, 2019, gum bichromate print, palladium plate, or pigment print, 100 x 160 cm.

15b © Pascale Gadon-González, Cellulaire, 2018, with Xanthoria lichen, gum bichromate print, 38 x 28 cm.

16 © Pascale Gadon-González, Conjonctions 1, 2018, gum bichromate print, 38 x 28 cm.

Plate Section

1 Anton Elfinger, medical illustration (lithograph) of Lichen ruber pilaris, in Ferdinand Hebra, Atlas der Hautkrankheiten [Atlas of Skin Diseases], published by the Imperial Academy of Sciences (Vienna: Braumüller, 1856–1876) (© F. Marin, P. Simon / Bibliothèque Henri Feulard, Hôpital Saint-Louis AP-HP, Paris).

2Herpothallon rubrocintum lichen, Brazil, Botanical Garden of São Paulo, 2018 (© Vincent Zonca).

3 Crustoce and foliose lichens growing indiscriminately on the trunks of bamboos and a plastic chair, Brazil, Ubatuba, 2020 (© Vincent Zonca).

4 Graphidaceae lichen of the Phaeographina genus, Colombian Amazon, Ticuan region, Rio Amacayacu, 2018 (© Vincent Zonca).

5 Antoni Pixtot, Saint George, 1976, oil on canvas, 194.5 x 97 cm. (© Dalí Theatre-Museum/ © Antoni Pixtot 2022).

6 Foliose lichens grow by rising through, by “licking,” the surface of their support: here, a Xanthoria parietina on a deciduous tree branch, France, Burgundy, 2019 (© Vincent Zonca).

7 Chen Hongshou, Plum tree in blossom, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 124.3 x 49.6 cm. (© National Palace Museum, Taipei).

8 Leo Battistelli, Globe Lichen, detail, ceramic, 2020, exhibition at the Casa Roberto Marinho in Rio de Janiero, 2020 (© Fernanda Lins).

9Leo Battistelli, Red Lichen 1, 2019, ceramic, steel, and acrylic, exhibition at the Casa Roberto Marinho in Rio de Janiero, 2020 (© Fernanda Lins).

10 © Oscar Furbacken, Micro-habitat of Stockholm 1, 2020, photographic print, 70 x 105 cm.

11 © Oscar Furbacken, Urban Lichen, 2009, Sweden, Stockholm, Swedish Royal Academy of Beaux-Arts, photographic print on painted paper, 500 x 560 cm.

12 Luiz Zerbini, Mamanguã Reef, acrylic on canvas, 293 x 417 cm. (© Eduardo Ortega).

13 Yves Chaudouët, Lichens 1, lithograph, Atelier Clot, 1998 (© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022).

14 © Pascale Gadon-González, Cellulaires Contacts 5, 2017, with Evernia prunastri (7296), lichen collected at La Vergne in Charente, 2017–2018, pigment print, 30 x 30 cm.

15 © Pascale Gadon-González, Bio-indicateur Usnea, 1999, lichen collected in Corrèze à Maymac, lambda print mounted on Dibond, 120 x 80 cm.

16 © Pascale Gadon-González, Bio-indicateur Cladonia coccifera, 1998, lichen collected in Ariège, lambda print mounted on Dibond, 120 x 80 cm.

Acknowledgments

This inquiry, which mixes very different domains, has led to many lucky and generous encounters. I would like to thank all those with whom I’ve been able to discuss this subject; the book is the result of these exchanges, and those human interactions, invaluable to me.

