18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

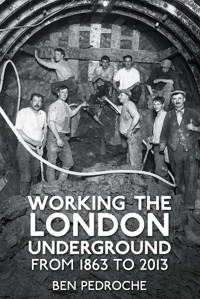

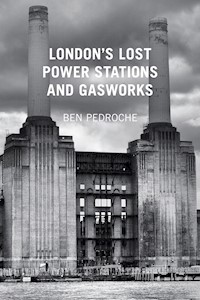

Many of London's original power stations have either been demolished, converted for other use, or stand derelict awaiting redevelopment that is seemingly always just out of reach. However, in their prime these mighty 'cathedrals of power' played a vital role in London's journey towards becoming the world's most important city. Gasworks also played a key role, built in the Victorian era to manufacture gas for industry and the people, before later falling out of favour once natural gas was discovered in the North Sea. London's Lost Power Stations and Gasworks looks at the history of these great places. Famous sites that are still standing today, such as those at Battersea and Bankside (now the Tate Modern gallery), are covered in detail, but so are the previously untold stories of long-demolished and forgotten sites. Appealing to anyone with even the slightest interest in London, derelict buildings or urban exploring, this book uses London's power supply as the starting point for a fascinating hidden history of Britain's capital, and of the more general development of cities from the era of industrialisation to the present day.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 A New Thirst for Energy

2 Birth of the Industry & the Major Players

3 The Great Cathedrals of Power

4 Bringing Gas to the People

5 Harnessing the Mighty Thames

6 Closure, Abandonment & Dereliction

7 Redevelopment & New Uses

8 A Dirty Legacy for a Cleaner Future

References & Further Reading

Plates

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to my wonderful wife Louise Pedroche for the never-ending love, enthusiasm and support for the writing of this book. Your patience and understanding during the long nights of writing and hectic research trips are very much appreciated. Thanks also for taking so many of the amazing photos included. Thanks to all my family and friends, and the various people and organisations who have allowed me to use archived images, especially Paul Talling, the London Transport Museum, the Museum of London, the Science Museum, the Greenwich Heritage Centre, The Enfield Society, Helmut Zozmann, Neil Clifton and many others. I owe a great debt to the authors of several books and websites included in the bibliography section. Their detailed work helped me research a subject that isn’t widely covered. Lastly, thank you to everyone at The History Press for being there every step of the way.

INTRODUCTION

London is a city in a constant state of change. Always moving, always evolving, the same as it has done for centuries. It is a place at the forefront of everything ultra-modern, but it is also defined by its glorious past. Its rich history has been preserved in hundreds of buildings across the city, in particular its landmarks associated with religion, royalty, government and war. An area often overlooked by history is London’s industrial past, and it is only in recent decades that great effort has been made towards the preservation of buildings that often used to dominate whole districts, and provide work for thousands of men.

The impact of London’s docks and railway network are two subjects that, quite rightly, have commanded the respect of historians and the interest of many others. There are other industries, however, that seem largely forgotten, despite their legacy and the influence they have had on shaping modern London. Two of these areas in particular are London’s gas manufacturing industry, and its electrical power generation industry.

Perhaps one of the reasons is that former industries like these lack much of the romance and nostalgia of others. The image of London as the world’s most important port is one that’s been captured many times in literature and on film. Similarly, the golden age of the railways evokes sentimental memories of a time often naively perceived to have been more simple and easy.

In reality, life in nineteenth-century London was far from simple, with millions living in poverty. Men, women and children were forced to work and live close to the so-called ‘stink industries’ that dominated large parts of the growing metropolis. Among the worst contributors to a poor quality of life were mills, chemical works, factories and, of course, gasworks and early power stations.

The dirty legacy of such places is probably the reason why they are often only briefly mentioned in the timeline of London’s story. The manufacture of gas was a hot and hazardous job, particularly in the early years of the industry. Electric power stations were also places undesirable to most. Both relied heavily on the burning of coal in order to create the energy they needed, and therefore filled the London sky with pollutants at a time when the concept of a carbon footprint would have been difficult to explain.

