Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Classic Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

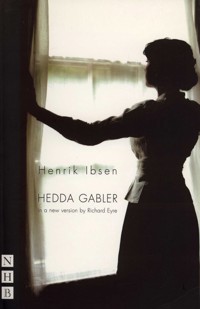

Ibsen's forensic examination of a marriage as it falls apart, in a version by Richard Eyre. How is a life well-lived? Alfred Allmers comes home to his wife Rita and makes a decision. Casting aside his writing, he dedicates himself to raising his son. But one event is about to change his life forever. Little Eyolf was first performed in 1894. This new version, adapted and directed by Richard Eyre, premiered at the Almeida Theatre, London, in 2015. The third in a trilogy of revelatory Ibsens, Little Eyolf follows Richard Eyre's multi-award-winning adaptations of Ghosts (Almeida, West End and BAM, New York), and Hedda Gabler (Almeida and West End).

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 86

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Henrik Ibsen

LITTLE EYOLF

in a new version by

Richard Eyre

from a literal translation by Karin and Anne Bamborough

with an Introduction by Richard Eyre

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Original Production

Epigraph

Characters

Little Eyolf

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Introduction

Richard Eyre

If I said that to watch Little Eyolf is a terrifying experience you might think I was being histrionic, and if I said that to experience that terror is enlightening, you might think I was being pretentious. But you’d be wrong: as with Greek tragedy, you’d be seeing the white bones of human experience. You’d be looking in the face of truth, which is always a journey into light, however painful.

Imagine that your only child has drowned and the child’s body is still missing. Incredulity will give way to numbness, numbness to anger, anger to despair, despair to exhaustion, exhaustion, perhaps, to acceptance, and acceptance, possibly, to hope. Add heartbreak to this – a metaphor that seems fanciful until it becomes undeniably literal – and then imagine that you and your partner don’t know how to comfort each other, barely know each other, don’t love each other, don’t want to be with each other. That’s the fate of the grieving, unloving, couple in Little Eyolf for whom there is no solace but each other. Tennyson’s line from In Memoriam could serve as their epitaph: ‘On the bald streets breaks the blank day’.

Grief is the anvil on which the issues – marriage, sex, class, fear of failure, fear of death, fear of life – are hammered out in Ibsen’s short play. It’s not, however, the sum of issues or subjects or themes, still less is it a moral primer. There are obvious poetic tropes – the rats, the deep waters of the fjord, the tops of the high mountains – but the characters are undeniably rooted in a physical world and exist entirely independently of their maker. None are constructs or symbols, not even the outlandish woman who comes to the Allmers’ house offering to take care of things that ‘bite and gnaw’.

As the young James Joyce said, ‘Ibsen’s plays contain men and women as we meet them in real life, not as we apprehend them in the world of faery.’ And, as a small child in rural Dorset in the 1950s, I did meet them – the man with skin like beech bark, thick black stubble and large black eyes whose language I couldn’t understand: an Italian prisoner of war looking for work; the small woman with a weasel face swathed in coloured scarves: a Gypsy selling clothes pegs. They were frightening to me, threats to the inviolability of my safe, middle-class territory.

Above all, Little Eyolf asks questions about marriage: how can survive it without sex, without mutual respect and without children? It was written by a sixty-six-year-old man whose thirty-six-year-old marriage had been a source of quiet unhappiness to him, and almost certainly more so to his partner. He’d returned from twenty-seven years – more than half his married life – in self-imposed exile in Italy and Germany to discover that he was revered in Kristianiana (known now as Oslo). He became a popular, if reclusive and curmudgeonly, public figure and with a remorseless lack of self-pity began to audit his life in his writing. In The Master Builder, which preceded Little Eyolf, and in John Gabriel Borkman, which succeeded it, he wrote of the personal landscape that he described as ‘the contradiction between ability and aspiration, between will and possibility’ – the conflict between love and work, between selflessness and selfishness, between comradeship and isolation, between the brightness of passion and the bleakness of unrealised emotions.

Ibsen might have said, as Chekhov did, that, ‘If you are afraid of loneliness, don’t get married.’ Although the two writers –almost exact contemporaries – have much in common, I used to think that a liking for them both was impossible: you declared yourself for one party or the other. But the more familiar I’ve become with Ibsen’s plays, the more I’ve come to think that Chekhov was speaking for both of them when he said:

It’s about time for writers – particularly those who are genuine artists – to recognise that in this world you cannot figure out everything. Just have a writer who the crowds trust to be courageous enough and declare that he does not understand everything, and that alone will represent a major contribution to the way people think, a long leap forward.