My thanks, especially, to Elise Heslinga and the whole team of Polity Press, to Jody Gladding who has given hospitality to these Lichens in the English language, to Emanuele Coccia, as well as to the scientists and artists who have been so kind in opening their studios, their laboratories, and their collections to me, although the lines between these places often blur: Philippe Clerc and the Conservatory and Botanical Gardens of Geneva (Switzerland), Teuvo Ahti and Saara Velmala of the Botanical Museum of the University of Helsinki (Finland), Tomoyuki Katagiri of the Hattori Laboratory of Nichinan and Yoshihito Ohmura of the National Museum of Nature and Science of Tokyo (Japan), Jean Vallade (in Dijon), l’Association Française de Lichénologie, Trevor Goward (in Edgewood, Canada), Adriano Spielmann (in Brazil); Pascale Gadon-González, Yves Chaudouët, Oscar Furbacken, Luiz Zerbini, Leo Battistelli, Nuno Júdice, Olvido García Valdés, Jaime Siles, Claire Second, and Marie Lusson. Deep thanks as well to Nicolas Cerveaux, Ambroise Fontanet, Marjorie Gracieuse, Doriane Bier, Hector Ruiz, Jérôme Bastick, Maxime Chapuis, Ricardo Marques, Patrick Quillier, Mitsuhiro Kishimoto, Chantal Van Haluwyn, Éléa Asselineau, Guillaume Milet, Pierre-Yves Gallard, Emilio Sciarrino, Inès Salas, Makiko Andro, Henry Gil, Clémence Jeannin, Johan Puigdengolas, Miguel Arjona and, above all, to Thérèse Zonca-Philippe, Gabrielle and Camille Philippe.

PrefaceBeyond Species

From the beginning, life has seemed to us to be divided into incompatible forms: the dandelion (Taraxacum ruderalia) has nothing in common with the squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris); the butterfly (Morpho menelaus didius) can’t be compared to a cork oak (Quercus robur). Life immediately appears multiple, dispersed into incompatible and irreconcilable forms. The diversity of species and forms is both obvious and threatening: no sooner is it established than it seems to show both diachronic instability (evolution) and synchronic instability (the struggle between species and competition, ecological disasters).

Yet this multiplicity that divides life in a formal and ontological way is not all that obvious after all. The division of life is always problematic. Plato was the first to understand this, as in one of his best-known myths. In Protagoras (320d–322c), he tells how the immortal gods wanted to create forms of mortal life and charged two giants, Prometheus and Epimetheus (literally: the one who thinks of things first and the one who thinks of them later) with the task of granting each species appropriate powers. Epimetheus asked to be allowed to do the distributing, giving some creatures “strength without speed,” and others speed with less strength; some were armed with weapons, while others were able to hide, being small, or to protect themselves because of their large size. In the distribution of attributes, Epimetheus sought balance and made extinction impossible for any species. He gave them fur to withstand the cold, hoofs, and tough skin. He appointed different sorts of foods for different species, and arranged an order by which one could eat another, establishing procreative rates accordingly. But he had forgotten one species, humankind: “All the animal species were well off for everything, but man was naked, unshod, and defenseless.” So Prometheus stole from Hephaestus and Athena their technical skill, as well as fire (which allowed for the use of this skill), and he gave these to man.

Plato adds three notes to this myth. First, the wisdom of Athena and Hephaestus did not include politics. It was Zeus who later gave this knowledge to men, with Hermes as intermediary, and it was only then that humans were able to make war with other species, “because the art of war is part of the art of politics.” The gift of technical skill also established human kinship with the gods. That’s why only the human species makes altars and images of the deities. And finally, thanks to this skill, humanity was able to “discover articulate speech and names, and invent houses and clothes and shoes and bedding and get food from the earth.” Language is only a consequence of this wisdom and not its foundation. In other words, technical skill precedes reason and is its basis, the condition of the possibility.

The first point to emphasize in this myth is that the war among the species originates in an unjust division. Or rather, what we call biodiversity, the plurality of species, is itself a form of injustice. It is a matter of a division carried out by an imprudent and incapable deity (Epimetheus) who unequally distributes the characteristic powers of each species. Already there is something extremely radical in this act: species are not characterized according to what they are but according to what they have; any identity is not inherent nature but arbitrary gift. The division of the species is intrinsically arbitrary, resulting from a political form of distribution of what, by nature, belongs to no one. In addition, this division produces a sort of non-species, a sort of proletariat of living beings. For all species, identity is defined by the possession of powers. But humanity, on the contrary, is without possessions, without powers. It is this resentment that defines the war. On the other hand, this resentment prompts a sort of Bovaryism: the desire to be like other species.

Faced with the injustice caused by one god, the myth continues, another god tries to compensate. But his solution produces another, double, injustice: the non-species, the most proletarian of species, receives through theft a quality that belongs only to the divine – the possessors of qualities that other species received in usufruct. This additional gift – skill and fire, considered together as the power that allows materials and reality to be manipulated – permits humanity to establish itself in a relationship of hierarchical superiority. The act that was supposed to correct the inherent injustice in the division of powers produces another, even more radical, injustice.