Yet this was simply Victorian London at the height of its industrial heyday, where dirty and dangerous jobs were just part of normal life for thousands of workers. Every great engineering feat of the Victorian era involved men having to work in wretched and sometimes deadly conditions, from Marc and Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Thames Tunnel, to Joseph Bazalgette’s sewer system and the first underground railways.

With pioneering works such as these, however, the historical focus is almost entirely on the achievements themselves, and the visionary men that created them. But to dismiss gasworks and power stations each as nothing more than simply one of many industries that came of age in the nineteenth century would be a disservice to the great innovators who built them, and the workforce that brought them to life.

Gas production quite literally enabled London to become a brighter and better developed place. As the nineteenth century drew to a close and the next one started, gas began to be superseded by electricity. This in turn gave Londoners power direct to their homes, helping the city’s continued growth as the centre of the empire.

Just as with the railways and shipping companies, the firms that ran the gas manufacture and electrical supply boasted long and eloquent names that befit their importance. The men who created them and served as chairmen and directors were well-turned-out gentlemen, among some of the sharpest minds in the City of London and beyond.

The most impressive thing about power stations and gasworks was usually the buildings that housed them. For gasworks, it was the huge gasholders and their frames that stood out for miles. It is only when seen from close up that their fine craftsmanship and often highly decorative features are revealed. For power stations, it was mega-sized brick structures and their chimneys that proved most awe-inspiring, especially those that once lined the banks of the Thames.

Much has fortunately been preserved for all to see, with many sites given a second life under a different purpose. The former power station at Bankside is now home to one of the world’s most successful art galleries, and Battersea Power Station is a building familiar to all Londoners and many from further afield. Elsewhere across the city, huge gasholder frames still stand proud, and indeed many are still used in some capacity by today’s modern gas supply companies.

Other buildings and structures still stand but their former uses have long been forgotten, like at the minimalist bar in Shoreditch that once housed electricity generators, or the rotting wooden pier supports in the Thames at Deptford that once delivered coal to one of the biggest power stations in the world. Many more buildings have simply disappeared without a trace, with nothing left behind to suggest they ever even existed.

London’s Lost Power Stations and Gasworks is a collection of the finest and most important examples of each, regardless of whether they still exist today or not. It is a journey through the story behind each building and the companies that built them. It is also an exploration of the historical context of London of which they were a part, and the legacy they have left us with today.

The buildings and structures covered in the pages that follow played a vital role in the development of London as the greatest city of the world. Therefore they deserve their place in the history of London just as much as other revered structures and monuments.

The sheer size of London’s disused power stations has been a source of fascination for the author for a number of years. Similarly captivating are the gritty and urban aesthetics that abandoned buildings and gasholders create.

It is an interest that began in wonder at the imposing telescopic gasholders often passed as a young boy in the author’s city of birth, Nottingham. It is a passion that has continued to grow since moving to London, and part of a wider interest in the city’s lost industries.

1

A NEW THIRST FOR ENERGY

London’s need for power was the result of several major developments in the 1800s and early part of the twentieth century. It was perhaps the most important period in the city’s long history; a time during which London grew in size and stature to become the most vital city on earth, before later being ravaged by the effects of two catastrophic world wars, only to emerge strong as always.

GAS POWER FOR LIGHTING

Gas production was introduced to London in the first two decades of the nineteenth century, and progressed during the beginning of the reign of Queen Victoria. It was an era defined by advancements in technology and science, changes in government both home and abroad, and by the fruits of the Industrial Revolution.

The British Empire grew ever bigger, with each new territory opening up greater trade routes to the rest of the world. The Port of London quickly developed into the largest collection of docks, wharves and riverside factories the world had ever seen, built to handle the huge selection of goods flowing in and out of the city. The success of the docks led to thousands of new buildings being constructed, with many villages and towns becoming absorbed into the capital as its sprawl rapidly increased outwards from the original medieval City of London. The industry that grew in and around the docks provided work for hundreds of thousands of men across London, particularly those from the East End. Many would later lose their jobs in the second half of the century as the docks began to suffer from the first signs of the major decline that would come in the decades that followed.