Both writers were prescient about attitudes to class and to sex. The finely calibrated class distinctions in Little Eyolf are thoroughly recognisable in the social topography of today and you don’t have to look further than the refugee detention camps at Calais to find parallels with Ibsen’s feral boys on the beach and the rat-woman on the doorstep. The treatment of sex seems hardly less contemporary. It isn’t buried in Freudian allegories, it’s all too present in Rita’s rebuke of Alfred for spurning her and in his desire for his sister, Asta. A ménage à trois is even suggested as a resolution of the sexual triangle. The absence of sex between husband and wife engenders hatred; its presence between brother and sister poisons love.

Little Eyolf is the godparent of many plays about marriage – Strindberg’s Dance of Death (written six years after Eyolf), O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Whitehead’s Alpha Beta, as well as countless TV dramas, the most recent being Doctor Foster and The Affair. It continues to exist as a play for today in much the same way as little Eyolf continues to exist for his parents. The appalling irony for them is that they recognise his humanity in death where they had ignored it in life. What remains of their son is hope – merely a glimmer of it – the hope that they will start to acknowledge their shared humanity with the dispossessed, and that their stoicism will soften into something like love.

This is the third Ibsen play that I’ve adapted for the Almeida Theatre. The other two, Hedda Gabler and Ghosts, were no less intense and testing than Little Eyolf. As with the other two plays I worked from a literal version – this time by Anne and Karen Bamborough – and had the original (Dano-Norwegian) text by my side. I was always curious about the length and sound of the original lines even if their sense was only accessible with a dictionary.

The only existing translation I looked at was an American version published in 1909, introduced and translated by the journalist and critic H. L. Menken, the great aphorist and satirist. ‘It is mutual trust,’ he said, ‘even more than mutual interest that holds human associations together. Our friends seldom profit us but they make us feel safe. Marriage is a scheme to accomplish exactly that same end.’ In his introduction to the play, he says this:

Ibsen set himself to study the influence of marriage upon human character and happiness. The things which differentiate marriage from all other forms of contract, he saw clearly enough, are its unconditionality and its unlimited duration. But does a man ever attain such complete mastery of himself as this unconditional promise implies? Is he really superior, after all, to the forces which make for evolution – the forces from which Allmers deduces his ‘law of change’?

I’ve tried to animate the language in a way that felt as true as possible to what I understood to be the author’s intentions, but even literal translations make choices and the choices we make are made according to taste, to the times we live in and how we view the world. All choices are choices of intention, of meaning. I’ve made a few small cuts and have replaced the three locations of the original – a ‘richly furnished garden room’, a ‘small valley in the forest’, and an ‘overgrown rise in the garden’ – with a single location: a veranda looking out over the fjord. What I have written is a ‘version’ or ‘adaptation’ or ‘interpretation’ of Ibsen’s play, but I hope that it comes close to squaring the circle of being close to what Ibsen intended while seeming spontaneous to an audience of today.

This version of Little Eyolf was first performed at the Almeida Theatre, London, on 26 November 2015 (previews from 19 November), with the following cast:

ALFRED ALLMERS

Jolyon Coy

BJARNE BORGHEIM

Sam Hazeldine

RITA ALLMERS

Lydia Leonard

ASTA ALLMERS

Eve Ponsonby

WOMAN

Eileen Walsh

EYOLF

Adam Greaves-Neal

Tom Hibberd

Billy Marlow

Director

Richard Eyre

Designer

Tim Hatley

Lighting Designer

Peter Mumford

Sound Designer

John Leonard

Projection Designer

Jon Driscoll

Casting Director

Cara Beckinsale

Assistant Director

Sara Joyce

Company Stage Manager

Laura Draper

‘On the bald streets breaks the blank day’

Tennyson: In Memoriam

Characters

ALFRED ALLMERS, writer, thirty-six

RITA ALLMERS, his wife, thirty

EYOLF, their son, nine

ASTA ALLMERS, Alfred’s half-sister, twenty-five

BJARNE BORGHEIM, civil engineer, thirty

WOMAN, rat-catcher, forty-five

This ebook was created before the end of rehearsals and so may differ slightly from the play as performed.

Early-morning mist. Through the mist we see the sun start slowly to burn through.

The sun merges into water – the surface of a fjord. The calm surface dissolves into a whirlpool.

The image of water dissolves into the view of a narrow fjord banked by wooded hillsides.

It’s morning in early summer. The sun shines warmly on an elegant veranda – a deck without railings. It’s a wealthy house: varnished wood and Norwegian red. On one side there’s a round outdoor table flanked by two chairs; on the other side there’s a sort of chaise longue/sunbed with rich cushions and rugs. By the chaise there’s a small coffee table. There are steps which go down, out of view, from the veranda towards the fjord. There’s a door to the house on one side, open French windows.