Plato’s myth describes the multiplicity of species as inherently arbitrary: a distribution carried out by a minor god, following criteria not the least bit rational, and with a kind of thoughtlessness or disregard (one of the possible translations for the name Epimetheus). But, precisely because it is arbitrary and profoundly unjust, and is then followed by a second injustice – which religion and then politics sanction – this division calls for its own suspension. What is called into question is not so much, or at least not only, human nature, but rather the nature of all species. In opposition to the acquiescence that biology, politics, various theologies, but also and especially ecology has shown in the face of the supposed obviousness of the ontological separation of all species, we must offer less conciliatory discourse. The existence of species is not an ontological fact, it’s a practical one. That’s why the question of taxonomy – the order that separates one species from another, that defines the reciprocal positions of different living species within the tree, or rather the network, of life – as it’s appropriate to speak of it now, following the discovery of horizontal genetic transfer, must become a purely political and no longer a genealogical question.

From this perspective, lichens are players in a new politics of the living: as opposed to the ontological subdivisions of life, they define identity through association, not division. They struggle – throughout their lives – to overcome the division of species. The life that traverses all is always one and the same. That is the only way it becomes possible to commune with beings so far removed in terms of taxonomy and genealogy.

It is this kind of biological communism that Vincent Zonca’s book affirms by locating lichens – “living beings situated on the margins, in resistance” – at the very core of the thinking about a new biology. These beings, often described as “leprous,” “pustular,” “tubercled,” which are neither plants nor animals, nor singular, require us to rethink the rules regarding the distribution of identities. They also require us to consider any species as a contingency, which the existence of any individual being – and the encounters to which it gives rise – is destined to go beyond. Life belongs to all the species, and the powers that define each of them must be held in common.

Emanuele Coccia

Quote

“Like a runaway horse, [the mind] takes a hundred times more trouble for itself […] and gives birth to so many chimeras and fantastic monsters, one after another […]”

Michel de Montaigne, “On Idleness,” Essays (1571)

“In our moments of confusion

often I feel the need

to contemplate a lichen.

Bring me a mountain

and I’ll show you what I mean.”

Hans Magnus Enzensberger, “Braille” (1964)

Part 1FIRST CONTACTS

“The botanist’s magnifying glass is youth recaptured.”

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 1957

Origins

From the very beginning there was this fascination for strange, unusual words with mysterious meanings and barbaric sounds. Lichen. But also: tundra, wrack, cercus, elytron, dolmen, maelstrom, inlandsis, fjord, permafrost, ubac, adret, axolotl, cortex, pollen. An abecedary of nature, its music marked by the etymology of origins: Greek, Latin, or borrowed from other languages. Those words that, as soon as they are pronounced, create a kind of air current, a moment of suspension. Silex, granite, mitochondria, sphagnum, vraic: lichen. The hardness of the central “ch,” the strangeness of the final “en.”

*

Victor Hugo is one of the rare francophone poets to have dared elevate lichen to the rank of verse. He rhymed it with a fabled monster of Norwegian origin: the “kraken.”1

*

It was also a kind of fascination with what is neglected, rejected, denigrated. Adolescence of the accursed poet and lichen, of wild grasses and garden sheds, wandering in search of what lay forgotten off the beaten paths, far from what everyone could see, in search of a territory, a “no man’s land.” Arborescence of the accursed poet who was trying to construct himself by cutting through fields, gleaning, endlessly branching into a sinuous and ever uncertain verticality.

I made lists of everything, lists of word scraps, backbones for supporting an encyclopedic and solitary imagination as I sought refuge in difference, rarity, the unknown. I investigated the most mysterious pharaohs and dinosaurs. I examined the most repulsive insects, the grubbiest worms; I dissected the blisters on trees in search of inner parasites.

Lichen belonged to the imaginary world of my childhood and adolescence. It inhabited the north faces of the deep forests of my native Burgundy and my lonely dreams. It became conspicuous during those winters that lasted forever, swallowing autumn and stretching into spring, when it was the last visible sign on the bark of the Austrian black pines, in a melancholy landscape of gray and fog, the trees displaying only “their agony of strings,” no more leaves or colors – skeletal calligraphy reduced to the elemental.