By the mid–1800s, London was again leading the way at the cutting edge of another major new innovation, this time on dry land. The coming of the railways had a huge impact on the city, with miles of new lines constructed that helped to connect the growing metropolis with the rest of Great Britain. All of London’s most famous railway stations were built in this period, allowing for millions of people to flow in and out of the city every year.

In the early 1860s the streets of London had become such a congested mess that a new system for how people moved around the city was desperately needed. The only solution was to go underground, and it was at this time when the first lines on what would later be called the Tube were opened.

Other industries also developed across the city, including clothing manufacture, flour mills and hundreds of factories. Conditions were often appalling, with thousands of men and women forced to work in factory jobs that in many cases were comparable to slave labour.

Occurring in tandem with the establishment of London’s new industries was the other major social change that defined the Victorian era; a dramatic rise in population that would see millions of new arrivals to London. The growth of industry had created new jobs for London’s workforce. But the coming of the railways also made it easier than ever before for those from other parts of the surrounding counties to move to the city in order to find work. An increasing number of people also began to arrive from all over the world. Each new group of immigrants began to settle in the capital and establish their own communities, starting their own types of industry in the process. The Irish and the Jewish accounted for much of the influx of new arrivals, followed closely behind by those from Bangladesh, India and several other nations.

Other factors that contributed to the population increase included vast improvements to healthcare and medical treatment. A rise in the number of marriages led to more women giving birth, and the medical advancements helped to ensure that more babies survived their birth and early years. At the other end of the life cycle, Londoners were also beginning to live longer. This was partly the result of the better healthcare standards, but also because of the fact that the nineteenth century was a time of relative peace, with no major war on home soil, and no widespread disease outbreak.

The resulting population increase brought millions of new residents to the streets of London. The more people that arrived, the more power was needed to accommodate them. The earliest gasworks, however, produced gas primarily for commercial use only. They were used to supply gas lighting for factories and a range of other different workhouses, replacing the oil lamps of a previous generation.

Class distinction in nineteenth-century London was clear cut, with no middle ground. You were either rich, or you were poor, and most were the latter. Low income rates and the rapid increase in population meant that millions lived in poverty, squeezed into cramped housing along narrow streets. The East End in particular was infamous for its slums and the depravity that such places tended to breed.

Gas lighting for private, residential use was therefore reserved solely for the wealthy during much of the century. Nevertheless, demand did later grow for public street lighting. Its provision by several local authorities across the city helped to lower crime rates, and allowed Londoners to do more in the evening.

By the latter part of the century gas was being manufactured on a massive scale by gasworks across London. The lower prices that mass production offered meant that gas could finally become a realistic commodity for every social class, bringing it directly into people’s homes for use by gas lights and for cooking.

ELECTRICITY FOR THE MASSES

The Victorian era may have been the age of gas, but the twentieth century was dominated by a new form of power. As the new century began, advances in technology and engineering allowed for electricity to emerge as a new way of powering London. Similar to gas, it was first used only for commercial purposes, or in select homes owned by the wealthy.

Shops, restaurants and theatres are just a few examples of businesses that benefited from the foresight of their owners to install electrical lighting. The extra custom it created made such businesses the envy of other traders, and it wasn’t long before there was huge demand for electrical power throughout London.

What followed soon after was a desire felt by everyday people to have electricity piped directly into their homes, first for lighting, and various other appliances in later years. A mixture of private and council-owned power stations were built to meet the expected demand, although it was in fact largely the electrical companies themselves that created the demand in the first place.

Electrical power generation on a massive scale was pioneered in London. Power could now be supplied across long distances and to millions of consumers at once. It was an innovation widely promoted by each electricity company, encouraging people in the city to want it in their homes and places of work.

In the context of today’s society, it is difficult to fathom the concept of electricity being anything other than a basic public service that is always there when we need it. But in its early development it was sold as a product, creating a market that grew in much the same way as the popularity of mobile phones, the internet and other global communications did in the century that followed. It was new, it was sold as a must-have commodity, and everyone ended up wanting it.

The rise of electricity did of course have a detrimental effect on gas manufacture. Electric lighting made the gas lights of old seem archaic in comparison, and it led to serious decline for many gas companies. London’s gasworks still produced a product that was in demand for cooking and heating, although this would begin to disappear by the 1960s.

POWER FOR TRANSPORT

Another increase in demand for electricity came from the continued success of London’s transport system. In the late nineteenth century and early part of the twentieth, electric trains rapidly replaced steam on the Underground network. More and more people were using the Tube every day, resulting in a higher frequency of trains per hour being needed. This called for high amounts of electric power, and with no National Grid at this stage, it was left to the responsibility of the railway companies to generate electricity themselves.

The initial solution was a number of small power stations owned by individual lines, but as passenger numbers increased and companies amalgamated into one network, it was clear that a more suitable long-term plan was required. The outcome was a series of large power stations constructed specifically to power the network, with extra capacity left over to supply new lines like the Victoria and Jubilee that would arrive later. Elsewhere, the city’s tram network also needed powering in the early decades of the twentieth century. This was managed in much the same way as the Underground, with tramway operators having their own small generating plants, before later being powered by the dedicated large power stations. London’s main-line railways also later made the switch from steam to electric traction, which again demanded power from a series of purpose-built power stations across the city.

The success of the Underground network was itself a by-product of London’s continued growth during the last century, both in population and physical size. The first half of the twentieth century was characterised by the devastating impact of two world wars. Yet population continued to rise regardless, especially in the period between wars, when London spread out in every direction, causing its number of residents to swell to more than eight million.

The mass of people, and the products and services they demanded, meant that London was able to avoid being impacted too greatly by the global economic downturn of the 1930s. Rather than suffer decline, many industries continued to grow, among them the electricity supply companies.

By the 1940s, the landscape of London was dominated by large power stations. The British Empire had perhaps lost much of its power, and other cities around the world may have taken away some of London’s status as the centre of the world, but it was still a city on the rise. As technology, youth culture, arts and entertainment, tourism and commerce all continued to grow, so did the need for electrical power. It is a demand that has never eased since. Today, London still requires huge amounts of gas and electricity. Gasworks have been replaced by supply from the North Sea and beyond. The major power stations have all but gone, replaced by more efficient and environmentally friendly plants. But it is still a city hungry for power, a necessity not likely to ever disappear.

2

BIRTH OF THE INDUSTRY & THE MAJOR PLAYERS

With London’s ever-growing need for power in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it didn’t take long for the wheels of commerce to start turning in unison with the mechanical and industrial developments they began. Demand was high, and it was a demand that needed to be met. Although London’s electricity supply, gas manufacture and other such power-related industries developed at different times and in different ways, the principle was always the same. Scores of different companies started to appear almost overnight, creating fierce competition within each sector, and often mass confusion for the early consumers.

As is usually the case in business, however, many firms disappeared just as quickly as they appeared, allowing a small group of large companies to take control, absorbing everything in their path towards the top. The birth of the gas industry in particular is a tale littered with faded memories of lost companies that were forced to amalgamate with a handful of major businesses. Other companies managed to dominate their industry from the very start, having become established so early that no one else ever really stood a chance of competing against them.

This chapter explores how each power industry emerged, and the major players within them. Many of the power stations, gasworks and other buildings discussed in this chapter still exist, and will be explored in full detail in later sections of the book. Further information about how each power system actually works will also be covered later.

GAS PRODUCTION ARRIVES IN LONDON

Electricity rapidly earned its place as the leading power industry in the latter part of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. But before that there was gas manufacture, a genuine stink industry that came of age in Victorian London.

Its primary use in the 1800s was to provide lighting, specifically by powering gas lights. Although not capable of achieving the same brightness as the electrical lights that would later replace them, gas lights were a vast improvement on the candles and oil lamps that came before them. Instances exist of gas being recommended as a way of powering lights as far back as in the 1680s, suggesting that the basic principle was far from new. But it was only in the early part of the nineteenth century that sufficient advances in chemistry meant that what was once merely theoretical could now become a reality.