Winters

If there is a season particularly favorable to lichens, it is truly winter. “Supple physiology allows lichen to shine with life when most other creatures are locked down for winter,” writes David George Haskell.2 While many trees lose their leaves and most of the higher forms of plants disappear, they burst forth in all their colors and extravagant forms. Lichens are the “leaves of winter,” wrote Henry David Thoreau. A few pixels forgotten on a canvas.

This is the season that inspired the magnificent descriptions of lichens in Thoreau’s Journal from the mid-nineteenth century and the northeastern US woodlands – or those of Marcel Proust, Francis Ponge, the haiku poets of Japan. For botanists, this is the fallback – or vexing – solution, for lack of anything better when there’s nothing left to study. To the aptly named Malesherbes, Rousseau claimed that “winter has […] its collections of plants that are specific to it, for learning the mosses and lichens.” It is also the season when, during the botanical walks that they so loved, the artists George Sand and John Cage, in the respective company of the botanists Jules Néraud and Guy Nearing, temporarily abandoned plants and mushrooms to let lichens take them by surprise.

*

I stared at those balls of disheveled usnea found on a cherry tree in the family garden. They resembled nothing identifiable, lumps of grass or pale mops of hair so dried out they seemed almost mineral. What were they saying to me?

Lichen is what persists when almost all trace of life has disappeared, in the eternal winter of the poles and the high mountains as well. They become visible, appear, in adversity. Lichen: a critical force?

Weeds

Lichen is familiar to everyone, known to no one. You need only ask those around you: everyone sees, more or less, what the word designates; everyone has already set eyes on those aberrant patches on walls, those strange growths on tree bark. It falls into the order of the “infra-ordinary” to adopt Georges Perec’s term; it is “what happens every day and what reappears every day, the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the background noise, the habitual.”3 But no one has lingered over it or is capable of saying anymore about it: language stops there.

In botanical gardens and parks, no signs ever point out lichens or explain them. A laughable, useless presence on walls, tree trunks, and rocks, even downright repulsive, calling up in the imagination a stain, a kind of eczema or leprosy, pruritus, the idea of an unhealthy, oozing excretion, a disheveled parasite sucking the lifeblood from its host. In 1743, the Chinese poet Qianlong wrote:

This ravenous parasite which, disdaining the earth whose sap it rejects, will go seeking above it a more abundant and better prepared food: countless filaments, which we might mistake for so many strands of gold, bind it indissolubly to the plants that it devours.4

At best it is confused with moss or tree bark in the forests, in cities, with guano on the walls or rubbery debris on our sidewalks.5 It seems not to have its own identity or to be reduced to a matter of “secretion”: it is what comes out, what the body rejects, what nature produces that degenerates and proliferates if we are not careful. Something neglected, a deviance.

In this period I was somehow absent from my body, refusing to support it in any way, to the point of letting this beard grow, like mold, like lichen, which would prove each day to be less and less my style.

Jean Rolin6

For the ancient Greek scholar Theophrastus, lichen grew from bark. For others, it is “cliff snot” (the Canadian poet Ken Babstock) or “excrement from earth” (oussek-el-trab or ousseh-el-ard in Arabic, most likely naming the lichen Leconora esculenta with its suggestive brown curves). In natural history, (de)classified first among plants labeled “inferior,” it was long treated with disdain and discredited. For Albert the Great, Dominican friar and thirteenth-century philosopher, lichen, located at the bottom of the “vegetable” hierarchy, was the product of putrefaction.

Few bother to worry about the loss of this invisible companion. Because of its size and appearance, it does not have the same charisma as seals, tigers, or orchids. It is part of what, for decades, the scientific community has called “neglected biodiversity.” This expression was coined and democratized following marine and terrestrial expeditions by the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris.7 It points to the fact that a large part of the natural world, which is least well known to the general population, of least interest to the media, and often least studied by the scientific community, is also the part richest in still undiscovered species. It is estimated to represent no less than eighty percent of living species: insects, planktons, mushrooms, lichens, and so on.

In 2016, Emanuele Coccia rebelled against a veritable “metaphysical snobbery,” by which the living world and plants in particular had been forgotten by philosophy (at least recently) and condemned to “vegetate.”8 It is possible to be interested in ornamental plants (because of the wholly relative power of beauty) and those considered “useful” (the ones that have nutritional or medicinal “properties”). One might also notice those labeled “superior,” higher, to better distinguish them from “inferior” plants, lacking flowers, without lures, subterranean, and lowest on the scale of values: “weeds” and “wild grasses.” Hence the dubious honorary chair granted to Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in 1790, as a snub at the end of that great naturalist’s unappreciated career, when he was named the Jardin du Roi’s Professor of Natural History of Insects and Worms.

Faceless, mineral and inert in appearance, lichen poses a moral and political problem: it inspires no spontaneous empathy. Like other “lower” beings, it has a hard time accommodating anthropomorphism. Unsurprisingly, scientific studies show that the species for which we feel the most empathy are those closest to us from an evolutionary perspective – and with regard to their appearance.9 For Emmanuel Levinas, it is through the face and body of the other – “otherwise than being” – that a sense of ethics develops, that it’s possible for us to take measure of our humanity.10 Lichens, insects, planktons: so many organisms that offer nothing to hold our gaze, no spontaneous reflection; so many living beings that we can’t “look in the face” to question ourselves (even though the naturalist lexicon for describing them, as is so often the case, relies on metaphors drawn from the human body; see below, p. 10). Sylvain Tesson writes:

To love is to recognize the value of what one will never be able to know. And not to celebrate one’s own reflection in the face of a similar being. To love a Papuan, a child, or a neighbor – nothing could be easier. But a sponge! Lichen! One of those little plants roughed up by the wind! That is truly difficult.11

A sense of ethics based on anthropomorphic identification can be a start but cannot be the only vantage point from which to act. And the very species least known to us count among those most in danger. This problem of identification is a real challenge on the level of political action. How to engender an active awareness of the environment without easy recourse to empathy, without the emotional appeal of an imploring look or a heartbreaking cry? How to learn from this quiet, immobile life? Neglected biodiversity: poorly known and about to disappear? Must lichen be condemned to the scholarship of specialists or to our idealization of the marginal and compassion for antiheroes?

*

In Europe and in France, where I’m from and which is the point of departure for my obsession and my intended inquiry, how to explain this paradox of the familiarity and invisibility of lichen? It has no common function or market value. We do not eat it, use it, or sell it; thus we do not see it. An almost total eclipse, except in the eyes of a few initiates. The only books I’ve found that discuss it are specialized botanical manuals. Until the early twentieth century, these were written in Latin – carrying that distinction of language, knowledge, and power.

Lichenology has never descended to the level of the lay person for the simple reason that lichens are not, in our country, of any use, at least since medicine abandoned the doctrine of signatures.12

Democratic by its very nature – present and visible almost everywhere, even in cities – it is, at the same time, unpopular.

Someone who takes an interest in lichen, who takes the time and trouble to stop in front of a wall, to circle a tree trunk, to climb a roof, and to approach it close up, is thus seen as eccentric, enlightened, unnerving. Imagine: a passerby who stops in the middle of Paris to examine a vague spot, yellowish and scaly, on the far side of a plane tree! Or who suddenly starts scraping the stones of a historic monument – while the tourists have stepped back far enough to admire it or to take selfies with it! A lichenologist can spend an entire day with the same rock. This is the experience of alienation that the novelist and lichenologist Pierre Gascar recounts in the 1970s, while gathering lichen in the Jura countryside:

What, this scab, these kinds of aborted mushrooms? And probably poisonous to boot. No creature in the world dares touch it, and haven’t you noticed how it makes the trees it grows on wither? Now the vague suspicion that my prowling ways seemed to have planted in these villagers’ minds became clear. I would be accused of black magic.13

*

Lichen has long been considered a repulsive, parasitic, morbid organism, “the pallid gray of old stone,” as Émile Zola wrote, unworthy of interest unless it had some use for industry or survival. For evidence, we can cite the long history of its definition and its classification, as well as the original double meaning of its name, which associates it with a skin disease.