There was little demand for public gas supply at first. The early companies that began to operate instead focused their attention on providing lighting for factories and mills. The appeal was simple: gas lights were cheaper, and more powerful and efficient than oil lamps or candles. The lack of a naked flame also provided a safer environment, especially for those factories manufacturing flammable products.

Taking note of how water was already being supplied directly to buildings and houses by way of mains built below streets, the potential for gas to be delivered to consumers in the same way was soon realised. It wasn’t long before the focus of attention shifted therefore from industry to the public domain.

Although London was often surprisingly lacking compared to other parts of Britain when it came to capitalising on new industrial advancements, it was in fact at the centre of the early gas industry. And so it was in London, in Westminster to be exact, where the world’s first public gas supply company was established in 1812 by royal charter. It was called the Gas Light & Coke Company and, quite remarkably, managed to retain its position as the biggest gas producing firm in London until it was nationalised more than 130 years later.

The company owes much of its success and ambition to German inventor Frederick Albert Winsor. Something of a fantasist and unabashed self- promoter, Winsor came to London in 1803 to generate interest in his pioneering work relating to gas lights and their potential for public lighting. Yet even at this point in time, at the very beginning of the century, the concept was not entirely new. It was an idea already being developed in Paris, but also closer to home in Birmingham.

The advancements in the West Midlands were thanks to Scottish engineer William Murdoch. Building on the knowledge gained from reports of wealthy businessmen who had used gas to light their homes, it was Murdoch who recognised the potential for gas lighting to be used in factories. Murdoch was employed at the time by Boulton & Watt, a company whose steam engines had played a significant role in the Industrial Revolution. As a firm already renowned for its innovation, the chance to be part of a new scientific breakthrough made it easy for Murdoch to gain permission to experiment with lighting at their factory in Birmingham.

The experiments proved successful, and by 1803 gas lighting at the factory became a permanent fixture. This was followed by similar installations at various other factories. Murdoch was doomed to become merely a footnote in the history of gas supply, however, thanks to his short-sighted insistence that gas lights would only ever be suitable for industry.

Winsor on the other hand did see its public supply potential, and set about proving it with a series of early lectures and demonstrations, most of which failed to impress potential investors for his proposed National Heat and Light Company. It was a PR campaign that Winsor had already failed at in Paris, but his enthusiasm and persistence eventually started to pay off in London.

The huge potential of Winsor’s idea for using mains to supply gas to the public could no longer be ignored. By 1807 a consortium of investors began a series of moves towards shaping his ideas into a serious business model. The first task was to gather support in Parliament, an exercise that was met almost immediately with opposition. Although the consortium claimed that the new proposed company – now set to be called the New Patriotic Imperial and National Light and Heat Company – was being founded on the notion that it would provide a much-needed public service, the detractors were quick to point out that a lack of competition would lead to a monopoly. One individual figure opposing the new company was Murdoch, a man perhaps more than a little bitter that his early innovation was now on the verge of major financial success without his involvement.

Whatever the motives of those opposing Winsor, the various objections raised were enough to ensure that the company didn’t obtain its charter. Other unsuccessful attempts followed, but the consortium did finally succeed in gaining their royal charter in 1812. Now to be known as the Gas Light & Coke Company, the original plan for a national gas supply had been downsized to London only, but it was still enough to lay claim to being the first company of its type the world had ever seen.

Plaque commemorating Frederick Winsor’s early gas demonstrations.

The Gas Light & Coke Company’s first gasworks in Westminster.

The company opened its head office and first gasworks on what is now Great Peter Street in Westminster. Keen to widen their reach as quickly as possible, the Gas Light later opened two further gasworks in Shoreditch, notorious in the nineteenth century as being one of the most crime-infested areas of London. The first was located on Curtain Road, while the second was on Brick Lane, built on the site of an old brewery. Neither proved to be of much use, primarily because each was located too far from either a canal or a river. A gasworks needed a constant supply of coal, and the most cost-effective method of delivering this was via barge. The lack of waterways alongside either of the Shoreditch works meant that instead the company had to pay the higher costs involved in using trucks to deliver its coal supply.