Let us take a glance at Shakespeare:

ADRIANA […] Come, I will fasten on this sleeve of thine:/ Thou art an elm, my husband, I a vine,/ Whose weakness married to thy stronger state/ Makes me with thy strength to communicate./ If aught possess thee from me, it is dross,/ Usurping ivy, brier, or idle moss [“bearded lichen,” “usnea”];/ Who all for want of pruning, with intrusion/ Infect thy sap and live on thy confusion.14

TAMORA Have I not reason, think you, to look pale?/ These two have ticed me hither to this place,/ A barren detested vale you see it is;/ The trees, though summer, yet forlorn and lean,/ Overcome with moss and baleful mistletoe./ Here never shines the sun; here nothing breeds, […]15

In these two scenes, lichen is evoked in a negative way to describe characters or their surroundings. It is viewed as a parasite that maliciously kills the tree on which it lives.

From the beginning (and this is still the case today), in ancient Greek, the word “lichen” (leikèn) designated by visual analogy both the organism (or the organisms resembling it) and dartre, a skin disease, “feu volage” [“fickle fire”] as it was once called in French, that leaves colored lesions and dry, scaly patches (see Ill. 1):

We gradually see the dermis become infiltrated by embryonic elements, thicken, and turn hard and rough; the papillae hypertrophy and sometimes even group in a way that simulates quite irregular and uneven papules. […] Soon the skin presents a very singular aspect, characterized by the exaggeration of its natural folds, forming a sort of checkered pattern of more or less wide and regular weave. […] This is the morbid process to which I give the name lichenification.16

The image described here by Doctor Louis Brocq is striking. It evokes the thallus of the lichen – that is, its exterior tissue that includes no leaf, stem, or root, and which is the form we see with the naked eye. We find this “vegetalized” image of the body again in another disease, canker, called “the tree disease.”

Portraits by naturalist writers have always struck me with their power and richness. Joris-Karl Huysmans and Zola cannot resist playing with the double meaning of “lichen” to describe the physical and moral decadence of their characters by “vegetalizing” them, by reifying them. These lines are particularly memorable:

The monk entered.

He was the most senior member of the monastery, even older than the Father Priest, because he was over eighty-two years old. Thus, as on the forgotten stump of a very old tree, lentils, lichens, and burrs were growing on his head.17

There was no end to the train of abominations, it appeared to grow longer and longer. No order was observed, ailments of all kinds were jumbled together; it seemed like the clearing of some inferno where monstrous maladies, the rare and awful cases which provoke a shudder, had been gathered together. […] Well nigh vanished diseases reappeared; one old woman was affected with leprosy, another was covered with impetiginous lichen like a tree which has rotted in the shade.18

Conversely, scientific descriptions of lichens have continually used nosographic metaphors to characterize different genera. Lichen is very frequently called “leprous” (there is one family of Lepraria – the Latin word lepra was used by ancient Christian writers to designate sin and heresy, which attacked and damaged objects), or “pustular,” “tubercled.”

Patch of eczema,

an itch the rock can’t scratch

though the wind’s scouring pad

of grit and sleet brings some relief.

from “Lichen” by Lorna Crozier19

Two motives for these metaphors: crustose and foliose species of lichens seem like so many dermatological manifestations on a surface (see Ill. 2) – the bark of a tree, the outer layer of a wall – while the thalli of fruticose species resemble bristles or shaggy hairs on their supports (see Ill. 15). Thus Usnea barbata or bearded usnea is also called barba de viejo, Saint Anthony’s beard, Jupiter’s beard, barba or bigote de las piedras (in Argentina and Chile), old woman’s hair tuft (in Arabic). In Finnish mythology, Tapio, god of the forest, is represented with a beard of lichen and moss eyebrows. Victor Hugo describes lichen as “fur” on trees or a “hairdo” on ruins. If you leaf through botanical manuals, such personifications appear everywhere. From the Latin names and the descriptions a whole imaginary world of skin and hair emerges. Lichen is said to be “wrinkled,” “scale-like” (“squamous”), “flesh-colored,” “full of warts” (Icmadophilia ericetorum), “veined,” “nippled,” as well as “hairy,” “bearded,” “long-haired,” “frizzy,” or even “bristly” (Phaeophyscia hirsuta), resembling horse hair, “surrounded by hairs,” or “ciliated,” growing in the “armpits of branches” (Cladonia uncialis), or “blackish and hanging like the tail of a horse” (Usnea jubata), and so on.20 For Huysmans, the image becomes fantastic:

Here the tree appears to him as a living being, standing upside down, its head buried in the hair of its roots, raising its legs in the air. […] In the joints of the branches, other visions reside, elbows and armpits covered in grey lichen; the very trunk of the tree is scored with incisions which spread out like enormous lips beneath rust-coloured clumps of moss.21

Used in the West since antiquity for dyes and medicines, lichen would not be identified in the language or clearly distinguished from other realms until the nineteenth century, the period in which it truly began to make its appearance in scientific discourse and the arts.

*

Eclipse – or explosion? The more closely I approach lichen, the more I see it. Everywhere. In the streets, on the trees, all about us, but also among my contemporaries. When I search through poetry collections from around the world, I discover, turning the pages, first one lichen, then another. I uncover it in the titles of literary reviews (see below, p. 135), among painters, printmakers, photographers, sculptors, before finding it featured prominently in current scientific articles. A simple coincidence? No hermeneutic circle, Proustian madeleine, or adolescent romanticism, but rather a burgeoning, a repeating refrain, a revelation. Lichen, and its proliferation, its politics. What does it want to tell us?

As the object of renewed interest, even rehabilitation, could lichen have particular relevance for today’s societies, could this be lichen’s “moment”? What is hiding there? What does it hide? This book thus has a dual subject. What does it say about us, about our relationship to nonhuman nature, this little organism flattened against walls? But also, how does lichen come to appear today as a catalyst for our images and fantasies, as a necessity for thinking about the twenty-first century and weaving new relationships?

Beginning from this postulate, I decided to conduct an inquiry, without really knowing where it would lead me, what it would tell me. Over the course of many years, it would have me traveling from France and Switzerland, where I began my research, through the old collections of libraries and herbaria, on to Finland, Sweden, Brazil, and Japan, countries rich with lichen. But to complete my investigation, I had to invent yet another type of travel, a methodology that involved working across the fields of science. This means of access, furthered by the anthropological approach, falls into the line of “diagonal” or “oblique” sciences advocated by Roger Caillois in 1959. It also draws from the methodology of so-called “comparative” literature that brings various contexts and fields of knowledge into dialogue. Even more radically than the philosophy of science, ecocriticism, or anthropology, it involves mixing biology, literary and art criticism, ethnology, and philosophy all together at the same time in order to cultivate curiosity. This is the chosen stance of the undisciplined approach of the essay, the symbiotic functioning of lichen: joyously to blend the disciplines and extract the juices. The cross-disciplinary approach of living beings, and especially of plant life (fungi), even more relevant than “ethnobotanical” science, originated in the nineteenth century and has enjoyed growing success in the last few years. And so, to welcome a diversity of voices, this essay will grant much space to quotations.

The moment has come to give lichen a chance, to give it the right to literary existence by making it the subject of reflection, by studying its democratic – and popular – power.

A Scientific Challenge: Remaining or Rising in the Ranks

At the end of 2017, in order to investigate the strange world of lichens and their relationships with human beings, after long searches on the Internet, I decided to explore Geneva’s Conservatory and Botanical Gardens on the shore of Lake Geneva. Located in what is now the neighborhood of large international organizations (UNO, OMC), the dark, orange-colored façade of the Conservatory rose before me like a temple consecrated to botany, but also like a place cut off from the world. On either side of the entrance, busts of great Swiss botanists face the intimidated visitor preparing to knock at the monumental door. Philippe Clerc ushered me in. He welcomed me with enthusiasm and kindness; his eyes sparkled as soon as I began to “speak lichen.” He could talk forever about his lichenology research – as well as about the species he was currently exploring: the small “yellow heart usnea (Usnea wirthii).” He began by leading me down to the basement where he showed me the incredible Genevan herbaria that fill almost eighteen kilometers of shelves (see below, Figures 10a and 10b). Each species has been referenced and carefully wrapped for centuries in old newsprint and folded paper. Many lichens are represented there. Cracking open an envelope reveals a specimen: dried lichen from every corner of the globe, mounted on stone or in fragments, accompanied by its Latin name, neatly handwritten. There are also mysterious red envelopes that contain the “types,” the three to five percent of samples used throughout the world as references, a kind of standard for the description of each species. Philippe Clerc then led me to the library, one of the most extensive collections in the world on the subject of mushrooms, mosses, and lichens (that group with the enigmatic name of “cryptogams” – “organisms whose nuptials are secret”). Before me stretched shelves of botanical books, in Latin and other languages, including Russian and Japanese, very old editions with magnificent illustrative plates. But I found very few pages on ethnobotany, the anthropology of lichen, its images and discourse.22 One needed to know how to read between the lines, to understand the conventions, to learn to decode the scientific jargon, to see how the supposedly objective descriptions betrayed in one way or another the state of the sciences, a way of thinking and seeing, a culture.