The rising demand for gas lights also meant that the two early works soon became inadequate, having little room for expansion. It wasn’t until much later in the century that the company built a new and improved works. For now though, the Gas Light was firmly established as the dominant force in a new but rapidly growing industry, and within a few years it began to run at a significant profit.

Frederick Winsor was kept as an employee, and served as the public face of the company during its fight to obtain its charter. It was ultimately his lack of business acumen that led to him playing only a minor role in the Gas Light’s long-term success. He later fought to be recognised officially as the creator of the company, and therefore be compensated accordingly with a share of its profits. His demands were unsuccessful, with the company going to great lengths to make it clear that their operation was different enough to Winsor’s original concept for him to make any serious claim. Winsor later returned to France to try to set up a similar business in Paris, but this only led to further failure. He died soon after in 1830.

Today, Winsor is still remembered as the company’s founder, and there is a monument dedicated to him in the grounds of Kensal Green Cemetery. In addition, a road close to the Gas Light’s largest works was also named after him.

The success of the Gas Light & Coke Company from 1812 onwards led to a rush of other companies entering the market, and by the mid–1830s London had hundreds of public gas mains in operation. Unsurprisingly, competition between rival companies was fierce. It draws comparison with the gas and electricity supply industry of today, where consumers are constantly being encouraged to switch to a different provider.

But while today the methods by which competitors attempt to outdo each other usually involve nothing more sinister than undercutting prices, the tactics used in the nineteenth century were far more dirty and underhand. It was not uncommon for workers to be sent out to sabotage the gas mains laid by rival companies, and even steal their main’s connections. Early consumers may have been able to reap the benefits of such actions, but they had a negative impact on gas company employees. If working in one of London’s stink industries wasn’t already hard enough, wage reductions and increased danger must have added significantly to the low morale and poor working conditions. Overheads, wage bills and safety-related maintenance were all costly activities for a company willing to cut corners in order to offset profit reductions caused by having to lower their prices to beat competitors.

It was clear that change was necessary, not only to improve the inner workings of the industry itself, but also to try and balance the success of the Gas Light with a genuine rival. It was still the most powerful company in the gas industry, regardless of how many smaller firms were out to take the throne.

It was a situation that played directly into the hands of the early detractors and their fears about a monopoly, but there was also now a second wave of men protesting at the way the industry was progressing. One of them was a Stepney businessman named Charles Hunt, who in 1837 spearheaded the creation of the Commercial Gas Light & Coke Company. It was an ambitious new firm that would give the original Gas Light & Coke Company some real competition. Hunt’s manifesto was to build a company that would be owned and run by consumers, supplying a better and cheaper service than its competitors. Various local businessmen were encouraged to invest and purchase shares, and by 1839 the company had secured enough financial backing to open its own gasworks at Stepney.

The Commercial Company’s strategy was to focus its attention on large areas of east London not already controlled by the Gas Light, including parts of Wapping, Poplar, Limehouse and Shadwell. Several of these were, however, districts already being supplied by smaller companies, most of which helped to ensure that the Commercial Company was given a harsh reception. In a return to the same skulduggery that was rife in the early days of the gas industry a decade before, these local companies took to digging up expensive new mains built by the Commercial Company, in particular in Mile End.

The fear was that a large company like this would take all of their business. It was in fact a reasonable fear to have, and one being felt perhaps most by the Gas Light. They could now see a serious contender on the horizon for the first time in their history.

The growing resentment towards the Commercial Company was further exacerbated when the firm achieved great financial success under the leadership of the new chairman, Charles Salisbury Butler. His foresight in convincing the board that the company should expand its reach to Whitechapel, Spitalfields and Bethnal Green proved to be a positive move, and enabled the firm to weather its early financial struggles.