*

What exactly, outside of the medical sense (lichen-dartre), what is “lichen” for a botanist?

A living being, a trace, an originary bond. It is that small and strange organism, strange because double: a fungus that is joined to an alga, there where everything begins. The novelist Pierre Gascar writes:

A structure that is basically branched, a fleshy, non-vascular tissue that has the silkiness of scars: lichen retain something of the fetal. Nevertheless there is no plant more perfectly realized, or presenting a more complex form of organization.23

Formerly categorized with plants, lichens left their first marks in the work of the Greek philosopher and botanist Theophrastus (371–287 bce), where we also find the first botanical use of the word. There it refers especially to the liverworts or hepatics, plants that grow notably on the trunks of olive trees and resemble mosses and lichens because of their thalli and the fact that they fasten onto trees and stones.

The word “lichen” in the botanical sense appeared in French in the sixteenth century, in particular in the botanical writings of Rabelais where, as in the ancient Greek, it refers to the lichen used to treat dermatological lichen. But it could also designate species of mosses. For many centuries, lichen was assigned to the family of mosses, or even of algae (by Carl Linnaeus), then to a fuzzy middle ground between algae and fungi. In that period it continued to be considered a secretion from the soil, trees, and rocks. About 125 species were identified. Beginning in 1694 with the great French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708), and especially in his Institutiones Rei Herbariae, “lichen” – the organism but also the Greek word – became its own botanical category, distinct, finally, from mosses and hepatics. It was part of the “apetalous flowerless” group. We still have yet to define it by what it has (or what it is) rather than by what it does not have (or what it is not).

Some forty years later, in 1741, the English botanist of German origin, Johann Jacob Dillenius (1684–1747), associated with the taxonomic revolution carried out by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, made the first distinctions within this group (although he continued to link them with mosses), beginning with the form of the thallus. In his Historia Muscorum (1741), he tried to list all the “inferior plants” (661 species of mosses, algae, hepatics, and lichens) that he knew, with more than eighty magnificent plates that he engraved by hand. Because botanists are very often artists who have learned the art of drawing (and more recently, of photography), when they cannot collect a plant, or in order to note all its details, they draw it. Despite its commercial failure, this book was an astonishing foundational landmark in the history of botanical sciences. The taxonomy of lichens was then significantly expanded and deepened by a student of Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist Erik Acharius (1757–1819). With the development of the science of classification, the number of known lichen species grew from 150 to more than one thousand.

Figure 1a Foliose Lichens Figure 1b Usneas

Plates in Johann Jacob Dillenius, Historia Muscorum, 1741.

But it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that the use of increasingly sophisticated microscopes revolutionized the sciences (this was the age of vaccines) – and the representation of lichens. They allowed for better identification of them and completely removed all ambiguity by showing their symbiotic nature. Lichens are a combination of two organisms, a fungus and an alga. The German botanist Anton de Bary was one of the first to make that discovery in the 1860s.

In our time, it is molecular biology and computer technology that is revolutionizing lichenology, with the discovery of a third partner and the reclassification of lichen within the fungal kingdom: the realm of fungi, mushrooms that also have taken a long time to be defined and classified (half-animal, half-vegetable, they have had their own kingdom only since the 1960s). Phylogenetic research has resulted in more precise classification of species based on the evolution of phenotypes rather than the appearance of thalli: toward the ever more minute.

*

Lichens are neither secretions nor parasites. Gradually, science has shown that the stones, soil, and trees upon which they grow are only supports for affixation; lichens draw no nutritive matter from them.

*