The initial reaction from the Gas Light, and indeed various other small companies who at first had set out to ruin the Commercial Company, was to propose ways for each company to work together. The reasoning was simple: ‘You stay away from our territory, we’ll stay away from yours, and they’ll be enough consumers for everyone to make a profit.’ The Commercial Company’s response was to refuse any such alliances, no doubt acutely aware of the sense of desperation pervading the actions of their rivals.

There were, however, many occasions when the various competing gas companies did unite in order to protect their shared interests. Strike action by gas workers was a frequent issue, and rival firms would often lend their own workforce to fill the void left by the men on strike elsewhere. Strikes, such as those that took hold at gasworks and other industrial workplaces in the 1860s and ‘70s, could often turn violent, with workers sometimes facing criminal charges. This meant that when workers were sent to help out at other works, the official line was that they were there simply to fulfil regular duties. But off the record, they were often there as extra muscle.

It would have been hard to deny this sinister pretence as the real reason for rival workers being deployed on one particular night in August 1850. It is a date that marks the darkest hour in the history of the Commercial Company and the nineteenth-century gas industry as a whole, and was given the nickname the Battle of Bow Bridge.

A new gas company known as the Great Central Gas Consumers Company had arrived on the scene in 1847 with a view to becoming a serious threat to the dominance of both the Gas Light and Commercial Company. Reminiscent of the founding principles under which the Commercial Company itself was created – many of which had long since been eroded – the Great Central aimed to build a company that would provide gas at a lower and fairer price, whilst still ensuring a healthy return on investment for its shareholders. Of particular frustration for the Commercial Company was the fact that their new rival decided to open a new gasworks at Bow Common, right in the heart of Commercial Company territory.

Similar to the days of sabotage that the Commercial Company had itself suffered in the early years, they deployed a team of ‘workers’ from their own gasworks and those of the Gas Light one evening in early August to disrupt workers from the Great Central as they tried to construct a new mains pipe across Bow Bridge. They succeeded in driving away the workmen, and proceeded to construct their own mains pipe across the same bridge. It was a main the Commercial Company did not need, and was instead built entirely for the purpose of ensuring their rival would have no room left on the bridge for a main of their own. The men then went a step further by creating a barrier across the bridge.

What they didn’t account for was the size of the Great Central’s defences, and within hours a 300-strong army of men arrived to overpower the Commercial Company’s workers. They stormed the barricade, destroyed the new main and replaced it with their own. By the following day there were several men injured from fighting, and others arrested and remanded in custody for violent behaviour.

The overall success of the Commercial Company had a profound effect on the industry. But in reality the Gas Light remained as the market leader, and steadily increased its power by amalgamating with many of its smaller rivals. Every existing company it acquired gave the Gas Light not only increased market share but also more and more gasworks. By 1930 the company was supplying gas to huge parts of London and its surrounding districts. More than thirty different companies were absorbed by the firm between 1812–1932, giving them coverage that ran as far as Staines, Brentford, Southend-on-Sea and Barking.

The Commercial Company followed suit with a series of amalgamations of its own, including the strategic purchase of the British Company. The purchased company had previously spent significant time and resources years earlier on trying to ruin the business of their now owners.

The landscape of the industry changed again in 1868 when new legislation was passed which meant fines could be charged to companies who failed to supply gas of a high enough quality to power gas lamps to their full capacity. The result was that several companies had to modernise their existing gasworks so that they could meet the required levels of capacity, or simply build new, larger works instead.

The latter option proved to be the most viable long-term solution for the major companies, and it sparked a new era of mega-sized gasworks that soon became a common feature across London. The Commercial Company expanded its works at Stepney, and the Gas Light opened a new site in East Ham. Known as Beckton Gasworks, it was one of the world’s biggest industrial sites on its opening in 1870.

Another company to open a huge gasworks in the 1870s was the Imperial Gas Light & Coke Company, who began construction of a new works at Bromley-by-Bow, complete with no fewer than seven gasometers.

The Imperial was in fact a significant player in its own right. It was founded in 1821 and soon began to gain control of significant parts of north, east and west London, with considerable works at Shoreditch, Kings Cross, Fulham and the new site at Bromley-by-Bow. A key figure in its success was Consultant Engineer Samuel Clegg, who had long been associated with the gas industry. His credentials included assisting William Murdoch with his early gas light experiments at the Boulton & Watt factory. He also acted as engineer to the Gas Light during its early years. This connection with the largest company of all would come full circle in 1876 when the Imperial became one of the many companies absorbed by the Gas Light. It was a major factor in the continued dominance of the company, giving them almost total coverage of central London and its vicinity.

The South Metropolitan Gas Company was another thriving business that built a large gasworks in the latter part of the century. It was a company in good health by 1879, boosted by recent amalgamations with the Phoenix Company and the Surrey Gas Consumers Company, two firms with lucrative coverage of London districts south of the Thames. Their major new works opened at East Greenwich in 1886, on the site of what is now the O2 Arena. It would prove to be the last great gasworks constructed in London. The South Metropolitan continued its success into the next decade, and would later come close to purchasing the Gas Light. The deal never materialised, but the South Metropolitan did later become a major shareholder in the Commercial Company. The Gas Light had itself made several offers to amalgamate with the Commercial Company between 1873 and 1883, but was rejected each time.

By the turn of the century the gas industry was being hit hard by the growing success of electrical power, with further decline taking effect after the discovery of natural gas in the North Sea. Chapter 6 will discuss the decline of the industry and its major gasworks in further detail.

ELECTRICITY TAKES OVER

In the twenty-first century, when our entire lives revolve around technology, it is hard to imagine not having electricity when we want it. But in the latter part of the nineteenth century there were no appliances, and the electricity supply industry existed almost solely for the purpose of supplying lighting to those who demanded it.

Although this demand would later grow and indeed be met on a huge scale between the 1880s until the 1940s – with mega-sized power stations being built across London – the city’s power industry actually began under far less spectacular circumstances. The story begins with an artist named Coutts Lindsay, who opened an art gallery on Bond Street in 1877. Named the Grosvenor Gallery, it was opened to showcase the work of new artists whose work was seen as too radical for the mainstream galleries.

When it was decided that electrical lighting should be added to the venue in 1883, the entrepreneurial Lindsay simply purchased the machinery needed to generate electricity himself. It didn’t take long for the owners of other businesses in the Bond Street area to also want electrical lighting, and so Lindsay obliged by expanding his basic set-up to supply various other firms with power at an affordable price, via overhead cables. Within two years the supply business was so successful that Lindsay expanded again with the opening of the Grosvenor Power Station, under his new company name of Sir Coutts Lindsay Co. Ltd.

This small but significant power station continued to provide a public power supply until 1887, widening its reach along the way. When a large new power station was opened at Deptford in the same year, the site at Bond Street was downgraded to a substation, which can still be seen today on Bloomfield Place, just off what is now New Bond Street.

Around the same time as the success of the Grosvenor Gallery, a similar operation was also gaining popularity in the theatre district. After inheriting the family business from their father, Swiss brothers John Maria and Rocco Joseph Stefano Gatti had built up a successful empire that included ownership of restaurants and theatres, including the famous Adelphi. Just as with Lindsay’s art gallery, the installation of a small generating station, built in order to power electric lighting, soon attracted the attention of other local businesses. The Gatti brothers founded the Charing Cross and Strand Electrical Supply Company to meet the demand, and were soon selling the use of its power source to large parts of London’s West End.

Also operating by 1883 was a small electricity supply close to Farringdon, in the City of London. It was built by the Edison Electrical Company, owned by famed American inventor Thomas Edison, especially to provide power for street lighting along the Holborn Viaduct. This decorative bridge across the former valley of the River Fleet had been opened with much fanfare by Queen Victoria herself. It was therefore a suitable London landmark on which to experiment with electrical street lights. Although short-lived, the generating equipment’s success in providing lighting not only to the viaduct but also several houses nearby meant that Edison’s building at 57 Holborn Viaduct had in effect become the world’s first public power station.